Abstract

Background

Feeding and eating disorders are major factors in nutrition problems. Mothers have a big role in shaping feeding and eating behaviors. This study aimed at estimating the prevalence of feeding and eating disorders among children in pediatric outpatient clinics (6–12 years old) and comparing personality factors among mothers of children with feeding and eating disorders versus those without feeding and eating disorders.

Results

This study included 528 children who were screened for feeding and eating disorders using the DSM-5. For the detected children, their mothers’ personalities were assessed using Cattell’s 16 personality factor test after history was taken using a child psychiatric sheet. The resulting prevalence of feeding and eating disorders is 13%, and the major mother’s personality factor that contributed is the control factor.

Conclusions

Certain personality factors of the studied mothers (controlled, tender-minded, imaginative, forthright, and apprehensive) correlate with the prevalence of feeding and eating disorders among their children, compared with those without feeding and eating disorders. Mothers’ personalities should be assessed in children with feeding and eating disorders, especially when these factors seem likely.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Feeding and eating disorders are characterized by a persistent alteration of eating or eating-related behavior that is associated with altered food consumption or absorption, resulting in impaired physical or psychosocial functioning. Diagnostic criteria according to DSM5 are provided for PICA, RD, AFRID, AN, BN, and BED [2]. About 25–45% of the pediatric population has a feeding or eating disorder during childhood [4]. These disorders are associated with many negative consequences, such as decreased weight gain [22], nutritional deficiencies and poor dietary variety [7], growth failure, cognitive and developmental delay [5], poor eating habits in adulthood [6], and the development of eating problems in the future [15].

Because eating problems often emerge among adolescents, the preadolescent years might be an important period of interest related to the development of eating behavior disorders. Feeding and eating disorders have a multifactorial nature and are associated with an interaction between developmental, environmental, and social factors [11, 25]. A responsive feeding style is the optimal approach for parents, which includes an appropriate reaction to children’s feeding behavior. This means honoring both rejection and acceptance of foods, permitting self-feeding by the child, setting appropriate limits, modeling eating, and providing healthy diets [14]. When parents become anxious regarding the weight or food intake of their children, they often utilize controlling feeding behaviors, which include physical prompts, coercive policies (bribes, rewarding), forced feeding, and other pressuring policies [10].

Mosli et al. [16] found that maternal behavior during mealtimes might have an indirect effect on the index child through shaping the behavior of siblings. As controlling feeding strategies can be linked to an enhanced risk of obesity, future studies may assess the complex effect of controlling feeding behaviors on both mothers and siblings.

In previous research, the assessment of parenting practice patterns or styles was dependent mainly on parent reports, which makes it liable to bias. Consequently, personality factors that shape these patterns or styles can be linked to feeding and eating behavioral problems among children and would be more objectively studied. Also, the prevalence of this disorder needs to be assessed in our culture.

Methods

Patients were enrolled in the outpatient clinics at the Pediatric Department, Mansoura University Hospital, during the years 2021–2022. Our study obtained its approval from the local ethical committee of Mansoura University. The sample size was calculated using Medcalc15.8 (https://www.medcalc.org/). The primary outcome of interest is the prevalence of feeding problems in normal children. A previous study found that at least 25% of normally developing children are reported to experience a feeding problem during childhood [4]. With an alpha error of 5%, study power of 80%, and 5% precision, the sample size is 528 normal children.

Inclusion criteria were patients aged between 6 and 12 years old (school age to understand questions) of both genders, diagnosed with feeding disorders according to DSM-5, and whose mothers agreed to sign informed consent.

We excluded patients who were aged below 6 years or above 12 years and had any medical or surgical diseases.

The Control group included an equal number of subjects with matched age (8.63 years versus 8.71 for the cases group with feeding disorders) and gender (51.5% are females versus 41.2% of the cases group). They are healthy children who came without any other medical diseases, just, cold cases like sore throat or cough, or the child’s relatives came with their mothers.

Instruments

Mansoura University Hospital's child psychiatric sheet is a non-structured instrument, including sociodemographic data, medical data, neuropsychiatric history, and examination.

The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINIKID) (Child Version) The MINI-KID interview was designed based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) and the International Classification of Diseases, 10th version (ICD-10). It is divided into diagnostic modules; each module includes screening questions (except for the psychotic disorders module) and diagnostic questions; the diagnostic questions were asked only when the screening questions were positive. All questions were answered “yes or no” [20]. The Arabic version of MINIKID used in our study is approved to be valid [9]. This scale is used to exclude any other psychiatric disorders other than feeding and eating disorders.

The DSM, Fifth Edition, for feeding and eating disorders is used to diagnose feeding and eating disorders [2] (Arabic version) [19].

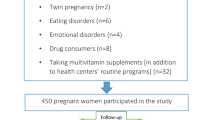

Cattell’s 16 personality factor test (paper questionnaire), developed by Cattell and Mead (1949), is a 185-item measure for normal personality and is currently in its 5th edition. It uses multiple-choice responses to evaluate 16 primary scales, 5 s-order scales, and 2 third-order scales. The questionnaire is available in computer format or paper and pencil format, with a variety of age-adjusted and modified versions to be used in different situations [3] (Arabic version) [1]. An overview of the entire study process is shown.

Cases were collected at sixty days through 1 year with a range of 10 children per day. During their stay at the waiting lounge of the outpatient clinic, they were screened to the three above sheets and questionnaires at 20 min. Each child detected with feeding or eating disorder, his mother was assessed to Cattell’s questionnaire and the time of the interview was about 45 min, then children who appeared matched with the cases, and their mothers were assessed to the same questionnaire.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Corp., released in 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0 Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. Qualitative data were presented as frequencies and percentages. Quantitative data were presented as means and standard deviations for parametric data following testing for normality by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The significance of the result was set at the 0.05 level. The chi-square test was utilized to compare the two groups. A binary stepwise logistic regression analysis was utilized to predict independent variables of the binary outcome. Significant predictors in the Univariate analysis were entered into the regression model utilizing the forward Wald method (Enter). Adjusted odds ratios and the 95% confidence interval were calculated.

Results

Sociodemographic data of the studied group

Five hundred twenty-eight children were screened. The mean age was 8.67 ± 1.93 years. The mean weight was 29.51 ± 7.68 kg. 63.8% of them were in urban settings while 36.2% were rural. They were divided into 53.4% female and 46.6% male (Table 1).

Thirteen percent of the children in the study have eating and/or feeding disorders, with the distribution being as follows: 5.7% have binge eating disorders, 2.5% have avoidant and/or restrictive eating disorders, 1.5% have atypical anorexia nervosa, 0.8% have binge eating disorder (low frequency), 0.8% have night eating syndrome, 0.6% have unspecified feeding or eating disorder and AN, 0.4% have rumination disorder, and 0.2% have pica (Table 2).

There is a significantly higher frequency of anorexia nervosa in females than males, while there is a significantly higher frequency of binge eating in males than females (27.6% versus 18.4%, respectively) (Table 3).

There is a statistically significant association between the presence of certain types of feeding and eating disorders and the age of the studied children, as shown in unspecified feeding or eating disorders, rumination disorder (6.5 and7 years) was found among the youngest age group, and pica was found among the elder age group (9.75 years) (Table 4).

A statistically significant difference was found between certain personality factors of the studied mothers and the presence of feeding and eating disorders among their children, being significant (p < 0.05) among tender-minded, imaginative, forthright, and apprehensive mothers, while the difference was highly significant (p < 0.001) among controlled mothers (Table 5).

Certain personality factors of the mothers can be used as significant predictors (p < 0.001) for feeding and eating disorders among their children, including tender-minded, imaginative, and controlled personality factors, with adjusted odds ratios of 2.56, 3.02, and 3.84, respectively.

Discussion

In viewing the prevalence of feeding and eating disorders among the studied children, 13% of the children have eating and/or feeding disorders, with the distribution being as follows: 5.7% have binge eating disorder, 2.5% have avoidant and/or restrictive eating disorders, 1.5% have atypical anorexia nervosa, 0.8% have binge eating disorder (low frequency), 0.8% have night eating syndrome, 0.6% have Unspecified feeding or eating disorder and AN, 0.4% have rumination disorder, and 0.2% have pica. These results compared to a study by Galmiche et al. [8] who reported that the highest prevalence for EDNOS, followed by BED, BN, and AN according to DSMIV, compared to the new setting of DSM-5, OSFED still has the highest prevalence, followed by BED, BN, and AN, but in the current study no BN was found, which may be attributed to the children’s differences in age range (6–12 years), which make them less likely to engage in compensatory behaviors. Another difference in the current study is the increasing incidence of BED due to children staying at home for long periods because of Corona repercussions.

Regarding the distribution of feeding and eating disorders according to the sex of children in the current study, anorexia nervosa is higher frequency in females than males, while there is a significantly higher frequency of binge eating in males than females (27.6% versus 18.4%, respectively). These results were consistent with the systematic review that evaluated the lifetime prevalence of eating disorders and reported that AN prevalence is 1.4% in women and 0.2% in males. Unlike BED which is the most prevalent disorder affecting 2.8% of females and 1% of males, BN had higher prevalence scores of 1.9% in women and 0.6% in men [8, 13]. All these results should be cautiously considered since the actual community incidence of eating and feeding disorders is not known [12, 21].

Concerning the distribution of feeding and eating disorders according to age in the current study, unspecified feeding or eating disorder and rumination disorder were found among the youngest age group (6.5 and 7 years) while pica was found among the elder age group (9.75 years), comparing to study of Murray et al. [17] who did not find AN cases in American children aged 10–11 years, BN prevalence was insignificant, while the BED prevalence was 1.1%. The prevalence of subclinical AN, BN, and BED was 6%, 0.2%, and 0.5%, respectively,probably the short age range (10–11) in this study is the cause of that difference.

Regarding to relationship between personality factors of the studied mothers and the presence of feeding and eating disorders among their children, no previous study handled what we carried out in our current study like Ystrom et al. [24], who handled the first research project in the world. They analyzed children’s diets combined with both psychological variables and the socio-demographics of the mother and reported that a mother who was emotionally unstable, anxious, angry, sad, had no self-confidence, or had a negative view of the world was far more likely to offer sweet and fatty foods to children. Because these maternal personality characteristics fall under the collective name of high negative affectivity, such mothers usually have lower stress thresholds, giving up rapidly when facing obstacles, e.g., in a disagreement, and usually lose control over their children, so that mothers try to compensate by forcing a healthy diet on the child or by tightly holding sweet foods, or they paradoxically try to balance poor control by actually using more force and limits. They increase desire, which leads to resistance in the form of tantrums, which these mothers are also bad at resisting. These characters could be approximately matched with the studied factors as follows: emotionally unstable meets tender-minded and imaginative; anxious meets tense and apprehensive; angry meets controlled; Sad meets apprehensive; poor self-confidence meets apprehensive and forthright; and a negative view of the world meets apprehensive. These results focus on the effect of these traits, not factors, but we had extra factors in the current study.

Yee et al. [23] found specific parental practices affected child food consumption, which debates with the current study like restrictive guidance, control of availability, and pressure to eat were shaped by control factors, while the practice of modeling and rewarding food consumption materially were shaped by tender-minded factors as in the current study. Paradoxically, he found that parents can offer rewards shrewdly for children with praise rather than material or hedonic rewards (which contrasted forthrightly with the current study), and that praise qualitatively differs from other types of rewards. As Orrell-Valente et al. [18] found, praise fulfills and fosters the intrinsic needs of relatedness, competence, and autonomy when compared with extrinsic rewards.

Limitations

This study was performed only on a limited range of ages 6–12 so we could not take a broad view of the results. Such as certain disorders were not detected, e.g., bulimia nervosa. Mothers who have a low level of education cannot understand some questions, so need some explanation. Long questionnaires (187 questions) made some mothers refuse interviews.

Conclusions

Significant correlations were found between certain personality factors of the studied mothers (controlled, tender-minded, imaginative, forthright, and apprehensive) and the prevalence of feeding and eating disorders in their children, compared with those without feeding and eating disorders.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- 16PF:

-

The Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire

- AN:

-

Anorexia nervosa

- ARFID:

-

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder

- BED:

-

Binge-eating disorder

- BN:

-

Bulimia nervosa

- DSM-5:

-

The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- DSM-IV-TR:

-

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision

- ED:

-

Eating disorder

- EDNOS:

-

Eating disorder not otherwise specified

- OSFED:

-

Other specified feeding or eating disorder

- RD:

-

Rumination disorder

- SPSS:

-

Soft package of social science

- SSBs:

-

Sugar-sweetened beverages

References

Al-Baqai H (2003) The Sixteen Factors Test of Personality - Fifth Edition. J Fed Arab Univ Educ Psychol Syria 1(3):142–178

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. (DSM-5). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association

Bahner CA, Clark CB (2020) Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire (16PF). Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences, pp. 4958–4961

Bryant-Waugh R, Markham L, Kreipe RE, Walsh BT (2010) Feeding and eating disorders in childhood. Int J Eat Disord 43(2):98–111

Chatoor I, Egan J, Getson P, Menvielle E, O’Donnell R (1988) Mother—infant interactions in infantile anorexia nervosa. J Am Acad Child Adolescent Psychiatry 27(5):535–540

Craigie AM, Lake AA, Kelly SA, Adamson AJ, Mathers JC (2011) Tracking of obesity-related behaviours from childhood to adulthood: a systematic review. Maturitas 70(3):266–284

Galloway AT, Fiorito L, Lee Y, Birch LL (2005) Parental pressure, dietary patterns, and weight status among girls who are “picky eaters.” J Am Diet Assoc 105(4):541–548

Galmiche M, Déchelotte P, Lambert G, Tavolacci MP (2019) Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000–2018 period: a systematic literature review. Am J Clin Nutr 109(5):1402–1413

Ghanem MH, Ibrahim M, El-Behairy AA et al (2000) Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for children/adolescents (M.I.N.I. Kid). Arabic version- 1st edn, Cairo, Ain-Shams University, Institute of Psychiatry

Harris HA, Ria-Searle B, Jansen E, Thorpe K (2018) What’s the fuss about? Parent presentations of fussy eating to a parenting support helpline. Public Health Nutr 21(8):1520–1528

Harrison AN, Bateman CCJ, Younger-Coleman NO, Williams MC, Rocke KD, Scarlett SCC-D et al (2019) Disordered eating behaviours and attitudes among adolescents in a middle-income country. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, pp 1–11

Hay P, Mitchison D, Collado AEL, González-Chica DA, Stocks N, Touyz S (2017) Burden and health-related quality of life of eating disorders, including Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID), in the Australian population. J Eat Disord 5(1):1–10

Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG Jr, Kessler RC (2007) The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry 61(3):348–358

Hughes SO, Power TG, Fisher JO, Mueller S, Nicklas TA (2005) Revisiting a neglected construct: parenting styles in a child-feeding context. Appetite 44(1):83–92

Kotler LA, Cohen P, Davies M, Pine DS, Walsh BT (2001) Longitudinal relationships between childhood, adolescent, and adult eating disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 40(12):1434–1440

Mosli RH, Miller AL, Peterson KE, Lumeng JC (2016) Sibling feeding behavior: mothers as role models during mealtimes. Appetite 96:617–620

Murray SB, Ganson KT, Chu J, Jann K, Nagata JM (2022) The prevalence of preadolescent eating disorders in the United States. J Adolesc Health 70(5):825–828

Orrell-Valente JK, Hill LG, Brechwald WA, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE (2007) “Just three more bites”: an observational analysis of parents’ socialization of children’s eating at mealtime. Appetite 48(1):37–45

Shalabi M, Dosoki M, Ibrahim Z (2014) Feeding and eating disorders, Diagnostic guider of psychiatric disorders for adults and children, derived from (DSM-5) (Arabic version) translation group at department of psychology Alminia and Al fayom university. Egyptian Anglo, Cairo

Sheehan DV, Janavs J (1998) 1998) Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for children/adolescents (MINI Kid. University of South Florida, College of Medicine, Tampa

Udo T, Grilo CM (2018) Prevalence and correlates of DSM-5–defined eating disorders in a nationally representative sample of US adults. Biol Psychiat 84(5):345–354

Wright C, Birks E (2000) Risk factors for failure to thrive: a population-based survey. Child Care Health Dev 26(1): 5–16

Yee AZH, Lwin MO, Ho SS (2017) The influence of parental practices on child promotive and preventive food consumption behaviors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 14(1):1–14

Ystrom E, Niegel S, Vollrath ME (2009) The impact of maternal negative affectivity on dietary patterns of 18-month-old children in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study. Matern Child Nutr 5(3):234–242

Zeanah CH, Gleason MM (2015) Annual research review: attachment disorders in early childhood–clinical presentation, causes, correlates, and treatment. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 56(3):207–222

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

There are no sources of funding for the research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A. interviewed the patients, applied the Cattell questionnaire to their mothers, and helped in writing the manuscript. I.H.R.E. analyzed and interpreted the patient data and was a major contributor to writing the manuscript. S.Y. helped in the revision of the manuscript and the results of the study. S.T. helped in the conception of the research idea and revision of the manuscript. All authors revised and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

IRB approval was obtained (MS.20.03.1081).

Consent for publication

Yes.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al Agroudi, A.A.M., Rashed, I.H., Yahia, S. et al. Mothers’ personality and children with feeding and eating disorders: a nested case–control study. Middle East Curr Psychiatry 30, 114 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-023-00384-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-023-00384-4