Abstract

Background

The family is an important social context where children learn and adopt eating behaviors. Specifically, parents play the role of health promoters, role models, and educators in the lives of children, influencing their food cognitions and choices. This study attempts to systematically review empirical studies examining the influence of parents on child food consumption behavior in two contexts: one promotive in nature (e.g., healthy food), and the other preventive in nature (e.g., unhealthy food).

Methods

From a total of 6,448 titles extracted from Web of Science, ERIC, PsycINFO and PubMED, seventy eight studies met the inclusion criteria for a systematic review, while thirty seven articles contained requisite statistical information for meta-analysis. The parental variables extracted include active guidance/education, restrictive guidance/rule-making, availability, accessibility, modeling, pressure to eat, rewarding food consumption, rewarding with verbal praise, and using food as reward. The food consumption behaviors examined include fruits and vegetables consumption, sugar-sweetened beverages, and snack consumption.

Results

Results indicate that availability (Healthy: r = .24, p < .001; Unhealthy: r = .34, p < .001) and parental modeling effects (Healthy: r = .32, p < .001; Unhealthy: r = .35, p < .001) show the strongest associations with both healthy and unhealthy food consumption. In addition, the efficacy of some parenting practices might be dependent on the food consumption context and the age of the child. For healthy foods, active guidance/education might be more effective (r = .15, p < .001). For unhealthy foods, restrictive guidance/rule-making might be more effective (r = −.11, p < .01). For children 7 and older, restrictive guidance/rule-making could be more effective in preventing unhealthy eating (r = − .20, p < .05). For children 6 and younger, rewarding with verbal praise can be more effective in promoting healthy eating (r = .26, p < .001) and in preventing unhealthy eating (r = − .08, p < .01).

Conclusions

This study illustrates that a number of parental behaviors are strong correlates of child food consumption behavior. More importantly, this study highlights 3 main areas in parental influence of child food consumption that are understudied: (1) active guidance/education, (2) psychosocial mediators, and (3) moderating influence of general parenting styles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Food consumption preferences are developed early in life [1]. Understanding how children’s food consumption choices are developed has the potential to benefit individuals’ health over their entire lifetime. Specifically, limiting the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs), while increasing the consumption of healthy food choices such as fruits and vegetables, can have protective effects on people’s health [2, 3]. In spite of this, children across several parts of the world are consuming sugars at an alarming rate, with children in the United States [4, 5], United Kingdom [6], Mexico [7], and even Asian countries such as Taiwan and Singapore [8,9,10] consuming SSBs at worrying levels. To compound the problem of sugar consumption on their diets, the consumption of fruits and vegetables among children is relatively low across the world. In the United States, 60% of children do not consume enough fruits to meet the recommended daily guidelines, while 93% of children do not consume sufficient vegetables [11]. Mirroring the United States, European children are consuming fruits and vegetables below the recommended levels [12].

Parents are important socialization agents who play the role of health promoters, role models, and educators in the lives of their children [13]. Defined as “processes whereby naïve individuals are taught the skills, behavior patterns, values, and motivations needed for competent functioning (p.13)”, socialization in the context of food consumption involves parents conveying learning outcomes such as norms, knowledge, attitudes and behaviors to children via a range of behaviors [14]. Among socialization researchers, two broad concepts have been used to understand parental influence on child outcomes [15]. First, parental practices are context-specific strategies parents use to help children achieve socialization goals. Second, general parenting style, which cuts across behavioral contexts, refers to the general emotional climate in which these parental practices are situated.

Currently, there are no comprehensive systematic reviews surveying the influence of parental practices and parenting styles on child SSBs and fruits and vegetables consumption. Existing reviews have either focused on examining a broad array of determinants of SSBs consumption without an in-depth examination of the role of parents [16, 17], or examined the influence of singular parental practices – such as availability and role modelling – on various child food consumption behavior [18, 19]. Reviews that have focused on parental influence have examined parental practices in only one specific food consumption outcome, namely fruits and vegetables consumption, and these reviews tend not to quantitatively summarize the effect sizes between the parenting variables and child food consumption outcomes [20, 21]. There are currently no meta-analytic studies that aim to provide a quantitative summary of the influence of various parenting variables on child food consumption behavior. To our knowledge, this study would be the first to systematically review the influence of parents in two areas of child food consumption, one promotive (fruits and vegetables consumption) and one preventive (SSBs consumption). Examining the influence of parents in these two areas of child food consumption behaviors can help provide greater clarity of the efficacy of certain parental practices in different contexts.

This paper addresses these gaps in the literature by presenting the results from a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of studies designed to examine the relationship between parental factors (which includes both context-specific parental practices and more general parenting styles) and child food consumption behaviors (SSBs and fruits and vegetables consumption). It attempts to cover a wide spectrum of parental factors believed to shape child food consumption, and examine their influence in two food consumption contexts – one preventive in nature (SSBs consumption) and one promotive in nature (fruits and vegetables consumption).

Methods

The review was conducted in two phases. First, an extensive systematic review of the literature was done to identify the parental factors related to child food consumption behavior. Next, a meta-analysis was conducted following these classifications, with studies which contain the requisite statistical information.

Literature search

In order to find relevant studies of parenting effects on child food cognitions, choice, and intake, a literature search was conducted in the following major databases: Web of Science, PsycINFO, ERIC, and PubMED. The search strategy relied on using a combination of parental factors keywords and child food consumption keywords. Parental factors keywords were matched with a child food consumption keyword for every search. The parental factor keywords were: “parenting”, “parent* communication”, “parent* strateg*”, “parent* style*”, “parent* practice*”, “parent* feed* strateg*”, and “parent* feed* practice*”. The keywords for child food consumption were: “eating”, “food consumption”, “soft drink*”, “sweetened beverage*”, “fruit*”, and “vegetable*”. To ensure comprehensiveness, the reference lists of key articles were hand searched to identify literature not retrieved from the initial search. An initial search was conducted in December 2015. The list of studies was updated with a second round of search in March 2016.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

An article had to fulfill the following criteria to be eligible for inclusion: (1) the subjects of study had to be healthy children or adolescents below the age of 18; (2) the studies had to utilize quantitative methods (surveys and experiments were both included), with statistical significance being reported; (3) the independent variable(s) must contain one parenting practice or style; (4) the dependent variable(s) were either food cognitions such as attitudes (implicit and explicit), liking, preference or social norms, or food consumption choice and/or intake of fruits and vegetables or SSBs.

Articles that were excluded were: (1) articles not published in English; (2) studies that involved only overweight or obese parents and/or children; (3) studies that stratified analyses according to BMI without providing overall effect sizes; (4) studies that examined the dependent variable(s) of eating problems and styles such as eating disorders, disordered eating, and emotional eating, as well as BMI; and (5) intervention studies.

Analytical approach

In the first phase, a three-step process was utilized to identify relevant studies for the systematic review. First, the retrieved papers were screened and shortlisted using their titles. Next, the abstracts of the shortlisted articles were screened in another round of shortlisting. Two reviewers were involved in shortlisting the articles. Overall, percent agreement between the reviewers were at 92%. All disagreements were discussed between the reviewers and resolved by revisiting the inclusion/exclusion criteria and by coming to a consensus. Finally, entire articles were retrieved from the database and screened, with eligible studies being retained for the review. The associations between parenting factors and child eating outcomes were represented with “+” for a significant positive association, “-” for a significant inverse association, and “0” for a null association. Associations with a reported p value of < 0.05 were considered significant. In studies with univariate and multivariate results, the associations considered were taken from the multivariate analysis. Studies with statistical analyses indicating the significance level were included. Mediation and moderation effects are stated in the final column of Additional file 1: Table S1. In stratifying the analysis according to child age, Piaget’s three stages of cognitive development in children was utilized [22]. Parental factors that saw less than 2 studies conducted within a developmental stage were omitted from the analysis.

As there were no standardized terminologies for parental factors, with researchers often utilizing conflicting definitions with regard to similar terms, we attempted to develop a list of overarching parental constructs by examining each study’s operationalized measurement items. First, we examined all the measures used across every study. Next, we grouped the measurement items into arbitrarily named parental practice variables based on face validity. When operationalized measurement items grouped together came from a wide range of differently named constructs (across different researchers), the variable they represent were given a new term in order to avoid confusion (e.g., parental encouragement through rationale and parent nutrition teaching were classified under active guidance). On the other hand, when a group of measures representing a variable were derived from a commonly used term, the term was retained (e.g., modeling). Once all the factors were identified and named, two reviewers classified the measures in each included study based on the identified constructs. Percent agreement between the two reviewers were at 91% overall. Disagreements were resolved through a discussion between the reviewers.

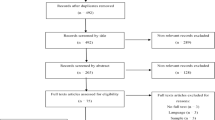

In the second phase, a meta-analysis was conducted for studies that were eligible for the calculation of effect sizes using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis 2 software. In order for studies to be included in the meta-analysis, the quantitative information required for computation of overall effect size, such as sample sizes, means, correlations, odds ratios and test statistics must have been available. Studies without these required information were excluded. In order to generate overall effect sizes, data from studies that included correlations, means with standard deviations, or odds ratios were converted into Pearson’s product–moment correlation scores, resulting in commensurable effect sizes across studies. The conversions were executed using established formulas [23]. Studies utilizing Spearman correlation coefficients were also included, as Spearman correlation coefficients are equivalent or only slightly smaller as compared to Pearson’s product–moment correlation scores [24]. These correlation coefficients were then weighted according to the corresponding study’s sample size and standard error, resulting in a weighted correlation score [25]. Following that, the overall effect sizes of each predictor and outcome were calculated by averaging the weighted correlation coefficients across the eligible studies. As some studies utilized a combination of food items within a single category as dependent variables (e.g., fruits and vegetables as separate measures), the meta-analysis was conducted by averaging the correlations between an independent variable and the dependent variables within a category, so that only a single correlation score is computed for either healthy or unhealthy food consumption.Footnote 1 This meta-analysis was conducted using random effects models. An a priori assumption guided this choice. Since studies included in this analysis were not identical, it was not possible to assume a true effect size across the studies. The studies were conducted independently across different age groups of children, and across different cultural contexts, indicating that the use of random effects models was more appropriate in the analysis [26]. Figure 1 displays a PRISMA flowchart illustrating the systematic process of conducting the review.

Results

A total of 6448 titles were located from the literature search (Web of Science = 1692; ERIC = 190; PsycINFO = 708; PubMED = 3858). After removing duplicates, there were a total of 2237 unique titles potentially relevant for inclusion in this review. After screening the titles, 556 articles were retained for abstract screening. Following that, 158 full-text articles were retrieved and scanned in their entirety for eligibility, with 82 articles being retained for analysis. Six articles were added after hand searching the reference lists of relevant articles, resulting in a total of 88 articles utilized in this review. A summary of the studies can be viewed in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Characteristics of included studies

Most of the studies were cross-sectional studies (n = 66), with the rest being longitudinal (n = 14), experimental (n = 5), and quasi-experimental (n = 3). 49% of the studies involved children in the pre-operational stage (ages 2 to 6; n = 43), 33% involved those in the concrete operational stage (ages 7 to 11; n = 29), while only 16% of the studies involved those in the formal operational stage (ages 12 to 18; n = 16)Footnote 2 [22]. Most studies were situated in the US, Europe, and Australia, with the exception of three studies: one being situated in Israel, one in Costa Rica, and another in Hong Kong. The spread of parent-report (n = 33), child-report (n = 28), and parent-child matched samples (n = 27) were evenly matched. Despite this, most studies with parent-report measures consisted of a large number of female participants.

With regard to specific target food items being examined, 64% of studies examined parental influence on fruits/vegetables consumption (n = 56), 24% examined SSBs consumptionFootnote 3 (n = 21), 51% examined some form of unhealthy eatingFootnote 4 (n = 45), and 10% examined healthy foods consumptionFootnote 5 (n = 9). Since specific food items (eg. fruits/vegetables, SSBs) were measured in the composite measures of general healthy and unhealthy food consumption, the subsequent analysis of the effects of parenting on child food consumption considered them under the concepts of healthy (promotive) and unhealthy (preventive) food consumption.

A total of 10 parental factors were identified from the literature. They included context-specific parental practices of restrictive guidance (or rule-making) (n = 48), modeling (or parents’ own food consumption behavior) (n = 37), availability (or the control of availability) (n = 36), parental pressure to eat (n = 25), food as reward (n = 12), rewarding food consumption (n = 10), rewarding food consumption with praise (n = 9), accessibility (n = 6), and active guidance (or verbal education and encouragement) (n = 5). Meanwhile, the effects of general parenting styles were examined in 18% of the studies (n = 16).

Context-specific parental practices and child food consumption

Restrictive guidance

Restrictive guidance is defined as the frequency with which parents set limits, rules, or restrictions regarding food consumption. Closely related to the parental mediation dimension of restrictive mediation [27], this includes a range of overt parental restriction constructs such as rule-making and parental overt control. Among the included studies, 33 examined the relationship between parental restrictive guidance and healthy eating such as fruits and vegetables intake. Amongst these, 13 indicated a positive relationship with healthy eating, three yielded a negative relationship, whilst 17 indicated a non-significant relationship. For unhealthy eating such as the consumption of SSBs, restrictive guidance was found to reduce consumption in 16 out of 38 studies. Eight studies suggested that parental restrictive guidance is associated with higher consumption of unhealthy foods among children, while 14 studies indicated a null relationship. This suggests a large amount of heterogeneity in the relationship between restrictive guidance and both healthy and unhealthy child food consumption behaviors.

Modeling

Modeling was measured in two ways across the literature. First, modeling was measured as parental intake of a target food item. In such a case, a positive relationship between parent and child intake was indicative of a significant modeling effect. Second, modeling was measured as the frequency in which parents eat healthily and demonstrate the benefits and pleasure of eating healthily in front of children. In both cases, modeling was consistently found to be associated with child eating. Among the 31 studies that examined modeling and healthy food consumption, 28 found a significant positive relationship, while three saw no significant association. Among the 16 studies that examined modeling and unhealthy food consumption, 13 showed a significant positive association, while three saw no significant association. This suggests that the effects of parental modeling on child food consumption behavior are homogenous and significant.

Parental control of availability

Parental control of availability simply refers to whether a particular food is available at home. Since children develop food preferences through consistent exposure to foods [28,29,30], the availability of food would be crucial in determining whether children develop healthy food preferences rather than energy-dense food preferences such as SSBs. Availability was measured in two ways across the reviewed studies. First, it was measured with regards to actual availability of a target food item (this can be measured as availability or non-availability of a target food). Second, it was measured as a parental strategy that involves parents controlling the availability of unhealthy foods in a covert manner [31,32,33].

Among the 27 studies examining availability of healthy foods and healthy foods consumption, an overwhelming 19 studies indicated a positive association, whilst 5 indicated a null relationship. Likewise, availability of healthy food, non-availability of unhealthy foods, as well as parental control of availability of unhealthy foods, were associated with decreased unhealthy eating in 18 out of 22 studies. Three studies indicated a null relationship. These results suggest that availability or control of food availability can be a consistent predictor of child food consumption.

Pressure to eat

Parents can also pressure children into eating more food [34]. This practice refers to parents utilizing verbal communication to try and persuade their children to consume more food. Pressure can manifest in a parent asking his or her child to clean up their plates, even if the child says he or she is not hungry [35]. Underlying parental pressure to eat is a fear that a child is not consuming enough food. Although parents’ intention when utilizing pressure is to encourage sufficient nutrient intake, some researchers have argued that it can have the opposite effect, leading to lower fruits and vegetables intake [36, 37]. Of the 22 studies that examined pressure to eat and healthy food consumption, 14 showed no significant associations. Six studies found significant negative associations, where pressure was shown to be associated with less healthy food consumption. Only two studies found a positive association. With regards to unhealthy food consumption, eight studies showed that pressuring a child to eat was associated with significantly higher unhealthy food intake, while 13 studies showed that there were no significant associations.

Food as reward

Parents might also utilize food as a reward when children exhibit desirable behavior. Three studies found a negative association between using food as reward and healthy food consumption, with the large majority of studies (n = 7) finding no significant relationships between the two variables. In contrast, six out of ten studies that examined the influence of food as reward on unhealthy eating found a positive relationship. As unhealthy foods such as sweet snacks are most often used as the reward item, this practice tends to increase preferences for unhealthy foods [38, 39]. However, less is known about how the utilization of healthy foods such as fruits and vegetables as reward can influence child food consumption outcomes.

Rewarding food consumption materially

Rather than using food as a form of reward, parents can sometimes reward healthy food consumption with material or playtime rewards [39, 40]. According to self-determination theory [41, 42], providing extrinsic rewards for an activity can potentially decrease the motivation and desire to perform the activity. When a reward is provided for eating a certain food, a child will tend to devalue the instrumental activity performed to receive the reward, as the child will see the activity as a means to an end [43]. In other words, if eating healthy food is the only way a child can get to play outside, the child might see it as a chore, and subsequently hold negative mental associations, feelings, and cognitions about the food.

Out of 10 studies, most studies (n = 6) found no significant relationships between rewarding food consumption and child healthy eating. Three studies found a positive association, while one study found a negative association. Among the four studies that examined the relationship between rewarding food consumption and unhealthy eating, one study found a positive association. This positive association could be due to a single item in the composite measure of rewarding food consumption belonging conceptually closer to using food as reward (e.g., dessert as contingent upon eating something the child doesn’t like) [44].

Rewarding with praise

Parents can reward children with praise rather than material or hedonic rewards. Some researchers have suggested that praise is qualitatively different from other types of rewards [40], likely because praise fulfills and fosters the intrinsic needs of relatedness, competence, and autonomy, as compared to extrinsic rewards. Among seven studies that examined the relationship of praise with healthy food consumption, four found positive relationships, while three yielded non-significant results. With regards to unhealthy eating, one study found that praise was associated with savory snack consumption among girls only, while the other studies (n = 4) found no significant relationships.

Accessibility

Parental control of food accessibility refers to “whether the foods are prepared, presented, and/or maintained in a form that enables or encourages children to eat them (p. 26) [45]”. Six studies examined the relationship between making food accessible and child fruits/vegetables intake. Four studies indicated a positive relationship, while two indicated a null relationship, suggesting that accessibility can potentially be a useful parental strategy in encouraging healthy eating.

Active guidance

Active guidance or education is defined as the degree which parents actively discuss, verbally interact, and instruct their child with regards to food. Only five studies examined the influence of active guidance on child food consumption. In these studies, the measures indicating active guidance were encouragement through rationale (e.g., eating vegetables is good for you) [44], or nutritional teaching regarding types of food [46]. Amongst the studies, one found a positive relationship between active guidance and vegetables consumption, as well as a negative relationship between active guidance and SSBs consumption. However, the four other studies have indicated a non-significant relationship between active guidance and healthy or unhealthy eating.

General parenting styles and moderation effects

Parenting researchers recognize that individual context-specific parenting behaviors are a part of a complex milieu of other parenting behaviors, so no individual parenting practice (eg. such as the use of active guidance) can be isolated and tested for its influence without considering other facets of parenting [15]. In view of this, general styles of parenting can be viewed as a circumstantial construct that would moderate the influence of context-specific parenting behaviors such as active parental guidance, using food as reward, pressuring children to eat and so on [47,48,49]. This perspective adopts the view that context-specific parenting practices can have different effects when employed by families who utilize a different parenting style [50].

In general, most studies reviewed examined the direct relationship between parenting variables and child food consumption outcomes. Only approximately 10% (n = 9) of all the articles reviewed examined the moderating influence of general parenting styles, indicating a lack of empirical understanding about the complex influence of parenting styles on the effects of parenting practices. Amongst those that examined parenting styles as a moderator, one noted that restrictive guidance situated in an authoritarian parenting style showed stronger effects on fruits intake, whilst availability situated in an authoritative parenting style showed stronger effects on fruits and vegetables intake [51]. Another study utilizing parental feeding style as a moderator supported this, as they found that restrictive guidance led to lower intake of low-nutrient-density foods among less permissive parents [52]. One study found that restrictive guidance had stronger positive associations with healthy eating, and stronger negative associations with unhealthy eating when parental warmth is high, suggesting that whilst demandingness/control might lead to more effective restrictive guidance, warmth can also play a role in moderating the effects in the same direction [53]. Another echoed these findings, as they found that restrictive guidance and availability were more strongly associated with lower child SSBs intake amongst children with highly responsive, as well as moderately demanding parents [54]. Other studies contradicted these findings. Specifically, one study found that children under an indulgent parental feeding style (low in demandingness, high in responsiveness) saw greater positive relationship between restrictive guidance and fruits and vegetables consumption [49]. Likewise, two other studies found that restrictive guidance was associated with lower SSBs intake only when behavioral control was low among parents [55, 56].

Other than its moderating effects on restrictive guidance, one study found that the strongest associations between modeling and child fruit consumption occurred among children who were under a highly controlling parenting style [55]. Another study also found that controlling the availability of food was also more effective in reducing SSBs intake amongst children of parents who reported higher control [56]. Of all nine studies, only one study found no moderating effect from parenting styles [57].

Cognitive mediators of food consumption

Five studies sought to examine the influence of parenting on food cognitions such as preference [58], liking [59, 60], subjective norms [61], desire [62], and attitudes [57, 61]. Although all five studies indicated some level of significant relationships between parenting variables and food cognitions, mediation through these cognitions were not tested statistically. Only one reviewed study examined potential psycho-social mediators between parenting variables and child food consumption [63]. In the study, the researchers found that self-efficacy partially mediated the effects of modeling on fruits and vegetables consumption.

Differences by child age

Eighty-six studies were included in the stratified analysis of studies based on child age. Two studies were omitted as there was insufficient information regarding the mean age of the children being referred to available within the full-text article. Table 1 summarizes the findings of the studies being reviewed, according to child age. Interestingly, some age differences can be observed.

First, all three studies that examined restrictive guidance among older children in the formal operational stage (FOS) found no significant associations with healthy food consumption. This was in contrast to studies with younger children in the pre-operational stage (POS) and concrete operational stage (COS), where a large amount of heterogeneity exists, and with a substantial proportion of studies finding a significant positive relationship (40 and 35% respectively). Interestingly, a greater proportion of studies showed that restrictive guidance had a negative relationship with unhealthy food consumption among children in FOS (83%), as compared to those in the COS (45%) and POS (29%).

Unsurprisingly, a greater proportion of studies among older children (COS compared to POS) found a positive relationship between active guidance and healthy food consumption, and a negative relationship between active guidance and unhealthy food consumption. This suggests that active guidance might be more useful in shaping food consumption behaviors with children that are at a more advanced developmental stage. Unfortunately, there were no studies that involved children in the FOS for comparisons.

More studies appear to show the undesirable effects of pressuring a child to eat among younger children. 36% of the studies involving children in POS found a negative relationship with healthy food consumption, while 55% found a positive relationship with unhealthy food consumption. However, for samples involving older age groups, a vast majority of studies found no significant relationship between pressuring and both types of food consumption. Rewarding food consumption either with praise or with tangible rewards appear to be more effective in promoting healthy eating among younger children in the POS, with 50% of the studies finding a positive relationship between rewarding food consumption and healthy food consumption, and 80% finding a positive relationship between rewarding with praise and healthy food consumption. However, these significant findings were non-existent among those in the COS.

Meta-analysis findings

In addition to the preceding systematic review, a smaller subset of 37 studies with available statistics was utilized to conduct a quantitative meta-analysis. Except for the relationship between accessibility and unhealthy food consumption, all relationships had at least two eligible studies, allowing us to compute a meta-analytic effect size for each relationship between variables. As illustrated in Table 2, five out of the nine parental communication variables had a statistically significant weighted correlation with child healthy food consumption. Specifically, active guidance (r = .15, p < .001), availability (r = .24, p < .001), modeling (r = .32, p < .001), and verbal praise (r = .15, p < .05) were significantly and positively correlated with child healthy food consumption. The effect sizes were small to medium according to guidelines developed by Cohen [64, 65]. In addition, pressuring children to eat had a small but significant negative correlation with child healthy food consumption (r = −.04, p < .05). Restrictive guidance, accessibility, and rewarding food consumption were not significantly correlated with child healthy food consumption.

With regards to child unhealthy food consumption, six out of the nine identified parental communication variables were significantly correlated with unhealthy food consumption (See Table 3). Specifically, restrictive guidance (r = −.11, p < .01), and verbal praise (r = −.04, p < .05) had small but significant negative correlations with child unhealthy food consumption. On the other hand, availability (r = .34, p < .001), modelling (r = .35, p < .001), pressure to eat (r = .04, p < .05), and using food as reward (r = .14, p < .05) were positively correlated with child unhealthy food consumption. Active guidance and rewarding food consumption were not significantly correlated with child unhealthy food consumption.

Meta-analysis moderated by child age

In addition to the systematic review suggesting some age differences, a significant Q statistic suggests that there was heterogeneity in the effect sizes between studies [66]. As such, examining age as a moderator in the analysis could reveal potential differences. Among the nine parental communication variables, active guidance, rewarding food consumption and using food as reward did not have heterogeneous results across study in the context of child healthy food consumption, thus they were excluded from the analysis. Likewise, reward with verbal praise and food as reward were excluded from the analysis in the context of child unhealthy food consumption due to it fulfilling the assumption of homogeneity. Additionally, active guidance was excluded from the analysis as there were only two studies available for moderator analyses. Table 4 and 5 summarizes the results of the meta-analysis moderated by child age.

The results showed that although availability had a significant positive relationship with healthy food consumption across all age groups, it had a stronger association with healthy food consumption among older children. However, this ought to be read with caution, as among the FOS group, only one study was utilized in the analysis. Echoing the results of the systematic review analyses stratified by child age, the undesirable effects of parental pressuring on healthy food consumption was found only among younger children, and not older children. Likewise, the positive associations between rewarding with verbal praise and healthy food consumption existed only among younger children, and not older children.

With regard to unhealthy food consumption, the results indicated that restrictive guidance was more effective in reducing unhealthy food consumption among older children. In addition, rewarding desirable eating behavior with verbal praise had a negative association with unhealthy food consumption only among younger and not older children.

Discussion

The systematic review of parental factors and child promotive and preventive food consumption outcomes yielded a total of 10 potential parental factors, 9 of which captured context-specific parental factors, and one of which referred to parenting styles as a moderating factor. Of these, availability or the control of availability of food items, along with parental modeling were consistently associated with both desirable and undesirable food consumption cognitions and consumption. This was supported by both the systematic review and the meta-analysis. First, meta-analytic procedures found that they had the strongest correlations with both child healthy and unhealthy food consumption. Second, the systematic review found that a vast majority of studies support the direction of relationship as indicated in the meta-analysis. Parents availing food can increase consumption from the possibility that children eat whatever that is available to them.

In addition, parental modeling could possibly convey attitudinal, norms-based, and self-efficacy beliefs to children, which drives consumption behavior [67]. According to social cognitive theory, modeling refers to the process whereby an individual (in this case a child) learns through his or her observations of another person performing a behavior [68, 69]. Specifically, it is hypothesized that a child will imitate or adopt behaviors when they observe an influential role model in their lives (e.g., a parent) perform said behaviors. Modeling effects take place because observations of other people eating will influence their own beliefs about what to eat, and how much is appropriate to eat [70]. In addition, some researchers have defined modeling as a type of parental communication strategy, consisting of parental encouragement for their children to adopt their own behaviors intentionally through overt verbal communication and covert non-verbal strategies [71,72,73]. Specifically, modeling can also occur when parents explicitly display to their children that they enjoy certain food items, leading to a child’s vicarious learning about the enjoyment of eating certain food types. Such explicit displays of eating behaviors are used as a parenting strategy to promote attitudes toward, and subsequently, consumption of certain foods among children. Our systematic review reveals that both types of modeling are similarly associated with more desirable eating behaviors.

Restrictive guidance was found to be negatively associated with unhealthy food consumption, while its association with healthy food consumption was mixed. This was supported by both the systematic review and meta-analysis. When the analyses were stratified by age, an interesting pattern emerged. While the association of restrictive guidancewith healthy food consumption was mixed for younger children, studies with children older than 12 found no evidence for such an effect. This suggests that restrictive guidance might be ineffective in promoting desirable food choices among older children. However, it is interesting to note that the relationship between restrictive guidance and unhealthy food consumption was more powerful among older children, as compared to those in the POS. It is possible that younger children in the POS are less able to follow rules or limits set out by parents due to limited self-regulation capabilities [74]. Future research is suggested to better understand why this phenomenon exist.

Next, using food as reward was found to be related to higher levels of unhealthy eating among children. This was supported in both the systematic review and meta-analysis. This is likely due to the fact that foods used as rewards are often unhealthy. By rewarding children’s behavior with these unhealthy food items, children might associate these unhealthy items as positive and valuable, hence consuming more of them when they have the chance [75].

Pressuring children to eat can lead to effects unintended by the parents. Although a small number of studies found a positive association between pressuring and healthy eating, a larger number of studies found a negative association. In addition, seven studies showed that pressuring can be associated with higher unhealthy food consumption. This is also played out in the meta-analysis, with pressuring being shown to have a small negative correlation with healthy food consumption and small positive correlation with unhealthy food consumption. However, age-stratified analyses revealed that these unintended effects tend to be limited to younger children, as the effects are non-significant in studies involving older children.

The evidence that rewarding food consumption can influence child food consumption was weak, as most studies included in the systematic review showed no significant effects. The meta-analysis also showed no significant correlation between rewarding food consumption and child food consumption. On the other hand, a larger proportion of studies found that verbal praise might lead to higher healthy foods consumption, indicating that rewarding with material rewards and praise are distinct practices with different outcomes. However, it is important to note that rewarding with praise appeared to be more useful with younger children in the POS, with the effects diminished in studies involving older children.

Although the number of studies examining accessibility was small, the majority of studies in the systematic review indicated that accessibility can have a positive influence on healthy foods consumption. This was not supported in the meta-analysis, as there was a non-significant correlation between accessibility and child healthy food consumption. One reason for this discrepancy might be due to the limited number of studies included in the meta-analysis.

Interestingly, active guidance received very little attention from researchers, with only 6% of the studies treating it as a potential predictor of child food consumption. Despite this, research in the domain of parental mediation has found active discussion to be an effective parental socialization technique in influencing desirable child outcomes [76]. The meta-analysis results suggest that these effects might translate well into the child food consumption context, as there was a small to medium, positive, and significant relationship between active guidance and child health food consumption. One reason for the modest findings could be that the existing measures are inadequate in capturing the concept of active guidance in its entirety. Existing concepts that were used as proxies for active guidance in this study were teaching about nutrition and encouragement through rationale [44, 77]. These constructs are more closely related to factual parental guidance, as opposed to evaluative parental guidance. Factual active guidance refers to informing children with technical knowledge. Such techniques have been found to be ineffective in mitigating negative media effects on children [78, 79]. Evaluative active mediation, on the other hand, reflects parents’ attempts to provide either positive or negative opinions about a topic, and are considered to be a more effective strategy [79]. Examining the influence of evaluative, rather than factual parental guidance, might yield stronger associations. A second reason could be that there were insufficient studies examining the effect of active guidance on older children. Our age-stratified systematic review analysis found that the beneficial effects of active guidance were more pronounced in studies involving older children in COS, as compared to those in POS. However, only 3 studies out of the 88 unique studies examined active guidance among children older than 7.

Opportunities for future research

The systematic review has identified several gaps in the study of parental communication and child food consumption. First, although some parental communication practices were consistently linked with child food consumption outcomes (e.g., modeling and availability), many of the other parental communication practices show mixed results (e.g., restrictive guidance) and some are severely understudied (e.g., active guidance). More research needs to be conducted in these areas to ascertain the relationships between parental communication and child food consumption behavior. Second, the concept of active guidance is currently underdeveloped and understudied. Although active discussions have been shown to be an effective parental communication strategy in socializing children to more desirable outcomes in other contexts [76], there remains a lack of understanding of how parents’ active verbal discussions with children apply in the food consumption context. Specifically, there has been a lack of conceptual explication of parental guidance in the food consumption context, with existing studies not taking into account the different facets of parental guidance. Existing studies have examined active parental guidance from the perspective of factual guidance (e.g., teaching about nutritional facts). As previous studies have found factual guidance to be less effective than evaluative guidance, future studies should attempt to examine evaluative guidance as a correlate. Existing studies also do not take into account how positive or negative active guidance can influence outcomes. As healthy eating choices are to be promoted, and unhealthy eating choices are to be discouraged, active guidance as dichotomized into positive vs. negative can have differential impact. Positive active guidance might be more effective in promoting healthy eating, and less effective in discouraging unhealthy eating. This is suggested in our meta-analysis results where active guidance (which reflect a more positive construct in the operationalization across studies) was found to be correlated with healthy eating but not unhealthy eating. Third, theoretically-driven studies of parental communication on child food consumption, which takes into account psychosocial mediating variables, are severely lacking. The systematic review found that only five studies attempted to understand child food consumption from such a perspective. Without considering the social psychological processes of the child, it is difficult to ascertain the pathways of how certain parental practices are influencing child food consumption behavior. This means that current understanding of parental communication on child food consumption is incomplete.

Limitations

There are several limitations of this study that should be taken into account when drawing conclusions from the results. First, the review was conducted using a non-exhaustive list of studies. Although effort was made to be comprehensive in the retrieval of articles by searching through four major databases and hand-searching relevant articles, there could have been some studies that were missed out on. To minimize this, we hand-searched the reference list of every selected study, which helped ensure greater comprehensiveness in the systematic review. Despite this, it is important to note that the conclusions are drawn from overall trends across studies, rather than from singular studies, rendering a small number of missed articles less consequential. Second, most of the studies were limited to populations in the west. As nuances in parent-child relationships might exist across cultures, the findings might not generalize across to cultures outside of the west. Lastly, there is a lack of uniformity in measuring a number of these parental variables. Despite this, our efforts to synthesize and categorize the variables have yielded strong agreement rate between two coders. Nonetheless, it is important to note that in several of these studies, there is strong heterogeneity in terms of operationalizing some of these variables, limiting their comparability.

Conclusion

There is a wide variety of behaviors that parents engage in to either promote or prevent certain child food consumption behaviors. Some behaviors, such as parents’ own food consumption behavior, and availing certain types of food, have been shown to be strong correlates of child food consumption behavior. On the other hand, some behaviors such as active and restrictive guidance, are effective only in certain contexts; active being more effective in encouraging fruits and vegetables consumption, while restrictive guidance is more effective in discouraging unhealthy eating such as SSBs consumption. Despite this, there appears to be a number of research gaps that needs to be filled. Researchers in the field can take note of the opportunities for future research highlighted from this comprehensive study. In doing so, we can better understand what constitutes an ideal family environment that helps improve the wellbeing of our children.

Notes

For example, if Study A examined the effects of restrictive guidance on fruits and vegetables consumption and found their correlations as r = .15 and r = .25, the correlations would be averaged (\( \frac{.15+.25}{2} \) = .20), such that a single r = .20 is used to represent restrictive guidance of food consumption’s correlation with healthy food consumption.

Articles were grouped into these three groups of developmental stages using the mean age of the children under study

Including high-energy drinks

Including unhealthy snacks, low-nutrient density food, junk foods, and non-core foods; some of these composite measures of unhealthy eating consisted of a component of SSBs consumption

Including core-foods and healthy snacking (eg. fruits as snacks)

References

Ventura AK, Worobey J. Early influences on the development of food preferences. Curr Biol. 2013;23:R401–8.

Ludwig DS, Peterson KE, Gortmaker SL. Relation between consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks and childhood obesity: a prospective, observational analysis. Lancet. 2001;357:505–8.

Malik VS, Pan A, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98:1084–102.

Welsh JA, Sharma AJ, Grellinger L, Vos MB. Consumption of added sugars is decreasing in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:726–34.

Cullen KW, Ash DM, Warneke C, De Moor C. Intake of soft drinks, fruit-flavored beverages, and fruits and vegetables by children in grades 4 through 6. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1475–8.

Department of Health and the Food Standards Agency. National diet and nutrition survey [internet]. 2011. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/216484/dh_128550.pdf.

Barquera S, Hernandez-Barrera L, Tolentino ML, Espinosa J, Ng SW, Rivera JA, et al. Energy intake from beverages is increasing among mexican adolescents and adults. J Nutr [Internet]. 2008;138:2454–61. Available from: http://jn.nutrition.org/cgi/doi/10.3945/jn.108.092163.

Pan W-H, Wu H-J, Yeh C-J, Chuang S-Y, Chang H-Y, Yeh N-H, et al. Diet and health trends in Taiwan: comparison of two nutrition and health surveys from 1993–1996 and 2005–2008. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr [Internet]. 2011;20:238–50. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21669593.

Yamada K. S’pore children drinking sugary drinks too frequently: HPB [internet]. yourHealth (AsiaOne). 2012. Available from: http://yourhealth.asiaone.com/content/spore-children-drinking-sugary-drinks-too-frequently-hpb.

Goh DYT, Jacob A. Children’s consumption of beverages in Singapore: knowledge, attitudes and practice. J Paediatr Child Health [Internet]. 2011;47:465–72. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21332593.

Kim SA, Moore L V, Galuska D, Wright A, Harris D, Grummer-Strawn LM, et al. Vital signs: Fruit and vegetable intake among children - United States, 2003–2010 [Internet]. Centers Dis Control Prev Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6331a3.htm?s_cid=mm6331a3_w.

Lynch C, Kristjansdottir AG, Te Velde SJ, Lien N, Roos E, Thorsdottir I, et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption in a sample of 11-year-old children in ten European countries--the PRO GREENS cross-sectional survey. Public Health Nutr [Internet]. 2014;17:2436–44. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25023091.

Case A, Paxson C. Parental behavior and child health. Health Aff [Internet]. 2002;21:164–78. Available from: http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.164.

Maccoby EE. Historical overview of socialization research and theory. In: Grusec JE, Hastings PD, editors. Handb. Social. Theory Res. New York: Guilford Press; 2014. p. 3–34.

Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychol Bull. 1993;113:487–96.

Mazarello Paes V, Hesketh K, O’Malley C, Moore H, Summerbell CD, Griffin S, et al. Determinants of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in young children: a systematic review. Obesi16ty Rev. 2015;16:903–13.

Rasmussen M, Krølner R, Klepp K-I, Lytle L, Brug J, Bere E, et al. Determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among children and adolescents: a review of the literature. Part I: quantitative studies. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act [Internet]. 2006;3:22. Available from: http://www.ijbnpa.org/content/3/1/22.

Cook LT, O’Reilly GA, DeRosa CJ, Rohrbach LA, Spruijt-Metz D. Association between home availability and vegetable consumption in youth: a review. Public Health Nutr [Internet]. 2015;18:640–8. Available from: http://www.journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S1368980014000664.

Wang Y, Beydoun MA, Li J, Liu Y, Moreno LA. Do children and their parents eat a similar diet? Resemblance in child and parental dietary intake: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Heal [Internet]. 2011;65:177–89. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3010265/.

Pearson N, Biddle SJH, Gorely T. Family correlates of fruit and vegetable consumption in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr [Internet]. 2009;12:267–83. Available from: http://www.journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S1368980008002589.

van der Horst K, Oenema A, Ferreira I, Wendel-Vos W, Giskes K, van Lenthe FJ, et al. A systematic review of environmental correlates of obesity-related dietary behaviors in youth. Health Educ Res [Internet]. 2006;22:203–26. Available from: http://www.her.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/doi/10.1093/her/cyl069.

Ginsburg HP, Opper S. Piaget’s theory of intellectual development. 3rd edition. Englewood Cliffs, Prentice-Hall; 1988.

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Converting among effect sizes. Introd. to meta-analysis [internet]. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2009. p. 45–9. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/9780470743386.ch7.

Gilpin AR. Table for conversion of Kendall’S Tau to Spearman’s Rho within the context of measures of magnitude of effect for meta-analysis. Educ Psychol Meas [Internet]. 1993;53:87–92. Available from: http://epm.sagepub.com/cgi/doi/10.1177/0013164493053001007.

Hedges LV, Olkin I. Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Orlando: Academic; 1985.

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods [Internet]. 2010;1:97–111. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/jrsm.12.

Valkenburg PM, Piotrowski JT, Hermanns J, Leeuw R. Developing and validating the perceived parental media mediation scale: a self-determination perspective. Hum Commun Res. 2013;39:445–69.

Birch LL, McPhee L, Steinberg L, Sullivan S. Conditioned flavor preferences in young children. Physiol Behav [Internet]. 1990;47:501–5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2359760.

Birch LL. Children’s preferences for high-fat foods. Nutr Rev [Internet]. 1992;50:249–55. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1461587.

Birch LL. Development of food preferences. Annu Rev Nutr. 1999;19:41–62.

Boots SB, Tiggemann M, Corsini N, Mattiske J. Managing young children’s snack food intake. The role of parenting style and feeding strategies. Appetite. 2015;92:94–101.

Brown KA, Ogden J, Vögele C, Gibson EL. The role of parental control practices in explaining children’s diet and BMI. Appetite [Internet]. 2008;50:252–9. Netherlands: Elsevier Science, Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0195666307003315.

Durao C, Andreozzi V, Oliveira A, Moreira P, Guerra A, Barros H, et al. Maternal child-feeding practices and dietary inadequacy of 4-year-old children. Appetite. 2015;92:15–23.

Scaglioni S, Salvioni M, Galimberti C. Influence of parental attitudes in the development of children eating behavior. Br J Nutr [Internet]. 2008;99:22–5. Available from: http://www.journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0007114508892471.

Birch LL, Fisher JO, Grimm-Thomas K, Markey CN, Sawyer R, Johnson SL. Confirmatory factor analysis of the child feeding questionnaire: a measure of parental attitudes, beliefs and practices about child feeding and obesity proneness. Appetite [Internet]. 2001;36:201–10. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0195666301903988.

Galloway AT, Fiorito L, Lee Y, Birch LL. Parental pressure, dietary patterns, and weight status among girls who are “picky eaters. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:541–8. 2005/04/01.

Fisher JO, Mitchell DC, Smiciklas-Wright H, Birch LL. Parental influences on young girls’ fruit and vegetable, micronutrient, and fat intakes. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:58–64.

Birch LL, Fisher JO. Development of eating behaviors among children and adolescents. Pediatrics [Internet]. 1998;101:539–49. Available from: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/101/Supplement_2/539.

Savage JS, Fisher JO, Birch LL. Parental influence on eating behavior. J Media Law Ethics. 2007;35:22–34.

Orrell-Valente JK, Hill LG, Brechwald WA, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. “Just three more bites”: an observational analysis of parents’ socialization of children’s eating at mealtime. Appetite [Internet]. 2007;48:37–45. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0195666306005137.

Deci EL, Ryan RM. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum; 1985.

Deci EL, Ryan RM. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inq. 2000;11:227–68.

Birch LL, Marlin DW, Rotter J. Eating as the “means” activity in a contingency: effects on young children’s food preference. Child Dev [Internet]. 1984;55:431. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1129954?origin=crossref.

Vereecken CA, Keukelier E, Maes L. Influence of mother’s educational level on food parenting practices and food habits of young children. Appetite [Internet]. 2004;43:93–103. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0195666304000431.

Hearn MD, Baranowski T, Baranowski J, Doyle C, Smith M, Lin LS, et al. Environmental influences on dietary behavior among children: availability and accessibility of fruits and vegetables enable consumption. J Heal Educ. 1998;29:26–32.

Melbye EL, Hansen H. Promotion and prevention focused feeding strategies: exploring the effects on healthy and unhealthy child eating. Biomed Res Int. 2015;306306:7. Available from: http://www.hindawi.com/journals/bmri/2015/306306/.

Kremers SPJ, Sleddens EFC, Gerards S, Gubbels J, Rodenburg G, Gevers D, et al. General and food-specific parenting: measures and interplay. Child Obes. 2013;9:S22–31.

Larsen JK, Hermans RCJ, Sleddens EFC, Engels RCME, Fisher JO, Kremers SPJ. How parental dietary behavior and food parenting practices affect children’s dietary behavior. Interacting sources of influence? Appetite. 2015;89:246–57.

Papaioannou MA, Cross MB, Power TG, Liu Y, Qu H, Shewchuk RM, et al. Feeding style differences in food parenting practices sssociated with fruit and vegetable intake in children from low-income families. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2013;45:643–51.

Koerner AF, Fitzpatrick MA. Family communication patterns theory: a social cognitive approach. In: Braithwaite DO, Baxter LA, editors. Engag. Theor. Fam. Commun. Mult. Perspect. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2006. p. 50–65.

De Bourdeaudhuij I, te Velde SJ, Maes L, Perez-Rodrigo C, de Almeida MDV, Brug J. General parenting styles are not strongly associated with fruit and vegetable intake and social-environmental correlates among 11-year-old children in four countries in Europe. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12:259–66.

Hennessy E, Hughes SO, Goldberg JP, Hyatt RR, Economos CD. Permissive parental feeding behavior is associated with an increase in intake of low-nutrient-dense foods among American children living in rural communities. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112:142–8.

Ray C, Kalland M, Lehto R, Roos E. Does parental warmth and responsiveness moderate the associations between parenting practices and children’s health-related behaviors? J Nutr Educ Behav. 2013;45:602–10.

van der Horst K, Kremers SPJ, Ferreira I, Singh A, Oenema A, Brug J. Perceived parenting style and practices and the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages by adolescents. Health Educ Res [Internet]. 2007;22:295–304. Available from: http://www.her.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/doi/10.1093/her/cyl080.

Rodenburg G, Oenema A, Kremers SPJ, van de Mheen D. Parental and child fruit consumption in the context of general parenting, parental education and ethnic background. Appetite. 2012;58:364–72. 2011/11/19.

Sleddens EFC, Kremers SPJ, Stafleu A, Dagnelie PC, de Vries NK, Thijs C. Food parenting practices and child dietary behavior. Prospective relations and the moderating role of general parenting. Appetite. 2014;79:42–50. 2014/04/15.

Taylor A, Wilson C, Slater A, Mohr P. Parent- and child-reported parenting. Associations with child weight-related outcomes. Appetite. 2011;57:700–6.

Bante H, Elliott M, Harrod A, Haire-Joshu D. The use of inappropriate feeding practices by rural parents and their effect on preschoolers’ fruit and vegetable preferences and intake. J Nutr Educ Behav [Internet]. 2008;40:28–33. Available from: http://www.jneb.org/article/S1499-4046(07)00135-2/abstract.

Cooke LJ, Chambers LC, Anez EV, Croker HA, Boniface D, Yeomans MR, et al. Eating for pleasure or profit: the effect of incentives on children’s enjoyment of vegetables. Psychol Sci. 2011;22:190–6. 2010/12/31.

Corsini N, Slater A, Harrison A, Cooke L, Cox DN. Rewards can be used effectively with repeated exposure to increase liking of vegetables in 4-6-year-old children. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16:942–51. 2011/09/09.

de Bruijn GJ, Kremers SPJ, de Vries H, van Mechelen W, Brug J. Associations of social-environmental and individual-level factors with adolescent soft drink consumption: Results from the SMILE study. Heal Educ Res Res. 2007;22:227–37. 2006/08/02.

Jansen E, Mulkens S, Jansen A. Do not eat the red food!: Prohibition of snacks leads to their relatively higher consumption in children. Appetite. 2007;49:572–7.

Young EM, Fors SW, Hayes DM. Associations between perceived parent behaviors and middle school student fruit and vegetable consumption. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2004;36:2–12.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 1992;1:98–101.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

Rosenthal R. Meta-analytic procedures for social research. Newbury Park: Sage; 1991.

Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Heal Educ Behav. 2004;31:143–64.

Bandura A. Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychol Health [Internet]. 1998;13:623–49. Available from: [cited 2014 Jul 29], http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/08870449808407422.

Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:1–26.

Herman CP, Polivy J. Normative influences on food intake. Physiol Behav. 2005;86:762–72.

Musher-Eizenman DR, Holub S. Comprehensive feeding practices questionnaire: validation of a new measure of parental feeding practices. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:960–72.

Vaughn AE, Tabak RG, Bryant MJ, Ward DS. Measuring parent food practices: a systematic review of existing measures and examination of instruments. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:61. Available from: http://www.ijbnpa.org/content/10/1/61.

Palfreyman Z, Haycraft E, Meyer C. Development of the Parental Modelling of Eating Behaviors Scale (PARM): links with food intake among children and their mothers. Matern Child Nutr. 2014;10:617–29.

Kopp CB. Antecedents of self-regulation: a developmental perspective. Dev Psychol. 1982;18:199–214.

Birch LL, Zimmerman SI, Hind H. The influence of social-affective context on the formation of children’s food preferences. Child Dev. 1980;51:856–61.

Buijzen M. The effectiveness of parental communication in modifying the relation between food advertising and children’s consumption behavior. Br J Dev Psychol. 2009;27:105–21.

Melbye EL, Bergh IH, Hausken SES, Sleddens EFC, Glavin K, Lien N, et al. Adolescent impulsivity and soft drink consumption: the role of parental regulation. Appetite [Internet]. 2015;96:432–42. Elsevier Ltd, Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.09.040.

Nathanson AI, Yang MS. The effects of mediation content and form on children’s responses to violent television. Hum Commun Res. 2003;29:111–34.

Nathanson AI. Factual and evaluative approaches to modifying children’s responses to violent television. J Commun. 2004;54:321–36.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was part of AY’s dissertation and is not funded by any external sources.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included as Additional files 2 and 3.

Authors’ contributions

AzhY conceived the study, carried out the design, literature search, data extraction, data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. MoL and SsH participated in discussing the paper, and contributed to refining the study design, providing theoretical and methodological input, and helped revise the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Andrew Z. H. Yee is a PhD candidate at Nanyang Technological University’s Wee Kim Wee School of Communication. His research focuses on the role of parents and other socialization agents in children’s health outcomes. Andrew is the recipient of the prestigious Nanyang President’s Graduate Scholarship, and has received a number of awards in various health communication and nutrition conferences.

May O. Lwin (PhD, National University of Singapore, 1997) is an Associate Professor of Strategic and Health Communication at the Wee Kim Wee School of Communication & Information, Nanyang Technological University and an Associate Dean (Special Projects) at the College of Humanities, Arts & Social Sciences. Her research focuses on the intersection between digital technology, health and well-being with attention on families and children. She has won numerous awards and led a number of large scale projects involving health, wellness and nutrition.

Shirley S. Ho (PhD, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2008) is an Associate Professor in the Wee Kim Wee School of Communication and Information at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Her research focuses on the use of social media and digital media technologies in communicating science and health issues to children, adolescent, and adult populations.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Summary of studies included in the systematic review. (PDF 402 kb)

Additional file 2:

Meta-analysis dataset. Cleaned meta-analysis dataset. (XLSX 15 kb)

Additional file 3:

Database of all studies included in this review. This database allows for filtering of the studies according to the age group of children. (XLSX 47 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Yee, A.Z.H., Lwin, M.O. & Ho, S.S. The influence of parental practices on child promotive and preventive food consumption behaviors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 14, 47 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0501-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0501-3