Abstract

Background

Psoriasis is associated with several comorbidities and different psychological disorders including anxiety and depression. Psoriasis may also affect sleep quality and consequently the quality of life. The use of immunosuppressants used in the treatment of psoriasis were also reported to increase insomnia, so the purpose of the study is to assess the quality of sleep and degree of insomnia in patients with psoriasis not on any systemic or immunosuppressive therapy compared to controls and to examine the relation between sleep quality, insomnia with depressive, and anxiety symptoms. One hundred psoriasis cases, not receiving immunosuppressive therapy, and 80 apparently healthy subjects were recruited as controls. We assessed quality of sleep, insomnia and screened for anxiety and depressive symptoms among psoriasis patients and healthy controls; any patient on immunosuppressant therapy was excluded.

Results

Quality of sleep using Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, insomnia using Insomnia Severity Index, depression using Beck Depression Inventory, and anxiety using Taylor Anxiety Manifest Scale were statistically significant higher among psoriasis patients than healthy controls all with p value p < 0.001. Depressive symptoms were significantly positively correlated with Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) global score (p = 0.045) and subjective sleep quality subscale (p = 0.005). Also, BDI scores was significantly positively correlated with insomnia scores as measured by ISI (p = 0.026).

Anxiety symptoms were significantly positively correlated with global score of PSQI (p = 0.004) and its subscale (subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep disturbance, use of medications and daytime dysfunction) and insomnia (p = 0.001).

Conclusions

Abnormal sleep quality and insomnia were detected in patients with psoriasis not using any immunosuppressive or systemic therapy, and this could be due to the psoriasis disease itself or due to the associated anxiety and depression associated with psoriasis. Screening for psychiatric symptoms specially that of depression, anxiety, and sleep among patients with psoriasis is of utmost importance for better quality of life. Thus, collaboration between dermatologists and psychiatrists may show better life quality for these cases and better treatment outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Psoriasis is a chronic recurrent inflammatory skin disorder with genetic background, environmental factors, and immune system disturbances [1]. However, it is now well known that it is a systemic disease with inflammation that affects several organs in the patient. One of the most important comorbidities are obesity, cardiovascular disease and arthritis. This inflammation was also accused to be the cause of several psychiatric disorders with all of their negative effects on the quality of life of patients. Sleep is an essential physiological status for all human beings and any disturbance may have terrible impact. Several studies have also shown the association of abnormal sleep quality in patients with psoriasis. The cause of this association could be the skin disease itself due to the inability of psoriatic skin to decrease the core body temperature which is required for sleep initiation [2]. Moreover, the associated depression may result in sleep deprivation or fragmentation which may affect the immunological status especially nocturnal cytokine release. Kallikrein-5, Kallikrein 7, IL-1B, Il-6, and IL-12 were potentiated with lack of sleep. Elaborating the effect of sleep deprivation all with depressive and anxiety symptoms on psoriasis may help improving the quality of life of these patients and may aid in finding different therapeutic interventions [1]. There is a bidirectional impact between psoriasis and sleep deprivation. Both were found to be associated with inflammatory cytokines as IL-6 and thus psoriasis may worsen the sleep quality and the poor sleep quality may worsen the psoriasis [3].

The exact cause of sleep disturbance in psoriasis is likely to be multifactorial. So, the aim of the current work was to assess the quality of sleep and degree of insomnia in patients with psoriasis not on any systemic or immunosuppressive therapy compared to controls. The second aim was to examine the relation between sleep quality, anxiety and depression symptoms. Paving the way to reach the different factors that may be the cause of this disturbed sleep and so helping in its cure.

Methods

One hundred psoriasis cases including both Males and Females, age range from 18 to 60 were recruited from Kasr Al Ainy Psoriasis Unit (KAPU) dermatology department between May 2019 and December 2019. Moreover, 80 apparently healthy subjects were recruited as control group. Included cases were only on topical therapies as emollients and combined topical vitamin D analogues and steroids.

Any participants on any immunosuppressive treatment were excluded as well as subjects with any renal disease, infectious disease, malignant disease, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, and pregnant ladies.

All cases were subjected to the following:

Psoriasis grading

All cases were evaluated using psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) which is a scale for the degree of psoriasis where the erythema, induration and scaling of the lesions are given different grades from 0 to 4 according to their severity in different body parts (head, trunk, upper, and lower limbs) and then the surface area in each body part is assessed. The PASI scale ranges from 0 to 72 [4] and body surface area (BSA) which is another severity score measuring the total surface area affected by psoriasis in the skin of the patient using the patient’s hand unit as a measure for 1% of the surface area of each person [5]. PASI less than 10 and body surface area less than 10 were considered as mild [6].

The effect of psoriasis on daily activities, work or school, relationships, leisure, and treatment were assessed using the psoriasis disability index questionnaire (PDI) [7].

Quality of sleep was assessed

Using the Arabic version of Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [8] which is a self-administrated questionnaire, measures the pattern and quality of sleep in adults by assessing seven components; subjective sleep quality, latency of sleep, duration of sleeping, habitual sleep efficiency, disturbances of sleep, whether or not sleep medications are used, and dysfunction of the following day over the last month. Each component is scored from 0 to 3, resulting in a global PSQI score between 0 and 21, with higher scores indicating lower quality of sleep. The PSQI was useful in identifying good and poor sleepers [9].

Insomnia was assessed using Arabic version of Insomnia severity index (ISI). It measures perceived insomnia severity. It consists of seven items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = not at all and 4 = extremely), with a total score ranging from 0 to 28 [10]. ISI score of 0–7 was defined as absence of clinically significant insomnia, ISI score of 8–14 was defined as subthreshold insomnia, ISI score of 15–21 was defined as moderate clinical insomnia and ISI score of 22–28 was defined as severe clinical insomnia.

Depression was assessed using the Arabic version of Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [11], it is a self-reported scale which is suitable for people 13 years or older. It has 21 statements (each has a 4-grade scale) and the individuals should choose the grade that best describes their statuses. The final score range from 0 to 63. The scoring range is as follows:

-

1–10____________________These ups and downs are considered normal

-

11–16___________________ Mild mood disturbance

-

17–20___________________Borderline clinical depression

-

21–30___________________Moderate depression

-

31–40___________________Severe depression

-

Over 40__________________Extreme depression

Anxiety was assessed using the Arabic validated version of Taylor Manifest Anxiety Scale [12]. The scale measures trait anxiety levels, it consists of 50 questions. Anxiety level was assessed as follows: normal (score of 0–16), mild (17–20), moderate (21–26), severe (27–29), and very severe (30–50).

Sample size

Based on a previous study by Melikoglu [13], the mean global PSQI in the patient’s group was 7.01 ± 4.19 and in the control group was 4.18 ± 2.76 to detect the true difference between groups with a power of 90% and a level of significance of 5%, and effect size of 0.7 a minimum sample size of 88 participants will be needed (i.e., 44 for each group will be needed, to compensate for possible 25% will be added, therefore a total sample size of 110 participants will be needed (i.e., 55 participants for each group). The sample size was calculated by G*Power (version 3.1.9.2; Germany).

Data were coded and entered using the statistical package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Data was summarized using mean, standard deviation, median, minimum and maximum in quantitative data, and using frequency (count) and relative frequency (percentage) for categorical data. Comparisons between quantitative variables were done using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test. For comparing categorical data, chi-square (χ2) test was performed. Exact test was used instead when the expected frequency is less than 5. Correlations between quantitative variables were done using Spearman correlation coefficient. P values less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

Demographic and clinical data

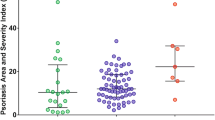

Patients

One hundred patients and 80 healthy controls completed this study. Demographic data of all recruits as well as statistical differences between patients and controls are presented in Table 1. Table 1 showed also the mean PASI score among patients group was 4.97 ± 5.24 and BSA % was 9.98 ± 12.32.

Quality of sleep and insomnia among cases and control groups

Results of ISI for patients and controls are demonstrated in Table 2. The mean scores were 9.50 ± 6 and 3.48 ± 4.85 for patients and controls respectively and this was statistically significant (p < 0.001). This results showed that patients group suffered from insomnia more than controls.

Also, Table 3 showed PSQI scores which assessed sleep quality, there was a highly statistical significant difference between both groups as regards the global score and its subscales measuring (subjective sleep quality, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbance, use of sleep medications, and day time dysfunction). These results showed that patients group suffered from poor quality sleep more than controls.

Depression assessment for cases and control groups

Results of Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) for patients and controls are demonstrated in Table 3. The mean scores BDI test were 20.93 ± 10.75 and 3.48 ± 3.42 for patients and controls respectively and it was statistically significant higher among patients group (p < 0.001), indicating that patients group suffer more from depressive symptoms.

Anxiety assessment for cases and control groups

Results of Taylor Manifest Anxiety Scale for patients and controls are demonstrated in Table 3. The mean results of the scale were 26.65 ± 8.71 and 6.40 ± 5.78 for patients and controls respectively and this was statistically significant (p < 0.001), indicating more anxiety symptoms among patients group.

As regards percentage only 10% of controls had mild depressive and anxiety symptoms in comparison to 80% of cases that showed different severities of depression and 82% showed different severities of anxiety.

Correlations

As shown in Table 4, there were statistically significant positive correlation between ISI and PDI, also there were statistically significant positive correlation between sleep latency, sleep disturbance and use of sleep medication and BMI, on the other hand there was statistically negative correlation between habitual sleep efficiency and BSA. Depressive and anxiety symptoms measured by BDI and Taylor Manifest Anxiety Scale were significantly positively correlated with PDI.

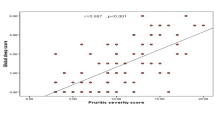

In Table 5, depressive symptoms measured by BDI were significantly positively correlated with Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) global score and subjective sleep quality subscale. Also, BDI scores was significantly positively correlated with insomnia scores as measured by ISI.

Anxiety symptoms as measured by Taylor Manifest Anxiety Scale were significantly positively correlated with global score of PSQI and its subscale (subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep disturbance, use of medications, and daytime dysfunction)

Discussion

In this current study, we excluded psoriasis patients on any immunosuppressant therapy or systemic therapy to exclude their effect on sleep quality. We found a significant disturbance in sleep quality as measured by PSQI and insomnia severity as measured by ISI in these psoriasis patients when compared to controls. Moreover, sleep quality and insomnia severity among them were positively correlated with depressive and anxiety symptoms.

Different studies have investigated the sleep affection in patients with psoriasis. Samaci et al. 2019 recruited sixty psoriasis cases with mean PASI scores of 10.1 ± 9.7 which was slightly higher than ours (4.97 ± 5.24) and showed statistically significant changes in daytime sleepiness, sleep quality and insomnia severity index when compared to controls. Similar to our findings the latter authors did not find any correlation between the severity or duration of psoriasis and the degree of sleep affection. However, it has been previously reported that psoriasis itself may negatively affect sleep due to its negative effect on the person’s circadian rhythm regulating body temperature. For sleep to start, there must be a slight lowering in one’s body temperature which does not occur in psoriasis due to an impairment in heat transmission [14]. Surprisingly, according to the current work and that of Samaci et al. 2019, it seems that nor severity nor extent of psoriasis are related to the disease effect on body temperature regulation. On the other hand, while Karjewska-Wlodarczyk et al. [15] showed that 57.7% of psoriasis patients had sleep disorders when compared to 14.6% only among healthy controls, unlike our findings and that of Samaci et al. 2019, this sleep affection was related to the severity of psoriasis, but the study included patients with psoriatic arthritis as well.

Moreover, Sahin et al. [16] recent work showed statistically significant sleep affection in psoriasis cases when compared to controls and this affection was related to the degree of itching that they suffered from as well as the degree of anxiety and depression.

Chronic deterioration of sleep quality decreases the quality of life and may cause cardiovascular and metabolic disorders. Short duration of sleep affection also raises the inflammation in the form of elevation in TNF-alpha, C-reactive protein, and IL-17. Treatment of this decreased sleep quality should be treated by psychotherapy and treating the underlying cause [15]. The skin barrier may get disturbed from depriving a person just one night sleep and may increase IL-1 beta and TNF-alpha. Subclinical shifting in the basal normal cytokine levels may lead to future metabolic syndrome as the decreased sleep stimulates the autonomic nervous system. Itchy, painful psoriatic lesions as well as psoriatic arthritis together with the degree of affection of the emotional well-being and not the percentage of body surface area affected by psoriasis are all causes of disturbed sleep [17]. It is essential that this disturbed sleep quality among psoriasis patients be treated together with treating the underlying cause [15].

As the use of an immunosuppressant therapy in lung transplant patients contributed to their insomnia [18], we excluded patients on such medications in the current study to avoid any confounding factor that may alter the relationship between psoriasis and insomnia.

Interestingly while the relation between psoriasis and physical disability has previously been demonstrated [19], poor sleep quality was associated with higher risk of physical impairment and disability in older adults [20]. As we detected positive correlations between psoriasis disability index and insomnia, anxiety, and depression, this relation association needs further research and insights into the management of the skin as well as its impact on the psychological and physical functions of patients.

Conclusions

In the current study, there was affection of sleep quality and insomnia in patients with psoriasis not on any immunosuppressive or systemic therapy, and this could be due to the psoriasis disease itself or due to the inflammatory effect of associated depression and anxiety. Detection of sleep problems and screening of any depressive and anxiety symptoms is recommended to be in the follow up routine with the patients. Psychoeducation about sleep hygiene should be aimed for to improve psoriasis patient’s quality of life.

Limitations and further recommendations

Larger sample is needed with different types of psoriasis patients to be included to compare between different subtypes and different levels of severity to assess the quality of sleep among them and to study different factors affecting it. Also, the need for further researches to study the effect of sleep on psoriasis patients not suffering from depression and anxiety as well as not on any immunosuppressive or systemic therapy.

Availability of data and materials

Upon request

Abbreviations

- PASI:

-

Psoriasis Area and Severity Index

- BSA:

-

Body Surface Area

- PDI:

-

Psoriasis Disability Index

- PSQI:

-

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

- BDI:

-

Beck Depression Inventory

- ISI:

-

Insomnia Severity Index

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

References

Hirotsu C, Rydlewski M, Araoujo MS, Tufik S, Andersen ML (2012) Sleep loss and cytokine levels in an experimental model of psoriasis. PLoS One 7(11):e51183

Gupta MA, Simpson FC, Gupta AK (2016) Psoriasis and sleep disorders: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev 29:63–75

Nowowiejska J, Baran A, Flisiak I (2021) Mutual relationship between sleep disorders, quality of life and psychological aspects in patients with psoriasis. Front Psychiatry 12:674460. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.674460

Feldman SR, Krueger GG (2005) Psoriasis assessment tools in clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis 64:ii65–ii68

Ogdie A, Shin DB, Love TJ, Gelfand JM (2021) Body surface area affected by psoriasis and the risk for psoriatic arthritis: a prospective population-based cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford):keab622. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keab622 Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34508558

Finlay A (2005) Current severe psoriasis and the rule of tens. Br J Dermatol 152:861–867. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06502.x

Lewis VJ, Finlay AY (2005) Two decades experience of the psoriasis disability index. Dermatology 210:261–268

Suleiman K, Hadid LA, Duhni A (2012) Psychometric testing of the Arabic version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (A-PSQI) among coronary artery disease patients in Jordan. J Nat Sci Res 2(8):15–20

Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ (1989) The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 28(2):193–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 PMID: 2748771

Suleiman KH, Yates BC (2011) Translating the insomnia severity index into Arabic. J Nurs Scholarsh 43:49–53

Abdel-Khalek A (1998) Internal consistency of an Arabic Adaptation of the Beck Depression Inventory in four Arab countries. Psychol Rep 82:264–266

Fahmi M, Ghali M, Meleka K (1977) Arabic version of the personality scale of manifest anxiety. Egypt Psychiatry 11:119–126

Melikoglu M (2017) Sleep quality and its association with disease severity in psoriasis. Eurasian J Med 49(2):124

Sacmaci H, Gurel G (2019) Sleep disorders in patients with psoriasis: a cross-sectional study using non-polysomnographical methods. Sleep Breath 23:893–898

Karjewska-Wlodarczyk M, Owkzarczyk-SaczoneK A, Placek W (2018) Sleep disorders in patients with psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis. Reumatologia 56(5):301–306

Sahin E, Hawro M, Weller K, Sabat R, Philipp S, Kokolakis G, Christou D, Metz M, Maurer M, Hawro T (2022) Prevalence and factors associated with sleep disturbance in adult patients with psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 36(5):688–697. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.17917 Epub 2022 Mar 8. PMID: 35020226

Gupta MA, Gupta AK (2013) Sleep-wake disorders and dermatology. Clin Dermatol 31:118–126

Rohde KA, Schlei ZW, Katers KM, Weber AK, Brokhof MM, Hawes DS, Radford KL, Francois ML, Menninga NJ, Cornwell R, Benca R, Hayney MS, Dopp JM (2017) Insomnia and relationship with immunosuppressant therapy after lung transplantation. Prog Transplant 27(2):167–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/1526924817699960

El-Komy MHM, Mashaly H, Sayed KS, Hafez V, El-Mesidy MS, Said ER, Amer MA, AlOrbani AM, Saadi DG, El-Kalioby M, Eid RO, Azzazi Y, El Sayed H, Samir N, Salem MR, El Desouky ED, Zaher HAE, Rasheed H (2020) Clinical and epidemiologic features of psoriasis patients in an Egyptian medical center. JAAD Int 1(2):81–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdin.2020.06.002 PMID: 34409325; PMCID: PMC8362248

Campanini MZ, Mesas AE, Carnicero-Carreño JA, Rodríguez-Artalejo F, Lopez-Garcia E (2019) Duration and quality of sleep and risk of physical function impairment and disability in older adults: results from the ENRICA and ELSA cohorts. Aging Dis 10(3):557–569. https://doi.org/10.14336/AD.2018.0611 PMID: 31165000; PMCID: PMC6538215

Acknowledgements

None

Funding

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ola Osama Khalaf: methodology (choosing tools), correcting psychometric tools used in the study, data collection, and sharing in manuscript writing and corresponding author. Mohamed M. El-Komy: research idea, supervision on the research process, and revising the manuscript. Dina B. Kattaria: collecting controls and revising manuscript. Marwa S. El-Mesidy: research idea, methodology, collecting cases, and sharing in manuscript writing. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Dermatology Ethics Committee (Date: April 2019 /No. 37/2019). All subjects signed written informed consents to participate in the study.

Consent for publication

Agree

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khalaf, O.O., El-Komy, M.M., Kattaria, D.B. et al. Sleep quality among psoriasis patients: excluding the immunosuppressive therapy effect. Middle East Curr Psychiatry 30, 30 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-023-00305-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-023-00305-5