Abstract

Hydrodynamic behaviour of slip flow and radially applied exponential time-dependent pressure gradient in a curvilinear concentric cylinder is examined. A two-step method of solution has been utilized in resolving the governing momentum equation. Accordingly, the exact solution of the time-dependent partial differential equation is derived in terms of the Laplace parameter. Afterwards, the Laplace domain solution is then inverted to time domain using a numerical-based inverting scheme known as Riemann-sum approximation. The effect of various dimensionless parameters involved in the problem on the Dean velocity, shear stresses and Dean vortices is discussed with the aid of graphs. It is found that maximum Dean velocity is due to an exponentially growing time-dependent pressure gradient and slip wall coefficient. Stability of the Dean vortices is achieved by suppressing time, wall slippage and inducing an exponentially decaying time-dependent pressure gradient.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Flow through curved geometry is of general importance due to its enormous application in fluid engineering, biofluid mechanics and haemodynamics. This can be ascribed to its practical use in most of the systems in the aforementioned fields of endeavour. For instance, in diaphragm pumps and dialysis machines, flow is due to pulsation within the curved tube rather than convective current. It is widely known that the underlying principle of convective-driven flows has its setbacks as heat alters the rheological properties of some fluids. Consequently, it will be desirable to model and design pressure-propelled systems. The hydrodynamic behaviour of fluids in curvilinear geometries is a prevalent concept which emanates from stability/instability of the radial pressure gradient, aspect ratio and curvature of the geometry.

Dean [1] initiated the investigation on steady laminar flow in a curved channel with azimuthal pressure gradient. Afterwards, a considerable number of works have dealt with investigations of the effects of slip boundaries on Taylor–Couette and Dean flows for various flow conditions [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. Theoretical analysis on the flow of viscid incompressible fluid driven by an oscillating pressure gradient in a straight circular pipe and coaxial cylinders was proposed by references [10,11,12]. Reference [13] numerically examined the impact of aspect ratio on Dean hydrodynamics instability. Gupta et al. [14] simulated the flow of cerebrospinal fluid in the human spinal cavity by presenting analytical solution responsible for pulsatile viscous flow driven by a harmonically oscillating pressure gradient in a straight elliptic annulus.

Exact solution for unsteady rotating flow of a generalized Maxwell fluid in an infinite straight circular cylinder with oscillating pressure gradient was reported by Zheng et al. [15]. They concluded that as time increases, the velocity increases as it attains its maximum, before decreasing and the oscillating pressure gradient leads to the fluctuations of the velocity. The hydrodynamic stability of Dean formation has been examined semi-analytically as applied to artificial neural network by reference [16]. Thermal and hydrodynamic effect of nanofluid flowing in a curved annulus with radial azimuthal pressure gradient has been studied by Avramenko et al. [17].

It is important to notice that exponential pressure gradient plays a vital role in flow through channels as well as annulus. Such flow aids in better understanding many technological and industrial problems. In general, this phenomenon generates pressure gradient flow which is not constant but pulsates in some way about a nonzero pressure gradient. In view of that, Yen and Chang [18] examined the effect of time-dependent pressure gradient on magnetohydrodynamic flow in a channel in which three cases of time-dependent pressure gradient were considered, namely periodic, step and pulse pressure gradient. Numerical modelling of unsteady flow with time-dependent pressure gradient using one-dimensional Navier–Stokes Equation (NSE) was reported by Azad and Andallah [19]. Other related articles can be seen in references [20,21,22,23].

In slip flow regime, the heat and mass transfer effect of magnetohydrodynamic fluid flow with slip velocity was scrutinized by Gambo and Gambo [24]. Jha and Yahaya [25] examined the impact of wall slippage in a curvilinear annulus induced by azimuthal pressure gradient. The instability of Dean flow and slip condition in a rotating cylinder was analysed by Avramenko et al. [26]. Authors of reference [27] explored the effect of partial slippage on a rotating flow of hydromagnetic micropolar nanoparticles flowing through a disk. These authors reported that the classical effect of slip jump is in achieving a more amplified velocity profile.

Lately, the transient flow behaviour of viscous incompressible fluids in curvilinear annulus driven by azimuthal pressure gradient, radially oscillating time-dependent pressure gradient and exponential time-dependent pressure gradient has been inspected by authors of references [28,29,30,31,32]. Here, the equation governing the flow has been resolved semi-analytically with the aid of classical Laplace transformation and Riemann-sum approximation (RSA) as a tool for numerical inversion. The behaviour of the Dean velocity, drag and most importantly Dean vortices has been inspected. The result has shown that time plays a role in promoting the flow. In addition, the effect of the oscillating and exponentially decreasing time-dependent pressure gradient is to retard the flow. Authors of references [33,34,35] also utilized Laplace transformation and Riemann-sum approximation (RSA) in treatment of the governing equations. Relevant articles relating to the study may be found in references [36,37,38,39,40,41].

The review of the above-mentioned literature suggests that transient flow formation of viscid incompressible fluid in a curvilinear annulus due to a decaying/growing exponential time-dependent pressure gradient with effects of slip condition has not been discussed yet and the present exploration will bridge this gap. Moved by its fascinating practical application in the fields of biofluids mechanics and engineering, we set out to analyse the effect of slip boundary and exponentially decreasing/increasing time-dependent pressure gradient on Dean formation to obtain an empirical result for the Dean velocity, Dean drag and vortices of the fluids in curved annulus. It is anticipated that our results can be beneficial in accurate design and fabrication of real-time propulsion systems.

Methods

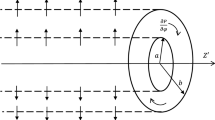

Unsteady hydrodynamically fully developed flow of viscid incompressible fluid in a curved annulus formed by two infinite concentric cylinders is considered. The two cylinders are assumed to be fixed and the fluid is Newtonian. The axis of the cylinder is taken in the \(z^{\prime}\) direction. The radii of the inner and outer cylinder are \(r_{1}\) and \(r_{2}\), respectively, as depicted in Fig. 1. Initially, at time \(t^{\prime} \le 0\), the fluid is assumed to be at rest. At \(t^{\prime} > 0\), the flow is examined under the action of applied radial exponential time-dependent pressure gradient \(\left( {\frac{{\exp \left( { - \delta_{0} t^{\prime}} \right)}}{r^{\prime}}\frac{\partial P}{{\partial \varphi }}} \right)\) in the annular gap. The effect of slip condition on the surface of the two walls was taken into account. Two types of dependence on time are considered: one, exponentially decaying and the other exponentially growing.

Under these assumptions, the continuity equation is satisfied when fully developed flow condition across the \(z^{\prime}\)-axis of the curved annular duct is valid for the function of the radial coordinate and time only, \(u^{\prime} = u^{\prime}\left( {r^{\prime},t^{\prime}} \right)\). In line with Jha and Gambo [31, 32], the dimensional representation of the momentum equation describing the flow is given as:

The initial and boundary conditions for the problem under consideration are

Dimensionless analysis

In transforming Eqs. (1)–(3) to their respective dimensionless forms, we introduced the following dimensionless variables:

Based on Eqs. (1) and (2), the momentum equation governing the flow of the system in dimensionless form is defined as:

with initial and boundary conditions

Analytical solution

In order to derive the transient solution of the governing momentum equation in (5), the classical Laplace transformation has been adopted in transforming the time-dependent equation. Utilizing \(\overline{U}\left( {R,s} \right) = \mathop \smallint \limits_{0}^{\infty } U\left( {R,t} \right)e^{ - st} {\text{d}}t\) where \(s\) \((s > 0)\) is the Laplace parameter, Eqs. (5) in Laplace domain is:

with the accompanied boundary condition in Laplace domain

In line with the approach of Tsangaris and Vlachakis [12] and Jha and Gambo [31, 32], the non-homogeneous linear differential equation in (7) yields the transformation below:

where \(\overline{U}_{h} \left( {R,s} \right)\) is the homogeneous solution of Eq. (7).

With account of boundary conditions (8), the exact solution of Eq. (7) in Laplace domain has been resolved by substituting the homogeneous solution of Eq. (7) into Eq. (9) and is given below as:

where \(B_{1}\) and \(B_{2}\) are defined in the “Appendix” section.

The skin drag at the surface of the inner and outer cylinders are computed by taking the derivative of Eq. (10) and setting \(R = 1\) and \(R = \lambda\), respectively. Thus, the expressions are given as follows:

Dean vortices \(\overline{\eta }\left( {R,s} \right)\) otherwise known as fluid vorticity which is produced in the annular region due to the rotation of the fluid as a result of the curved nature of the geometry is computed by differentiating Eq. (10) and is given below as:

Riemann-sum approximation (RSA)

It is imperative to note that the expression for Dean velocity, skin drag and vortices in (10)–(13) are in the Laplace domain and are to be transformed in order to determine the Dean velocity, skin frictions and vorticity in time domain. In order to achieve this, we employ the Riemann-sum approximation (RSA) approach. Details of this method of numerical Laplace inversion are given in references [31,32,33,34,35]. The Riemann-sum approximation (RSA) is remarkable for its accuracy when inverting Laplace domain functions to time domain. Based on this approach, any function of the Laplace domain can be transformed to time domain using the expression below:

where \({\text{Re}}\) is the real part of the summation, \(i\) the imaginary number, \(Q\) is the number of terms involve in the summation and \(\varepsilon\) is the real part of the Bromwich contour that is used in inverting Laplace transform. The Riemann-sum approximation (RSA) for the Laplace inversion involves a single summation for the numerical computation, of which its exactness is dependent on the value of ε and the truncation error prescribed by \(M\). Following Tzou [42], taking εt to be 4.7, ensures the stability of the computation.

The approach used in deriving the time domain solution is validated by presenting a numerical comparison of the present result obtained under no-slip boundary condition with Jha and Gambo [32] (see Tables 1 and 2).

Results and discussion

An analysis on the effect of slip boundaries and radially applied exponential decaying/growing time-dependent pressure gradient on annular flow in curved concentric cylinders has been performed semi-analytically. In order to have an insight into the physical problem, a MATLAB program is written to determine and generate plots and numerical values for Dean velocity, skin frictions as well as Dean vortices. The flow is seen to be controlled by time \(\left( t \right)\), wall slip coefficient (\(\alpha , \beta )\) and the decaying/growing parameter of the pressure gradient \(\left( \delta \right)\). Our present computation has been carried out over a reasonable range of values with time taken over \(0.06 \le t \le 0.2\), decaying/growing parameter of pressure gradient over \(- 2.0 \le \delta \le 2.0\) and wall slip effect over \(0 \le \alpha ,\beta \le 2.0.\) Throughout our investigation, \(\delta > 0\) has been used to represent an exponentially decaying pressure gradient and is depicted as (a) while \(\delta < 0\) has been used to simulate a growing pressure gradient and denoted by (b) in Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15.

Figure 2 describes the influence of time and outer wall slip on Dean velocity. Increase in time is accompanied by an increase in Dean velocity for both decaying/growing exponential time-dependent pressure gradient. However, it is observed that the velocity profile is stronger accentuated for an exponentially growing time-dependent pressure gradient.

The combined effects of time, inner wall slip and exponentially decaying/growing time-dependent pressure gradient on Dean velocity are illustrated in Fig. 3. It is seen that along the inner wall, the effect of slippage is pronounced with a semi-parabolic profile. As expected, the role of time is to promote the flow for both components of exponential time-dependent pressure gradient.

Figure 4 shows the action of slip coefficient on both walls for an exponentially decaying/growing time-dependent pressure gradient as time passes. It is evident that higher Dean velocity profile is borne out of increased slip coefficient and time. In addition, the effect is subtle for an exponentially decaying time-dependent pressure gradient. This finding is the key in modelling and fabricating of real-time system transporting biofluids.

The outcome of varying inner and outer wall slip coefficient for a fixed value of time on Dean velocity is exhibited in Figs. 5 and 6. As shown in Fig. 5, the influence of enhancing inner wall slip coefficient is to increase the Dean velocity along the surface of the inner wall. A similar trend is observed in Fig. 6. However, the increase in this case is on the outer wall. In both Figs. 5 and 6, a growing pressure gradient supports a higher magnitude of Dean velocity. This behaviour is in line with the result reported by Jha and Yahaya [25].

The distribution of skin friction for variations of time along the inner wall when slip coefficient is applied on the outer wall and inner wall respectively for an exponentially decaying/growing time-dependent pressure gradient is illustrated in Figs. 7 and 8. Generally, it is found that the drag on the inner wall is minimum with a converging profile around the vicinity of the inner wall. However, as time passes a more distributed profile is seen along the outer wall. As expected, higher profiles are perceived with an exponentially growing pressure gradient.

Figure 9 shows the impact of dual wall slip coefficient on local skin friction for both components of exponential time-dependent pressure gradient and an increasing time. It is noted that the combined action of simultaneous slip condition on both walls and boosting time is to maximize the effect of shear stress on the inner wall of the cylinder.

On the other hand, the role of outer and inner wall slip condition on skin friction along the surface of the outer cylinder is depicted in Figs. 10 and 11. It is observed that as time increases, the shear stress also increases and the influence of the slip coefficient is obvious along the outer wall as viewed in Fig. 10. However, a slightly different attribute is noticed when the wall slip is applied on the inner cylinder as exhibited in Fig. 11. Here, the skin friction grows and attains its maximum midway and gradually diminishes with close proximity to the outer wall.

Figure 12 shows the impact of dual wall slip on skin friction along the outer wall for different values of time when the time-dependent pressure gradient is decaying/growing exponentially. It is obtained that skin friction along the outer wall is enhanced when time is increased.

The effect of varying time on Dean vortices with the application of outer and inner wall slip, respectively, is shown in Figs. 13 and 14. It is noted that the instability of the Dean vortices is felt stronger along the wall with no-slip boundary condition. Moreover, a decreasing time is the key in attaining stability of the Dean vortices.

Figure 15 presents the outcome of dual wall slip parameter and increasing time on Dean vortices for an exponentially decaying/growing time-dependent pressure gradient. It is noticed that the effect of the slip coefficient along both walls prompts a growth in the instability of the Dean vortices. Along the inner wall, a growing time increases the instability. However, a counter trend is seen with an increase in time along the outer wall. In addition, a higher magnitude of profile is seen with an exponentially growing time-dependent pressure gradient.

Conclusion

A mathematical model describing linear hydrodynamics stability of flow in curved annulus has been analysed semi-analytically. The mutual action of velocity slip and radially applied exponential decaying/growing time-dependent pressure gradient on the flow formation has also been investigated. Laplace transforms technique and a numerical-based approach known as Riemann-sum approximation (RSA) has been adopted in resolving the problem under consideration. The effect of controlling parameters governing the flow has been illustrated pictorially. The noteworthy observations are as follows:

-

i.

It is found that the velocity distribution increases substantially with a boost in time and slip wall coefficient.

-

ii.

Skin friction can be maximized by inducing an exponentially growing time-dependent pressure gradient, time and wall slip coefficient.

-

iii.

Instability of the Dean vortices can be minimized by applying an exponentially decaying time-dependent pressure gradient suppressing the effect of time.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- RSA:

-

Riemann-sum approximation

- \(r_{1}\) :

-

Radius of the inner cylinder (m)

- \(r_{2}\) :

-

Radius of the outer cylinder (m)

- \(P\) :

-

Static pressure (kg/ms2)

- \(R\) :

-

Dimensionless radius

- \(s\) :

-

Laplace parameter

- \(t\) :

-

Dimensionless time (s)

- \(U_{0}\) :

-

Reference velocity (m/s)

- \(u_{r^{\prime}}\) :

-

Radial velocity (m/s)

- \(u^{\prime}\) :

-

Circumferential velocity (m/s)

- \(U\) :

-

Dimensionless velocity

- \(\alpha\) :

-

Inner wall slip parameter

- \(\beta\) :

-

Outer wall slip parameter

- \(\delta\) :

-

Decaying/growing parameter of time-dependent pressure gradient

- \(\lambda\) :

-

Radii ratio (r2/r1)

- \(\rho\) :

-

Fluid density (kg/m3)

- \(\eta\) :

-

Dean vortices

- \(\tau\) :

-

Skin friction

- \(\upsilon\) :

-

Dynamic viscosity of the fluid (kg/m)

References

Dean, W.R.: Fluid motion in a curved channel . Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 121, 402–420 (1928)

Beavers, G.S., Joseph, D.D.: Boundary conditions at a naturally permeable wall. J. Fluid Mech. 30(1), 197–207 (1967)

Tretheway, D.C., Meinhart, C.D.: Apparent fluid slip at hydrophobic microchannel walls. Phys. Fluids 14(3), L9–L12 (2002)

Escudier, M., Oliveira, P., Pinho, F.: Fully developed laminar flow of purely viscous non-Newtonian liquids through annuli, including the effects of eccentricity and inner-cylinder rotation. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 23(1), 52–73 (2002)

Joseph, D., Ocando, D.: Slip velocity and lift. J. Fluid Mech. 454, 263–286 (2002)

Min, T., Kim, J.: Effects of hydrophobic surface on skin-friction drag. Phys. Fluids 16(7), L55–L58 (2004)

Choi, C.-H., Kim, C.-J.: Large slip of aqueous liquid flow over a nanoengineered superhydrophobic surface. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96(6), 066001 (2006)

Wang, C.Y.: Low Reynolds number slip flow in a curved rectangular duct. J. Appl. Mech. 69(2), 189–194 (2002)

Wang, C.Y.: Brief review of exact solutions for slip-flow in ducts and channels. J. Fluids Eng. 134(9), 094501 (2012)

Tsangaris, S.: Oscillatory flow of an incompressible, viscous-fluid in a straight annular pipe. J. Mec. Theor. Appl. 3(3), 467–478 (1984)

Tsangaris, S., Kondaxakis, D., Vlachakis, N.W.: Exact solution of the Navier-Stokes equations for the pulsating dean flow in a channel with porous walls. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 44(20), 1498–1509 (2006)

Tsangaris, S., Vlachakis, N.W.: Exact solution for the pulsating finite gap dean flow. Appl. Math. Model. 31(9), 1899–1906 (2007)

Chandratilleke, T.T., Nursubyakto, S.: Numerical prediction of secondary flow and convective heat transfer in externally heated curved rectangular ducts. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 42(2), 187–198 (2003)

Gupta, S., Poulikakos, D., Kurtcuoglu, V.: Analytical solution for pulsatile viscous flow in a straight elliptic annulus and application to the motion of the cerebrospinal fluid. Phys. Fluids 20(9), 1–12 (2008)

Zheng, L., Li, C., Zhang, X., Gao, Y.: Exact solutions for the unsteady rotating flows of a generalized Maxwell fluid with oscillating pressure gradient between coaxial cylinders. Comp. Math. Appl. 62(2), 1105–1115 (2011)

Nowruzi, H., Ghassemi, H., Yousefifard, M.: Prediction of hydrodynamic instability in the curved ducts by means of semi-analytical and ANN approaches. Part. Differ. Equ. Appl. Math. 1, 100004 (2020)

Avramenko, A.A., Tyrinov, A.I., Shevchuk, I.V., Dmitrenko, N.P.: Dean instability of nanofluids with radial temperature and concentration non-uniformity. Phys. Fluids 28(3), 034104 (2016)

Yen, J.T., Chang, C.C.: Magnetohydrodynamic channel flow under time-dependent pressure gradient. Phys. Fluids 4(11), 1355–1360 (1961)

Azad, M.A.K., Andallah, L.S.: Explicit exponential finite difference scheme for 1D Navier-Stokes Equation with time dependent pressure gradient. GANIT J. Bang. Math. Soc. 36, 79–90 (2016)

Mendiburu, A.A., Carrocci, L.R., Carvalho, J.A.: Analytical solutions for transient one-dimensional Couette flow considering constant and time-dependent pressure gradients. Eng. Térm. Therm. Eng. 8(2), 92–98 (2009)

Manos, T., Marinakis, G., Tsangaris, S.: Oscillating viscoelastic flow in a curved duct-exact analytical and numerical solution. J. Non-New. Fluid Mec. 135, 8–15 (2006)

Jafek, A., Feng, H., Broberg, D., Gale, B., Samuel, R., Aston, K., Jenkins, T.: Optimization of Dean flow microfluidic chip for sperm preparation for intrauterine insemination. Microfluid. Nanofluid. 24(60), 1–9 (2020)

Nikdoost, A., Rezai, P.: Dean flow velocity of viscoelastic fluids in curved microchannels. AIP Adv. 10, 1–7 (2020)

Gambo, D., Gambo, J.J.: Role of suction/injection and slip flow on hydromagnetic free convective flow in a vertical coaxial cylinder under the influence of radial magnetic field. Heat Transf. 25, 1–13 (2021)

Jha, B.K., Yahaya, J.D.: Unsteady Dean flow formation in an annulus with partial slippage: a Riemann-sum approximation approach. Results Eng. 5, 1–10 (2020)

Avramenko, A.A., Kuznetsov, A.V.: Instability of a slip flow in a curved channel formed by two concentric cylindrical surfaces. Eur. J. Mech. B/Fluids 28(6), 722–727 (2009)

Ramzan, M., Chung, J.D., Ullah, N.: Partial slip effect in the flow of MHD micropolar nanofluid flow due to a rotating disk—a numerical approach. Results Phys. 7, 3557–3566 (2017)

Jha, B.K., Yusuf, T.S.: Transient pressure driven flow in an annulus partially filled with porous material: Azimuthal pressure gradient. Math. Model. Eng. Probl. 5(3), 260–267 (2018)

Jha, B.K., Yahaya, J.D.: Transient Dean flow in an annulus: a semi-analytical approach. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 13(1), 169–176 (2018)

Jha, B.K., Yahaya, J.D.: Transient Dean flow in a channel with suction/injection: a semi-analytical approach. J. Proc. Mec. Eng. 233(5), 1–9 (2019)

Jha, B.K., Gambo, D.: Effect of an oscillating time-dependent pressure gradient on Dean flow: transient solution. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 9(39), 1–9 (2020)

Jha, B.K., Gambo, D.: Combined effects of suction/injection and exponentially decaying/growing time-dependent pressure gradient on unsteady Dean flow: a semi-analytical approach. GEM Int. J. Geomath. 11(28), 1–22 (2020)

Yusuf, T.S., Gambo, D.: Impact of heat generation/absorption on transient natural convective flow in an annulus filled with porous material subject to isothermal and adiabatic boundaries. GEM Int. J. Geomath. 10(20), 1–16 (2019)

Yusuf, T.S., Gambo, D.: Role of heat source/sink on time dependent free convective flow in a coaxial cylinder filled with porous material: a semi analytical approach. Int. J. Appl. Proc. Eng. IJAPE 256, 67–77 (2020)

Yusuf, T.S., Gambo, D., Olaife, A.H.: Effect of heat source/sink on MHD start-up natural convective flow in an annulus with isothermal and isoflux boundaries. Arab J. Basic Appl. Sci. 27(1), 364–373 (2020)

Khan, S.U., Al-Khaled, K., Bhatti, M.M.: Biconvection analysis for flow of Oldroyd-B nanofluid configured by a convectively heated surface with partial slip effectcs. Surf. Interfaces 23, 100982 (2021)

Zhang, L., Bhatti, M.M., Michaelides, E.E.: Electro-magnetohydrodynamic flow and heat transfer of a third-grade fluid using a Darcy-Brinkman-Forchheimer model. Int. J. Numer. Methods Heat Fluid Flow

Zaher, A.Z., Moawad, A.M.A., Mekheimer, Kh.S., Bhatti, M.M.: Residual time of sinusoidal metachronal ciliary flow of non-Newtonian fluid through ciliated walls: fertilization and implantation. Biomech. Model Mechanobiol.

Zhang, L., Bhatti, M.M., Marin, M., Mekheimer, Kh.S.: Entropy analysis on the blood flow through anisotropically tapered arteries filled with magnetic zinc-oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles. Entropy 22(10), 1070 (2020)

Pushpa, B.V., Sankar, M., Makinde, O.D.: Optimization of thermosolutal convection in vertical porous annulus with a circular baffle. Ther. Sci. Eng. Progress 20(2), 100735 (2020)

Makinde, O.D., Eegunjobi, A.S.: Entropy analysis of a variable viscosity MHD Couette flow between two concentric pipes with convective cooling. Eng. Trans. 68(4), 317–334 (2020)

Tzou, D.Y.: Macro to Microscale Heat Transfer: The Lagging Behavior. Taylor and Francis, London (1997)

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received in the course of this research work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BKJ performed the conceptualization, supervision and validation of the approaches in this research work. DG was responsible for the investigation, methodology, data curation, writing-original draft preparation, writing-reviewing and editing. All authors have read and approved final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Supplementary data.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jha, B.K., Gambo, D. Hydrodynamic effect of slip boundaries and exponentially decaying/growing time-dependent pressure gradient on Dean flow. J Egypt Math Soc 29, 11 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42787-021-00120-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42787-021-00120-z

Keywords

- Dean flow

- Exponential time-dependent pressure gradient

- Unsteady

- Riemann-sum approximation (RSA)

- Slip flow