Abstract

Let (G,∗) be a finite group and S={x∈G|x≠x−1} be a subset of G containing its non-self invertible elements. The inverse graph of G denoted by Γ(G) is a graph whose set of vertices coincides with G such that two distinct vertices x and y are adjacent if either x∗y∈S or y∗x∈S. In this paper, we study the energy of the dihedral and symmetric groups, we show that if G is a finite non-abelian group with exactly two non-self invertible elements, then the associated inverse graph Γ(G) is never a complete bipartite graph. Furthermore, we establish the isomorphism between the inverse graphs of a subgroup Dp of the dihedral group Dn of order 2p and subgroup Sk of the symmetric groups Sn of order k! such that \(2p = n!~(p,n,k \geq 3~\text {and}~p,n,k \in \mathbb {Z}^{+}).\)

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Graph representation is one of the combinatorial properties used to understand some interesting properties of complex structures. It is a known fact that the beauties of some algebraic structures in mathematics remain hidden, not until the associated Cayley graphs of these algebraic structures (semigroups, groups, rings, etc.), began to gain the attention of researchers. Recently, Alfuraidan and Zakariya [1] introduced and studied the inverse graphs associated with finite groups. They established some interesting graph-theoretic properties of the inverse graphs of some finite groups which further shed more light on the algebraic properties of the groups. They established the inter-relatedness between the algebraic properties of the finite groups and the graph-theoretic properties of the associated inverse graphs. The inverse graph was used to characterize some isomorphism problems of finite groups. In the same vein, Kalaimurugan and Megeshwaran [2] studied the magic labeling on the inverse graph. They considered a non-trivial abelian group A under addition and defined the Zk-magic labeling on inverse graphs from the finite cyclic group to be a graph G if there exists a labelling f:E(G)→A−{0} such that the vertex labelling f+(v) given as \(f^{+}(v) = \sum _{uv \in E(G)} f(uv)\) taken over all edges uv incident at v is a constant. They noted that the corresponding constant, say x, is the A-magic value of the associated inverse graph.

On the other hand, Jones and Lawson [3] studied graph inverse of semigroups, generalized the polycyclic inverse monoids and further showed how the graph inverse play an important role in the theory of C∗-algebras. Their work was targeted at two main goals: first, to provide an abstract characterization of graph inverse semi groups; and second, to show how this graph may be completed under suitable conditions, to form what they called the Cuntz-Krieger semigroup of the graph. According to [3], this semigroup is the ample semigroup of a topological groupoid associated with the graph, and the semigroup analog of the Leavitt path algebra of the graph. Mesyan and Mitchell [4] studied the semigroup-theoretic structure of G(E). Specifically, they described the non-Rees congruences on G(E) and showed that the quotient of G(E) by any Rees congruence is another graph inverse semigroup. They further classified the G(E) that have only Rees congruences and also found the minimum possible degree of a faithful representation by partial transformations of any countable G(E). Finally, they showed that a homomorphism of directed graphs can be extended to a homomorphism (that preserves zero) of the corresponding graph inverse semigroups if and only if it is injective. Very recently, Chalapathi and Kiran-Kumar [5] investigated some properties of invertible graphs of finite groups, invertible graphs were defined, and some interesting results were established using finite group classification. For each finite group, the size, girth, diameter, clique number, and the chromatic number were obtained. Furthermore, they showed that the invertible graphs are weakly perfect and specifically, formulas for enumerating the number of edges in the invertible graph of the symmetric group, and dihedral group were derived. They also established the relationships among isomorphic groups, non-isomorphic groups, and their respective invertible graphs.

The notion of energy of graphs was introduced by Gutman [6] in an attempt to study electron energy in theoretical chemistry. In brief, Gutman [7] studied and outlined the connection between the energy of graphs and the total electron energy of a class of organic molecules. He also obtained the relationship between the energy of graphs and their corresponding characteristics polynomials. Furthermore, Gutman [7] established some nice properties of graph extremals with their respective energies. Since then, energies of several types of graphs have been studied extensively in the literature. For instance, Andrade et al. [8] introduced and studied the lower bound for the energy of a symmetry matrix partitioned into blocks. According to [8], this bound is related to the spectrum of its quotient matrix. They gave the lower bound for the energy of a graph with a bridge and also presented some computational experiments in order to show some cases where lower bound is incomparable with the known lower bound of \(2\sqrt {m}\) (where m is the number of edges of the graph). Fadzil et al. [9] used a specific subset S={b,ab,...,an−bb} for the dihedral groups of order 2n, where n≥3 to find the Cayley graph with respect to the set. They computed the eigenvalues and the energies of the respective Cayley graphs and further generalized the energy of the generating subset of the dihedral groups.

Energy of graphs has vast applications in mathematics and other areas of science such as physics, chemistry, computer science, engineering, and biology, as well as in social science. For instance, combinatorial optimization can be studied using the energy of the graph of the adjacency matrix of an optimization problem. This helps to understand the partition problem of the associated adjacency matrix. Also, the energy of graph is applied to graph spectra in internet technologies, pattern recognition, and computer vision (see [10] for details). Since matrices are important structure in the field of complex networks, energy of graphs are considered in complex networks and social networks. In particular, networks that exhibit interesting topological characteristics. The concept of energy of graph is applied to egocentric network, which showed that the energy of the graph correlates to the vertex centrality measure (see [11] for details). In chemistry, energy of graph is applied to the theory of unsaturated conjugated hydrocarbons, known as the Huckel molecular orbital theory, while in physics, it is applied to a discrete model of membrane used to treat membrane vibration problem (see also [10] for details).

In this paper, motivated by the works of Alfuraidan and Zakariya [1], Gutman [7], and Fadzil et al. [9], we compute the energy of some inverse graphs which is the sum of the absolute values of the eigenvalues of adjacency matrices of their corresponding inverse graphs of finite groups. We study the energy of dihedral and symmetry groups and show that if G is a finite non-abelian group with exactly two non-self invertible elements, then the associated inverse graph Γ(G) is never a complete bipartite graph. Furthermore, we establish that the inverse graphs of the subgroup Dp of a dihedral group Dn of order 2p and the subgroup Sk of a symmetric groups Sn of order k! such that \(2p = n!~(p,n,k \geq 3~\text {and}~p,n,k \in \mathbb {Z}^{+})\) are isomorphic.

Preliminaries

We state some known and useful results which will be needed in the proofs of our main results and understanding of this paper. For the definitions of basic terms and results given in this section, see [1, 2, 4, 5, 9, 12, 21].

A graph Γ is an ordered triple (V(Γ),E(Γ),ΨΓ) consisting of a nonempty set of vertices V(Γ), a set E(Γ) of edges disjoint from V(Γ) and an incidence function ΨΓ that associates with each edge of Γ an unordered pair of (not necessarily distinct) vertices of Γ. If e∈E(Γ) and u,v∈V(Γ) such that ΨΓ(e) = uv, then e is said to join u and v; the vertices u and v are called the ends of e. The cardinality of V(Γ) and E(Γ) are called the order and size of Γ, respectively. The degree of a vertex u in a graph Γ denoted by δ(u) is the number of edges incident to it. A graph Γ is simple if it has no loops and no two of its links join the same pair of vertices. For the rest of this paper, our graph Γ is simple and undirected.

Definition 1

[5] Let (G,∗) be a finite group with the identity element e. Then, an element a∈G is called a self invertible element of G if a=a−1, where a−1 is the inverse of a in G. The set of all self invertible elements of G and its cardinality are denoted by S′ and |S′|, respectively.

Definition 2

[22, 23] Let N be a positive integer, a complete graph is a graph with N vertices and an edge between every two vertices. That is every vertex is adjacent to every other vertex. Consequently, if a graph contains at least one non-adjacent pair of vertices, then that graph is not complete. A complete graph is usually denoted by KN.

Definition 3

[1] Let (G,∗) be a finite group and S={x∈G|x≠x−1} be a subset of G. The inverse graph Γ(G) associated with G is the graph whose set of vertices coincides with G such that two distinct vertices x and y are adjacent if and only if either x∗y∈S or y∗x∈S.

Remark 1

[1] Clearly, the identity e is a trivial self-invertible element in a finite group G. Hence, e∉S. Consequently, the order of S is obviously less than the order of G. To be specific, if G contains no self-invertible element besides the identity then ∣S∣=∣G∣−1

Example 1

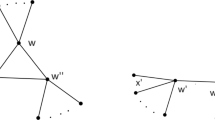

[1] The graphs in Figs. 1 and 2 are the inverse graphs of the groups \((\mathbb {Z}_{3},+)\), S={1,2} and \((\mathbb {Z}_{5} \setminus \{0\},\ast)\), S={2,3} under the usual addition and multiplication, respectively.

Definition 4

[15] A bipartite graph is a graph with its set of vertices decomposed into two disjoint sets such that no two graph vertices within the same set are adjacent.

Theorem 1

[1] Let G be a finite abelian group with exactly two non-self invertible elements. Then, the associated inverse graph Γ(G) is complete bipartite.

Theorem 2

[12] Let Γ be a graph, the energy of Γ is never an odd integer.

Theorem 3

[13] Let ai and bi be two vectors in \(\mathbb {R}^{n}\). The Cauchy-Schwartz inequality states that

Definition 5

[16] The dihedral group Dn is the group of symmetries of a regular polygon with n vertices. This polygon is seen as having vertices on the unit circle, with vertices labeled 0, 1,..., n−1 starting at (1,0) and proceeding counterclockwise at angles in multiples of 360/n degrees (that is, 2 π/n radians). There are two types of symmetries of the n-gon, each one gives rise to n elements in the group Dn.

-

Rotations R0,R1,...,Rn−1, where Rk is rotation of angle 2πk/n where k={0,1,...,n−1}.

-

Reflections S0,S1,...,Sn−1, where Sk is a reflection about the line through the origin and making an angle of πk/n with the horizontal axis.

The group operation is given by the composition of symmetries: if a and b are two elements in Dn, that is to say, a∗b is the symmetry obtained by applying first a, followed by b. It is obvious that the following relations hold in Dn:

where 0≤i,j≤n−1, and both i+j and i−j are computed modulo n. It can be observed that R0 is the identity, \(R^{-1}_{i} = R_{n-i}\), and \(S^{-1}_{i} = S_{i}\).

Theorem 4

[17] Let G=Sn be a finite group of order n, the adjacency spectrum of Sn = \(\{\sqrt {n-1}, 0,..., 0,-\sqrt {n-1}\); where eigenvalue λ=0 has multiplicity (n−2).

Definition 6

[18] Let Γbe a graph with n vertices and m edges, A=[ai,j] be the adjacency matrix for Γ and λ1,λ2,...,λn be the eigenvalues of A. The energy of graph Γ is defined as the sum of the absolute values of the eigenvalues of A. That is,

Definition 7

[17] Adjacency spectrum of a graph is the set of all n eigenvalues of the (n×n) adjacency matrix is denoted as {λ1,λ2,⋯,λn} where λi≥λj for ∀ i<j.

Main results

This section introduces the energy of the inverse graph of both the dihedral and symmetric groups. We begin with the following example of a dihedral group.

Example 2

Let Dn be the dihedral group of equilateral triangle, with vertices on the unit circle, at angles 0, 2π∖3, and 4π∖3. The matrix representation according to [16] is given by

and D3={R0,R1,R2,S0,S1,S2}. By Definition 5, we obtain the compositions of rotations and reflections of the equilateral triangle in the following table;

Also, from Definition 3 and to ease understanding, we rewrite the elements of D3 = {1,2,3,4,5,6} (where R0=1,R1=2,R2=3,S0=4,S1=5 and S2=6) and S={x∈D3|x≠x−1} = {2,3}. Then, the associated inverse graph of D3 are the two disjointed graphs in the figure below.

From Fig. 3, we can draw the adjacency matrix of Γ(D3) as follows:

To compute the eigenvalues of A, we compute the roots of the characteristics polynomial of A which is given as λ6−5λ4+6λ2−2λ3+4λ. The roots λi (i=1,2,...,6) of the polynomial is given as 0, 0, –1, 2, –\(\sqrt {2}\), and \(\sqrt {2}\). Hence, from Definition 6, the energy of the inverse graph of D3 is \(3+2\sqrt {2}\).

Theorem 5

Let G=Dn be the dihedral group of order 2n, where n≥3 and S={x∈G|x≠x−1} be a subset of Dn. Then, the energy \(\bar {E}\) of the inverse graph Γ(G) is given as \(3 + 2\sqrt {2} \leq \bar {E}(\Gamma (G)) < 2m \) where m is the number of edges in Γ(G).

Proof

Let G=Dn be the dihedral group of order 2n, where n≥3 and S={x∈G|x≠x−1}. Suppose Γ(G) is the inverse graph of the dihedral group with n vertices and m edges. Let A be the adjacency matrix of Γ with λ1,λ2,⋯,λn as its eigenvalues. Then, to obtain the bounds of the energy of our inverse graphs, we shall adopt the general form of energy of graphs (see Brualdi [20]) given as

Recall that, the inverse graph Γ of finite groups are simple graphs. Furthermore, they have no loops, and thus, the leading diagonals of the adjacency matrix A are 0s; therefore, the determinant of A; det(A)=0 then (1) becomes

Also, the energy of a graph is a function of both the vertex set and the edge set (see [20]). Therefore, \( \bar {E}(\Gamma (G)) \in \mathbb {R}^{+} \). And if (2) holds, then it is safe to write the following

And using the inequality property (if a≤b<c, then a<c) and we can write (3) as

Furthermore, since the least number n of Dn is 3, the lower bound is obvious from Example 2. Then, it is safe to write

(see Example 2), then combining (4) and (5), we can conclude that

□

Theorem 6

[19] Let G be a finite non-abelian group generated by two elements of order 2.Then, G is isomorphic to a dihedral group.

Theorem 7

Let G=Dn be the dihedral group of order 2n, where n≥3 and S={x∈G|x≠x−1} be a subset of Dn. Then, the inverse graph Γ(Dn) is never a complete bipartite graph.

Proof

Let G=Dn be the dihedral group of order 2n, where n≥3, S={x∈G|x≠x−1} and S⊆Dn. Suppose the inverse graph of Dn is bipartite for all n≥3, then the set of vertices V(Γ(Dn)) can be partitioned into two sets, say V1 and V2 (the set of rotation of angle 2πk/n and the set of reflections about the line through the origin) and also, there exist two vertices u∈V1 and v∈V2 which are adjacent. But the dihedral groups are non-abelian and these disjoint partitions contain elements which are not commutative. Hence, by Definition 3, it is not possible for a v∈V1 and a u∈V2 to be adjacent. □

Corollary 1

Let G be a finite non-abelian group with exactly two non-self invertible elements. Then, the associated inverse graph Γ(G) is never a complete bipartite graph.

Proof

Let G be a finite non-abelian group with ∣S∣ = 2 and let the partition of the vertex set V(Γ(G))={V1,V2}, where V1={x∣x∈S} and V2={y∣y∉S}. Suppose x,y∈V(Γ(G)) and for the pair x,y to be adjacent, x∗y will be an element in S But G is non-abelian and S contains only two elements. Then, obviously there is no any other element say z such that z=x∗y∈V1. □

Remark 2

Let G=Dn be the dihedral group of order 2n with a non bipartite graph, then the adjacency matrix of G is non-symmetric and the sum of the absolute value of the eigenvalues is not equal to zero.

Corollary 2

Let G be a finite non-abelian group with an even order n and S={x∈G|x≠x−1}. Then, the associated inverse graph Γ(G) of the group decomposes into two smaller disjoint subgraphs.

Proof

Let G be a non-abelian group of order n where n is even, S={x∈G|x≠x−1}. Suppose V1 and V2 are two disjoint vertex sets of G, where \(V_{1}(\Gamma (G)) = \{1, 2,..., \frac {n}{2}\}\), \(V_{2}(\Gamma (G)) = \{\frac {n}{2},..., n\}\). Note that, for x,y∈G to be adjacent, then x∗y or y∗x must be in S. However, G is non-abelian and obviously, not all x and y in G are commutative. To clearly show that there are two distinct vertex sets which are disjoint but forms the disjoint subgraphs, we will consider two cases.

Case (I), let x and y be two vertices in G, such that x∗y and y∗x are both in S, they might not necessarily be the same, but their is a common edge between x and y. This sets of vertices and edges form a part of the inverse graph Γ(G) that is connected.

Case (II), let x and y be two different vertices in G such that x∗y is in S but the converse y∗x is not in S, this set of vertices also form the second part of the inverse graph Γ(G) which is not connected. Thus, clearly, we can conclude that an inverse graph Γ(G) of a non-abelian group G with an even order n decomposes into two smaller disjoint subgraphs. □

Example 3

Let

be the symmetric group of order 6. By Definition 3, we obtain that

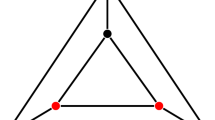

Since S={x∈G|x≠x−1}, then the inverse graph Γ(S3) of S3 is (Fig. 4)

Theorem 8

Let Dp⊆Dn be a subgroup of the dihedral group of order 2p and Sk⊆Sn be a subgroup of the symmetric group of order k!; k,p≥3 are positive integers which are not necessarily equal but 2p=k! and S={x∈Dp,Sk|x≠x−1}. Then, the inverse graphs of Dp and Sk are isomorphic.

Proof

Let Dp⊆Dn be a subgroup of a dihedral group of order 2p and Sk⊆Sn be a subgroup of a symmetric group of order k!; k,p≥3 are positive integers which are not necessarily equal. Suppose 2p=k! and S={x∈Dp and Sk|x≠x−1}, it suffices to show that the inverse graphs of Γ(Dp) and Γ(Sk) are isomorphic then the finite groups Dp and Sk have the same adjacency matrix. If the order of ∣S∣=2 then by Theorem 6, it is obvious that Dp and Sk have the same adjacency matrix, but if ∣S∣≠2, then ∣S∣ = 1 or ∣S∣>2. If ∣S∣ = 1, then the relation Γ(Dp)≃Γ(Sk) is trivial and we are left to show for when ∣S∣≥3. Suppose we claim that Γ(Dp)≃Γ(Sk) when ∣S∣≥3, then we have to show a map ψ which is isomorphic on the two groups, we first show that ψ is an injection. So let x and y be two elements of Dp and let a and b be two corresponding vertices of Γ(Dp) if a and b are equal they must have the same effect on Γ(Sk). Check their effect on the identity vertex, a=a(e)=ψ(e)=b(e)=b clearly ψ(a)=ψ(b) shows the injection of the map ψ and a = b and the bijection is obvious. □

Consequently, we obtain the following remark from Theorems 5 and 8.

Remark 3

Let Sk be a subgroup of the symmetric group Sn (Sk⊆Sn), such that the inverse graph of Sk; Γ(Sk)≃Γ(Dn), where Dp is a subgroup of Dn and \(k,\ p,\ n\in \mathbb {Z}\). Then, the energies \(\bar {E}(\Gamma (S_{k}))\) and \(\bar {E}(\Gamma (D_{p}))\) are equal.

Conclusions

This study has highlighted the energies of the dihedral and symmetric groups; clearly, we show that the energies of these groups are in this range \(3 + 2\sqrt {2}\leq \bar {E}(\Gamma (G)) < 2m\), though these energies might not necessarily be the same, because from Theorem 4 and Definition 7, this assertion is obvious. However, if we consider the energies of the subgroups Dp and Sk of the dihedral and symmetric groups such that 2p = n!, the energies are necessarily the same. Furthermore, the associated inverse graphs of the group Dp⊆Dn, with order 2p and Sk⊆Sn, with order k!) are isomorphic if 2p = n!. Further research is encouraged to find the energy of inverse graphs of finite groups in general.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no data sets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Alfuraidan, M. R., Zakariya, Y. F.: Inverse graphs associated with finite groups. Electron. J. Graph Theory Appl. 5(2), 142–154 (2017).

Kalaimurugan, G., Megeshwaran, K.: The Zk-magic labeling on inverse graphs from finite cyclic group. Am. Int. J. Res. Sci. Technol. Eng. Math. 23(1), 199–201 (2018).

Jones, D. G., Lawson, M. V.: Graph inverse semigroups: their characterization and completion. J. Alg. 409, 444–473 (2014).

Mesyan, Z., Mitchell, J. D.: The structure of a graph inverse semigroup (2015). https://academics.uccs.edu/zmesyan/papers/GraphSemigroups. Accessed 20 Nov 2019.

Chalapathi, T., Kiran-Kumar, R. V. M. S. S.: Invertible graphs of finite groups. Comput. Sci. J. Moldova. 26(2), 77 (2018).

Gutman, I: The energy of a graph. Ber. Math. Statist. Sekt. Forschungsz. Graz. 103, 1–22 (1978).

Gutman, I: The energy of a graph: old and new results. Algebraic Comb. Appl., 196–211 (2001). Springer, Berlin.

Andrade, E, Robbiano, M, Martin, B. S: A lower bound for the energy of symmetry matrices and graphs. Linear Algebra Appl. 513, 264–275 (2017).

Fadzil, A. F. A, Sarmin, N. H, Erfanian, A: The energy of Cayley graphs for generating subset of the Dihedral Groups. Matematika:MJIAM. 35(3), 371–376 (2019).

Cvetkovi’c, D. M, Doob, M, Sachs, H: Spectra of graphs: theory and application. Academic Pr. 87, 252–258 (1980).

Morzy, M., Kajdanowicz, T.: Graph energies of egocentric networks and their correlation with vertex centrality measures. Entropy. arXiv:1809.00094v2 (2018).

Bapat, R. B., Pati, S.: Energy of a graph is never an Odd Integer (2004). https://Citeseerx.ist.psu.edu. Accessed 14 Dec 2019.

Wigren, T.: The Cauchy-Schwartz inequality, proofs and application in various spaces (2015). https://www.diva-portal.se. Accessed 10 June 2020.

Gupta, A.: Discrete Mathematics. S.K. Kataria & Sons, Delhi (2008).

Hoffman, A. J.: On the line graph of the complete bipartite graph (1964). https://projecteuclid.org/euclid.aoms. Accessed 3 Dec 2019.

Suciu, A.: Group theory : the dihedral groups (2010). www.math.neu.edu/suciu/MATH3175/ugroup.fa10.html. Accessed 14 Mar 2020.

Jones, O.: Spectra of simple graphs. Whitman College, Walla-Walla (2013).

Koolen, J., Moulton, V.: Maximal energy graphs. Adv. Appl. Math. 26, 47–52 (2001).

Conrad, K.: Dihedral group II (2009). http://www.math.uconn.edu/kconrad/blurbs/grouptheory/dihedral2.pdf. Accessed 14 Mar 2020.

Brualdi, R. A.: Energy of a graph. AIM Work, Sydney (2006).

Bondy, J. A., Murty, U. S. R.: Graph theory with application, vol. 1. Elsevier Science Publishing Co., Inc., Cambridge (1976).

Martins, J. L.: Complete graphs (2010). http://jlmartins.faculty.ku.edu. Accessed 14 Nov 2019.

Butler, S.: Graph theory (2015). http://www3.nd.edu/CGT-early. Accessed 14 Nov 2019.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the anonymous referees for their careful reading, constructive comments, and fruitful suggestions that substantially improved the manuscript.

Funding

The authors wish to sincerely thank the Egyptian Mathematical Society for shouldering the cost of publishing this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OE conceived the study, wrote the results, and proofs, KOA validated the results and help in proofreading the manuscript and AA helped with the literature review. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ejima, O., AREMU, K.O. & Audu, A. Energy of inverse graphs of dihedral and symmetric groups. J Egypt Math Soc 28, 43 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42787-020-00101-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42787-020-00101-8