Abstract

Background

The knee osteoarthritis (OA) is a joint disease characterized by degradation of articular cartilage that leads to chronic inflammation. Exercise programs and photobiomodulation (PBM) are capable of modulating the inflammatory process of minimizing functional disability related to knee OA. However, their association on the concentration of biomarkers related to OA development has not been studied yet. The aim of the present study is to investigate the effects of PBM (via cluster) with a physical exercise program in functional capacity, serum inflammatory and cartilage degradation biomarkers in patients with knee OA.

Methods

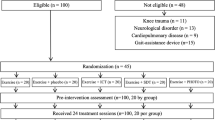

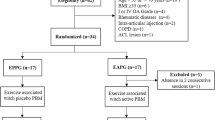

Forty-two patients were randomly allocated in 3 groups: ESP: exercise + sham PBM; EAP: exercise + PBM and CG: control group. Six patients were excluded before finished the experimental period. The analyzed outcomes in baseline and 8-week were: the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis (WOMAC) and the evaluation of serum biomarkers concentration (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10 e TNF-α, and CTX-II).

Results

An increase in the functional capacity was observed in the WOMAC total score for both treated groups (p < 0.001) and ESP presents a lower value compared to CG (p < 0.05) the 8-week post-treatment. In addition, there was a significant increase in IL-10 concentration of EAP (p < 0.05) and higher value compared to CG (p < 0.001) the 8-week post-treatment. Moreover, an increase in IL-1β concentration was observed for CG (p < 0.05). No other difference was observed comparing the other groups.

Conclusion

Our data suggest that the physical exercise therapy could be a strategy for increasing functional capacity and in association with PBM for increasing IL-10 levels in OA knee individuals.

Trial registration: ReBEC (RBR-7t6nzr).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) leads to degradation of articular cartilage, formation of osteophytes, decrease of joint space and degeneration of subchondral bone and is characterized as a chronic joint disease [1]. These morphological alterations culminate in an increasing of the level of articular pain, loss of function, decrease in the range of motion and muscle weakness, impairing the quality of life of the patients [2].

The pathogenesis of OA has relation with the increase of expression of specific cytokines and immune system and, which contribute to cartilage degradation [3, 4]. It has been demonstrated that patients with OA showed high levels of proinflammatory cytokines, which disturb the catabolism and anabolism processes, being responsible by inflammation and consequence articular cartilage degeneration [5]. In this context, the most important cytokines involved in this process are Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and interleukin -6 (IL-6) [6]. As result of degradation of cartilage, a release of protein specific tissue fragments (neo-epitopes) in cleavage of type II collagen by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) can be observe, especially with analyze of biomarker as C-telopeptide of type II collagen (CTX-II) [7]. Based on this, the inhibition of interleukins (ILs) activity and analysis of CTX-II as a biomarker of progression of cartilage lesion are related to radiological grades of cartilage degradation and may help to improved strategies to treat OA [8].

In this context, for OA, one of the most common treatments is based on pharmacological intervention, mainly nonsteroidal and steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) [9]. However, the continuous use of NSAIDs can lead to severe adverse effects, like gastrointestinal problems, and limited efficacy [10]. In an attempt to attenuate these problems, alternative treatments have been studied including physical exercise programs, presenting positive effects on pain control, joint dysfunction and disability in patients with OA [11]. Furthermore, Castrogiovanni et al. [12] demonstrated that the moderate physical activity (MPA) significantly increased on the expression of anti-inflammatory [interleukin-4 (IL-4) and interleukin-10 (IL-10)] biomarkers in the synovium of an OA-induced rat model. The exercise protocol has been shown to have an anti-inflammatory effect, reducing levels of biomarkers like IL-6 and TNFα and suggesting that cytokine reduction can be an effective contribution for modulating pain due to OA [13].

Another promising therapeutic intervention that has been showing positive effects on degradation of cartilage tissue in the presence of OA is the low-level laser therapy (LLLT) or more recently, photobiomodulation (PBM) [14, 15]. It is well known that PBM produces stimulatory effect on healing and has the ability of modulating the inflammatory process in different tissues, including cartilage [5, 16]. Chondroprotective effects, inhibition of cartilage degradation, decreases in the expression of chemotactic factors and inflammatory cytokines and increase antioxidant enzyme levels have been observed in several experimental model of OA in rats after PBM [17, 18]. Also, clinical trials have demonstrated that PBM is able of reducing pain, articular stiffness, knee swelling, increasing the functional performance in knee OA patients [10, 19]. Alghadir, et al. [20] showed that PBM (850 nm, 50mW, 6 J/point), applied in eight points on knee during 4 weeks/ two times per week, improved the functional capacity evaluated by Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) in patients with knee OA (grade II or III).

Furthermore, some authors have been investigating the association of physical exercise and PBM on the management of OA symptoms [21, 22]. De Paula Gomes et al. [21] observed that PBM nine diode cluster device (one 905 nm super-pulsed diode laser with, four 875 nm light-emitting diode (LED) and four 640 nm LED) associated to a physical exercise program had positive effects on reducing pain intensity in individuals with knee OA. Similar findings were observed by Alayat et al., [23] and de Matos Brunelli Braghin et al., [24].

Although all the positive effects of physical exercise programs for treatment of OA, its association with PBM via a cluster device on the expression of ILs and biomarkers related to cartilage degradation in patients with OA has not been studied yet. In this context, based on the need of determining a more appropriate therapeutic intervention to treat patients with OA, the present study aimed to investigate the effects of the incorporation of PBM (via cluster) into a physical exercise program in serum inflammatory biomarkers (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10 e TNF-α), cartilage degradation biomarker (CTX-II) and functional capacity (WOMAC) in patients with knee OA.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

This is a single-blind (participants) randomized controlled trial. Ethical approval (Ethics in Human Research Committee of the Federal University of São Paulo- approval number 1.368.478) and written informed consent (patients signed) were obtained. The study was conducted at the Laboratory of Manual and Physical Resources and Balance Space – Fitness and Health from April 2018 to February 2020 and was logged with the Brazilian Clinical Trials Registry (RBR-7t6nzr). All participants were recruited via advertisements in local newspapers and social media.

Patients

As eligibility criteria, patients had aged between 55 and 70 years, present symptomatic OA in the previous 6 months, a diagnosis of unilateral or bilateral knee OA according to the American College of Rheumatology and a radiographic confirmation of OA (grades 2 or 3 of the Kellgren-Lawrence classification) [25]. The diagnosis of knee OA was determined through an examination and the written opinion of a specialist in rheumatic diseases. Also, patients should present BMI between 22 to 35 kg/m2, criteria established by Pan American Health Organization [26], more than 2 points on the Numeric Rating Pain Scale and should be classified as active and irregularly active (physical activity with a frequency of at least 3 times a week or a minimum of 150 min per week, according to Criteria established by American College of Sports Medicine measures by the International Physical Activity Questionnaire – Short Version (IPAQ).

Patients were excluded if they have: fibromyalgia and/or any kind of orthopedic or rheumatic diseases that may prevent the physical exercise; surgery of the knee within the past 6 months or joint replacement. Also, patients with diagnoses of lung diseases, cardiologic alterations, uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes and had any contraindications to PBM as cancer. During the study, patients who missed two consecutive training sessions or more than 3 sessions along the treatment and who discontinued the pharmacological treatment for OA started before the study were excluded.

Randomization

All patients met all inclusion criteria to participate in the study and signed a consent form. 42 patients were randomly allocated in ESP, EAP or CG groups, as observed below:

-

ESP: exercise + sham PBM, patients of this group performed the physical exercise program associated to PBM sham irradiation;

-

EAP: exercise + active PBM, patients of this group performed the physical exercise program associated to active PBM irradiation.

-

CG: control group, patients of this group were not submitted to any kind of therapeutical intervention.

A researcher, who was not involved in the experiment, conducted the randomization process by a simple drawing through a computer program that created a random table of numbers and put these numbers (1, 2 and 3) on opaque envelopes corresponding the group (ESP, EAP and CG), respectively.

Evaluation and reevaluation were performed by a researcher blinded to the experimental groups. Patients were also blinded to the mode of PBM application (sham or active).

Sample size

The sample size calculation was performed using the GPower 3.0.10 program with parameters: effects size of 0.25 [27], power observed of 0.75 and α = 5%, considering ANOVA model for three groups. The required sample would be 12 patients for each treatment group ESP, EAP or CG with a total of 36 patients. Each treatment group was started with 14 patients for possible dropout.

Experimental procedures

After the initial evaluation, the following experimental procedures were made 48 h before and 48 h after interventions: blood collection and functional capacity analysis (WOMAC). Participants of the control group were oriented to maintain the same habits and do not start any new treatment for the period of 8 weeks.

Assessments

WOMAC questionnaire

The functional capacity of lower limb and knee joint could be evaluated by using Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis (WOMAC). The WOMAC is a self-administered reliable and valid questionnaire for patients with hip and knee OA and used for assessment of pain, stiffness joints, and physical activity of patients with hip and knee OA [28, 29]. The total score range of 0–96 and increased scores indicate a higher level of disability and lower level of quality of life.

Blood collection and serum biomarkers measurement

One biomedical collected 8 ml of peripheral blood samples from each patient before and after intervention period. After collected, the samples were centrifuged to prepare the plasma and stored at -80 °C in cryogenic tubes until in measurement. All the samples were sent to a certificate laboratory for analyses. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) kits were used to analyze the levels of CTX-II (MyBioSource), IL-1β and IL-10 (Enzo Life Sciences, Inc.) and IL-6, IL-8 e TNF-α (Fine Test®) following the procedures recommended by the manufacturer with automated pipetting.

Interventions

Both groups, ESP and EAP, received the intervention excepted CG (waitlist).

Physical exercise program

The physical exercise protocol used was adapted from the study by Silva et al. [30] and Foley et al., [31]. A protocol with warming (5 min on treadmill), 6 strength exercises (Hip abductors and adductors chair, SLR – seated leg raise, Glute Bridge (Hip lift), Knee flexors and extensors chair) and stretching of major muscle groups was used for this purpose. The patients were subjected to a physical exercise protocol twice a week (Monday and Wednesday) for 8 consecutive weeks performed individually and supervised by a physical therapist. The application of the physical exercise protocol occurred according to 1-RM (repetition maximum) was determined each 2 weeks for prescription and load progression of the exercises. The exercise consisted 3 sets of 8 repetitions each, with 60% of 1-RM and a rest interval of 2–3 min between sets based on American Geriatrics Society [32] for patients with OA.

PBM via cluster

A cluster with 7 diodes and an infrared wavelength (808 nm) was used in continuous mode, a 0.05cm2 spot size, 100mW power output, 2 W/cm2 power density, 91 J/cm2 energy density, and energy of 4 J per point/ 56 J per knee, 40 s per application based on recommendations of the World Association of Laser Therapy [33]. The cluster dimension is 150 mm(L) × 100 mm(W) × 55 mm(H), with 1 cm of distance between infrared diodes. After each training session for ESP and EAP, respectively, sham or active PBM was applied on medial and lateral region of knee affected for unilateral OA and applied on medial and lateral region of most affected knee for bilateral OA (with knee positioned at 45 degrees of flexion) (Fig. 1). A researcher responsible to conduct the intervention turned on the device of PBM irradiation and immediately turned off the equipment to apply the sham PBM.

Statistical analysis

To analyze the variables age, height, body mass, BMI, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α, CTX-II and WOMAC at groups and evaluations, were performed the analysis of variance (ANOVA one-way and two-way test) followed by Fisher’s post hoc test to identify the possible differences among groups. The adopted significant value was α < 5%. Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The difference between groups was performed per-protocol analysis.

Results

Six patients (one from ESP, one from EAP and four from CG) were excluded from the study due to the absence in 2 consecutive treatment sessions. Table 1 displays the baseline values of the outcome measures, anthropometric and demographic characteristics of the participants per group. Significant difference among ESP (p = 0.024), EAP (p = 0.009) and CG were identified for age. The EAP group showed higher values of BMI compared to CG (p = 0.04). The percentage of the weight range for each group was 15.4% normal weight, 69.2% overweight and 15.4% obesity for ESP; 30.8% normal weigh, 38.4% overweight and 30.8% obesity for EAP and 50% normal weigh, 40% overweight and 10% obesity for CG.

Figure 2 shows the baseline and 8-week values of WOMAC total score. The results demonstrated that there was significant difference between ESP, in the baseline compared to ESP in the 8-week (p = 0.00006), between EAP in the baseline and EAP in the 8-week (p = 0.00002) and between ESP and CG in the 8-week (p = 0.011).

Values of WOMAC in the baseline and in the 8-week for all the experimental groups. WOMAC: Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index; ESP: exercise and sham PBM group; EAP: exercise and active PBM group; CG: control group. *statistical significance between in the baseline and in the 8-week. aStatistical significance from ESP group in the same condition

The results of WOMAC pain, stiffness and function subscales are demonstrated in Table 2. There was significant decrease in all domains for ESP and EAP compared baseline with 8-week evaluation (p < 0,05) and significant decrease in WOMAC stiffness subscale for CG (p = 0.01). Thus, in baseline values, significant difference was found between the EAP and ESP in WOMAC pain (p = 0.04) and function (p = 0,0001) subscales, and between EAP and CG in WOMAC function subscale (p = 0.02). Significant difference was found between the ESP and CG in WOMAC pain (p = 0.02) and function (p = 0.01) subscales 8-week.

Figure 3 shows the baseline and 8-week values of the IL-10. It is possible to observe a statistical significant difference between the values found for EAP in the baseline compared to the 8-week (p = 0.047). Also, a significant difference was found between the values of EAP and CG after the experimental period (p = 0.0009).

Values of IL-10 concentration in the baseline and in the 8-week for all the experimental groups. IL-10: interleukin-10; ESP: exercise and sham PBM group; EAP: exercise and active PBM group; CG: control group. *statistical significance between in the baseline and 8-week values. &statistical significance between in the 8-week values

For IL-1β expression, there was a significant increase and difference between the values found in the baseline and in the 8-week for CG (p = 0.016) (Fig. 4).

Table 3 shows the values found in the baseline and in the 8-week of the pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α) and cartilage degradation biomarkers (CTX-II). For these variables, no significant difference was observed.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrated that the physical exercise program was able of increasing the functional capacity in the patients and, the associated treatments increased IL-10 expression compared to CG after the experimental period. In addition, IL-1β expression was higher for CG comparing the values in the baseline and 8-week and no difference for the others biomarkers were observed.

Knee OA is clinically associated with pain and loss of functional capacity, reaching 25% of the population over the age of 60 years [34]. As described above, the lower WOMAC score demonstrated by the physical exercised patients (irradiated or not with PBM) is possibly related to the increase in muscle strength after the exercise program, improving the joint stability and the level of pain, and consequently, leading to the improvement of the functional capacity. Interestingly, PBM did not produce any extra positive effect in the exercised patients. Data from the literature do not corroborate the findings of the present study demonstrating a superior effect measured by WOMAC in exercised and irradiated patients with OA [35,36,37]. Kheshie et al. [36] also observed a decrease in WOMAC subscales in patients with OA treated with physical exercises and PBM. One hypothesis that can be raised is that the PBM parameters used in this study were not sufficient to produce an additional effect in the exercised patients.

Furthermore, it is well known that IL-10 has an important anti-inflammatory role in OA, presenting a chondroprotective effect and, inhibiting chondrocyte apoptosis [38]. Our results showed that the active PBM associated with physical exercises significantly increased IL-10 expression after the experimental period of treatment. Assis et al., [17] also observed an increase of IL-10 expression in an experimental study, submitting rats with OA to a program of aerobic exercises and PBM irradiation. All the positive effects may be related to the effects of physical exercises and PBM on inflammatory markers. Physical exercises (and the related muscle contraction) produce a mechanotransduction stimulus, which maintain homeostasis of articular cartilage and contribute to attenuate OA physiological events [39]. As a consequence, physical exercise programs have anabolic, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects in OA patients [40]. Moreover, many studies have demonstrated the anti-inflammatory effects of PBM [41, 42]. PBM is able to modulate mRNA gene expression of IL-10 in acute and chronic inflammatory phase and decreases the expression of this cytokine and consequently modulates the inflammatory process of OA [43]. Taking together, the combined treatments presented a positive effect on IL-10 expression, which could represent a modulation of the inflammatory process.

IL-1β is considered one of the main cytokines in OA development and the literature points out that the reduction of IL-1β production is an indication of the attenuation of cartilage degenerative process related to OA [44]. CG demonstrated a significant increase of IL-1β expression after the experimental period. Similarly, an experimental study using rats with OA also observed a higher IL-1β expression in the control animals compared to the treated ones CG [45]. In this context, it can be suggested that the treatments were able to positively kept stable the IL-1β expression.

IL-6, a pro-inflammatory cytokine has a catabolic activity in the pathogenesis of OA. In the present study, no significant difference in IL-6 expression was observed in both experimental periods for any group. Conversely, Aguiar et al., [13] found a significant reduction in IL-6 levels in patients with knee OA, after a treatment of flexibility training and muscle strengthening, 3 times a week for 12 weeks. Furthermore, a systematic review concluded that PBM has no effect on the expression of the inflammatory cytokine IL-6 in OA animals [46]. However, experimental studies indicate that PBM is capable of modulating inflammatory mediators such as IL-6 in rats using an experimental model of joint inflammation [47]. The controversial results may be related to PBM parameters or the frequency if the treatment.

Furthermore, both treatments did not have any effect on IL-8 and TNF-α cytokines concentration. IL-8 is a chemokine produced by various inflammatory cells such as neutrophils, basophils, macrophages and T cells [48]. TNF-α, a pro-inflammatory cytokine seems to be related to IL-1β (pro-inflammatory cytokine) because are secreted by the same cells of the joint, in addition the increased presence of TNF-α stimulates the synthesis of IL-6 and IL-8 [49]. These results corroborates with Helmark et al., [50] who also observed that a resistance exercise training (25 sets of 10 repetitions at 60% of 1-RM) have not decreased the levels of IL-8 and IL-6 of patients with knee OA. Aguiar et al., [13] have not observed changes in TNF-α expression after 12 weeks of physical training using 60–80% of the maximum load of individuals with knee OA. In addition, a study applied PBM immediately after total knee arthroplasty and observed a decrease of IL-8 expression [49]. Moreover, a systematic review and meta-analysis points out that the PBM is capable of reduce considerably TNF-α expression in models of joint inflammation [47]. The results of the present study for IL-8 and TNF-α cytokines can be justified by type and modality of the load used in physical exercises once it is suggested that maximum training load seems to modulate the levels of these cytokine [51].

CTX-II is a biomarker released due to the degeneration of cartilage related to catabolic activity that leads to loss of type II collagen concentration, which is the most abundant protein of the cartilage matrix and proteoglycan matrix of cartilage [52]. There was no statistically significant difference in CTX-II levels in this study. These findings do not corroborate those of with Nambi et al. [1], which demonstrated that a protocol of PBM (905 nm, super pulsed, 1.5 J per point, 12 J per knee) and exercise in patients with knee OA during 4 weeks (twice a week) were able of inhibiting CTX-II, MMP-3 (stromelysin), MMP-8 (collagenase-2), and MMP-13 (collagenase-3) expression. However, the study mentioned analyse the levels of CTX-II fragments from urinary fraction and our study evaluated from the serum fraction of peripheral blood samples and this difference in analyse can justify the results of the present study.

In addition, it may be suggested that PBM application, through a cluster device constitutes an advantage for treating patients with knee OA, allowing the irradiation of a larger area and optimizing the treatment [21]. Although some positive effects of the treatments in the patients in this study, some limitations can be raised as a minor number of patients in sample size. It would be extremely important to assess the presence of inflammatory markers in the synovial fluid, which would increase the accuracy of their analysis, as well as the possibility of correlating them with symptomatic variables. Also, there is an absence of a follow-up in order to provide information about the maintenance of results over time in these patients.

Conclusion

The results of this study demonstrated that the physical exercise program in association with PBM was capable of increasing IL-10 levels, and the physical exercise program improved the function capacity. However, PBM did not promote an additional effect to the positive effects of exercise in improving pro-inflammatory and cartilage degradation biomarkers, and functional capacity in women with knee OA. Thus, more studies need to be carried out, using other parameters, since the literature demonstrates heterogeneity in the parameters of treatment with PBM when associated with physical exercise, for the consolidation of an intervention protocol for patients with knee OA.

Clinical messages

-

Patients who underwent physical exercise program in association with PBM for 8 weeks showed improvement in IL-10 levels after treatment and when compared to the control group who did not any intervention;

-

The function capacity was improved in patients undergoing a physical exercise program;

-

Only the control group had the pro-inflammatory marker (IL-1β) increased;

-

Physical exercise program and its association with PBM had no effect on others pro-inflammatory and cartilage degradation biomarkers.

Availability of data and materials

Study data can be made available upon reasonable request to the principal investigator.

Abbreviations

- OA:

-

Osteoarthritis

- TNF-α:

-

Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha

- IL-1β:

-

Interleukin-1β

- IL-6:

-

Interleukin -6

- MMPs:

-

Matrix metalloproteinases

- CTX-II:

-

C-telopeptide of type II collagen

- NSAIDs:

-

Nonsteroidal and steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- MPA:

-

Moderate physical activity

- ILs:

-

Interleukins

- LLLT:

-

Low-level laser therapy

- PBM:

-

Photobiomodulation

- WOMAC:

-

Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index

- LED:

-

Light-emitting diode

- ESP:

-

Exercise sham photobiomodulation group

- EAP:

-

Exercise active photobiomodulation group

- CG:

-

Control group

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays

- SLR:

-

Seated leg raise

- RM:

-

Repetition maximum

References

S GN, Kamal W, George J, Manssor E. Radiological and biochemical effects (CTX-II, MMP-3, 8, and 13) of low-level laser therapy (LLLT) in chronic osteoarthritis in Al-Kharj, Saudi Arabia. Lasers Med Sci. 2017; 32(2):297–303.

Duan ZX, Huang P, Tu C, Liu Q, Li SQ, Long ZL, Li ZH. MicroRNA-15a-5p regulates the development of osteoarthritis by targeting PTHrP in chondrocytes. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019(5):3904923. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/3904923.

Wojdasiewicz P, Poniatowski ŁA, Szukiewicz D. The role of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014: 561459. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/561459.

Al-Khazraji BK, Appleton CT, Beier F, Birmingham TB, Shoemaker JK. Osteoarthritis, cerebrovascular dysfunction and the common denominator of inflammation: a narrative review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2018;26(4):462–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2018.01.011.

Tomazoni SS, Frigo L, Dos Reis Ferreira TC, Casalechi HL, Teixeira S, de Almeida P, Muscara MN, Marcos RL, Serra AJ, de Carvalho PTC, Leal-Junior ECP. Effects of photobiomodulation therapy and topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug on skeletal muscle injury induced by contusion in rats-part 1: morphological and functional aspects. Lasers Med Sci. 2017;32(9):2111–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-017-2346-z.

Nefla M, Holzinger D, Berenbaum F, Jacques C. The danger from within: alarmins in arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12(11):669–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-017-2346-z.

Severino RM, Jorge PB, Martinelli MO, deLima MV, Severino NR, Duarte Junior A. Analysis on the serum levels of the biomarker CTX-II in professional indoor soccer players over the course of one season. Rev Bras Ortop. 2015;50(3):331–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rboe.2015.04.001.

Saberi Hosnijeh F, Siebuhr AS, Uitterlinden AG, Oei EH, Hofman A, Karsdal MA, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Bay-Jensen AC, van Meurs JB. Association between biomarkers of tissue inflammation and progression of osteoarthritis: evidence from the Rotterdam study cohort. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;1(18):81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-016-0976-3.

Rannou F. [Prescribe non-pharmacological treatments for lower limb osteoarthritis?]. Rev Prat 2012; 62(5):651–3. Review. French.

Wyszyńska J, Bal-Bocheńska M. Efficacy of high-intensity laser therapy in treating knee osteoarthritis: a first systematic review. Photomed Laser Surg. 2018;36(7):343–53. https://doi.org/10.1089/pho.2017.4425.

Bennell KL, Hall M, Hinman RS. Osteoarthritis year in review 2015: rehabilitation and outcomes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2016;24(1):58–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2015.07.028.

Castrogiovanni P, Di Rosa M, Ravalli S, et al. Moderate physical activity as a prevention method for knee osteoarthritis and the role of synoviocytes as biological key. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(3):511. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20030511.

Aguiar GC, Do Nascimento MR, De Miranda AS, Rocha NP, Teixeira AL, Scalzo PL. Effects of an exercise therapy protocol on inflammatory markers, perception of pain, and physical performance in individuals with knee osteoarthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35(3):525–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-014-3148-2.

Assis L, Milares LP, Almeida T, Tim C, Magri A, Fernandes KR, Medalha C, Muniz Renno AC. Aerobic exercise training and low-level laser therapy modulate inflammatory response and degenerative process in an experimental model of knee osteoarthritisin rats. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2016;24:169–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-014-3148-2.

Balbinot G, Schuch CP, Nascimento PSD, Lanferdini FJ, Casanova M, Baroni BM, Vaz MA. Photobiomodulation therapy partially restores cartilage integrity and reduces chronic pain behavior in a rat model of osteoarthritis: involvement of spinal glial modulation. Cartilage. 2019;30:1947603519876338. https://doi.org/10.1177/1947603519876338.

Hamblin MR. Mechanisms and applications of the anti-inflammatory effects of photobiomodulation. AIMS Biophys. 2017;4(3):337–61. https://doi.org/10.3934/biophy.2017.3.337.

Assis L, Tim C, Magri A, Fernandes KR, Vassão PG, Renno ACM. Interleukin-10 and collagen type II immunoexpression are modulated by photobiomodulation associated to aerobic and aquatic exercises in an experimental model of osteoarthritis. Lasers Med Sci. 2018;33(9):1875–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-018-2541-6.

de Oliveira VL, Silva JA Jr, Serra AJ, Pallotta RC, da Silva EA, de Farias Marques AC, Feliciano RD, Marcos RL, Leal-Junior EC, de Carvalho PT. Photobiomodulation therapy in the modulation of inflammatory mediators and bradykinin receptors in an experimental model of acute osteoarthritis. Lasers Med Sci. 2017;32(1):87–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-016-2089-2.

Soleimanpour H, Gahramani K, Taheri R, Golzari SE, Safari S, Esfanjani RM, Iranpour A. The effect of low-level laser therapy on knee osteoarthritis: prospective, descriptive study. Lasers Med Sci. 2014;29(5):1695–700. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-014-1576-6.

Alghadir A, Omar MT, Al-Askar AB, Al-Muteri NK. Effect of low-level laser therapy in patients with chronic knee osteoarthritis: a single-blinded randomized clinical study. Lasers Med Sci. 2014;29(2):749–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-013-1393-3.

de Paula Gomes CAF, Leal-Junior ECP, Dibai-Filho AV, de Oliveira AR, Bley AS, Biasotto-Gonzalez DA, de Tarso Camillo de Carvalho P. Incorporation of photobiomodulation therapy into a therapeutic exercise program for knee osteoarthritis: A placebo-controlled, randomized, clinical trial. Lasers Surg Med 2018; 50(8):819–828. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/lsm.22939.

Alfredo PP, Bjordal JM, Junior WS, Lopes-Martins RÁB, Stausholm MB, Casarotto RA, Marques AP, Joensen J. Long-term results of a randomized, controlled, double-blind study of low-level laser therapy before exercises in knee osteoarthritis: laser and exercises in knee osteoarthritis. Clin Rehabil. 2018;32(2):173–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215517723162.

Alayat MSM, Atya AM, Ali MME, Shousha TM. Correction to: Long-term effect of high-intensity laser therapy in the treatment of patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized blinded placebo-controlled trial. Lasers Med Sci. 2020;35(1):297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-019-02926-x.Erratumfor:LasersMedSci.201429(3):1065-73.

de Matos Brunelli Braghin R, Libardi EC, Junqueira C, Rodrigues NC, Nogueira-Barbosa MH, Renno ACM, Carvalho de Abreu DC. The effect of low-level laser therapy and physical exercise on pain, stiffness, function, and spatiotemporal gait variables in subjects with bilateral knee osteoarthritis: a blind randomized clinical trial. Disabil Rehabil 2019; 41(26):3165–3172. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1493160.

Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16:485–93.

Organización Panamericana de la Salud. XXXVI Reunión del Comité Asesor de Investigaciones en Salud. Encuesta Multicéntrica: Salud Bienestar y Envejecimiento (SABE) en América Latina y el Caribe [Internet]. 2011 Washington, D.C: Organización Panamericana de la Salud; Disponível em: http://envejecimiento.csic.es/documentos/documentos/paho-salud-01.pdf

» http://envejecimiento.csic.es/documentos/documentos/paho-salud-01.pdf

Abd El-Kader SM, Al-Shreef FM, Al-Jiffri OH. Impact of aerobic exercise versus resisted exercise on endothelial activation markers and inflammatory cytokines among elderly. Afr Health Sci. 2019;19(4):2874–80. https://doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v19i4.9.

Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15(12):1833–40.

Choquette D, Bellamy N, Raynauld JP. A French-Canadian version of the WOMAC osteoarthritis index. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:S226.

Silva LE, Valim V, Pessanha AP, Oliveira LM, Myamoto S, Jones A, Natour J. Hydrotherapy versus conventional land-based exercise for the management of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized clinical trial. Phys Ther. 2008;88:12–21. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20060040.

Foley A, Halbert J, Hewitt T, Crotty M. Does hydrotherapy improve strength and physical function in patients with osteoarthritis–a randomised controlled trial comparing a gym based and a hydrotherapy based strengthening programme. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:1162–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2002.005272.

American Geriatrics Society Panel on Exercise and Osteoarthritis. Exercise prescription for older adults with osteoarthritis pain: consensus practice recommendations. A supplement to the AGS Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of chronic pain in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001; 49(6):808–823 Review. Erratum in: J Am Geriatr Soc 2001 Oct;49(10):1400

World Association of Laser Therapy (WALT). Consensus agreement on the design and conduct of clinical studies with low- level laser therapy and light therapy for musculoskeletal pain and disorders. Photomed Laser Surg. 2006;24:761–2.

Alcalde GE, Fonseca AC, Bôscoa TF, et al . Effect of aquatic physical therapy on pain perception, functional capacity and quality of life in older people with knee osteoarthritis: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2017; 18(1):317. Published 2017 Jul 11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-017-2061-x.

Alfredo PP, Bjordal JM, Dreyer SH, Meneses SR, Zaguetti G, Ovanessian V, Fukuda TY, Junior WS, Lopes Martins RÁ, Casarotto RA, Marques AP. Efficacy of low level laser therapy associated with exercises in knee osteoarthritis: a randomized double-blind study. Clin Rehabil. 2012;26:523–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2255-4971(15)30407-9.

Kheshie AR, Alayat MS, Ali MM. High-intensity versus low-level laser therapy in the treatment of patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Lasers Med Sci. 2014;29(4):1371–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-014-1529-0.

Nazari A, Moezy A, Nejati P, Mazaherinezhad A. Efficacy of high-intensity laser therapy in comparison with conventional physiotherapy and exercise therapy on pain and function of patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial with 12-week follow up. Lasers Med Sci. 2019;34(3):505–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-018-2624-4.

Kwon JY, Lee SH, Na HS, Jung K, Choi J, Cho KH, Lee CY, Kim SJ, Park SH, Shin DY, Cho ML. Kartogenin inhibits pain behavior, chondrocyte inflammation, and attenuates osteoarthritis progression in mice through induction of IL-10. Sci Rep. 2018; 14;8(1):13832. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32206-7.

Bader DL, Salter DM, Chowdhury TT. Biomechanical influence of cartilage homeostasis in health and disease. Arthritis. 2011;2011:979032. doi: https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/979032. Epub 2011 Sep 15. PMID: 22046527; PMCID: PMC3196252.

Cifuentes DJ, Rocha LG, Silva LA, Brito AC, Rueff-Barroso CR, Porto LC, Pinho RA. Decrease in oxidative stress and histological changes induced by physical exercise calibrated in rats with osteoarthritis induced by monosodium iodoacetate. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18(8):1088–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2010.04.004.

Pigatto GR, Silva CS, Parizotto NA. Photobiomodulation therapy reduces acute pain and inflammation in mice. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2019;196: 111513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2019.111513.

Li K, Liang Z, Zhang J, Zuo X, Sun J, Zheng Q, Song J, Ding T, Hu X, Wang Z. Attenuation of the inflammatory response and polarization of macrophages by photobiomodulation. Lasers Med Sci. 2020;35(7):1509–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-019-02941-y.

Casalechi HL, Leal-Junior EC, Xavier M, Silva JA Jr, de Carvalho PD, Aimbire F, Albertini R. Low-level laser therapy in experimental model of collagenase-induced tendinitis in rats: effects in acute and chronic inflammatory phases. Lasers Med Sci. 2013;28(3):989–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-012-1189-x.

Kapoor M, Martel-Pelletier J, Lajeunesse D, Pelletier JP, Fahmi H. Role of proinflammatory cytokines in the pathophysiology of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7(1):33–42. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2010.196.

Sanches M, Assis L, Criniti C, Fernandes D, Tim C, Renno ACM. Chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine sulfate associated to photobiomodulation prevents degenerative morphological changes in an experimental model of osteoarthritis in rats. Lasers Med Sci. 2018;33(3):549–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-017-2401-9.

Nambi G. Does low level laser therapy has effects on inflammatory biomarkers IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and MMP-13 in osteoarthritis of rat models-a systemic review and meta-analysis. Lasers Med Sci. 2021;36(3):475–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-020-03124-w.

Alves AC, Vieira R, Leal-Junior E, dos Santos S, Ligeiro AP, Albertini R, Junior J, de Carvalho P. Effect of low-level laser therapy on the expression of inflammatory mediators and on neutrophils and macrophages in acute joint inflammation. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15(5):R116. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar4296.

Hoff P, Buttgereit F, Burmester GR, Jakstadt M, Gaber T, Andreas K, Matziolis G, Perka C, Röhner E. Osteoarthritis synovial fluid activates pro-inflammatory cytokines in primary human chondrocytes. Int Orthop. 2013;37(1):145–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-012-1724-1.

Langella LG, Casalechi HL, Tomazoni SS, Johnson DS, Albertini R, Pallotta RC, Marcos RL, de Carvalho PTC, Leal-Junior ECP. Photobiomodulation therapy (PBMT) on acute pain and inflammation in patients who underwent total hip arthroplasty-a randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lasers Med Sci. 2018;33(9):1933–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-018-2558-x.

Helmark IC, Mikkelsen UR, Børglum J, Rothe A, Petersen MC, Andersen O, Langberg H, Kjaer M. Exercise increases interleukin-10 levels both intraarticularly and peri-synovially in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(4):R126. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar3064.

Greiwe JS, Cheng B, Rubin DC, Yarasheski KE, Semenkovich CF. Resistance exercise decreases skeletal muscle tumor necrosis factor alpha in frail elderly humans. FASEB J. 2001;15(2):475–82. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.00-0274com.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo – 2016/08503–0.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PGV, HTT and ACR–Conceptualization, methodology, data collection, writing-original draft preparation and editing; RMDSC and LAG–methodology, statistic work, writing-reviewing and editing. CFDS—biomedicine responsible for blood sample collection from volunteers. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of University (Approval Number 1368478) and, registered in www.clinicaltrials.gov, RBR-7t6nzr. All participants gave their informed consent before participation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare(s) that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vassão, P.G., de Souza, A.C.F., da Silveira Campos, R.M. et al. Effects of photobiomodulation and a physical exercise program on the expression of inflammatory and cartilage degradation biomarkers and functional capacity in women with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized blinded study. Adv Rheumatol 61, 62 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42358-021-00220-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42358-021-00220-5