Abstract

Background

Recommendations of the Myopathy Committee of the Brazilian Society of Rheumatology for the management and therapy of systemic autoimmune myopathies (SAM).

Main body

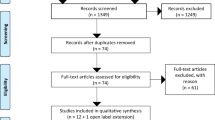

The review of the literature was done in the search for the Medline (PubMed), Embase and Cochrane databases including studies published until June 2018. The Prisma was used for the systematic review and the articles were evaluated according to the levels of Oxford evidence. Ten recommendations were developed addressing the management and therapy of systemic autoimmune myopathies.

Conclusions

Robust data to guide the therapeutic process are scarce. Although not proven effective in controlled clinical trials, glucocorticoid represents first-line drugs in the treatment of SAM. Intravenous immunoglobulin is considered in induction for refractory cases of SAM or when immunosuppressive drugs are contra-indicated. Consideration should be given to the early introduction of immunosuppressive drugs. There is no specific period determined for the suspension of glucocorticoid and immunosuppressive drugs when individually evaluating patients with SAM. A key component for treatment in an early rehabilitation program is the inclusion of strength-building and aerobic exercises, in addition to a rigorous evaluation of these activities for remission of disease and the education of the patient and his/her caregivers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Systemic autoimmune myopathies (SAM) are a heterogeneous group of autoimmune diseases associated with high morbidity and functional disability [1]. Considering its epidemiological, clinical, laboratory and histopathological features, SAM can be classified as dermatomyositis, juvenile dermatomyositis, clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis, polymyositis, inclusion body myositis, immune-mediated necrotizing myopathies and cancer-associated myopathies [1, 2].

Treatments of SAM include not only inflammatory process suppression, but also prevention against musculoskeletal tissue and extra-muscular organ damages. However, robust data are scarce and the therapeutic process is based mainly on observational studies, retrospective analysis and/or small samples of patients [3, 4].

Therefore, the purpose of these recommendations is to guide the treatment of adult patients with SAM, highlighting dermatomyositis and polymyositis, according to current evidence in the literature, facilitating access to available therapies and minimize irreversible disease damages.

Methods

A systematic literature review was performed with the following databases: Medline (Pubmed), Embase and Cochrane. The research strategy was performed according to each “PICO” question (Patient, Intervention, Control and Outcome) elaborated by rheumatologists with experience in the treatment of SAM.

The following English terms were used in the systematic review of the literature: (Muscular Disease OR Myopathies OR Muscle Disorders OR Muscle Disorders OR Myopathic Conditions OR Myopathic Conditions) AND (Autoimmune OR Autoimmune Disease OR Autoimmune Diseases OR Systemic OR Polymyositis OR Idiopathic Polymyositis OR Idiopathic OR Dermatomyositis OR Dermatopolymyositis OR Dermatopolymyositis OR Myositis OR Inflammatory Muscle Diseases OR Inflammatory Myopathy OR Inflammatory Myopathies OR Inclusion Body Myositis OR Inclusion Body Myopathy, Cyclosporine OR Cyclophosphamide OR Methotrexate OR Azathioprine OR Infliximab OR Tumor Necrosis Factor - alpha AND (Therapy / Broad [filter]).

With the application of the random filter, the terms related to each modality of induction treatment for patients with SAM were added.

Inclusion criteria for studies in this systematic review were: randomized and controlled trials (RCTs) addressing SAM treatment, extension studies made from RCTs with the criteria mentioned and systematic reviews with RCT meta-analyzes. In some cases, historical cohort studies and review articles were included and, in the absence of RCTs for specific modalities of therapy, open studies or low quality cohort studies were included.

The steps in this systematic review of the literature followed the Prisma guidelines [5]. The selected studies were evaluated and the degree of recommendation for each question was based on the level of evidence from the studies (Tables 1 and 2) [6,7,8]. Ten recommendations were developed to address different aspects of SAM therapy (Table 3).

Recommendations

What are the general and educational recommendations for SAM?

Literature review and analysis. In general, the education of individuals with SAM, as well as their families and/or caregivers, is of great importance, since they are looking for environmental adaptations and implementation of rehabilitation programs aiming to maintain/improve the patient’s quality of life.

Immunodeficient patients due to the use of medications should be advised about hygiene, maintenance of good nutritional status, avoidance of vaccines with live infectious agents and contact with infectious contagious diseases (B) [9].

When pulmonary dysfunction results from weakness of the diaphragmatic muscles and thoracic muscular wall, respiratory rehabilitation (kinesiotherapy) may be indicated to reduce dyspnea and increase exercise capacity (B) [10].

In case where muscle weakness at the level of the upper third of the esophagus leads to dysphagia, regurgitation or aspiration, dietary changes and swallowing training may be employed. In selected cases, cricopharyngeal myotomy and botulinum toxin application may be necessary (B) [9] (C) [11, 12]. In more severe patients a nasogastric tube or gastrostomy feeding may be recommended to reduce the risk of aspiration and pneumonia (C) [13] (D) [9].

What are some precautions before immunosuppression in patients with SAM?

Literature review and analysis. Glucocorticoids (GC) affect the adaptive and innate immunity processes and increase the risk of acute infections and reactivation of chronic infections caused by fungi, bacteria, viruses and parasites, which can lead to serious disseminated diseases (B) [14]. In addition to specific prophylactic and vaccine recommendations, the use of antibiotics at the first signs of bacterial infection is required (B) [14].

Pneumonia by Pneumocystis jiroveci is a complication in immunocompromised patients and is seen in individuals submitted to high doses GC or other immunosuppressive treatments (B) [15, 16] (C) [17, 18]. Despite the controversies and lack of available evidence, prophylaxis for pneumocystosis should be considered, particularly in the presence of risk factors (e.g., interstitial lung diseases - ILD, other immunosuppressive drugs, patients with anti-MDA-5), for patients who use ≥20 mg/day of prednisone or its equivalent for a period of more than four weeks (B) [19, 20] (D) [21] (C) [22,23,24].

Due to the risk of reactivation of latent tuberculosis, patients undergoing immunosuppressive therapy who present a positive tuberculin test (≥ 5 mm), even with a chest X-ray without evidence of a cicatricial lesion are candidates for prophylaxis (C) [25]. Doses equal to or higher than 15 mg/day of prednisone for a period of more than one month or another immunosuppressive therapy are considered as a risk for the progression of tuberculosis from its latent form to the active form (B) [26,27,28]. Screening for exposure to tuberculosis, as well as obtaining the patient’s medical history, can identify risk factors such as contact with an infected person, residence in an endemic area or abuse of illicit substances. In these individuals, prophylaxis with isoniazid should be considered at a dose of 5 to 10 mg/kg per body weight (maximum dose of 300 mg/day) for 9 months [29].

In immunosuppressed patients, an infestation caused by Strongyloides stercoralis is associated with a high mortality rate even years after exposure (B) [30]. Screenings should be considered in patients with risk factors (e.g., travels to or inhabitants of endemic or high incidence areas of the disease) and who are initiating therapy with immunosuppressive drugs such as GC. Although there is no evidence guiding the prophylaxis of strongylodiasis, ivermectin with immunosuppressive drugs and pulse therapy with methylprednisolone prior to the start of treatment is considered in endemic areas (A) [31] (D) [32].

Immunosuppressive drugs may lead to a lack of vaccinal immune response or the development of active infections when exposed to vaccines consisting of live attenuated viruses. At the moment, there is no solid evidence on the recommendation of the vaccine process of immunocompromised individuals, but for those requiring high doses of GC (≥ 20 mg/day of prednisone or its equivalent for more than two weeks), vaccination is recommended for Haemophilus influenzae type B and the hepatitis A and B, human papillomavirus, influenza, Neisseria meningitidis, measles, mumps and rubella, Streptococcus pneumoniae and tetanus (B) [33, 34]. Individuals who have not received the updated vaccines should receive the vaccine prior to taking immunosuppressive drugs, especially those composed of live viruses due to its contraindication during immunosuppression (D) [35, 36].

Due to the lack of data, specific recommendations guiding the start of treatment with immunosuppressive drugs after immunization with live-attenuated virus vaccines vary. A minimum waiting period of two to four weeks, an estimated time to allow the establishment of an immune response and elimination of live viruses, is advocated (A) [37].

Vigorous hydration to increase urine output and intravenous 2-mercaptethane sulfonate (MESNA) were recommended for prophylaxis of cyclophosphamide-induced hemorrhagic cystitis (C) [38].

Patients should be assessed for fracture risk and bone preserving agents and be prescribed calcium and vitamin D supplementation (B) [39]. Bisphosphonates remain the first choice of treatment in GC-treated patients with high fracture risk (A) [40].

What drug treatment is indicated in the initial treatment of SAM?

Literature review and analysis. Although they have not been tested in controlled clinical trials, GC represent first-line drugs in the treatment of SAM with recommended initial doses of 0.5 to 1.0 mg/kg/day of prednisone for at least 4 weeks (C) [41,42,43]. (Fig. 1). However, depending on the severity of the disease, lower doses, which are associated with fewer adverse events, can be used. In severe cases, such as patients with marked muscle weakness, ulcerated skin lesions, ILD and severe dysphagia, the use of intravenous methylprednisolone (MP) pulse therapy (1 g/day for three consecutive days) followed by a high dose of GC via oral route should be considered (C) [44] (B) [41].

There have no sufficient studies showing the appropriate timing for initiating GC. However, it is possible that an early drug intervention allows a rapid remission of the disease, a lower frequency of relapses and/or a good prognosis of MAS (C) [45, 46]. Moreover, the GC treatment should not be postponed in order to perform an appropriate investigation (e.g., muscle biopsy) (C) [47, 48]. Of note, GC use does not influence the presence or the degree of inflammatory cell infiltration found in muscle biopsies in dermatomyositis / polymyositis with clinical and laboratory disease activity (C) [47, 48].

GC typically results in the normalization of serum levels of muscle enzymes and clinical improvement in muscle strength. However, more than half of patients (B) [49] do not present a complete response to the use of these drugs, and several factors may contribute to response to treatment including disease subtype, onset of therapy, antibody profile or the presence of cancer [41].

Patients with a long period between the muscle symptoms onset and the institution of drug treatment are less likely to present a complete response to GC (B) [49].

Among those who do not present clinical improvement with GC, the reassessment of the diagnosis, the development of myopathy induced by the use of GC or the appearance of malignancy should be verified (D) [50]. For those who present reactivation of the disease by reducing GC doses, methotrexate, azathioprine and/or cyclosporine are the most frequently used in clinical practice, despite the absence of controlled trials evaluating their efficacy (B) [44, 51,52,53,54,55].

The use of intravenous immunoglobulin (dose of 2 g/kg divided into 2 to 5 days) is considered for refractory cases of SAM or when immunosuppressive drugs are contra-indicated, such as during of an infectious process (B) [54]. Evidence, however, on the efficacy of intravenous immunoglobulin as first-line treatment of SAM is controversial (B) [56, 57] (A) [58].

What are the recommended drug treatments for refractory SAM cases?

Literature review and analysis. Patients with SAM who failed conventional therapy were treated with oral tacrolimus (0.075 mg/kg/day) and showed an improvement in muscle strength, a reduction in levels of CK and a mean dose of GC (C) [59].

Case reports have demonstrated favorable results for cyclosporine use (mean dose of 3.5 mg/kg/day) in refractory SAM patients which an improvement in serum levels of CK and muscle strength (C) [60,61,62,63].

Intravenous cyclophosphamide pulses in patients with refractory SAM result in improved muscle strength (C) [64, 65]. In addition, it is possible that its association with methotrexate normalizes the serum levels of CK (C) [65].

Mycophenolate mofetil (1.0 g to 1.5 g twice a day) may be an effective GC-sparing therapy for the treatment of some patients with SAM [66]. This response was based on an improvement in skin disease as judged clinically, an increase in strength and/or an ability to decrease or discontinue concomitant therapies (C) [66].

Leflunomide appears to be effective and safe as an adjuvant drug in refractory dermatomyositis with primarily cutaneous activities (C) [67].

Intravenous immunoglobulin, alone or in combination with immunosuppressive drugs, has a good therapeutic response, mainly in refractory cases (C) [68] (B) [69, 70].

Clinical trials analyzed patients with refractory SAM treated with anti TNFs [71,72,73]. Among the patients who completed the study, there was no improvement in muscle strength [72]. In fact, some patients presented an exacerbation of their disease, elevation of muscle enzyme levels, unchanged rashes [69] and no significant treatment effect on functional outcome [74]. Thus, the use of anti-TNFs are not recommended.

A phase IIb clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of abatacept in patients with refractory SAM demonstrated few serious adverse effects in approximately half of the patients’ responses based on the criteria established by the International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group (IMACS) (B) [75].

Tocilizumab demonstrated efficacy in reports of patients with refractory polymyositis, with a normalization of CK levels, resolution of muscle inflammation in magnetic resonance imaging and reduction of GC doses (C) [76].

Although numerous reports and case series have demonstrated the beneficial effects of rituximab, experience in refractory SAM is still limited (C) [77,78,79,80,81] (B) [82,83,84].

A multicenter clinical trial known as the “Rituximab In Myositis” trial did not reach its primary endpoint (response in the 8th week in the group treated early in relation to the late intervention group), but in the 44th week of follow-up, the majority of patients (83%) reached the definition of response to treatment based on the criteria established by the IMACS [85]. In this study, serious adverse events attributed to rituximab were observed, most of which were represented by infections (B) [82]. Reanalysis of the data obtained in this study was conducted, and individuals who were positive for the anti-synthase and anti-Mi-2 autoantibodies presented better clinical responses (B) [86].

A multicenter phase II study evaluated the efficacy of rituximab in individuals with SAM with anti-synthetase autoantibodies refractory to conventional treatment (GC and at least two immunosuppressive drugs) demonstrated that the majority of these patients had an increase in the Manual Muscle Testing (MMT)-8 followed by a reduction of CK levels and a reduction in the dose of GC (B) [87].

What initial dose of GC should be used and for how long in patients with SAM?

Literature review and analysis. With different regimens of use and routes of administration, the generally recommended starting doses of prednisone, or its equivalent, range from 0.5 to 1.0 mg/kg/day given in divided doses, daily or every other day (C) [88] (B) [89,90,91]. Although there are no controlled clinical trials evaluating the optimal rate of GC reduction, dose reduction should be based on the activity of the disease and the presence of extra-muscular involvement (B) [89,90,91].

Studies have indicated the maintenance of the initial dose over a period of 4 to 8 weeks with monitoring of serum CK levels and muscle strength in addition to other disease manifestations [41, 92, 93]. After this period of time, as long as the disease has been controlled, GC dose can be reduced by 20 to 25% every four weeks until the daily dose of 5 to 10 mg is reached, at which point a stable dose of GC is maintained for another year, depending on the clinical course (C) [41, 92, 93].

In severe cases, MP pulse therapy should be considered (1 g/day for three consecutive days followed by a regimen with oral GC) (C) [41, 42, 92, 93] (B) [41,42,43,44, 49, 93, 94].

Although it is considered a first-line drug, studies have shown that more than half of the patients fail to obtain a complete clinical response to CG in monotherapy and adding other immunosuppressive drugs in often necessary (B) [95, 96].

How long should SAM patients receive immunosuppressive / immunomodulatory drugs after GC discontinuation?

Literature review and analysis. There is no conclusive evidence to establish how long patients with SAM should receive treatment with immunosuppressive and/or immunomodulatory drugs following the discontinuation of GC therapy [97, 98]. Overall, studies show that after disease remission, drug doses can be reduced gradually. Initially, GC dose reduction is suggested and, subsequently, in the maintenance of clinical and laboratory parameters, a reduction in the doses of immunosuppressive/immunomodulatory drugs can be attempted. There is no predetermined treatment duration (B) [97, 98].

What is the evidence on the benefit of association vs. exchange immunosuppressive/immunomodulatory drugs in SAM?

Literature review and analysis. Few comparative studies between immunosuppressive/immunomodulatory drugs support the prescription superiority of one medication over another, between monotherapies or combination treatments [3, 52,53,54, 66, 68,69,70, 99,100,101,102,103,104,105].

In a long-term follow-up, individuals who received MTX and combination of methotrexate and azathioprine showed an improvement in functional status beyond the need for lower doses of maintenance GC (B) [52, 53].

A randomized clinical trial did not verify the difference in muscle function tests in patients who had failed to obtain a clinical response with GC alone and who were randomized to treatment with cyclosporine, methotrexate or cyclosporine/methotrexate combination therapy (B) [100].

Despite weak evidence, studies including a small number of patients have shown improvement in the evolution of extra-muscular disease, muscle strength and inflammatory markers in individuals who did not respond to conventional therapy and who used mycophenolate mofetil in monotherapy or in association (C) [70, 101]. Evidence points mainly to associated therapy for improvements in lung function tests in patients with SAM and ILD (C) [104, 105].

What is the role of rehabilitation, physical exercise and physiotherapy in the treatment of SAM?

Literature review and analysis. Physical rehabilitation through physical exercises and physical therapy for muscle strengthening are beneficial and safe for patients with SAM when indicated two to three weeks after exacerbation of the disease, however this has not always been the guidance since, historically, these patients were discouraged from exercising because of the possibility of disease relapse or damage (B, D) [106,107,108,109,110].

There was evidence of improvement in aerobic capacity and isometric muscle strength without signs of increased inflammation among individuals randomized to exercise assessed by serum levels of CK (B) [111] (C) [112, 113]. Numerous studies have demonstrated the safety and positive results of supervised physical exercise in muscular function indicated for patients with SAM (B) [110] (A) [111]. Moreover, physical exercise can prevent the process of muscle atrophy caused by inflammation, physical inactivity and treatment with GC (D) [114].

In addition to improving muscle strength and increasing maximal oxygen uptake through resistance training, patient experienced the reduced expression of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic genes, with significant positive impact on molecular profile and improvement in functional capacity (B) [115,116,117,118,119].

Evidence indicates that physical exercise has the potential to reduce disease activity in established cases of SAM and aerobic exercises may be more effective in reducing disease activity than strength and resistance exercises (B) [119,120,121].

How to monitor disease activity (biomarkers) in patients with SAM?

Literature review and analysis. Levels of interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, TNF and interferon gamma induced protein 10 (IP-10) can be used as biomarkers to monitor disease activity and pulmonary involvement (B) [122,123,124,125].

Several cytokines have been identified as a possible prognosis biomarker in SAM: TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand, IL-8, macrophage migration inhibitory factor, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, leukemia inhibitory factor, IP-10 and interferon-α2 showed significant changes after treatment with methotrexate (B) [126, 127].

It was also verified that the loss of muscle strength was associated with changes in the serum levels of IL-8, IL-12 and stromal cell-derived factor 1 (B) [125].

Additional results showed that changes in serum levels of cytokines (IL-6, IL-8 and TNFα) were positively correlated with changes in the evaluation of muscular strength and visual analogue scale regardless of treatment (B) [125].

Levels of some biomarkers, such as TNF-α-activating factor B, were elevated in some subgroups of patients with SAM, especially those with active or positive anti-Jo-1 disease (B) [128].

Elevated serum levels of the Krebs von den Lungen-6 are directly associated with pulmonary involvement with a manifestation of ILD, and these levels are inversely correlated to the variables studied through the pulmonary function test, which presents findings corresponding to a restrictive respiratory pattern (B) [129,130,131].

Other proposed biomarkers that are elevated in patients with active SAM, are represented by adipokines such as MRP8/14, galectin-9, TNF-type II receptor, CXCL10, and myositis-specific antibodies (B) [132,133,134,135,136].

Autoantibody titers demonstrated association with disease activity. A decrease in serum levels of anti-Mi-2, anti-Jo-1 and TIF-1 after treatment of SAM was detected in many cases (B) [137]. High levels of serum ferritin was also found in patients with SAM and ILD, and evidence suggests that this may be used as a prognostic marker (B) [137].

Of note, high serum levels of CK are the hallmark of muscle involvement [138]. CK is released in the serum in case of muscle damage and is the most sensitive muscle enzyme in the acute phase of the disease. Moreover, elevation in serum aldolase, myoglobin, lactate dehydrogenase, aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase also occur [138].

Some patients have selectively increased serum levels of aldolase, which could be associated with syndromes including myopathies with discomfort and weakness, systemic disorders and pathology in perimysial muscle connective tissue (C) [139].

How to define activity versus remission of SAM in clinical practice?

Literature review and analysis. The IMACS has developed an assessment tool that provides appropriate clinical measures of disease status and which, together, assesses 6 items related to its activity. These items include overall evaluation of disease activity perceived by the patient and physician, accessed by an Likert scale or analogue visual scale; muscle strength assessed by MMT; muscle function measured by the Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI); and muscle enzyme sera and extra-muscular manifestations of the disease assessed by the Myositis Disease Activity Assessment Tool (MDAAT) (D) [140]. In addition to the MDAAT, the IMACS defined the Myositis Damage Index (MDI) to included irreversible damage from the disease [140].

To evaluate the cutaneous lesions of dermatomyositis, the IMACS developed the CDASI (Cutaneous Disease Activity Score), which assigns scores to active and chronic skin lesions [141]. It is important to note that the IMACS used a consensus methodology to define the clinical response criteria, establishing as a complete clinical response a period of 6 months or more with no evidence of disease activity during treatment and definition for clinical remission as a period equal to or greater than 6 months of inactive disease in the absence of any therapy (D) [141]. According to the IMACS, response to treatment is defined as an improvement of more than 30% in 3 IMACS items, excluding the MMT-8 [141]. The IMACS’s assessment of response to treatment is therefore dichotomous, allowing us to state only whether or not there was improvement [141].

Considering the need for sensitive response criteria at different levels of improvement, the recent ACR/EULAR initiative validated a tool. According to the score, improvement is defined as minimal, moderate or greater. This new assessment tool should be used in upcoming clinical studies evaluating new therapies for SAM [142].

In addition to serum dosage of muscle enzymes, imaging techniques can identify changes in the muscle structure of SAM patients. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been used to evaluate disease activity, guide therapeutic decisions and select the biopsy site when necessary (B) [143]. Patients with active disease may present areas of edema and muscular necrosis in T2-weighted images [143]. In this same examination, areas of muscular atrophy, fatty degeneration, fibrosis and calcification can be evidenced in T1-weighted sequences (B) [144] (D) [145]. It is important to emphasize that there is not yet a universally accepted standardization of the MRI protocol to be used.

Conclusions

Robust data to guide the therapeutic process are scarce. Decision-making is based mainly on observational studies, many of which are retrospective in nature and include a small number of patients.

Although not proven effective in controlled clinical trials, GC represents first-line drugs in the treatment of SAM. Intravenous immunoglobulin is considered in induction for refractory cases of SAM or when immunosuppressive drugs are contra-indicated.

Consideration should be given to the early introduction of immunosuppressive drugs, especially azathioprine, methotrexate and cyclosporine, considering the association of these drugs and, in refractory cases, the use of rituximab. There is no specific period determined for the suspension of GC and immunosuppressive drugs when individually evaluating patients with SAM.

A key component for treatment in an early rehabilitation program is the inclusion of strength-building and aerobic exercises, in addition to a rigorous evaluation of these activities for remission of disease and the education of the patient and his/her caregivers.

Abbreviations

- CK:

-

Creatine phosphokinase

- GC:

-

Glucocorticoid

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- ILD:

-

Interstitial lung disease

- IMACS:

-

International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group

- MDAAT:

-

Myositis Disease Activity Assessment Tool

- MMT:

-

Manual Muscle Testing

- MP:

-

Methylprednisolone

- PICO:

-

Patient, Intervention, Control and Outcome

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trials

- SAM:

-

Systemic autoimmune myopathies

- TNF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor

References

Feldman BM, Rider LG, Reed AM, Pachman LM. Juvenile dermatomyositis and other idiopathic inflammatory myopathies of childhood. Lancet. 2008;371:201–12.

Lundberg IE, Tjamlund A, Bottai M, Pikington C, de Visser M, Alfredson L, et al. 2017 European league against rheumatism/ American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for adult and juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and their major subgroups. Arthritis Rheum. 2017;69:2271–82.

Gordon PA, Winer JB, Hoogendijk JE, Choy EH. Immunosuppressant and immunomodulatory treatment for dermatomyositis and polymyositis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012:CD003643.

Leclair V, Lundberg IE. Recent clinical trials in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2017;29:652–65.

Iberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700.

Oxford centre for evidence-based medicine - Levels of evidence (March 2009) - CEBM. 2009.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Vist GE, Liberati A, GRADE Working Group, et al. Going from evidence to recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:1049–51.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, GRADE Working Group, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924–6.

Kuhn MA, Belafsky PC. Management of cricopharyngeus muscle dysfunction. Otolaryngol Clin N Am. 2013;46:1087–99.

Oh TH, Brumfield KA, Hoskin TL, Stolp KA, Murray JA, Brassford JR. Dysphagia in inflammatory myopathy: clinical characteristics, treatment strategies, and outcome in 62 patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:441–7.

Schrey A, Airas L, Jokela M, Pulkkinen J. Botulinum toxin alleviates dysphagia of patients with inclusion body myositis. J Neurol Sci. 2017;380:142–7.

Moerman M, Callier Y, Dick C, Vermeersch H. Botulinum toxin for dysphagia due to cricopharyngeal dysfunction. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2002;259:1–3.

Sanei-Moghaddam A, Kumar S, Jani P, Brierley C. Cricopharyngeal myotomy for cricopharyngeus stricture in an inclusion body myositis patient with hiatus hernia: a learning experience. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013.

Marie I, Mcnard JF, Hachulla E, Chérin P, Benveniste O, Tiev K, et al. Infectious complications in polymyositis and dermatomyositis: a series of 279 patients. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:48–60.

Gerhart JL, Kalaaji AN. Development of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients with immunobullous and connective tissue disease receiving immunosuppressive medications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:957–61.

Li J, Huang XM, Fang WG, Zeng XJ. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients with connective tissue disease. J Clin Rheumatol. 2006;12:114–7.

Ward MM, Donald F. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients with connective tissue diseases: the role of hospital experience in diagnosis and mortality. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:780–9.

Bachelez H, Schremmer B, Cadranel J, Mouly F, Sarfati C, Agbalika F, et al. Fulminant Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in 4 patients with dermatomyositis. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1501–3.

Yale SH, Limper AH. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients without acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: associated illness and prior corticosteroid therapy. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:5–13.

Kadoya A, Okada J, Iikuni Y, Kondo H. Risk factors for Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients with polymyositis/dermatomyositis or systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 1996;23:1186–8.

Wolfe RM, Peacock JE Jr. Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) and the rheumatologist: which patients are at risk and how can PCP be prevented? Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2017;19:35.

Aymonier M, Abed S, Boy T, Barazzutti H, Fournier B, Morand JJ. Dermatomyositis associated with anti-MDA5 antibodies and Pneumocystis pneumonia: two lethal cases. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2017;144:279–83.

Stern A, Green H, Paul M, Vidal L, Leibovici L. Prophylaxis for Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) in non-HIV immunocompromised patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD005590.

Utsunomiya M, Dobashi H, Odani T, Saito K, Yokogawa N, Nagasaka K, et al. Optimal regimens of sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim for chemoprophylaxis of Pneumocystis pneumonia in patients with systemic rheumatic diseases: results from a non-blinded, randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19:7.

Ravn P, Munk ME, Andersen AB, Lundgren B, Nielsen LN, Lillebaek T, et al. Reactivation of tuberculosis during immunosuppressive treatment in a patient with a positive QuantiFERON-RD1 test. Scand J Infect Dis. 2004;36:499–501.

Jick SS, Lieberman ES, Rahman MU, Choi HK. Glucocorticoid use, other associated factors, and the risk of tuberculosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:19–26.

Chan MJ, Wen YH, Huang YB, Chuang HY, Tain YL, Lily Wang YC, et al. Risk of tuberculosis comparison in new users of anti-tumour necrosis factor and with existing disease-modifying antirheumatic drug therapy. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2018;43:256–64.

Kim HA, Yoo CD, Baek HJ, Lee EB, Ahn C, Han JS, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in a corticosteroid-treated rheumatic disease patient population. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1998;16:9–13.

Health Surveillance Guide, 2017, Ministry of Health.

Lam CS, Tong MK, Chan KM, Siu YP. Disseminated strongyloidiasis: a retrospective study of clinical course and outcome. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;25:14–8.

Santiago M, Leito B. Prevention of strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome: a rheumatological point of view. Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20:744–8.

Davis JS, Currie BJ, Fisher DA, Huffam SE, Anstey NM, Price RN, et al. Prevention of opportunistic infections in immunosuppressed patients in the tropical top end of the Northern Territory. Commun Dis Intell Q Rep. 2003;27:526–32.

Shinjo SK, de Moraes JC, Levy-Neto M, Aikawa NE, de Medeiros Ribeiro AC, Schahin Saad CG, et al. Pandemic unadjuvanted influenza a (H1N1) vaccine in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: immunogenicity independent of therapy and no harmful effect in disease. Vaccine. 2012;31:202–6.

Guissa VR, Pereira RM, Sallum AM, Aikawa NE, Campos LM, Silva CA, et al. Influenza a H1N1/2009 vaccine in juvenile dermatomyositis: reduced immunogenicity in patients under immunosuppressive therapy. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30:583–8.

Bruhler S, Eperon G, Ribi C, Kyburz D, van Gompel F, Visser LG, et al. Vaccination recommendations for adult patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Swiss Med Wkly. 2015;145:w14159.

Papadopoulou D, Sipsas NV. Comparison of national clinical practice guidelines and recommendations on vaccination of adult patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Rheumatol Int. 2014;34:151–63.

van Assen S, Elkayam O, Agmon-Levin N, Cervera R, Doran MF, Dougados M, et al. Vaccination in adult patients with auto-immune inflammatory rheumatic diseases: a systematic literature review for the European league against rheumatism evidence-based recommendations for vaccination in adult patients with auto-immune inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2011;10:341–52.

Matz EL, Hsieh MH. Review of advances in uroprotective agents for cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide-induced hemorrhagic cystitis. Urology. 2017;100:16–9.

Cooper C, Bardin T, Brandi ML, Cacoub P, Caminis J, Civitelli R, et al. Balancing benefits and risks of glucocorticoids in rheumatic diseases and other inflammatory joint disorders: new insights from emerging data. An expert consensus paper from the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO). Aging Clin Exp Res. 2016;28:1–16.

Lems WF, Saag K. Bisphosphonates and glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: cons. Endocrine. 2015;49:628–34.

Bolosiu HD, Man L, Rednic S. The effect of methylprednisolone pulse therapy in polymyositis/dermatomyositis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;455:349–57.

Winkelmann RK, Mulder DW, Lambert EH, Howard FM Jr, Diessner GR. Course of dermatomyositis-polymyositis: comparison of untreated and cortisone-treated patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 1968;43:545–56.

Hoffman GS, Franck WA, Raddatz DA, Stallones L. Presentation, treatment, and prognosis of idiopathic inflammatory muscle disease in a rural hospital. Am J Med. 1983;75:433–8.

Matsubara S, Hirai S, Sawa Y. Pulsed intravenous methylprednisolone therapy for inflammatory myopathies: evaluation of the effect by comparing two consecutive biopsies from the same muscle. J Neuroimmunol. 1997;76:75–80.

Naji P, Shahram F, Nadji A, Davatchi F. Effect of early treatment in polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Neurol India. 2010;58:58–61.

De Souza FHC, Miossi R, Shinjo SK. Necrotising myopathy associated with anti-signal recognition particle (anti-SRP) antibody. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2017;35:766–71.

Pinhata MM. Nascimento, Marie SK, Shinjo SK. Does previous corticosteroid treatment affect the inflammatory infiltrate found in polymyositis muscle biopsies? Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33:310–4.

Shinjo SK, Nascimento JJ, Marie SK. The effect of prior corticosteroid use in muscle biopsies from patients with dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33:336–40.

Joffe MM, Love LA, Leff RL, Fraser DD, Targoff IN, Hicks JE, et al. Drug therapy of the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: predictors of response to prednisone, azathioprine, and methotrexate and a comparison of their efficacy. Am J Med. 1993;94:379–87.

Fry CS, Nayeem SZ, Dillon EL, Sarkar PS, Tumurbaatar B, Urban RJ, et al. Glucocorticoids increase skeletal muscle NF-κB inducing kinase (NIK): links to muscle atrophy. Physiol Rep. 2016;4.

Newman ED, Scott DW. The use of low-dose oral methotrexate in the treatment of polymyositis and dermatomyositis. J Clin Rheumatol. 1995;1:99–102.

Bunch TW, Worthington JW, Combs JJ, Ilstrup DM, Engel AG. Azathioprine with prednisone for polymyositis. A controlled, clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 1980;92:365–9.

Bunch TW. Prednisone and azathioprine for polymyositis: long-term follow-up. Arthritis Rheum. 1981;24:45–8.

Schiopu E, Phillips K, MacDonald PM, Crofford LJ, Somers EC. Predictors of survival in a cohort of patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis: effect of corticosteroids, methotrexate and azathioprine. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:R22.

Yu KH, Wu YJ, Kuo CF, See LC, Shen YM, Chang HC, et al. Survival analysis of patients with dermatomyositis and polymyositis: analysis of 192 Chinese cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:1595–601.

Cherin P, Piette JC, Wechsler B, Bletry O, Ziza JM, Laraki R, et al. Intravenous gamma globulin as first line therapy in polymyositis and dermatomyositis: an open study in 11 adult patients. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:1092–7.

Göttfried I, Seeber A, Anegg B, Rieger A, Stingl G, Volc-Platzer B. High dose intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) in dermatomyositis: clinical responses and effect on sIL-2R levels. Eur J Dermatol. 2000;10:29–35.

Anh-Tu Hoa S, Hudson M. Critical review of the role of intravenous immunoglobulins in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2017;46:488–508.

Oddis CV, Sciurba FC, Elmagd KA, Starzl TE. Tacrolimus in refractory polymyositis with interstitial lung disease. Lancet. 1999;353:1762–3.

Chang HK, Lee DH. Successful combination therapy of cyclosporine and methotrexate for refractory polymyositis with anti-Jo-1 antibody: a case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2003;18:131–4.

Mitsunaka H, Tokuda M, Hiraishi T, Dobashi H, Takahara J. Combined use of cyclosporine a and methotrexate in refractory polymyositis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2000;29:192–4.

Qushmaq KA, Chalmers A, Esdaile JM. Cyclosporin a in the treatment of refractory adult polymyositis/dermatomyositis: population based experience in 6 patients and literature review. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:2855–9.

Villalba L, Hicks JE, Adams EM, Sherman JB, Gourley MF, Leff RL, et al. Treatment of refractory myositis: a randomized crossover study of two new cytotoxic regimens. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:392–9.

Nakashima S, Mori M, Miyamae T, Ito S, Ibe M, Aihara Y, et al. Intravenous cyclophosphamide pulse therapy for refractory juvenile dermatomyositis. Ryumachi. 2002;42:895–902.

Hirano F, Tanaka H, Nomura Y, Matsui T, Makino Y, Fukawa E, et al. Successful treatment of refractory polymyositis with pulse intravenous cyclophosphamide and low-dose weekly oral methotrexate therapy. Intern Med. 1993;32:749–52.

Edge JC, Outland JD, Dempsey JR, Callen JP. Mycophenolate mofetil as an effective corticosteroid sparing therapy for recalcitrant dermatomyositis. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:65–9.

De Souza RC, De Souza FHC, Miossi R, Shinjo SK. Efficacty and safety of leflunomide as na adjuvante drug in refractory dermatomyositis with primarily cutaneous activity. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2017;35:1011–3.

Saito E, Koike T, Hashimoto H, Miyasaka N, Ikeda Y, Hara M, et al. Efficacy of high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in Japanese patients with steroid-resistant polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Mod Rheumatol. 2008;18:34–44.

Dalakas MC, Illa I, Dambrosia JM, Soueidan SA, Stein DP, Otero C, et al. A controlled trial of high-dose intravenous immune globulin infusions as treatment for dermatomyositis. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1993–2000.

Cherin P, Pelletier S, Teixeira A, Laforet P, Genereau T, Simon A, et al. Results and long-term followup of intravenous immunoglobulin infusions in chronic, refractory polymyositis: an open study with thirty-five adult patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:467–74.

Wendling D, Prati C, Ornetti P, Toussirot E, Streit G. Anti TNF-alpha treatment of a refractory polymyositis. Rev Med Interne. 2007;28:194–5.

Dastmalchi M, Grundtman C, Alexanderson H, Mavragani CP, Einarsdottir H, Helmers SB, et al. A high incidence of disease flares in an open pilot study of infliximab in patients with refractory inflammatory myopathies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1670–7.

Iannone F, Scioscia C, Falappone PC, Covelli M, Lapadula G. Use of etanercept in the treatment of dermatomyositis: a case series. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:1802–4.

Amato AA, Tawil R, Kissel J, Barohn R, McDermott MP, Pandya S, et al. A randomized, pilot trial of etanercept in dermatomyositis. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:427–36.

Tjärnlund A, Tang Q, Wick C, Dastmalchi M, Mann H, Tomasová Studýnková J, et al. Abatacept in the treatment of adult dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a randomised, phase IIb treatment delayed-start trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:55–62.

Narazaki M, Hagihara K, Shima Y, Ogata A, Kishimoto T, Tanaka T. Therapeutic effect of tocilizumab on two patients with polymyositis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50:1344–6.

Mahler EA, Blom M, Voermans NC, van Engelen BG, van Riel PL, Vonk MC, et al. Rituximab treatment in patients with refractory inflammatory myopathies. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50:2206–13.

Mok CC, Ho LY, To CH. Rituximab for refractory polymyositis: an open-label prospective study. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:1864–8.

Noss EH, Hausner-Sypek DL, Weinblatt ME. Rituximab as therapy for refractory polymyositis and dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:1021–6.

Sánchez-Fernández SÁ, Carrasco Fernández JA, Rojas Vargas LM. Efficacy of rituximab in dermatomyositis and polymyositis refractory to conventional therapy. Reumatol Clin. 2013;9:117–9.

Frikha F, Rigolet A, Behin A, Fautrel B, Herson S, Benveniste O. Efficacy of rituximab in refractory and relapsing myositis with anti-Jo-1 antibodies: a report of two cases. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48:1166–8.

Unger L, Kampf S, Lüthke K, Aringer M. Rituximab therapy in patients with refractory dermatomyositis or polymyositis: differential effects in a real-life population. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53:1630–8.

Levine TD. Rituximab in the treatment of dermatomyositis: an open-label pilot study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:601–7.

Lambotte O, Kotb R, Maigne G, Blanc FX, Goujard C, Delfraissy JF. Efficacy of rituximab in refractory polymyositis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:1369–70.

Oddis CV, Reed AM, Aggarwal R, Rider LG, Ascherman DP, Levesque MC, RIM Study Group, et al. Rituximab in the treatment of refractory adult and juvenile dermatomyositis and adult polymyositis: a randomized, placebo-phase trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:314–24.

Reed AM, Crowson CS, Hein M, de Padilla CL, Olazagasti JM, Aggarwal R, RIM Study Group, et al. Biologic predictors of clinical improvement in rituximab-treated refractory myositis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:257.

Allenbach Y, Guiguet M, Rigolet A, Marie I, Hachulla E, Drouot L, et al. Efficacy of rituximab in refractory inflammatory myopathies associated with anti-synthetase auto-antibodies: an open-label, phase II trial. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0133702.

van der Kooi AJ, de Visser M. Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;119:495–512.

Dalakas MC. Inflammatory muscle diseases. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1734–47.

Nzeusseu A, Brion F, Lefèbvre C, Knoops P, Devogelaer JP, et al. Functional outcome of myositis patients: can a low-dose glucocorticoid regimen achieve good functional results? Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1999;17:441–6.

van de Vlekkert J, Hoogendijk JE, de Haan RJ, Algra A, van der Tweel I, van der Pol WL, et al. Dexa myositis trial. Oral dexamethasone pulse therapy versus daily prednisolone in sub-acute onset myositis, a randomized clinical trial. Neuromuscul Disord. 2010;20:382–9.

Uchino M, Yamashita S, Uchino K, Hara A, Koide T, Suga T, et al. Long-term outcome of polymyositis treated with high single-dose alternate-day prednisolone therapy. Eur Neurol. 2012;68:117–21.

Seshadri R, Feldman BM, Ilowite N, Cawkwell G, Pachman LM. The role of aggressive corticosteroid therapy in patients with juvenile dermatomyositis: a propensity score analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:989–95.

Raghu P, Manadan AM, Schmukler J, Mathur T, Block JA. Pulse dose methylprednisolone therapy for adult idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. Am J Ther. 2015;22:244–7.

Mathur T, Manadan AM, Thiagarajan S, Hota B, Block JA. Corticosteroid monotherapy is usually insufficient treatment for idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. Am J Ther. 2015;22:350–4.

Mosca M, Neri R, Pasero G, Bombardieri S. Treatment of the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: a retrospective analysis of 63 Caucasian patients longitudinally followed at a single center. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2000;18:451–6.

Bronner IM, van der Meulen MF, de Visser M, Kalmijn S, van Venrooij WJ, Voskuyl AE, et al. Long-term outcome in polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1456–61.

Marie I, Hachulla E, Hatron PY, Hellot MF, Levesque H, Devulder B, et al. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis: short term and longterm outcome, and predictive factors of prognosis. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:2230–7.

Vencovsk J, Jarosov K, Machcek S, Studnkov J, Kafkov J, Bartunková J, et al. Cyclosporine a versus methotrexate in the treatment of polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2000;29:95–102.

Ibrahim F, Choy E, Gordon P, Dor CJ, Hakim A, Kitas G, et al. Second-line agents in myositis: 1-year factorial trial of additional immunosuppression in patients who have partially responded to steroids. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54:1050–5.

Pisoni CN, Cuadrado MJ, Khamashta MA, Hughes GR, D'Cruz DP. Mycophenolate mofetil treatment in resistant myositis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46:516–8.

Majithia V, Harisdangkul V. Mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept): an alternative therapy for autoimmune inflammatory myopathy. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005;44:386–9.

Dagher R, Desjonqures M, Duquesne A, Quartier P, Bader-Meunier B, Fischbach M, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil in juvenile dermatomyositis: a case series. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:711–6.

Mira-Avendano IC, Parambil JG, Yadav R, Arrossi V, Xu M, Chapman JT, et al. A retrospective review of clinical features and treatment outcomes in steroid resistant interstitial lung disease from polymyositis / dermatomyositis. Respir Med. 2013;107:890–6.

Morganroth PA, Kreider ME, Werth VP. Mycophenolate mofetil for interstitial lung disease in dermatomyositis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62:1496–501.

Cea G, Bendahan D, Manners D, Hilton-Jones D, Lodi R, Styles P, et al. Reduced oxidative phosphorylation and proton efflux suggest reduced capillary blood supply in skeletal muscle of patients with dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a quantitative 31P - magnetic resonance spectroscopy and MRI study. Brain. 2002;125:1635–45.

Englund P, Nennesmo I, Klareskog L, Lundberg IE. Interleukin-1 alpha expression in capillaries and major histocompatibility complex class I expression in type II muscle fibers from polymyositis and dermatomyositis patients: important pathogenic features independent of inflammatory cell clusters in muscle tissue. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:1044–55.

Loell I, Lundberg IE. Can muscle regeneration fail in chronic inflammation: a weakness in inflammatory myopathies? J Intern Med. 2011;269:243–57.

Varjú C, Pethö E, Kutas R, Czirják L. The effect of physical exercise following acute disease exacerbation in patients with dermato/polymyositis. Clin Rehabil. 2003;17:83–7.

Bertolucci F, Neri R, Dalise S, Venturi M, Rossi B, Crisari C. Abnormal lactate levels in patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis: the benefits of a specific rehabilitative program. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2014;50:161–9.

Wiesinger GF, Quittan M, Aringer M, Seeber A, Volc-Platzer B, Smolen J, et al. Improvement of physical fitness and muscle strength in polymyositis/dermatomyositis patients by a training programme. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37:196–200.

Hicks JE, Miller F, Plotz P, Chen TH, Gerber L. Isometric exercise increases strength and does not produce sustained creatinine phosphokinase increases in a patient with polymyositis. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:1399–401.

Escalante A, Miller L, Beardmore TD. Resistive exercise in the rehabilitation of polymyositis/dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:1340–4.

Nader GA, Lundberg IE. Exercise as an anti-inflammatory intervention to combat inflammatory diseases of muscle. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2009;21:599–603.

Nader GA, Dastmalchi M, Alexanderson H, Grundtman C, Gernapudi R, Esbjörnsson M, et al. A longitudinal, integrated, clinical, histological and mRNA profiling study of resistance exercise in myositis. Mol Med. 2010;16:455–64.

Munters LA, Loell I, Ossipova E, Raouf J, Dastmalchi M, Lindroos E, et al. Endurance exercise improves molecular pathways of aerobic metabolism in patients with myositis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:1738–50.

Boehler JF, Hogarth MW, Barberio MD, Novak JS, Ghimbovschi S, Brown KJ, et al. Effect of endurance exercise on microRNAs in myositis skeletal muscle - a randomized controlled study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0183292.

Alexanderson H, Munters LA, Dastmalchi M, Loell I, Heimbürger M, Opava CH, et al. Resistive home exercise in patients with recent-onset polymyositis and dermatomyositis - a randomized controlled single-blinded study with a 2-year followup. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:1124–32.

Alemo Munters L, Dastmalchi M, Katz A, Esbjörnsson M, Loell I, Hanna B, et al. Improved exercise performance and increased aerobic capacity after endurance training of patients with stable polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15:R83.

Alemo Munters L, Dastmalchi M, Andgren V, Emilson C, Bergegård J, Regardt M, et al. Improvement in health and possible reduction in disease activity using endurance exercise in patients with established polymyositis and dermatomyositis: a multicenter randomized controlled trial with a 1-year open extension follow-up. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65:1959–68.

Tiffreau V, Rannou F, Kopciuch F, Hachulla E, Mouthon L, Thoumie P, et al. Post rehabilitation functional improvements in patients with inflammatory myopathies: the results of a randomized controlle trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98:227–34.

López De Padilla CM, Crowson CS, Hein MS, Strausbauch MA, Aggarwal R, Levesque MC, et al. Interferon-regulated chemokine score associated with improvement in disease activity in refractory myositis patients treated with rituximab. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33:655–63.

Gono T, Kaneko H, Kawaguchi Y, Hanaoka M, Kataoka S, Kuwana M, et al. Cytokine profiles in polymyositis and dermatomyositis complicated by rapidly progressive or chronic interstitial lung disease. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53:2196–203.

Olazagasti JM, Niewold TB, Reed AM. Immunological biomarkers in dermatomyositis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015;17:68.

Badrising UA, Tsonaka R, Hiller M, Niks EH, Evangelista T, Lochmüller H, et al. Cytokine profiling of serum allows monitoring of disease progression in inclusion body myositis. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2017;4:327–35.

Krystufková O, Vallerskog T, Helmers SB, Mann H, Putová I, Belácek J, et al. Increased serum levels of B cell activating factor (BAFF) in subsets of patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:836–43.

Reed AM, Peterson E, Bilgic H, Ytterberg SR, Amin S, Hein MS, et al. Changes in novel biomarkers of disease activity in juvenile and adult dermatomyositis are sensitive biomarkers of disease course. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:4078–86.

Kobayashi N, Kobayashi I, Mori M, Sato S, Iwata N, Shiguemura T, et al. Increased serum B cell activating factor and a proliferation-inducing ligand are associated with interstitial lung disease in patients with juvenile dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol. 2015;42:2412–8.

Kubo M, Ihn H, Yamane K, Kikuchi K, Yazawa N, Soma Y, et al. Serum KL-6 in adult patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000;39:632–6.

Fathi M, Barbasso Helmers S, Lundberg IE. KL-6: a serological biomarker for interstitial lung disease in patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis. J Intern Med. 2012;271:589–97.

Chen F, Lu X, Shu X, Peng Q, Tian X, Wang G. Predictive value of serum markers for the development of interstitial lung disease in patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis: a comparative and prospective study. Intern Med J. 2015;45:641–7.

Nistala K, Varsani H, Wittkowski H, Vogl T, Krol P, Shah V, et al. Myeloid related protein induces muscle derived inflammatory mediators in juvenile dermatomyositis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15:R131.

Olazagasti JM, Hein M, Crowson CS, de Padilla CL, Peterson E, Baechler EC, et al. Adipokine gene expression in peripheral blood of adult and juvenile dermatomyositis patients and their relation to clinical parameters and disease activity measures. J Inflamm (Lond). 2015;12:29.

Bellutti Enders F, van Wijk F, Scholman R, Hofer M, Prakken BJ, van Royen-Kerkhof A, de Jager W. Correlation of CXCL10, tumor necrosis factor receptor type II, and galectin 9 with disease activity in juvenile dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:2281–9.

McHugh NJ, Tansley SL. Autoantibodies in myositis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2018;14:290–302.

Aggarwal R, Oddis CV, Goudeau D, Koontz D, Qi Z, Reed AM, et al. Autoantibody levels in myositis patients correlate with clinical response during B cell depletion with rituximab. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55:991–9.

Ishizuka M, Watanabe R, Ishii T, Machiyama T, Akita K, Fujita Y, et al. Long-term follow-up of 124 patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis: statistical analysis of prognostic factors. Mod Rheumatol. 2016;26:115–20.

Dalakas MC. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Lancet. 2003;362:971–82.

Nozaki K, Pestronk A. High aldolase with normal creatine kinase in serum predicts a myopathy with perimysial pathology. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:904–8.

Rider LG, Giannini EH, Harris-Love M, Joe G, Isenberg D, Pilkington C, International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group, et al. Defining clinical improvement in adult and juvenile myositis. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:603–17.

Oddis CV, Rider LG, Reed AM, Ruperto N, Brunner HI, Koneru B, International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group, et al. International consensus guidelines for trials of therapies in the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2607–15.

Aggarwal R, Rider L, Ruperto N, Bayat N, Erman B, Feldman BM, et al. 2016 American College of Rheumatology (ACR)- European league against rheumatism (EULAR) criteria for minimal, moderate and major clinical response for adult dermatomyositis and polymyositis: an international myositis assessment and clinical studies group/ pediatric rheumatology international trials organization collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:792–801.

Abdul-Aziz R, Yu CY, Adler B, Bout-Tabaku S, Lintner KE, Moore-Clingenpeel M, et al. Muscle MRI at the time of questionable disease flares in juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM). Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2017;15:25.

Yao L, Yip AL, Shrader JA, Mesdaghinia S, Volochayev R, Jansen AV, et al. Magnetic resonance measurement of muscle T2, fat-corrected T2 and fat fraction in the assessment of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55:441–9.

Day J, Patel S, Limaye V. The role of magnetic resonance imaging techniques in evaluation and management of the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2017;46:642–9.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Brazilian Society of Rheumatology.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact author for data requests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to write and review the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

de Souza, F.H.C., de Araújo, D.B., Vilela, V.S. et al. Guidelines of the Brazilian Society of Rheumatology for the treatment of systemic autoimmune myopathies. Adv Rheumatol 59, 6 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42358-019-0048-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42358-019-0048-x