Abstract

Background

As widely known, an intrauterine device (IUD) is a small, typically T-shaped contraceptive device that offers long-term reversible birth control. However, neglecting to remove the IUD can lead to severe complications. This case report showcases an exceptional instance that underscores the potential risks associated with retention of an IUD.

Case presentation

This case report documents a 40-year-old female who failed to remove her intrauterine device for eight years. Upon her visit to our clinic, she presented with increased urinary frequency, burning micturition, dysuria, and discomfort while emptying her bladder. Medical review consisting of ultrasound (KUB) and X-ray pelvis revealed the intrauterine device had migrated and was encrusted with a stone. We used Holmium laser lithotripsy to break down the stone, before using cystoscope to manually remove the intrauterine device. She made a rapid recovery without any complications.

Conclusions

In order to raise awareness about forgotten or misplaced IUDs and their complications, we are presenting a case of complete intravesical IUD migration at our clinic. This serves as an educational opportunity to shed light on this uncommon occurrence and emphasize the importance of timely removal and follow-up in patients using intrauterine devices (IUDs).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

IUDs are a popular form of contraception used worldwide. They are known for their low incidence of complications, most of which are non-severe. Although uterine perforation is considered a serious complication, instances of IUD penetration into the bladder following such perforation are extremely rare (Cheung and Rezai 2018).

We present a case of intrauterine device (IUD) migration to the bladder and provide a comprehensive review of existing literature on this matter.

Case presentation

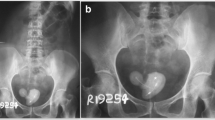

In November 2022, a 40-year-old woman visited the Urology Outpatient Department with complaints of worsening recurrent urinary tract infections. She experienced symptoms such as urgency, increased urinary frequency, burning during urination, pelvic pain, and discomfort in the lower abdomen. The patient had previously been diagnosed with recurrent urinary infections by her family physician. However, due to the persistent nature of her UTIs, further investigations were conducted. Urine culture and sensitivity tests revealed that the organisms responsible for her most recent UTIs were Enterococcus spp. and E. coli. During the evaluation process, an X-ray of the pelvis was recommended to investigate the source of the pelvic pain. The X-ray revealed an opacity measuring 3–4 cm around a T-shaped foreign object (Fig. 1). To confirm this finding, an ultrasound was performed, which verified a stone in the bladder. The patient then mentioned that she had failed to remove an IUD inserted approximately 8 years back. In the pelvic ultrasound examination, no IUD was detected. The urine culture conducted at this time showed no growth, and blood tests confirmed normal renal function. The patient had no significant medical or surgical history, and there was no previous history of urolithiasis. No imaging scans had been done since the insertion of the IUD. The cystoscopy under anesthesia revealed a heavily calcified, free-floating intravesical calculus located over the T-shaped IUD (Fig. 2). The patient underwent Holmium laser Lithotripsy to fragment the stone and remove the T-shaped coil (Figs. 3, 4). Following the procedure, contrast was introduced into the bladder to ensure there was no leakage. No extravasation of contrast or fistulous tract was observed. Foley catheter was kept in place post-operatively for two days. The patient demonstrated complete recovery, with the recurrence of urinary tract infections resolving and remaining free from symptoms during subsequent follow-up visits.

Discussion

The intra-uterine contraceptive device (IUCD) is widely recognized as an effective and reliable method of long-term contraception for family planning purposes. However, it is important to acknowledge that complications can arise from the use of these devices, including spontaneous or septic abortion, migration into nearby structures, bowel perforation, and the formation of vesicouterine fistulas (Bakri et al. 2023). Although the occurrence of IUCD erosion into adjacent structures is exceptionally rare, instances have been reported where these devices have migrated into the peritoneum, colon, omentum, bladder, and appendix (Koh 2023). Moreover, there have been documented cases where various foreign objects, such as surgical appliances, urethral dilators, wires, and coffee spoon handles have been mistakenly introduced into the body. Typically, these objects find their way through the urethra, often due to self-introduction or during transurethral surgical procedures. In rare instances, they may be inadvertently placed during an open surgical procedure or migrate from neighboring anatomical structures (Tosun et al. 2010; Rasekhjahromi et al. 2020). The severity of complications arising from a displaced IUD depends on its location. The potential medical conditions associated with such displacements are extensive and can lead to a variety of health complications, including appendicitis, sepsis, ectopic pregnancy, septic abortion, pelvic abscess, acute bowel obstruction, obstructive nephropathy, and even pulmonary embolism. In this particular case, the displacement did not cause any symptoms directly, making it difficult to determine when exactly the migration occurred (Nouioui et al. 2020; Beckley et al. 2011; Ismail 2008). According to the literature, IUD migration can occur to the peritoneum, omentum, bladder (intravesical), rectosigmoid, adnexa, appendix, colon, small bowel, and even the iliac vein (Wijaya et al. 2022; Markovitch et al. 2002; Beckley et al. 2011). The time between IUD insertion and the onset of symptoms can vary significantly, ranging from six months to sixteen years before patients present with acute symptoms. In this case, the patient experienced recurrent urinary tract infections and suprapubic pain 8 years after the insertion of the IUD. Although the exact timing of the IUD migration remains unknown, it is likely related to the development of her UTIs (Beckley et al. 2011; Tosun et al. 2010; Dietrick et al. 1992). The precise mechanism by which perforation of uterus occurs due to IUD migration or incorrect placement is not fully understood. However, several risk factors have been identified as potential contributors to uterine perforation (Ismail 2008). Different treatment options are available for intravesical IUDs, depending on the individual circumstances. When the IUD is entirely present within the bladder, either with small stones or not, it can be removed using through urethra or from suprapubic route by cystoscope. In situations where there are larger stones present or if the IUD has invaded the bladder wall, laparoscopic or open surgery might be required to safely remove the coil. (Chama et al. 2023; Zhang et al. 2020). Successful and complete extraction of migrated IUDs in the bladder has been achieved using a combination of various endoscopes, with an average operative time of 56 min (Akhtar et al. 2021). In our procedure, we employed Holmium laser lithotripsy to break down the stone, resulting in a reduced operative time of 30 min, including the removal of the T-shaped coil. With the increasing use of IUDs as a contraception method, the incidence of IUD migration is believed to be on the rise.

Conclusions

It is important to thoroughly investigate recurring urinary tract infections in females who are using long-term contraception, specifically taking into consideration the possibility of IUD migration. It is crucial to include the patient's gynecological history in urological history. The management of migrated IUDs remains a topic of debate. However, if migration is detected, removal of the IUD is necessary.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- IUD:

-

Intrauterine contraceptive device

References

Akhtar OS, Rasool S, Nazir SS (2021) Migrated intravesical intrauterine contraceptive devices: a case series and a suggested algorithm for management. Cureus 13(1):e12987. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.12987.PMID:33654641;PMCID:PMC7916746

Bakri S, Azis A, Nusraya A, Putra MZ, Natsir AS, Pattimura MI (2023) Intrauterine device (IUD) migration into the bladder with stone formation: a case report. Urol Case Rep 1(49):102439

Beckley I, Abrahamb R, Rogawski K (2011) Intravesical Migration of an Intrauterine Contraceptive Device. Department of Urology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Huddersfield Royal Infirmar

Chama O, Mhammedi NA, Benabdelhak O (2023) Intravesical migration of an intrauterine contraceptive device secondarily calcified: a case report. Urol Nephrol Open Access J 11(1):27–28

Cheung ML, Rezai S (2018) Retained intrauterine device (IUD): triple case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2018:9362962

Dietrick DD, Issa MM, Kabalin JN, Bassett JB (1992) Intravesical migration of intrauterine device. J Urol 147(1):132–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37159-8

Ismail MAA (2008) Perforating intravesical intrauterine devices: diagnosis and treatment. UroToday Home, vol 1(5)

Koh AS (2023) Neglected intrauterine device migration complications. Women’s Health Rep 4(1):11–18

Markovitch O, Klein Z, Gidoni Y, Holzinger M, Beyth Y (2002) Extrauterine mislocated IUD: is surgical removal mandatory? Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sapir Medical Center, Kfar-Saba, affiliated with Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel-Aviv University, Ramat-Aviv, Israel 66(2):105–8

Nouioui MA, Taktak T, Mokadem S, Mediouni H, Khiari R, Ghozzi S (2020) A mislocated intrauterine device migrating to the urinary bladder: an uncommon complication leading to stone formation. Case Rep Urol 7:2020

Rasekhjahromi A, Chitsazi Z, Khlili A, Babaarabi ZZ (2020) Complications associated with intravesical migration of an intrauterine device. Obstet Gynecol Sci 63(5):675–678

Tosun M, Celik H, Yavuz E, Çetinkaya MB (2010) Intravesical migration of an intrauterine device detected in a pregnant woman. Can Urol Assoc J 4(5):E141–E143

Wijaya MP, Seputra KP, Daryanto B, Budaya TN (2022) Calculus formation in bladder from migrated intrauterine devices. J Kedokt Brawijaya 4:138–141

Zhang NN, Zuo N, Sun TS, Yang Q (2020) An effective method combining various endoscopes in the treatment of intravesical migrated intrauterine device. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 27(3):582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2019.07.024

Acknowledgements

Midcity Hospital Lahore Pakistan.

Funding

Not funded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FH, MA. MMA, AA All authors contributed equally. All authors involved in the research has reviewed the manuscript and given their approval for its publications.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval not applicable. We obtained written informed consent from the patient to publish.

Consent for publication

We obtained consent from the patient to publish their information in this case report.

Competing interests

No conflicts of interest regarding the research, authorship, or publication of this case report.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hameed, F., Anwaar, A., Anwar, M. et al. Vesical stone formation caused by a forgotten and migrated intrauterine contraceptive device: a case report with literature review. Bull Natl Res Cent 48, 36 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-024-01193-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-024-01193-3