Abstract

Background

Highly active antiretroviral drug therapy (HAART) remains the only officially available option for the management of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection at designated medical institutions in Nigeria. This study investigated the impact of HAART on glucose level, lipid profile, blood parameters and growth indices of HIV-infected patients at a tertiary health center in Nigeria. Biochemical and hematologic indices were determined in HIV patients on HAART at the Federal Medical Centre (FMC), Owo, Nigeria. Plasma glucose and lipid profile were biochemically determined in 140 age-matched individuals divided into three groups: Group I (n = 70) comprised seventy clinically diagnosed and laboratory-confirmed HIV-positive patients before receiving HAART (HIV-positive group); Group II (n = 70) comprised the same set of HIV-positive patients who had received HAART for 1 year (HAART group); and Group III (n = 70) comprised healthy controlled subjects who proved HIV-negative (HIV-negative group). Growth indices were used to monitor the changes in immune response (white blood cell counts) of the HIV-infected patients.

Results

HAART ameliorated reduced body mass index and disorder in white blood cell counts but not dyslipidemia and hyperglycemia caused by HIV infection. Results confirmed the effectiveness of HAART in preventing the development of full-blown acquired immune deficiency syndrome in HIV-positive patients. However, increases in cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol levels coupled with increased atherogenic index occasioned by HAART portend the risk of cardiovascular disease.

Conclusions

HIV infection has a negative impact on the anthropometric, hematologic and biochemical indices of patients. Although HAART is helpful to improve anthropometric and hematological indicators, there is a need to improve drug regimens to reduce or eliminate undesirable metabolic complications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is the etiologic agent for the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) which weakens the immune system paving the way for opportunistic infections which are the main cause of death in HIV-infected patients (Ryu and Ryu 2017). The classification of HIV and its mode of expression after infecting a host have been adequately reported in the literature (Harrington and Carpenter 2000; Melhuish and Lewthwaite 2018). Data on the worldwide and regional prevalence of HIV have also been published (Etukumana et al. 2011; Adeyemo et al. 2014; Murray et al. 2014, 2018; Fact sheet 2019). The prevalence of HIV—1 patients, HIV—2 patients, and patients with coinfection by both viruses in Nigeria was 97.5%, 2.4%, and 0.1%, respectively (Harrington and Carpenter 2000).

The onset of AIDS marks the end of a dynamic struggle between the virus and the immune system when the virus breaks through the host’s immune defenses. Knowledge of the means by which HIV gains access to CD4+ cells and its replication mechanism led to the development of several agents to control the disease. At present, the combination therapy known as Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) is the gold standard in the management of AIDS. The effectiveness of HAART in reducing mortality and morbidity from HIV infection was noted decades ago (Palella et al. 1998). HAART reduces the viral load, at times to undetectable levels by current blood testing techniques, by targeting susceptible points in the life cycle of HIV (Roy et al. 2002).

High-density lipoprotein (HDL) clears cholesterol from the arteries and delivers it to the liver and apolipoprotein A (ApoA) is the protein component of HDL. Low-density lipoproteins (LDL) carry cholesterol and fat throughout the body through the arteries. Apolipoprotein B (ApoB) is the major protein component of chylomicrons, very LDLs (VLDLs), intermediate-density lipoproteins, lipoprotein(a) and LDLs, and it carries fat and cholesterol through the body. ApoB particles are potentially atherogenic particles and ApoA-I particles are non-atherogenic particles. If an ApoB particle enters the vessel wall, its moiety attaches (fixes) to arterial wall proteoglycans, and the surface phospholipids are subject to modification by reactive oxygen species, and the proteins by glycation from glucose. The oxidized phospholipids are subject to further lipolysis by lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 and the hydrolytic products (oxidized fatty acids and lysophosphatidylcholine), create endothelial dysfunction and recruitment of macrophages. Quantitating atherogenic lipoproteins is used to predict the risk of cardiovascular diseases.

Until recently, there is no cure for HIV infection, and antiretroviral therapy remains the only widely acknowledged means of managing HIV/AIDS. Despite these facts, it was speculated that in Nigeria, up to 80% of people do not have access to treatment. However, coordinated efforts by Government and non-governmental agencies at improving this scenario are being implemented with encouraging results (Fact Sheet, Anti-Retroviral Therapy 2016). This study was carried out at the Federal Medical Center (FMC), Owo, located in Owo Local Government Area, Ondo State, Nigeria. At the time the research was carried out, FMC was the only hospital administering HAART in the area. The hospital provides healthcare services at the tertiary level to people within its catchment. Screening tests and therapy are carried out at the center. The use of HAART has been an effective way of management of HIV infection at this center. Since antiretroviral therapy is still the only widely acknowledged means for managing HIV/AIDS, there is a need to effectively monitor the progress or physiological improvement or any side effect of antiretroviral treatment. We, therefore, conducted a study to evaluate the biochemical, hematological, atherogenic, and anthropometric indices of HIV patients attending FMC, Owo, Nigeria, to determine areas needing improvement in HIV-positive individuals on HAART in comparison with healthy control subjects.

Methods

Chemicals

The HAART drugs employed included zidovudine, lamivudine, nevirapine, tenofovir and efavirenz in the appropriate combinations. Kits for the evaluation of total cholesterol, triglyceride, HDL-cholesterol and glucose levels were obtained from Randox Laboratories Limited (Antrim, UK).

Study groups

Equipment and facilities used for the study were obtained at the hospital and used according to standard procedures. A total of 140 age-matched individuals were used for this study. Group I (n = 70) comprised seventy clinically diagnosed and laboratory-confirmed HIV-positive patients before receiving HAART (HIV-positive group); Group II (n = 70) comprised the same set of HIV-positive patients who had received HAART for 1 year (HAART group); and Group III (n = 70) comprised healthy controlled subjects who proved HIV-negative (HIV-negative group). Collectively, a total of 210 samples were collected from subjects used for the study. Informed consent was obtained from patients. Patients were of Yoruba ethnicity, educated, and were a mixture of both males and females between the age of 16 and 65 years. Weight, height and body mass index (BMI) were used to monitor changes in the health profile of the patients in the HIV-positive and HAART groups. Measurements were done at the beginning of the study, and the age brackets at the initial period were maintained to avoid confusion and errors.

Criteria of case selection

Inclusion criteria: Individuals (≥ 16 years old) that were HIV-positive at the time of HAART administration and those on HAART for at least 6 months that gave their consent were included in the study. Exclusion criteria: Those who were severely sick due to other medical conditions, those diagnosed as having hematological diseases, subjects with malignancy demanding cytotoxic chemotherapy or radiation therapy, pregnant women and those who did not give their consent were excluded from the study.

Sample collection, hematological and biochemical estimation

Peripheral blood was drawn by venipuncture into a vacutainer tube containing EDTA anticoagulant to prevent clotting of blood and labeled with the participant's ID number. The blood was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 15 min at room temperature to separate the blood into two layers. The upper layer (plasma) was used for biochemical analyses.

Determination of hematological indices

White blood cell counting was performed as previously described (Gordon et al. 1978). Differential leucocyte counting was carried out according to the previous method (Wintrobe et al. 1992).

Determination of biochemical indices

Levels of cholesterol, triglycerides (TG), high-density lipoproteins-cholesterol (HDL-c) and glucose in plasma were determined with kits obtained from Randox Laboratories Limited (Antrim, UK) following the instructions of the manufacturer. Low-density lipoproteins-cholesterol (LDL-c) concentration was estimated according to Friedwald et al. (1972). Atherogenic index of plasma (AIP) was estimated according to Onat et al. (2010).

Determination of anthropometric indices

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from patients’ measured weight and height (kg/m2). The weight status of patients was determined based on the World Health Organization standard BMI cutoff points. Underweight was defined as a BMI < 18.5, normal weight as a BMI between 18.5 and 24.9, and overweight or obese as a BMI ≥ 25 (WHO 2019).

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was carried out using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey–Kramer multiple comparisons test. The significance level was set at p < 0.05. All the statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Total leukocyte count and lymphocyte counts were significantly high in the HIV-negative group compared with the HAART group while the HIV-positive group has the lowest counts. Furthermore, the neutrophil and monocyte counts which signify the number of cells that fight infections were significantly high in the HIV-positive group compared with the HAART group and least in the HIV-negative group (p < 0.05) (Table 1). However, monocyte counts for the HIV-negative group and the HAART group were not significantly different (p > 0.05). The eosinophil and basophil counts were not significantly different in the three groups (p > 0.05). Furthermore, the neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio for the HIV-positive group was > 50% higher than the values for HIV-negative and HAART groups, which were not significantly different (Fig. 1).

Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio of age-matched HIV-positive patients, HIV patients after a year of HAART and HIV-negative subjects. ***p < 0.001 versus HIV-positive; **p < 0.01 versus HIV-negative. HIV+ve HIV-positive group, HAART HIV-positive patients on HAART, HIV-negative HIV-negative group. The neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio was skewed by HIV infection, but the imbalance was ameliorated in patients on HAART

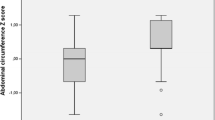

The plasma lipid profile presented in Table 2 showed that HIV-positive patients that were treated with HAART for 1 year had increased lipid levels, that is, the levels of cholesterol, triglyceride, HDL-c, and LDL-c increased compared with untreated HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients. However, the cholesterol, triglyceride, HDL-c, and LDL-c levels of HIV-negative patients were significantly higher than their levels in untreated HIV-negative patients. The same trend of the result was observed in the level of glucose. However, the cholesterol/HDL ratio (Fig. 2a) and LDL/HDL ratio (Fig. 2b) for the HAART group were significantly higher than the values for HIV-positive and HIV-negative groups, which were not significantly different. Figure 2c shows the AIP across all age-groups in the study groups. The AIP for the HAART group was higher than the values for HIV-positive and HIV-negative groups (p < 0.001). This perturbation in plasma lipid profile and HAART-treated patients may predispose these patients to cardiovascular complications if not managed properly.

a Cholesterol/HDL-c ratio of age-matched HIV-positive patients, HIV patients after a year on HAART, and HIV-negative subjects. ***p < 0.001 versus HIV-positive and HIV-negative; #p > 0.05 versus HIV-positive. Cholesterol/HDL-c ratio in HIV-positive patients was not significantly different from values for normal subjects but the ratio was skewed in HIV-positive patients on HAART; b LDL/HDL-c ratio of age-matched HIV-positive patients, HIV patients after a year of HAART, and HIV-negative subjects. ***p < 0.001 versus HIV-positive and HIV-negative; #p > 0.05 versus HIV-positive. LDL/HDL-c ratios were similar in HIV-positive patients and normal subjects but skewed in HIV-positive patients on HAART; c Atherogenic index of plasma (AIP) of HIV-positive patients, HIV patients after a year of HAART, and HIV-negative subjects. Each value is significantly different from the others (p < 0.05). Values indicated a lower cardiovascular risk for HIV-positive and HIV-negative groups

The BMI of the HAART group and the HIV-negative group were not significantly different, but the BMI value for the HIV-positive group was significantly lower due to the weight loss that followed HIV infection (Table 3). Results indicated that HIV status but not age may be responsible for observed differences in values obtained in all groups.

Table 4 presents the relationships between pairs of selected parameters in terms of their Pearson correlation coefficients (r). The table reveals that HIV infection and HAART treatment caused a significant deviation from the normal relationship between indices in healthy individuals that are HIV-negative.

Discussion

The use of HAART led to a dramatic decrease in morbidity and mortality among patients who are HIV-positive. HAART substantially improves the health profile of patients engendering increased survival rates of HIV-infected individuals in agreement with previous findings (Crabtree-Ramírez et al. 2010; Ballocca et al. 2016). In the present study, the results of hematological determinations showed that HIV-positive patients not undergoing HAART stand the risk of opportunistic infections which may further compromise their immunity and chance of survival. White blood cells (leukocytes) consist of neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes cells which participate in adaptive immune responses.

The reported normal number of WBCs in the blood is 4500–11,000 per microliter (Lichtman et al. 2017). In this study, HAART treatment elevated the decreased count observed in HIV-positive patients, According to the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, the percentages of white blood cells in healthy people are as follows: 54–62% neutrophils, 25–30% lymphocytes, and 0–9% monocytes (Lichtman et al. 2017). The result of the total white blood cell count in the HAART group showed that the leucopenia occasioned by HIV infection was ameliorated by HAART. Neutrophils and monocytes which are important in inflammatory response were significantly increased in the HIV-positive group while the antibody-forming lymphocytes were reduced. In this study, there was no significant difference in the percent eosinophil and percent basophil between the three groups. This is in line with the reports that found no distinct pattern of variation in eosinophil count of HIV-positive patients (Kaewketthong et al. 2013) and that basophil count remains fairly stable during HIV progression (Jiang et al. 2015; Marone et al. 2016). In general, the blood differential tests revealed that HIV-positive patients on HAART at FMC, Owo, Nigeria showed a positive response to treatment.

Dyslipidemia is a syndrome that involves increased levels of cholesterol and triglycerides in the blood (Barzegar-Amini et al. 2019; Simental-Mendía and Guerrero-Romero 2019) which was observed in the HAART group. In addition, the fasting plasma sugar (FPG) level (a marker for determining the level of glucose in the bloodstream of diabetic patients) was least in the HIV+ group and highest in the HAART group. This shows that HAART treatment led to dyslipidemia and hyperglycemia in the patients. This is in line with the well-documented reports that HIV-positive patients on antiretroviral drugs are susceptible to cardiovascular complications and diabetes (Worm et al. 2010; Moyo et al. 2013). Of note is the disproportionate increase in LDL levels compared to HDL levels in the HAART group versus the HIV-negative group. Friis-Møller et al. (2003) reported that patients who did not receive therapy had a lower incidence of cardiovascular disease than those treated. Our result corroborated this evidence. The results also demonstrated that while HIV infection alone caused abnormal lipid and glucose levels, these are exacerbated by HAART.

The anthropometric measurements indicated that while HIV-positive patients not on HAART lost much weight and their BMI values dropped below 25 kg/m2, treatment with HAART restored BMI values to control levels. Therefore, HAART had a positive effect on BMI.

Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio (N/L), cholesterol/HDL-c ratio (CHOL/HDL-c) and LDL-c/HDL-c ratio are important risk indicators for cardiovascular and other diseases. White blood cell count is one of the useful inflammatory biomarkers in clinical practice. However, even when white blood cell count is in the normal range, subtypes of white blood cells like N/L are used as inflammatory markers related to cardiovascular and other diseases like cancer and may be a predictor of mortality in all conditions (Absenger et al. 2013; Angkananard et al. 2017; Corriere et al. 2018). Neutrophils and lymphocytes are white blood cell types that respond to infection, and stress and coordinate inflammation. N/L, which is the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, can be used as an indicator of inflammation in the body. An increase in the N/L ratio could be pointing to inflammation which when coupled with an increase in lipid profile could be an indication of cardiovascular problems. Therefore, the significant increase in N/L in the HIV-positive group additionally pointed to the risk of cardiovascular complications and other diseases in AIDS. HAART had a positive effect on this ratio. Cholesterol//HDL ratio and LDL/HDL ratio are better indicators of cardiovascular risk than the isolated parameters (Millán et al. 2009). In this study, the cholesterol//HDL and LDL/HDL ratios were skewed by HAART. HAART elicited a disproportionate increase in LDL levels which occasioned an inversion of the usual relationship between LDL and HDL in healthy individuals. These observations indicated that HAART portends serious risks of cardiovascular disease. Metabolic abnormalities, including dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, diabetes, and increased inflammatory indexes, have been increasingly observed among HIV-infected patients in the current era of highly active antiretroviral therapy (Friedewald et al. 1972; Wintrobe et al. 1992). The causes of these abnormalities are complex and multifactorial, likely related in part to the effects of HIV, chronic inflammatory conditions, medication effects, e.g., of specific protease inhibitors on lipid metabolism and nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors on mitochondrial function, and changes in body composition, with relative losses in subcutaneous fat and gains in central adiposity with the institution of antiretroviral therapy. These changes may place HIV-infected patients at greater risk of cardiovascular disease. Indeed, although it has been reported that overall morbidity and mortality have decreased significantly with the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy, concern has been raised as to cardiovascular disease becoming an increasing problem for such patients, especially as they aged (Grunfeld et al. 2008; Ballocca et al. 2016; Rossano and Lin 2017).

The atherogenic index of plasma (AIP) calculated as log (TG/HDL-C) is a significant predictor of atherosclerosis and an independent predictor of coronary heart disease. It has been used as an additional index in the assessment of cardiovascular risk factors (Onat et al. 2010; Nwagha et al. 2010; Bo et al. 2018). It has been suggested that AIP values of − 0.3 to 0.1 are associated with low, 0.1–0.24 with medium and above 0.24 with high CV risk (Dobiásová 2006; Nwagha et al. 2010). The AIP values in the HAART group in this study indicated a significant potential cardiovascular risk.

The evaluated hematologic, biochemical, and anthropometric indices together with those of additional cardiovascular risk factors computed from the primary data of patients in this study demonstrated that while HIV infection alone predisposed patients to cardiovascular complications, the risk was significantly exacerbated by HAART. Reports have shown that HAART causes metabolic derangement due to the presence of protease inhibitors in the drug regimen (Hui 2003; da Cunha et al. 2015).Protease inhibitors cause excessive central fat deposition (lipodystrophy), hyperlipidemia, as well as insulin resistance. Some of the major mechanism for protease inhibitors’ side effect include the suppression of the breakdown of the nuclear form of sterol regulatory element binding proteins (nSREBP) in the liver and adipose tissues which result in increased fatty acid, and cholesterol biosynthesis, lipodystrophy, and reduced expression of leptin (Riddle et al. 2001). HIV protease inhibitors also suppress the proteasome-mediated breakdown of nascent apolipoprotein (apo) B, which results in the overproduction and secretion of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (Liang et al. 2001). The relationships between some pairs of indices in the HIV-negative group were markedly distorted by HIV infection and in other instances by HAART. For example, HIV infection disrupted correlations between CHOL/HDL-c and CHOL/LDL-c compared to the HIV-negative group while HAART disrupted the correlation between N/CHOL compared to the HIV-negative group. These observations indicated that patients on HAART at FMC, Owo, Nigeria may be at risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes.

Conclusions

This study showed that HAART was helpful to patients at FMC, Owo, Nigeria, and has a positive effect on the hematological parameters and BMI of patients. However, HAART had an adverse effect on their lipid profile and blood glucose level. This study confirmed previous reports that HIV infection on one hand and antiretroviral therapy on the other created imbalances in the biochemical profiles of patients. The role of HAART in HIV could be described as double-edged. Therefore, there is a need to step up the search for ways to improve drug regimens in order to reduce or eliminate undesirable metabolic complications. Highly active antiretroviral therapy for HIV-infected patients could be regarded as a bitter-sweet situation for now but, hopefully, this would become an all-sweet situation with the discovery of ways to eliminate the present complications accompanying HAART.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and are also available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AIDS:

-

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome

- AIP:

-

Atherogenic index of plasma

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CHOL/HDL-c:

-

Cholesterol/HDL-cholesterol ratio

- CHOL/LDL-c:

-

Cholesterol/LDL-cholesterol ratio

- FPG:

-

Fasting plasma glucose

- HAART:

-

Highly active antiretroviral drug therapy

- HDL or HDL-c:

-

High-density lipoprotein-cholesterol

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- LDL or LDL-c:

-

Low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol

- N/L:

-

Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio

- TG:

-

Triglycerides

References

Absenger G, Szkandera J, Pichler M, Stotz M, Arminger F, Weissmueller M, Schaberl-Moser R, Samonigg H, Stojakovic T, Gerger A (2013) A derived neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts clinical outcome in stage II and III colon cancer patients. Br J Cancer 109:395–400

Adeyemo BO, Gayawan E, Olusile AO, Komolafe IOO (2014) Prevalence of HIV infection among pregnant women presenting to two hospitals in Ogun state, Nigeria. HIV AIDS Rev 13:90–94

Angkananard T, Anothaisintawee T, Thakkinstian A (2017) Neutrophil lymphocyte ratio and risks of cardiovascular diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis 263:e159–e160

Ballocca F, Gili S, D’Ascenzo F, Marra WG, Cannillo M, Calcagno A, Bonora S, Flammer A, Coppola J, Moretti C, Gaita F (2016) HIV infection and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: lights and shadows in the HAART era. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 58:565–576

Barzegar-Amini M, Ghazizadeh H, Seyedi SM, Sadeghnia H, Mohammadi A, Hassanzade-Daloee M, Barati E, Kharazmi-Khorassani S, Kharazmi-Khorassani M, Mohammadi-Bajgirani M, Tavallaie S, Ferns G, Mouhebati M, Ebrahimi M, Tayefi M, Ghayour-Mobarhan M (2019) Serum vitamin E as a significant prognostic factor in patients with dyslipidemia disorders. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev 13:666–671

Bo MS, Cheah WL, Lwin S, Moe Nwe T, Win TT, Aung M (2018) Understanding the relationship between atherogenic index of plasma and cardiovascular disease risk factors among staff of an University in Malaysia. J Nutr Metab 2018:7027624

Corriere T, Di Marca S, Cataudella E, Pulvirenti A, Alaimo S, Stancanelli B, Malatino L (2018) Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is a strong predictor of atherosclerotic carotid plaques in older adults. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 28:23–27

Crabtree-Ramírez B, Villasís-Keever A, Galindo-Fraga A, del Rio C, Sierra-Madero J (2010) Effectiveness of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) among HIV-infected patients in Mexico. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir 26:373–378

da Cunha J, Maselli LM, Stern AC, Spada C, Bydlowski SP (2015) Impact of antiretroviral therapy on lipid metabolism of human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients: old and new drugs. World J Virol 4(2):56–77. https://doi.org/10.5501/wjv.v4.i2.56

Dobiásová M (2006) AIP–atherogenic index of plasma as a significant predictor of cardiovascular risk: from research to practice. Vnitr Lek 52:64–71

Etukumana EA, Thacher TD, Sagay AS (2011) Obstetrics risk of HIV infection among antenatal women in a rural Nigerian hospital. Niger Med J 52:24–27

Fact Sheet, Anti-retroviral Therapy (ART) (2016)—NACA Nigeria Available online: https://naca.gov.ng/fact-sheet-anti-retroviral-therapy-art-2016/. Accessed 26 Jan 2019

2018 Fact sheet (2019) Global HIV & AIDS statistics, UNAIDS AIDSinfo. https://aidsinfo.unaids.org. Accessed Nov 2020.

Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS (1972) Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem 18:499–502

Friis-Møller N, Sabin CA, Weber R, d’Arminio Monforte A, El-Sadr WM, Reiss P, Thiébaut R, Morfeldt L, De Wit S, Pradier C et al (2003) Combination antiretroviral therapy and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 349:1993–2003

Gordon C, Penington DG, Rush B, Castaldi P (eds) (1978) Clinical hematology in medical practice. Blackwell Scientific, Chicago

Grunfeld C, Kotler DP, Arnett DK, Falutz JM, Haffner SM, Hruz P, Masur H, Meigs JB, Mulligan K, Reiss P, Samaras K, Working Group 1 (2008) Contribution of metabolic and anthropometric abnormalities to cardiovascular disease risk factors. Circulation 118(2):e20–e28

Harrington M, Carpenter CC (2000) Hit HIV-1 hard, but only when necessary. Lancet 355:2147–2152

Hui DY (2003) Effects of HIV protease inhibitor therapy on lipid metabolism. Prog Lipid Res 42(2):81–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0163-7827(02)00046-2

Jiang AP, Jiang JF, Guo MG, Jin YM, Li YY, Wang JH (2015) Human blood-circulating basophils capture HIV-1 and mediate viral trans-infection of CD4+ T cells. J Virol 89(15):8050–8062

Kaewketthong P, Doydee J, Thawenuch S, Thuayset T, Khupulsup K, Butthep P (2013) Increased eosinophil levels in HIV-infected patients with high CD4/CD8 ratio study from 564 patients in Ramathibodi Hospital. Asian Arch Pathol 9(2):64–71

Liang JS, Distler O, Cooper DA, Jamil H, Deckelbaum RJ, Ginsberg HN, Sturley SL (2001) HIV protease inhibitors protect apolipoprotein B from degradation by the proteasome: a potential mechanism for protease inhibitor-induced hyperlipidemia. Nat Med 7(12):1327–1331

Lichtman MA, Kaushansky K, Prchal JT, Levi MM, Burns LJ, Armitage JO (2017) Table of normal values. In: Williams A (ed) Manual of Hematology, 9th edn. McGraw Hill, New York

Marone G, Varricchi G, Loffredo S, Galdiero MR, Rivellese F, de Paulis A (2016) Are basophils and mast cells masters in HIV infection? Int Arch Allergy Immunol 171(3–4):158–165

Melhuish A, Lewthwaite P (2018) Natural history of HIV and AIDS. Medicine (baltimore) 46:356–361

Millán J, Pintó X, Muñoz A, Zúñiga M, Rubiés-Prat J, Pallardo LF, Masana L, Mangas A, Hernández-Mijares A, González-Santos P, Ascaso JF, Pedro-Botet J (2009) Lipoprotein ratios: physiological significance and clinical usefulness in cardiovascular prevention. Vasc Health Risk Manag 5:757–765

Moyo D, Tanthuma G, Mushisha O, Kwadiba G, Chikuse F, Cary MS, Steenhoff AP, Reid MJ (2013) Diabetes mellitus in HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy. S Afr Med J 104(1):37–39

Murray CJL, Ortblad KF, Guinovart C, Lim SS, Wolock TM, Roberts DA et al (2014) Global, regional, and national incidence and mortality for HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 384:1005–1070

Nwagha UI, Ikekpeazu EJ, Ejezie FE, Neboh EE, Maduka IC (2010) Atherogenic index of plasma as useful predictor of cardiovascular risk among postmenopausal women in Enugu, Nigeria. Afr Health Sci 10:248–252

Onat A, Can G, Kaya H, Hergenҫ G (2010) Atherogenic index of plasma (log10 triglyceride/high-density lipoprotein−cholesterol) predicts high blood pressure, diabetes, and vascular events. J Clin Lipidol 4:89–98

Palella FJ, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, Loveless MO, Fuhrer J, Satten GA, Aschman DJ, Holmberg SD (1998) Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. N Engl J Med 338:853–860

Riddle TM, Kuhel DG, Woollett LA, Fichtenbaum CJ, Hui DY (2001) HIV protease inhibitor induces fatty acid and sterol biosynthesis in liver and adipose tissues due to the accumulation of activated sterol regulatory element-binding proteins in the nucleus. J Biol Chem 276(40):37514–37519

Rossano JW, Lin KY (2017) HAART for kids’ hearts: the long view. J Am Coll Cardiol 70:2248–2249

Roy J, Paquette JS, Fortin JF, Tremblay MJ (2002) The immunosuppressant rapamycin represses human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:3447–3455

Ryu WS, Ryu WS (2017) HIV and AIDS. Mol Virol Hum Pathog Viruses 2017:305–317

Simental-Mendía LE, Guerrero-Romero F (2019) Effect of resveratrol supplementation on lipid profile in subjects with dyslipidemia: a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Nutrition 58:7–10

Wintrobe MM, Lee RG, Bithell TC, Athens JW, Foerster J (eds) (1992) Clinical hematology. Lea and Febiger, Philadephia

World Health Organisation (2019) Mean body mass index (BMI), https://www.who.int/gho/ncd/risk_factors/bmi_text/en/. Accessed 26 Jan 2019

Worm SW, Sabin C, Weber R, Reiss P, El-Sadr W, Dabis F, De Wit S, Law M, Monforte AD, Friis-Møller N et al (2010) Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with HIV infection exposed to specific individual antiretroviral drugs from the 3 major drug classes: the data collection on adverse events of anti-HIV drugs (D: A: D) study. J Infect Dis 201:318–330

Acknowledgements

We thank the Medical Director, FMC, Owo, Nigeria, at the time the study was conducted and Dr. O. A. Omotosho for his support and for making facilities available for the work. We thank the HOD, Pathology Department, Dr. B. Paul-Odo, and members of the staff of the department for their cooperation and assistance during the research. We also thank the patients for their cooperation.

Funding

This research is not supported by any for- or not-for-profit organization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SEA, AIA and AAA conceptualized the research; ACA, AIA, MTO and AAA supervised and provided the resources for the conduct of the research; SEA and AIA conducted the research and carried out the bench work; SEA, ACA, IOS and BKA analyzed the data; SEA, ACA, IOS, BKA, MTO, AIA and AAA interpreted the research; SEA, IOS, BKA and ACA wrote the manuscript; IOS, ACA, and AAA edited and revised the manuscript. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and have read and approved the submission of the manuscript for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Health Research Ethics Committee of the Federal Medical Centre (FMC), Owo, Nigeria, and conformed to the principles of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and guidelines on Good Clinical Practice. Equipment and facilities used for the study were obtained at the hospital and used according to standard procedures. Informed consent was obtained from patients.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ademuyiwa, S.E.A., Saliu, I.O., Akinola, B.K. et al. Impact of highly active antiretroviral drug therapy (HAART) on biochemical, hematologic, atherogenic and anthropometric profiles of human immunodeficiency virus patients at a tertiary hospital in Owo, Nigeria. Bull Natl Res Cent 46, 263 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-022-00953-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-022-00953-3