Abstract

Background

Entomopathogenic nematodes (EPNs) have the potential to supersede larvicidal activity for the management of various insect pests.

Result

Lab experiments were conducted to test the pathogenicity of 2 EPNs local species; Steinernema feltiae and Heterorhabditis bacteriophora at different (IJs/cm2) concentrations against the cabbage butterfly, Pieris brassicae (L.). The native isolate was obtained from soil samples, collected from Rajgarh, Hamachi Pradesh, India. Petri dish bioassay used the EPNs species (S. feltiae HR1 and H. bacteriophora HR2) at the concentrations (0, 10, 20, 40, 80, 160 IJs/cm2). Based on the pathogenicity of the strains, only 2 isolates effectively showed larvicidal activity. The highest (%) (72.08 and 67.42%), at the 2nd instar larval mortality was recorded in the treatments with H. bacteriophora and S. feltiae at160 IJs/cm2, respectively. At the 4th instar larvae, respective larval mortality (85.38, 69.50%) was recorded in treatment with H. bacteriophora, and S. feltiae, respectively, at160 IJs/cm2. In case of pupae, the mortality rates were (62.12, 58.58%) for H. bacteriophora and S. feltiae, respectively, at 160 IJs/cm2; (74 and 12%) for both the tested EPNs, respectively, at 80 IJs/cm2. Percent of P. brassicae larval mortality treated with the tested EPN isolates was significantly higher than the untreated control. Results revealed that the percent of larval mortality significantly increased with the increase in time periods, being maximum at 72 h. S. feltiae and H. bacteriophora, strains showed potent larvicidal activity at low concentration even at 48 and 72 h of exposure.

Conclusion

This study revealed that the local strains of EPNs (S. feltiae HR1 and H. bacteriophora HR2) were found as a biocontrol agent against P. brassicae.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cabbage butterfly, Pieris brassicae (L.) (Lepidoptera: Pieridae), is one of the major limiting factors of cabbage production in the Himalayas, causing severe losses to the crop by larval feeding on leaves (Mazurkiewicz et al. 2017). Chemical insecticides have been a general practice used by cabbage growers for the management of P. brassicae in the Himalayas but the adverse effect of chemicals on the environment such as groundwater contamination, pesticide resistance, toxicity hazards and destruction of biodiversity of useful natural enemies demand an effective alternative method of crop insect pest management that should be eco-friendly and safe for non-target organisms. Entomopathogenic nematodes (EPNs) that belong to families, Steinernematidae and Heterorhabditidae are lethal parasites of insect pests, safe to humans, other vertebrates, non-target organisms, easy to apply, and cause no hazardous effect on the environment (Abbas et al. 2021). Besides, they are compatible with many chemical insecticides (Laznik and Trdan 2014).

Entomopathogenic nematodes (EPNs) that belong to the families Heterorhabditidae and Steinernematidae are soil-inhabiting organisms that are obligate insect parasites in nature (Kaya and Gaugler 1993). These nematodes have evolved a mutualistic association with bacteria in the genera Photorhabdus is associated with Heterorhabditis spp., is carried in the intestine of infective juveniles (IJs) (Arthurs et al. 2004). Xenorhabdus is connected with Steinernema spp. and confined to a specific vesicle within the intestine of the IJs. Nematodes locate their potential host by following insect cues (Lewis et al. 2006). After IJs locate a host, they infect it through an orifice such as the mouth, anus, or spiracles or by penetrating the cuticle (particularly in Heterorhabditis spp.). Once IJs enter the host, they shed their outer cuticle (Sicard et al. 2004) and begin ingesting hemolymph, which triggers the release of symbionts by defecation (in Steinernema spp.) or regurgitation (in Heterorhabditis spp.) (Grewal et al. 2005). The nematode–bacteria complex kills the host within 24–48 h through septicemia or toxaemia (Forst and Clarke 2002). Bacteria recolonize the nematodes, which emerge as IJs from the depleted insect cadaver in search of fresh hosts (Poinar 1990).

More than 100 species of EPNs have been identified globally in which approximately 80% are steinernematid and 13% of these species have been commercialized (Abbas et al. 2021). EPNs have been broadly used in the biological control of a variety of economically important pests occupying different habitats (Grewal et al. 2005). However, EPN formulation to retard desiccation or the addition of adjuvants to increase leaf coverage and persistence of the IJs has enhanced the use of EPNs against foliar pests (Head et al. 2004).

The objective of the present study was to provide fundamental information necessary for the utilization of indigenously isolated EPNs as a biological control agent. The study dealt with 2 nematode species such as S. feltiae and H. bacteriophora (Poinar) and their pathogenicity against P. brassicae under laboratory conditions.

Methods

Rearing of Pieris brassicae

Pieris brassicae (L.) eggs, natural infestation, were collected from open fields represent the mid-hill zone of western Himalayas, Department of Entomology Research farm, UHF. The eggs were found in clusters on the lower sides of the leaves of few plants. Collected eggs was brought to the laboratory and placed in a B.O.D (Biological oxygen demand) incubator calibrated at 25 ± 1 °C coupled with 65 + 5% relative humidity and the photoperiod of 12 h L:12 h D. The eggs were maintained under Nematology laboratory at the Department of Entomology, UHF Nauni, Solan, HP, India. After calculating the percent of hatching from eggs, one hundred newly hatched larvae were collected and reared in plastic vials (10 × 12 cm) along with selective food in the form of leaves.

Entomopathogenic nematodes

In this study, the 2 EPNs, S. feltiae (HR1) and H. bacteriophora (HR2) were used directly in the experiments after isolation. The native isolate was obtained from fruit orchards soil samples, collected from of 1682 m above mean sea level with 30o 53′ 15 N latitude and 77° 16′ 07 E longitude with the mid-hill zone of western Himalayas Rajgarh, Sirmaur district, Himachal Pradesh, India, using Galleria mellonella (L.) larvae as nematode baiting traps. The isolates were cultured based on the method (Kaya and Gaugler 1993) at 21 ± 1 °C on the last instar larvae of G. mellonella. Infective juveniles (IJs) that emerged during the first 10 days were collected from white traps stored at 4 °C in distilled water for up to 14 days. The nematodes were acclimatized at room temperature for about 30 min before being used in the experiments.

Effect of nematode concentrations

Bioassays were conducted in Petri dishes (9 cm). Each unit was filled by 20 g of sand soil (Table 1). Soil moisture was adjusted to 7% (w/w). IJs were uniformly applied to the soil surface at 0, 5, 10, 20, 40, 80, and 160 IJs/cm2 in 1 ml of distilled water. The final soil moisture was 10% (w/w). The containers were then kept at room temperature for 1 h before every instar’s 10 P. brassicae larvae per container were placed on the soil surface. There were 4 replicates for each concentration. The containers were kept for 72 h under controlled conditions in a growth chamber. Then, the larvae were separated from the substrate by gentle sieving and were individually maintained in controlled conditions until adult emergence. Three days later, 25% of the dead larvae were selected randomly and dissected under a stereomicroscope image analyzing software (Olympus Soft Imaging Solutions) to confirm nematode infection. The experiment was conducted twice.

Larvicidal activity

Each nematode species was added at different concentrations (1.00, 1.30, 1.60, 1.90, 2.20 IJs/cm2) into the 9 cm Petri dish in triplicate with 2 ml of dechlorinated sterile water and 10 larvae of tested P. brassicae strains. The 2nd and 4th larval instars were provided by young age (vegetative stage) cabbage leaves. One Petri plate without EPNs suspension was used as a control. After 24, 48, and 72 h the number of dead larvae was calculated. The strains that killed more than 50% of the larvae were considered pathogenic. Both nematode isolates were examined quantitatively for larvicidal activity against P. brassicae, using various concentrations of EPNs’ suspensions. The infected larvae were observed under a stereo zoom microscope for each concentration at 72 h exposure time.

Statistical analysis

Insect mortality was control-corrected (Abbott 1925) and Arcsine transformed when required to meet assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances. In all experiments, control-corrected mortality was subjected to one-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA)

The corrected percent mortality data thus obtained for different concentrations of P. brassicae (L.) at different concentrations were subjected to probit analysis as per the method given by Finney 1971. Concentration-mortality response data was conducted. Also, LSD (P < 0.05) values were calculated to differentiate means among treatments.

Results

Bioassay of P. brassicae

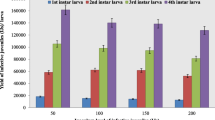

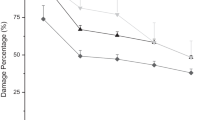

Data of the efficacy of EPNs for the control of larvae P. brassicae are presented in Table 1. Percent of P. brassicae larval mortality treated with the tested EPN isolates was significantly higher than the untreated control. Results revealed that the percent of larval mortality significantly increased with the increase in time periods where it being maximum at 72 h. and followed at 48 and then 24 h. The highest per cent of larval mortality was recorded on the 2nd instar larvae for treatments with H. bacteriophora (72.08%) and S. feltiae (67.42%) at 160 IJs/cm2, followed by those at 80 IJs/cm2 (56.92%) same results for both EPNs, while the larval mortality % by H. bacteriophora at 40 IJs/cm2 was (49.37%) and by S. feltiae at 160 IJs/cm2 was (52.31%) (Fig. 1). The followed results were recorded on the 4th instar larval mortality at treatment with H. bacteriophora (85.38%) and then by S. feltiae (69.50%) at 160 IJs/cm2 (Fig. 2). Pupal mortality was (74.12%) by H. bacteriophora and (74.12%) by S. feltiae at 160 IJs/cm2. But at 80 IJs/cm2, the larval mortality rates were (62.12%) and (58.58%) by H. bacteriophora and S. feltiae, respectively (Fig. 3). There was no larval mortality observed in the untreated control.

After 48 h, the treatment showed the highest percent of larval mortality (58.58%) at the 2nd instar for H. bacteriophora and (55.26%) for S. feltiae at 160 IJs/cm2, followed by H. bacteriophora and S. feltiae at 80 IJs/cm2 (50.81 and 47.86%, respectively). H. bacteriophora and S. feltiae caused mortality rate of (43.54%) for both at 40 IJs/cm−2 (Fig. 1). The treatments of the 4th instar larval mortality were (74.12%) for H. bacteriophora, followed by (63.78%) for S. feltiae at 160 IJs/cm2 (Fig. 2). Pupal mortality was (63.78%) for H. bacteriophora and (55.26%) for S. feltiae at 80 IJs/cm2. The efficacy of EPNs on pupal mortality recorded for H. bacteriophora (61.74%), and (60.08%) for S. feltiae at 160 IJs/cm2. H. bacteriophora and S. feltiae caused (53.75%) and (52.31%) for larval mortality, respectively, at 80 IJs/cm2. There was no larval mortality observed in the untreated control (Fig. 3).

After 24 h., the results showed that the highest mortality percent of the 2nd instar larvae was (46.42%) and (44.98%) that recorded in treatments with S. feltiae and, H. bacteriophora, respectively, at 160 IJs/cm2, followed by those at 80 IJs/cm2 (40.65 and 37.71%, respectively), and then at 40 IJs/cm−2 (36.20 and 34.70%, respectively). The next best result was (61.74%) for the mortality of 4th instar larvae by H. bacteriophora at 160 IJs/cm2, followed by (53.75%) for S. feltiae at the same concentration. Pupal mortality was (50.81%) and (47.86%) by H. bacteriophora and S. feltiae, respectively, at 160 IJs/cm2, but (46.12%) and (43.54%) for EPNs at 80 IJs/cm2. There was no larval mortality observed in the untreated control. Non-highly significant differences existed among the remaining treatments.

Bioassay of Log probit analysis larvicidal activity

The virulence was conducted to estimate the lethal concentrations of EPNs to different larval instars of P. brassicae. The data reflecting the efficacy of the two isolates of S. feltiae (HR1) and H. bacteriophora (HR2) against 2nd, 4th larval instars and pupae of P. brassicae are summarized in (Table 2). EPN was applied at 10, 20, 40, 80 and 160 IJs/cm2, caused P. brassicae are recorded when the EPNs (at LC50 level) were applied at 48 and 72 h after EPN treatment either LC90 level (Table 2). An effect was observed when EPNs was applied at LC90 in the best larvicidal activity was obtained during the 72 h of exposure. S. feltiae (HR1) and followed by H. bacteriophora (HR2) EPN strains showed potent larvicidal activity at low concentration even at 48 and 72 h of exposure (Table 2).

Discussion

Overall results on efficacy of the tested EPNs indicated that treatment of 4th instar larvae by H. bacteriophora at 160 IJs/cm2 (85.38%) was found to be a superior than other treatments. However, treatment with S. feltiae at 160 IJs/cm−2 was found to be the next effective treatment. Hence, the results of the present study corroborate the finding of Sharma et al. (2018) who reported that P. brassicae caused larval net mortality of 86.2 and 66.5% under laboratory conditions, respectively. Similar results were also reported by (Askary and Ahmad, 2020). Mantoo and Zaki (2014) obtained results confirm the findings of an increase in inoculum level of IJs, time consumed for larval mortality decreased but when the larval size increased the time consumed in larval mortality also increased, it was also shown that the EPNs could be an effective alternative to insecticides. Controlling insect pests with a foliar application is becoming a more widely-used practice Laznik et al. (2010).

The mortality was determined through different concentrations after 48 and 72 h exposure. The mortality rate depends on the concentration and exposure time. However, the highest mortality range was observed at H. bacteriophora treatment at very low concentrations after 48 and 72 h. Even though S. feltiae showed a slow mortality in 48 and 72 h of exposure time, they restrained the larval development at the early pupal stage. The results are similar to the findings of EPNs’ pathogenicity of H. bacteriophora against vine mealy bug, in South African vineyards Sabry et al. (2016). The data revealed that the mortality rate increased with the increase in time intervals viz., 24, 48, and 72 h.

Obtained results confirm the findings of Mantoo and Zaki (2014) who observed that with the increase in inoculum level of IJs, time consumed for larval mortality decreased but when the larval size increased the time consumed in larval mortality also increased. Similar findings were also reported by other research workers Askary and Ahmad (2020) and Abbas et al. (2021).

Conclusions

The efficacy of local indigenous EPN isolates was significantly superior to that of the exotic species. High EPN efficacy obtained under laboratory conditions cannot easily be extrapolated to field efficacy; therefore, future field experiments are justified to fully determine the potential of local EPN isolates against P. brassicae in Himachal Pradesh and Indian, conditions.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article.

Abbreviations

- EPNs:

-

Entomopathogenic nematodes

- IJs:

-

Infective juveniles

- B.O.D:

-

Biological oxygen demand

- OPSTAT:

-

Operational Status

- cm2 :

-

Centimeter square

- h:

-

Hour

- LSD:

-

Least significant difference

References

Abbas W, Javed N, Haq IU, Ahmed S (2021) Pathogenicity of entomopathogenic nematodes against cabbage butterfly (Pieris brassicae) Linnaeus (Lepidoptera: Pieridae) in laboratory conditions. Int J Trop Insect Sci 41:525–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42690-020-00236-2

Abbott WS (1925) A method of computing the effectiveness of an insecticide. J Econ Entomol 18:265–267

Arthurs S, Heinz KM, Prasifka JR (2004) An analysis of using entomopathogenic nematodes against above-ground pests. Bull Entomol Res 94:297–306. https://doi.org/10.1079/BER2003309

Askary TH, Ahmad MJ (2020) Efficacy of entomopathogenic nematodes against the cabbage butterfly (Pieris brassicae (L.) (Lepidoptera: Pieridae) infesting cabbage under field conditions. Egypt J Biol Pest Control 30:39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41938-020-00243-y

Forst S, Clarke D (2002) Bacteria–nematode symbiosis. In: Gaugler R (ed) Entomopathogenic nematology. CABI Publishing, pp 57–77. ISBN 0851995675

Grewal PS, Ehlers RU, Shapiro-Ilan DI (2005) Nematodes as biocontrol agents. CABI Publishing. ISBN 0851990177

Head J, Lawrence AJ, Walters KFA (2004) Efficacy of the entomopathogenic nematode, Steinernema feltiae, against Bemisia tabaci in relation to plant species. J Appl Entomol 128:543–547. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0418.2004.00882.x

Kaya HK, Gaugler R (1993) Entomopathogenic nematodes. Annu Rev Entomol 38:181–206. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.en.38.010193.001145

Laznik Z, Toth T, Lakatos T, Vidrih M, Trdan S (2010) Control of the Colorado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata [Say]) on potato under field conditions: a comparison of the efficacy of foliar application of two strains of Steinernema feltiae (Filipjev) and spraying with thiametoxam. J Plant Dis Prot 117:129–135

Laznik Z, Trdan S (2014) The influence of insecticides on the viability of entomopathogenic nematodes (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae and Heterorhabditidae) under laboratory conditions. Pest Manag Sci 70:784–789

Lewis EE, Campbell JC, Griffn C, Kaya HK, Peters A (2006) Behavioural ecology of entomopathogenic nematodes. Biol Control 38:66–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2005.11.007

Mantoo MA, Zaki FA (2014) Biological control of cabbage butterfly, Pieris brassicae by a locally isolated entomopathogenic nematode, Heterorhabditis bacteriophora SKUAST-EPN-Hr-1 in Kashmir. SKUAST J Res 16:66–70

Mazurkiewicz A, Tumialis D, Pezowicz E, Skrzecz I, Błażejczyk G (2017) Sensitivity of Pieris brassicae, P. napi and P. rapae (Lepidoptera: Pieridae) larvae to native strains of Steinernema feltiae (Filipjev, 1934). J Plant Dis Prot 124:521–524. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41348-017-0118-4

Poinar GO (1990) Biology and taxonomy of Steinernematidae and Heterorhabditidae. In: Gaugler R, Kaya HK (eds) Entomopathogenic nematodes in biological control. CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp 23–58

Sabry AH, Metwallya HM, Abolmaatyb SM (2016) Compatibility and efficacy of entomopathogenic nematode, Steinernema carpocapsae all alone and in combination with some insecticides against Tuta absoluta. Der Pharm Let 8:311–315

Sharma R, Singha B, Choudhury SR, Sharma G (2018) Isolation and microscopic investigation of Entomopathogenic nematodes (EPNs) occurring in Barak Valley, Assam, India. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci 7:1835–1839

Sicard M, Brugirard-Ricaud K, Pages S, Lanois A, Boemare NE, Brehelin M, Givaudan A (2004) Stages of infection during the tripartite interaction between Xenorhabdus nematophila, its nematode vector, and insect hosts. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:6473–6480. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.70.11.6473-6480.2004

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Dr. Yashwant Singh Parmar University of Horticulture and Forestry, Nauni, Solan, HP, India-173230 for support of this research. We are also grateful to Department of entomology, Nematology laboratory used in this study. Indian council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) for providing necessary facilities and financial support, respectively.

Funding

No funding from any source.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors jointly designed the experiment. KI conducted the laboratory bioassays, performed data analysis and drafted the manuscript with inputs from all authors. MS, MW, MK, MW, DA and HG collaborated closely with KI in the whole process especially during data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Indra Kumar Kasi is Ph.D. Research Scholar and has specialization in Agriculture Entomology. Mohinder Singh (Ph.D., PDF) is Principal Scientist and incharge of Nematology laboratory, Department of Entomology, Dr YSP UHF, India.

Kanchhi Maya Waiba is Junior Research fellow has specialization in Vegetable Science, CSK HPKV Palampur, India. Other authors are collaborating with laboratory work Nematology laboratory, Dr YSP UHF, India.

S. Monika is Ph.D. Research Scholar and has specialization in Agriculture Entomology, Dr YSP UHF, India.

M. A. Waseem is Ph.D. Research Scholar and has specialization in Agriculture Entomology, Dr YSP UHF, India.

D. Archie is Junior Research Fellow and has specialization in Agriculture Entomology, Dr YSP UHF, India.

Himanshu Gilhotra is Junior Research Fellow and has specialization in Agriculture Entomology, Dr YSP UHF, India.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

We, the authors do not have competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kasi, I.K., Singh, M., Waiba, K.M. et al. Bio-efficacy of entomopathogenic nematodes, Steinernema feltiae and Heterorhabditis bacteriophora against the Cabbage butterfly (Pieris brassicae [L.]) under laboratory conditions. Egypt J Biol Pest Control 31, 125 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41938-021-00469-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41938-021-00469-4