Abstract

The virulence and proteolytic activity of some entomopathogenic fungi isolates, viz., Metarhizium anisopliae, Beauveria bassiana, Verticillium lecanii, and Trichoderma harzianum, against the two-spotted spider mite, Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae), were evaluated. Common maize plants (Zea mays L.) infested with females of T. urticae were treated in vivo by spraying with suspensions of 1 × 108 conidia ml−1 concentration of selected isolates. Lethal effects of fungal isolates were assessed as percentages of daily mortalities of mites, compared to the mortality in control. Virulence of the fungi isolates was estimated based on the LC50 values calculated by probit analysis for the individuals treated by 1 × 105 conidia ml−1 concentration. Proteolytic activity of isolates was assayed on casein substrate to reflect their virulence towards T. urticae. The mite mortality rates increased with increasing conidial concentrations as well as days after treatment. The mortality rate caused by M. anisopliae isolate varied from 18.75 to 85%, with LC50 value of 4.6 × 105 conidia/ml and LC90 value of 2.4 × 108 conidia/ml during 7 days, respectively. The isolate of B. bassiana caused 15 to 70% mortality, and its LC50 and LC90 values estimated 3.3 × 106 and 7.8 × 109 conidia/ml, respectively. However, V. lecanii isolate caused 11.25 to 72.50% mortality with LC50 of 5.2 × 106 conidia/ml, while T. harzianum was potentially less virulent than other isolates causing 8.75 to 63.75% mortality rate to T. urticae with LC50 of 9.4 × 106 conidia/ml. M. anisopliae showed the highest proteolytic activity at all concentrations, followed by B. bassiana in 3rd, 5th, and 7th day post treatment. These findings recommend the selection of virulent fungal isolates for use as natural and environmentally safe agents in biological control programs to combat mite pests.

Similar content being viewed by others

-

1.

The two-spotted spider mites T. urticae were sensitive and affected by entomopathogenic fungi.

-

2.

M. anisopliae isolate had the most lethal effect, but the isolates V. lecanii, B. bassiana and T. harzianum were less lethal.

-

3.

M. anisopliae was the highest virulent isolate against T. urticae than the other isolates with LC50 4.6 × 105 ppm.

-

4.

Protease activities of fungal isolates were increased with increased conidia concentrations from 1 × 105 and up to 1 × 108 conidia ml−1.

-

5.

M. anisopliae gave the highest activities at all concentrations, compared with other isolates, followed by B. bassiana which exceeded V. lecanii and T. harzianum in its proteolytic activities.

Background

Spider mites (Acari: Prostigmata: Tetranychidae) are obligated predatory plant mites, which are unique in possessing highly elongated movable stylets used to puncture the individual cells of their host plants (Walter et al., 2009). Pests of known economic significance belonging to this group are the two-spotted mites, Tetranychus urticae Koch, which are considered as violent pest that affects vegetables, orchards, medicinal, and ornamental plants (Naher et al., 2006). The conventional control of this pest includes acaricides that have been widely used for mite control in greenhouses, orchards, and many other cropping systems (Van Leeuwen et al., 2005), but it can cause undesirable problems like the death of natural enemies such as predators or development of pesticide-resistant races of mites and residue concerns (Draganova and Simova, 2010). Thus, the search for an eligible biocontrol agent is therefore a step in developing new environmentally friendly strategies or improving existing strategies that provide alternatives to conventional pest control. Research and biological control strategies for spider mites have largely focused on preserving natural enemies and releasing predator mites (Zhang, 2003), and nevertheless, an additional spray of acaricides is needed.

The entomopathogenic fungi (EPF), developed as mycoacaricides, can naturally manage mite populations and can be used in a useful control strategy as stand-alone to replace synthetic acaricides already used, or as an integrated component for mite management (Maniania et al., 2008). The fungus penetrates the pest cuticle with the help of hyphae protrusion germinated from the conidia, as soon as contact to the host (Revathi et al., 2011). The EPF rely on their enzymatic capacity to degrade the integument of insects or mites, consisting of lipases, proteases, and chitinases, furthermore, glutaminase, β-galactosidase, and catalase as well (Mondal et al., 2016). Fungal proteases seem to be particularly important in the penetrating process since the insect and mite cuticle comprises up to 70% protein (Charnley, 2003). The virulence of the EPF against their hosts can be verified through their production of cuticle-degrading enzymes (Pinto et al., 2002). The successful use of EPF as agents for biological control of mites ultimately depends upon the extent of selected fungal strains (Maniania et al., 2008).

The goal of this study was to determine the activity of protease and the virulence of 4 EPF isolates against the two-spotted spider mite, T. urticae.

Material and methods

Isolation of fungi, culture conditions, purification, and identification

The fungi, Metarhizium anisopliae, Beauveria bassiana, Verticillium lecanii, and Trichoderma harzianum were collected from dead cadavers of the two-spotted spider mite individuals on leaf surface of maize plants (Zea mays L.). Samples containing fungi, wrapped in bags, were transferred to the Biological and Integrated Pest Control Laboratory, Plant Protection Institute, Zagazig, Egypt. Serial dilution method was used to isolate EPF according to the method of Goettel (1996). One ml of each soil dilution was poured onto Petri dishes containing Sabouraud’s dextrose agar (SDAY) medium (Merck, Germany) containing 1% yeast extract. To isolate the fungi grown on the surface of the mite body, the mites were superficially sterilized with 70% ethanol for 1 min and 5% sodium hypochlorite for 3 min and rinsed three times with sterile distilled water; then, the fungi were transferred to SDAY medium. The dishes were incubated at 25 °C for 15 days until the colonies appeared. Then, the colonies were selected, picked up, and maintained on PDA (potato dextrose agar) medium until identification. Fungal species were identified using the lacto-phenol cotton blue staining method according to Humber (2005). Single spore fungus was carried out according to Ho and Ko (1997). For preparation of the bioassay suspensions, the conidia of 10-day-old cultures, which were previously developed on SDAY medium, were harvested by washing with sterile distilled water containing 0.02% Tween 80, followed by decimal dilutions of the conidial suspensions obtained and their concentrations estimated using a hemocytometer under light microscope (Zeiss) (× 40 magnification).

Mite culture

Females of T. urticae were obtained from the Biological and Integrated Pest Control Laboratory, Plant Protection Institute, Zagazig, Egypt, and transferred to caged maize plants for subsequent culturing. A stock colony was established in ventilated jars (26 × 20 × 10 cm) at 32 ± 2 °C, 55% R.H., and 16:8 (L:D) photoperiod. To avoid the excessive accumulation of excrements and exuviae of larvae, the growing media were updated three times weekly.

Protease assay

Casein substrate was used to determine protease enzyme activity (Vyas and Deshpande, 1989). A mixture of 2 ml reaction contained an aliquot of an appropriately diluted enzyme solution, 10 mg substrate (casein) in 0.2 mM sodium carbonate buffer, pH 9.7. The enzyme reaction mixture was incubated at 35 °C for 20 min and then 3 ml trichloroacetic acid (TCA) was added (2.6 ml 5% TCA + 0.4 ml 3.3 N HCl). The mixture was centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 5 min, and the resultant was observed at 280 nm (Ultrospec II, LKB Biochrom, UK). One international unit (IU) is defined as an enzyme activity that produced 1 μmole of tyrosine per min.

Virulence test

Bioassays were conducted under laboratory conditions (23 ± 1 °C, photoperiod 12:12 L:D). Females of mites were taken from the cultured source and gently transferred onto caged maize plants with the help of a fine camel hair brush. T. urticae was used as a host for the EPF reared on maize plants in earthen pots. Population of mites was counted on individual plants (having 4–5 leaves) before performing sequential sprays of fungi. The plants were divided into 4 groups (4 isolates), each of which containing 5 plants (4 treatments + control). Five plants in each treated group were sprayed with a selective fungus with recommended concentration (1 × 105, 1 × 106, 1 × 107, and 1 × 108 conidia ml−1). These concentrations were applied by foliar application with hand atomizers on potted plants. In all cases, 300 μl of each conidial concentration, with Tween 80 solution of 0.02%, were directly sprayed on 10 adult female mites. Control plants received same volume of water containing 0.02% Tween 80. The whole experiment was repeated 3 times. Mite mortality was estimated 3, 5, and 7 days after treatment. Plant leaves carrying dead mites were incubated in a humid chamber to allow the germination of fungus conidia and confirm that the death was due to mycoses. Smears were prepared from dead mites stained with methylene blue, then observed under a light microscope. Fungal lethal effects were assessed as percentages of daily cumulative mortality due to mycoses, compared to mortality in untreated control. Virulence of fungal isolates was calculated by probit analysis (Finney, 1971) depending on the median lethal concentration (LC50) of the individuals treated with 105 conidia ml−1 suspensions. Confidence intervals of varying LC50 values were calculated at P level < 0.05.

Statistical analysis

Data were corrected for control mortality using Abbott’s formula (Abbott, 1925). The mortality of each treatment was analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and means compared by Tukey’s HSD test (SPSS 16.0). The LC50 and LC90 and their 95% fiducial limits were calculated from probit analysis (Finney, 1971) using the Minitab 15 computer software.

Results and discussion

Virulence of entomopathogenic fungi against T. urticae

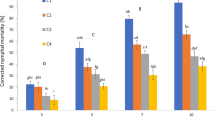

The bioassay revealed that M. anisopliae, B. bassiana, V. lecanii, and T. harzianum can be biologically employed to control T. urticae. Fungal lethal effects were assessed as percentage of daily cumulative mortality due to mycoses, compared to mortality in control. In general, the mortality of T. urticae was found to be the highest with increasing conidial suspensions from 1 × 105 and up to 1 × 108 conidia ml−1 (Figs. 1, 2, 3, and 4). Also, data showed that the mortality rate of T. urticae females increased significantly after 7 days more than those after 3 days and/or 5 days of spraying at all concentrations. This trend of deaths over the days after inoculation pointed that the advanced infections and deaths appeared from the third day and continued until the seventh. These results suggested that the experiments with some EPF require a long incubation time before evaluating their results (Amjad et al., 2012). Tamai et al. (2002) reported that all isolates of M. anisopliae and B. bassiana were pathogenic to T. urticae with increased mortality rates after the 3rd day and peaking on the 4th or 5th day post treatment. Thus, the bioassay of some EPF against mites requires a long period of incubation before evaluating the results. This delay may be regarded to the time needed for infectivity process of adhesion, penetration, germination, and fungus growth (Ekesi, 2001).

Lethal effect of Trichoderma harzianum isolate against Tetranychus urticae after treatment with conidial suspensions at concentration 1 × 105, 1 × 106, 1 × 107, 1 × 108 conidia ml−1 (control variant, 0 conidia) Error bars: SD

M. anisopliae isolate had the most lethal effect even at low concentration (1 × 105) reaching 18.75, 23.75, and 36.25% on the 3rd, 5th, and 7th day of spraying, respectively, than other isolates (Fig. 1). After treatment with the highest concentrations (1 × 107 and 1 × 108 conidia ml−1), M. anisopliae developed mycosis for T. urticae individuals with fast lethal effect caused 40.00 % after 3 days, 51.25% after 5 days, and 85.00% after 7 post-inoculation days.

The isolates V. lecanii and B. bassiana were found highly virulent to T. urticae individuals with mortality rates 72.50 and 70.00, at 1 × 108 conidial ml−1 concentration, respectively. This finding was consistent with Wekesa et al. (2005) who tested 2 isolates of B. bassiana and 17 isolates of M. anisopliae against T. evansi and observed 80% mortality rate in mite population at a high concentration (1 × 108 conidia ml−1) caused by the 2 isolates. Also, Shi and Feng (2009) used B. bassiana, Paecilomyces fumosoroseus, and M. anisopliae isolates 10 days after spraying where they caused 73.1, 75.4, and 67.9% mortality rates of mites, respectively. On the reverse, M. anisopliae isolate remained least effective against females of T. urticae (Amjad et al., 2012), while V. lecanii and P. fumosoroseus showed more than 75% mortality (76.25 and 79.16%, respectively) at the highest lethal concentration 1 × 108 conidia/ml, 8 days after fungal application. On the other hand, T. harzianum was less lethal where it showed potency reaching 63.75% of deaths, 7 days after inoculation. Regarding the virulence of the 4 isolates, there were non-significant differences at P level < 0.05.

It was also shown that B. bassiana exceeded both V. lecanii and T. harzianum in mortality percentages at low concentrations (1 × 105 and 1 × 106 conidia ml−1) (Figs. 2, 3, and 4), while V. lecanii exceeded at the highest concentration (1 × 108 conidia ml−1) during inoculation days (Fig. 3). The mortality rates in the variants treated with 1 × 105 and 1 × 106 conidial suspensions of B. bassiana strain were as follows: 15.00, 18.75, and 28.75; 23.75, 27.50, and 43.75% at the 3rd, 5th, and 7th day post treatment, respectively. Meanwhile, a high lethal effect recorded 43.75, 51.25, and 72.50% was obtained with V. lecanii at the 1 × 108 conidia ml−1 concentration on the 3rd, 5th, and 7th day after treatment, respectively.

Virulence data demonstrated the efficacy of M. anisopliae strain in controlling mite individuals where they had the lowest LC50 value of 4.6 × 105 conidia/ml, followed by B. bassiana which was less virulent to T. urticae having LC50 of 3.3 × 106 conidia/ml (Table 1). The efficacy trials carried out in the field are largely supported by laboratory tests. While searching for microbial control agents in laboratory experiments, several workers have found that the mobile stages of T. urticae were sensitive and influenced to a large extent by the tested isolates of B. bassiana and M. anisopliae (Tamai et al., 2002; Chandler et al., 2005; Draganova and Simova, 2010; Schapovaloff et al., 2014 and Zare et al., 2014). It was also found that T. harzianum was the least virulent fungus with LC50 9.4 × 106 conidia/ml. Considering the toxicity index percentage at LC50, M. anisopliae was the most toxic fungus with a strong toxicity index 100%, followed by B. bassiana, V. lecanii, and T. harzianum with 13.94, 8.85, and 4.89%, respectively. Given the toxicity levels of LC90, M. anisopliae was also the strongest virulent with toxicity index of 100%, followed by V. lecanii, B. bassiana, and T. harzianum with toxicity index 11.43, 3.07, and 0.68%, respectively.

V. lecanii had the highest slope value of (0.489), followed by M. anisopliae (0.469), while T. harzianum was the lowest one (0.358) and B. bassiana had slope of the nearest value of 0.380 (Table 1). The slopes of all listed fungi are considered of low values indicating a certain amount of heterogeneity in the population towards the tested fungi.

Pathogenicity test

All isolates of M. anisopliae, B. bassiana, V. lecanii, and T. harzianum infected mite individuals causing mortality (Fig. 5a–d). They demonstrated rapid external hyphal development and sporulation under moist condition. Firstly, filamentous hyphae were evolved from the anal region of the mite cadaver and then quickly covered the cadaver, followed by sporulation within 7 days. Investigation of smears of cadaver of mites confirmed mycosis infectivity as cause of death in individuals treated with conidial suspensions of the fungal isolates. Considering the deadly effect of the tested fungi to T. urticae was due to the secondary metabolites toxicity and the dyes they produced (Tamai et al., 2002), a variety of degrading enzymes were produced by EPF worked in a coordinated manner, popularly known as cuticle degrading enzymes, including chitinases, proteases, and lipases, making their entry through the massive barriers of mite cuticle easier (Krieger de Moraes et al., 2003; Zare et al., 2014).

a. Individuals of T. urticae infected with M. anisopliae after 7 days treatment. b. T. urticae individuals infected with B. bassiana after 4 days treatment. c. T. urticae individuals infected with V. lecanii after 7 days treatment. d. T. urticae individuals infected with T. harzianum after 7 days treatment (all images were taken with a Leica EZ 4D dissecting microscope at ~ × 16)

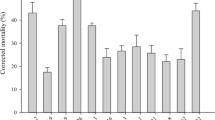

Protease activity

Proteases are considered to be the most important in the infectious process (Mustafa and Kaur, 2009). The dissolved proteins were further degraded into amino acids by exopeptidases and amino peptidases in order to provide nutrients for entomopathogenic fungi (Wang et al., 2002). The present results showed that protease activities of fungal isolates were increased by conidia concentrations from 1 × 105 and up to 1 × 108 conidia ml−1. M. anisopliae gave the highest activities at all concentrations than other isolates, yielding 1.032, 1.361, 1.977, and 2.111 U/ml at 1 × 105, 1 × 106, 1 × 107, and 1 × 108 conidia ml−1 concentrations, respectively (Fig. 6). This is followed by B. bassiana, which exceeded V. lecanii and T. harzianum in its proteolytic activities at 1 × 105, 1 × 106, and 1 × 107 conidia ml−1 concentrations yielding 0.897, 0.964, and 1.121 U/ml, respectively. V. lecanii exceeded B. bassiana at the highest concentration (1 × 108) yielded 1.356 U/ml enzyme activity. T. harzianum was higher than V. lecanii at low concentrations (1 × 105 and 1 × 106 conidia ml−1) while lower at higher concentrations (1 × 107 and 1 × 108 conidia ml−1). In this respect, invasive fungi produce large quantities of serine-protease (Pr1), which degrades protein substances, after the epicuticle breakdown by lipases. The subtilisin-like serine-protease (Pr1) and trypsin-like protease (Pr2) are the most common studied protein decomposition enzymes. Pr1 and Pr2 activities have been detected in M. anisopliae, M. flavoviride, B. bassiana, Nomuraea rileyi, and Lecanicillium lecanni (Liu et al., 2007). Furthermore, the finding of protease Pr1 in EPF was considered as an indicator of virulence (Castellanos-Moguel et al., 2007).

Recent evidence indicated that different EPF isolates may show some degrees of variety in cuticle degrading proteases production (Pinto et al., 2002; Revathi et al., 2011 and Zare et al., 2014). These varieties may reflect differences observed in the virulence of isolates and species such that, isolates with high protease activity are expected to represent a high virulence towards their host. These findings were in accordance with obtained findings, which revealed a wide variation in the activities of proteases among the studied isolates. A positive correlation between proteases activity and virulence of isolates was found, so that the highest the protease activity of a particular isolate, the highest the virulence of that isolate against T. urticae. The present findings were also coincided with those obtained by Zare et al. (2014) who showed a wide diversity in proteolytic activity and virulence of studied isolates. Additionally, they found a positive correlation between the proteolytic activity on casein substrate and virulence of the isolates against the Khapra beetle Trogoderma granarium.

The present results revealed that the 2 virulent isolates M. anisopliae and B. bassiana showed the highest protease activities. It is well known that both the tested EPF produce higher enzymes of chitinases, proteases, and lipases than other fungi species (Revathi et al., 2011). Besides, M. anisopliae, B. bassiana, and V. lecanii secreted a diversity of extracellular hydrolytic enzymes in liquid cultures that contain locust cuticle as sole carbon source (St Leger et al., 1986).

Conclusion

Degrading enzymes might regulate many infectious processes and function as control agents. The finding has given biotechnology researchers an opportunity to implement bio-process engineering to produce these enzymes on a large scale, along with strategies to create applications for the enzymatic extracts, as well as potential applications such as mycoacaricides in a green technology-based environment.

Availability of data and materials

All data are available in the manuscript, and the materials used in this work are of high transparency and grade.

Abbreviations

- EPF:

-

Entomopathogenic fungi

- IU:

-

One international unit

- PDA:

-

Potato dextrose agar

- R.H.:

-

Relative humidity

- SDAY:

-

Sabouraud’s dextrose agar plus yeast extract

- TCA:

-

Trichloroacetic acid

References

Abbott WS (1925) A method of computing the effectiveness of an insecticide. J Econ Entomol 18(2):265–267

Amjad M, Bashir MH, Afzal M, Sabril MA, Javed N (2012) Synergistic effect of some entomopathogenic fungi and synthetic pesticides, against two spotted spider mite, Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae). Pakistan J Zool 44(4):977–984

Castellanos-Moguel J, González-Barajas M, Mier T, Reyes-Montes MR, Aranda E, Toriello C (2007) Virulence testing and extracellular subtilisin-like (Pr1) and trypsin-like (Pr2) activity during propagule production of Paecilomyces fumosoroseus isolates from whiteflies (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae). Rev Iberoam Micol 24(1):62–68

Chandler D, Davidson G, Jacobson RJ (2005) Laboratory and glasshouse evaluation of entomopathogenic fungi against the two-spotted spider mite, Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychidae), on tomato, Lycopersicon esculentum. Biocontrol Sci Technol 15(1):37–54

Charnley AK (2003) Fungal pathogens of insects: cuticle degrading enzymes and toxins. Adv Bot Res 40:241–321

Draganova SA, Simova SA (2010) Susceptibility of Tetranychus urticae Koch. (Acari: Tetranychidae) to isolates of entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana. Pestic Phytomed (Belgrade) 25(1):51–57

Ekesi S (2001) Pathogenicity and antifeedant activity of entomopathogenic hyphomycetes to the cowpea leaf beetle, Ootheca mutabilis Shalberg. Insect Sci Applic 21(1):55–60

Finney DJ (1971) Probit analysis, 3rd edn. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, p 383

Goettel MS (1996) Inglis GD In: Manual of techniques in insect pathology. Academic Press, USA

Ho WC, Ko WH (1997) A simple method for obtaining single-spore isolates of fungi. Bot Bull Acad Sin 38:41–44

Humber RA (2005) Entomopathogenic fungal identification, key to major genera. Available on: www.ars.usda.gov/SP2UserFiles/Place/1907051 0/APSwkshoprev.pdf

Krieger de Moraes C, Schrank A, Vainstein MH (2003) Regulation of extracellular chitinases and proteases in the entomopathogen and acaricide Metarhizium anisopliae. Curr Microbiol 46(3):205–210

Liu SQ, Meng ZH, Yang JK, Fu YK, Zhang KQ (2007) Characterizing structural features of cuticle-degrading proteases form fungi by molecular modeling. BMC Struct Biol 7:33

Maniania NK, Bugeme DM, Wekesa VW, Delalibera IJ, Knapp M (2008) Role of entomopathogenic fungi in the control of Tetranychus evansi and Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychidae) pests of horticultural crops. Exp Appl Acarol 46:256–274

Mondal S, Baksi S, Koris A, Vatai G (2016) Journey of enzymes in entomopathogenic fungi. Pacific Science Review A: Natural Science and Engineering 18:85–99

Mustafa U, Kaur G (2009) Extracellular enzyme production in Metarhizium anisopliae isolates. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 54(6):499–504

Naher N, Islam T, Haque MM, Parween S (2006) Effects of native plants and IGRs on the development of Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae). Univ J Zool Rajshahi Univ 25:19–22

Pinto FGS, Fungaro MHP, Ferreira JM, Valadares-Inglis MC, Furlaneto MC (2002) Genetic variation in the cuticle-degrading protease activity of the entomopathogen Metarhizium flavoviride. Genet Mol Biol 25(2):231–234

Revathi N, Ravikumar G, Kalaiselvi M, Gomathi D, Uma C (2011) Pathogenicity of three entomopathogenic fungi against Helicoverpa armigera. J Plant Pathol Microbiol 2(4):114

Schapovaloff ME, Alves LFA, Fanti ALP, Alzogaray RA (2014) Susceptibility of adults of the cerambycid beetle Hedypathes betulinus to the entomopathogenic fungi Beauveria bassiana, Metarhizium anisopliae, and Purpureocillium Lilacinum. J Insect Sci 14:127

Shi WB, Feng MG (2009) Effect of fungal infection on reproductive potential and survival time of Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychidae). Exp Appl Acarol 48(3):229–237

St Leger RJ, Cooper RM, Charnley AK (1986) Cuticle-degrading enzymes of entomopathogenic fungi: regulation of production of chitinolytic enzymes. J Gen Microbiol 132:1509–1517

Tamai MA, Alves SB, de Almeida JEM, Faion M (2002) Evaluation of entomopathogenic fungi for control of Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae). Arq Inst Biol, São Paulo 69(3):77–84

Van Leeuwen T, Van Pottelberge S, Tirry L (2005) Comparative acaricide susceptibility and detoxifying enzyme activities in field-collected resistant and susceptible strains of Tetranychus urticae. Pest Manag Sci 61(5):499–507

Vyas PR, Deshpande MV (1989) Chitinase production by Myrothecium verrucaria and its significance for fungal mycelia degradation. J Gen Appl Microbiol 35:343–350

Walter DE, Lindquist EE, Smith IM, Cook DR, Krantz GW (2009) Order Trombidiformes — In: Krantz GW, Walter DE (Eds). A manual of acarology, Third edition. Texas Tech University Press, Lubbock. p. 233-420

Wang C, Typas MA, Butt TM (2002) Detection and characterization of pr1 virulent gene deficiencies in the insect pathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae. FEMS Microbiol Lett 213(2):251–255

Wekesa VW, Maniania NK, Knapp M, Boga HI (2005) Pathogenicity of Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae to the tobacco spider mite Tetranychus evansi. Exp Appl Acarol 36(1-2):41–50

Zare M, Talaei-Hassanloui R, Fotouhifar K (2014) Relatedness of proteolytic potency and virulence in entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana isolates. J Crop Prot 3(4):425–434

Zhang ZQ (2003) Mites of greenhouses: identification, biology and control. CABI Publishing, Cambridge, p. 244

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to the personnel of Biological and Integrated Pest Control Laboratory, Plant Protection Institute, Zagazig.

Funding

This work was not supported by any funding body, but personally financed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The design and concept of the study was carried out by all authors; the last author EME performed the experimental part under the supervision of IME and OMOM. The analysis and interpretation of the data were done by IME and OMOM. Both EME and IME prepared the manuscript draft; then the manuscript was revised for important intellectual content by IME and OMOM. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals.

Consent for publication

The manuscript has not been published in completely or in part elsewhere. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Competing interests

The author declares that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elhakim, E., Mohamed, O. & Elazouni, I. Virulence and proteolytic activity of entomopathogenic fungi against the two-spotted spider mite, Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae). Egypt J Biol Pest Control 30, 30 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41938-020-00227-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41938-020-00227-y