Abstract

Three strains of entomopathogenic nematodes, labelled P5, P6 and PH, were isolated during surveys of agricultural soils of Pir Panjal Range, using insect baiting technique. Morpho-taxometrical studies and molecular data confirmed that these isolates belong to Heterorhabditis bacteriophora, making this finding the first report of this species from Jammu and Kashmir, India. Their distribution using a meta-analysis of GenBank records was attempted to assess. The morphology, morphometric studies and molecular data were conspecific to original description with minor deviations. Data analysis of the distribution showed that H. bacteriophora was the most ubiquitous throughout the South Africa subcontinent, but it was rarely found in Indian subcontinent having been isolated from 3 states throughout the country. As these 3 strains of H. bacteriophora are native to the hilly region of Kashmir Valley, they can be exploited for the control of target crop insect pests of the region. However, further studies are required regarding their life cycle, host range, virulence potential and survival capacity under extreme environmental conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Entomopathogenic nematodes (EPNs) of the genus Steinernema Travassos, 1927 and Heterorhabditis Poinar, 1976 are promising biological control agents against a variety of crop insect pests (Divya and Shankar, 2009; Kaya and Gaugler, 1993). They have short life cycle, a wide host range, capable of resisting under unfavourable conditions, easy to mass produce and apply under field conditions (Askary and Ahmad, 2017). In India, the research on EPNs was conducted primarily by exotic species/strains of some Steinernema species and Heterorhabditis bacteriophora, imported by researchers (Kaya et al., 2006), but these exotic EPNs often yielded inconsistent results particularly in field trials and this may be due to their poor adaptability to the local agro-climatic conditions. Besides, there was a concern that exotic EPNs might also have a negative impact on non-target organisms (Kaya et al., 2006). Therefore, keeping in view the biodiversity and environmental perspective, the research practitioners started paying attention to isolation of the native species of EPNs due to their adaptability and utility in biological control. Though, research on EPNs in India was initiated since the mid-1960s (Kaya et al., 2006), but exploration of indigenous EPNs strain started in 1990s (Sankaranarayanan and Askary, 2017) with the isolation and identification of H. indica (Poinar et al., 1992) from Coimbatore. In India, H. indica is the only new valid species of EPNs reported till date; however, previously described new species were either synonymized with already existing species or were included as species inquirendae (Bhat et al., 2019; Hunt and Subbortin, 2016).

The present study was undertaken for the first time in Kashmir Valley for the isolation, proper identification and taxonomic representation of EPN species with the decisive aim to exploit them in future as biopesticide against local crop insect pests.

Materials and methods

Isolation and examination of nematodes

Surveys were conducted in agricultural soils of Anantnag, the hilly areas of Pir Panjal Range, Jammu and Kashmir, India, for the presence of EPNs. The surveyed area is located at 33° 72′ North, 75° 14′ East and 1601 m above sea level, where the climate is semi-arid or tropical monsoon. A total of 110 soil samples were collected from the different vegetable growing fields and walnut orchards. The soil samples were brought to laboratory in well-labelled polythene bags and EPNs were isolated from them by Galleria soil baiting technique (Bedding and Akhurst, 1975) followed by the White trap method (White, 1927). Emerged infective juveniles (IJs) were stored and used for further studies as described by Bhat et al. (2018) and Suman et al. (2019).

Heterorhabditis bacteriophora was reared on last instar larvae of greater wax moth, Galleria mellonella L. and hermaphroditic and amphimictic generations were obtained by dissecting 4 and 6 days infected cadaver, respectively. The IJs were collected approximately 1 week after the emergence from cadaver. All the generations were heat killed by Ringer’s solution and fixed in triethanolamine formalin (Courtney et al., 1955). They were dehydrated by the Seinhorst method (Seinhorst, 1959) and further processed as described by Bhat et al. (2017 and 2019). The morphology and morphometric analysis of the specimens was conducted using a light compound microscope (Magnus MLX) and a phase contrast microscope (Nikon Eclipse 50i). Morphometric measurements were done by the help of inbuilt software of phase contrast microscope (Nikon DS-L1). The terminology used for the morphology of pharynx, stoma and spicules follows the proposals by De Ley et al. (1995) and Abolafia and Peña-Santiago (2017), respectively.

Molecular characterization

The total genomic DNA was isolated from the pool of IJ stages by using Qiagen Blood and Tissue Analysis Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). IJs were first washed separately with Ringer’s solution followed by washing in PBS solution. They were then transferred into a sterile Eppendorf tube (0.5 ml) and DNA was extracted following the manufacturer’s protocol. A fragment of rDNA containing the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions (ITS1, 5.8S, ITS2) was amplified using primers 18S: 59-TTGATTACGTCCCTGCCCTTT-39 (forward) and 28S: 59-TTTCACTCGCCGTTACTAAGG-39 (reverse) (Vrain et al., 1992). The PCR master mix consisted of ddH2O 16.8 μl, 10× PCR buffer 2.5 μl, dNTP mix (10 mM each) 0.5 μl, 1 μl of each forward and reverse primers, dream taq green DNA polymerase 0.2 μl and 3 μl of DNA extract. The PCR profiles used were as follows: 1 cycle of 94 °C for 3 min followed by 40 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 52 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 60 s and a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. PCR was followed by electrophoresis (45 min, 100 V) of 5 μl of PCR product in a 1% TAE (Tris–acetic acid–EDTA)-buffered agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide (Aasha et al., 2019). The amplified products were purified and sequenced in both directions at Bioserve Technologies Limited, Hyderabad India. Finally, amplified regions were annotated and submitted to the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under accession numbers MK256378, MK263023 and MK256358 for ITS rDNA regions of strains P5, P6 and PH, respectively.

Sequence alignment and phylogenetic analyses

The sequences were edited and compared with those deposited in GenBank by means of a Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) of the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (Altushul et al., 1990). All alignments with other relevant sequences were produced by default ClustalW parameters in MEGA 7.0 (Kumar et al., 2016) and optimized manually in BioEdit (Hall, 1999). The phylogenetic trees of the ITS rDNA were obtained by the minimum evolution method in MEGA 7.0 (Kumar et al., 2016). The evolutionary distances were computed using the p distance method (Nei and Kumar, 2000) and were expressed as the number of base differences per site. All characters were treated as equally weighted and gaps as missing data. Caenorhabditis elegans was used as out-group taxa and to root the trees.

Geographical distribution

Geographical distribution of H. bacteriophora was assessed, using a meta-analysis of GenBank records, as natural occurrence of species facilities is use in particular areas. The ITS sequence was selected for the analysis, as it enables a clear distinction of the species in steinernematid, unlike another frequently sequenced marker D2D3 region of the 28S rDNA (Bhat et al., 2019). For determining the sequences of H. bacteriophora, BLAST search was performed with the sequence of the type isolate (AY321477) as a search query. The sequences that showed 97% or higher similarity were downloaded and their identity was confirmed by phylogenetic analysis.

Results and discussion

The morphological and morphometric studies as well as the molecular sequencing data of ITS rDNA showed that the present strains, P5 (MK256378), P6 (MK263023) and PH (MK256358), were conspecific to H. bacteriophora (Poinar, 1976) and hence described as the same species. The genus Heterorhabditis contains 16 well-described species of which only 3 have been described from India: H. indica (Poinar, 1992), H. bacteriophora (Poinar, 1976) Sivakumar et al., 1989 and H. baujardi (Phan et al., 2003) Vanlalhlimpuia et al., (2018). This is the first valid report of the existence of H. bacteriophora in Pir Panjal Range of Kashmir Valley. Three slides of the first-generation female bearing one female on each slide, 2 slides of first-generation males bearing 3 males on each slide, 2 slides of each second-generation females and males bearing 2 and 3 specimens, respectively, on each slide is deposited in Museum of Department of Zoology, Chaudhary Charan Singh University, Meerut.

Diagnosis of Heterorhabditis bacteriophora

The morphology of the 3 strains of H. bacteriophora P5, P6 and PH was similar to original description; however, some minor differences were observed. The anal swelling of present specimens was very prominent in both hermaphroditic and amphimictic females, while in original descriptions, it is much prominent in hermaphroditic females than in amphimictic. The rest of the morphological features were very similar. However, H. bacteriophora PH was selected for morphometric measurements and comparative studies as they all displayed similar morphology. The morphometric measurements of adults and IJs of H. bacteriophora PH (Table 1) were found similar to the topotype population of H. bacteriophora (Poinar et al., 1976), but some deviations were seen with the original description. A comparison in morphometric parameters in all generations of strain PH with original description of H. bacteriophora has been depicted (Table 2).

Molecular characterization

The alignment file of ITS rDNA sequences of the present 3 strains P5 (MK 256378), P6 (MK263023) and PH (MK256358) showed 2 nucleotide differences with topotype population of H. bacteriophora (AY321477) at positions 324 (G in place of C) and 667 (C in place of T); however, PH in addition also showed 2 nucleotide difference at positions 16 (T in place of A) and 618 (G in place of T) with P5, P6 and topotype population. The ITS rDNA sequences of the three strains of Heterorhabditis showed zero total character difference with each other and with AY321477; however, they were separated from other described Heterorhabditis species by 19–199 bp (Table 3).

Phylogenetic analysis

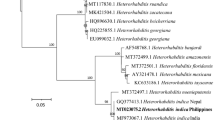

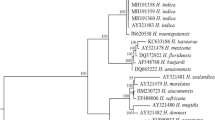

Phylogenetic analyses of the species of Heterorhabditidae based on ITS rDNA region showed a clear monophyly of the group formed by the 3 isolates (H. bacteriophora MK256378, H. bacteriophora MK263023 and H. bacteriophora MK256358) and original H. bacteriophora and several others, probably conspecific isolates (Fig. 1), thus confirming their identification. Sequences of H. bacteriophora formed a monophyletic group with ‘bacteriophora’ clade viz., H. georgiana Nguyen et al. (2008) and H. beicherriana Li et al. (2012), and together, they formed a sister clade with species of ‘megidis’ clade. The ITS rDNA region is conservative to resolve phylogenetic relations among closely related species.

Phylogenetic relationships of Heterorhabditis strains (P5, P6 and PH) with 16 Heterorhabditis spp. based on ITS rDNA sequences. Caenorhabditis elegans (X03680) was used as the out-group taxa. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (10,000 replicates) is shown next to the branches

Geographic distribution

The geographical dissemination of H. bacteriophora was evaluated by means of ITS rDNA records in NCBI database, although it has obviously many limits. The lack of the record from some areas does not mean that the organism is not present. On the other hand, the existing record means the presence of the species in that locality.

The original description of H. bacteriophora was from Brecon, South Australia by Poinar (1976) based on morphological characters only. Therefore, type sequence (AY321477) from the USA was used as a search query. H. bacteriophora strains were isolated in the USA (46); Pakistan (3); China (3); Switzerland (25); India (6); Argentina (6); Bulgaria (1), Lebanon (3); Egypt (1); South Africa (67); Iran (38); Portugal (11); Poland (3); Turkey (25); Nigeria (1); France (3); Hungary (1); Croatia (3); Jordan (5); New Zealand (1); Australia (1); Syria (5); UK (4); Slovenia (1); Iraq (1); Ireland (1) and Palestine (4). The majority of the sequences originate from the strains isolated in South Africa (67) followed by the USA (46). Based on the NCBI GenBank records, the species seems to be less reported in India, having been isolated from 3 states throughout the country. The records originate from North India (Jammu & Kashmir (3), Uttar Pradesh (2) and Haryana (1)). The number of the sequences in GenBank from a particular region reflects not only the abundance of the organism within the area but also the actual sampling effort. However, the species seems to be cosmopolitan, reported in almost all the continents except Antarctica but widely spread throughout the South Africa.

The abundance of H. bacteriophora was clear in comparison with other species of the ‘bacteriophora’ group of Heterorhabditis (Table 4). Based on the records in NCBI GenBank database, H. bacteriophora was the most frequently sequenced member of the ‘bacteriophora’ group (Table 4). The species with a worldwide distribution, H. bacteriophora has 269 records. Other closely related species have much lower number of records. The explanation for these differences is unclear, and further research in this field could bring interesting results. On the basis of above findings, it can be summarized that 3 strains of H. bacteriophora were indigenous to hilly areas of Jammu and Kashmir, which may be utilized as biological control tool against a variety of local crop insect pests. However, prior to this, further investigations are needed such as virulence and reproductive potential inside the host as well as survival of nematode under environmental extremes.

Availability of data and materials

The data and material of this manuscript are available on reasonable request.

References

Aasha, Chaubey AK, Bhat AH (2019) Notes on Steinernema abbasi (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae) strains and virulence tests against lepidopteran and coleopterans pests. J Entomol Zool Studies 7:954–964

Abolafia J, Peña-Santiago R (2017) On the identity of Chiloplacus magnus Rashid & Heyns, 1990 and C. insularis Orselli & Vinciguerra, 2002 (Rhabditida: Cephalobidae), two confusable species. Nematol 19:1017–1034. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685411-00003104

Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ (1990) Basic local alignment searchtool. J Mol Biol 215:403–410

Askary TH and Ahmad MJ (2017) Entomopathogenic nematodes: mass production, formulation and application. In: Abd-Elgawad MMM, Askary TH and Coupland J (eds.) Biocontrol agents: entomopathogenic and slug parasitic nematodes. CAB International, Wallingford, UK, pp 261–286.

Bedding RA, Akhurst RJ (1975) A simple technique for the detection of insect parasitic rhabditid nematodes in soil. Nematologica 21:109–110

Bhat AH, Chaubey AK, Půža V (2018) The first report of Xenorhabdus indica from Steinernema pakistanense: co-phylogenetic study suggests co-speciation between X. indica and its steinernematid nematodes. J Helminthol 92:1–10

Bhat AH, Chaubey AK, Shokoohi E, Mashela PW (2019) Study of Steinernema hermaphroditum (Nematoda, Rhabditida), from the West Uttar Pradesh, India. Acta Parasitol 64:1–18 https://doi.org/10.2478/s11686-019-00061-9

Bhat AH, Istkhar CAK, Půža V, San-Blas E (2017) First report and comparative study of Steinernema surkhetense (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae) and its symbiont bacteria from sub-continental India. J Nematol 49:92–102

Courtney WD, Polley D, Miller VL (1955) TAF, an improved fixative in nematode technique. Plant Dis Reptr 39:570–571

De Ley P, van de Velde MC, Mounport D, Baujard P, Coomans A (1995) Ultrastructure of the stoma in Cephalobidae, Panagrolaimidae and Rhabditidae, with a proposal for a revised stoma terminology in Rhabditida (Nematoda). Nematologica 41:153–182. https://doi.org/10.1163/003925995X00143

Divya K, Sankar M (2009) Entomopathogenic nematodes in pest management. Indian J Sci Technology 2:53–60

Hall TA (1999) BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98 NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser 41:95–98 https://doi.org/10.14601/Phytopathol_Mediterr-14998u1.29

Hunt DJ, Subbotin SA (2016) Taxonomy and systematics. In: Nguyen HB and Hunt DJ (eds). Advances in entomopathogenic nematode taxonomy and phylogeny Leiden, the Netherlands, Brill Publishing. pp. 13–58. Kaya HK and Gaugler R (1993) Entomopathogenic Nematodes. Annu Rev Entomol 38:181–206

Kaya HK, Aguillera MM, Alumai A, Choo HY, De la Torre M, Fodor A, Ganguly S, Hazir S, Lakatos T, Pye A (2006) Status of entomopathogenic nematodes and their symbiotic bacteria from selected countries or regions of the world. Biol control 38:134–155

Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K (2016) MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol 33:1870–1874 https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw054

Li XY, Liu QZ, Nermut’ J, Půža V, Mráček Z (2012) Heterorhabditis beicherriana n. sp. (Nematoda: Heterorhabditidae), a new entomopathogenic nematode from the Shunyi district of Beijing, China. Zootaxa 3569:25–40

Nei M and Kumar S (2000) Molecular evolution and phylogenetics. New York Oxford University Press 86:333. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2540.2001.0923.

Nguyen KB, Shapiro-Ilan DI, Mbata GN (2008) Heterorhabditis georgiana n. sp. (Rhabditida: Heterorhabditidae) from Georgia, USA. Nematol 10:433–448

Phan KL, Subbotin SA, Nguyen NC, Moens M (2003) Heterorhabditis baujardi sp. n. (Rhabditida: Heterorhabditidae) from Vietnam and morphometric data for H. indica populations. Nematol 5:367–382

Poinar GO Jr (1976) Description and biology of a new insect parasitic rhabitoid, Heterorhabditis bacteriophora n. gen. n. sp. (Rhabditida; Heterorhabditidae n. family). Nematologica 21:463–470

Poinar GO Jr, Karunakar GK, David H (1992) Heterorhabditis indicus n. sp. (Rhabditida, Nematoda) from India: separation of Heterorhabditis spp. by infective juveniles. Fundam Appl Nematol 15:467–472

Rzhetsky A, Nei M (1992) A simple method for estimating and testing minimum evolution trees. Mol Biol Evol 9:945–967

Sankaranarayanan C and Askary TH (2017) Status of entomopathogenic nematodes in integrated pest management strategies in India. In: Abd-Elgawad MMM, Askary TH and Coupland J (eds.) Biocontrol agents: entomopathogenic and slug parasitic nematodes. CAB International, Wallingford, UK, pp 362-382.

Seinhorst JW (1959) A rapid method for the transfer of nematodes from fixative to anhydrous glycerine. Nematologica 4:67–69

Sivakumar CY, Jayaraj S, Subramanian S (1989) Observations on an Indian population of the entomopathogenic nematode, Heterorhabditis bacteriophora Poinar, 1976. Biol control 2:112–113

Suman, Bhat AH, Aasha, Chaubey AK, Abolafia J (2019) Morphological and molecular characterisation of Distolabrellus veechi (Rhabditida: Mesorhabditidae) from India. Nematol https://doi.org/10.1163/15685411-00003315

Travassos L (1927) Sobre o genera Oxysomatium. Bol Biol 5:20–21

Vanlalhlimpuia, Lalramliana, Lalramnghaki HC and Vanramliana (2018) Morphological and molecular characterization of entomopathogenic nematode, Heterorhabditis baujardi (Rhabditida, Heterorhabditidae) from Mizoram, northeastern India. J Parasit Dis 42:341-349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12639-018-1004-0.

Vrain TC, Wakarchuk DA, Levesque AC, Hamilton R (1992) Intraspecific rDNA restriction fragment length polymorphisms in the Xiphinema americanum group. Fundam Appl Nematol 15:563–574

White GF (1927) A method for obtaining infective nematode larvae from cultures. Science 66:302–303

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Head of Department of Zoology, Chaudhary Charan Singh University, Meerut, for providing necessary lab facilities.

Funding

There are no funding sources for this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The design of the study was done by all authors, but second author (TAA) isolated the nematodes from soils samples. All molecular work and the analysis, interpretation of the data and writing were done by the first author (AHB). Both S and A calculated morphometric measurements and reference setting; then, the manuscript was finally revised by TAA and MJA. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals.

Consent for publication

The manuscript has not been published in completely or in part elsewhere.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bhat, A.H., Askary, T.H., Ahmad, M.J. et al. Description of Heterorhabditis bacteriophora (Nematoda: Heterorhabditidae) isolated from hilly areas of Kashmir Valley. Egypt J Biol Pest Control 29, 96 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41938-019-0197-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41938-019-0197-6