Abstract

Background

Previous research has shown an unclear and inconsistent association between fatigue and disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). The aim of this study was to explore differences in “between-person” and “within-person” associations between disease activity parameters and fatigue severity in patients with established RA.

Methods

Baseline and 3-monthly follow-up data up to one-year were used from 531 patients with established RA randomized to stopping (versus continuing) tumor necrosis factor inhibitor treatment enrolled in a large pragmatic trial. Between- and within-patient associations between different indicators of disease activity (C-reactive protein [CRP], erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR], swollen and tender joint count [ SJC and TJC], visual analog scale general health [VAS-GH]) and patient-reported fatigue severity (Bristol RA Fatigue Numerical Rating Scale) were disaggregated and estimated using person-mean centering in combination with repeated measures linear mixed modelling.

Results

Overall, different indices of disease activity were weakly to moderately associated with fatigue severity over time (β’s from 0.121 for SJC to 0.352 for VAS-GH, all p’s < 0.0001). Objective markers of inflammation (CRP, ESR and SJC) were associated weakly with fatigue within patients over time (β’s: 0.104–0.142, p’s < 0.0001), but not between patients. The subjective TJC and VAS-GH were significantly associated with fatigue both within and between patients, but with substantially stronger associations at the between-patient level (β’s: 0.217–0.515, p’s < 0.0001). Within-person associations varied widely for individual patients for all components of disease activity.

Conclusion

Associations between fatigue and disease activity vary largely for different patients and the pattern of between-person versus within-person associations appears different for objective versus subjective components of disease activity. The current findings explain the inconsistent results of previous research, illustrates the relevance of statistically distinguishing between different types of association in research on the relation between disease activity and fatigue and additionally suggest a need for a more personalized approach to fatigue in RA patients.

Trial registration Netherlands trial register, Number NTR3112.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Fatigue, although prioritized by patients, is a poorly understood symptom of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Fatigue is reported by almost 90% of patients with RA and around 40% of patients report clinically important levels of fatigue or severe fatigue [1, 2]. Qualitative research among RA patients with severe fatigue suggests that their fatigue is different from normal tiredness and is perceived by them as having far reaching consequences for all domains of daily life, by being intrusive and overwhelming [3]. Many patients prioritize fatigue as an important health outcome [4, 5] and therefore fatigue is now a core outcome measure in RA studies [6, 7]. Rheumatologists acknowledge the prevalence and impact of fatigue in their RA patients as 93% of the respondents of a questionnaire sent to rheumatologisst and trainees indicate that fatigue should still be considered a problem for patients even if pain is successfully resolved [8]. Despite this, fatigue is rarely a treatment target. This is mainly due to the lack of knowledge about the (patho)physiology of fatigue and the role of RA, in particular disease activity [9]. Although RA patients generally mention their disease as the cause of their fatigue [10], for markers of inflammation and other indicators of disease activity, an unclear and inconsistent relationship with fatigue in RA has been shown. Some studies, showing a significant relation, contrast other studies in which inflammatory markers did not contribute to the severity of fatigue at all [11, 12]. Although treatment with biologicals comes with reduction of fatigue in RA [9, 13], the actual group-level effects of biologicals on fatigue appears to be small [14]. Moreover, the reduction of fatigue is driven by improvements in pain and depression, and not by changes in inflammatory activity [15].

Our current understanding of the relation between fatigue in RA and disease activity is limited by the fact that, up to present, studies have been either small and cross-sectional or longitudinal with only a limited number of observations per patient [12]. Importantly, cross-sectional studies are by design only able to examine so-called “between-person” associations. As such, these studies only examined if patients with higher disease activity than others also experienced more fatigue. Listening to patients and their physicians, that fatigue and its relationship with RA differs between persons, demands for methodologies that can distinguish “between-person” from “within-person” associations. Such “within-person” relations over time describe what happens with fatigue within individual patients when their disease activity changes.

Most theories about the mechanisms that underlie specific associations between variables of interest, such as disease activity and fatigue, but also interventions targeting such variables, are based on processes that are assumed to take place within persons [16, 17]. So, they assume that changing one variable leads to changes in the other variable within people. Results from “between-person” analysis, such as those from cross-sectional studies, can only be generalized to “within-person” relations when strict assumptions of statistical “ergodicity” are met [18, 19]. However, it has been convincingly demonstrated that these assumptions are rarely met, and that “between-person” relations can be quite different from “within-person” relations both in magnitude and sometimes even in direction [16,17,18,19,20]: an observation referred to as Simpson’s paradox [21]. For instance, our study examining the association between disease activity and radiographic progression in RA patients showed that different indices of disease activity were not or only weakly associated at the “between-patient” level, but more often and more strongly associated within individual patients over time [22].

Cross-sectional or even standard longitudinal analyses do not allow for examining within-person associations, since the latter also mix both between-person and within-person results. Instead, specific statistical analysis methods of longitudinal data are needed that can distinguish the multiple sources of information, such as multilevel (hierarchical) mixed models [16, 17, 19, 20, 23, 24]. Although disaggregating “within-person” and “between-person” effects is increasingly used in other fields, it has been scarcely used in medicine and up to present not for studying the relationship between fatigue and disease activity in RA. More detailed knowledge on the type of association between different indicators of disease activity and fatigue may shed light on the apparent inconsistent relationships found in previous studies and is mandatory to develop a theoretical framework for fatigue in RA [12]. If between-person associations are indeed different from within-person associations, this can also have relevant implications for improving treatment of RA fatigue as it may allow future identification of individual patients or groups of patients with different patterns of associations between disease activity and fatigue.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore the “between-person” and “within-person” association of disease activity indices and fatigue severity in patients with established stable RA, who were asked to withdraw their treatment with a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi).

Methods

Patients and study design

Data were used from the Potential Optimalisation of Expediency and Effectiveness of TNFi’s (POET trial), registered in the Netherlands Trial Register (NTR3112) [25, 26]. Ethical approval for this multicenter study was granted by the Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects, region Arnhem—Nijmegen (Commissie Mensgebonden Onderzoek, regio Arnhem—Nijmegen). Local feasibility was approved by the Ethical Committees of all participating hospitals. In this pragmatic open-label trial, adult patients with established RA and stable low disease activity (28-joint Disease Activity Score [DAS28] < 3.2) for at least 6 months were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to stop or continue treatment with their current TNFi and followed up for one year. Concomitant treatment with conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs was continued. In case of flare (DAS28 ≥ 3.2 with an increase > 0.6) [27], TNFi could be restarted at the discretion of the rheumatologist. In total, 817 patients were included in the POET trial. All analyses in the current study were performed using the data from the discontinuation group (N = 531) since this treatment arm contained the most patients and more changes in both disease activity and fatigue was observed in this group over time.

Assessments

Patients’ disease activity was evaluated at the outpatient clinic by their treating rheumatologist and rheumatology nurse at baseline and at least every three months thereafter, for a period of one year. Additionally, patients completed patient-reported outcome measurements every three months, including fatigue.

Disease activity

Disease activity measurements included the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR, mm/hour), C-reactive protein level (CRP, mg/dl), 28 tender and swollen joint counts (TJC and SJC), and a patient-reported assessment of general health on a 100-mm visual analog scale (VAS-GH). ESR, joint counts and the VAS-GH were used to calculate the composite DAS28-ESR [28].

Fatigue severity

The Bristol RA Fatigue (BRAF) scales [29, 30] were used to measure different dimensions of fatigue at the defined timepoints. For compatibility with previous studies, that most used single-item scales for fatigue severity or intensity, the numerical rating scale for fatigue severity (BRAF-NRS Severity) was used for all analyses. The BRAF-NRS Severity measures the average level of fatigue during the past 7 days on an 0–10 NRS anchored by “no fatigue” (0) to “totally exhausted” [10]. The BRAF-NRS Severity scale has demonstrated both strong reliability and adequate sensitivity to change [31]. The patient acceptable symptom state for 0–10 fatigue NRSs has been estimated to be around 4 on average in different RA populations [32, 33].

Data analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26. Means of disease activity and fatigue scores were estimated and analysed using repeated measures linear mixed model analyses with time as a fixed covariate. Person-mean centering in combination with multilevel mixed modeling was used to separate within-patient associations between disease activity and fatigue from between-patient associations [17, 19, 20, 24]. For this, disease activity scores at each time-point were within-subject centered by subtracting the patient’s mean disease activity score across all available time-points from each observed value from that patient at the different time points. Within-subject centering effectively eliminates all between-subject variance, thus allowing to distinguish within-person effects from between-person effects in longitudinal models [17].

In the first series of models, observed disease activity values were entered as fixed time-varying covariates in repeated-measures linear mixed models with fatigue severity at each time point as dependent variable and patient intercept as random effect. In these models, the resulting regression estimate represents an aggregation (or unknow “blend”) of both the between-person and within-person effects of time-varying disease activity values on fatigue [17]. In the next series of models, person-mean disease activity (for between-person association) across all observations and time-varying person-mean centered disease activity at each observation (for within-person association) were simultaneously entered as fixed covariates. This procedure statistically separates any between-person association from within-person associations. The resulting person-mean regression estimate for disease activity indicates the extent to which patients’ mean disease activity scores are associated with fatigue (i.e., do patients with on average high disease activity report more severe fatigue at the different time points?). In contrast, the person-mean centered regression estimate indicates the extent to which patients’ deviations from their average (or typical) disease activity are associated with more or less fatigue at that that time point.

In all models person-mean centered disease activity scores, person-mean disease activity scores and fatigue severity scores were additionally converted to Z-scores to obtain standardized regression estimates (β) alongside unstandardized estimates from the mixed models. Standardized estimates were interpreted with Cohen’s [34] guidelines for small, medium, and large effect sizes (0.10, 0.30, and 0.50, respectively). Separate mixed models were estimated for composite DAS28-ESR scores and each of the individual disease activity parameters (ESR, CRP, TJC, SJC and VAS-GH) as fixed covariates. All models were estimated using the restricted maximum likelihood method and a compound symmetry covariance structure was used for the repeated measurements as this best fitted the data based on log-likelihood ratio tests across the different models. Between-patient and within-patient associations were illustrated using the ggplots2 package in R.

Results

Patient characteristics

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the patients included in the TNFi discontinuation group. Patients were mostly female with a mean age of 60 years and on average longstanding disease. Baseline disease activity was low (DAS28 < 3.2), and the majority of patients reported a BRAF-NRS fatigue severity score < 4.

Both disease activity scores (including all individual DAS-28 components) and fatigue scores significantly increased (all time effect p’s < 0.001) after stopping TNFi (Fig. 1). In total, 51.2% of the patients experienced a disease activity flare and almost half of the patients (47.5%) restarted their TNFi within 12 months after discontinuation.

Aggregate associations between disease activity and fatigue

Composite DAS28-ESR scores were significantly, but only weakly, associated over time in 'aggregated' (or blended) between- and within-patient analysis (β = 0.274, p < 0.0001). Aggregate associations for the separate parameters of disease activity were also weak for CRP and ESR values and the SJC and TJC, but medium for the VAS-GH (Table 2).

Disaggregated between-patient and within-patient associations

Disaggregated analysis showed that at the group level DAS28-ESR scores were significantly associated both between patients and within patients over time (Table 3). This indicates that patients with on average higher disease activity than other patients, also report more fatigue than other patients. In addition to this between-person effect, within individual patients increases in disease activity from their own mean were also associated with more severe fatigue.

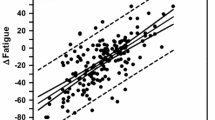

Both types of association were, however, only weak in magnitude. The low overall within-person association is illustrated in Fig. 2 (lower panel), showing a large variability in individual regression lines. Many patients showed strong positive associations between changes in disease activity and fatigue over time, but many patients also demonstrated no or even negative associations.

For the individual parameters of disease activity, a consistent difference between the objective and subjective parameters emerged (Table 3). Objective indicators of disease activity (CRP, ESR and SJC) were associated weakly within patients over time (β’s: 0.104–0.142, p’s < 0.0001), but not between patients. This indicates that changes in these markers in individual patients were associated with increased fatigue, but that patients with on average higher disease activity than other patients did not report more fatigue over time. In contrast, the TJC and VAS-GH were significantly associated both within and between patients, but with substantially stronger associations at the between-patient level. Especially the VAS-GH was strongly associated with fatigue between patients (β = 0.515, p < 0.0001) but only weakly within patients (β = 0.167, p < 0.0001). As with the composite DAS28-ESR scores, substantial individual differences were in the associations between separate disease activity parameters and fatigue (Fig. 3).

Between-person (left panel) and within-person (right panel) associations between individuals disease activity parameters and fatigue. ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate; SJC swollen joint count; TJC tender joint count; VAS-GH patient reported assessment of General Health on a 100 mm visual analog scale

Overall, the segregated analyses confirmed that DAS28-ESR scores and fatigue are weakly associated both between- and within patients over time, but that these associations are quite different for both different patients and for different components of disease activity.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that in RA patients disease activity is related to their fatigue. However, this relation is highly individual and may also be absent of negative in some patients. In addition, the relationship is different for the individual components of disease activity. Associations between subjective measures of disease activity and fatigue mostly reflect more stable between-patient differences, whereas objective markers of inflammation show significant positive associations only within patients.

Biomedically, a positive association between fatigue and disease activity can be explained by activity of the inflammatory process that comes with acute phase reactions and stimulation of cytokines and inflammatory cells. Also, fatigue in active RA can be the understandable consequence of the increased energy requirement in physical activities due to painful and swollen joints combined with muscle weakness [35]. From this pathophysiology, fatigue in RA patients with high disease activity can be reduced by successful suppression of inflammation. However, persistent fatigue in some RA patients with low levels of objective disease activity seems to suggest a mechanism independent from inflammation. It is hypothesized that several behavioral, psychological and cognitive mechanisms drive this process in a complex way [36]. This is reflected in a biopsychosocial model in which it is assumed that factors are to be involved to varying degrees in individual patients and that these factors influence each other in diverse ways in different patients. Physical functioning, poor mental status, sleep disturbance, pain, depression and anxiety have often been found to be independent variables associated with fatigue in multivariate analyses [37]. Hewlett et al. also proposed a dynamic model with bidirectional interactions between disease processes, cognitive and behavioural factors and personal life issues and assumed the influence of this factors to vary between individuals and within individuals at different times [38].

The use of different (composite) indicators of disease activity and analyses, which do not distinguish between associations between persons and within persons, may have led to the conflicting results in earlier research. The results of the analysis used in our study, which separate between-patients and within-patients associations, may explain why these previous studies generally found either weaker or contradictory associations between disease activity and fatigue. In our study, we included the results of the aggregated and disaggregated analysis to show what happens when within-person and between-person associations are statistically separated. The results confirm the varying relationship between different disease activity measures and fatigue both between and within individuals. Our study shows a weak significant association between fatigue and the objective components of disease activity, e.g., inflammation, within individuals and even no significant association of these factors between individuals. Additionally, we have clearly illustrated that the within person association between inflammation and fatigue varies widely between individual patients from strong and positive to absent or even negative.

The stronger association between fatigue and the subjective components of disease activity, e.g., tender joints and general health, between persons may, although not directly inferred from the current study, support the idea that fatigue may be a more common symptom of chronic disease rather than a disease-specific symptom. In particular, patients’ perceived general health will to some extent depend on factors that are not always disease specific. Menting et al., already demonstrated that variance in fatigue severity in different chronic diseases, including RA, can largely be explained by non-disease-specific factors like sex, age, motivational and concentration problems, pain, sleep disturbance, physical functioning, reduced activity and lower self-efficacy [39]. They therefore argued for a transdiagnostic approach that focuses on the individual patient’s needs.

Given the various disease-specific and non-disease-specific factors that influence fatigue, the approach to this important patient reported symptom will have to be multidimensional. Proper multidimensional management of fatigue starts by making it an important topic for discussion during the consultation between patient and healthcare professional. Although many patients report fatigue as a major symptom, it is not structurally communicated at the rheumatology outpatient clinic. It has been demonstrated that fatigue was communicated in only 6% of the total consultation time and that in most cases the patient initiated the communication on fatigue mostly using cues to express their worries instead of communicating their concerns directly [40]. As a result, healthcare professionals will have an important role in communicating about fatigue and recognizing concerns that are indirectly reported by patients.

Our study was subjected to some strengths and weaknesses [25]. The cohort used for this study was one of the largest studies in real life, where prospectively and stringently, disease activity as well as fatigue was measured after stopping one of the most successful anti rheumatic therapies, i.e., TNFi, while being in remission. Consequently, flares with changes in fatigue and disease activity could be expected. Our statistical approach proved suitable to disentangle and illustrate variation between two or more variables in different individuals, providing a more detailed insight than standard cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. One of the limitations of our study is that flares in the POEET cohort where immediately followed by restart of TNFi, so major and long-lasting flares are rare. However, the data as they are with mostly mild and short flares clearly illustrated the overall and individual associations between the different indices of disease activity and fatigue. Major and long-lasting flares would likely only have strengthened this conclusion.

Our study was explorative in design as a first demonstration that the relation between disease activity and fatigue is different in individual patients. Future research may focus on the possible reasons for these differences and on identifying groups of patients with the same or absent associations. Now that most patients with RA are able to achieve remission, fatigue remains one of the most debilitating symptom for some patients. We believe, that our data support the need for a more personalized approach to further improve the management of fatigue in RA. Optimal anti-inflammatory treatment may need to be combined with neuro-psychological interventions based upon the needs of individual RA-patients. Many personal factors, which healthcare providers may not always know or be able to influence, will contribute to varying degrees to fatigue in RA patients. Differences in associations between disease activity and fatigue between different patients must be first recognized before knowledge and interventions in this area can be improved. RA patients suffering from fatigue sometimes, but not always, have high disease activity and therefore do not always need more or different medication. But they will all need to be approached and advised with respect and to the best of our knowledge.

Conclusion

Our results show that in some patients inflammatory disease activity and fatigue are related, while in other patients this association seems absent. More research on the complex relation between disease activity and fatigue in RA and other inflammation driven diseases is necessary, but our results point to the need for a more individually targeted approach of fatigue in RA, both in research and daily clinical practice.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are not publicly available due to legal and ethical reasons but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- RA:

-

Rheumatoid arthritis

- DAS-28:

-

Disease activity score in 28 joints

- TNFi:

-

Tumor Necrosis Factor inhibitor

- ESR:

-

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- TJC:

-

Tender joint count

- SJC:

-

Swollen joint count

- VAS-GH:

-

Patient-reported assessment of general health on a 100-mm visual analog scale

- DAS28-ESR:

-

Disease activity score in 28 joints including the erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- BRAF-NRS:

-

Bristol Rheumatoid Arthritis Fatigue-Numerical Rating Scale

- RF:

-

Rheumatoid factor

- Anti-CCP:

-

Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide

References

Wolfe F, Hawley DJ, Wilson K. The prevalence and meaning of fatigue in rheumatic disease. J Rheumatol. 1996;23(8):1407–17.

Overman CL, Kool MB, Da SJAP, Geenen R. The prevalence of severe fatigue in rheumatic diseases : an international study. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:409–15.

Hewlett S, Cockshott Z, Byron M, Kitchen K, Tipler S, Pope D, et al. Patients’ perceptions of fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: overwhelming, uncontrollable, ignored. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53(5):697–702.

Hewlett S, Carr M, Ryan S, Kirwan J, Richards P, Carr A, et al. Outcomes generated by patients with rheumatoid arthritis: How important are they? Musculoskeletal Care. 2005;3(3):131–42.

Sanderson T, Morris M, Calnan M, Richards P, Hewlett S. Patient perspective of measuring treatment efficacy: the rheumatoid arthritis patient priorities for pharmacologic interventions outcomes. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62(5):647–56.

Kirwan JR, Minnock P, Adebajo A, Bresnihan B, Choy E, de Wit M, et al. Patient perspective: fatigue as a recommended patient centered outcome measure in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(5):1174–7.

Aletaha D, Landewe R, Karonitsch T, Bathon J, Boers M, Bombardier C, et al. Reporting disease activity in clinical trials of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: EULAR/ACR collaborative recommendations. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(10):1360–4.

Repping-Wuts H, van Riel P, van Achterberg T. Rheumatologists’ knowledge, attitude and current management of fatigue in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27(12):1549–55.

Verstappen SMM. Outcomes of early rheumatoid arthritis—the WHO ICF framework. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013;Vol. 27:555–70.

Repping-Wuts H, Uitterhoeve R, van Riel P, van Achterberg T. Fatigue as experienced by patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA): A qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008;45(7):995–1002.

Stebbings S, Treharne GJ. Fatigue in rheumatic disease: an overview. Int J Clin Rheumtol. 2010;5(4):487–502.

Nikolaus S, Bode C, Taal E, van de Laar MAFJ. Fatigue and factors related to fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65(7):1128–46.

Bergman MJ, Shahouri SS, Shaver TS, Anderson JD, Weidensaul DN, Busch RE, et al. Is fatigue an inflammatory variable in rheumatoid arthritis (RA)? Analyses of fatigue in RA, osteoarthritis, and fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(12):2788–94.

Chauffier K, Salliot C, Berenbaum F, Sellam J. Effect of biotherapies on fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51(1):60–8.

Pollard LC, Choy EH, Gonzalez J, Khoshaba B, Scott DL. Fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis reflects pain, not disease activity. Rheumatology. 2006;45(7):885–9.

Hoffman L, Stawski RS. Persons as contexts: evaluating between-person and within-person effects in longitudinal analysis. Res Hum Dev. 2009;6(2–3):97–120.

Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. The disaggregation of within-person and between-person effects in longitudinal models of change. Annu Rev Psychol. 2011;62(1):583–619.

Hamaker EL. Why researchers should think “within-person”: a paradigmatic rationale. In: Handbook of research methods for studying daily life. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2012. p. 43–61.

Wang LP, Maxwell SE. On disaggregating between-person and within-person effects with longitudinal data using multilevel models. Psychol Methods. 2015;20(1):63–83.

van de Pol M, Wright J. A simple method for distinguishing within- versus between-subject effects using mixed models. Anim Behav. 2009;77(3):753–8.

Kievit RA, Frankenhuis WE, Waldorp LJ, Borsboom D. Simpson’s paradox in psychological science: a practical guide. Front Psychol. 2013;4:513.

ten Klooster PM, Versteeg LGA, Oude Voshaar MAH, de la Torre I, De Leonardis F, Fakhouri W, et al. Radiographic progression can still occur in individual patients with low or moderate disease activity in the current treat-to-target paradigm: real-world data from the Dutch Rheumatoid Arthritis Monitoring (DREAM) registry. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21(1):237.

Hoffman L. Multilevel models for examining individual differences in within-person variation and covariation over time. Multivar Behav Res. 2007;42(4):609–29.

Hox JJ, Moerbeek M, van de Schoot R. Multilevel analysis: techniques and applications. Third. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis; 2017.

Ghiti Moghadam M, Vonkeman HE, Ten Klooster PM, Tekstra J, van Schaardenburg D, Starmans-Kool M, et al. Stopping tumor necrosis factor inhibitor treatment in patients with established rheumatoid arthritis in remission or with stable low disease activity: a pragmatic multicenter, open-label randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheumatol (Hoboken, NJ). 2016;68(8):1810–7.

Ghiti Moghadam M, ten Klooster PM, Vonkeman HE, Kneepkens EL, Klaasen R, Stolk JN, et al. Impact of stopping tumor necrosis factor-inhibitors on rheumatoid arthritis patients’ burden of disease. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2018;70(4):516–24.

van der Maas A, Lie E, Christensen R, Choy E, de Man YA, van Riel P, et al. Construct and criterion validity of several proposed DAS28-based rheumatoid arthritis flare criteria: an OMERACT cohort validation study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(11):1800–5.

Prevoo MLL, Van’T Hof MA, Kuper HH, Van Leeuwen MA, Van De Putte LBA, Van Riel PLCM. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight-joint counts development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38(1):44–8.

Nicklin J, Cramp F, Kirwan J, Greenwood R, Urban M, Hewlett S. Measuring fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: a cross-sectional study to evaluate the Bristol Rheumatoid Arthritis Fatigue Multi-Dimensional questionnaire, visual analog scales, and numerical rating scales. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62(11):1559–68.

Hewlett S, Kirwan J, Bode C, Cramp F, Carmona L, Dures E, et al. The revised Bristol Rheumatoid Arthritis Fatigue measures and the Rheumatoid Arthritis Impact of Disease scale: validation in six countries. Rheumatology. 2018;57(2):300–8.

Dures EK, Hewlett SE, Cramp F a, Greenwood R, Nicklin JK, Urban M, et al. Reliability and sensitivity to change of the Bristol Rheumatoid Arthritis Fatigue scales. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2013;52(10):1832–9.

Duarte C, Santos E, Kvien TK, Dougados M, de Wit M, Gossec L, et al. Attainment of the Patient-acceptable Symptom State in 548 patients with rheumatoid arthritis: Influence of demographic factors. Jt Bone Spine. 2021;88(1):4–7.

Puyraimond-Zemmour D, Etcheto A, Fautrel B, Balanescu A, de Wit M, Heiberg T, et al. Associations between five important domains of health and the patient acceptable symptom state in rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis: a cross-sectional study of 977 patients. Arthritis Care Res. 2017;69(10):1504–9.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

Evans WJ, Lambert CP. Physiological basis of fatigue. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;86(1 SUPPL.):29–46.

Katz P. Causes and consequences of fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2017;29(3):269–76.

Geenen R, Dures E. A biopsychosocial network model of fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Rheumatol (United Kingdom). 2019;58:V10-21.

Hewlett S, Chalder T, Choy E, Cramp F, Davis B, Dures E, et al. Fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: time for a conceptual model. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50(6):1004–6.

Menting J, Donders R, Fortuyn HAD, Knoop H. Is fatigue a disease-specific or generic symptom in chronic medical conditions ? Heal Psychol. 2018;37(6):530–43.

Repping-Wuts H, Repping T, van Riel P, van Achterberg T. Fatigue communication at the out-patient clinic of rheumatology. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76(1):57–62.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all patients, rheumatology nurses and rheumatologists from all centers who participated in the POET study. The authors thank the Dutch Society for Rheumatology that initiated the POET study and the Dutch organization for health research and healthcare innovations for funding the POET study on behalf of the Dutch Ministry of Health.

Funding

No specific funding for the current study. The POET study was funded by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (Project Number 152041002) on behalf of the Dutch Ministry of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors significantly participated in the preparation of the manuscript. GV and PtK drafted the first version of the manuscript. PtK performed the statistical analysis. MvdL revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors participated in the interpretation of the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Data were used from the POET study, a pragmatic randomized multicenter open-label controlled trial. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects, region Arnhem—Nijmegen (Commissie Mensgebonden Onderzoek regio Arnem—Nijmegen). Local feasibility was approved by the Ethical Committees of all participating hospitals. The study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all study patients.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Versteeg, G.A., ten Klooster, P.M. & van de Laar, M.A.F.J. Fatigue is associated with disease activity in some, but not all, patients living with rheumatoid arthritis: disentangling “between-person” and “within-person” associations. BMC Rheumatol 6, 3 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41927-021-00230-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41927-021-00230-2