Abstract

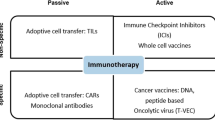

Recent immunotherapeutic approaches have evolved as powerful treatment options with high anti-tumour responses involving the patient’s own immune system. Passive immunotherapy applies agents that enhance existing anti-tumour responses, such as antibodies against immune checkpoints. Active immunotherapy uses agents that direct the immune system to attack tumour cells by targeting tumour antigens. Active cellular-based therapies are on the rise, most notably chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy, which redirects patient-derived T cells against tumour antigens. Approved treatments are available for a variety of solid malignancies including melanoma, lung cancer and haematologic diseases. These novel immune-related therapeutic approaches can be accompanied by new patterns of response and progression and immune-related side-effects that challenge established imaging-based response assessment criteria, such as Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid tumours (RECIST) 1.1. Hence, new criteria have been developed. Beyond morphological information of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging, positron emission tomography (PET) emerges as a comprehensive imaging modality by assessing (patho-)physiological processes such as glucose metabolism, which enables more comprehensive response assessment in oncological patients. We review the current concepts of response assessment to immunotherapy with particular emphasis on hybrid imaging with 18F-FDG-PET/CT and aims at describing future trends of immunotherapy and additional aspects of molecular imaging within the field of immunotherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Key points

-

Novel response criteria are incorporating positron emission tomography (PET) imaging to assess immunotherapy efficacy.

-

PET-based response criteria refine the assessment of response to immunotherapy.

-

PET can assist in detecting immune-related side effects.

-

Novel PET-ligands targeting molecules in immune-related pathways are under development.

Background

Recent immunotherapeutic approaches have emerged as powerful treatment options with high anti-tumour responses. These effects can be achieved by redirecting, stimulating, or genetically reprogramming the patient’s own immune system to target cancer cells. Passive immunotherapy is the most frequent form of immunotherapy, involving agents that enhance existing anti-tumour responses, such as antibodies against immune checkpoints such as cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), programmed cell death protein (1 PD-1), and programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1). Active immunotherapy uses agents that direct the immune system to attack tumour cells by targeting tumour antigens (e.g., vaccines such as Bacillus Calmette–Guérin in bladder cancer). Active cellular-based therapies are on the rise, most notably chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy, which redirects patient-derived T cells against tumour antigens [1,2,3].

These approaches are accompanied by novel patterns of response and progression, as clinical phenomena such as pseudoprogression or hyperprogression occur [4]; moreover, new aspects and manifestations of (immune-related) side-effects to systemic treatments can be observed [5]. Beyond these clinical features, current immunotherapeutic approaches do also challenge previously established imaging approaches based on computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging. Beyond the assessment of the mere morphological extent, positron emission tomography (PET) imaging has emerged as comprehensive imaging modality by assessing (patho-)physiological processes and their changes to particular systemic treatments. Hence, combined hybrid imaging can highly influence the initial staging and the further clinical patient management in a high proportion of patients compared to morphological imaging only [6], as is currently for the clinical management of Hodgkin lymphoma [7].

This narrative work reviews the current concepts of response assessment to immunotherapy with a particular emphasis on combined hybrid imaging using 18F-FDG PET/CT and aims at describing future trends of immunotherapy and additional aspects of molecular imaging within the field of immunotherapy.

Immunotherapy: the state of the art

The idea of utilising immune cells to eradicate malignant disease dates back to 1970, when Buckner et al. [8] reported the first successful allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in a patient suffering from leukaemia. This technique grew to become an indispensable means of treatment for many forms of haematologic malignancies. In contrast, recent immunotherapeutic approaches aim to achieve anti-tumour responses by redirecting, stimulating, or genetically reprogramming the patient’s own immune system to target cancer cells. These strategies include antibody-based treatments, immune checkpoint inhibitors, and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cells as most prominent examples.

Monoclonal antibodies offer the opportunity to therapeutically target specific tumour-associated antigens. By opsonisation, they enable effector cells such as natural killer cells [9], phagocytes [10, 11], and the complement system [12] to kill the respective target cells. Rituximab, targeting the cluster of differentiation (CD) 20 protein, is the most common agent and became essential for clinical routine since its approval in 1998 by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for the treatment of haematologic B cell malignancies.

Checkpoint inhibitors

Checkpoint inhibitors count among the most ground-breaking therapeutic approaches to have been translated into clinical use. The discovery of their underlying mode of action has been awarded with the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2018. The programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) protein, its corresponding programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) represent immune checkpoints that are targeted in clinical practice. PD-L1 is often overexpressed in tumour cells and interacts with the membrane bound PD-1 on T cells, thus inhibiting T cell responses [1]. CTLA-4 is located intracellularly in resting T cells and translocates to the cell surface upon engagement of the T cell receptor, inhibiting activation of the T cell by competing for essential costimulatory binding sites and via inhibitory signalling [13]. Several checkpoint inhibitors have been approved for clinical use by the EMA and the United Stated Food and Drug Administration, first being Ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4) in 2011, followed by others such as Nivolumab and Pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1).

Bispecific T cell engagers and CAR-T cell therapy

Antibody therapies have advanced over time and recently the concept of bispecific antibodies or “bispecific T cell engagers” came into the spotlight, as the first bispecific T cell engager, Blinatumomab, was approved by the EMA in 2015 for use in relapsed or refractory B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. This antibody is composed of two single-chain variable fragments targeting CD19 or CD3, respectively [14]. The bispecific nature of the antibody allows to bring tumour and immune effector cells into close proximity, facilitating the induction of immune cell mediated apoptosis [15].

CAR-T cells constitute the latest breakthrough in clinical immuno-oncology, with the two CAR-T cell products Yescarta (axicabtagene ciloleucel) and Kymriah (tisagenlecleucel) receiving approval by the EMA in August 2018, shortly after approval in the USA. The treatment is based on genetic modification of patient-derived T cells, obtained by leukapheresis, followed by their reinfusion into the patient. The cells are equipped with artificial CARs, which are composed of an antibody-derived single-chain variable fragments, a transmembrane and a signalling domain [16]. The single-chain variable fragment allows recognition of surface bound tumour-associated antigens such as CD19, whereas physiological T cell receptors are restricted to recognition of antigen fragments presented via the major histocompatibility complex [2]. Upon antigen binding, the CAR induces activation, proliferation of and cytokine release by the T cells, followed by cytotoxic activity targeted against the respective cancer cells. So far, the EMA approval covers therapeutic use in relapsed or refractory diffuse large B cell lymphoma, primary mediastinal large B cell lymphoma (Yescarta) and B cell Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (Kymriah).

The consequences of CAR-T cell approval for clinical reality are remarkable, as the overall response rates for Kymriah during pivotal studies in patients suffering from relapsed or refractory diffuse large B cell lymphoma reached 52%, with 40% of the patients experiencing a complete response (CR), of whom 79% would remain relapse-free after 12 months of follow-up [17]. Yescarta demonstrated comparable efficacy with an objective response rate of 82% and a CR rate of 40% after a median follow-up time of 15.4 months [18, 19]. The endpoint for both pivotal studies had been set at best overall response in more than 20% of patients, a value based on data of historical studies. The significance at which this endpoint was met implies the overwhelming impact the approval had on the perspective of lymphoma patients relapsing from initial treatment regimens.

Conventional imaging: pseudoprogression and hyperprogression

Standardised assessment of change in tumour burden is essential in the evaluation of therapies in cancer patients. Most clinical trials use tumour shrinkage (objective response) or development of progressive disease (PD) as endpoints and continuation or modification of therapy regimens depend on it. The Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid tumours (RECIST) guidelines were introduced by an international working group in 2000 [24] and revised in 2009 as RECIST 1.1 [20, 25]. RECIST is primarily based on the use of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (Table 1). These criteria have been successfully validated in many studies, and today, most clinical trials on cancer therapies use them to evaluate objective tumour response even though, compared with chemotherapeutic drugs, tumours respond differently to newer drugs with other target mechanisms such as immunotherapeutics. Atypical response patterns such as pseudoprogression (where the tumour burden increases initially due to an increase in lesion size and/or occurrence of newly detectable tumour lesions with subsequent decrease in tumour burden) may lead to incorrect determination of the response status using RECIST [26].

Since tumour growth or newly detectable tumour lesions are generally classified as PD based on RECIST, pseudoprogression is not diagnosed correctly and may result in an erroneous discontinuation of treatment or an unjustified exclusion of patients from clinical trials. To address this, the RECIST working group developed a modified guideline for response assessment to immunotherapy in 2017, called Immune RECIST (iRECIST) [23]. It is based on RECIST 1.1 guidelines and essentially has a new category of immune unconfirmed progression disease that requires to be confirmed by an additional, early follow-up scan within six to eight weeks. Immune unconfirmed progression disease should be considered carefully, as an increase in tumour size is still more likely to be true progression rather than pseudoprogression. The frequency of pseudoprogression varies between different tumour entities and is most frequently observed in melanoma patients (up to 13%) [21, 27]. Notably, in iRECIST, the target response drives the timepoint response after patients had immune unconfirmed progressive disease. For example, new lesions develop on follow-up 1 and persist or have not fully disappeared in follow-up 2. Yet, the target lesion sum on follow-up 2 has then regressed to a partial response (PR) level compared to baseline (in the absence of any other manifestations of PD). This is considered overall immune partial response, not continued immune unconfirmed PD.

Another atypical response pattern related to immunotherapy is hyperprogression, a term with various definitions, meaning a pronounced acceleration of tumour growth [28,29,30]. If hyperprogression is suspected, treatment must be interrupted immediately, even though robust biomarkers are still pending. Beyond iRECIST, several other refined response criteria using morphological information were developed (see Table 1).

PET/CT imaging of immunotherapy

18F-FDG PET-based response assessment criteria

In 1999, the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer’ (EORTC) first introduced PET-based, metabolic information in specified criteria for the response assessment of oncological diseases in general [31]. Of note, those were also the first PET-based criteria to be applied for monitoring of immunotherapy [32]. These EORTC criteria were then superseded by the PET Response Criteria in Solid tumours (PERCIST) published by Wahl et al. in 2009 [33]. Despite rather comparable classifications, PERCIST introduced the SUL—which is the standardised uptake value (SUV) corrected for the lean body mass—as an imaging parameter and made a tumour SUL 1.5-fold higher than the SUL of the non-affected liver a prerequisite for an evaluable lesion. Moreover, the SULpeak is assessed within a spherical volume of interest in the site of the most metabolically active tumour manifestation.

In 2017, Cho et al. [34] prospectively compared different response criteria in a small set of patients undergoing immunotherapy in order to evaluate an optimised complementary fit between morphological and metabolic response parameters. The best combination of the assessed parameters were then transformed in new criteria and named PET/CT Criteria for Early Prediction of Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy (PECRIT) [34]. Additional response criteria were suggested by the Heidelberg group by introducing PET Response Evaluation Criteria for Immunotherapy (PERCIMT), which moreover take into account the clinical relevance of the absolute amount of new lesions during immunotherapy [35, 36]. For an overview, please see Table 2.

When dealing with lymphomas, specific criteria for response assessment were established. In 1999, the first standardised response criteria for lymphoma were introduced [37]. However, the issue of residual morphological masses remained unsolved. Hence, in 2007, Cheson criteria incorporated PET imaging for 18F-FDG-avid lymphomas [38]. Based on the First International Workshop on PET in Lymphoma in Deauville, France, a newly established 5-point scale (i.e., the Deauville score) relative to blood-pool and liver activity (see Table 3) was introduced [39] and, as a consequence, was incorporated in the subsequent Lugano criteria in 2014 [40], which succeeded the Cheson criteria. In general, a Deauville score 1–3 during therapy is considered as CR, whereas a score 4–5 at the termination of treatment is considered a non-response.

In the light of immunotherapy, modified Lugano criteria (lymphoma response to immunomodulatory therapy criteria (LYRIC)) were proposed in 2016 to account for features specific for immunotherapy [41]. Here, the category indeterminate response (IR) was introduced when an increase of tumour burden, new lesions, or an increase of 18F-FDG-avidity is observed, leading to a consequent follow-up imaging study within twelve weeks in order to rule out or confirm PD or pseudo-progression [41].

Most recently, in 2017, Response Evaluation Criteria in Lymphoma (RECIL) were established by an international working group [42]. RECIL aimed at homogenising response assessing in trials by modifying response criteria. Within this process, the role of 18F-FDG PET was reduced in favour of a more pronounced impact of CT-based changes, considering the potential alteration of glucose metabolism by immunomodulatory drugs that may obscure the tumour 18F-FDG-avidity [42]. In Table 4, an overview of response criteria for lymphoma is provided.

Response assessment to immunotherapy with 18F-FDG PET

PET imaging was initially used for immunotherapy monitoring in patients with solid tumours. Given the early and successful implementation of immunotherapy within the clinical workup of melanoma patients, the first PET-based response assessment using EORTC criteria was applied in melanoma patients [32]. Already at this early stage, the appearance of new lesions was not linked to progressive disease per se leading to potential misclassifications. Residual metabolic activity on 18F-FDG PET (similarly to the Deauville score assessment) in melanoma patients treated with anti-PD-1 agents was also associated with residual vital tumour masses. Vice versa, a loss of 18F-FDG-avidity despite remaining morphological masses was associated with improved outcome; however, remaining residual 18F-FDG-avidity despite clinical response was also observed, possibly due to immune infiltrates [43].

In a cohort of melanoma patients undergoing immunotherapy, several morphological and functional response assessment criteria were applied, but only a limited agreement among the applied criteria in terms of outcome prediction was observed. Hence, the combination of parameters best suitable for prediction was established (PECRIT criteria) [34]. When dealing with immunotherapy using ipilimumab in melanoma, the Heidelberg group demonstrated that changes of SUV-based parameters in the disease course do not predict the individual outcome, whereas the number of new lesions and their extent during therapy was predictive for clinical outcome and allowed proper stratification [35] (see also Table 4).

As a consequence, PERCIMT criteria were also used for interim evaluation in melanoma patients undergoing immunotherapy and compared to EORTC criteria by stratifying patients with metabolic benefit (i.e., CR, PR, or SD) and those without (i.e., PD). Again, agreement of PERCIMT and EORTC was limited; although PERCIMT showed a significantly higher sensitivity for the prediction of clinical benefit than EORTC, both criteria were equally able to predict the absence of clinical benefit [36]. Hence, a recent position paper by the European Association of Nuclear Medicine critically discussed the added value of the PERCIMT criteria. Firstly, study conclusions were based on 41 patients only and secondly, EORTC criteria showed even slightly higher diagnostic performance for the detection of a missing clinical benefit compared to PERCIMT, without reaching the level of significance [35].

Beyond melanoma, a few studies have addressed the value of 18F-FDG PET imaging of non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) patients undergoing immunotherapy. Here, 18F-FDG changes in terms of PERCIST criteria (compared to RECIST 1.1) were highly predictive for treatment efficacy in NSCLC patients undergoing nivolumab therapy even at an early stage of 1 month after treatment initiation and was shown to be an independent prognostic factor at multivariate analysis [44]. Also, response on 18F-FDG PET (using EORTC criteria) in NSCLC patients undergoing atezolizumab therapy 6 weeks after initiation were predictive for the further morphological disease course on CT. Moreover, even patients with pseudoprogression could be identified by using 18F-FDG PET [45]. In addition, follow-up 18F-FDG PET imaging in patients classified as PD on PERCIST criteria was able to identify patients with pseudoprogression and immune dissociated-response in more than half of patients previously classified as PD. Importantly, improved clinical outcome was observed in these patients [46].

When dealing with haematologic malignancies, first reports of anti-PD1-therapy in Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) were published already in 2014 [47], where a combination of CT and PET/CT imaging was used in order to assess response to immunotherapy. The KEYNOTE-013 trial [48] applied the Cheson 2007 criteria [38]. These and their updated 2014 version, the Lugano criteria [40], were subsequently applied in several trials evaluating immunotherapy in HL [49,50,51,52,53], partly also in comparison to LYRIC criteria [54, 55].

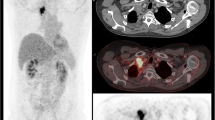

Initially, the metabolic changes over time in patients with relapsed or refractory HL undergoing anti-PD-1-treatment were described by Dercle et al. [56]. Subsequently, the same group demonstrated that a decrease of 18F-FDG-avidity in tumour and spleen as well as the general 18F-FDG-avid tumour burden 3 months after initiation of anti-PD-1-treatment were associated with improved clinical outcome [55]. Consequently, CT-based response evaluation had to be reclassified when additionally applying PET criteria in 44% of HL patients undergoing nivolumab. Among these, the majority showed complete metabolic response in contrast to CT (Fig. 1) with improved clinical outcome [57]. In the setting of early treatment response of HL and anti-PD-1-treatment, both Lugano criteria and LYRIC performed equally with equivocal findings [58], a result that possibly relates to the rather rare occurrence of pseudoprogression in HL [55, 56, 59].

With regard to PET/CT imaging in CAR-T cell therapy, only limited data is available. Firstly, Shah et al. [60] demonstrated in a small set of diffuse large B cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma that patients with complete remission of the metabolic tumour volume on 18F-FDG PET 4 weeks after CAR-T cell therapy showed a long-term remission over 2 years and patients with remaining activity had an early relapse. Secondly, Wang et al. [61] showed that a higher 18F-FDG-avid tumour burden prior to therapy was associated with more severe CAR-T cell therapy-related side effects. Interestingly, this study also demonstrated that the phenomenon of pseudoprogression and local immune activation can also occur in patients undergoing CAR-T cell therapy (Fig. 2). Of note, several trials are underway evaluating the particular contribution of PET imaging in the course of CAR-T cell therapy (e.g., NCT03086954, NCT02476734).

A patient example with pseudoprogression of diffuse large B cell lymphoma undergoing chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cell therapy. Eight weeks after reinfusion of CAR-T cells, numerous abdominal lymph nodes with highly increased metabolism occurred, but fully resolved in the further disease course without additional treatment

So far, there is only limited literature dealing with the very exact clinical value of PET/CT imaging for the identification of pseudo-progression in patients undergoing immunotherapy. One study in melanoma patients suggests that the new appearance of ≥ 4 metabolically active lesions with a functional diameter < 1.0 cm or ≥ 3 lesions > 1.0 cm is associated with real progression rather than the occurrence of pseudoprogression [35]. Another study identified that true progression was associated with a larger increase of metabolic tumour volume than pseudoprogression at the time of first follow-up [62]. More recent data indicated that metabolic changes of primary and secondary lymphoid organs during the course of immunotherapy in melanoma patients are associated with therapy response [63]; hence, these changes of lymphoid organs such as the spleen could potentially be useful for the differentiation of pseudo-progression and real progression. These interesting findings should be explored in further studies to assess their diagnostic value for early identification of patients with pseudoprogression.

Imaging of immune-related adverse events

During the application of immunotherapeutic agents, there is a reactivation of the immune system that not only has anti-tumour effects, but also might affect healthy tissue leading to new toxicity profiles that require a different management than the toxicity of chemotherapies [64, 65]. These new immune-related adverse events (irAE) present with a broad variety of symptoms and might affect a multitude of organs. Most commonly, the cutaneous, gastrointestinal and endocrine systems are affected. However, some differences and diverging patterns of clinical manifestations can be observed depending on the checkpoint inhibitor and immunotherapy subgroups [66]. Nonetheless, a rapid identification of irAEs can improve the clinical outcome, as most of these irAEs are treated with subsequent systemic immunosuppression [67, 68].

The occurrence of irAEs can also affect response assessment with PET, as inflammatory reactions accompany these irAEs consequently leading to an elevated 18F-FDG-avidity [69], which might lead to a misinterpretation of the respective PET study. However, a certain adaptation of 18F-FDG-avidity can be observed over time [70, 71]. Vice versa, this 18F-FDG-avidity of irAEs also enables an exact localisation and identification [72], which gains further importance in the light of the association of occurrence of irAEs and the effectiveness of immunotherapy in melanoma and NSCLC patients [5, 73].

Recently, the report from the European Association of Nuclear Medicine symposium on immunotherapy stated that incidental findings related to irAEs should be reported. Although irAEs might not necessarily be associated with clinical symptoms, clinicians should be aware of their presence and ensure clinical monitoring, which, however, might lead to a clinical intervention. First signs of elevated immune activity can be seen as spleen enlargement and/or elevated uptake leading to an inversion of the liver-to-spleen uptake ratio. Also, reactive lymph nodes might be observed in the direct drainage of the tumour. However, these findings have to be compared to the respective baseline scan to assess their pathophysiological relevance, but also to safely relate these findings to the immunotherapy [74]. Moreover, the occurrence of immune-related sarcoid-like reactions consisting of lymphadenopathy and pulmonary granulomatosis with elevated glucose consumption have to be kept in mind [75]. This is also the most relevant irAE that may be misinterpreted as progression by mimicking newly developed mediastinal and hilar lymph node manifestations. The discordant course of other manifestations and the symmetry of these changes are helpful for the differentiation from malignant lesions (Fig. 3).

In CAR-T cell therapy, there is, however, another set of rather immediate adverse effects, such as cytokine release syndrome, CAR-T cell-related neurologic toxicities, and B cell aplasia, which are not directly detectable using 18F-FDG-PET [61, 76, 77]. Moreover, CAR-T cell-related adverse events occur even earlier than irAEs, even hours and days after the first application. In sum, there is only a small amount of literature describing late toxicities different from irAEs so far [78, 79]. Hence, more clinical experience and, in particular, literature evaluating the use of PET imaging in CAR-T cell therapy are needed.

Future directions

Novel treatments

Despite growing success, immunotherapy, adoptive cell therapy in particular, still face many challenges. As the scientific community remains in search for answers as to why significant fractions of patients remain nonresponsive to immunotherapy, new targets for cellular treatments are validated in a fast-growing number of clinical trials.

In the context of haematologic malignancies, these new approaches include CAR-T cells targeted against B cell maturation antigen in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma [80, 81] and CAR-T cells targeted against CD22 in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, last of which managed to achieve stunning CR rates of over 80% in patients treated at the highest-dose level in a phase I trial [3, 82]. Further, CAR-T cells are evaluated in multiple phase I and II trials for use in solid malignancies such as mesothelioma, metastatic pancreatic, gastric and prostate cancers, glioblastoma, sarcoma, and others [83].

Another emerging concept in cellular immunotherapy is universal or adapter CAR-T cells. The single-chain variable fragments of these CARs are designed to recognize antigens which are physiologically not present on the surface of tumour or healthy cells [84]. Application of tumour-specific ligands linked to such antigens allows them to serve as an adapter between the universal CAR and the respective tumour cell. This enables targeting of a broad variety of tumour antigens simultaneously or sequentially and without the need to engineer CAR-T cells for every single tumour under consideration, while at the same time providing better control of CAR-T cell activity [85, 86].

Taking the idea of universal immune cells further, recent reports demonstrate the potential of CAR-transduced natural killer cells to combat lymphoma in a combined phase I and II trial [87]. Interestingly, natural killer cells do not mediate graft-versus-host-disease due to their lack of endogenous T cell receptors, allowing human leukocyte antigen mismatched transfusions [3]. These early data suggest that an off-the-shelf CAR product may be within reach, which eventually will be necessary to enable broad availability and affordability.

Novel ligands for nuclear imaging

Beyond morphological and glucose-based imaging, new molecular radiotracers arise that directly target the key molecules of immune checkpoint pathways and immune responses [88, 89]. Anti-PD-1 antibodies can be labeled with 89Zr or 64Cu and are suitable for in vivo imaging PD-1-expressing tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes [89], which might be an interesting approach for the non-invasive visualisation and quantification of PD-1-expression, as immunohistochemical analyses are limited by the heterogeneous tissue expression on biopsies or single tissue specimen [90].

First studies were already performed in humans. Niemeijer et al. [91] published a study using radiolabeled anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody 89Zr-nivolumab in patients with advanced NSCLC and showed a significant 89Zr-nivolumab tumour uptake, that was higher in patients with immunohistochemically proven PD-1 positive tumour-infiltrating immune cells as compared with PD-1 negative tumours. Interestingly, PD-(L)1 PET-CT demonstrated highly heterogeneous tumour uptake inter-individually, but also intra-individually with divergent uptake between different tumour lesions [90, 92]. Moreover, high uptake on pretreatment 89Zr-atezolizumab (an antibody to PD-L1) PET showed stronger correlation with the clinical outcome than immunohistochemistry- or ribonucleic acid-sequencing-based biomarkers in patients subsequently undergoing PD-L1-targeted therapies.

Several trials in humans aimed at establishing novel immuno-PET ligands in a broad range of cancer entities such as 89Zr-avelumab PET in NSCLC (NCT03514719, PINNACLE trial) or 89Zr-durvalumab in head-and-neck squamous cell cancer (NCT03829007, PINCH trial). Also, dual imaging approaches with 18F-FDG PET are on the way, for example combining 18F-FDG PET and 18F-PD-L1 PET in oral cavity squamous cell cancer (NCT03843515, NeoNivo trial)

Beyond imaging PD-L1 using PET, several interesting biomarkers were introduced to molecular imaging in preclinical settings such as interferon-γ immuno-PET (89Zr-anti-IFN-γ) that allows imaging of activated lymphocytes inside tumour lesions [93]. Another interesting target is represented by the protease granzyme B (GZP). It is secreted by cytotoxic CD8+ during immune-induced, caspase-dependent apoptosis. Targeting imaging with 68Ga-NOTA-GZP allowed prediction of response to immunotherapy with high accuracy in preclinical models [94]. Beyond the scope of PET imaging, also promising molecular structures can be targeted using single-photon emission tomography ligands. Among them, a very encouraging perspective is offered by 99mTc-labeled interleukin-2 (99mTc-HYNIC-IL2), which demonstrated feasibility for visualisation and quantification of tumour infiltrating lymphocytes in a small set of melanoma patients undergoing immunotherapy, so providing a potential non-invasive tool for the differentiation between progression and pseudoprogression [95].

These promising efforts in both preclinical and clinical setting underline the further investigation of immuno-PET and the comprehensive translation into clinical imaging to further improve pretreatment patient selection, response assessment and clinical management. Moreover, artificial intelligence algorithms are increasingly used to evaluate treatment response by evaluating image-derived biomarkers [96, 97], which can also incorporate PET-derived information. Future trends also head towards integrated diagnostics’, i.e., combining multiparametric diagnostic data from imaging, pathology, molecular genetics, and liquid biopsies, with final aim of therapy guidance.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- CAR:

-

Chimeric antigen receptor

- CD:

-

Cluster of differentiation

- CR:

-

Complete response

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CTLA-4:

-

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4

- EMA:

-

European Medicines Agency

- EORTC:

-

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer

- FDG:

-

Fluorodeoxyglucose

- GZP:

-

Protease granzyme B

- HL:

-

Hodgkin lymphoma

- irAE:

-

Immune-related adverse events

- iRECIST:

-

Immune Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid tumours

- irRC:

-

Immune-related response criteria

- LYRIC:

-

Lymphoma response to immunomodulatory therapy criteria

- NSCLC:

-

Non-small cell lung cancer

- PD:

-

Progressive disease

- PD-1:

-

Programmed cell death protein 1

- PD-L1:

-

Programmed death-ligand 1

- PECRIT:

-

PET/CT criteria for early prediction of response to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy

- PERCIMT:

-

PET Response Evaluation Criteria for Immunotherapy

- PERCIST:

-

PET Response Criteria in Solid tumours

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- PR:

-

Partial response

- RECIL:

-

Response evaluation criteria in lymphoma

- RECIST:

-

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid tumours

- SD:

-

Stable disease

- SUL:

-

Standardised uptake value corrected for the lean body mass

- SUV:

-

Standardised uptake value

References

Sharpe AH, Pauken KE (2018) The diverse functions of the PD1 inhibitory pathway. Nat Rev Immunol 18:153–167. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri.2017.108

Wang Z, Cao YJ (2020) Adoptive cell therapy targeting neoantigens: a frontier for cancer research. Front Immunol 11:176. https://dx.doi.org/10.3389%2Ffimmu.2020.00176

Weber EW, Maus MV, Mackall CL (2020) The emerging landscape of immune cell therapies. Cell 181:46–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.001

Champiat S, Ferrara R, Massard C et al (2018) Hyperprogressive disease: recognizing a novel pattern to improve patient management. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 15:748–762. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-018-0111-2

Friedman CF, Proverbs-Singh TA, Postow MA (2016) Treatment of the immune-related adverse effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a review. JAMA Oncol 2:1346–1353. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.1051

Delbeke D, Schöder H, Martin WH, Wahl RL (2009) Hybrid imaging (SPECT/CT and PET/CT): improving therapeutic decisions. Semin Nucl Med 39:308–340. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2009.03.002

Eichenauer DA, Aleman BMP, André M et al (2018) Hodgkin lymphoma: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 29:iv19–iv29. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdy080

Buckner CD, Epstein RB, Rudolph RH, Clift RA, Storb R, Thomas ED (1970) Allogeneic marrow engraftment following whole body irradiation in a patient with leukemia. Blood 35:741–750

Wang W, Erbe AK, Hank JA, Morris ZS, Sondel PM (2015) NK cell-mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity in cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol 6:368. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2015.00368

Gul N, Babes L, Siegmund K et al (2014) Macrophages eliminate circulating tumour cells after monoclonal antibody therapy. J Clin Invest 124:812–823. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci66776

Montalvao F, Garcia Z, Celli S et al (2013) The mechanism of anti-CD20-mediated B cell depletion revealed by intravital imaging. J Clin Invest 123:5098–5103. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci70972

Rogers LM, Veeramani S, Weiner GJ (2014) Complement in monoclonal antibody therapy of cancer. Immunol Res 59:203–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12026-014-8542-z

Chambers CA, Kuhns MS, Egen JG, Allison JP (2001) CTLA-4-mediated inhibition in regulation of T cell responses: mechanisms and manipulation in tumour immunotherapy. Annu Rev Immunol 19:565–594. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.565

Franquiz MJ, Short NJ (2020) Blinatumomab for the treatment of adult B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: toward a new era of targeted immunotherapy. Biologics 14:23–34. https://doi.org/10.2147/btt.s202746

Loffler A, Gruen M, Wuchter C et al (2003) Efficient elimination of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia B cells by autologous T cells with a bispecific anti-CD19/anti-CD3 single-chain antibody construct. Leukemia 17:900–909. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.leu.2402890

Frigault MJ, Maus MV (2020) State of the art in CAR T cell therapy for CD19+ B cell malignancies. J Clin Invest 130:1586–1594. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci129208

Schuster SJ, Bishop MR, Tam CS et al (2019) Tisagenlecleucel in adult relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 380:45–56. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1804980

Neelapu SS, Locke FL, Bartlett NL et al (2017) Axicabtagene ciloleucel CAR T-cell therapy in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 377:2531–2544. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1707447

Abbasi A, Peeke S, Shah N et al (2020) Axicabtagene ciloleucel CD19 CAR-T cell therapy results in high rates of systemic and neurologic remissions in ten patients with refractory large B cell lymphoma including two with HIV and viral hepatitis. J Hematol Oncol 13:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-019-0838-y

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J et al (2009) New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 45:228–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026

Wolchok JD, Hoos A, O'Day S et al (2009) Guidelines for the evaluation of immune therapy activity in solid tumours: immune-related response criteria. Clin Cancer Res 15:7412–7420. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-09-1624

Bohnsack O, Hoos A, Ludajic K (2014) Adaptation of the immune related response criteria: irRECIST. Ann Oncol 25:iv369. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdu342.23

Seymour L, Bogaerts J, Perrone A et al (2017) iRECIST: guidelines for response criteria for use in trials testing immunotherapeutics. Lancet Oncol 18:e143–e152. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(17)30074-8

Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA et al (2000) New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumours. European Organization for Research and Treatment of cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst 92:205–216. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/92.3.205

Schwartz LH, Litière S, de Vries E et al (2016) RECIST 1.1-update and clarification: from the RECIST committee. Eur J Cancer 62:132–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2016.03.081

Chiou VL, Burotto M (2015) Pseudoprogression and immune-related response in solid tumours. J Clin Oncol 33:3541–3543. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2015.61.6870

Weber JS, D'Angelo SP, Minor D et al (2015) Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma who progressed after anti-CTLA-4 treatment (CheckMate 037): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 16:375–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(15)70076-8

Champiat S, Dercle L, Ammari S et al (2017) Hyperprogressive disease is a new pattern of progression in cancer patients treated by anti-PD-1/PD-L1. Clin Cancer Res 23:1920–1928. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-16-1741

Saâda-Bouzid E, Defaucheux C, Karabajakian A et al (2017) Hyperprogression during anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy in patients with recurrent and/or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol 28:1605–1611. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx178v

Frelaut M, Le Tourneau C, Borcoman E (2019) Hyperprogression under immunotherapy. Int J Mol Sci 20:2674. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20112674

Young H, Baum R, Cremerius U et al (1999) Measurement of clinical and subclinical tumour response using [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose and positron emission tomography: review and 1999 EORTC recommendations. Eur J Cancer 35:1773–1782. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00229-4

Sachpekidis C, Larribere L, Pan L, Haberkorn U, Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss A, Hassel JC (2015) Predictive value of early 18 F-FDG PET/CT studies for treatment response evaluation to ipilimumab in metastatic melanoma: preliminary results of an ongoing study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 42:386–396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-014-2944-y

Wahl RL, Jacene H, Kasamon Y, Lodge MA (2009) From RECIST to PERCIST: evolving considerations for PET response criteria in solid tumours. J Nucl Med 50:122S–150S. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.108.057307

Cho SY, Lipson EJ, Im H-J et al (2017) Prediction of response to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy using early-time-point 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging in patients with advanced melanoma. J Nucl Med 58:1421–1428. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.116.188839

Anwar H, Sachpekidis C, Winkler J et al (2018) Absolute number of new lesions on 18 F-FDG PET/CT is more predictive of clinical response than SUV changes in metastatic melanoma patients receiving ipilimumab. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 45:376–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-017-3870-6

Sachpekidis C, Anwar H, Winkler J et al (2018) The role of interim 18 F-FDG PET/CT in prediction of response to ipilimumab treatment in metastatic melanoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 45:1289–1296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-018-3972-9

Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B et al (1999) Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. J Clin Oncol 17:1244. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.1999.17.4.1244

Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME et al (2007) Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 25:579–586. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2006.09.2403

Meignan M, Gallamini A, Meignan M, Gallamini A, Haioun C (2009) Report on the first international workshop on interim-PET scan in lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma 50:1257–1260. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428190903040048

Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF et al (2014) Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol 32:3059–3068. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2013.54.8800

Cheson BD, Ansell S, Schwartz L et al (2016) Refinement of the Lugano classification lymphoma response criteria in the era of immunomodulatory therapy. Blood 128:2489–2496. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2016-05-718528

Younes A, Hilden P, Coiffier B et al (2017) International working group consensus response evaluation criteria in lymphoma (RECIL 2017). Ann Oncol 28:1436–1447. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx097

Kong BY, Menzies AM, Saunders CA et al (2016) Residual FDG-PET metabolic activity in metastatic melanoma patients with prolonged response to anti-PD-1 therapy. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 29:572–577. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcmr.12503

Kaira K, Higuchi T, Naruse I et al (2018) Metabolic activity by 18 F–FDG-PET/CT is predictive of early response after nivolumab in previously treated NSCLC. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 45:56–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-017-3806-1

Spigel DR, Chaft JE, Gettinger S et al (2018) FIR: efficacy, safety, and biomarker analysis of a phase II open-label study of atezolizumab in PD-L1–selected patients with NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol 13:1733–1742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2018.05.004

Humbert O, Cadour N, Paquet M et al (2020) 18FDG PET/CT in the early assessment of non-small cell lung cancer response to immunotherapy: frequency and clinical significance of atypical evolutive patterns. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 47:1158–1167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-019-04573-4

Ansell SM, Lesokhin AM, Borrello I et al (2015) PD-1 blockade with nivolumab in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med 372:311–319. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1411087

Armand P, Shipp MA, Ribrag V et al (2016) Programmed death-1 blockade with pembrolizumab in patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma after brentuximab vedotin failure. J Clin Oncol 34:3733–3739. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2016.67.3467

Chen R, Zinzani PL, Fanale MA et al (2017) Phase II study of the efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab for relapsed/refractory classic Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 35:2125–2132. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2016.72.1316

Armand P, Engert A, Younes A et al (2018) Nivolumab for relapsed/refractory classic Hodgkin lymphoma after failure of autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation: extended follow-up of the multicohort single-arm phase II CheckMate 205 trial. J Clin Oncol 36:1428–1439. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2017.76.0793

Moskowitz CH, Zinzani PL, Fanale MA et al (2016) Pembrolizumab in relapsed/refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma: primary end point analysis of the phase 2 Keynote-087 study. Blood 128:1107–1107

Maruyama D, Hatake K, Kinoshita T et al (2017) Multicenter phase II study of nivolumab in Japanese patients with relapsed or refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer Sci 108:1007–1012. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.13230

Chan TSY, Luk T-H, Lau JSM, Khong P-L, Kwong Y-L (2017) Low-dose pembrolizumab for relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma: high efficacy with minimal toxicity. Ann Hematol 96:647–651. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-017-2931-z

Rossi C, Gilhodes J, Maerevoet M et al (2018) Efficacy of chemotherapy or chemo-anti-PD-1 combination after failed anti-PD-1 therapy for relapsed and refractory hodgkin lymphoma: a series from lysa centers. Am J Hematol 93:1042–1049. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.25154

Dercle L, Seban R-D, Lazarovici J et al (2018) 18F-FDG PET and CT scans detect new imaging patterns of response and progression in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma treated by anti–programmed death 1 immune checkpoint inhibitor. J Nucl Med 59:15–24. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.117.193011

Dercle L, Ammari S, Seban R-D et al (2018) Kinetics and nadir of responses to immune checkpoint blockade by anti-PD1 in patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Eur J Cancer 91:136–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2017.12.015

Mokrane F-Z, Chen A, Schwartz LH et al (2020) Performance of CT compared with 18F-FDG PET in predicting the efficacy of nivolumab in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Radiology 295:651-661. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020192056

Chen A, Mokrane F-Z, Schwartz LH et al (2020) Early 18F-FDG PET/CT response predicts survival in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma treated with Nivolumab. J Nucl Med 61:649–654. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.119.232827

Castello A, Grizzi F, Qehajaj D, Rahal D, Lutman F, Lopci E (2019) 18F-FDG PET/CT for response assessment in Hodgkin lymphoma undergoing immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors. Leuk Lymphoma 60:367–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428194.2018.1488254

Shah NN, Nagle SJ, Torigian DA et al (2018) Early positron emission tomography/computed tomography as a predictor of response after CTL019 chimeric antigen receptor –T-cell therapy in B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Cytotherapy 20:1415–1418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcyt.2018.10.003

Wang J, Hu Y, Yang S et al (2019) Role of fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in predicting the adverse effects of chimeric antigen receptor t cell therapy in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 25:1092–1098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2019.02.008

Basler L, Gabryś HS, Hogan SA et al (2020) Radiomics, tumour volume and blood biomarkers for early prediction of pseudoprogression in metastatic melanoma patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibition. Clin Cancer Res. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-0020

Seith F, Forschner A, Weide B et al (2020) Is there a link between very early changes of primary and secondary lymphoid organs in (18)F-FDG-PET/MRI and treatment response to checkpoint inhibitor therapy? J Immunother Cancer 8:e000656. https://dx.doi.org/10.1136%2Fjitc-2020-000656

Cousin S, Italiano A (2016) Molecular pathways: immune checkpoint antibodies and their toxicities. Clin Cancer Res 22:4550–4555

Nishijima TF, Shachar SS, Nyrop KA, Muss HB (2017) Safety and tolerability of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors compared with chemotherapy in patients with advanced cancer: a meta-analysis. Oncologist 22:470. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0419

Khoja L, Day D, Wei-Wu Chen T, Siu L, Hansen A (2017) Tumour-and class-specific patterns of immune-related adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review. Ann Oncol 28:2377–2385. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx286

Foppen MHG, Rozeman EA, van Wilpe S et al (2018) Immune checkpoint inhibition-related colitis: symptoms, endoscopic features, histology and response to management. ESMO open 3:e000278. https://doi.org/10.1136/esmoopen-2017-000278

Fujii T, Colen RR, Bilen MA et al (2018) Incidence of immune-related adverse events and its association with treatment outcomes: the MD Anderson Cancer Center experience. Investig New Drugs 36:638–646. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10637-017-0534-0

Rossi S, Toschi L, Castello A, Grizzi F, Mansi L, Lopci E (2017) Clinical characteristics of patient selection and imaging predictors of outcome in solid tumours treated with checkpoint-inhibitors. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 44:2310–2325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-017-3802-5

Tsai KK, Pampaloni MH, Hope C et al (2016) Increased FDG avidity in lymphoid tissue associated with response to combined immune checkpoint blockade. J Immunother Cancer 4:58. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40425-016-0162-9

Wachsmann JW, Ganti R, Peng F (2017) Immune-mediated disease in ipilimumab immunotherapy of melanoma with FDG PET-CT. Acad Radiol 24:111–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acra.2016.08.005

Nobashi T, Baratto L, Reddy SA et al (2019) Predicting response to immunotherapy by evaluating tumours, lymphoid cell-rich organs, and immune-related adverse events using FDG-PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med 44:e272–e279. https://doi.org/10.1097/rlu.0000000000002453

Haratani K, Hayashi H, Chiba Y et al (2018) Association of immune-related adverse events with nivolumab efficacy in non–small-cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol 4:374–378. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.2925

Aide N, Hicks RJ, Le Tourneau C, Lheureux S, Fanti S, Lopci E (2019) FDG PET/CT for assessing tumour response to immunotherapy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 46:238–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-018-4171-4

Nishino M, Hatabu H, Hodi FS (2019) Imaging of cancer immunotherapy: current approaches and future directions. Radiology 290:9–22. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2018181349

Brudno JN, Kochenderfer JN (2016) Toxicities of chimeric antigen receptor T cells: recognition and management. Blood 127:3321–3330. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2016-04-703751

Neelapu SS, Tummala S, Kebriaei P et al (2018) Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy — assessment and management of toxicities. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 15:47–62. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.148

Hu Y, Wang J, Pu C et al (2018) Delayed terminal ileal perforation in a relapsed/refractory B-cell lymphoma patient with rapid remission following chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. Cancer Res Treat 50:1462–1466. https://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2017.473

Wang Y, Zhang W-y, Han Q-w et al (2014) Effective response and delayed toxicities of refractory advanced diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated by CD20-directed chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells. Clin Immunol 155:160-175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2014.10.002

Cohen AD, Garfall AL, Stadtmauer EA et al (2019) B cell maturation antigen-specific CAR T cells are clinically active in multiple myeloma. J Clin Invest 129:2210–2221. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci126397

Raje N, Berdeja J, Lin Y et al (2019) Anti-BCMA CAR T-cell therapy bb2121 in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 380:1726–1737. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1817226

Fry TJ, Shah NN, Orentas RJ et al (2018) CD22-targeted CAR T cells induce remission in B-ALL that is naive or resistant to CD19-targeted CAR immunotherapy. Nat Med 24:20–28. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.4441

Titov A, Valiullina A, Zmievskaya E et al (2020) Advancing CAR T-cell therapy for solid tumours: lessons learned from lymphoma treatment. Cancers (Basel) 12:125. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12010125

Bachmann M (2019) The UniCAR system: a modular CAR T cell approach to improve the safety of CAR T cells. Immunol Lett 211:13–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imlet.2019.05.003

Lee YG, Marks I, Srinivasarao M et al (2019) Use of a single CAR T cell and several bispecific adapters facilitates eradication of multiple antigenically different solid tumours. Cancer Res 79:387–396. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-18-1834

Minutolo NG, Hollander EE, Powell DJ Jr (2019) The emergence of universal immune receptor T cell therapy for cancer. Front Oncol 9:176. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2019.00176

Liu E, Marin D, Banerjee P et al (2020) Use of CAR-transduced natural killer cells in CD19-positive lymphoid tumours. N Engl J Med 382:545–553. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1910607

Natarajan A, Mayer AT, Reeves RE, Nagamine CM, Gambhir SS (2017) Development of novel immunoPET tracers to image human PD-1 checkpoint expression on tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in a humanized mouse model. Mol Imaging Biol 19:903–914. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11307-017-1060-3

Natarajan A, Mayer AT, Xu L, Reeves RE, Gano J, Gambhir SS (2015) Novel radiotracer for immunoPET imaging of PD-1 checkpoint expression on tumour infiltrating lymphocytes. Bioconjug Chem 26:2062–2069. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00318

Verhoeff SR, van den Heuvel MM, van Herpen CM, Piet B, Aarntzen EH, Heskamp S (2020) Programmed cell Death-1/Ligand-1 PET imaging: a novel tool to optimize immunotherapy? PET Clin 15:35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpet.2019.08.008

Bensch F, van der Veen EL, Lub-de Hooge MN et al (2018) 89Zr-atezolizumab imaging as a non-invasive approach to assess clinical response to PD-L1 blockade in cancer. Nat Med 24:1852–1858. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0255-8

Niemeijer A, Leung D, Huisman M et al (2018) Whole body PD-1 and PD-L1 positron emission tomography in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat Commun 9:4664. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07131-y

Gibson HM, McKnight BN, Malysa A et al (2018) IFNγ PET imaging as a predictive tool for monitoring response to tumour immunotherapy. Cancer Res 78:5706–5717. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-18-0253

Larimer BM, Wehrenberg-Klee E, Dubois F et al (2017) Granzyme B PET imaging as a predictive biomarker of immunotherapy response. Cancer Res 77:2318–2327. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-16-3346

Markovic SN, Galli F, Suman VJ et al (2018) Non-invasive visualization of tumour infiltrating lymphocytes in patients with metastatic melanoma undergoing immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: a pilot study. Oncotarget 9:30268-30278. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.25666

Ting DS, Liu Y, Burlina P, Xu X, Bressler NM, Wong TY (2018) AI for medical imaging goes deep. Nat Med 24:539–540. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0029-3

Wu M, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Wu M, Ye Z (2019) Imaging-based biomarkers for predicting and evaluating cancer immunotherapy response. Radiol Imag Cancer 1:e190031. https://doi.org/10.1148/rycan.2019190031

Authorsʼ contributions

M.U.: conception, manuscript draft, literature review, increased intellectual content, revision. M.R.: manuscript draft, literature review, increased intellectual content, revision. M.P.F: manuscript draft, literature review, increased intellectual content, revision. L.M.M.: manuscript draft, literature review, increased intellectual content, revision. M.W.: literature review, increased intellectual content, revision. J.R.: literature review, increased intellectual content, revision. M.B.: literature review, increased intellectual content, revision. M.S.: literature review, increased intellectual content, revision. M.B.B.: literature review, increased intellectual content, revision. J.R.: literature review, increased intellectual content, revision. W.G.K.: conception, literature review, increased intellectual content, revision. C. C. C.: conception, literature review, increased intellectual content, revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study has not received any funding. Open Access funding enabled and organised by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No patient-related data was used; therefore, no additional statement from respective ethic committees was mandatory.

Consent for publication

Not mandatory as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no relationships or interests that could have direct or potential influence or impart bias on the work.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Unterrainer, M., Ruzicka, M., Fabritius, M.P. et al. PET/CT imaging for tumour response assessment to immunotherapy: current status and future directions. Eur Radiol Exp 4, 63 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41747-020-00190-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41747-020-00190-1