Abstract

Background

Dysregulation of cellular processes related to protein folding and trafficking leads to the accumulation of misfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), triggering ER stress. Cells cope with ER stress by activating the unfolded protein response (UPR), a signaling pathway that has been implicated in a variety of diseases, including cancer. However, the role of the UPR in cancer initiation and progression is still unclear.

Methods

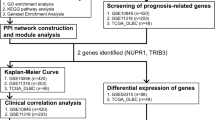

Here we used bulk and single cell RNA sequencing data to investigate ER stress-related gene expression in glioblastoma, as well as the impact key UPR genes have on patient survival.

Results

ER stress-related genes are highly expressed in both cancer cells and tumor-associated macrophages, with evidence of high intra- and inter-tumor heterogeneity. High expression of the UPR-related genes HSPA5, P4HB, and PDIA4 was identified as risk factors while high MAPK8 (JNK1) expression was identified as a protective factor in glioblastoma patients, indicating UPR genes have prognostic potential in this cancer type. Finally, expression of XBP1 and MAPK8, two key downstream targets of the ER sentinel IRE1α, correlates with the presence of immune cell types associated with immunosuppression and a worse patient outcome. This suggests that the expression of these genes is associated with an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment and uncover a potential link between stress response pathways, tumor microenvironment and glioblastoma patient survival.

Conclusions

We performed a comprehensive transcriptional characterization of the unfolded protein response in glioblastoma patients and identified UPR-related genes associated with glioblastoma patient survival, providing potential prognostic and predictive biomarkers as well as promising targets for developing new therapeutic interventions in glioblastoma treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is the major site for protein folding and quality control for approximately one-third of all cellular proteins [1]. An imbalance between the protein load entering the ER and the ER’s protein folding capacity results in ER stress and subsequent activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR). The UPR is initiated through the activation of three ER transmembrane sensors within the ER: PERK (protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase), IRE1α (Inositol-requiring protein 1 alpha), and ATF6 (activating transcription factor 6). The UPR’s primary objective is to restore protein homeostasis by increasing ER folding capacity, attenuating general translation, and facilitating the removal of misfolded proteins through the ER-associated degradation (ERAD) system [2, 3]. However, chronic or irreversible ER stress leads to cell death by apoptosis [4].

Glioblastoma is an aggressive and often fatal brain tumor with a median survival of 15 to 18 months [5]. The standard treatment is surgical resection, followed by radiotherapy and temozolomide chemotherapy [6]. Several studies have proposed a role for the UPR in mediating chemoresistance across different cancer types, including glioma [7,8,9,10,11,12]. Pharmacological modulation of the UPR has shown potential in cell culture models [10,11,12,13,14]. Consequently, targeting specific UPR components or inducing acute ER stress may hold therapeutic potential for managing glioblastoma. Additionally, the available molecular biomarkers in glioblastoma remain limited, primarily comprising MGMT promoter methylation, TERT promoter mutations, and EGFR overexpression [15]. Therefore, the identification of novel biomarkers can significantly improve patient management.

Glioblastoma cells, xenograft tumors, and patient samples show elevated transcript and protein levels of chaperones [7, 9, 16, 17], especially HSPA5, a gene whose elevated expression has been correlated with poor prognosis in glioblastoma patients [9]. In addition, previous studies have identified a role for the IRE1α branch in angiogenesis [18], tumor cell invasion [19], and immune infiltration [20] in glioblastoma, as well as associated the IRE1α-XBP1 pathway with reduced patient survival [20, 21]. In a recent report, the spliced form of XBP1 was overexpressed in glioblastoma samples, and the inhibition of its splicing potentiated the effect of temozolomide in vitro [22]. Yet, a comprehensive characterization of UPR-related gene expression in glioblastoma patient samples is still lacking [13]. Moreover, it is crucial to recognize that the UPR exerts a substantial influence on non-malignant cell types and interactions within the tumor microenvironment [23, 24]. Therefore, to gain a comprehensive understanding of how the UPR influences glioblastoma, we must consider the entire tumor ecosystem.

Here, we harnessed both bulk and single cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data to delve into the expression patterns of ER stress-related genes in glioblastoma, as well as the impact key UPR genes have on patient survival. Our investigation unveiled a substantial upregulation of the UPR in glioblastoma patient samples and pinpointed factors that could either increase or decrease the risk associated with the disease. Importantly, our analysis of both single-cell and bulk data highlighted that the gene expression of IRE1α downstream targets, specifically XBP1 and JNK1, yields contrasting effects on the composition of the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME). This finding suggests a potential mechanism by which these UPR pathways influence the survival of glioblastoma patients.

Methods

Data origin

scRNA-seq data processed with 10X Genomics were obtained from Neftel et al. 2019 [25]. We excluded the 539 cells from pediatric patients and therefore analyzed 30,401 genes across 15,662 glioblastoma cells from 9 tumor samples (Table S1). Among these, two samples (105 and 105A) originated from distinct locations of the same tumor. In addition, bulk microarray and RNA-seq expression data of glioblastoma patients with clinical information were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Firehose Legacy dataset and TCGA PanCancer Atlas dataset (Table S2), respectively, through the cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics [26, 27]. Expression data from low-grade glioma patients was also from PanCancer Atlas dataset. Microarray expression data of normal brain tissue and glioma patients with different tumor grades were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) Platform GPL570 (Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array) through the Gene Expression database of Normal and Tumor tissues 2 (Gent2) [28]. The expression data of normal brain samples was obtained from 33 different GEO series, and the expression data of the glioblastoma tissues was from 11 GEO series (Table S3).

scRNA-seq processing and analysis

Single cell data analysis was performed in R software using the Seurat package (version 4.0) [29]. Normalization and variance stabilization of molecular count data was carried out by SCTransform. Following a Seurat workflow, we assigned each cell a cell-cycle score, based on its expression of G2/M and S phase markers [30], and regressed out the difference between these two scores. Subsequently, data dimensionality reduction was performed using a principal component analysis (PCA), and the first 25 principal components were used for clustering through a graph-based approach, by which we constructed a k-nearest neighbor graph based on distances in PCA space and then applied the Louvain algorithm. The resolution parameter was set to 1. Clustering results were visualized using two-dimensional Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP). Clusters were identified based on the expression of reported markers [25].

ER stress gene signature

Transcriptome profiles of glioma cells treated for 2 and 6 h with the classical ER stress inducers, thapsigargin and tunicamycin, were obtained from Reich et al. 2020 [31] via GEO (GSE129757). The most significantly upregulated genes (all p < 0.005 and log2FC > 1.60) across these conditions were selected and only those upregulated in at least two experimental conditions were chosen for the signature. To validate the meta-signature, we examined the differential expression of the signature genes in three GEO series (GSE24497, GSE21979, and GSE107859). These series involved the treatment of various brain tumor cell lines with either tunicamycin or thapsigargin. Additionally, we analyzed one GEO dataset (GSE7806) where glioblastoma cells were treated with a non-classical inducer, a small methylpyrazole-based molecule named erstressin [32] (Fig. S1, Table S4). This 37-gene signature was used for further analyses of the single cell expression data (Table S5).

Differential expression analysis

For both differential expression and survival analyses, we examined the behavior of an additional set of 25 UPR genes curated from the literature and that are well-known components of the different UPR branches [1, 4] (Table S6). We compared expression levels in normal brain tissue samples and glioblastoma tumor samples from GEO, as well as between low-grade glioma and glioblastoma samples from TCGA. Normality was rejected using the Shapiro–Wilk normality test and therefore the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test was chosen. To access differential expression across glioma grades, Kruskal Wallis test was carried out comparing data among grade II, III and IV glioma samples, and Dunn’s test was performed for multiple comparisons.

Kaplan–Meier analysis

Kaplan–Meier analyses were performed individually for each of the 25 UPR genes, using the median to separate patients with low and high expression. In addition, Kaplan–Meier analysis using two genes (XBP1 and MAPK8) was performed dividing patients into 4 groups according to Pereira et al. 2018 [33].

Cox regression analysis

Cox regression models were performed to calculate the hazard ratio using mRNA expression z-scores and overall survival data. The models were adjusted for the impact of the clinical variable Sex or adjusted for the impact of both Sex and all other 24 genes. Other pertinent clinical variables either lacked sufficient data or did not meet the proportional hazard assumption, as verified through diagnostic analysis utilizing weighted Schoenfeld residuals. Cox models were carried out using the R survival package (version 3.2–13).

Immune cell meta-signatures

Meta-signatures representing different cells of the immune system were previously described [33]. The meta-signatures were obtained by the average expression z-scores of the genes corresponding to each cell type.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism 8.0.2 Software. Two-sided p-values < 0.05 were statistically significant.

Results

Characterization of UPR gene expression in the TME

Single cell transcriptomic profiles for 30,401 genes across 15,662 cells from 9 tumor samples produced clear clusters of tumor cells, macrophages, oligodendrocytes, and T cells based on the expression of reported cell-type specific markers [25] (Fig. 1A and B). Within each cluster, gene expression pattern varied noticeably in cells from different patients, especially tumor cells and macrophages, as already reported [25] (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, the two samples derived from distinct locations of the same tumor, 105 and 105A, were clustered separately, indicating significant variations in gene expression patterns based on the cells’ location within the tumor. To examine the variability in ER stress levels, we created a gene signature associated with ER stress. This signature was established by identifying genes that are upregulated in brain tumor cells treated with classical ER stress-inducing agents, namely thapsigargin (a specific sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase inhibitor) and tunicamycin (a N-glycosylation inhibitor). These agents promptly activate key factors of the UPR and their downstream targets [31] (Table S5). The ER stress gene signature was expressed in all four clusters,

Characterization of UPR gene expression in the TME. A Identification via scRNAseq of cell populations from 9 glioblastoma samples. UMAP plot of all single cells. Cells are colored based on high expression of sets of marker genes for tumor cells (red), macrophages (green), oligodendrocytes (blue), and T cells (purple). B Expression of marker genes used for the identification of cluster cell types, according to Neftel et al. 2019 [25]. C UMAP plot of all single cells, colored by sample. D Feature plot depicting expression of an ER stress gene signature. E Ridge plot of signature expression. Average signature expression is shown for each cell type. Feature F and Ridge G plots depicting genes involved in UPR

showing high expression in both tumor cells and macrophages (Fig. 1D and E, Table S7). When looking at four representative individual genes involved in UPR pathways and upregulated by ER stress, we observed a similar pattern: expression is present in all clusters but mainly in macrophages and tumor cells (Fig. 1F and G). Additionally, expression of both signature and individual genes varied considerably among patients—while some tumors showed very low ER stress marker expression, others highly expressed the signature (Fig. 1C and D, Fig. S2). Lastly, there was also heterogeneity within each patient—sub-groups of cells within the same tumor showed specific expression patterns (Fig. 1C and D). Interestingly, patients with high expression of the signature in tumor cells also showed high expression in macrophages cells (Fig. S2A and B). Recognizing the significance of assessing gene expression separately in M1 and M2 macrophage subpopulations, we made a concerted effort to cluster the macrophage subset in the scRNAseq dataset. In our endeavor to classify macrophages into M1 and M2 subtypes for the purpose of evaluating ER stress expression in these distinct populations, variations observed across samples obscured the differences among subtypes. This challenge impeded the accurate segregation between M1 and M2 macrophages.

UPR is highly upregulated in glioblastoma patient samples

To comprehensively study the UPR landscape in glioblastoma patients, we evaluated the differential expression of major UPR genes in glioblastoma patient samples. We analyzed a set of 25 genes [1, 4] (Table S6), comparing microarray expression data of 844 normal brain tissue samples and 408 glioblastoma tumor samples obtained from GEO Platform GPL570 (Table S3). Almost all genes analyzed showed elevated expression in tumor samples relative to normal brain tissue (Fig. 2A, Fig. S3A). These upregulated genes include the three UPR transducers EIF2AK3 (PERK), ATF6, and ERN1 (IRE1α); the transcription factors XBP1, ATF4, and DDIT3 (CHOP); and their targets, such as the ER chaperones HSPA5 (GRP78) and HSP90B1 (GRP74), and other genes involved in the folding machinery and the ERAD pathway. The only two downregulated genes in tumor samples were MAPK8, which encodes the JNK1 protein, implicated in IRE1α-mediated apoptosis [34, 35], and SEL1L, whose product is a member of the ERAD system that associates with HRD1 (SYVN1) and OS9 to translocate misfolded proteins to the cytosol [36]. Likewise, most UPR genes within the subset studied were overexpressed in glioblastoma compared to low-grade glioma and their expression levels correlated with tumor grade (Fig. 2B, Fig. S3B and C). SEL1L and MAPK8 were also downregulated in glioblastoma when compared to low-grade glioma, and MAPK8 expression was negatively correlated with tumor grade.

UPR genes differential expression and impact on patient survival. A Radar charts showing the change in expression (%) of each gene between normal brain tissue (n = 844) and glioblastoma samples (n = 408). Mann–Whitney U test was carried out comparing the microarray expression data from GEO. B Radar charts showing the change in expression (%) between low-grade glioma (n = 514) and glioblastoma samples (n = 155). Mann–Whitney U test was carried out comparing the RNA-seq expression data from TCGA cohort. The points in the chart vertices indicate a significant change in expression and the red line indicates zero change in expression. C Kaplan–Meier plots of the genes that showed a significant impact on survival using microarray data (n = 401) from the TCGA cohort. Log-rank p values are indicated. Cox proportional hazard ratio of genes with significant impact adjusted only to the clinical variable Sex (in red) and adjusted to Sex and all other genes (in blue) using D Microarray data (n = 401) and E RNA-seq data (n = 155) from TCGA

Identification of novel risk and protective UPR factors in glioblastoma

Next, we evaluated the impact of individual UPR genes on patient survival. Kaplan–Meier analysis was carried out for each of the 25 UPR genes included in the UPR subset, of which nine exhibited prognostic significance in patients with glioblastoma using microarray data from the TCGA cohort (Fig. 2C, Fig. S4A). To further determine the prognostic implication of the UPR genes, multivariate Cox proportional hazard ratio analysis was performed for the same 25 genes adjusted only to the clinical variable Sex or adjusted to Sex and all other genes, using microarray and RNA-seq data from TCGA cohorts (Fig. 2D and E, Fig. S4B and C, Table S8). The Kaplan–Meier curves showed that high expression of six genes was associated significantly with shorter survival, while the high expression of three genes was associated with a better prognosis. Similarly, Cox survival analysis identified seven genes as risk factors and four as protective factors. Considering genes that were significant in Kaplan–Meier as well as in Cox analyses from both microarray and RNA seq datasets, we identified three risk factors (HSPA5, P4HB, and PDIA4) and one protective factor (MAPK8).

Opposing roles of IRE1α downstream pathways in patient prognosis and presence of immune cells in TME

Given the opposing roles of the IRE1α branch, which on one side leads to the induction of apoptosis via JNK1 and on the other triggers adaptive responses through XBP1 [34, 35, 37], we next focused on the role of XBP1 and MAPK8 in glioblastoma. We performed a Kaplan–Meier analysis to investigate the impact of XBP1 and MAPK8 gene interaction on survival. Patients were divided into 4 equal groups, as shown in Fig. S5A [33]. Patients with high MAPK8 and low XBP1 expression had significantly better prognoses than patients with low MAPK8 and high XBP1 expression (Fig. 3A). IRE1α downstream pathways are associated with immune infiltration and tumor-stroma interaction mainly through the regulation of cytokines in tumor and immune cells [23, 38]. JNK1 can regulate the inflammatory responses in cancer cells through NF-κB pathway, and IRE1α-XBP1 signaling in glioblastoma cells can enhance expression of cytokines that participate in the chemoattraction of macrophages to the TME [20, 23]. We measured the expression of immune cell markers and meta-signatures in the Low–High and High-Low patient groups, as well as in the XBP1 and MAPK8 individual low and high expression groups. High XBP1 and low MAPK8 was associated with an elevated expression of immune markers and immune cell meta-signatures (Fig. 3B and C, Fig. S5B and C). The highly overexpressed immune meta-signatures (p < 0.05 and FoldChange > 1.5) in patients with high XBP1 and low MAPK8 expression were all of cell types that were previously associated with immunosuppression and a worst prognosis in glioblastoma patients (Treg, Th1, MDSC, macrophages, NK, and NK T) [33]. Overall, individual marker expressions were consistent with the results obtained from meta-signature analysis, except for T cells. Specifically, while CD4 expression was upregulated and the global T cell marker CD3G was downregulated, the T CD4 signature remained unchanged, and there was a modest increase in T CD8 expression. Furthermore, both M1 and M2 macrophage markers exhibited heightened expression levels, with the M2 marker CD163 notably demonstrating the highest fold change. Additionally, the specific microglial markers displayed patterns similar to those of macrophages. We then performed further analyses with scRNA-seq data to investigate if these findings were not due to the intrinsic expression of these genes in immune cells. XBP1 and MAPK8 were expressed across all clusters, mainly in the macrophage population (Fig. 3D, Fig. S5D). In fact, the ratio of XBP1 and MAPK8 average expression only in tumor cells positively correlated with the percentage of immune cells in the tumor for each sample (Fig. 3E, Table S7). XBP1 and MAPK8 expression in tumor cells alone correlated with the percent of immune cells in the tumor (XBP1: r = 0.59; MAPK8: r = -0.26), but their ratio showed a much stronger correlation (r = 0.79) (Fig. S5E). Thus, XBP1 and MAPK8 expression ratio may suggest an immunosuppressive TME.

IRE1 downstream pathways have opposing roles in prognosis and presence of immune cells in TME. A Kaplan Meier survival analysis based on the expression of XBP1 and MAPK8 was performed dividing patients into 4 groups. Only High-Low compared to Low–High was significantly different (p = 0.03; High-High vs. Low–High: p = 0.17; Low-Low vs. Low–High: p = 0.25; High-High vs. High-Low: p = 0.30; Low-Low vs. High-Low: p = 0.46; High-High vs. Low-Low: p = 0.92). Expression of immune cell markers (B) and immune cell meta-signatures (C) in Low–High and High-Low groups. Mann–Whitney U test was carried out comparing microarray expression data from the TCGA cohort. D Feature plot depicting XBP1/MAPK8 expression ratio in single cells of the 9 glioblastoma samples from scRNA-seq data. E Comparison between the ratio of XBP1 and MAPK8 average expression only in tumor cells with the percent of immune cells in each sample. Each dot represents one tumor sample from scRNA-seq data. Samples’ IDs are indicated. Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) and p-value (p) are shown

Discussion

In this investigation, we have substantiated the upregulation of UPR (unfolded protein response) stress pathways within glioblastoma tumors. We have also pinpointed UPR-related genes whose expression levels exhibit significant associations with patient prognosis. Furthermore, we have unraveled a compelling correlation between the expression levels of two pivotal UPR genes and the enrichment of immune cells within the TME (Fig. 4).

Schematic representation of the main results in this work. The arrows indicate genes identified as upregulated (red) or downregulated (blue) in glioblastoma compared to normal brain samples. The shapes colored in red indicate genes identified as risk factors in the survival analyses, while protective factors are indicated in blue. The size of the arrows represents the change in expression, and the size of the shapes indicates how many survival analyses identified that gene as significant. On the left, a representative tumor with the four cell types identified from the scRNA-seq data and the potential association between XBP1 and MAPK8 expression with the presence of immune cells is shown. ATF6c: cleaved ATF6; XBP1s: spliced XBP1. Adapted from “UPR Signaling (ATF6, PERK, IRE1)”, by BioRender.com (2022). Retrieved from https://app.biorender002Ecom/biorender-templates

Our analysis has unveiled an increase in the expression of ER stress-related genes in glioblastoma when compared to normal tissue and low-grade gliomas. This upregulation stems not only from tumor cells but also from non-tumor cells within the TME, primarily macrophages. Importantly, we observed pronounced intra- and inter-tumor heterogeneity in the expression of ER stress signatures and markers. This heightened expression of ER stress-related genes encompassed nearly all the UPR-related genes we examined, with one noteworthy exception being MAPK8.

Crucially, we have identified certain UPR-related genes, including HSPA5, P4HB, and PDIA4, as robust risk factors, demonstrating their significant prognostic relevance across all three survival analyses conducted. Additionally, OS9 and HSP90B1 emerged as prognostically relevant in two out of the three analyses. These findings align with previous research, which has highlighted the overexpression of HSPA5 and the PDI (protein disulfide isomerase) family in glioblastoma models [9, 10]. This consistency reinforces the notion that UPR's cytoprotective branches play a pivotal role in facilitating the rapid growth of tumors and their ability to adapt to the challenging conditions of the microenvironment.

While several ERAD genes exhibited upregulation in glioblastoma tumors and were designated as risk factors, a notable exception was SEL1L. In contrast to previous findings that indicated an escalation in SEL1L protein expression with increasing malignancy in glioma cells and tissues [39, 40], we observed a downregulation of SEL1L in glioblastoma tissue when compared to normal brain and low-grade glioma samples. Notably, SEL1L presents multiple alternative transcripts encoding putative protein isoforms, suggesting that its role may oscillate between oncogenic and tumor-suppressive, contingent upon the cellular context and the prevailing isoform predominance [40].

Another gene exhibiting downregulation in glioblastoma, MAPK8, emerged as a protective factor in all three survival analyses conducted. Previous studies have alluded to the prognostic significance of the MAPK8 gene, postulating that this relevance is rooted in its involvement in programmed cell death [41, 42]. ERN1 (IRE1α), which serves as the activator of MAPK8 within the context of UPR signaling, was also identified as a protective factor in two of the analyses. This finding diverges from a prior report that associated high ERN1 expression with poor prognosis in glioblastoma patients [20]. Notably, in our Cox regression analysis, ERN1 did not emerge as a prognostic factor when adjusted for MAPK8 as a covariate (data not shown), implying that its prognostic relevance may be contingent upon the protective role of MAPK8.

Regarding the PERK/eIF2α/ATF4 branch, our analysis revealed that all the scrutinized genes exhibited upregulation in glioblastoma compared to normal tissue. This finding agrees with previous reports that showed elevated protein and transcript levels of both ATF4 and its target CHOP (DDIT3) of in xenograft tumors [9]. Additionally, these findings align with the observed positive correlation between PERK activation and tumor grade in glioma [9, 43].

Although none of the analyzed genes of this branch had a significant impact on prognosis across all three survival analyses, EIF2A and TRIB3, the latter being an apoptosis-related gene activated by CHOP [44], emerged as protective factors based on Kaplan–Meier curve and Cox analysis, respectively. In contrast, ATF3 and ATF5, which are induced by the eIF2α/ATF4 pathway, were identified as risk factors in one and two of the survival analyses, respectively. These findings are consistent with previous reports in other cancer types [45, 46]. These results underscore the complexity of this pathway, that leads to an intricate balance between cytoprotective and cytotoxic outcomes.

Intrigued by the contrasting functions of the IRE1α branch, which can either induce apoptosis via JNK1 or promote survival through the XBP1-dependent activation of adaptive responses, we conducted a survival analysis involving these two genes. In line with their antagonistic roles within the UPR signaling pathway, we observed that patients with elevated XBP1 expression and reduced MAPK8 expression experienced shorter survival compared to patients exhibiting low XBP1 and high MAPK8 expression. However, it is important to note that our standard transcriptomic methods did not provide access to crucial details such as XBP1 mRNA splicing or JNK1 (MAPK8) phosphorylation levels. Additionally, multiple pathways distinct from the UPR can converge on the phosphorylation of JNK1, making it an indirect indicator of IRE1α activation. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of how these pathways interplay and contribute to either cell survival or cell death is still lacking.

While the precise mechanisms underpinning the connection between IRE1α downstream pathways and immune infiltration remain elusive, prior studies have indicated that IRE1α can either promote immunosurveillance or facilitate immune system evasion through the regulation of damage-associated molecular patterns, cytokines, and the propagation of ER stress signals [23, 38]. We observed that heightened XBP1 and diminished MAPK8 expression correlated with elevated expression of immune cell meta-signatures which have previously been associated with unfavorable prognosis in glioblastoma [33]. These meta-signatures encompassed cell types such as macrophages, MDSC, Th1, and Treg. This result aligns with recent studies proposing a link between ER stress and the expression of immune cell markers in glioma patient samples [17, 47, 48]. Although the increase in expression is relatively modest, the CD8 T cell signature demonstrated a positive association with high XBP1 and low MAPK8. Notably, in prior studies, this meta-signature had only displayed a correlation with the survival of glioblastoma patients characterized by low immunosuppressive signatures [33]. Consequently, while the observed differential expression may suggest the presence of CD8 T cells, it does not necessarily provide insight into their activity and signaling context.

Furthermore, when analyzing single cell data, we noted that, although both XBP1 and MAPK8 were highly expressed in immune cells, the XBP1/MAPK8 expression ratio within tumor cells correlated strongly with the abundance of immune cells in each sample. This suggests a potential role for the IRE1α pathways in shaping the TME and influencing the infiltration of immune cell types that may potentiate immunosuppression and are typically associated with worse patient outcomes. Understanding the regulatory role of these genes in immune cell function within the glioblastoma microenvironment holds the potential to reveal novel approaches targeting the UPR. Such insights could contribute to enhancing antitumor immunity and complementing standard therapies as well as emerging immunotherapies. However, it is important to emphasize that a more in-depth investigation is warranted to substantiate these findings and elucidate the intricate mechanisms governing this relationship. Evaluating UPR protein expression in glioblastoma patient samples alongside other indicators of malignancy, like immune infiltration, as well as conducting studies that target these genes in in vitro and in vivo models, will be pivotal in advancing our understanding of the roles played by the UPR in glioblastoma.

Conclusions

In summary, we performed a comprehensive transcriptional characterization of the unfolded protein response in glioblastoma patients. Our study identified UPR-related genes associated with glioblastoma patient survival, providing potential prognostic and predictive biomarkers as well as promising targets for developing new therapeutic interventions in glioblastoma treatment.

Availability of data and materials

The scRNA-seq dataset is available in the GEO repository under accession number GSE131928. Firehouse Legacy and PanCancer Atlas datasets are available in the TCGA repository. Microarray expression data analysed during the current study are available in the GEO repository, under the accession numbers included in Table S3. The code to reproduce the analyses and figures described in this study can be found at www.github.com/fernandaoliveiraa/2022_GBMsinglecell.

Abbreviations

- ATF6:

-

Activating transcription factor 6

- ER:

-

Endoplasmic reticulum

- ERAD:

-

ER-associated degradation

- Gent2:

-

Gene Expression database of Normal and Tumor tissues 2

- GEO:

-

Gene Expression Omnibus

- IRE1α:

-

Inositol-requiring protein 1 alpha

- PERK:

-

Protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase

- scRNA-seq:

-

Single cell RNA sequencing

- TCGA:

-

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- TME:

-

Tumor microenvironment

- UPR:

-

Unfolded protein response

References

Hetz C, Chevet E, Oakes SA. Proteostasis control by the unfolded protein response. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:829–38.

Rutkowski DT, Kaufman RJ. That which does not kill me makes me stronger: adapting to chronic ER stress. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:469–76.

Walter P, Ron D. The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science. 1979;2011(334):1081–6.

Hetz C, Papa FR. The unfolded protein response and cell fate control. Mol Cell. 2018;69:169–81.

Pallud J, Audureau E, Noel G, Corns R, Lechapt-Zalcman E, Duntze J, et al. Long-term results of carmustine wafer implantation for newly diagnosed glioblastomas: a controlled propensity-matched analysis of a French multicenter cohort. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17:1609–19.

Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJB, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–96.

Pyrko P, Schönthal AH, Hofman FM, Chen TC, Lee AS. The unfolded protein response regulator GRP78/BiP as a novel target for increasing chemosensitivity in malignant gliomas. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9809–16.

Salaroglio IC, Panada E, Moiso E, Buondonno I, Provero P, Rubinstein M, et al. PERK induces resistance to cell death elicited by endoplasmic reticulum stress and chemotherapy. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:91.

Epple LM, Dodd RD, Merz AL, Dechkovskaia AM, Herring M, Winston BA, et al. Induction of the unfolded protein response drives enhanced metabolism and chemoresistance in glioma cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73267.

Kyani A, Tamura S, Yang S, Shergalis A, Samanta S, Kuang Y, et al. Discovery and mechanistic elucidation of a class of protein disulfide isomerase inhibitors for the treatment of glioblastoma. Chem Med Chem. 2018;13:164–77.

Xu S, Liu Y, Yang K, Wang H, Shergalis A, Kyani A, et al. Inhibition of protein disulfide isomerase in glioblastoma causes marked downregulation of DNA repair and DNA damage response genes. Theranostics. 2019;9:2282–98.

Xipell E, Aragón T, Martínez-Velez N, Vera B, Idoate MA, Martínez-Irujo JJ, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-inducing drugs sensitize glioma cells to temozolomide through downregulation of MGMT, MPG, and Rad51. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18:1109–19.

Obacz J, Avril T, le Reste P-J, Urra H, Quillien V, Hetz C, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum proteostasis in glioblastoma—from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic perspectives. Sci Signal. 2017;10:eaal2323.

Tsai S-F, Tao M, Ho L-I, Chiou T-W, Lin S-Z, Su H-L, et al. Isochaihulactone-induced DDIT3 causes ER stress-PERK independent apoptosis in glioblastoma multiforme cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8:4051–61.

Śledzińska P, Bebyn MG, Furtak J, Kowalewski J, Lewandowska MA. Prognostic and predictive biomarkers in gliomas. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:10373.

Graner MW, Raynes DA, Bigner DD, Guerriero V. Heat shock protein 70-binding protein 1 is highly expressed in high-grade gliomas, interacts with multiple heat shock protein 70 family members, and specifically binds brain tumor cell surfaces. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:1870–9.

Huang R, Li G, Wang K, Wang Z, Zeng F, Hu H, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the clinical and biological significances of endoplasmic reticulum stress in diffuse gliomas. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:619396.

Drogat B, Auguste P, Nguyen DT, Bouchecareilh M, Pineau R, Nalbantoglu J, et al. IRE1 signaling is essential for ischemia-induced vascular endothelial growth factor-a expression and contributes to angiogenesis and tumor growth in vivo. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6700–7.

Auf G, Jabouille A, Guerit S, Pineau R, Delugin M, Bouchecareilh M, et al. Inositol-requiring enzyme 1 is a key regulator of angiogenesis and invasion in malignant glioma. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107:15553–8.

Lhomond S, Avril T, Dejeans N, Voutetakis K, Doultsinos D, McMahon M, et al. Dual IRE1 RNase functions dictate glioblastoma development. EMBO Mol Med. 2018;10:e7929.

Pluquet O, Dejeans N, Bouchecareilh M, Lhomond S, Pineau R, Higa A, et al. Posttranscriptional regulation of PER1 underlies the oncogenic function of IREα. Cancer Res. 2013;73:4732–43.

Dowdell A, Marsland M, Faulkner S, Gedye C, Lynam J, Griffin CP, et al. Targeting XBP1 mRNA splicing sensitizes glioblastoma to chemotherapy. FASEB Bioadv. 2023;5:211–20.

Chen X, Cubillos-Ruiz JR. Endoplasmic reticulum stress signals in the tumour and its microenvironment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2021;21:71–88.

Obacz J, Avril T, Rubio-Patiño C, Bossowski JP, Igbaria A, Ricci J-E, et al. Regulation of tumor-stroma interactions by the unfolded protein response. FEBS J. 2019;286:279–96.

Neftel C, Laffy J, Filbin MG, Hara T, Shore ME, Rahme GJ, et al. An integrative model of cellular states, plasticity, and genetics for glioblastoma. Cell. 2019;178:835-849.e21.

Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data: Figure 1. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:401–4.

Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles Using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal. 2013;6:pl1.

Park S-J, Yoon B-H, Kim S-K, Kim S-Y. GENT2: an updated gene expression database for normal and tumor tissues. BMC Med Genomics. 2019;12:101.

Hao Y, Hao S, Andersen-Nissen E, Mauck WM, Zheng S, Butler A, et al. Integrated analysis of multimodal single-cell data. Cell. 2021;184:3573-3587.e29.

Kowalczyk MS, Tirosh I, Heckl D, Rao TN, Dixit A, Haas BJ, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals changes in cell cycle and differentiation programs upon aging of hematopoietic stem cells. Genome Res. 2015;25:1860–72.

Reich S, Nguyen CDL, Has C, Steltgens S, Soni H, Coman C, et al. A multi-omics analysis reveals the unfolded protein response regulon and stress-induced resistance to folate-based antimetabolites. Nat Commun. 2020;11:2936.

Symons KT, Massari ME, Dozier SJ, Nguyen PM, Jenkins D, Herbert M, et al. Inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase expression by a novel small molecule activator of the unfolded protein response. Curr Chem Genomics. 2008;2:1–9.

Pereira MB, Barros LRC, Bracco PA, Vigo A, Boroni M, Bonamino MH, et al. Transcriptional characterization of immunological infiltrates and their relation with glioblastoma patients overall survival. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7:e1431083.

Urano F, Wang X, Bertolotti A, Zhang Y, Chung P, Harding HP, et al. Coupling of stress in the ER to activation of JNK protein kinases by transmembrane protein kinase IRE1. Science. 1979;2000(287):664–6.

Nishitoh H, Matsuzawa A, Tobiume K, Saegusa K, Takeda K, Inoue K, et al. ASK1 is essential for endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced neuronal cell death triggered by expanded polyglutamine repeats. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1345–55.

Hwang J, Qi L. Quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum: crosstalk between ERAD and UPR pathways. Trends Biochem Sci. 2018;43:593–605.

Yoshida H, Matsui T, Yamamoto A, Okada T, Mori K. XBP1 mRNA is induced by ATF6 and spliced by IRE1 in response to ER stress to produce a highly active transcription factor. Cell. 2001;107:881–91.

Rubio-Patiño C, Bossowski JP, Chevet E, Ricci J-E. Reshaping the immune tumor microenvironment through IRE1 signaling. Trends Mol Med. 2018;24:607–14.

Cattaneo M, Baronchelli S, Schiffer D, Mellai M, Caldera V, Saccani GJ, et al. Down-modulation of SEL1L, an unfolded protein response and endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation protein, sensitizes glioma stem cells to the cytotoxic effect of valproic acid. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:2826–38.

Mellai M, Annovazzi L, Boldorini R, Bertero L, Cassoni P, De Blasio P, et al. SEL1L plays a major role in human malignant gliomas. J Pathol Clin Res. 2020;6:17–29.

Kappadakunnel M, Eskin A, Dong J, Nelson SF, Mischel PS, Liau LM, et al. Stem cell associated gene expression in glioblastoma multiforme: relationship to survival and the subventricular zone. J Neurooncol. 2010;96:359–67.

Wang Y, Zhao W, Xiao Z, Guan G, Liu X, Zhuang M. A risk signature with four autophagy-related genes for predicting survival of glioblastoma multiforme. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24:3807–21.

Hou X, Liu Y, Liu H, Chen X, Liu M, Che H, et al. PERK silence inhibits glioma cell growth under low glucose stress by blockage of p-AKT and subsequent HK2’s mitochondria translocation. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9065.

Ohoka N, Yoshii S, Hattori T, Onozaki K, Hayashi H. TRB3, a novel ER stress-inducible gene, is induced via ATF4–CHOP pathway and is involved in cell death. EMBO J. 2005;24:1243–55.

Wolford CC, McConoughey SJ, Jalgaonkar SP, Leon M, Merchant AS, Dominick JL, et al. Transcription factor ATF3 links host adaptive response to breast cancer metastasis. J Clin Investig. 2013;123:2893–906.

Ishihara S, Yasuda M, Ishizu A, Ishikawa M, Shirato H, Haga H. Activating transcription factor 5 enhances radioresistance and malignancy in cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6:4602–14.

Zhang Q, Guan G, Cheng P, Cheng W, Yang L, Wu A. Characterization of an endoplasmic reticulum stress-related signature to evaluate immune features and predict prognosis in glioma. J Cell Mol Med. 2021;25:3870–84.

Pan Y, Wang S, Yang B, Jiang Z, Lenahan C, Wang J, et al. Transcriptome analyses reveal molecular mechanisms underlying phenotypic differences among transcriptional subtypes of glioblastoma. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24:3901–16.

Acknowledgements

LCP received a CAPES fellowship and GL received a CNPq fellowship.

Funding

This work was done without formal funding sources.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FDO: Conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization. RPC: Conceptualization, writing—review & editing. LCP: Conceptualization, writing—review & editing. GL: Conceptualization, writing—review & editing, supervision. LBM: Conceptualization, writing – review & editing, supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 2:

Figure S1. Validation of the ER stress meta-signature. Figure S2. ER stress expression comparison between tumor and macrophages populations. Figure S3. Differential expression analysis of 25 UPR genes. Figure S4. Impact of individual UPR genes on patient survival. Figure S5. IRE1 downstream pathways have opposing roles in the presence of immune cells in TME.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oliveira, F.D., de Campos, R.P., Pereira, L.C. et al. Expression of key unfolded protein response genes predicts patient survival and an immunosuppressive microenvironment in glioblastoma. transl med commun 9, 5 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41231-024-00164-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41231-024-00164-0