Abstract

Until recent, there are no ideal small diameter vascular grafts available on the market. Most of the commercialized vascular grafts are used for medium to large-sized blood vessels. As a solution, vascular tissue engineering has been introduced and shown promising outcomes. Despite these optimistic results, there are limitations to commercialization. This review will cover the need for extrusion-based 3D cell-printing technique capable of mimicking the natural structure of the blood vessel. First, we will highlight the physiological structure of the blood vessel as well as the requirements for an ideal vascular graft. Then, the essential factors of 3D cell-printing including bioink, and cell-printing system will be discussed. Afterwards, we will mention their applications in the fabrication of tissue engineered vascular grafts. Finally, conclusions and future perspectives will be discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The need for an ideal small diameter vascular graft

Vascular autografts are widely used in treatment of vascular diseases and in surgeries such as tissue reconstruction and replantation. The first use of autologous artery was reported in 1896 [1]. Up till now, autografts are known as the gold standard of vascular replacement. Although autografts have various benefits including appropriate mechanical properties, the major drawback is the limited availability [2]. Since then, various synthetic vascular grafts were commercialized using Dacron, expanded poly(tetrafluoroethylene) (ePTFE), and polyurethane (PU) (Table 1) [3]. However, these FDA approved nondegradable synthetics may not be the best option due to the risk of thrombosis, intimal hyperplasia, and graft failure in small diameter environments [4,5,6,7]. Therefore, new approaches were needed to compensate the limitations of autologous and synthetic vascular grafts. By doing so, vascular tissue engineering (VTE) has emerged to bridge the gap [8,9,10,11,12].

The purpose of VTE is to develop tissue engineered tubular scaffolds mimicking the in vivo environment of the native blood vessels. One of the most important factors to imitate is the mechanical properties which should match with the host blood vessel. Low mechanical strength may lead to rupture of the graft due to the constant blood pressure, while high stiffness can cause compliance mismatch between the graft and the native blood vessel leading to intimal hyperplasia or atherosclerosis [18, 19]. Besides the mechanical properties, the diameter of the tubular scaffold should match to that of the host blood vessel. Size mismatch between the host and the transplanted vessels can cause uncontrolled turbulence or resistance [20, 21]. Other requirements are that the vascular graft should reduce the risk of thrombogenicity while enhancing the regenerative potentials [22].

Recently, advancements in tissue engineering have enabled mimicry of tissues and organs in a more precise manner. Especially, the introduction of 3D cell-printing allowed the deposition of cells accurately and uniformly in the desired region of the scaffold [23,24,25,26]. Through this technique, cell-encapsulated microtubular structures can be fabricated for VTE applications (Fig. 1). This review introduces the current development in tissue engineered vascular scaffolds created using extrusion-based 3D cell-printing technique.

Blood vessel structure and physiology

Prior to developing tissue engineered blood vessels, understanding of the structure and functions of the native blood vessels is the fundamental step. The native circulation system starts with the outflow of oxygen-rich blood through the aorta which branches into arteries to other organs and tissues. Arteries further branches into arterioles and then divide into capillaries, the smallest blood vessels. The actual interactions between local cells and blood such as nutrient supply and waste removal take place in the capillaries [27]. Then, the deoxygenated blood is collected by venules and further transported to veins which returns to the heart [28].

Types of the blood vessels and their structures

Arteries and veins are composed of three distinct layers: (1) tunica intima, (2) - media, and (3) - adventitia (Fig. 2). However, the thickness of the layers vary depending on their physiological role [29]. The tunica intima which is the inner layer is made up of endothelial cells (ECs) providing a pathway for frictionless flow of blood. This tight monolayer also functions for antithrombosis, anti-infection or -inflammation, and regulation of cells in other layers by detecting physicochemical and biological changes in the blood [30, 31]. The middle layer or tunica media responsible for integrity and mechanical strength of the blood vessel is composed of smooth muscle cells (SMCs) in circle of rows and elastic fibers [32, 33]. The outer layer, tunica adventitia, consists of fibroblasts, collagen, and elastic fibers forming the connective tissue. Most of the collagen fibrils are circumferentially oriented, while the fibrils on the surface are longitudinally oriented [34, 35]. This composition attributes to passive mechanical support including preventing overexpansion of the vessel [36]. The smaller vessels, arterioles and venules, are composed of two layers which are tunica intima and – media. Finally, capillaries are composed of a thin endothelialized mono-layer where the blood flow is the slowest [31].

The importance of ECM structure

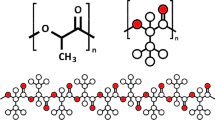

The two main building blocks of the vessel wall extracellular matrix (ECM) engaged in the mechanical properties are collagen and elastin [37,38,39]. Collagen is one of the most abundant protein in the body providing framework to tissues and organs [40]. Collagen has a triple-helical structure composed of three polypeptide chains which are held together by hydrogen bonds [41]. Fibrillar collagens are composed of fibers which are bundles of collagen fibrils. These fibrils are aggregates of the precursors called tropocollagen. Elastin is an insoluble hydrophobic protein found in the ECM providing various tissues with elasticity [42]. Elastogenesis is initiated by the expression of tropoelastin, a precursor of elastin, from a single human gene called ELN [43]. Then, these precursors are secreted into the extracellular space by vascular cells including SMCs, ECs, and fibroblasts. After the secretion, the soluble monomers experience a process known as coacervation. The coacervates attached to the cell surface undergo partial crosslinking and detach from the cell membrane. Further crosslinking results in the maturation of elastic fibers [44]. The elasticity and stiffness of the blood vessel is determined by the structure of the ECM. The difference in structure depends on their anatomic location which determine their functional role. For example, compared to veins and venules, the wall thickness of arteries and arterioles are relatively thicker in order to maintain the blood pressure and control the blood flow [45].

In general, the ECM serves as the scaffold providing stability and structural integrity to tissues and organs [46]. Moreover, the ECM allows information exchange with cells for the regulation of various cellular activities [47]. The ECM in the blood vessels attributes to various functions. Most importantly, the vascular ECM is engaged in the mechanical properties of the blood vessel [48]. The blood vessel is capable of bearing the mechanical forces driven by the everflowing blood owing to the ECM.

There are a few factors affecting the wall ECM structure including wall shear and circumferential stress. Wall shear stress is defined as the frictional force per unit area and circumferential or hoop stress is the force acting tangentially to the circumference exerted by the circulating blood flow on the intimal surface of the blood vessel [49, 50]. This can be explained using the Hagen-Poiseuille equation (shear stress (\(\tau ) =32\eta Q/\pi {d}^{3}\), where \(\eta\) indicates the mean viscosity, \(Q\) indicates the mean blood flow rate, and \(d\) indicates the vessel diameter) and hoop stress formula (circumferential stress (\(\sigma ) = Pd/2w\), where P indicates the internal pressure and w indicates the wall thickness) [51, 52]. High degree of shear and circumferential stress results in increased vessel wall thickness and diameter to maintain the normal shear stress value [53]. On the contrary, low value of stresses reduces the vessel diameter leading to intimal hyperplasia [53]. Likewise, these environmental changes trigger cellular activities as well as the remodeling of the blood vessel.

Requirements for vascular grafts

Until now, there are no obvious guidelines related to the data on the physical and chemical properties and performance of the biodegradable scaffold for vascular regeneration manufactured using a 3D bioprinter. Moreover, vascular graft with cells encapsulated are even more complicated. However, there are guidelines related to the data on the cardiovascular implants - tubular vascular prostheses (ISO 7198:2016) [54]. Typical evaluations performed on vascular grafts are burst pressure, compliance, and suture retention which are related to the mechanical properties (Fig. 3). Besides the physical characteristics, endothelialization is a crucial process in vascular regeneration.

Burst pressure

Burst pressure is one of the most important parameters since vascular grafts should withstand the hemodynamic pressures. Therefore, the vascular transplant must have sufficient strength to avoid rupture or permanent deformation. The greatest pressure before failure of the graft is termed the burst strength [55]. The burst strength can be calculated using the equation, \({P}_{\text{b}\text{u}\text{r}\text{s}\text{t}}= {\sigma }_{y} \times t/r\), where \({\sigma }_{y}\) defines the yield stress, \(t\) defines the wall thickness, and \(r\) defines the radius of the vascular graft. This equation shows that the burst pressure increases linearly with decreasing radius assumed that the wall thickness is constant. In general, the burst pressure is measured by pressurizing the vascular graft at 80–120 mmHg s− 1 until rupture, while the internal pressure is recorded (Fig. 3(a)). The maximum pressure at rupture is referred to as the burst pressure.

Compliance

Compliance mismatch between the host blood vessel and vascular graft can cause various side effects including intimal hyperplasia and occlusion due to hemodynamic flow changes across anastomosis [56,57,58]. Compliance measures the dimensional change of a graft over a change in internal pressure [59]. This can be described using the following equation, \(\%\text{c}\text{o}\text{m}\text{p}\text{l}\text{i}\text{a}\text{n}\text{c}\text{e} = \left(\frac{{r}_{{p}_{2}}- {r}_{{p}_{1}}}{{r}_{{p}_{1}}}/{p}_{2} - {p}_{1}\right)\times {10}^{4}\), in which r indicates the radius and p indicates the pressure. The most commonly used synthetic grafts (Dacron and ePTFE) causes compliance mismatch due to their rigid nature unlike the native tissue [60]. Therefore, it is crucial to use biomaterials closely mimicking the natural ECM of the vessel wall. Compliance of a vascular graft can be measured by applying constant load on the graft while pressurizing internally (Fig. 3(b)). Then, the dimensional changes can be recorded and processed to measure the compliance.

Suture retention

Suture is an essential surgical parameter in transplantation of artificial vascular grafts into the human body. Therefore, the transplanted graft should have enough strength to withstand the tensile load of the sutures without failure [61]. This is defined as the suture retention strength. To measure this strength, the prepared graft is cut from the middle. Then, they are sutured and pulled at a constant rate until rupture (Fig. 3(c)). The maximum tensile force is the suture retention strength.

Endothelialization

The absence of endothelial layer in vascular devices may lead to health complications due to side effects such as thrombosis [62]. Thus, the formation of this specialized layer (the endothelium) is a fundamental step after transplantation for successful vascular regeneration. Since the endothelium is composed of ECs, the surface topography of the graft should promote cell adhesion and migration [63, 64]. Therefore, the surface chemistry of the vascular graft has an important role in the formation of the endothelium. Some of the most widely used methods to functionalize the vascular graft surface are listed in Table 2.

Vascular tissue engineering

The intention of VTE is to guide cells to grow and mature into a functional blood vessel while the implanted graft is completely dissolved. 3D cell-printing is an emerging technology used in the field of tissue engineering capable of developing complex structures in high resolution mimicking the native environment of tissues and organs. 3D cell-printing process starts with the formulation of the bioink which is extruded through a small diameter nozzle attached to a 3D printing system.

Core technology: 3D cell-printing

3D cell-printing has revolutionized the field of TE in which carefully formulated bioink is extruded through the nozzle of a 3D cell-printing system to fabricate biological substitutes for tissue regeneration purposes. The replication of tissues and organs is a complex process, thereby 3D cell-printing systems should be highly accurate with high resolution. However, for high-resolution bioprinting small diameter nozzles are used in which the shear stress may cause low cell-viability. Prior to cell-printing, the printability of the bioink should be taken in consideration [74]. The printability is influenced by various parameters during the extrusion of the bioink. The flow behavior in the nozzle site can be described using the Herschel-Bulkley model, \(\tau = {\tau }_{0}+ \text{{\rm K}}{\gamma }^{n}\), where \(\tau\) defines shear stress, \({\tau }_{0}\) defines yield stress, \(\text{{\rm K}}\) defines consistency index, \(\gamma\) defines shear rate, and \(n\) defines shear-thinning parameter [75, 76]. As seen in the Herschel-Bulkley model, shear stress is a function of shear rate. The fact that shear stress increases the risk of damaging the cells within the bioink is ubiquitous in the cell-printing world. The shear rate occurring in the nozzle can be defined as \({\gamma }^{n}= {\left[{V}_{2}{R}_{2}^{2}/\left(\frac{n}{3n+1}\right)\left({R}_{2}^{\frac{3n+1}{n}}\right)\right]}^{n}r\), where \({V}_{2}\) defines the velocity of the extruded bioink, \({R}_{2}\) defines the inner radius of the nozzle, and \(r\) defines the radial distance from the axis of the nozzle [77]. The shear rate increases as the radial distance from the axis of the nozzle increases meaning that the shear stress also increases. The shear stress is greater in the area closer to the wall of the nozzle causing the greatest cell damage which can lead to cell death (Fig. 4(a)).

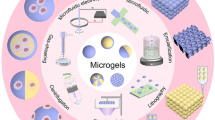

Core resource: Bioink

Bioink is the core resource composed of printable biomaterials, viable cells, and other biological components essential for 3D cell-printing. Bioink should fulfill the physiological and physiochemical requirements associated with the printing process and the activities of the cells. Cell-friendly properties including biocompatibility, cytocompatibility, and bioactivity of the material are factors essential for obtaining high cell viability. Furthermore, rheological properties of the biomaterial play an important role not only in the viability of cells but also in the printability of cell-printing process. In short, an ideal bioink should be highly printable with high shape fidelity, protect cells from mechanical stress to maintain high cell viability, and provide biological cues to direct cellular activities (Fig. 4(b)). Some of the widely used biomaterials are listed in Table 3.

The key rheological parameters with the greatest influence on the cell-printing process are viscosity, yield stress, shear thinning, and viscoelasticity [93,94,95]. Viscosity is referred to the resistance to flow of a fluid under the application of stress. In general, highly viscous materials provide greater printability. However, increased viscosity causes increased shear stress in the printing nozzle which may negatively influence the viable cells in the bioink. On the contrary, low viscosity results in decreased printability leading to a poor shape maintenance after the printing process. Therefore, shear thinning behavior is important in extrusion-based printing systems. At rest, the molecular chains of the biomaterial are entangled and randomly oriented. When exposed to shear stress, the chains disentangle and orient along the shear flow. This behavior is called shear thinning, a phenomenon in which the viscosity decreases under shear stress [96]. Shear thinning behavior allows the ease of extrusion without harming the cells. Moreover, the decreased shear rate after the extrusion causes a rise in viscosity contributing to the shape preservation of the printed structure. During the extrusion through a nozzle, the bioink undergo viscous flow and elastic shape retention. This property is known as the viscoelasticity which can be determined using the storage modulus (G′) and the loss modulus (G″) [95]. G′ indicates the measurement of the energy stored elastically during deformation and G″ indicates the measurement of energy dissipated by the biomaterial. The G″/G′ ratio is defined as the loss tangent (tan(d)), which determines the state of the biomaterial. Greater values of tan(d) attribute to the extrusion uniformity, while lower values impact the shape fidelity. It is often overlooked the fact that cells within the bioink may alter the rheological properties [97,98,99,100]. Since cells occupy a certain volume, they can act as an obstacle hindering the crosslinking efficiency and chemical events. Therefore, the number of cells used should be considered.

3D cell-printing in vascular tissue regeneration

The anatomy and physiological conditions of tissues and organs differ from patient to patient. Therefore, patient-specific vascular grafts are highly demanded to prevent possible side effects after the transplantation. Using 3D cell-printing technology, tailor-made vascular grafts can be manufactured mimicking the native structure of the blood vessel. Besides graft production, 3D cell-printing can be utilized in other applications including vessel-on-a-chip.

Efforts towards ideal tissue engineered vascular grafts

The first attempt was in 1986 where a multilayered tube was developed using collagen and a Dacron mesh [101]. Three types of cells (bovine aortic ECs, SMCs, and adventitial fibroblasts) were used to mimic the tri-layered structure of the blood vessel. The Dacron mesh was needed to compensate the weak strength of collagen. Unfortunately, despite the reinforcement, in vivo implantation was not possible due to low burst strength. In 1999, poly(glycolic acid) (PGA), a semi-crystalline synthetic polymer, and SMCs were used to develop a tissue engineered arteries [102]. A bioreactor with the ability to apply pulsatile radial stress improved the mechanical strength of the vascular structure. However, some challenges remained including polymer remnants after the implantation and lack of mature elastin on the developed vascular graft. Since then, various techniques have been employed to develop implantable grafts for vascular tissue regeneration.

Cell-printed vascular grafts and other

Various approaches towards extrusion-based 3D cell-printing of vascular grafts have been proposed. A simple method is to print a structure in a layer-by-layer manner. Gold et al. attempted to build a free-standing cylindrical vascular structure composed of gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA), polyethylene(glycol)diacrylate (PEGDA), and nanosilicates (nSi) using an extrusion-based cell-printing system (Fig. 5(a)) [103]. The cell-printed structure consisted of vascular smooth muscle cells (vSMCs) was stabilized through a subsequent crosslinking via UV light. Afterwards, ECs were seeded in the core region of the structure to replicate the natural structure of the blood vessel. Both cell types in the printed structure showed high rate of viable cells and phenotypic maintenance over time. Furthermore, cell-to-cell interaction was studied by assessing the EC barrier disruption and permeability to the underlying layer in a stimulated and healthy group. As a result, this vascular replica was able to mimic the in vivo thrombo-inflammatory responses. As another example, Tabriz et al. designed a branched vascular structure using a modified bioprinting technique in which the printing stage was able to displace in the z-direction [104]. As seen in Fig. 5(b), the cell-laden alginate bioink was crosslinked by submerging the structure into a CaCl2 bath by lowering the stage. To extend long term integrity, the printed structure was further crosslinked in barium chloride.

Fabrication of tubular vascular grafts using a layer-by-layer extrusion-based 3D cell-printing technique. Images showing production of (a) two-layered tubular structure for thrombo-inflammatory studies and (b) branched vascular structure. Reproduced from [103, 104] with permission from Wiley–VCH Copyright 2021 and IOP Publishing Copyright 2015

One of the most efficient and promising extrusion-based cell-printing strategy in producing tubular structures is the core-shell printing method. This method allows the use of multiple bioinks with different cell types to simulate the blood vessel structure. Colosi and coworkers developed a structure composed of tubular struts laden with human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) [105]. A coaxial nozzle attached to a 3D bioprinter was employed where GelMA, alginate, and photoinitiator was extruded through the inner nozzle and CaCl2 solution was flown through the outer nozzle to ionically crosslink the alginate chains (Fig. 6(a)). Afterwards, the printed structure was UV crosslinked to stabilize the GelMA prepolymer. The bioprinted HUVECs colonized at the edge of the struts forming a vessel-like structure after 10 days. Moreover, the cells were uniaxially aligned forming a monolayer mimicking the structure of the native blood vessel. However, vascular grafts fabricated in the above-mentioned examples lack the mechanical properties which do not match the standards for burst pressure and suture retention strength.

In another study, a high-strength small diameter vascular graft was manufactured using a core-shell extrusion printing system [106]. The biomaterials used are nanoclay, N-acryloyl glycinamide (NAGA), and GelMA (Fig. 6(b)). The amount of nanoclay was fixed at 100 mg, while the amount of NAGA and GelMA were varied. The mechanical strength was dependent on the ratio between NAGA and GelMA. Greater content of NAGA resulted in enhanced mechanical strength. Also, greater burst pressure and suture retention strength was achieved compared to the native tissue. A burst pressure of ≈ 1500–2500 mmHg was achieved which was in the range of the standard for autologous vascular graft. Moreover, the suture retention strength of the fabricated graft (≈ 280 gf) was significantly greater than that of the human saphenous vein (196 ± 2 gf) [108]. Besides physical properties, the designed tubular graft showed outstanding biocompability. In a study of Zhou et al., a small-diameter blood vessel composed of two different cell layers was fabricated using a core-shell printing system [107]. To obtain the lumen structure, F-127 was used to leach out the core of the printed vessel. In the shell region, vSMCs were embedded in the bioink composed of GelMA/PEGDA/alginate/lyase. For the stabilization of the printed structure, alginate was ionically crosslinked using CaCl2 solution and GelMA/PEGDA was photo-crosslinked using a UV laser. Finally, vascular endothelial cells (vECs) encapsulated in gelatin were injected in the core region. This process is shown in Fig. 6(c). The cell-laden structure was perfusable under various conditions (flow velocity, flow viscosity, and temperature). The fabricated structure was considered to have similar elasticity properties (compliance) of real blood vessels under various physiological conditions. Furthermore, lyase in the bioink accelerated the degradation of alginate which provided space for the cells to proliferate.

A similar coaxial bioextrusion method was used to fabricate an in vitro vasculature model [109]. Vasculature is an essential part in organ-on-a-chip development for replacing animal testing and studying the human body. First, a polymeric chamber was printed using poly(ethylene-co-vinyl acetate) (PEVA) before cell-printing the vessel composed of alginate, vascular-tissue-derived extracellular matrix (vECM), and HUVECs. The next step is the maturation of the cell-printed vessel where an endothelial monolayer is formed. This vascular model can be used for studying the pathological changes during the process of inflammatory diseases.

In vivo applications of cell-printed vascular grafts

Gao et al. engineered a tubular structure composed of atorvastatin-loaded poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid (PLGA) microspheres/vECM/alginate with endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) [110]. In this process, a coaxial cell-printing method was used where pluronic F-127 was used in the core region as a sacrificial material to create the tubular structure (Fig. 7(a)). This vascular structure was transplanted into a nude mice hind limb to study the therapeutic effect on the ischemic disease. Reduced limb loss, foot necrosis, and toe loss was observed in the group transplanted with the fabricated vascular structure. In addition, increased neovascularization was discovered at the injury site when transplanted with the cell-printed structure. This research group also attempted to mimic the structure of the natural blood vessel using a triple-coaxial cell printing system as seen in Fig. 7(b) [111]. The bioink used in their study was composed of alginate and vECM. To create the outer layer, vSMCs were encapsulated in the bioink. For the inner layer, vECs were embedded in the bioink. The tubular structure was formed by leaching out the PF-127 in the core. After culturing the cell-laden structure in a bioreactor system, it was implanted in rat abdominal aorta and observed for three weeks. As a result, the tissue engineered vascular graft showed promising results including great patency, well-retained endothelium, matured smooth muscles, and integration with host tissues.

Requirements for commercialization

One of the most significant hurdles for commercialization of tissue engineered vascular graft is to get the approval by governmental organizations such as Food and Drug Administration (FDA). One of the requirements is that the vascular graft should be fabricated under good manufacturing practice (GMP) conditions. GMP involves the manufacturing and management of the medicinal products according to the quality standards for product approval. Therefore, the 3D bioprinting systems should be GMP grade and placed in GMP facilities operated by trained authorities. Moreover, the biomaterials used to fabricate the grafts should get approved or be on the list of approved materials. After the production process, the vascular grafts should pass various safety tests including biocompatibility test (ISO 10,993), chemical-physical and performance test (ISO 7198:2007, ISO 25539-1:2010, and ISO 15676:2005), and pre-clinical test (Good Laboratory Practice (GLP)). Finally, the last step prior to approval is the clinical trial (ISO 14,155). This whole approval process might be enduring and costly. The estimated time for FDA approval when it comes to a tissue engineered vascular graft is approximately 10 years.

Conclusions and future perspectives

As mentioned in this review, autografts remain the gold standard for blood vessel regeneration. However, shortage in supply has forced to search for an alternative. As a solution, 3D cell-printing technology has been introduced capable of producing vascular grafts using cell encapsulated bioink. An ideal vascular graft should closely mimic the structure and function of the natural blood vessel. For this purpose, the cell-printing system and bioink should be optimized. The printing system should be able to simulate the three-layered structure of the blood vessels. Moreover, the bioink should protect cells against the shear stress inside the nozzle and provide appropriate environment to guide the cells. For clinical applications, the fabricated vascular graft should withstand the blood pressure, match the compliance with that of the host tissue, and bear the tensile load of the sutures during implantation. Despite of the advances in 3D cell-printing technology, there are still some hurdles to overcome.

One of the most critical challenges is to enhance the mechanical strength of the biomaterials used for cell-printing. In general, bioinks are composed of hydrogels to encapsulate viable cells harmlessly. However, one limitation of these vascular structures is the mechanical properties which were not in the range of a native vessel. Another challenge is the multi-cell culture since various cells are embedded in the vascular graft. Therefore, the multi-cell culture should be optimized to provide proper environment and induce cell differentiation/maturation. In terms of commercialization, some practical challenges exist to overcome. Commercial-grade production process is far more complicated when cells are involved. First, good manufacturing practice (GMP) production facilities are required. Second, the shell life of the vascular graft should be above the minimum standard. Third, the maintenance & storage problems should be solved. To this end, solution to these limitations is needed to provide patients suffering from vascular diseases with commercially available products.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in published article.

Abbreviations

- ePTFE:

-

expanded poly(tetrafluoroethylene)

- VTE:

-

vascular tissue engineering

- SMCs:

-

smooth muscle cells

- ECs:

-

endothelial cells

- ECM:

-

extracellular matrix

- G′:

-

storage modulus

- G″:

-

loss modulus

- PGA:

-

poly(glycolic acid)

- GelMA:

-

gelatin methacryloyl

- PEGDA:

-

polyethylene(glycol)diacrylate

- nSi:

-

nanosilicates

- HUVECs:

-

human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- vSMCs:

-

vascular smooth muscle cells

- NAGA:

-

N-acryloyl glycinamide

- vECS:

-

vascular endothelial cells

- PEVA:

-

poly(ethylene-co-vinyl acetate)

- vECM:

-

vascular-tissue-derived extracellular matrix

- PLGA:

-

atorvastatin-loaded poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid

- EPCs:

-

endothelial progenitor cells

- GMP:

-

good manufacturing practice

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- GLP:

-

Good Laboratory Practice

References

Konner K. History of vascular access for haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20(12):2629–35.

L’heureux N, Dusserre N, Marini A, Garrido S, De La Fuente L, McAllister T. Technology insight: the evolution of tissue-engineered vascular grafts—from research to clinical practice. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2007;4(7):389–95.

Xue L, Greisler HP. Biomaterials in the development and future of vascular grafts. J Vasc Surg. 2003;37(2):472–80.

Sarkar S, Salacinski H, Hamilton G, Seifalian A. The mechanical properties of infrainguinal vascular bypass grafts: their role in influencing patency. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;31(6):627–36.

Hamad OA, Bäck J, Nilsson PH, Nilsson B, Ekdahl KN. Platelets, complement, and contact activation: partners in inflammation and thrombosis. New York: Springer; 2012. pp. 185–205.

Gorbet MB, Sefton MV. Biomaterial-associated thrombosis: roles of coagulation factors, complement, platelets and leukocytes. Biomaterials. 2004;25(26):5681–703.

Park S, Kim J, Lee M-K, Park C, Jung H-D, Kim H-E, Jang T-S. Fabrication of strong, bioactive vascular grafts with PCL/collagen and PCL/silica bilayers for small-diameter vascular applications. Mater Des. 2019;181:108079.

Fleischer S, Tavakol DN, Vunjak-Novakovic G. From arteries to capillaries: approaches to engineering human vasculature. Adv Funct Mater. 2020;30(37):1910811.

Hann SY, Cui H, Esworthy T, Miao S, Zhou X, Lee SJ, Fisher JP, Zhang LG. Recent advances in 3D printing: vascular network for tissue and organ regeneration. Transl Res. 2019;211:46–63.

Lee H, Jang TS, Han G, Kim HW, Jung HD. Freeform 3D printing of vascularized tissues: Challenges and strategies. J Tissue Eng. 2021;12:20417314211057236.

Wang P, Sun Y, Shi X, Shen H, Ning H, Liu H. 3D printing of tissue engineering scaffolds: a focus on vascular regeneration. Bio-Des Manuf. 2021;4(2):344–78.

Fernández-Colino A, Wolf F, Rütten S, Schmitz-Rode T, Rodríguez-Cabello JC, Jockenhoevel S, Mela P. Small caliber compliant vascular grafts based on elastin-like recombinamers for in situ tissue engineering. Front bioeng biotechnol. 2019;7:340.

Sobh M, Voges I, Attmann T, Scheewe J. Prosthetic graft replacement of a large subclavian aneurysm in a child with Loeys–Dietz syndrome: a case report. Eur Heart J - Case Rep. 2020;4(5):1.

Begovac P, Thomson R, Fisher J, Hughson A, Gällhagen A. Improvements in GORE-TEX® Vascular Graft performance by Carmeda® bioactive surface heparin immobilization. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2003;25(5):432–7.

Lindsey P, Echeverria A, Cheung M, Kfoury E, Bechara CF, Lin PH. Lower extremity bypass using bovine carotid artery graft (artegraft): an analysis of 124 cases with long-term results. World J Surg. 2018;42(1):295–301.

Zehr BP, Niblick CJ, Downey H, Ladowski JS. Limb salvage with CryoVein cadaver saphenous vein allografts used for peripheral arterial bypass: role of blood compatibility. Ann Vasc Surg. 2011;25(2):177–81.

Chemla E, Morsy M. Randomized clinical trial comparing decellularized bovine ureter with expanded polytetrafluoroethylene for vascular access. J Br Surg. 2009;96(1):34–9.

Salacinski HJ, Goldner S, Giudiceandrea A, Hamilton G, Seifalian AM, Edwards A, Carson RJ. The mechanical behavior of vascular grafts: a review. J Biomater Appl. 2001;15(3):241–78.

Li X, Zhao H. Mechanical and degradation properties of small-diameter vascular grafts in an in vitro biomimetic environment. J Biomater Appl. 2019;33(8):1017–34.

Lyman D, Fazzio F, Voorhees H, Robinson G, Albo D Jr. Compliance as a factor effecting the patency of a copolyurethane vascular graft. J Biomed Mater Res. 1978;12(3):337–45.

Post A, Diaz-Rodriguez P, Balouch B, Paulsen S, Wu S, Miller J, Hahn M, Cosgriff-Hernandez E. Elucidating the role of graft compliance mismatch on intimal hyperplasia using an ex vivo organ culture model. Acta Biomater. 2019;89:84–94.

Sarkar S, Sales KM, Hamilton G, Seifalian AM. Addressing thrombogenicity in vascular graft construction. J Biomed Mater Res Part B Appl Biomater. 2007;82(1):100–8.

Lee HJ, Koo YW, Yeo M, Kim SH, Kim GH. Recent cell printing systems for tissue engineering. Int J Bioprint. 2017;3(1):004.

Unagolla JM, Jayasuriya AC. Hydrogel-based 3D bioprinting: a comprehensive review on cell-laden hydrogels, bioink formulations, and future perspectives. Appl Mater Today. 2020;18:100479.

Hull SM, Brunel LG, Heilshorn SC. 3D bioprinting of Cell-Laden Hydrogels for Improved Biological functionality. Adv Mater. 2022;34(2):2103691.

Kolesky DB, Truby RL, Gladman AS, Busbee TA, Homan KA, Lewis JA. 3D bioprinting of vascularized, heterogeneous cell-laden tissue constructs. Adv Mater. 2014;26(19):3124–30.

Townsley MI. Structure and composition of pulmonary arteries, capillaries and veins. Compr Physiol. 2012;2:675.

MacColl E, Khalil RA. Matrix metalloproteinases as regulators of vein structure and function: implications in chronic venous disease. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2015;355(3):410–28.

Zhang WJ, Liu W, Cui L, Cao Y. Tissue engineering of blood vessel. J Cell Mol Med. 2007;11(5):945–57.

Milutinović A, Šuput D, Zorc-Pleskovič R. Pathogenesis of atherosclerosis in the tunica intima, media, and adventitia of coronary arteries: an updated review. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2020;20(1):21.

Pugsley M, Tabrizchi R. The vascular system: an overview of structure and function. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2000;44(2):333–40.

Shen H, Hu X, Cui H, Zhuang Y, Huang D, Yang F, Wang X, Wang S, Wu D. Fabrication and effect on regulating vSMC phenotype of a biomimetic tunica media scaffold. J Mater Chem B. 2016;4(47):7689–96.

Seidel CL. Cellular heterogeneity of the vascular tunica media: implications for vessel wall repair. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17(10):1868–71.

Smith JH, Canham PB, Starkey J. Orientation of collagen in the tunica adventitia of the human cerebral artery measured with polarized light and the universal stage. J Ultrastruct Res. 1981;77(2):133–45.

Patel B, Xu Z, Pinnock CB, Kabbani LS, Lam MT. Self-assembled collagen-fibrin hydrogel reinforces tissue engineered adventitia vessels seeded with human fibroblasts. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1–13.

Maiellaro K, Taylor WR. The role of the adventitia in vascular inflammation. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75(4):640–8.

Bank AJ, Kaiser DR. Arterial wall mechanics. Berlin: Springer; 2002. pp. 151–61.

Bank AJ, Wang H, Holte JE, Mullen K, Shammas R, Kubo SH. Contribution of collagen, elastin, and smooth muscle to in vivo human brachial artery wall stress and elastic modulus. Circulation. 1996;94(12):3263–70.

Burton AC. Relation of structure to function of the tissues of the wall of blood vessels. Physiol Rev. 1954;34(4):619–42.

Aszodi A, Legate KR, Nakchbandi I, Fässler R. What mouse mutants teach us about extracellular matrix function. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:591–621.

Shoulders MD, Raines RT. Collagen structure and stability. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:929–58.

Hoeve C, Flory P. The Elastic Properties of Elastin1, 2. J Am Chem Soc. 1958;80(24):6523–6.

Tassabehji M, Metcalfe K, Donnai D, Hurst J, Reardon W, Burch M, Read AP. Elastin: genomic structure and point mutations in patients with supravalvular aortic stenosis. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6(7):1029–36.

Wang R, de Kort BJ, Smits AI, Weiss AS. Elastin in vascular grafts. Cham: Springer; 2020. pp. 379–410.

Armentano RL, Fischer EIC, Cymberknop LJ. Structural basis of the circulatory system. Bristol: IOP Publishing; 2019.

Yue B. Biology of the extracellular matrix: an overview. J Glaucoma. 2014;23:S20.

Hayden MR, Sowers JR, Tyagi SC. The central role of vascular extracellular matrix and basement membrane remodeling in metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: the matrix preloaded. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2005;4(1):1–20.

Eble JA, Niland S. The extracellular matrix of blood vessels. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15(12):1385–400.

Katritsis D, Kaiktsis L, Chaniotis A, Pantos J, Efstathopoulos EP, Marmarelis V. Wall shear stress: theoretical considerations and methods of measurement. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2007;49(5):307–29.

Back MR, White RA. Biomaterials: considerations for endovascular devices. New York: Springer; 1999. pp. 141–63.

Papaioannou TG, Stefanadis C. Vascular wall shear stress: basic principles and methods. Hell J Cardiol. 2005;46(1):9–15.

Pries A, Secomb T. Control of blood vessel structure: insights from theoretical models. Am J Physiol - Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288(3):H1010–5.

Zarins CK, Zatina MA, Giddens DP, Ku DN, Glagov S. Shear stress regulation of artery lumen diameter in experimental atherogenesis. J Vasc Surg. 1987;5(3):413–20.

Organisation internationale de normalisation. International Organization for Standardization. 2016.

Nagiah N, Johnson R, Anderson R, Elliott W, Tan W. Highly compliant vascular grafts with gelatin-sheathed coaxially structured nanofibers. Langmuir. 2015;31(47):12993–3002.

Jeong Y, Yao Y, Yim EK. Current understanding of intimal hyperplasia and effect of compliance in synthetic small diameter vascular grafts. Biomater Sci. 2020;8(16):4383–95.

Weston MW, Rhee K, Tarbell JM. Compliance and diameter mismatch affect the wall shear rate distribution near an end-to-end anastomosis. J Biomech. 1996;29(2):187–98.

Kassab GS, Navia JA. Biomechanical considerations in the design of graft: the homeostasis hypothesis. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2006;8:499–535.

Sonoda H, Takamizawa K, Nakayama Y, Yasui H, Matsuda T. Small-diameter compliant arterial graft prosthesis: design concept of coaxial double tubular graft and its fabrication. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;55(3):266–76.

Greisler HP, Joyce KA, Kim DU, Pham SM, Berceli SA, Borovetz HS. Spatial and temporal changes in compliance following implantation of bioresorbable vascular grafts. J Biomed Mater Res. 1992;26(11):1449–61.

Pensalfini M, Meneghello S, Lintas V, Bircher K, Ehret AE, Mazza E. The suture retention test, revisited and revised. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2018;77:711–7.

Baiguera S, Ribatti D. Endothelialization approaches for viable engineered tissues. Angiogenesis. 2013;16(1):1–14.

Franco D, Klingauf M, Bednarzik M, Cecchini M, Kurtcuoglu V, Gobrecht J, Poulikakos D, Ferrari A. Control of initial endothelial spreading by topographic activation of focal adhesion kinase. Soft Matter. 2011;7(16):7313–24.

Liliensiek SJ, Wood JA, Yong J, Auerbach R, Nealey PF, Murphy CJ. Modulation of human vascular endothelial cell behaviors by nanotopographic cues. Biomaterials. 2010;31(20):5418–26.

de Valence S, Tille JC, Chaabane C, Gurny R, Bochaton-Piallat M-L, Walpoth BH, Möller M. Plasma treatment for improving cell biocompatibility of a biodegradable polymer scaffold for vascular graft applications. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2013;85(1):78–86.

Park C, Park S, Kim J, Han A, Ahn S, Min SK, Jae HJ, Chung JW, Lee J-H, Jung H-D. Enhanced endothelial cell activity induced by incorporation of nano-thick tantalum layer in artificial vascular grafts. Appl Surf Sci. 2020;508:144801.

Pohan G, Chevallier P, Anderson DE, Tse JW, Yao Y, Hagen MW, Mantovani D, Hinds MT, Yim EK. Luminal plasma treatment for small diameter polyvinyl alcohol tubular scaffolds. Front bioeng biotechnol. 2019;7:117.

Wei Y, Wu Y, Zhao R, Zhang K, Midgley AC, Kong D, Li Z, Zhao Q. MSC-derived sEVs enhance patency and inhibit calcification of synthetic vascular grafts by immunomodulation in a rat model of hyperlipidemia. Biomaterials. 2019;204:13–24.

Choi WS, Joung YK, Lee Y, Bae JW, Park HK, Park YH, Park J-C, Park KD. Enhanced patency and endothelialization of small-caliber vascular grafts fabricated by coimmobilization of heparin and cell-adhesive peptides. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8(7):4336–46.

Shin YM, Lee YB, Kim SJ, Kang JK, Park J-C, Jang W, Shin H. Mussel-inspired immobilization of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) for enhanced endothelialization of vascular grafts. Biomacromolecules. 2012;13(7):2020–8.

De Visscher G, Mesure L, Meuris B, Ivanova A, Flameng W. Improved endothelialization and reduced thrombosis by coating a synthetic vascular graft with fibronectin and stem cell homing factor SDF-1α. Acta Biomater. 2012;8(3):1330–8.

Hoshi RA, Van Lith R, Jen MC, Allen JB, Lapidos KA, Ameer G. The blood and vascular cell compatibility of heparin-modified ePTFE vascular grafts. Biomaterials. 2013;34(1):30–41.

Xing Y, Gu Y, Guo L, Guo J, Xu Z, Xiao Y, Fang Z, Wang C, Feng Z-G, Wang Z. Gelatin coating promotes in situ endothelialization of electrospun polycaprolactone vascular grafts. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2021;32(9):1161–81.

Jang TS, Jung HD, Pan HM, Han WT, Chen S, Song J. 3D printing of hydrogel composite systems: recent advances in technology for tissue engineering. Int J Bioprinting. 2018;4(1):126.

Sarker M, Chen X. Modeling the flow behavior and flow rate of medium viscosity alginate for scaffold fabrication with a three-dimensional bioplotter. J Manuf Sci Eng. 2017;139(8).

Chimene D, Peak CW, Gentry JL, Carrow JK, Cross LM, Mondragon E, Cardoso GB, Kaunas R, Gaharwar AK. Nanoengineered ionic–covalent entanglement (NICE) bioinks for 3D bioprinting. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10(12):9957–68.

Hasturk O, Kaplan DL. Cell armor for protection against environmental stress: advances, challenges and applications in micro-and nanoencapsulation of mammalian cells. Acta Biomater. 2019;95:3–31.

Abasalizadeh F, Moghaddam SV, Alizadeh E, Kashani E, Fazljou SMB, Torbati M, Akbarzadeh A. Alginate-based hydrogels as drug delivery vehicles in cancer treatment and their applications in wound dressing and 3D bioprinting. J Biol Eng. 2020;14(1):1–22.

Smidsrød O, Skja G. Alginate as immobilization matrix for cells. Trends Biotechnol. 1990;8:71–8.

Yang JS, Xie YJ, He W. Research progress on chemical modification of alginate: a review. Carbohydr Polym. 2011;84(1):33–9.

Pellá MC, Lima-Tenório MK, Tenório-Neto ET, Guilherme MR, Muniz EC, Rubira AF. Chitosan-based hydrogels: from preparation to biomedical applications. Carbohydr Polym. 2018;196:233–45.

Singh BK, Sirohi R, Archana D, Jain A, Dutta P. Porous chitosan scaffolds: a systematic study for choice of crosslinker and growth factor incorporation. Int J Polym Mater Polym Biomater. 2015;64(5):242–52.

Bhattarai N, Gunn J, Zhang M. Chitosan-based hydrogels for controlled, localized drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62(1):83–99.

Chandy T, Sharma CP. Chitosan-as a biomaterial. Biomater Artif Cells Artif Organs. 1990;18(1):1–24.

Lee CH, Singla A, Lee Y. Biomedical applications of collagen. Int J Pharm. 2001;221(1–2):1–22.

Kühn K. The classical collagens: types I, II, and III. Orlando: Academic Press; 1987. pp. 1–37.

Aper T, Wilhelmi M, Gebhardt C, Hoeffler K, Benecke N, Hilfiker A, Haverich A. Novel method for the generation of tissue-engineered vascular grafts based on a highly compacted fibrin matrix. Acta Biomater. 2016;29:21–32.

Gui L, Boyle MJ, Kamin YM, Huang AH, Starcher BC, Miller CA, Vishnevetsky MJ, Niklason LE. Construction of tissue-engineered small-diameter vascular grafts in fibrin scaffolds in 30 days. Tissue Eng Part A. 2014;20(9–10):1499–507.

Shaikh FM, Callanan A, Kavanagh EG, Burke PE, Grace PA, McGloughlin TM. Fibrin: a natural biodegradable scaffold in vascular tissue engineering. Cells Tissues Organs. 2008;188(4):333–46.

Elsayed Y, Lekakou C, Labeed F, Tomlins P. Fabrication and characterisation of biomimetic, electrospun gelatin fibre scaffolds for tunica media-equivalent, tissue engineered vascular grafts. Mater Sci Eng C. 2016;61:473–83.

Lepidi S, Grego F, Vindigni V, Zavan B, Tonello C, Deriu G, Abatangelo G, Cortivo R. Hyaluronan biodegradable scaffold for small-caliber artery grafting: preliminary results in an animal model. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;32(4):411–7.

Lepidi S, Abatangelo G, Vindigni V, Deriu GP, Zavan B, Tonello C, Cortivo R. In vivo regeneration of small-diameter (2 mm) arteries using a polymer scaffold. FASEB J. 2006;20(1):103–5.

Cooke ME, Rosenzweig DH. The rheology of direct and suspended extrusion bioprinting. APL Bioeng. 2021;5(1):011502.

Kyle S, Jessop ZM, Al-Sabah A, Whitaker IS. ‘Printability’of candidate biomaterials for extrusion based 3D printing: state‐of‐the‐art. Adv Healthc Mater. 2017;6(16):1700264.

Schwab A, Levato R, D’Este M, Piluso S, Eglin D, Malda J. Printability and shape fidelity of bioinks in 3D bioprinting. Chem Rev. 2020;120(19):11028–55.

Wilson SA, Cross LM, Peak CW, Gaharwar AK. Shear-thinning and thermo-reversible nanoengineered inks for 3D bioprinting. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9(50):43449–58.

Diamantides N, Dugopolski C, Blahut E, Kennedy S, Bonassar LJ. High density cell seeding affects the rheology and printability of collagen bioinks. Biofabrication. 2019;11(4):045016.

Zhao Y, Li Y, Mao S, Sun W, Yao R. The influence of printing parameters on cell survival rate and printability in microextrusion-based 3D cell printing technology. Biofabrication. 2015;7(4):045002.

Schwartz R, Malpica M, Thompson GL, Miri AK. Cell encapsulation in gelatin bioink impairs 3D bioprinting resolution. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2020;103:103524.

Rutz AL, Lewis PL, Shah RN. Toward next-generation bioinks: tuning material properties pre-and post-printing to optimize cell viability. MRS Bull. 2017;42(8):563–70.

Weinberg CB, Bell E. A blood vessel model constructed from collagen and cultured vascular cells. Science. 1986;231(4736):397–400.

Niklason L, Gao J, Abbott W, Hirschi K, Houser S, Marini R, Langer R. Functional arteries grown in vitro. Science. 1999;284(5413):489–93.

Gold KA, Saha B, Rajeeva Pandian NK, Walther BK, Palma JA, Jo J, Cooke JP, Jain A, Gaharwar AK. 3D Bioprinted Multicellular Vascular Models. Adv Healthc Mater. 2021;10(21):2101141.

Tabriz AG, Hermida MA, Leslie NR, Shu W. Three-dimensional bioprinting of complex cell laden alginate hydrogel structures. Biofabrication. 2015;7(4):045012.

Colosi C, Shin SR, Manoharan V, Massa S, Costantini M, Barbetta A, Dokmeci MR, Dentini M, Khademhosseini A. Microfluidic bioprinting of heterogeneous 3D tissue constructs using low-viscosity bioink. Adv Mater. 2016;28(4):677–84.

Liang Q, Gao F, Zeng Z, Yang J, Wu M, Gao C, Cheng D, Pan H, Liu W, Ruan C. Coaxial Scale-Up Printing of Diameter‐Tunable Biohybrid Hydrogel Microtubes with High Strength, Perfusability, and endothelialization. Adv Funct Mater. 2020;30(43):2001485.

Zhou X, Nowicki M, Sun H, Hann SY, Cui H, Esworthy T, Lee JD, Plesniak M, Zhang LG. 3D bioprinting-tunable small-diameter blood vessels with biomimetic biphasic cell layers. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12(41):45904–15.

Dahl SL, Kypson AP, Lawson JH, Blum JL, Strader JT, Li Y, Manson RJ, Tente WE, DiBernardo L, Hensley MT. Readily available tissue-engineered vascular grafts. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(68):68ra69–9.

Gao G, Park JY, Kim BS, Jang J, Cho DW. Coaxial cell printing of freestanding, perfusable, and functional in vitro vascular models for recapitulation of native vascular endothelium pathophysiology. Adv Healthc Mater. 2018;7(23):1801102.

Gao G, Lee JH, Jang J, Lee DH, Kong JS, Kim BS, Choi YJ, Jang WB, Hong YJ, Kwon SM. Tissue engineered bio-blood‐vessels constructed using a tissue‐specific bioink and 3D coaxial cell printing technique: a novel therapy for ischemic disease. Adv Funct Mater. 2017;27(33):1700798.

Gao G, Kim H, Kim BS, Kong JS, Lee JY, Park BW, Chae S, Kim J, Ban K, Jang J. Tissue-engineering of vascular grafts containing endothelium and smooth-muscle using triple-coaxial cell printing. Appl Phys Rev. 2019;6(4):041402.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2021R1F1A1046901). Also, this research was supported by the Korea Medical Device Development Fund grant funded by the Korea government (the Ministry of Science and ICT, the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy, the Ministry of Health & Welfare, the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety) (Project Number: RS-2022-00140622) and the Korean Fund for Regenerative Medicine (KFRM) grant funded by the Korea government (the Ministry of Science and ICT, the Ministry of Health & Welfare). (21A0101L1). Finally, this research was also supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Ministry of Education (2021R1A6A1A03039211).

Funding

Not applicable

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.H. Yang, D. Kang, and S.H. An wrote this article in general. J.Y. Ryu, K.H. Lee, J.S. Kim, M.Y. Song, Y.S. Kim, and S.M. Kwon searched for references and collected information. W.K. Jung, W. Jeong and H. Jeon reviewed and approved the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable as no patient or animals involved.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, G.H., Kang, D., An, S. et al. Advances in the development of tubular structures using extrusion-based 3D cell-printing technology for vascular tissue regenerative applications. Biomater Res 26, 73 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40824-022-00321-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40824-022-00321-2