Abstract

Background

The majority of small bowel obstructions (SBO) are caused by adhesion due to abdominal surgery. Internal hernias, a very rare cause of SBO, can arise from exposed blood vessels and nerves during pelvic lymphadenectomy (PL). In this report, we present two cases of SBO following laparoscopic and robot-assisted lateral lymph node dissection (LLND) for rectal cancer, one case each, of which obstructions were attributed to the exposure of blood vessels and nerves during the procedures.

Case presentation

Case 1: A 68-year-old man underwent laparoscopic perineal rectal amputation and LLND for rectal cancer. Four years and three months after surgery, he visited to the emergency room with a chief complaint of left groin pain. Computed tomography (CT) revealed a closed-loop in the left pelvic cavity. We performed an open surgery to find that the small intestine was fitted into the gap between the left obturator nerve and the left pelvic wall, which was exposed by LLND. The intestine was not resected because coloration and peristalsis of the intestine improved after the hernia was released. The obturator nerve was preserved. Case 2: A 57-year-old man underwent a robot-assisted rectal amputation with LLND for rectal cancer. Eight months after surgery, he presented to the emergency room with a complaint of abdominal pain. CT revealed a closed-loop in the right pelvic cavity, and he underwent a laparoscopic surgery with a diagnosis of strangulated SBO. The small intestine was strangulated by an internal hernia caused by the right umbilical arterial cord, which was exposed by LLND. The incarcerated small intestine was released from the gap between the umbilical arterial cord and the pelvic wall. No bowel resection was performed. The umbilical arterial cord causing the internal hernia was resected.

Conclusion

Although strangulated SBO due to an exposed intestinal cord after PL has been a rare condition to date, it is crucial for surgeons to keep this condition in mind.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The majority of small bowel obstructions (SBO) are caused by adhesion due to abdominal surgery. Internal hernias, a very rare cause of SBO, can arise from exposed blood vessels and nerves during pelvic lymphadenectomy (PL). In this report, we present one case each of strangulated bowel obstruction caused by herniation of obturator nerve after laparoscopic lateral lymph node dissection (LLND) for rectal cancer and by herniation of the umbilical arterial cord after robot-assisted LLND, with a review of the literature.

Case presentation

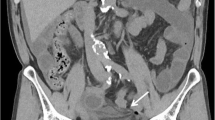

Case1: A 68-year-old man visited our emergency room for the complaint of subacute left groin pain, which gradually worsened. Four years four months prior, he had undergone a laparoscopic abdominoperineal rectal amputation with LLND for rectal cancer. The LLND was a prophylactic dissection that spared the autonomic nervous system and the internal iliac vasculature (upper and lower bladder vessels). Seprafilm was placed postoperatively in the pelvis and just below the midline wound as an anti-adhesive. After surgery, he received standard systemic adjuvant chemotherapy. No recurrent sign was observed. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) images revealed that SBO with a closed-loop had occurred in the left pelvic cavity (Fig. 1). Although the edema of the mesentery was mild and there appeared to be a mild contrast effect on the small bowel wall, there was a possibility of intestinal congestion. He had no abdominal pain, and he had tenderness pain in his left groin and medial part of the thigh. The pain was more pronounced in the left medial thigh than in the abdominal symptom, which was atypical for a strangulated bowel obstruction. However, the patient's symptoms did not improve, and strangulated bowel obstruction was suspected from the imaging findings.

Therefore, we performed emergent open surgery and found the strangulated small bowel with bloody ascites in the left pelvis. The small bowel did not adhere to itself and to the abdominal wall. Approximately 30 cm of the small intestine, located 60 cm proximal to the terminal ileum, was found to be herniated into the gap between the left obturator nerve and the retroperitoneum left pelvic side wall, exhibiting signs of ischemic discoloration. We easily released the incarcerated loop from the hernial orifice. As the color and peristalsis of the ileum improved, intestinal resection was not performed (Fig. 2). On the other hand, there was no tissue available to close the gap caused by the exposed left obturator nerve. Considering the risk of postoperative motor dysfunction if excised, no measures were taken to prevent herniation. He was discharged with no important complication on the 12th postoperative day.

Case2: A 57-year-old man visited our emergency room because of sudden onset of abdominal pain and vomiting. Eight months prior, he had undergone a robot-assisted rectal amputation with LLND following neoadjuvant chemotherapy for rectal cancer. The LLND was the same technique as in case 1. No anti-adhesion material was used. He subsequently received adjuvant chemotherapy with FOLFOX. No recurrent sign was observed. Contrast-enhanced CT images revealed that SBO with a closed-loop had occurred in the right pelvic cavity (Fig. 3). There was edema in the mesentery and a small amount of ascites, but intestinal blood flow was maintained. Contrast-enhanced CT did not show any clear ischemic findings in the intestine; and whereas there was tenderness in the upper abdomen, there were no notable findings in the lower abdomen. Therefore, the patient was admitted for observational management. The next day follow-up CT showed same findings as yesterday, however abdominal bloating was worsening. The patient was considered to have strangulated bowel obstruction caused by exposed vessels and nerves in the pelvis after LLND as in case 1.Therefore, we performed emergent laparoscopic surgery. The operation was started with 3 ports, but the dilated intestine could not be completely eliminated, and it was difficult to secure the operative field, so 4 ports operation was performed. We found the strangulated small bowel in the right pelvic with a band. Although congestion was observed in the strangulated small intestine, there were no signs suggesting necrosis based on its coloration. We released the strangulated small bowel by gentle manipulation. Results showed a band in the right pelvic region, which caused the internal hernia orifice of the strangulated small bowel. It became clear that the band constricting the internal hernia orifice was the right umbilical artery cord (Fig. 4). The venous congestion improved, and peristaltic movements in the strangulated intestine were immediately observed. Therefore, it was deemed feasible to preserve the intestine, and its resection was not performed. We resected the right umbilical artery cord to prevent further re-herniation. The patient progressed favorably after the operation. He was discharged with no major complication on the 7th postoperative day.

Laparoscopic finding in case 2. Left: small bowel herniating into the space after lateral lymph node dissection. Right: the hernial orifice created the umbilical artery cord (Umb). IIA: internal iliac artery, IPA: internal pudendal artery, IVA, inferior vesical artery, ON: obturator nerve, OA: obturator artery

Discussion

We experienced two cases of strangulated SBO after LLND in laparoscopic and robot-assisted surgery for rectal cancer. In both cases, emergent operations were necessary. The band in the first case was the left obturator nerve, whereas the other was the right umbilical cord. The two cases both had a closed-loop in the pelvic cavity, but with different symptoms. It was difficult to speculate on the cause of the SBO. Especially in the first case, the patient presented with atypical symptoms for a SBO, including severe pain in the left thigh without abdominal pain. Symptoms of the first case were thought to have a background of Howship–Romberg sign (HR sign). If we had had experience with cases of internal hernias after LLND, we might have been able to keep this possibility of internal hernias in mind and could have accurately assumed the pathogenesis of the hernia preoperatively.

The most common cause of SBO is surgical adhesions. Internal hernias account for approximately 0.5–5.8% of all cases of intestinal obstruction. More than 90% of all internal hernias are caused by natural or artificial orifices built by the intestine [1]. Internal hernias are an uncommon cause of an SBO, but it is more uncommon that an exposed blood vessel and nerve after pelvic lymphadenectomy (PL) form an internal hernia and cause of an SBO.

PL including LLND is one of the standard procedures performed for several malignant diseases, such as ovarian, cervical, endometrial, prostate, bladder, and rectal cancers [2,3,4,5,6,7]. We searched the PubMed database using the key words “internal hernia”, “pelvic lymphadenectomy (or lymph node dissection)” between 1978 and 2022. 21 cases have been described in 18 reports, including ours (Table 1) [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. Strangulated internal hernia involving the right common iliac artery after PL in a patient with testicular cancer was first reported in 1978 [8]. No report for 30 years thereafter described strangulated internal hernia related to skeletonized vessels or nerves after PL. In 2008, Kim et al. reported strangulated internal hernia involving the right external iliac artery in a patient with cervical cancer [9]. Since then, case reports of PL-related strangulated SBO are increasing in recent years. Ten cases were reported in gynecology, six in urology, and three in gastrointestinal surgery. In previous reports, the external iliac artery and common iliac artery were the most common causes of SBO. In general, PL in gynecology and urogynecology involves an intensive dissection for the lymph nodes whole around the common iliac artery and external iliac artery [2, 3, 5]. On the other hand, these lymph node dissections can be omitted in rectal cancer [7]. Therefore, there are few reports in rectal cancer.

SBO caused by adhesions is significantly less common with laparoscopic surgery [25]. However, in our cases, the laparoscopic and robot-assisted surgery may have reduced adhesions and preserved the mobility of the intestinal tract, which may have facilitated the small intestine to fit into the gap formed by the nerves and blood vessels exposed by the lymph node dissection. Nine of ten cases previously reported in gynecology were postoperative laparoscopic cases. Except for the first report, in urology, five cases were performed laparoscopically or robot-assisted surgery. This may be due to the fact that postoperative adhesions are less likely to occur in these cases.

The 2014 JSCCR Guidelines for Treatment of Colorectal Cancer list total mesorectal excision (TME) or mesorectal excision (ME) with LLND as the standard procedure for lower rectal cancer in Japan [26]. In the JCOG0212 study, ME with LLND had a lower local recurrence, especially in the lateral pelvis, compared to ME alone [27]. As for the approach method, the usefulness of laparoscopic or robot-assisted rather than open approaches have been reported [28, 29]. In our hospital, LLND has been performed laparoscopically since 2013 and robot-assisted since 2018, and we experienced two cases of this disease. In previous reports, both cases of rectal cancer were performed laparoscopic or robot-assisted surgery [15, 18]. Although LLND is not standard in Western countries, technical improvements in minimally invasive surgery have resulted in rapid technical standardization of this complicated procedure [30]. Laparoscopic and robot-assisted approaches to LLND for rectal cancer are becoming ordinary, so it is very important to be aware of this disease.

In previous reports, most of the patients complained of abdominal symptoms, but when the obturator nerve forms an internal hernia and caused intestinal obstruction, some patients, including the case 1, complained of inguinal or thigh pain.[18, 24]. Therefore, it is necessary to be very careful when examining the patient with a history of PL.

In both of the two cases, we found characteristic findings in the pelvis on CT. The small intestine strangulated by internal hernia is seen in the pelvis, and the starting point of the intestinal obstruction is located in the lateral pelvic wall in both cases. Similar CT findings have been seen in several previous reports [15, 16, 24]. If a patient with a history of PL presents with symptoms of SBO, physical findings, or HR sign, and we find characteristic CT findings in the pelvis, we need to consider this disease as a SBO formed by an internal hernia with exposed vessels and nerves in the pelvis. As in the second case, there was a case reported in the past in which the diagnosis of internal hernia was not made, and it took a long time before surgery was performed [24]. If we diagnose this disease, the internal hernia is unlikely to be resolved, so we should perform surgery as soon as possible.

Based on our experience with only two cases of SBO due to an internal hernia in the pelvis, we can expect little or no intra-abdominal adhesions in cases of bowel obstruction. Therefore, a more minimally invasive laparoscopic approach should be considered. However, the second case could have been performed laparoscopically, the dilated small intestine obstructed the development of the surgical field, making surgical manipulation difficult in some situations. As a countermeasure, in order to secure the best possible surgical field and to perform the laparoscopic surgery more reliably, if there is no intestinal ischemia and there is time to spare before the surgery, a nasogastric tube or ileus tube should be implanted before the surgery to decompress the intestinal tract and reduce intestinal dilatation.

Prevention of internal hernias at the time of initial surgery is also an important issue, but there is no clear consensus on this issue. Prevention of internal hernia by peritoneal closure at the time of initial surgery or by covering with an artificial material may be considered. However, peritoneal closure may cause pelvic lymph fistula, and artificial covering may cause infection. So far there is no effective internal hernia prophylaxis at the time of initial surgery. Therefore, we believe it is important to keep this disease firmly in mind and to respond promptly and appropriately if a patient with this condition is seen.

Conclusion

It is possible that the laparoscopic/robotic-assisted surgery has made the intestinal tract, which has less adhesions and preserved mobility, easier to fit into the gap formed by the exposed vessels and nerves after PL. Although cases of strangulated SBO due to an exposed intestinal cord after PL are rare, today, with the establishment of minimally invasive surgery, one may encounter this disease so it is important to keep this disease in mind.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- LLND:

-

Lateral lymph node dissection

- SBO:

-

Small bowel obstruction

- PL:

-

Pelvic lymphadenectomy

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- HR sign:

-

Howship–Romberg sign

- TME:

-

Total mesorectal excision

- ME:

-

Mesorectal excision

References

Martin LC, Merkle EM, Thompson WM. Review of internal hernias: radiographic and clinical findings. Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186(3):703–17.

Yoshihara M, Kajiyama H, Tamauchi S, Iyoshi S, Yokoi A, Suzuki S, et al. Prognostic impact of pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy on clinically-apparent stage I primary mucinous epithelial ovarian carcinoma: a multi-institutional study with propensity score-weighted analysis. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2020;50(2):145–51.

Aslan K, Meydanli MM, Oz M, Tohma YA, Haberal A, Ayhan A. The prognostic value of lymph node ratio in stage IIIC cervical cancer patients triaged to primary treatment by radical hysterectomy with systematic pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy. J Gynecol Oncol. 2020;31(1): e1.

Morice P, Castaigne D, Pautier P, Rey A, Haie-Meder C, Leblanc M, et al. Interest of pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy in patients with stage IB and II cervical carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;73(1):106–10.

García-Perdomo HA, Correa-Ochoa JJ, Contreras-García R, Daneshmand S. Effectiveness of extended pelvic lymphadenectomy in the survival of prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cent Eur J Urol. 2018;71(3):262–9.

Li R, Petros FG, Davis JW. Extended pelvic lymph node dissection in bladder cancer. J Endourol. 2018;32(S1):S49-s54.

Atef Y, Koedam TW, van Oostendorp SE, Bonjer HJ, Wijsmuller AR, Tuynman JB. Lateral pelvic lymph node metastases in rectal cancer: a systematic review. World J Surg. 2019;43(12):3198–206.

Guba AM Jr, Lough F, Collins GJ, Feaster M, Rich NM. Iatrogenic internal hernia involving the iliac artery. Ann Surg. 1978;188(1):49–52.

Kim KM, Kim CH, Cho MK. A strangulated internal hernia behind the external iliac artery after a laparoscopic pelvic lymphadenectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2008;18:417–9.

Dumont KA, Wexels JC. Laparoscopic management of a strangulated internal hernia underneath the left external iliac artery. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4(11):1041–3.

Ardelt M, Dittmar Y, Scheuerlein H, Bärthel E, Settmacher U. Post-operative internal hernia through an orifice underneath the right common iliac artery after Dargent’s operation. Hernia. 2014;18(6):907–9.

Pridjian A, Myrick S, Zeltser I. Strangulated internal hernia behind the common iliac artery following pelvic lymph node dissection. Urology. 2015;86(5):e23–4.

Viktorin-Baier P, Randazzo M, Medugno C, John H. Internal hernia underneath an elongated external iliac artery: a complication after extended pelvic lymphadenectomy and robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy. Urol Case Rep. 2016;8:9–11.

Minami H, Nagasaki T, Akiyoshi T, et al. Laparoscopic repair of bowel herniation into the space between the obturator nerve and the umbilical artery after pelvic lymphadenectomy for cervical cancer. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2018;11(4):409–12.

Kitaguchi D, Nishizawa Y, Sasaki T, Tsukada Y, Kondo A, Hasegawa H, et al. A rare complication after laparoscopic lateral lymph node dissection for rectal cancer: two case reports of internal hernia below the superior vesical artery. J Anus Rectum Colon. 2018;2(3):110–4.

Kambiz K, Lepis G, Khoury P. Internal hernia secondary to robotic assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy and extended pelvic lymphadenectomy with skeletonization of the external iliac artery. Urol Case Rep. 2018;21:47–9.

Ninomiya S, Amano S, Ogawa T, Ueda Y, Shiraishi N, Inomata M, et al. Internal hernia beneath the left external iliac artery after robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy with extended pelvic lymph node dissection: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2019;5(1):49.

Uehara H, Yamazaki T, Kameyama H, et al. Internal hernia beneath the obturator nerve after robot-assisted lateral lymph node dissection for rectal cancer: a case report and literature review. Asian J Endos Surg. 2020;13(4):578–81.

Kanno T, Otsuka K, Takahashi T, Somiya S, Ito K, Higashi Y, et al. Strangulated internal hernia beneath the obturator nerve after laparoscopic radical cystectomy with extended pelvic lymph node dissection. Urology. 2020;145:11–2.

Ai W, Liang Z, Li F, Yu H. Internal hernia beneath superior vesical artery after pelvic lymphadenectomy for cervical cancer: a case report and literature review. BMC Surg. 2020;20(1):312.

Frenzel F, Hollaender S, Fries P, Stroeder R, Stroeder J. Jejunal obstruction due to rare internal hernia between skeletonized external iliac artery and vein as late complication of laparoscopic hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy-case report and review of literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;302(5):1075–80.

Zhang Z, Hu G, Ye M, Zhang Y, Tao F. A strangulated internal hernia beneath the left external iliac artery after radical hysterectomy with laparoscopic pelvic lymphadenectomy: a case report and literature review. BMC Surg. 2021;21(1):273.

Hishikawa T, Oura S, Tomita M. Successful surgical intervention of strangulated ileus with a simple cut of the external iliac vein without vein reconstruction. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2021;15(3):846–51.

Ideyama R, Okushi Y, Kawada K, Itatani Y, Mizuno R, Hida K, et al. Strangulated small bowel obstruction caused by isolated obturator nerve and pelvic vessels after pelvic lymphadenectomy in gynecologic surgery: two case reports. Surg Case Rep. 2022;8:104.

Ha GW, Lee MR, Kim HJ. Adhesive small bowel obstruction after laparoscopic and open colorectal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Surg. 2016;212(3):527–36.

Hashiguchi Y, Muro K, Saito Y, et al. Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JSCCR) Guidelines 2019 for treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2020;25(1):1–42.

Fujita S, Mizusawa J, Kanemitsu Y, Colorectal Cancer Study Group of Japan Clinical Oncology Group, et al. Mesorectal excision with or without lateral lymph node dissection for clinical stage II/ III lower rectal cancer (JCOG0212): a multicenter, randomized controlled, noninferiority trial. Ann Surg. 2017;266(2):201–7.

Nagayoshi K, Ueki T, Manabe T, Moriyama T, Yanai K, Oda Y, Tanaka M. Laparoscopic lateral pelvic lymph node dissection is achievable and offers advantages as a minimally invasive surgery over the open approach. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:1938–47.

Yamaguchi T, Kinugasa Y, Shiomi A, Tomioka H, Kagawa H. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic versus open lateral lymph node dissection for advanced lower rectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:721–8.

Nakanishi R, Yamaguchi T, Akiyoshi T, Konishi T, et al. Laparoscopic and robotic lateral lymph node dissection for rectal cancer. Surg Today. 2020;50(3):209–16.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The authors declare that no funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RF wrote the manuscript. MY, TH, SH, and SI performed the operation. RF edited the article. MY supervised the editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from patients for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fujiwara, R., Yano, M., Matsumoto, M. et al. Two cases of strangulated bowel obstruction due to exposed vessel and nerve after laparoscopic and robot-assisted lateral lymph node dissection (LLND) for rectal cancer. surg case rep 10, 85 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-024-01889-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-024-01889-8