Abstract

Background

This study examines the relationship between coping strategies and symptoms of anxiety or depression among Dutch servicemembers deployed to Afghanistan.

Methods

Coping strategies were assessed in 33 battlefield casualties (BCs) and the control group (CTRLs) of 33 uninjured servicemembers from the same combat units using the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire. A factor analysis was performed, and two clusters of coping strategies were derived, namely, adaptive and maladaptive coping. Symptoms of anxiety and depression were evaluated using the depression and anxiety subscales of the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised. Correlations between coping and symptoms of anxiety and between coping and symptoms of depression were calculated, and a logistic regression was performed.

Results

A moderate correlation was observed between maladaptive coping and symptoms of anxiety in the BC group (r = 0.42) and among the CTRLs (r = 0.56). A moderate correlation was observed between maladaptive coping and symptoms of depression in both groups (r = 0.55). The statistical analysis for the total sample (BCs and CTRLs) demonstrated no association between coping and symptoms of anxiety or depression.

Conclusions

A correlation but no association was observed between maladaptive coping and mental health disorders in deployed Dutch servicemembers. Further research should focus on constructing cluster profiles of coping strategies and associating them with mental health outcomes and reintegration into society.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Combat exposure increases the risk of developing mental health disorders [1, 2]. The number of U.S. servicemembers who met the criteria of depression or anxiety disorder increased significantly after Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) and Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) [3, 4]. The follow-up of Dutch servicemembers after Operation Task Force Uruzgan (TFU; 2006–2010) showed an increased risk of mental health disorders with a higher risk for those who operated predominantly off-base [5, 6].

Servicemembers who sustain combat-related injuries must cope with physical impairments and other stressors related to their injuries. Such individuals have a greater risk of developing mental health disorders than do their uninjured peers [7,8,9]. Battlefield casualties (BCs) from Operation TFU showed higher levels of depression and anxiety than those of uninjured servicemembers from the same combat units [10].

In the Dutch army, after repatriation to the Central Military Hospital, the majority of injured personnel are referred to the Military Rehabilitation Center Aardenburg (MRC). Rehabilitation programs focus mainly on enhancing participation in daily life. Improving participation, e.g., work and community reintegration, is more difficult for injured veterans with mental health problems [11, 12]. Veterans who perceive social support and use constructive coping strategies have better mental health outcomes than do veterans who use unconstructive coping strategies [13]. In the rehabilitation programs of the MRC, coping is not assessed.

Physicians practicing in physical medicine and rehabilitation agree that coping is an important factor of the outcome of a rehabilitation program. Survivors of a traumatic event experience a greater threat to one’s life when injured, especially in cases when they have less control over a situation. This diminished control results in higher levels of perceived stress. After sustaining combat-related injuries, servicemembers also have to confront additional stressors. Servicemembers suffer from physical and psychological consequences of their injuries, such as immediate repatriation, pain and lack of control over body functions. Regulation of emotions (coping) caused by these stressors plays an important role in posttraumatic adaptation [14].

The coping strategies individuals use when confronted with stress can affect both short-term and long-term physical and mental functioning. The problem, though, is that many coping strategies, as well as several classifications to categorize these coping strategies, have been described. In general, adaptive coping responses remove or lessen both fear and the danger of a threat and reduce stress levels. Maladaptive responses reduce the level of fear without reducing the danger, which increases stress levels and is associated with symptoms of depression or anxiety [15]. Adaptive coping, as opposed to maladaptive coping, improves outcomes, e.g., in physical health and social functioning [16,17,18].

Since coping is based on multiple factors, it is not plausible to assume that individuals use only a single coping strategy [19]. Managing trauma and its consequences, survivors may use more than one coping strategy. The focus in research is increasingly on coping profiles created by clustering coping strategies with regard to how individuals adapt [15, 20].

The aim of this study is to assess the relationship between clusters of coping strategies and symptoms of depression or anxiety in Dutch BCs from Operation TFU.

Methods

Study population

All Dutch servicemembers who suffered from combat-related injuries during Operation TFU (2006–2010) and underwent rehabilitation at the MRC Aardenburg, Doorn, the Netherlands, were included; none was excluded. Combat-related injury is specified as an injury incurred as a direct result of hostile action in combat or sustained while going to or returning from a combat mission [10]. The BCs were registered in the general digital admission database of the Dutch Ministry of Defense (MOD). The control group (CTRLs) consisted of uninjured servicemembers from the same combat units. The only exclusion criteria for this cohort was having incurred any injury, either combat-related or non-combat-related. The CTRLs were randomly selected by an independent epidemiologist from the section of Social and Behavioral Research of the MOD. They were matched by gender, age and rank during deployment.

All servicemembers were invited by post and email to complete an online questionnaire between December 2013 and July 2014. If necessary, they received two digital reminders and two reminders by telephone.

Measurements

Participant characteristics

The following data were recorded: gender, age, marital status, number of deployments, educational level, and rank during deployment. Rank during deployment was divided into five rank groups: junior enlisted (E1-E4), senior enlisted (E5-E9), warrant officers (WO1-WO2), junior officers (O1-O3), and senior officers (O4-O10). The duration, in days, of the follow-up period after injury was recorded.

A previous study of the same cohort of Dutch servicemembers with combat-related injuries showed that almost all injuries were caused by explosions (47/48). The average number of injuries per servicemember was 5.2, and the majority of these injuries were located at the extremities [21].

Cognitive coping

The Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ) is a multidimensional questionnaire constructed to identify the cognitive coping strategy someone practices after experiencing a negative event. The questionnaire measures nine different coping strategies: positive reappraisal, self-blame, positive refocusing, catastrophizing, putting in perspective, refocus on planning, rumination, acceptance, and blaming others [22]. Positive reappraisal, positive refocusing, perspective-taking, planning and acceptance are examples of adaptive coping. Rumination, catastrophizing and blaming others are examples of maladaptive coping [15, 23]. The coping strategy of self-blame was left out because it could indicate an internal locus of control (behavioral self-blame) with an adaptive effect, or an external locus of control (characterological self-blame) with a maladaptive effect [24]. For the purpose of this research, the CERQ-short questionnaire, a derivative of CERQ consisting of 18 items [25], was used.

Depressive and anxiety symptomatology

To assess mental health problems, the Dutch language version of the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R) was used. SCL-90-R is a widely used self-reporting instrument for assessing psychosocial distress. It includes 90 questions rated on a 5-point scale, with higher scores meaning greater psychological distress. SCL-90-R is divided into nine symptom subscales: anxiety (range 10–50), depression (range 16–80), somatization (range 12–60), hostility (range 6–30), insufficiency (range 9–45), agoraphobia (range 7–35), sensitivity (range 18–90), sleeping disorder (range 3–15), and additional items (range 9–45) [26, 27]. Depressive and anxiety symptomatology was measured using the depression and anxiety subscales of SCL-90-R.

Data analysis

For data analysis, SPSS version 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used.

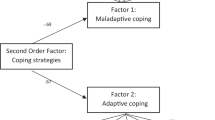

Factor analysis was used to define whether eight coping strategies (positive reappraisal, positive refocusing, putting into perspective, acceptance, refocus on planning, rumination, catastrophizing, and blaming others) could be divided into two groups. A principal component analysis was performed, followed by an orthogonal (varimax) rotation. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were used to assess if the data were suited for factor analysis. Due to the small sample size, no cut-off point was used for factor loading. The coping strategies were classified in one of the two groups based upon the highest factor loading. For each group, it was determined if coping strategies clustered in that group fit either the adaptive or maladaptive coping profile. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was performed to determine the normality of the distribution of scores.

Correlations between symptoms of anxiety or depression and the two groups of coping strategies were analyzed. The following limits were applied to interpret the strength of the association: r = 0–0.19 was regarded as very weak, 0.20–0.39 as weak, 0.40–0.59 as moderate, 0.60–0.79 as strong, and 0.80–1 as very strong correlation [28].

If the distribution of data was normal, a regression analysis was conducted; otherwise, a logistic regression analysis was performed to establish the association between coping as an independent variable, and symptoms of anxiety and depression as dependent variables. A linear relation between the variables is a prerequisite for logistic regression analyses. If no linearity was observed, coping and maladaptive coping were divided into quartiles. Rank and the number of deployments were added as confounders. The variable “sustaining injury” was used twice as an interaction term by multiplying it by adaptive and maladaptive coping. The interaction terms were added to assess whether there was effect modification [29].

Ethical approval

The MOD, the Institutional Review Board and the Medical Ethics Committee of Leiden University, the Netherlands have approved this study (p11.184).

Results

Fifty-eight servicemembers went through a rehabilitation program at the MRC, and 33 (57%) participated in the study. The mean follow-up period after incidence of BCs was 1925 days (interquartile range: 1349-2825). The demographics are summarized in Table 1.

To assess if coping strategies could be divided into two groups, a principal component analysis with an orthogonal rotation was performed, dividing the sample into two groups based on the highest factor loading (Table 2).

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sample adequacy was 0.77, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (P = 0.00). The items clustering together on the same factor confirmed that one factor represented adaptive coping, and the other represented maladaptive coping. The coping strategies of positive reappraisal, positive refocusing, putting into perspective, acceptance, and refocus on planning corresponded to adaptive coping. The coping strategies of rumination, catastrophizing and blaming others corresponded to maladaptive coping. Cronbach’s alpha for adaptive coping was 0.82. Cronbach’s alpha for maladaptive coping was 0.58. Removing an item did not improve the overall reliability of the scale.

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test showed that the distribution of data was not normal. The correlations measured using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient between maladaptive and adaptive coping, and anxiety and depression are shown in Table 3.

Since the data were not normally distributed, the scores of anxiety and depression were dichotomized such that a logistic regression analysis could be performed. Median scores were chosen for the cut-off point: for anxiety, 1.09 was chosen, and for depression, 1.12 was chosen. No linearity was observed between coping and symptoms of anxiety or depression; therefore, maladaptive coping and adaptive coping were divided into quartiles. The logistic regression analysis is shown in Table 4.

The unadjusted model shows no association between adaptive coping and symptoms of anxiety or depression, and maladaptive coping and symptoms of anxiety or depression. Adding two confounders − rank and the number of deployments − affected the highest scores for adaptive coping in relation to anxiety. The confounders also affected the highest score for adaptive coping, and the middle scores for maladaptive coping in relation to depression. However, in the adjusted model, there is no association between coping and symptoms of anxiety, or coping and symptoms of depression (all P values were > 0.05) for the total sample (BCs and CTRLs).

Discussion

A moderate correlation was observed between maladaptive coping and symptoms of anxiety and between maladaptive coping and symptoms of depression in BCs and in CTRLs. No association was observed between coping and symptoms of anxiety or depression.

Doron et al. adopted 3 clusters of coping strategies in the general population: adaptive, avoidant and low [23]. Smith et al. derived 4 ways of coping: individuals practicing active coping strategies, individuals practicing passive coping strategies, individuals practicing low coping strategies and individuals practicing self-blame [30]. The researchers suggested that individuals practicing active coping strategies showed adaptive coping skills, and individuals practicing passive coping strategies showed maladaptive coping skills. Compared to the studies of Doron et al. and Smith et al., individuals practicing low coping strategies showed low levels of coping strategies in general. Individuals practicing active coping strategies showed higher levels of positive reappraisal, positive refocusing, and putting into perspective, while individuals practicing avoidant coping strategies showed higher levels of self-blame, rumination, catastrophizing, and blaming others [23]. Individuals practicing adaptive coping strategies displayed lower levels of depression and anxiety than did individuals practicing avoidant or maladaptive coping strategies [23, 30].

There can be several reasons for the lack of an association between coping and symptoms of anxiety or depression, including a low sample size resulting in a low variability or low scores of depression and anxiety with a small spread of data. More importantly, the data had to be processed to perform a regression analysis. In an already low sample size, coping strategies had to be divided into quartiles, and scores of anxiety and depression had to be dichotomized. Dichotomization can result in a loss of effect size and statistical significance [31]. Studies with a larger sample size are required to assess if an association can be demonstrated.

Another reason for the lack of an association between coping and symptoms of anxiety or depression can be due to Cronbach’s alpha of 0.58 for maladaptive coping. This is a relatively low score according to current views; however, it is acceptable for lack of better options. The low Cronbach’s alpha can be due to several reasons: a low number of questions, or poor interrelatedness between items (due to excessive heterogeneity in the constructs) [32]. Only two questions represent one coping strategy, so the small number of questions could be one of the reasons for a low Cronbach’s alpha. The alternatives would be to use the full-scale CERQ consisting of 36 items instead of 18 items, or to construct more coping profiles (e.g., adaptive, maladaptive, and individuals practicing low coping strategies).

The low scores of anxiety and depression in BCs are remarkable. Many symptoms of depression and anxiety overlap with the symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Eekhout et al. reported that 9% of 1007 Dutch servicemembers had delayed onset of symptoms of PTSD 5 years after OEF with lower ranks (junior enlisted) being at greater risk. The level of deployment stressors was a moderator; a higher level of deployment stressors was related to a greater increase in symptoms of PTSD [5]. Explanations could be that different questionnaires were used (the self-rating inventory for posttraumatic stress disorder vs. the SCL-90-R depression and anxiety scales), or the injured servicemembers in our study might have received treatment for mental health problems during the interim years.

Before OIF and OEF, fewer diagnostic tests were done to explore mental health problems, but other longer follow-up studies of previous wars showed that rank- and combat-related injuries were associated with mental health problems [33]. Low scores of anxiety and depression in our study could be due to underreporting of mental health symptoms. Several factors can impede reporting mental health problems: the stigma associated with admitting mental health problems vs. a medical problem, lack of perceived need for treatment, lack of trust in mental health professionals, treatment beliefs, and the perceived inconvenience of undergoing additional evaluation [34, 35]. Our study was confidential and anonymized but not completely anonymous. Our questionnaires asked if the subjects preferred personal contact in case of mental health problems. None of the participants exercised this option, but it could have influenced their answers, since they could contact caregivers.

Since OIF and OEF, more attention has been paid to mental health problems. The importance of enhancing psychological resilience to withstand mental health problems has been emphasized. The definition adopted by the U.S. military health care providers is “resilience is the capacity to adapt successfully in the presence of risk and adversity.” The factors that promote resilience are divided into individual-level factors including positive coping, family-level factors, unit-level factors, and community-level factors [36]. Not all factors had strong evidence of contributing to resilience; however, this phenomenon implies that further research should concentrate on not only coping but also other factors.

To assess the result of the effectiveness of a program to develop coping skills, outcome measures can be mental health-related (mood or anxiety disorders) but could also be stated in terms of functioning. This possibility suggests evaluating coping in terms of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model that is used as a framework in rehabilitation medicine practice, research and education. Rehabilitation programs aim to enhance and restore functional ability and quality of life to those with physical impairments or disabilities. The ICF framework describes functioning as being a complex interaction of a person’s health condition, environmental factors and personal factors. Although the component ‘personal factors’ has not yet been classified, it includes psychological resources that influence how disability is experienced by the individual. Coping can be considered as a personal factor and evaluated in terms of measuring the level of participation of servicemembers with different coping skills. Consequences of combat-related injury, such as trauma-related pain and lack of control over body functions, can trigger negative thinking and impede rehabilitation. Maladaptive coping can be addressed with education and/or forms of cognitive-behavioral therapy, e.g., cognitive restructuring, and mindfulness [37, 38].

Since OIF and OEF, many studies have been published on mental health in veterans. This study adds the use of cluster analysis to research of coping in this group. For future rehabilitation programs, it is recommended to assess coping strategies and the relationship with symptoms of depression and/or anxiety, as well as the level of participation.

Study limitations

The low sample size was a major limitation; however, the response rate of nearly 60% was acceptable. From the beginning, it was known that the maximum number of BCs that could participate was 58, which affected the choice of our statistical methods. We categorized coping strategies in 2 clusters instead of a larger number, and limited the number of confounders in the logistic regression. This approach might have affected the results, but it is impossible to be certain.

Another limitation was the retrospective design of the study, including the timing of the questionnaires (5 years post-incident).

Conclusions

A moderate correlation was observed between maladaptive coping and mental health disorders in a small sample size of deployed Dutch servicemembers. To better understand mental health problems, more attention should be paid to clusters of coping strategies and the relationships between coping and mental health and between coping and functional outcome.

Abbreviations

- BCs:

-

Battlefield casualties

- CERQ:

-

Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire

- CTRLs:

-

Control group

- ICF:

-

International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health

- MOD:

-

Ministry of Defense

- MRC:

-

Military Rehabilitation Center Aardenburg

- OEF:

-

Operation Enduring Freedom

- OIF:

-

Operation Iraqi Freedom

- PTSD:

-

Posttraumatic stress disorder

- SCL-90-R:

-

Symptom Checklist-90-Revised

- TFU:

-

Task Force Uruzgan

References

Franz MR, Wolf EJ, MacDonald HZ, Marx BP, Proctor SP, Vasterling JJ. Relationships among predeployment risk factors, warzone-threat appraisal, and postdeployment PTSD symptoms. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26(4):498–506.

Buydens-Branchey L, Noumair D, Branchey M. Duration and intensity of combat exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1990;178(9):582–7.

Pickett T, Rothman D, Crawford EF, Brancu M, Fairbank JA, Kudler HS. Mental health among military personnel and veterans. N C Med J. 2015;76(5):299–306.

Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken CS. Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA. 2006;295(9):1023–32.

Eekhout I, Reijnen A, Vermetten E, Geuze E. Post-traumatic stress symptoms 5 years after military deployment to Afghanistan: an observational cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(1):58–64.

Taal EL, Vermetten E, van Schaik DA, Leenstra T. Do soldiers seek more mental health care after deployment? Analysis of mental health consultations in the Netherlands armed forces following deployment to Afghanistan. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2014;5. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v5.23667.

Grieger TA, Cozza SJ, Ursano RJ, Hoge C, Martinez PE, Engel CC, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in battle-injured soldiers. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(10):1777–83.

Koren D, Norman D, Cohen A, Berman J, Klein EM. Increased PTSD risk with combat-related injury: a matched comparison study of injured and uninjured soldiers experiencing the same combat events. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(2):276–82.

Baker DG, Heppner P, Afari N, Nunnink S, Kilmer M, Simmons A, et al. Trauma exposure, branch of service, and physical injury in relation to mental health among U.S. veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. Mil Med. 2009;174(8):773–8.

Hoencamp R, Idenburg FJ, van Dongen TT, de Kruijff LG, Huizinga EP, Plat MC, et al. Long-term impact of battle injuries; five-year follow-up of injured Dutch servicemen in Afghanistan 2006-2010. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0115119.

Sayer NA, Frazier P, Orazem RJ, Murdoch M, Gravely A, Carlson KF, et al. Military to civilian questionnaire: a measure of postdeployment community reintegration difficulty among veterans using Department of Veterans Affairs medical care. J Trauma Stress. 2011;24(6):660–70.

Ladlow P, Phillip R, Etherington J, Coppack R, Bilzon J, McGuigan MP, et al. Functional and mental health status of United Kingdom military amputees postrehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(11):2048–54.

Aflakseir A. The role of social support and coping strategies on mental health of a group of Iranian disabled war veterans. Iran J Psychiatry. 2010;5(3):102–7.

Izard CE, Youngstrom EA, Fine SE, Mostow AJ, Developmental Psychology TCJ. Theory and method. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. 2nd. Edition; 2006. p. 244–92.

Grynberg D, Lopez-Perez B. Facing others' misfortune: personal distress mediates the association between maladaptive emotion regulation and social avoidance. PLoS One. 2018;13(3):e0194248.

Martin RC, Dahlen ER. Cognitive emotion regulation in the prediction of depression, anxiety, stress, and anger. Pers Individ Dif. 2005;39(7):1249–60.

Skinner EA, Edge K, Altman J, Sherwood H. Searching for the structure of coping: a review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(2):216–69.

Lazarus RS. Coping theory and research: past, present, and future. Psychosom Med. 1993;55(3):234–47.

Sideridis GD. Coping is not an ‘either’ ‘or’: the interaction of coping strategies in regulating affect, arousal and performance. Stress Health. 2006;22(5):315–27.

Aldao A, Jazaieri H, Goldin PR, Gross JJ. Adaptive and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies: interactive effects during CBT for social anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2014;28(4):382–9.

de Kruijff LG, Mert A, van der Meer F, Huizinga EP, de Wissel M, van der Wurff P. Dutch military casualties of the war in Afghanistan--quality of life and level of participation after rehabilitation. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2012;155(35):A4233.

Garnefski N, Kraaij V, Spinhoven P. Manual for the use of the cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire. Leiderdorp. The Netherlands: DATEC; 2002.

Doron J, Thomas-Ollivier V, Vachon H, Fortes-Bourbousson M. Relationships between cognitive coping, self-esteem, anxiety and depression: a cluster-analysis approach. Pers Individ Dif. 2013;55(5):515–20.

Janoff-Bulman R. Characterological versus behavioral self-blame: inquiries into depression and rape. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1979;37(10):1798–809.

Garnefski N, Kraaij V. Cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire – development of a short 18-item version (CERQ-short). Pers Individ Dif. 2006;41:1045–53.

Arrindell WA, Ettema JHM. SCL-90. Handbook of a multidimensional psychopathology indicator. Amsterdam: Pearson; 2005.

Arrindell W, Ettema H. Dimensional structure, reliability and validity of the Dutch version of the symptom checklist (SCL-90): data based on a phobic and a “normal” population Ned Tijdschr Psychol 1981;36:77–108.

Swinscow TDV. Statistics at Square One. 9th edition. London (UK). BMJ Publishing Group; 1997. Chapter 11 correlation and regression. Available from: http://www.bmj.com/about-bmj/resources-readers/publications/statistics-square-one/11-correlation-and-regression Accessed 14 Jun 2018.

Field AP. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics. 3rd ed. SAGE Publications Ltd; 2009.

Smith CA, Wallston KA. An analysis of coping profiles and adjustment in persons with rheumatoid arthritis. Anxiety Stress Coping. 1996;9(2):107–22.

MacCallum RC, Zhang S, Preacher KJ, Rucker DD. On the practice of dichotomization of quantitative variables. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(1):19–40.

Tavakol M, Dennick R. Making sense of Cronbach's alpha. Int J Med Educ. 2011;2:53–5.

Ikin JF, Creamer MC, Sim MR, McKenzie DP. Comorbidity of PTSD and depression in Korean war veterans: prevalence, predictors, and impairment. J Affect Disord. 2010;125(1–3):279–86.

Britt TW. The stigma of psychological problems in a work environment: evidence from the screening of service members returning from Bosnia. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2000;30(8):1599–618.

Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Cotting DI, Koffman RL. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(1):13–22.

Meredith LS, Sherbourne CD, Gaillot SJ, Hansell L, Ritschard HV, Parker AM, et al. Promoting Psychological Resilience in the U.S. Military. Rand health quarterly. 2011;1(2):2. Available from: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/monographs/2011/RAND_MG996.pdf Accessed 2 Feb 2018.

Vincent HK, Horodyski M, Vincent KR, Brisbane ST, Sadasivan KK. Psychological distress after orthopedic trauma: prevalence in patients and implications for rehabilitation. PM & R. 2015;7(9):978–89.

Clark ME, Scholten JD, Walker RL, Gironda RJ. Assessment and treatment of pain associated with combat-related polytrauma. Pain Med. 2009;10(3):456–69.

Funding

There was no source of funding.

Availability of data and materials

All relevant data are presented in the text and the tables.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LdK is responsible for the design of the study, acquisition of data, statistical analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting the manuscript. OM is responsible for the design of data analysis and critical revision. MP contributed to the design of the study, statistical analysis and interpretation of data, and critical revision. RH contributed to the design of the study, acquisition of data, and critical revision. PvdW contributed to the design of the study, analysis of data, and critical revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this retrospective observational study was obtained from the Medical Ethics Committee of Leiden University, the Netherlands (p11.184).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest according to the guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

Additional information

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Ministry of Defense, Military Health Care Organization, or the Netherlands’ government.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

de Kruijff, L.G.M., Moussault, O.R.M., Plat, MC.J. et al. Coping strategies of Dutch servicemembers after deployment. Military Med Res 6, 9 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-019-0199-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-019-0199-4