Abstract

This study aimed to analyse the internal structure, internal consistency, and convergent and divergent validity for the Coping Strategies Scale. We found a two-factor solution (maladaptive coping; adaptative coping) with a second-order general factor (coping strategies) that demonstrated adequate factorial structure and internal consistency for a brief nine items instrument in a sample of 211 economically active Brazilians (Mage = 37.07; SD = 13.03). The adaptive strategies factor converged with quality of life and work. It also diverged from phobia, stress, and anxiety. Maladaptive coping strategies converged with phobia, stress, and anxiety and diverged from the quality of work and life. According to the results, we found that coping strategies are a vital personal resource to overcome daily adversity, including those from the current pandemic. The present instrument may impact worldwide, offering conditions to investigate and promote mental health positive outcomes by reinforcing coping assessment during pandemics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Theoretical precursors from coping research defined it as an action-oriented and intrapsychic effort to manage the demands created by stressful events (Lazarus & Folkman, 1991; Taylor & Stanton, 2007; Zeidner & Saklofske, 1996). When individuals use coping daily, they apply their coping strategies (Holahan & Moos, 1987). Coping strategies are essential to an individual’s adaptation during a personal crisis or a stressful event (Heffer & Willoughby, 2017; Labrague et al., 2017; Thompson et al., 2018).

Currently, pandemic periods are traumatic and impact individuals and societal crises with stressful events (Baloran, 2020; Huang et al., 2020). We already have more than 3,535,000 deaths worldwide in the current pandemic generated by SARS-CoV-2 (Worldometers, 2021, May 28). Social, sanitary, and economic problems are affecting individual’s life around the world, and in front of those difficulties, developing mental health, including coping strategies, may be an essential psychological resource to overcome the challenges during this period (Amadasun, 2020; Chatterjee et al., 2020; Gao et al., 2020; Spoorthy et al., 2020).

General mental health indicators such as the presence of adaptative coping strategies may improve individuals’ enduring, resistance, and adaptation during their life (Ivaskevych et al., 2020; Shaw et al., 2020; Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2007), including pandemic context (Faulkner et al., 2020; Guan et al., 2020). On the other hand, maladaptive coping strategies may also appear in front of adversities, for example, (1) anxious behaviours (Daniels & Holtfreter, 2019), (2) escapism and avoidance behaviours (Melodia et al., 2020), (3) rationalisation cognitions (Moral-Jiménez & González-Sáez 2020), and (4) dissociation of their own emotions and cognitions (Guglielmucci et al., 2019). Individuals under extreme pressure may not accommodate contextual demands adequately, resulting in the activation of maladaptive coping strategies. When maladaptive coping is predominant, the individual usually exhibits psychopathological indicators such as stress, anxiety, and phobia (Di Nota et al., 2021; Orgilés et al., 2021; Peres et al., 2021; Shamblaw et al. 2021). Considering these assertions, we proposed the following hypotheses:

H1. There is divergent validity between maladaptive coping strategies and quality of work and life.

H2. There is convergent validity between maladaptive coping strategies and stress, phobia and anxiety.

Mainly, when adaptive coping strategies are developed, individuals usually (1) seek out information to solve problems (Barahmand et al., 2019), (2) create new abilities (Sospeter et al., 2020), (3) develop self-behavioural and emotional control (Ofori et al., 2018), (4) evaluate behavioural alternatives (Lenzen, 2017), and improve their quality of work and life (Du Plessis, 2021; Fathima et al., 2020). Generally, individuals can cope with daily stress and overcome phobias and personal anxieties when adaptive coping is operating (Di Nota et al., 2021; Shamblaw et al. 2021; Orgilés et al., 2021). Considering these assertions, we proposed the following hypotheses:

H3. There is convergent validity between adaptive coping strategies and quality of work and life.

H4. There is divergent validity between adaptive coping strategies and stress, phobia and anxiety.

In the current and post-pandemic context, it is critical to assure that individuals keep their adaptive coping strategies functional and minimise maladaptive coping strategies once stressors and uncertainties occur more frequently, demanding coping strategies to face daily life (Buheji et al., 2020a, b; Zack-Williams, 2020). Different studies showed that, even in stressful contexts, when adaptive coping is predominant, it is possible to obtain good health promotion and mental health fostering conditions for individuals (O'Connor et al., 2018; Ornek et al., 2020; Souza et al., 2021). All those indicators are essential to overcome the current COVID-19 pandemic problems once individuals with appropriate adaptive coping strategies improve their health-promoting self-care and supportive social behaviours (Wong et al., 2020; Kar et al., 2020; Buheji et al., 2020a, b).

Several instruments are available to assess coping in regular and specific contexts (Carver et al., 1989; Garcia et al., 2018; Luca et al., 2020; Pérez-Garín et al., 2020). Furthermore, there is a lack of instruments to assess coping strategies concisely during a pandemic context (Cortez & Antunes, 2022; Cortez et al., 2020). Focusing on coping strategy as an essential resource, we need to generate evidence for coping instruments that can contribute to mental health instrumentation for screening psychological conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic or others that may happen. During COVID-19, Pérez-Fuentes et al. (2021) proposed one instrument for assessing adaptability to change based on the emotional and cognitive dimensions. There are two factors (emotional adaptation and cognitive adaptation) that can be summed as a secondary factor of adaptability to change in their instrument.

We criticise the theoretical foundation of that instrument, considering that the content of the items does not fit with the authors’ interpretation of the internal structure. When we checked the items’ content, it is possible to identify emotional and cognitive content in both factors (Pérez-Fuentes et al., 2021), which may not explain the factorability in two factors. We hypothesised that the difference between the factors fits with coping strategies theorisation (Lazarus & Folkman, 1991; Taylor & Stanton, 2007; Holahan & Moos, 1987; Heffer & Willoughby, 2017; Labrague et al., 2017; Thompson et al., 2018), especially with the concept of adaptive and maladaptive coping (Zeidner & Saklofske, 1996).

The instrument has acceptable quality items content that perfectly fits with adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies, which may be the real explanation for the factorability of the instrument in two factors (Zeidner & Saklofske, 1996), despite the previous interpretation made by the authors (Pérez-Fuentes et al., 2021). As an alternative proposal, we retested their instrument’s factorability, offering coping strategies theorisation as a solid foundation to reinterpret the internal structure in the current study. Based on that perspective, our main objective was to analyse the internal structure, internal consistency, and convergent and divergent validity for the Coping Strategies Scale in a pandemic context.

Method

Participants

We included 211 economically active Brazilians with an average age of 37.07 (SD = 13.03). Most of them were women (72.98%), declared themselves as ‘white’ Latin Americans (74.88%), with higher education (55.50%), worked as technicians in their bachelor area (30.69%) or autonomously and informally (26.51%), 24.10% of the individuals received a health diagnosis associated with the pandemic, and 19.43% had a psychiatric diagnosis with previous pharmacological use. Approximately 24.88% experienced a wage reduction due to the pandemic, 61.61% declared to have adhered to social distancing, 39.81% lived directly with people suffering from the COVID-19 diagnosis, and 30.23% faced grief in the family or close friends due to the pandemic.

Focusing on participants’ self-perception of their mental health, 66.02% of the participants indicated phobia and avoidance of social situations, including their work, to fear becoming ill with COVID-19 during the pandemic. Nearly 38.75% reported feeling highly stressed about daily activities after the beginning of the pandemic. Approximately 36.84% stated that they were highly anxious with losses in their day-to-day duties due to the pandemic. Finally, 27.75% described losses in quality of life due to the pandemic, and 85.09% did not fully adapt to the new living and working conditions resulting from the pandemic.

Instruments

Coping Strategies Scale

A self-report instrument inspired by the Scale of adaptation to change (Peréz-Fuentez et al., 2021). The current Scale is composed of nine items, covering two factors (maladaptive coping — 4 items; adaptive coping — 5 items) that assess how much the individual demonstrates the ability to positive or negative cope with everyday stressful situations related to pandemic. The response scale was a five-point Likert type, ranging from ‘1 = Never’ to ‘5 = Always’. The psychometric properties of the scale are shown in the results of the current study.

Mental Health Self-Perception Questionnaire in Pandemic

A brief self-report questionnaire with four questions was prepared and based on specific literature (APA, 2013; Carver & Connor-Smith, 2010; Elizur & Shye, 1990) to describe the participants’ general mental health conditions. The following signs and symptoms include (a) social phobia, (b) episodic stress, (c) generalised anxiety, and (d) quality of work and life. The response scale consisted in two points (1 = Yes; 2 = No). The participant should mark the presence or absence of the symptom due to the pandemic, associated with impairments in daily life, social interactions, and work. Internal consistency evidence was adequate (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.62; McDonalds’ omega = 0.71).

Sociodemographic and Functional Questionnaire

A brief self-report questionnaire prepared by the researchers in which the participant should indicate (a) age, (b) gender, (c) ethnicity, (d) education, (e) professional nature of the performance, (f) previous mental health diagnosis and use of a psychopharmacological substance, (g) wage reduction in the pandemic, (h) living with people infected in the pandemic, and (j) experience of grief among friends and family due to the pandemic. The response format was open. The participant filled out the information in the corresponding field that we converted into numerical (time) and dichotomic (yes; no) data to describe the participants’ main characteristics.

Procedures

We adapted the instrument from English to Brazilian Portuguese. It followed the procedures described by Van de Vijver (2016), focusing on cultural adaptation and Brazil’s semantic and linguistic aspects. These procedures were (a) independent translation by two translators, (b) content analysis of the items by the Expert Committee to generate the synthesis version of the instrument, and (c) semantic analysis of the instrument by the target population in terms of item comprehensibility. Two cognitive interviews were conducted with the target population, focused on assessing the cognitive process considered throughout the instrument’s response (Nápoles-Springer et al., 2006).

All the procedures above proved to be adequate to individual’s comprehension (Beaton et al., 2000; Hubley & Zumbo, 2011), considering the emergency of proposing screening instruments for future pandemics to create information systems that rapidly respond to health emergencies and social and health crises (Agerfalk et al., 2020). Brazilian Institutional Ethics Committee (CAAE: 36991720.6.0000.5152) approved the project for execution. The recruitment for this research was online, using an unidentified hyperlink sent through the researchers’ social and institutional networks. The interface used to apply the instrument was digital. The average time of participation in the research was about 30 min for each participant.

Data Analysis

Data were analysed using the JASP 0.14.0 software (Love et al., 2019). We characterised the sample according to sociodemographic and functional aspects using descriptive statistics. KMO index (Kaiser Meyer Olkin) and Bartlett’s sphericity test were inspected to apply factor analysis to the data matrix (Hair et al., 2006). We used exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis with simulation of the Mplus DWLS (diagonally weighted least squares) algorithm at JASP (Forero et al., 2009). Factor retention was made with parallel analysis, considering the theoretical indication of adaptive and maladaptive coping (Zeidner & Saklofske, 1996) and previous evidence for the instrument (Peréz-Fuentez et al., 2021). The internal consistency indexes employed were Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega (Dunn et al., 2014). We used Pearson’s correlation to verify the association between instrument factors and other variables to evaluate concurrently relationships in the nomological network of the measured attribute (Barrett et al., 1981).

Results

We tested the prior requisites for the use of factor analysis. We found KMO (Kaiser Meyer Olkin) index = 0.86. The Bartlett test obtained significant results (χ2 = 1210.97; df = 36; p =0.01). Both indicators allowed the use of factor analysis. Exploratory factor analysis indicated one-factor retention with parallel analysis, as shown in Table 1.

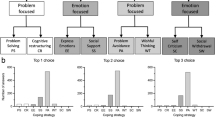

In the use of confirmatory factor analysis, we modelled a restricted model structure with two factors that shown reasonable adjustment (χ2=67.55; df = 33; p=0.01; CFI = 0.98; TLI = 0.97; SRMR = 0.08). We also estimated a second-order factor for the two-factor structure using its factors. The general second-order factor obtained a negative second-order factorial loading with the first factor (λ = −0.698) and a positive second-order factorial loading with the second factor (λ = 0.674). The internal consistency for that second-order factor was adequate (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.879; McDonalds’ omega = 0.888) Fig. 1.

Correlations between coping factors and external variables were suitable. There is a positive correlation between adaptive coping and second-order coping factors (r = 0.827; p<0.01). Also, we found a negative correlation between maladaptive coping and adaptive coping (r = −0.430; p<0.01). The exact negative correlation also occurred between the maladaptive and second-order coping factors (r =−0.864; p<0.01).

Considering relations with other variables, we found adaptive coping presented negative correlation with phobia (r = −0.157; p<0.01), stress (r = −0.365; p<0.01), and anxiety (r = −0.366; p<0.01); and positive correlation with qualify of work and life (r = 0.325; p<0.01). Maladaptive coping presented positive correlation with phobia (r = 0.343; p<0.01), stress (r = 0.663; p<0.01) and anxiety (r = 0.689; p<0.01), and negative correlation with quality of work and life (r = −0.349; p<0.01). We presented all the correlations in Table 2.

Discussion

We analysed the internal structure, internal consistency, and convergent and divergent validity for the Coping Strategies Scale in the pandemic context. There is a robust internal structure considering the evidence generated in the current study. Convergent and divergent validity is also established once coping strategies factors have shown adequacy on correlations between coping factors and other mental health indicators such as stress, phobia, anxiety, and quality of work and life.

The first factor, named maladaptive coping strategies, indicates problematic behavioural, cognitive, and affective patterns that individuals may adopt when dealing with a pandemic context (Moral-Jiménez & González-Sáez, 2020). It includes feeling nervous, anxious, tense, and irritated with disruptive cognitions about the future in the current pandemic scenario (Daniels & Holtfreter, 2019; Guglielmucci et al., 2019). Maladaptive coping strategies usually include non-adaptive emotions and cognition that fit the factor’s content with previous literature indications (Coveney & Olver, 2017).

In the second-order factor, the negative relation of maladaptive coping is also indicated once maladaptive coping strategies lower individuals’ capacities to cope with adversity (Melodia et al., 2020). The negative correlation between maladaptive coping and quality of work and life confirms H1. Also, the positive correlation of maladaptive coping with stress, phobia, and anxiety indicators confirms H2 (Shamblaw et al., 2021; Orgilés et al., 2021).

The second factor, adaptive coping, represents individual cognitive and affective efforts to properly deal with adversity in the current pandemic context (Barahmand et al., 2019). It includes self-monitoring behaviour and emotions when dealing with problems, planning to respond adequately to adversities with self and contextual awareness to gather information, process, and act positively in the current pandemic circumstance (Lenzen, 2017).

Compared with the literature, the content of the adaptive coping factor is appropriate. It includes emotional and cognitive self-regulation, conscientious planning, and the decision to overcome situational and personal adversity (Ofori et al., 2018; Sospeter et al., 2020). The positive correlation between adaptive coping and quality of work and life confirms H3. The negative correlation between stress, phobia, anxiety indicators, and adaptive coping corroborates H4 (Di Nota et al., 2021; Shamblaw et al., 2021).

Considering the second-order factor, the positive relationship with the adaptive coping and negative association with the maladaptive coping showed that the second-order factor theorisation adjusts appropriately in the current internal structure compared to Pérez-Fuentes et al. (2021) previous internal structure. Considering the new evidence generated in the present study, the second-order factor might designate strategies that boost individuals’ capacities to cope with adversity fitting its definitions with core definitions from coping theorisation (Holahan & Moos, 1987; Zeidner & Saklofske, 1996). Focusing on that theorisation, individuals may use it to overcome difficulties to assess coping strategies during pandemics (Cortez et al., 2020).

In a general perspective, the higher the individual’s score on coping strategies, the more adaptive coping will be expressed. Also, lower expressions of maladaptive coping can be expected to improve individual regular life conditions to overcome difficulties in pandemic contexts (Heffer & Willoughby, 2017; Taylor & Stanton, 2007). It is also probable that individuals with higher scores on adaptive coping strategies will demonstrate low behaviours and cognitions associated with phobia, stress, and anxiety (Edraki et al., 2018; Ollendick et al., 2017).

When individuals can use adaptative coping strategies in their daily life, even if it is complex and stressful, psychopathological outcomes are less probable, fostering the importance of coping in the current pandemic context (Compas et al., 2017). Finally, a higher quality of life and work will be experienced for those with higher coping strategies (Fairfax et al., 2019; Luca et al., 2020; Zamanian et al., 2018). It demonstrates that part of our efforts to overcome pandemic issues may integrate adaptive coping development to reintegrate and keep people facing their daily lives and work with personal resources to bypass mental and contextual difficulties that intensified in the current pandemic (Kar et al., 2020).

We highlight the impact of our study; it may impact health promotion worldwide, offering a brief instrumental in reinforcing coping assessment during pandemics. Coping assessment is fundamental to identifying adaptive personal resources that promote protection and empowerment for individuals psychologically, focusing on overcoming current and post-pandemic issues. Our study’s limitation highlights the non-probabilistic and context-restricted sampling that needs to expand sociodemographic characteristics in other countries, considering its populational and cultural specificities. In the current proposal, we evidence the Coping Strategies Scale as a preeminent instrument to assess abilities to cope adaptively and maladaptively in daily life during pandemics, focusing on possible outcomes that may harm or improve individuals’ psychological state and quality of work and life.

Data availability

According to the Brazilian National Committee of Ethical Research and its Ethics Resolutions, our data is available for meta-synthesis by corresponding to the author: Cortez, P.A. (cor.afonso@gmail.com). We do not have the approbation to public upload the data, even though future studies may use our data in aggregate and non identified datasets.

References

Ågerfalk, P. J., Conboy, K., & Myers, M. D. (2020). Information systems in the age of pandemics: COVID-19 and beyond. European Journal of Information System, 29(1), 203–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2020.1771968

Amadasun, S. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic in Africa: What lessons for social work education and practice? International Social Work, 0020872820949620 10.1177%2F0020872820949620.

APA - American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub.

Baloran, E. T. (2020). Knowledge, attitudes, anxiety, and coping strategies of students during COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 25(8), 635–642. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2020.1769300

Barahmand, N., Nakhoda, M., Fahimnia, F., & Nazari, M. (2019). Understanding everyday life information seeking behavior in the context of coping with daily hassles: A grounded theory study of female students. Library & Information Science Research, 41(4), 100980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2019.100980

Barrett, G. V., Phillips, J. S., & Alexander, R. A. (1981). Concurrent and predictive validity designs: A critical reanalysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 66(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.66.1.1

Beaton, D. E., Bombardier, C., Guillemin, F., & Ferraz, M. B. (2000). Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine, 25(24), 3186–3191 https://journals.lww.com/spinejournal/Fulltext/2000/12150/Guidelines_for_the_Process_of_Cross_Cultural.14.aspx

Buheji, M., Ahmed, D., & Jahrami, H. (2020a). Living uncertainty in the new normal. International Journal of Applied Psychology, 10(2), 21–31. https://doi.org/10.5923/j.ijap.20201002.01

Buheji, M., Hassani, A., Ebrahim, A., da Costa Cunha, K., Jahrami, H., Baloshi, M., & Hubail, S. (2020b). Children and coping during COVID-19: A scoping review of bio-psycho-social factors. International Journal of Applied Psychology, 10, 8–15. https://doi.org/10.5923/j.ijap.20201001.02

Carver, C. S., & Connor-Smith, J. (2010). Personality and coping. Annual Review of Psychology, 61(1), 679–704. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100352

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(2), 267–283. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267

Chatterjee, S. S., Malathesh Barikar, C., & Mukherjee, A. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on pre-existing mental health problems. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 102071 10.1016%2Fj.ajp.2020.102071.

Compas, B. E., Jaser, S. S., Bettis, A. H., Watson, K. H., Gruhn, M. A., Dunbar, J. P., Williams, E., & Thigpen, J. C. (2017). Coping, emotion regulation, and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 143(9), 939–991. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000110

Cortez, P. A., & Antunes, M. C. (2022). Medidas de Saúde Mental em Pandemias. Juruá Press.

Cortez, P. A., Joseph, S. J., Das, N., Bhandari, S. S., & Shoib, S. (2020). Tools to measure psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic: What do we have in the platter? Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 53(1), 1–4 10.1016%2Fj.ajp.2020.102371.

Coveney, A., & Olver, M. (2017). Defence mechanism and coping strategy use associated with selfreported eating pathology in a non-clinical sample. Psychreg Journal of Psychology, 1(2), 19–39 https://www.pjp.psychreg.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/18-39.pdf

Daniels, A. Z., & Holtfreter, K. (2019). Moving beyond anger and depression: The effects of anxiety and envy on maladaptive coping. Deviant Behavior, 40(3), 334–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2017.1422457

Dunn, T. J., Baguley, T., & Brunsden, V. (2014). From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. British Journal of Psychology, 105(3), 399–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12046

Du Plessis, M. (2021). Enhancing psychological wellbeing in industry 4.0: The relationship between emotional intelligence, social connectedness, work-life balance and positive coping behaviour. In Agile Coping in the Digital Workplace (pp. 99–118). Springer.

Edraki, M., Rambod, M., & Molazem, Z. (2018). The effect of coping skills training on depression, anxiety, stress, and self-efficacy in adolescents with diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Community Based Nursing and Midwifery, 6(4), 324–333 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6226609/

Elizur, D., & Shye, S. (1990). Quality of work life and its relation to quality of life. Applied Psychology, 39(3), 275–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.1990.tb01054.x

Fathima, F. N., Awor, P., Yen, Y. C., Gnanaselvam, N. A., & Zakham, F. (2020). Challenges and coping strategies faced by female scientists—A multicentric cross sectional study. PloS one, 15(9), e0238635. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238635

Fairfax, A., Brehaut, J., Colman, I., Sikora, L., Kazakova, A., Chakraborty, P., & Potter, B. K. (2019). A systematic review of the association between coping strategies and quality of life among caregivers of children with chronic illness and/or disability. BMC Pediatrics, 19(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-019-1587-3

Faulkner, G., Rhodes, R. E., Vanderloo, L. M., Chulak-Bozer, T., O'Reilly, N., Ferguson, L., & Spence, J. C. (2020). Physical activity as a coping strategy for mental health due to the COVID-19 virus: A potential disconnect among Canadian adults? Frontiers in Communication, 5, 74–81. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2020.571833

Forero, C. G., Maydeu-Olivares, A., & Gallardo-Pujol, D. (2009). Factor analysis with ordinal indicators: A Monte Carlo study comparing DWLS and ULS estimation. Structural Equation Modeling, 16(4), 625–641. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510903203573

Gao, J., Zheng, P., Jia, Y., Chen, H., Mao, Y., Chen, S., Wang, Y., Fu, H., & Dai, J. (2020). Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. Plos one, 15(4), e0231924. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231924

García, F. E., Barraza-Peña, C. G., Wlodarczyk, A., Alvear-Carrasco, M., & Reyes-Reyes, A. (2018). Psychometric properties of the Brief-COPE for the evaluation of coping strategies in the Chilean population. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 31(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41155-018-0102-3

Guan, Y., Deng, H., & Zhou, X. (2020). Understanding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on career development: Insights from cultural psychology. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 119(1), e103438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103438

Guglielmucci, F., Monti, M., Franzoi, I. G., Santoro, G., Granieri, A., Billieux, J., & Schimmenti, A. (2019). Dissociation in problematic gaming: A systematic review. Current Addiction Reports, 6(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-019-0237-z

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. (2006). Multivariate data analysis. Uppersaddle River.

Heffer, T., & Willoughby, T. (2017). A count of coping strategies: A longitudinal study investigating an alternative method to understanding coping and adjustment. PloS one, 12(10), e0186057. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186057

Holahan, C. J., & Moos, R. H. (1987). Personal and contextual determinants of coping strategies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(5), 946–955. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.5.946

Huang, L., Lei, W., Xu, F., Liu, H., & Yu, L. (2020). Emotional responses and coping strategies in nurses and nursing students during Covid-19 outbreak: A comparative study. PLoS One, 15(8), e0237303. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237303

Hubley, A. M., & Zumbo, B. D. (2011). Validity and the consequences of test interpretation and use. Social Indicators Research, 103(2), 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9843-4

Ivaskevych, D., Fedorchuk, S., Borysova, O., Kohut, I., Marynych, V., Petrushevskyi, Y., et al. (2020). Association between competitive anxiety, hardiness, and coping strategies: a study of the national handball team. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 20, 477–483. https://doi.org/10.7752/jpes.2020.s1070

Kar, S. K., Arafat, S. Y., Kabir, R., Sharma, P., & Saxena, S. K. (2020). Coping with mental health challenges during COVID-19. In Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) (pp. 199–213). Springer.

Labrague, L. J., McEnroe-Petitte, D. M., Gloe, D., Thomas, L., Papathanasiou, I. V., & Tsaras, K. (2017). A literature review on stress and coping strategies in nursing students. Journal of Mental Health, 26(5), 471–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2016.1244721

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1991). The concept of coping. In A. Monat & R. S. Lazarus (Eds.), Stress and coping: An anthology (pp. 189–206). Columbia University Press.

Lenzen, S. A., Daniëls, R., van Bokhoven, M. A., van der Weijden, T., & Beurskens, A. (2017). Disentangling self-management goal setting and action planning: A scoping review. PloS one, 12(11), e0188822.

Love, J., Selker, R., Marsman, M., Jamil, T., Dropmann, D., Verhagen, J., Ly, A., Gronau, Q. F., Šmíra, M., Epskamp, S., & Matzke, D. (2019). JASP: Graphical statistical software for common statistical designs. Journal of Statistical Software, 88(2), 1–17.

Luca, L., Noronha, A. P. P., Queluz, F. N. F. R., & Santos, A. A. A. (2020). New validity evidence for the Coping Strategies Inventory. Ciencias Psicologicas, 14(2), e2319. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v14i2.2319

Melodia, F., Canale, N., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). The role of avoidance coping and escape motives in problematic online gaming: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00422-w

Moral-Jiménez, M. D. L. V., & González-Sáez, M. E. (2020). Distorsiones Cognitivas y Estrategias de Afrontamiento en Jóvenes con Dependencia Emocional. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología y Salud, 1(1), 15–30. https://doi.org/10.23923/j.rips.2020.01.032

Nápoles-Springer, A. M., Santoyo-Olsson, J., O'Brien, H., & Stewart, A. L. (2006). Using cognitive interviews to develop surveys in diverse populations. Medical Care, S21–S30 https://www.jstor.org/stable/41219501?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference

Di Nota, P. M., Kasurak, E., Bahji, A., Groll, D., & Anderson, G. S. (2021). Coping among public safety personnel: A systematic review and meta–analysis. Stress and Health, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.3039

O'Connor, C. A., Dyson, J., Cowdell, F., & Watson, R. (2018). Do universal school-based mental health promotion programmes improve the mental health and emotional wellbeing of young people? A literature review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(3-4), e412–e426. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14078

Ofori, P. K., Tod, D., & Lavallee, D. (2018). An exploratory investigation of superstitious behaviours, coping, control strategies, and personal control in Ghanaian and British student-athletes. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 16(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2016.1142460

Orgilés, M., Morales, A., Delvecchio, E., Francisco, R., Mazzeschi, C., Pedro, M., & Espada, J. P. (2021). Coping behaviors and psychological disturbances in youth affected by the COVID-19 health crisis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 845. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.565657

Ollendick, T. H., Ryan, S. M., Capriola-Hall, N. N., Reuterskiöld, L., & Öst, L. G. (2017). The mediating role of changes in harm beliefs and coping efficacy in youth with specific phobias. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 99, 131–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2017.10.007

Ornek, O. K., & Esin, M. N. (2020). Effects of a work-related stress model based mental health promotion program on job stress, stress reactions and coping profiles of women workers: A control groups study. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09769-0

Pérez-Garín, D., Recio, P., Silván-Ferrero, P., Nouvilas, E., & Fuster-Ruiz de Apodaca, M. J. (2020). How to cope with disabilities: Development and psychometric properties of the Coping With Disability Difficulties Scale (CDDS). Rehabilitation Psychology, 65(1), 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1037/rep0000293

Peres, R. S., Frick, L. T., Queluz, F. N. F. R., Fernandes, S. C. S., Priolo, S. R., Stelko-Pereira, A. C., Martins, J. Z., Lessa, J. P. A., Veiga, H. M. D. S., & Cortez, P. A. (2021). Evidências de validade de uma versão brasileira da Fear of COVID-19 Scale. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 26, 3255–3264. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232021268.06092021

Shamblaw, A. L., Rumas, R. L., & Best, M. W. (2021). Coping during the COVID-19 pandemic: Relations with mental health and quality of life. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 62(1), 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000263

Shaw, Y., Bradley, M., Zhang, C., Dominique, A., Michaud, K., McDonald, D., & Simon, T. A. (2020). Development of resilience among rheumatoid arthritis patients: A qualitative study. Arthritis Care & Research, 72(9), 1257–1265. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.24024

Skinner, E. A., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2007). The development of coping. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 119–144. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085705

Sospeter, M., Shavega, T. J., & Mnyanyi, C. (2020). Social emotional model for coping with learning among adolescent secondary school students. Global Journal of Educational Research, 19(2), 179–191 https://www.ajol.info/index.php/gjedr/article/view/202559

Souza, J. B. D., Heidemann, I. T. S. B., Massaroli, A., & Geremia, D. S. (2021). Health promotion in coping with COVID-19: A Virtual Culture Circle experience. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 74, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2020-0602

Spoorthy, M. S., Pratapa, S. K., & Mahant, S. (2020). Mental health problems faced by healthcare workers due to the COVID-19 pandemic–A review. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 102119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102119

Taylor, S. E., & Stanton, A. L. (2007). Coping resources, coping processes, and mental health. Annual Review of Psychology, 3, 377–401. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091520

Thompson, N. J., Fiorillo, D., Rothbaum, B. O., Ressler, K. J., & Michopoulos, V. (2018). Coping strategies as mediators in relation to resilience and posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 225, 153–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.08.049

Van de Vijver, P. J. R. (2016). Test adaptations. In F. T. L. Leong, D. Bartram, F. M. Cheung, K. F. Geisinger, & D. Iliescu (Eds.), The ITC International Handbook of Testing and Assessment (pp. 364–376). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/med:psych/9780199356942.003.0025

Wong, M. C., Teoh, J. Y., Huang, J., & Wong, S. H. (2020). The potential impact of vulnerability and coping capacity on the pandemic control of COVID-19. The Journal of Infection, 81(5), 816–846 10.1016%2Fj.jinf.2020.05.060.

Worldometers. (2021, March 9). Corona virus update – Deaths from COVID-19 virus pandemic. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

Zamanian, H., Poorolajal, J., & Taheri-Kharameh, Z. (2018). Relationship between stress coping strategies, psychological distress, and quality of life among hemodialysis patients. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 54(3), 410–415. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12284

Zack-Williams, A. (2020). Africa–coping with the ‘new normal’. Review of African Political Economy, 47(163), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2020.1794111

Zeidner, M., & Saklofske, D. (1996). Adaptive and maladaptive coping. In M. Zeidner & N. S. Endler (Eds.), Handbook of Coping: Theory, Research, Applications (pp. 505–531). John Wiley & Sons.

Code Availability

We used GUI software. There is no specific coding available. We stated all the procedures in data analysis and may offer the outputs for those that are interested. Contact the correspondence author by email (cor.afonso@gmail.com) to obtain the software output.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Project conceptualization = 1

Literature search and refining idea = 2

Study design and application = 3

Data analysis = 4

Manuscript contribution = 5

Manuscript revision = 6

Pedro Afonso Cortez = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

Heila Magali da Silva Veiga = 1, 2, 3, 5, 6

Ana Carina Stelko-Pereira = 1, 2, 3, 5

João Paulo Araújo Lessa = 1, 2, 3, 5

Jucimara Zacarias Martins = 1, 2, 3, 5

Sheyla Christine Santos Fernandes = 1, 2, 3, 5

Sidnei Rinaldo Priolo Filho = 1, 2, 3, 5

Francine Náthalie Ferraresi Rodrigues Queluz = = 1, 2, 3, 5

Loriane Trombini Frick = 1, 2, 3, 5

Rodrigo Sanches Peres = 1, 2, 3, 5

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Registered and approved by the Brazilian National Committee of Ethical Research (ID: 37798820.8.0000.5508 - you may use the public checking tool https://plataformabrasil.saude.gov.br/ - only available in Brazilian Portuguese).

Consent to Participate

According to the Brazilian National Committee of Ethical Research and its Ethics Resolutions, we state protocol ID 37798820.8.0000.5508 obtained consent from participants. It also clarified the study’s objectives, risks, and benefits to the research participants before applying the survey protocol for those who informed previous voluntary consent.

Consent for Publication

According to the Brazilian National Committee of Ethical Research and its Ethics Resolutions, we state the protocol ID 37798820.8.0000.5508 obtained consent for publication of participants data non identified.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Cortez, P.A., da Silva Veiga, H.M., Stelko-Pereira, A.C. et al. Brief Assessment of Adaptive and Maladaptive Coping Strategies During Pandemic. Trends in Psychol. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43076-023-00274-y

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43076-023-00274-y