Abstract

Human emotion recognition remains a challenging and prominent issue, situated at the convergence of diverse fields, such as brain–computer interfaces, neuroscience, and psychology. This study utilizes an EEG data set for investigating human emotion, presenting novel findings and a refined approach for EEG-based emotion detection. Tsallis entropy features, computed for q values of 2, 3, and 4, are extracted from signal bands, including theta-θ (4–7 Hz), alpha-α (8–15 Hz), beta-β (16–31 Hz), gamma-γ (32–55 Hz), and the overall frequency range (0–75 Hz). These Tsallis entropy features are employed to train and test a KNN classifier, aiming for accurate identification of two emotional states: positive and negative. In this study, the best average accuracy of 79% and an F-score of 0.81 were achieved in the gamma frequency range for the Tsallis parameter q = 3. In addition, the highest accuracy and F-score of 84% and 0.87 were observed. Notably, superior performance was noted in the anterior and left hemispheres compared to the posterior and right hemispheres in the context of emotion studies. The findings show that the proposed method exhibits enhanced performance, making it a highly competitive alternative to existing techniques. Furthermore, we identify and discuss the shortcomings of the proposed approach, offering valuable insights into potential avenues for improvements.

Highlights

-

Subject independent human emotion identification is studied using SEED data set.

-

Tsallis entropy is employed as feature and performance variation with Tsallis parameter (q = 2, 3, 4) is examined.

-

Performance of kNN classifier is examined with Tsallis entropy feature.

-

Emotion identification at various levels is studied, brain region, EEG rhythms, brain hemisphere.

-

Prospects of TsEn-based real-time emotion recognition framework is canvassed.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

1.1 Emotions and emotions recognition

The human brain is one of the most evolved brains among all other living organisms. Emotions result from cognitive mechanisms within billions of neurons subjected to situations and surroundings [1]. With the advancement of science and technology, the practice to explore and quantify the subjective emotions of human beings has gained little success but gaining higher accuracy remains challenging. The perception, situational reaction, and critical thinking biased with human emotions have been tedious to generalize or functionalize. However, a deeper and more accurate understanding of human emotion would essentially push forward the mental health care disciplines and next-generation artificial intelligence.

As a primitive categorization, human emotions were classified based on two major models, namely discrete emotion models, which rank emotions into happiness, sadness, anger, fear, and disgust [2]. The second model gives a preliminary qualification based on the emotion’s arousal and valance [3]. The model is called the bidimensional emotion model, which categorizes emotions in a two-dimensional plane within the four quadrants. The intensity of a particular emotion is quantified as its valance. The x-axis of the plane describes the valance of emotions. Distributions towards the left of the origin shows negativeness while towards the right indicates positiveness.

Similarly, the arousal axis grades the activation and calmness of the emotion from top to bottom. Systematic and scientific emotion detection is inevitable for generalizing and categorizing emotion and extending it to multidisciplinary science and technology development. This study is conducted on the SEED data set which is based on the discrete emotion model. However, these enormous data inevitably require an efficient classification to make reliable conclusions.

1.2 Why EEG?

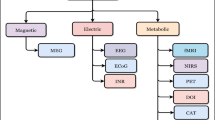

Technology has significantly evolved to detect human emotions through various methods. Signals from speech, physical posture, body language, and facial expressions are a few of them [4,5,6]. A more precise and clinical detection mechanism of human emotion has been established by Hans Berger et al. using electroencephalography (EEG) [7]. EEG involves the direct measurement of electric signals and their variations during brain activity that helps to digitalize subjective human emotions in the best way possible. The preference for EEG recordings over different alternatives is also substantiated by the fact that primary impulse in response to any input is generated in the brain. This impulse then subsequently transmits through the central nervous system to the rest of the peripheral systems. From this context, EEG recordings give the source's emotional response, whereas other physiological factors might be seen as a by-product of the brain’s response to the stimulus [8]. Thus, a substantial rise in the number of studies that employed EEG time series to build an emotion identification framework can be seen recently.

1.3 Entropy-based emotion recognition

In the initial days of the EEG-based research, the EEG recordings were analyzed using linear methods, particularly in the frequency zone. However, it would be incorrect to characterize brain activity as linear. Neurons connect diversely and nonlinearly at all levels, cellular or global. Therefore, use of linear techniques alone will not provide a comprehensive account of brain’s electrical responses. Given this information, nonlinear algorithms have been employed further to unravel underlying information that remains undiscovered with classic linear approaches. Nonlinear approaches have consistently outscored the findings of linear algorithms in studying mental activities, including emotion identifications [9,10,11].

Entropy measures are being broadly used to build emotion recognition frameworks among the several nonlinear approaches found in the literature. Entropy, which describes the nonlinear properties of a nonstationary system, is the rate of information that a time series report. As a result, entropy measures are valuable tools for evaluating the chaotic dynamics of nonstationary systems like the brain. Several research studies have used these nonlinear approaches to extract emotional states from EEG records [12,13,14].

The concept of entropy first came in the field of thermodynamics. Further, it was adapted and redefined in the information theory by Shannon and known as Shannon’s entropy. Shannon entropy in signal analysis defines the amount of information a signal provides, indicating its complexity, irregularity, or unpredictability [15]. Later many entropy generalizations were formulated and effectively employed for various EEG-based medical research, including mental illnesses, epilepsy [16,17,18], Alzheimer’s [19,20,21], autism, and depression [22, 23], among others. Considering these outcomes, entropy measures were employed in studying emotion recognition from EEG signals [24,25,26,27].

1.4 Previous entropy-based emotion studies

Literature shows that various entropy functions have been derived and used for emotion recognition with the EEG data set [13]. Table 1 summarises all the entropy works and our results from Tsallis entropy for emotion recognition. For simplification, all the entropies studied to date can be categorized as (i) regularity-based entropy (ii) Predictability-based or symbolic entropy, and the (iii) multiscale entropy.

Regularity in the EEG context is defined as the rate of the repetitiveness of specific patterns in the signal. Some of the widely used regularity-based entropy are approximate entropy and sample entropy. This entropy works on the probability of having repetitive patterns within the length of the signals selected. Studies using approximate and sample entropy gave accuracy between 73% and 90%.

Predictability defines the stability and the deterministic evolution of the nonstationary systems in time. Some of the entropies in this category are Shannon entropy (ShEn) and its generalization Renyi and Tsallis entropy and another variant of ShEn differential entropy. These entropy matrices are based on the probability distribution of the amplitude of the signal. Permutation entropy is also an example of it. Literature shows that the accuracies obtained from these matrices are between 65% and 82% [28,29,30,31,32].

Considering the multiscale nature of the EEG data set, multiscale entropy has been introduced. Multiscale entropy is computed by decomposing the signal into coarse-grained time series scales. It comprises of all the entropy stated above calculated in multi scales. Recognition accuracies from multiscale entropy matrices range between 73% and 94% [33,34,35,36,37].

1.5 Feature Selection: Why Tsallis entropy?

The previous section discussed various entropy measures used in emotion recognition. Yet among several others, Tsallis entropy, a very potential generalized form of Shannon’s entropy remains unexplored in EEG-based emotion recognition. Tsallis entropy (TsEn) [38, 39] explores the nonextensive statistics of a system. It successfully describes systems having either multifractal space–time constraints, long-range interactions, or long-term memory effects [40]. Tsallis entropy incorporates a nonextensive parameter ‘q’ which acts as a zoom lens to study all systems varying from short- to long-range interactions.

1.6 Mathematical formulation

Since 1948, Shannon’s entropy has been the fundamental and most widely used entropy to evaluate system complexity. Mathematically, Shannon’s Entropy is [15]

where N is the microscopic configuration of the system and \({P}_{i}\) is the probability of occurrence of the \(i\) th configuration, and the sum of the probabilities should be unity, i.e., \(\sum_{i}{P}_{i }=1\).

Limitation: Shannon’s entropy is valid for systems with short-range interaction and fails to comprehend systems with long-range interaction.

\({E}_{Sh}\) is additive, \({E}_{Sh}\left(X\cup Y\right)= {E}_{Sh}\left(X\right)\) + \({E}_{Sh}\left(Y\right)\) Meaning systems X and Y are independent.

To overcome this limitation, a non-additive statistic was proposed [38, 39] by Tsallis therefore named Tsallis entropy. It is formulated as

When \(q\to 1\), \({E}_{ts}\) reduces to the definition of \({E}_{Sh}\) as:

As \({E}_{ts}\) follows nonextensive statistics and it undertakes the rule of pseudo additivity as

In Eqs. (2) and (3), q is a parameter that measures the degree of non-extensivity [40]. A value of q = 1 corresponds to extensivity, that is, Shannon’s entropy. On the other hand, q < 1 corresponds to super-extensive, \({[E}_{ts}\left(X\cup Y\right)>{E}_{ts}\left(X\right)+ {E}_{ts}\left(Y\right)\) and q > 1 corresponds to subextensive [\({E}_{ts}\left(X\cup Y\right)<{E}_{ts}\left(X\right)+ {E}_{ts}\left(Y\right)\)] statistics.

As explained, Tsallis’ work presents a generalized form of Shannon’s entropy which can effectively describe systems or phenomena with long-range interaction. Primary electrical responses are generated from the cortical neurons [41]. After reaching a threshold value, these activation potential travels and reaches the brain scalp and is the recorded as EEG with respect to time and space. Therefore, EEG comes with inherent nonextensivity because of the long-range correlation that exists among billions of neurons [42]. These long rage interactions are the electrical information which are transmitted across different cortical areas and feedback loops composed of corticothalamic and thalamocortical networks [43]. Above argument suggests it is theoretically reasonable to replace existing entropy measures with Tsallis entropy to get a grip on the long-range effects of EEG. It is also sensible to consider EEG as a subextensive system (i.e., q > 1), since mutual information exists among different neuron clusters [44, 45].

1.7 Research questions

As far as we know, this study is the first to propose Tsallis entropy as a feature (extracted from EEG) to study cross-subject emotions using SEED data sets. The present article explores the answers to the following queries:

-

Are Tsallis entropy-based features reliable when attempting to extract complex information from EEG data sets to classify emotions?

-

Does the classification performance depend on the entropic index “q,” also called the Tsallis parameter?

-

Is Tsallis entropy as reliable for obtaining information from EEG data sets as Shannon entropy or other entropy indices? The study assesses the robustness of the feature vectors retrieved in terms of ‘accuracy’ and ‘F1 score’ performance metrices.

It also investigates the number of effective EEG electrodes, appropriate brain region, and advisable frequency range that could be preferred to study emotion identification in the future.

2 Materials and methods

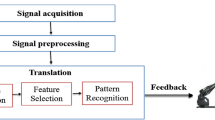

The methodology diagram in Fig. 1 illustrates the essential phases of the research proposed. It consists of 4 steps each of which is explained in further subsections.

2.1 Experimental data

We analyzed the publicly accessible data set SEED (SJTU emotion EEG data set) [46]. The SEED data set comprises of 62-channel EEG data which are collected from 15 test subjects (Seven males and eight females aged between 20 and 30 years), The experiment were repeated on the participants three times and the subjects’ emotions are induced using approximately four minutes long 15 film clips. The videos are organized in such a way that three emotions (positive, neutral, negative) classes can be examined with five corresponding film clips. In this study, only positive and negative data sets are used to evaluate feature’s performance for binary classification employed a one-minute-long data extracted from the middle part of each trial in the SEED.

2.2 Data preprocessing

EEG data sets are high-dimensional neurophysiological signal which comprises redundant and noisy data. After data acquisition, electrooculogram (EOG) and electromyogram (EMG) artifacts and line interference were removed in the pre-processing step. This data was then downsampled to the sampling frequency of 200 Hz to eradicate the computational complexities in extracting the features. Then the one-minute-long signal was extracted from the central part of each SEED trial, which is the data of ~ 4 min duration.

This work also intends to study the emotion recognition in different frequency bands/rhythms of EEG rather than just the fundamental frequency, which is 0–75 Hz in our data case. Here, the FIR filter is used to extract different EEG rhythms, i.e., θ (4–7 Hz), α (8–15 Hz), β (16–31 Hz), and γ (32–55 Hz). Delta rhythm is not considered in this study, because it is mainly related to deep sleep activity. Before extracting features from these EEG rhythms, data were normalized using the z-score method, which for a random variable ‘Y’ with the mean ‘Ῡ’ and standard deviation ‘δ’ is stated as.

Z = (Y- Ῡ) / δ.

This process contributed to eliminating subject bias and generating more comparable features between subjects while preserving the variability of different channels. Then the required feature was extracted.

2.3 Feature engineering

2.3.1 Tsallis entropy

Entropy, in general, depicts the unpredictability of any signal. The idea is to obtain a temporal variation of Tsallis entropy by incorporating a sliding time window in the input signal, then calculating the mean of the entropy obtained from the buffered signal. Suppose [X(n): n = 1,…, L] is the input signal. A sliding window W is designed such that the width of window ‘w’ is w ⩽ L, and the sliding step is δ ⩽ w. Above defined time-dependent Tsallis entropy in Eq. (2) is then computed in each sliding window where Pi is the probability. The probability defined here is the ratio of the number of X(i)-values of the sliding window and the total number of X(i)-values in the window. The mean and variance of this Tsallis entropy serve as the average local abnormality marker of the EEG signal to be analyzed and help differentiate the positive and negative emotions in different EEG rhythms (Fig. 2).

2.3.2 K-nearest neighbor classifier

K-nearest neighbor algorithm is the simplest of all machine learning algorithms. It is a non-parametric algorithm based on a supervised learning method. It classifies unknown data based on its neighboring data points, as shown in Fig. 2. The classification takes two steps; taking the assigned number of nearest neighbours first, then utilising the results of the first step to categorize the data point into a specific class:

Hence, the performance of the KNN classifier depends on two factors i. ‘k’—the number of neighbors considered, ii. the distance to calculate the nearest data points. Various distance matrices could be used, such as ‘Cityblock,’ ‘Chebyshev,’ ‘Correlation,’ ‘Cosine,’ ‘Euclidean,’ ‘Hamming,’ ‘Jaccard,’ ‘Mahalanobis,’ ‘Minkowski,’ ‘Seuclidean,’ and ‘Spearman’. The parameter ‘k’ which is the number of neighbors could majorly depend on the size of the data considered. Upon computational optimization for the data considered in this work, we opted for ‘k = 10’—number of neighbors and ‘Euclidean’—distance defined in Eq. 4, to build our classifier.

2.3.3 DATA split and validation method

Any machine learning classifier is built with cross-validation partition methods. The cross-validation partition function is used to specify the type of cross-validation, and indexing is used to divide input data in training and testing sets, which depend on the research objectives. The three most basic strategies are ‘holdout,’ ‘k-fold,’ and ‘leave out. This work adapts the ‘hold out’ method for validation. In this method, a fraction of data specified as a scalar value in the range [0 1] is held for testing the model, and the rest of the data is used to train the classifier. We have used 0.2 holdouts in the present work, which means 80% of the features are used for training the k-NN classifier, and 20% is used for the method testing.

2.3.4 Performance evaluation metric

Designed classifiers are commonly evaluated using a confusion matrix-based approach, as shown in Fig. 3, to ensure acceptable and reliable classification outcomes. Four classification metrics—accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and F-score—can be obtained from the confusion matrix for performance comparison. For our study that undertakes a binary classification problem, the four metrics are defined by Eq. 5. The acronyms TP, FP, TN, and FN, stand for true positive, false positive, true negative, and false negative, respectively:

TP and TN are the number of true positive and negative samples correctly classified as positive and negative, respectively. Similarly, FN and FP are the number of true positive and negative samples misclassified as negative and positive, respectively. Accuracy and F-score is considered for the present study (Fig. 3).

3 Results and discussion

All the computations explained above in the material and methods sections were carried out in MATLAB. Initially, the data was pre-processed, and the defined rhythms were extracted and normalized. Further, the Tsallis entropy feature for Tsallis parameter q = 2, 3, 4 was computed the classification of binary emotion was done through the KNN classifier. Finally, hold-out cross-validation was used by splitting each participant’s samples into an 80% training set and a 20% test set, keeping a roughly constant percentage of each class in each set relative to the original data. The classification process was run ten times to decrease the unpredictability induced by the data set’s random partition, and the average classification accuracy was calculated. As indicated, KNN machine learning algorithms were utilized for categorization work. A hyperparameter optimization approach was used to adjust the parameters of the classifiers. The study aims to find how well the Tsallis entropy performs in determining subject independent emotions. It considers the perspectives of different channel locations, all the brain regions, and certain rhythms. The results are shown in Figs. 4, 5, 6.

Overall Evaluation In this study, the performance of 62 channels from the SEED data set was evaluated for Tsallis parameters 2, 3, and 4, with accuracy and F-score presented in Figs. 4A, 5A, and 6A. The top-performing channels (one-fourth of the total) were marked on the brain diagram in Figs. 4B, 5B, and 6B. The results show that electrodes from the temporal lobe on both sides of the brain exhibited superior performance in differentiating positive and negative emotions, irrespective of the subjects.

Subject independent emotion recognition performance A On different channels. B Brain topology describing channel location and nomenclature and indicating 1/4th of the total channels that performed the best. C Performance of different brain hemispheres, D Performance of different rhythms, all taking Tsallis entropy as feature for q = 3

Furthermore, the study explored the performance of different EEG rhythms. Figures 4D, 5C, and 6D reveal that the gamma rhythm (31–55 Hz frequency range) achieved the best performance, followed by the beta rhythm. All frequency bands showed comparable results as well. This indicates that higher frequency rhythms, specifically beta (β) and gamma (γ), play a more critical role in emotion study compared to lower frequency rhythms like theta (θ) and alpha (α).

In the study, the performance of different brain regions was analyzed separately and presented in Figs. 4C, 5D, and 6C. Figure 6B shows the partitioning of the brain regions into eight distinct regions of interest. When evaluating the four quadrants, namely left anterior, right anterior, left posterior, and right posterior regions, electrodes from the intersecting regions were excluded from consideration. The analysis of lower gamma bands from the left and right profiles of the brain revealed that the left anterior and posterior regions exhibited superior performance compared to the right anterior and posterior regions, respectively.

Furthermore, the left hemispheres consistently outperformed the right hemispheres across all frequency bands and cases. Moreover, when comparing the results between posterior and anterior regions, the features from the anterior hemispheres consistently demonstrated better classification performance across all frequency bands.

3.1 Comparative study of Tsallis parameter q-based performance

The study acknowledges the significance of different values of q in entropy computation for EEG research, as extensively discussed in the literature [47,48,49,50]. The proposed method's performance is compared based on accuracy and F-score metrics. While accuracy represents the proportion of correct predictions made by the classification model, it can be misleading when used as the sole criterion for assessing performance. This is because accuracy depends on correctly predicted positive and negative classes, and higher accuracy with a higher number of incorrect predictions may indicate poor performance. To address this limitation, the study incorporates the F-score matrix for performance evaluation. The F-score considers the impact of false negatives and false positives, making it particularly relevant when studying negative emotions and providing a more comprehensive assessment of the proposed method’s performance. By considering both accuracy and F-score, the study aims to provide a more robust evaluation of the classification method's effectiveness in emotion differentiation using EEG data.

The findings from Figs. 4, 5, and 6 highlight the superior performance of the gamma band in comparison to other frequency bands. Further analysis focuses on the numbers obtained from the gamma band's performance matrices. For ‘q = 2’, the maximum accuracy–F-score pair is 79%–0.83, and the best average accuracy–F-score pair is 71%–0.69. For ‘q = 3’, the maximum accuracy–F-score pair is 84%–0.87, and the best average accuracy–F-score pair is 79%–0.81. For ‘q = 4’, the maximum accuracy–F-score pair is 80%–0.82, and the best average accuracy–F-score pair is 71%–0.68. The study reveals that ‘q = 3’ outperforms the other values of q, although the differences between ‘q = 2’ and ‘q = 3’ are not substantial. The presence of relatively low F-scores compared to accuracy for ‘q = 2’ and ‘q = 4’ indicates higher false negative and false positive rates in the predictions, emphasizing the need for cautious interpretation of results based solely on accuracy. On the other hand, ‘q = 3’ exhibits competitive accuracy and F-score, making it an excellent choice for further study. This underscores the importance of carefully selecting the nonextensive parameter q and the need for additional research to optimize its value for different studies.

A comparative analysis of Figs. 4B, 5B, and 6B identifies common electrode positions that consistently performed well across all cases of q. These electrodes include FT7, FT8, T7, C5, C6, T8, TP7, CP5, TP8, P7, and P8. These positions can be considered for further emotion studies using the SEED data set.

4 Conclusion

In this work, we have explored a novel emotion recognition method based on Tsallis entropy and the KNN Classifier, using the SEED (EEG) data set. The study successfully addressed the research questions outlined in Sect. 1.6.

The proposed method achieved the best average accuracy of 79% and a maximum accuracy of 84%, accompanied by F-scores of 0.81 and 0.87 for q = 3. This finding confirms that Tsallis entropy is effective in assessing chaotic situations in EEG signals, encompassing inconsistencies, complexities, and unpredictability. As a result, Tsallis entropy holds significant relevance in emotion recognition tasks.

Our study further found that the model's performance is influenced by the Tsallis parameter q, although the variation is not deemed significant, as discussed in response to the second research question. However, the paper does not delve into the detailed explanation for this variation, considering it beyond the scope of the current study. Nevertheless, a comparison of the present study's results with previous works presented in Table 1 demonstrates that Tsallis entropy indeed yields competitive performance compared to various state-of-the-art techniques, thereby addressing the third research question. The study highlights the crucial role of the gamma rhythm in generating efficient features that lead to higher performance in emotion recognition, aligning with previous literature. This reaffirms the significance of the gamma rhythm in EEG-based emotion studies. The proposed method's advantage lies in the simplicity of Tsallis entropy, which possesses low computational complexity and nonlinearity. The TsEn features effectively extract hidden complexities in EEG signals, resulting in improved accuracy.

However, the study also acknowledges several limitations. One major limitation is the necessity to optimize the entropy index ‘q’ for each specific research task, which can be a challenging and time-consuming process. In addition, the classification accuracy achieved by the proposed method is not very high, indicating the need for further modifications and improvements. In future work, the authors plan to enhance the model’s performance by integrating the extracted features with deep learning models. This could potentially lead to increased accuracy and more robust emotion recognition. The proposed method will also be evaluated on other emotion data sets to ensure its reliability and generalizability across different data sets and scenarios. This will provide a comprehensive assessment of the method’s effectiveness in real-world emotion recognition applications.

Availability of data and materials

The SEED database used in the present analysis can be found at http://bcmi.sjtu.edu.cn/home/seed/seed.html.

References

Scherer KR (2005) What are emotions? And how can they be measured? Soc Sci Inf 44:695–729

Ekman P, Friesen WV, O’sullivan M et al (1987) Universals and cultural differences in the judgments of facial expressions of emotion. J Pers Soc Psychol 53:712

Lang PJ (1995) The emotion probe: studies of motivation and attention. Am Psychol 50:372

Liu Y, Sourina O, Nguyen MK (2010) Real-time EEG-based human emotion recognition and visualization. In: 2010 international conference on cyberworlds. pp. 262–269

Anderson K, McOwan PW (2006) A real-time automated system for the recognition of human facial expressions. IEEE Trans Syst Man, Cybern Part B 36:96–105

Ang J, Dhillon R, Krupski A, et al (2002) Prosody-based automatic detection of annoyance and frustration in human-computer dialog. In: Seventh International Conference on Spoken Language Processing. pp 2037–2040

Haas LF (2003) Hans Berger (1873–1941), Richard Caton (1842–1926), and electroencephalography. J Neurol Neurosurg; Psychiatry 74:9-LP9. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.74.1.9

Herwig U, Satrapi P, Schönfeldt-Lecuona C (2003) Using the international 10–20 EEG system for positioning of transcranial magnetic stimulation. Brain Topogr 16:95–99

Kim KH, Bang SW, Kim SR (2004) Emotion recognition system using short-term monitoring of physiological signals. Med Biol Eng Comput 42:419–427

Gao Y, Wang X, Potter T et al (2020) Single-trial EEG emotion recognition using granger causality/transfer entropy analysis. J Neurosci Methods 346:108904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2020.108904

Acharya UR, Fujita H, Sudarshan VK et al (2015) Application of entropies for automated diagnosis of epilepsy using EEG signals: a review. Knowledge-Based Syst 88:85–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2015.08.004

Patel P, Annavarapu RN (2023) Analysis of EEG Signal using nonextensive statistics. Int Res J Eng Technol. pp.1632–1649

Patel P, Annavarapu RN (2021) EEG-based human emotion recognition using entropy as a feature extraction measure. Brain Informatics 8:1–13

Patel P, Balasubramanian S, Annavarapu RN (2023) Tsallis entropy as biomarker to assess and identify human emotion via EEG rhythm analysis. NeuroQuantology 21:135–149. https://doi.org/10.48047/nq.2023.21.01.NQ20009

Shannon CE (1948) A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst Tech J 27:379–423

Cherian R, Kanaga EG (2022) Theoretical and methodological analysis of EEG based seizure detection and prediction: an exhaustive review. J Neurosci Methods 369:109483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2022.109483

Li X, Ouyang G, Richards DA (2007) Predictability analysis of absence seizures with permutation entropy. Epilepsy Res 77:70–74

Acharya UR, Sree SV, Swapna G et al (2013) Automated EEG analysis of epilepsy: a review. Knowledge-Based Syst 45:147–165

Zhao P, Van-Eetvelt P, Goh C et al (2007) Characterization of EEGs in Alzheimer’s disease using information theoretic methods. IEEE Eng Med Biol Mag 1:5127

Coronel C, Garn H, Waser M et al (2017) Quantitative EEG markers of entropy and auto mutual information in relation to MMSE scores of probable Alzheimer’s disease patients. Entropy 19:130

De Bock TJ, Das S, Mohsin M, et al (2010) Early detection of Alzheimer’s disease using nonlinear analysis of EEG via Tsallis entropy. In: 2010 Biomedical Sciences and Engineering Conference. pp 1–4

Movahed RA, Jahromi GP, Shahyad S, Meftahi GH (2021) A major depressive disorder classification framework based on EEG signals using statistical, spectral, wavelet, functional connectivity, and nonlinear analysis. J Neurosci Methods 358:109209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2021.109209

Cai H, Han J, Chen Y et al (2018) A pervasive approach to EEG-based depression detection. Complexity 2018:1

Bos DO et al (2006) EEG-based emotion recognition. Influ Vis Audit Stimuli 56:1–17

Mohammadi Z, Frounchi J, Amiri M (2017) Wavelet-based emotion recognition system using EEG signal. Neural Comput Appl 28:1985–1990

Lotfalinezhad H, Maleki A (2019) Application of multiscale fuzzy entropy features for multilevel subject-dependent emotion recognition. Turkish J Electr Eng Comput Sci 27:4070–4081

Tong J, Liu S, Ke Y, et al (2017) EEG-based emotion recognition using nonlinear feature. In: 2017 IEEE 8th International Conference on Awareness Science and Technology (iCAST). pp 55–59

García-Martínez B, Martínez-Rodrigo A, Zangróniz R et al (2017) Symbolic analysis of brain dynamics detects negative stress. Entropy 19:196

Yin Z, Liu L, Liu L et al (2017) Dynamical recursive feature elimination technique for neurophysiological signal-based emotion recognition. Cogn Technol Work 19:667–685

Alazrai R, Homoud R, Alwanni H, Daoud MI (2018) EEG-based emotion recognition using quadratic time-frequency distribution. Sensors 18:2739

Cai J, Chen W, Yin Z (2019) Multiple transferable recursive feature elimination technique for emotion recognition based on EEG signals. Symmetry 11:683

García-Martínez B, Martínez-Rodrigo A, Fernández-Caballero A et al (2020) Nonlinear predictability analysis of brain dynamics for automatic recognition of negative stress. Neural Comput Appl 32:13221–13231

Chen D-W, Miao R, Yang W-Q et al (2019) A feature extraction method based on differential entropy and linear discriminant analysis for emotion recognition. Sensors 19:1631

Martínez-Rodrigo A, García-Martínez B, Alcaraz R et al (2019) Multiscale entropy analysis for recognition of visually elicited negative stress from EEG recordings. Int J Neural Syst 29:1850038

Guo K, Chai R, Candra H et al (2019) A hybrid fuzzy cognitive map/support vector machine approach for EEG-based emotion classification using compressed sensing. Int J Fuzzy Syst 21:263–273

Martínez-Rodrigo A, García-Martínez B, Zunino L et al (2019) Multi-lag analysis of symbolic entropies on EEG recordings for distress recognition. Front Neuroinform 13:40

Bhattacharyya A, Tripathy RK, Garg L, Pachori RB (2020) A novel multivariate-multiscale approach for computing EEG spectral and temporal complexity for human emotion recognition. IEEE Sens J 21:3579–3591

Tsallis C (1999) Nonextensive statistics: theoretical, experimental and computational evidences and connections. Brazilian J Phys 29:1–35

Tsallis C (1988) Possible generalization of Boltzmann-Gibbs statistics. J Stat Phys 52:479–487

Gell-Mann M, Tsallis C (2004) Nonextensive entropy: interdisciplinary applications. Oxford University Press on Demand, Oxford

Schaul N (1998) The fundamental neural mechanisms of electroencephalography. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 106:101–107

Rosso OA, Martin MT, Plastino A (2002) Brain electrical activity analysis using wavelet-based informational tools. Phys A Stat Mech its Appl 313:587–608

Contreras D, Destexhe A, Sejnowski TJ, Steriade M (1997) Spatiotemporal patterns of spindle oscillations in cortex and thalamus. J Neurosci 17:1179–1196

Capurro A, Diambra L, Lorenzo D et al (1999) Human brain dynamics: the analysis of EEG signals with Tsallis information measure. Phys A Stat Mech its Appl 265:235–254

Tong S, Bezerianos A, Malhotra A et al (2003) Parameterized entropy analysis of EEG following hypoxic–ischemic brain injury. Phys Lett A 314:354–361

Zheng W, Liu W, Lu Y, et al (2018) SJTU Emotion EEG Dataset for F our E motions (SEED -IV) License Agreement. pp. 6–7

Zhang D, Jia X, Thakor N, et al (2009) Features of burst-suppression EEG after asphyxial cardiac arrest in rats. In: 2009 4th International IEEE/EMBS Conference on Neural Engineering. pp. 518–521

Bezerianos A, Tong S, Thakor N (2003) Time-dependent entropy estimation of EEG rhythm changes following brain ischemia. Ann Biomed Eng 31:221–232. https://doi.org/10.1114/1.1541013

Zhang A, Bi J, Sun S (2013) A method for drowsiness detection based on Tsallis entropy of EEG. World congress on medical physics and biomedical engineering, May 26–31, 2012, Beijing China. Springer, Berlin, pp 505–508

Lofgren NA, Outram N, Thordstein M (2007) EEG entropy estimation using a Markov model of the EEG for sleep stage separation in human neonates. In: 2007 3rd International IEEE/EMBS Conference on Neural Engineering. pp 634–637

Chu W-L, Huang M-W, Jian B-L, Cheng K-S (2017) Analysis of EEG entropy during visual evocation of emotion in schizophrenia. Ann Gen Psychiatry 16:1–9

García-Martínez B, Martínez-Rodrigo A, Zangróniz Cantabrana R et al (2016) Application of entropy-based metrics to identify emotional distress from electroencephalographic recordings. Entropy 18:221

Lu Y, Wang M, Wu W et al (2020) Dynamic entropy-based pattern learning to identify emotions from EEG signals across individuals. Measurement 150:107003

Yao L, Wang M, Lu Y et al (2021) EEG-based emotion recognition by exploiting fused network entropy measures of complex networks across subjects. Entropy 23:984

Kumar M, Molinas M (2022) Human emotion recognition from EEG signals: model evaluation in DEAP and SEED datasets. In: Proceedings of the First Workshop on Artificial Intelligence for Human-Machine Interaction (AIxHMI 2022) co-located with the 21th International Conference of the Italian Association for Artificial Intelligence (AI* IA 2022), CEUR Workshop Proceedings, CEU

Zheng F, Hu B, Zheng X et al (2022) Dynamic differential entropy and brain connectivity features based EEG emotion recognition. Int J Intell Syst 37:12511–12533

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Pondicherry University for financial support through University Fellowship.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PP: conceptualization, computation, formal analysis, and writing—original draft. SB: computation and validation. RNA: reviewing, editing, and supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent for publication

All authors consent to the publication of this article.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Patel, P., Balasubramanian, S. & Annavarapu, R.N. Cross subject emotion identification from multichannel EEG sub-bands using Tsallis entropy feature and KNN classifier. Brain Inf. 11, 7 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40708-024-00220-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40708-024-00220-3