Abstract

Palpitations are reported commonly by women around the time of menopause as skipped, missed, irregular, and/or exaggerated heartbeats or heart pounding. However, much less is known about palpitations than other menopausal symptoms such as vasomotor symptoms. The objective of this review was to integrate evidence on menopausal palpitations measures. Keyword searching was done in PubMed, CINAHL, and PsycINFO for English-language, descriptive articles containing data on menopause and palpitations and meeting other pre-specified inclusion criteria. Of 670 articles, 110 met inclusion criteria and were included in the review. Results showed that 11 different measures were used across articles, with variability within and between measures. Inconsistencies in the wording of measurement items, recall periods, and response options were observed even when standardized measures were used. Most measures were limited to assessing symptom presence and severity. Findings suggest that efforts should be undertaken to (1) standardize conceptual and operational definitions of menopausal palpitations and (2) develop a patient-friendly, conceptually clear, psychometrically sound measure of menopausal palpitations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Palpitations are more common in women than in men [1]. Women may experience palpitations during peri- and post-menopause, along with vasomotor and other menopausal symptoms [1,2,3]. Although much has been written about menopausal vasomotor symptoms [4, 5], less has been reported about menopausal palpitations. Menopausal women report feeling skipped, missed, irregular, and/or exaggerated heartbeats or heart pounding [6, 7]. A recently completed review found that palpitations prevalence was 4 to 40% in premenopausal women, 20 to 40% in perimenopausal women, and 16 to 54% in postmenopausal women [8]. The review also showed that the prevalence was significantly higher among perimenopausal and surgically postmenopausal women in comparison to premenopausal or postmenopausal women [8]. Although the number of articles reviewed was small (n = 5), differences in palpitations assessment tools limited the ability to make comparisons across articles.

Palpitations are associated with some negative health outcomes in the general population and in menopausal women. In the general population, palpitations (1) account for 16% of general physicians’ visits [9], (2) are the second leading reason for cardiologist visits [9], and (3) are related to increased risk for cardiac arrythmias when they affect sleep and work [10]. In peri- and postmenopausal women, menopausal palpitations distress is associated with worse sleep disturbance [11], depressive symptoms [3, 11, 12], stress [11], and menopausal quality of life [11]. The directions of these associations are unclear as these were cross-sectional analyses. Comprehensive assessment methods are critical to understanding palpitations and improving menopausal quality of life.

There do not appear to be any existing published reviews of menopausal palpitations measures. It is important to understand how palpitations have been measured. First, palpitations are likely experienced by women globally during their transition through menopause [8]. Using the same measure of palpitations can facilitate comparisons across studies to help understand inter-individual differences in symptoms by race, ethnicity, geographic region, and other cultural variables [13]. Second, examining current measures of palpitations can help to explicate what symptom dimensions have and have not been explored. The Theory of Unpleasant Symptoms posits that symptoms can be measured on multiple dimensions [14]. Symptom dimensions that can yield important information for clinical practice and research include presence, frequency, severity or intensity, bother or distress, interference or impact, temporal pattern, duration, quality, degree of unpredictability, perceived control over, and symptom representations. More frequent palpitations may be associated with serious arrhythmias in the general population [15], which can indicate serious cardiovascular disease. In the absence of cohesive information regarding palpitations measures, it is unclear whether and to what degree various symptom dimensions are being assessed and reported. The purpose of this review was to integrate evidence on menopausal palpitations measures.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

The review was conducted with pre-specified inclusion criteria. Articles had to be 1) full-length, 2) peer-reviewed, 3) descriptive research, 4) English-language, 5) conducted in menopausal women (samples described as midlife, menopausal, peri- and/or post-menopausal consistent with Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW) or STRAW+ 10 definitions) [16,17,18], and 6) inclusive of data on menopausal palpitations or similar symptoms such as racing or pounding heart. We selected descriptive research to be consistent with current recommendations for excluding clinical trials in measurement-focused reviews [19]. Articles that included premenopausal women as a comparison group were included but articles that focused exclusively on premenopausal women were excluded. Other exclusion criteria were articles that 1) included transgender or gender transitioning populations, men, or animals, or 2) defined study populations as “menopausal women” or “symptomatic women” without additional information.

Literature search strategy

A librarian (CAP) completed the search on May 19, 2020 with no restriction on publication date to reflect all available published articles up to that date. PubMed, Cumulated Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and PsycINFO search engines were selected because of their comprehensiveness and usefulness for health-related literature. Search strategy included the MeSH terms and key words: (“Menopause” OR menopaus*) AND (palpitation* OR heart racing OR heart pounding OR irregular heart). The search term “palpitations” was too specific to locate pertinent articles. Additional searches were done by searching for articles that employed menopausal-symptom assessment tools from the three search engines. Tools searched included the Menopause Rating Scale (Heinemann) [20], Greene Climacteric Symptom Rating Scale [21], Midlife Women’s Symptom Index [22], Holte/Mikkelsen Menopause Checklist [23], Hunter’s Women’s Health Questionnaire [24], Neugarten and Kraines’ Symptom Checklist [25], Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) menopausal symptom checklist, Menopause Symptoms List [26], the Blatt Kupperman Index [27,28,29], Menopause Symptoms Checklist [26], and Menopausal-Specific Quality of Life (MENQOL) [30].

We organized the review using Covidence.org, a structured program available through a university subscription. We used Covidence features to remove duplicates from searches, track the progress of multiple raters during screening and full-text review, and calculate inter-rater reliabilities. A separate literature search or review protocol was not published. The review did not meet the definition of human subject research and did not require institutional review board approval.

Screening process

After completing the searches, one author deduplicated the list of potential articles. Next, article titles and abstracts (n = 670) were independently and sequentially screened by two of three authors. To be overly inclusive, screeners included articles if titles and abstracts mentioned (1) menopausal or climacteric symptoms/syndrome or (2) one of the aforementioned menopausal symptom assessment tools as a study measure. Where disagreements occurred (8.8%), the three reviewers discussed each article and achieved consensus.

Following an initial screening, there were 608 articles remaining, and full texts were retrieved by the team for review. Two authors independently and sequentially read each article and voted on their inclusion or exclusion. The data presentation for symptom surveys or the previously mentioned symptom assessment tools were carefully reviewed. Articles were excluded if there were no specific data on palpitations reported. Disagreements (5.0%) were again resolved through discussion.

Data extraction process

Using data extraction forms that we created, one author extracted the data and two additional authors verified accuracy. Disagreements were resolved through discussion. Extracted data included article metadata (title, author, year, country, design) and palpitations measurement details (name, item, recall period, response options, symptom dimensions assessed). We did not assess quality and bias because the review was focused only on the measurement tool that was used and not the study sample, analysis or results.

In summarizing the data from the extraction process, we focused on number of articles and not the number of studies. Some author groups produced multiple articles from the same study but there were sometimes slight differences in sample sizes, characteristics, or data reported. For example, Blümel et al. (2011, 2012, 2016) [31,32,33] and Monterrosa, Blümet et al. (2007, 2009, 2013) [34,35,36] were from the multicentric Collaborative Group for Research of the Climacteric in Latin America (REDLINC) III, or IV, or V study. However, because our focus was on articles, we did not report these as one study or three waves of the same study because they had different samples, purposes, and/or data. Other authors produced multiple articles, but these were not always from the same study. For example, four articles by Chedrai [37,38,39,40] included Ecuadorian women but each article reflected a different sample. Thus, we use the term “articles” throughout this review rather than “studies”.

Results

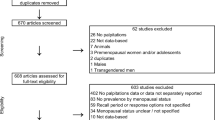

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram [41] is shown in Fig. 1. After searching the databases, 1574 articles were retrieved, leaving 670 articles after duplicates were removed. After screening titles and abstracts for the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 62 articles were excluded. Six hundred and eight full-text articles were screened, from which 498 were excluded because they did not report palpitations data; they were not descriptive research, data-based articles, or full-length articles; they included wrong sample; or the articles were withdrawn. This left 110 articles for the review.

Measurement tools

Table 1 provides information regarding the different measurement tools used in the reviewed articles. Most articles used standardized instruments (76%) and the remaining articles used other measurement methods like unspecified self-administered questionaries or interviews (24%). The most common assessment method was the Menopause Rating Scale (n = 69) [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40, 42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100]. The next three most common assessment methods were unspecified self-administered questionaries (n = 14) [115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128], interviews (n = 10) [7, 129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137], and the Blatt Kupperman Menopause Index (n = 8) [12, 44, 101,102,103,104,105,106]. With the exception of interviews, all measures used a single item to assess palpitations. In all articles, palpitations were measured along with other menopausal symptoms.

Table 1 also shows the wide variation in items, recall periods, and response options within and between the measures. The Menopause Rating Scale provides one example of measurement item variation. Rather than using the standardized item, articles reported the item as heart discomfort (with and without further specification), palpitations, or cardiac symptoms. Recall periods were mostly missing, and only 14 articles (12.7%) included recall periods. These reported recall periods ranged from 1 week to 1 year [7, 77,78,79,80,81, 83, 89, 122, 125, 131, 133,134,135]. Response options varied from yes/no to Likert scales. Most of the Likert scales measured symptom presence and severity (e.g., 0 no symptom, 1 mild, 2 moderate, 3 severe, 4 very severe) and only a few measured symptom frequency (e.g., 0 not at all, 1 sometimes, 2 often, 3 always) [12, 125].

Concepts assessed by measurement tools

Table 2 maps the measurement items in Table 1 to various concepts being assessed including palpitations (not otherwise specified), sensations related to heart rate (e.g., heart racing), sensations related to heartbeat (e.g., heart pounding), and discomfort. None of the items had the same meaning or assessed the same concepts. What was assessed depended on the details of the items being used. For example, the underlying symptom concept assessed with heart discomfort (e.g., discomfort) was different from that assessed with an item of rapid heartbeat (e.g., sensations related to heartbeat).

Symptom dimensions assessed by measurement tools

Table 3 maps the measurement items in Table 1 to symptom dimensions of presence, severity (or intensity), distress (or bother), frequency, and interference (or impact). Most articles in this review used uni- or bi-dimensional measures (presence and/or severity). Two articles reported modifying bi-dimensional measures (presence, severity) based on participants’ feedback during pretesting [83, 89]. Likert response options were simplified to yes/no, making them uni-dimensional measures (presence) [83, 89]. Only seven (6.4%) articles measured dimensions such as distress/bother, frequency, or interference/impact of the palpitations [12, 104, 106, 113, 125, 126, 133]. Very few measures were multi-dimensional, and these assessed three or four symptom dimensions. No articles measured the following dimensions: temporal pattern, duration, quality, degree of unpredictability, perceived control over, or symptom representations.

Discussion

Menopausal palpitations have been assessed using a variety of items on measures that were developed to assess multiple menopausal symptoms. This review documents the amount of variation in these measures’ items, recall periods, and response options both as they occur within a standardized measure and across standardized and unstandardized measures. In addition, this review documents the relatively limited way in which menopausal palpitations have been assessed to date using mostly single items with varying differentiation of concepts and a limited number of symptom dimensions.

There was a lack of conceptual and operational consistency identified in this review, making it impossible to provide a recommendation for which measure may be superior to others. The inconsistencies in items, recall periods, and response options indicated different concepts were assessed, which prohibits integrating research findings across articles. Variations were evident in whether palpitations were assessed as sensations related to heart beats, heart rate, discomfort, tightness, anxiety, and/or breathlessness. The words used to assess menopausal palpitations were numerous and included some that participants with low health literacy may not understand (i.e., palpitations, tachycardia). In addition, the few articles that provided a recall period indicated the symptom was assessed using different recall time frames. Assessing symptoms in the past week could lead to more accurate recall but would omit data about prior history of palpitations, whereas assessing over the past year could lead to imprecise estimations or memory recall bias but more historical information [140]. Measuring palpitations over a variety of time periods may provide the most comprehensive information. Furthermore, although most response options were presence and/or severity, the descriptions varied. For example, in 5-point response options, the meaning of 0 varied from no symptom to no discomfort and the meaning of upper scores varied from very severe symptom to unbearable or severe discomfort. The response options determine the way participants interpret and respond to the question [140]. It is possible that some participants may have had palpitations but did not experience discomfort from them, and thus, might have rated 0 no discomfort or 1 symptom present depending on how the item was worded. The variation in how palpitations are assessed limits the consistency and comparability of findings across articles.

It is impossible to differentiate how much of the operational and conceptual inconsistency was due to how the item was presented to study participants or how the instrument was described in published reports. Operational inconsistencies seemed to exist even within the most used standardized tool, the Menopause Rating Scale. The original article for the Menopause Rating Scale lists the item as “Heart discomfort (unusual awareness of heartbeat, heart skipping, heart racing, tightness)” [141, 142]. Most articles did not include all of the details in the parentheses in describing the item used for assessment and as noted above, did not report recall periods, and/or used varied response options. Conceptual and operational clarity cannot be reached until palpitations are well defined, and there is clarity surrounding which words should be used to describe the symptom.

Because symptoms are multidimensional [14], measures should assess multiple dimensions. Our finding that measures were mostly limited to assessing presence and severity is similar to findings from another review showing that cancer symptom measures are also limited to symptom presence and severity [143]. Multiple dimensions of palpitations have rarely been evaluated in the context of menopausal articles [12, 46, 82, 114, 124]. Multidimensional measures capture multiple characteristics and manifestations of symptoms compared to measures that focus on only one or two dimensions [144]. Assessing a greater number of symptom dimensions will provide a more detailed picture of the symptom profile and its complexity [145]. Measuring multiple palpitations dimensions can advance our understanding of the symptom and can help determine the efficacy and effectiveness of interventions [146].

Defining the concept of palpitations, including domain and subdomains, is a critical first step in measure development [147]. Because greater conceptual clarity can be reached by reviewing and synthesizing evidence from the literature and noting the field’s limitations [146], this review has helped to document where the field could move forward. In addition, talking with women about their palpitation symptom experience can help to generate items. Subsequently, receiving experts’ critique and review of such items will also strengthen measure development.

Strengths and limitations of the review

Strengths of this review were the number of articles that we identified using multiple comprehensive databases which reduced the possibility of missing relevant articles. In addition, there were multiple authors involved at each stage of the review, which reduced the likelihood of subjectivity or inaccuracies.

The review also has some limitations. We only included English language articles, which may have led to the exclusion of some relevant articles. Choice of search terms is another limitation, which may have resulted in exclusion of some relevant articles. For example, the search picked up Obermeyer et al. [131], but not Obermeyer et al. [148]. However, the choice of search terms was difficult as there are no standard MeSH terms or other subject heading terms and no standardized measures for palpitations. We did not extract information on reliability and validity because these were not reported for the single item related to palpitations. We cannot derive a comprehensive definition of menopausal palpitations in this review since we aimed to explore how palpitations were measured. Nevertheless, we provided evidence of how the palpitations were measured and which symptom dimensions have and have not been measured.

Conclusions

This review indicates that although palpitations have been assessed in menopausal women, nearly all assessments have been limited to single items. There was a lack of consistency on item wordings and response options, limited information on recall periods that were used, and a limited number and type of symptom dimensions that have been measured. The information in this review provides evidence for a need to create a multidimensional measure of menopausal palpitations. The review also serves as a cautionary tale for research on other menopausal symptoms because the measurement inconsistencies we identified are also problematic for all other menopausal symptoms assessed on these measures.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Keeler ER, Morris RK, Patolia DS, Toy EC. The evaluationand management of palpitations. Primary Care Update Ob/Gyns. 2002;9(6):199–205.

Bruce D, Rymer J. Symptoms of the menopause. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;23(1):25–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2008.10.002.

Lin HL, Hsiao MC, Liu YT, Chang CM. Perimenopause and incidence of depression in midlife women: a population-based study in Taiwan. Climacteric. 2013;16(3):381–6.

Costanian C, Zangiabadi S, Bahous SA, Deonandan R, Tamim H. Reviewing the evidence on vasomotor symptoms: the role of traditional and non-traditional factors. Climacteric. 2020;23(3):213–23.

Noll PRES, Campos CAS, Leone C, Zangirolami-Raimundo J, Noll M, Baracat EC, et al. Dietary intake and menopausal symptoms in postmenopausal women: a systematic review. Climacteric. 2021;24(2):128–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/13697137.2020.1828854.

Cho L. Ever since I started menopause, my heart flutters from time to time. It usually lasts several seconds. Is this normal? Heart Advis. 2006;9(10):8.

Sievert LL, Obermeyer CM. Symptom clusters at midlife: a four-country comparison of checklist and qualitative responses. Menopause. 2012;19(2):133–44. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e3182292af3.

Carpenter JS, Sheng Y, Elomba C, Alwine J, Yue M, Pike CA, et al. A systematic review of palpitations prevalence by menopausal status. Invited review. Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep. 2021;10(1):7–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13669-020-00302-z.

Raviele A, Giada F, Bergfeldt L, Blanc JJ, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Mont L, et al. Management of patients with palpitations: a position paper from the European heart rhythm association. Europace. 2011;13(7):920–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/eur130.

Thavendiranathan P, Bagai A, Khoo C, Dorian P, Choudhry NK. Does this patient with palpitations have a cardiac arrhythmia? JAMA. 2009;302(19):2135–43. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.1673.

Carpenter JS, Tisdale JE, Chen CX, Kovacs R, Larson JC, Guthrie KA, et al. A Menopause Strategies–Finding Lasting Answers for Symptoms and Health (MsFLASH) investigation of self-reported menopausal palpitation distress. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2021;30(4):533-38. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2020.8586.

Fu JX, Luo Y, Chen MZ, Zhou YH, Meng YT, Wang T, et al. Associations among menopausal status, menopausal symptoms, and depressive symptoms in midlife women in Hunan Province. China Climacteric. 2020;23(3):259–66.

National Research Council. Indicators. The importance of common metrics for advancing social science theory and research: a workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. p. 31–52.

Lenz ER, Pugh LC, Milligan RA, Gift A, Suppe F. The middle-range theory of unpleasant symptoms: an update. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1997;19(3):14–27. https://doi.org/10.1097/00012272-199703000-00003.

Clementy N, Fourquet A, Andre C, Bisson A, Pierre B, Fauchier L, et al. Benefits of an early management of palpitations. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(28):e11466.

Soules MR, Sherman S, Parrott E, Rebar R, Santoro N, Utian W, et al. Executive summary: stages of reproductive aging workshop (STRAW) Park City, Utah, July, 2001. Menopause. 2001;8(6):402–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00042192-200111000-00004.

Utian WH. Semantics, menopause-related terminology, and the STRAW reproductive aging staging system. Menopause. 2001;8(6):398–401.

Harlow SD, Gass M, Hall JE, Lobo R, Maki P, Rebar RW, et al. Executive summary of the stages of reproductive aging workshop +10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging. Climacteric. 2012;15(2):105–14. https://doi.org/10.3109/13697137.2011.650656.

De Vet HCW, Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, Knol DL. Index. In: Terwee CB, Knol DL, De Vet HCW, Mokkink LB, editors. Measurement in medicine: a practical guide (Practical guides to biostatistics and epidemiology). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2011. p. 328–338.

Heinemann LA, DoMinh T, Strelow F, Gerbsch S, Schnitker J, Schneider HP. The menopause rating scale (MRS) as outcome measure for hormone treatment? A validation study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:67.

Greene JG. Constructing a standard climacteric scale. Maturitas. 1998;29(1):25–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-5122(98)00025-5.

Im EO. The midlife Women's symptom index (MSI). Health Care Women Int. 2006;27(3):268–87.

Holte A, Mikkelsen A. The menopausal syndrome: a factor analytic replication. Maturitas. 1991;13(3):193–203.

Hunter M. The south-East England longitudinal study of the climacteric and postmenopause. Maturitas. 1992;14(2):117–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-5122(92)90004-N.

Neugarten BL, Kraines RJ. "menopausal symptoms" in women of various ages. Psychosom Med. 1965;27(3):266–73. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-196505000-00009.

Perz JM. Development of the menopause symptom list: a factor analytic study of menopause associated symptoms. Women Health. 1997;25(1):53–69.

Delaplaine RW, Bottomy JR, Blatt M, Wiesbader H, Kupperman HS. Effective control of the surgical menopause by estradiol pellet implantation at the time of surgery. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1952;94(3):323–33.

Blatt MH, Wiesbader H, Kupperman HS. Vitamin E and climacteric syndrome; failure of effective control as measured by menopausal index. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1953;91(6):792–9.

Kupperman HS, Wetchler BB, Blatt MH. Contemporary therapy of the menopausal syndrome. J Am Med Assoc. 1959;171:1627–37.

Hilditch JR, Lewis J, Peter A, van Maris B, Ross A, Franssen E, et al. A menopause-specific quality of life questionnaire: development and psychometric properties. Maturitas. 1996;24(3):161–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-5122(96)01038-9.

Blümel JE, Chedraui P, Baron G, Belzares E, Bencosme A, Calle A, et al. A large multinational study of vasomotor symptom prevalence, duration, and impact on quality of life in middle-aged women. Menopause. 2011;18(7):778–85. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e318207851d.

Blümel JE, Chedraui P, Baron G, Belzares E, Bencosme A, Calle A, et al. Menopausal symptoms appear before the menopause and persist 5 years beyond: a detailed analysis of a multinational study. Climacteric. 2012;15(6):542–51. https://doi.org/10.3109/13697137.2012.658462.

Blümel JE, Fica J, Chedraui P, Mezones-Holguín E, Zuñiga MC, Witis S, et al. Sedentary lifestyle in middle-aged women is associated with severe menopausal symptoms and obesity. Menopause. 2016;23(5):488–93. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000000575.

Monterrosa A, Blumel JE, Chedraui P. Increased menopausal symptoms among afro-Colombian women as assessed with the menopause rating scale. Maturitas. 2008;59(2):182–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2007.12.002.

Monterrosa A, Blumel JE, Chedraui P, Gomez B, Valdez C. Quality of life impairment among postmenopausal women varies according to race. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2009;25(8):491–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/09513590902972091.

Monterrosa-Castro A, Blümel JE, Portela-Buelvas K, Mezones-Holguín E, Barón G, Bencosme A, et al. Type II diabetes mellitus and menopause: a multinational study. Climacteric. 2013;16(6):663–72. https://doi.org/10.3109/13697137.2013.798272.

Chedraui P, Aguirre W, Hidalgo L, Fayad L. Assessing menopausal symptoms among healthy middle aged women with the menopause rating scale. Maturitas. 2007;57(3):271–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2007.01.009.

Chedraui P, Pérez-López FR, Hidalgo L, Villacreses D, Domínguez A, Escobar GS, et al. Evaluation of the presence and severity of menopausal symptoms among postmenopausal women screened for the metabolic syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2014;30(12):918–24.

Chedraui P, Pérez-López FR, Mendoza M, Morales B, Martinez MA, Salinas AM, et al. Severe menopausal symptoms in middle-aged women are associated to female and male factors. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;281(5):879–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-009-1204-z.

Chedraui P, San Miguel G, Avila C. Quality of life impairment during the female menopausal transition is related to personal and partner factors. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2009;25(2):130–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/09513590802617770.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Hinrichsen G, Wernecke K-D, Schalinski A, Borde T, David M. Menopausal symptoms in an intercultural context: a comparison between German women, Chinese women and migrant Chinese women using the menopause rating scale (MRS II). Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;290(5):963–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-014-3314-5.

Sweed HS, Elawam AE, Nabeel AM, Mortagy AK. Postmenopausal symptoms among Egyptian geripausal women. East Mediterr Health J. 2012;18(3):213–20. https://doi.org/10.26719/2012.18.3.213.

Tao MF, Sun DM, Shao HF, Li CB, Teng YC. Poor sleep in middle-aged women is not associated with menopause per se. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2016;49(1):e4718. https://doi.org/10.1590/1414-431x20154718.

Thapa R, Yang Y, Bekemeier B. Menopausal symptoms and associated factors in women living with HIV in Cambodia. J Women Aging. 2019;32(5):517–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952841.2019.1593773.

Abdullah B, Moize B, Ismail BA, Zamri M, Mohd Nasir NF. Prevalence of menopausal symptoms, its effect to quality of life among Malaysian women and their treatment seeking behaviour. Med J Malaysia. 2017;72(2):94–9.

Alay I, Kaya C, Cengiz H, Yildiz S, Ekin M, Yasar L. The relation of body mass index, menopausal symptoms, and lipid profile with bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;59(1):61–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjog.2019.11.009.

Blümel JE, Arteaga E, Parra J, Monsalve C, Reyes V, Vallejo MS, et al. Decision-making for the treatment of climacteric symptoms using the menopause rating scale. Maturitas. 2018;111:15–9.

Cengiz H, Kaya C, Suzen Caypinar S, Alay I. The relationship between menopausal symptoms and metabolic syndrome in postmenopausal women. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2019;39(4):529–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443615.2018.1534812.

Chuni N, Sreeramareddy CT. Frequency of symptoms, determinants of severe symptoms, validity of and cut-off score for menopause rating scale (MRS) as a screening tool: a cross-sectional survey among midlife Nepalese women. BMC Womens Health. 2011;11:30.

da Silva AR, d'Andretta Tanaka AC. Factors associated with menopausal symptom severity in middle-aged Brazilian women from the Brazilian Western Amazon. Maturitas. 2013;76(1):64–9.

Dwi Susanti H, Chang PC, Chung MH. Construct validity of the menopause rating scale in Indonesia. Climacteric. 2019;22(5):454–9.

El Shafie K, Al Farsi Y, Al Zadjali N, Al Adawi S, Al Busaidi Z, Al SM. Menopausal symptoms among healthy, middle-aged Omani women as assessed with the menopause rating scale. Menopause. 2011;18(10):1113–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e31821b82ee.

Jaber RM, Khalifeh SF, Bunni F, Diriye MA. Patterns and severity of menopausal symptoms among Jordanian women. J Women Aging. 2017;29(5):428–36.

Kamal NN, Seedhom AE. Quality of life among postmenopausal women in rural Minia, Egypt. East Mediterr Health J. 2017;23(8):527–33. https://doi.org/10.26719/2017.23.8.527.

Kong F, Wang J, Zhang C, Feng X, Zhang L, Zang H. Assessment of sexual activity and menopausal symptoms in middle-aged Chinese women using the menopause rating scale. Climacteric. 2019;22(4):370–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/13697137.2018.1547702.

Kyvernitakis I, Ziller V, Hars O, Bauer M, Kalder M, Hadji P. Prevalence of menopausal symptoms and their influence on adherence in women with breast cancer. Climacteric. 2014;17(3):252–9. https://doi.org/10.3109/13697137.2013.819327.

Lee SW, Jo HH, Kim MR, Kwon DJ, You YO, Kim JH. Association between menopausal symptoms and metabolic syndrome in postmenopausal women. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;285(2):541–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-011-2016-5.

Legorreta D, Montaño JA, Hernández I, Salinas C, Hernández-Bueno JA. Age at menopause, motives for consultation and symptoms reported by 40-59-year-old Mexican women. Climacteric. 2013;16(4):417–25. https://doi.org/10.3109/13697137.2012.696288.

Lena R, Gunilla S, Lena N, Wigren M, Hange D, Gunnarsson R, et al. Prevalence of somatic and urogenital symptoms as well as psychological health in women aged 45 to 55 attending primary health care: a cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2017;17(1):128.

Loja-Chango R, Pérez-López FR, Simoncini T, Escobar GS, Chedraui P. Increased mood symptoms in postmenopausal women related to the polymorphism rs743572 of the CYP17 A1 gene. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2016;32(10):827–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/09513590.2016.1177015.

Looby SE, Shifren J, Corless I, Rope A, Pedersen MC, Joffe H, et al. Increased hot flash severity and related interference in perimenopausal human immunodeficiency virus-infected women. Menopause. 2014;21(4):403–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0b013e31829d4c4c.

Masjoudi M, Amjadi MA, Leyli EKN. Severity and frequency of menopausal symptoms in middle aged women, Rasht, Iran. 2017;11(8):Qc17–J Clin Diagn Res, qc21.

Nisar N, Sikandar R, Sohoo NA. Menopausal symptoms: prevalence, severity and correlation with sociodemographic and reproductive characteristics. A cross sectional community based survey from rural Sindh Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2015;65(4):409–13.

Rathnayake N, Lenora J, Alwis G, Lekamwasam S. Prevalence and severity of menopausal symptoms and the quality of life in middle-aged women: a study from Sri Lanka. Nurs Res Pract. 2019;2019:2081507.

Saccomani S, Lui-Filho JF, Juliato CR, Gabiatti JR, Pedro AO, Costa-Paiva L. Does obesity increase the risk of hot flashes among midlife women?: a population-based study. Menopause. 2017;24(9):1065–70. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000000884.

Sharma S, Mahajan N. Menopausal symptoms and its effect on quality of life in urban versus rural women: a cross-sectional study. J Midlife Health. 2015;6(1):16–20.

Tan MN, Kartal M, Guldal D. The effect of physical activity and body mass index on menopausal symptoms in Turkish women: a cross-sectional study in primary care. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14(1):38. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-14-38.

Thapa R, Yang Y. Menopausal symptoms and related factors among Cambodian women. Women Health. 2020;60(4):396–411.

Topatan S, Yıldız H. Symptoms experienced by women who enter into natural and surgical menopause and their relation to sexual functions. Health Care Women Int. 2012;33(6):525–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2011.646374.

Vural PI, Yangin HB. Assessing menopausal symptoms among Turkish and German women with the menopause rating scale: a cross-cultural study. Int J Caring Sci. 2017;10(2):979–87.

Yisma E, Eshetu N, Ly S, Dessalegn B. Prevalence and severity of menopause symptoms among perimenopausal and postmenopausal women aged 30-49 years in Gulele sub-city of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Womens Health. 2017;17(1):124. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-017-0484-x.

Wu HC, Wen SH, Hwang JS, Huang SC. Validation of the traditional Chinese version of the menopausal rating scale with WHOQOL-BREF. Climacteric. 2015;18(5):750–6. https://doi.org/10.3109/13697137.2015.1044513.

Ojeda E, Monterrosa A, Blümel JE, Escobar-López J, Chedraui P. Severe menopausal symptoms in mid-aged Latin American women can be related to their indigenous ethnic component. Climacteric. 2011;14(1):157–63. https://doi.org/10.3109/13697130903576297.

AlDughaither A, AlMutairy H, AlAteeq M. Menopausal symptoms and quality of life among Saudi women visiting primary care clinics in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Int J Womens Health. 2015;7:645–53.

AlQuaiz AM, Tayel SA, Habiba FA. Assessment of symptoms of menopause and their severity among Saudi women in Riyadh. Ann Saudi Med. 2013;33(1):63–7.

Boral Ş, Borde T, Kentenich H, Wernecke KD, David M. Migration and symptom reporting at menopause: a comparative survey of migrant women from Turkey in Berlin, German women in Berlin, and women in Istanbul. Menopause. 2013;20(2):169–78. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0b013e3182698827.

Abshirini M, Siassi F, Koohdani F, Qorbani M, Khosravi S, Hedayati M, et al. Dietary total antioxidant capacity is inversely related to menopausal symptoms: a cross-sectional study among Iranian postmenopausal women. Nutrition. 2018;55–56:161–7.

Joseph N, Nagaraj K, Saralaya V, Nelliyanil M, Rao PJ. Assessment of menopausal symptoms among women attending various outreach clinics in south Canara District of India. J Midlife Health. 2014;5(2):84–90. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-7800.133996.

Olaolorun FM, Lawoyin TO. Experience of menopausal symptoms by women in an urban community in Ibadan, Nigeria. Menopause. 2009;16(4):822–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e318198d6e7.

Moravcová M, Mareš J, Ježek S. Menopause rating scale - validation Czech version specific instrument for assessing healt-related quality of life in postmenopausal women. Ošetř Porod Asist (Cent Eur J Nurs Midw). 2014;5(1):36–45.

Hickey M, Riach K, Kachouie R, Jack G. No sweat: managing menopausal symptoms at work. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;38(3):202–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/0167482X.2017.1327520.

Rahman S, Salehin F, Iqbal A. Menopausal symptoms assessment among middle age women in Kushtia, Bangladesh. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4(1):188. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-4-188.

Dienye PO, Judah F, Ndukwu G. Frequency of symptoms and health seeking behaviours of menopausal women in an out-patient clinic in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Glob J Health Sci. 2013;5(4):39–47. https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v5n4p39.

Santonicola A, Iovino P, Cappello C, Capone P, Andreozzi P, Ciacci C. From menarche to menopause: the fertile life span of celiac women. Menopause. 2011;18(10):1125–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e3182188421.

Choo SB, Saifulbahri A, Zullkifli SN, Fadzil ML, Redzuan AM, Abdullah N, et al. Adjuvant endocrine therapy side-effects among postmenopausal breast cancer patients in Malaysia. Climacteric. 2019;22(2):175–81.

Chou MF, Wun YT, Pang SM. Menopausal symptoms and the menopausal rating scale among midlife chinese women in Macau, China. Women Health. 2014;54(2):115–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2013.871767.

Gómez-Tabares G, García W, Bedoya-Dorado E, Cantor E. Screening sarcopenia through SARC-F in postmenopausal women: a single-center study from South America. Climacteric. 2019;22(6):627–31.

Rahman SA, Zainudin SR, Mun VL. Assessment of menopausal symptoms using modified menopause rating scale (MRS) among middle age women in Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2010;9(1):5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1447-056X-9-5.

Zhang Y, Zhao X, Leonhart R, Nadig M, Hasenburg A, Wirsching M, et al. A cross-cultural comparison of climacteric symptoms, self-esteem, and perceived social support between Mosuo women and Han Chinese women. Menopause. 2016;23(7):784–91. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000000621.

Waidyasekera H, Wijewardena K, Lindmark G, Naessen T. Menopausal symptoms and quality of life during the menopausal transition in Sri Lankan women. Menopause. 2009;16(1):164–70. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e31817a8abd.

Rathnayake N, Lenora J, Alwis G, Lekamwasam S. Cross cultural adaptation and analysis of psychometric properties of Sinhala version of menopause rating scale. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16(1):161.

Khatoon A, Husain S, Husain S, Hussain S. An overview of menopausal symptoms using the menopause rating scale in a tertiary care center. J Midlife Health. 2018;9(3):150–4. https://doi.org/10.4103/jmh.JMH_31_18.

Gazibara T, Dotlic J, Kovacevic N, Kurtagic I, Nurkovic S, Rancic B, et al. Validation of the menopause rating scale in Serbian language. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;292(6):1379–86.

Budakoğlu II, Ozcan C, Eroğlu D, Yanik F. Quality of life and postmenopausal symptoms among women in a rural district of the capital city of Turkey. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2007;23(7):404–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09513590701444748.

Baral G. Menopause rating scale: validation and applicability in nepalese women. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2019;17(1):9–14. https://doi.org/10.33314/jnhrc.v17i01.1770.

Agaba PA, Meloni ST, Sule HM, Ocheke AN, Agaba EI, Idoko JA, et al. Prevalence and predictors of severe menopause symptoms among HIV-positive and -negative Nigerian women. Int J STD AIDS. 2017;28(13):1325–34.

Wu HC, Chen KH, Hwang JS. Association of menopausal symptoms with different constitutions in climacteric women. Complement Med Res. 2018;25(6):398–405. https://doi.org/10.1159/000491389.

Schneider HP, Rosemeier HP, Schnitker J, Gerbsch S, Turck R. Application and factor analysis of the menopause rating scale [MRS] in a post-marketing surveillance study of Climen. Maturitas. 2000;37(2):113–24.

Neutzling AL, Leite HM, Paniz VMV, de Bairros FS. Dias da Costa JS, Olinto MTA. Association between common mental disorders, sleep quality, and menopausal symptoms: a population-based study in southern Brazil. Menopause. 2020;27(4):463–72. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000001524.

Aparicio VA, Borges-Cosic M, Ruiz-Cabello P, Coll-Risco I, Acosta-Manzano P, Špacírová Z, et al. Association of objectively measured physical activity and physical fitness with menopause symptoms. Flamenco Project Climacteric. 2017;20(5):456–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/13697137.2017.1329289.

Canário AC, Cabral PU, Spyrides MH, Giraldo PC, Eleutério J Jr, Gonçalves AK. The impact of physical activity on menopausal symptoms in middle-aged women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;118(1):34–6.

Liu P, Yuan Y, Liu M, Wang Y, Li X, Yang M, et al. Factors associated with menopausal symptoms among middle-aged registered nurses in Beijing. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2015;31(2):119–24. https://doi.org/10.3109/09513590.2014.971237.

Ruan X, Cui Y, Du J, Jin F, Mueck AO. Prevalence of climacteric symptoms comparing perimenopausal and postmenopausal Chinese women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;38(3):161–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/0167482X.2016.1244181.

Slopien R, Owecki M, Slopien A, Bala G, Meczekalski B. Climacteric symptoms are related to thyroid status in euthyroid menopausal women. J Endocrinol Investig. 2020;43(1):75–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-019-01078-7.

Zhao G, Wang L, Yan R, Dennerstein L. Menopausal symptoms: experience of Chinese women. Climacteric. 2000;3(2):135–44. https://doi.org/10.3109/13697130009167615.

Luptáková L, Sivaková D, Srámeková D, Cvícelová M. The association of cytochrome P450 1B1 Leu432Val polymorphism with biological markers of health and menopausal symptoms in Slovak midlife women. Menopause. 2012;19(2):216–24. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e3182281b54.

Luptáková L, Sivtáková D, Cernanová V, Cvicelová M. Menopausal complaints in Slovak midlife women and the impact of CYP1B1 polymorphism on their incidence. Anthropol Anz. 2012;69(4):399–415. https://doi.org/10.1127/0003-5548/2012/0217.

Ishizuka B, Kudo Y, Tango T. Cross-sectional community survey of menopause symptoms among Japanese women. Maturitas. 2008;61(3):260–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.07.006.

Oi N, Ohi K. Comparison of the symptoms of menopause and symptoms of thyroid disease in Japanese women aged 35-59 years. Climacteric. 2013;16(5):555–60. https://doi.org/10.3109/13697137.2012.717995.

Im E-O, Ham OK, Chee E, Chee W. Racial/ethnic differences in cardiovascular symptoms in four major racial/ethnic groups of midlife women: a secondary analysis. Women Health. 2015;55(5):525–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2015.1022813.

Bashar M, Ahmed K, Uddin MS, Ahmed F, Emran AA, Chakraborty A. Depression and quality of life among postmenopausal women in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. J Menopausal Med. 2017;23(3):172–81.

Lyndaker C, Hulton L. The influence of age on symptoms of perimenopause. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2004;33(3):340–7.

Dotlic J, Kurtagic I, Nurkovic S, Kovacevic N, Radovanovic S, Rancic B, et al. Factors associated with general and health-related quality of life in menopausal transition among women from Serbia. Women Health. 2018;58(3):278–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2017.1306604.

Schnatz PF, Serra J, O'Sullivan DM, Sorosky JI. Menopausal symptoms in Hispanic women and the role of socioeconomic factors. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2006;61(3):187–214. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ogx.0000201923.84932.90.

Huseth-Zosel A, Strand M, Perry J. Socioeconomic differences in the menopausal experience of Chinese women. Post Reprod Health. 2014;20(3):98–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053369114544729.

Inayat K, Danish N, Hassan L. Symptoms of menopause in peri and postmenopausal women and their attitude towards them. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2017;29(3):477–80.

Sukwatana P, Meekhangvan J, Tamrongterakul T, Tanapat Y, Asavarait S, Boonjitrpimon P. Menopausal symptoms among Thai women in Bangkok. Maturitas. 1991;13(3):217–28.

Biri A, Bakar C, Maral I, Karabacak O, Bumin MA. Women with and without menopause over age of 40 in Turkey: consequences and treatment options. Maturitas. 2005;50(3):167–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2004.05.013.

Chen R, Chang T, Chow S. Perceptions of and attitudes toward estrogen therapy among surgically menopausal women in Taiwan. Menopause. 2008;15(3):517–23. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e3181591dc9.

Pan HA, Wu MH, Hsu CC, Yao BL, Huang KE. The perception of menopause among women in Taiwan. Maturitas. 2002;41(4):269–74.

McKinlay SM, Jefferys M. The menopausal syndrome. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1974;28(2):108–15. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.28.2.108.

Hartmann BW, Kirchengast S, Albrecht A, Metka M, Huber JC. Hysterectomy increases the symptomatology of postmenopausal syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1995;9(3):247–52.

Wolff EF, He Y, Black DM, Brinton EA, Budoff MJ, Cedars MI, et al. Self-reported menopausal symptoms, coronary artery calcification, and carotid intima-media thickness in recently menopausal women screened for the Kronos early estrogen prevention study (KEEPS). Fertil Steril. 2013;99(5):1385–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.11.053.

Peng W, Sibbritt DW, Hickman L, Adams J. Association between use of self-prescribed complementary and alternative medicine and menopause-related symptoms: a cross-sectional study. Complement Ther Med. 2015;23(5):666–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2015.07.004.

Somekawa Y, Chiguchi M, Ishibashi T, Aso T. Soy intake related to menopausal symptoms, serum lipids, and bone mineral density in postmenopausal Japanese women. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(1):109–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0029-7844(00)01080-2.

Asplund R, Aberg HE. Nightmares, cardiac symptoms and the menopause. Climacteric. 2003;6(4):314–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/cmt.6.4.314.320.

Gazibara T, Nurkovic S, Kovacevic N, Kurtagic I, Rancic B, Radovanovic S, et al. Factors associated with sexual quality of life among midlife women in Serbia. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(10):2793–804. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1608-3.

Michel JL, Mahady GB, Veliz M, Soejarto DD, Caceres A. Symptoms, attitudes and treatment choices surrounding menopause among the Q'eqchi Maya of Livingston, Guatemala. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(3):732–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.02.010.

Otolorin EO, Adeyefa I, Osotimehin BO, Fatinikun T, Ojengbede O, Otubu JO, et al. Clinical, hormonal and biochemical features of menopausal women in Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr J Med Med Sci. 1989;18(4):251–5.

Obermeyer CM, Reynolds RF, Price K, Abraham A. Therapeutic decisions for menopause: results of the DAMES project in Central Massachusetts. Menopause. 2004;11(4):456–65. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.GME.0000109318.11228.DA.

Conde DM, Pinto-Neto AM, Santos-Sá D, Costa-Paiva L, Martinez EZ. Factors associated with quality of life in a cohort of postmenopausal women. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2006;22(8):441–6.

Holte A. Influences of natural menopause on health complaints: a prospective study of healthy Norwegian women. Maturitas. 1992;14(2):127–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-5122(92)90005-O.

Ferreira CE, Pinto-Neto AM, Conde DM, Costa-Paiva L, Morais SS, Magalhães J. Menopause symptoms in women infected with HIV: prevalence and associated factors. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2007;23(4):198–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/09513590701253743.

Gold EB, Sternfeld B, Kelsey JL, Brown C, Mouton C, Reame N, et al. Relation of demographic and lifestyle factors to symptoms in a multi-racial/ethnic population of women 40-55 years of age. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(5):463–73. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/152.5.463.

Tandon VR, Mahajan A, Sharma S, Sharma A. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in postmenopausal women: a rural study. J Midlife Health. 2010;1(1):26–9.

Blell MT. Menopausal symptoms among British Pakistani women: a critique of the standard checklist approach. Menopause. 2015;22(1):79–87.

Kirchengast S. Relations between fertility, body shape and menopause in Austrian women. J Biosoc Sci. 1992;24(4):555–9.

Kirchengast S. Relations between anthropometric characteristics and degree of severity of the climacteric syndrome in Austrian women. Maturitas. 1993;17(3):167–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-5122(93)90044-I.

Kimberlin CL, Winterstein AG. Validity and reliability of measurement instruments used in research. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(23):2276–84. https://doi.org/10.2146/ajhp070364.

MRS - the menopause rating scale developed by the Berlin Center for Epidemiology and Health Research 2013 [Available from: http://www.menopause-rating-scale.info/. Accessed 20 Nov 2020.

Heinemann LAJ, Potthoff P, Schneider HPG. International versions of the Menopause Rating Scale (MRS). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:28.

Kirkova J, Davis MP, Walsh D, Tiernan E, O'Leary N, LeGrand SB, et al. Cancer symptom sssessment instruments: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(9):1459–73. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.02.8332.

Whitehead L. The measurement of fatigue in chronic illness: a systematic review of unidimensional and multidimensional fatigue measures. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2009;37(1):107–28.

Pettersson G, Berterö C, Unosson M, Börjeson S. Symptom prevalence, frequency, severity, and distress during chemotherapy for patients with colorectal cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(5):1171–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-2069-z.

Sidani S. Principles of outcome measurement and analyses. In: Carmichael M, Seaman J, editors. Heath intervention research: understanding research design and method. London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2015. p. 197–211. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473910140.n12.

Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, Rothrock N, Reeve B, Yount S, et al. The patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(11):1179–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011.

Obermeyer CM, Reher D, Saliba M. Symptoms, menopause status, and country differences: a comparative analysis from DAMES. Menopause. 2007;14(4):788–97. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e318046eb4a.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This publication was made possible with support of the Indiana University Ethel Clarke Fellowship and a Collaboration in Translational Research Pilot Grant (Carpenter/Tisdale MPI) from the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute funded, in part by Grant Number UL1TR002529 from the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Clinical and Translational Sciences Award. Dr. Sheng is supported as a postdoctoral fellow under 5T32CA117865 (V. Champion, PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JSC and JET originated the idea for this manuscript and secured funding. CAP conducted the electronic database searches in collaboration with JSC. JSC, CDE, and JSA performed article title and abstract screening, review of full-texts, and data extraction. YS and MY completed additional quality checks on data extraction. YS and JSC drafted the manuscript text and tables. All authors provided critical input into the draft and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

JSC reports personal fees from RoundGlass Inc., personal fees from Astellas Pharma Inc., personal fees from Kappa Santé, personal fees from Sojournix, and other from QUE oncology. YS, CDE, JSA, MY, CAP, CXC, and JET declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Sheng, Y., Carpenter, J.S., Elomba, C.D. et al. Review of menopausal palpitations measures. womens midlife health 7, 5 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40695-021-00063-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40695-021-00063-6