Abstract

Background

Photosynthetic characteristics and the effect of UV radiation and elevated temperature measured were studied in Chlorella sp. isolated from a snow microalgal community at King George Island, Maritime Antarctica through the chlorophyll florescence (rapid light curves and maximum quantum yield, respectively). The environmental context was monitored through measurements of spectral depth profiles of solar radiation (down to 40 cm) in the snowpack as well as a through continuous recording of temperature and PAR using dataloggers located at different depths (0–30 cm) within the snow column.

Results

The photochemistry of Chlorella sp. was affected by UV radiation in a 12-h laboratory exposure under all studied temperatures (5, 10, 15, 20 °C): the algae exposed to PAR + UV-A radiation were inhibited by 5.8 % whilst PAR + UV-A + UV-B radiation decreased Fv/Fm by 15.8 %. In both treatments the 12-h recovery after UV exposure was almost complete (80–100 %). Electron transport based P-I curve parameters maximal electron transport rate (ETRmax), photosynthetic efficiency (α) and the saturating irradiance (Ek) no varied in response to different temperatures.

Conclusions

Results revealed that Chlorella sp. not only shows high photosynthetic efficiency at ambient conditions, but also exhibits tolerance to solar radiation under higher temperatures and possessing a capacity for recovery after inhibition of photosynthesis by UV radiation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The Antarctic cryosphere represents a hostile habitat for life, characterized by extreme temperature conditions varying abruptly between freezing and melting points, high levels of solar radiation, especially harmful wavelengths of ultraviolet (UV) radiation, nutrient limitation, changes in pH and osmotic stress [1, 2]. The physico-chemical properties of melting snow allow psychrophilic algae to grow in liquid interstices, where the temperature is just above the freezing point [3–5]. In polar snowfields, the biomass of snow algae can become very important and due to their capacity to fix and store carbon they play a key role as primary producers in the biogeochemical cycles in Arctic and Antarctic regions [6]. In coastal areas of West Antarctic Peninsula and adjacent islands, an eco-region denominated Maritime Antarctica, processes occurring in glacier and snow ecosystems are closely interrelated with those of the marine realm. Melting of massive snow/ice accumulations and consequent run-off have strong impact on the physical and biological processes of near-shore pelagic and benthic communities [7, 8].

Due to that snow algae inhabit ecosystems highly sensitive and responsive to shifts in environmental conditions (e.g. temperature, light and precipitation), they can be regarded as excellent model organisms to examine the impact of climate change. Warming in several regions has been related with lower precipitation as snow, earlier runoff and hence, a shortened period of snow permanence [9, 10]. Under these scenarios, snow algae and their associated microbial community have to adapt to new regimes of melting and freezing [11], underlining not well-understood physiological adaptations.

Unlike alpine and other continental snowfields, coastal snow packs located in Maritime Antarctica are tentatively eutrophic environments, mostly due to the presence of seabird and mammal colonies [12]. Thus, for this habitat, light and temperature remain as the major stressors for snow algae. However, the question how these factors, alone or in combination, impact snow communities in Antarctic coastal snowfields has been poorly addressed. Data from alpine snow algae indicate that light, especially due to scattering, can be elevated and thus, algae have to cope with irradiation stress, caused by Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR) and Ultraviolet (UV) in conditions of low temperatures. Especially during the sensitive motile green phase in their life cycle, microalgae are sensitive excess PAR and UV [13], which affect different molecules and processes (e.g. DNA, photosynthetic apparatus, lipid membranes, etc.; reviewed by [14]) and also cell motility [15]. However, some snow algae downregulate their photochemical processes via a series of dissipative mechanisms such as the violaxanthin cycle, synthesis and accumulation of astaxanthin, turnover of D1 proteins, antenna quenching, cold induced transcripts and cold-adapted proteins, etc. which operate at temperatures close to 0 °C [12, 16, 17]. The question whether these mechanisms operate efficiently at higher temperatures remains open.

Chlorella is a unicellular green alga, which has a single chloroplast, rigid cell wall and lacks flagella [18]. The genus is globally distributed including the Antarctic [19, 20]. In general this microalga inhabits soils and other ice-free environments, however, can also be found in snow packs during the summer melting season [21]. Teoh et al. [22] analysed the growth rates, biochemical composition and profile of fatty acids of six Antarctic strains, of which algae of the class Trebouxiophyceae, including Chlorella, presented the greatest growth rates at enhanced temperature of 20 °C. Significant alterations in the morphology and activity of the chloroplasts in response to enhanced UV-B radiation have been reported for this genus [23]. Due to that gradients in solar radiation along the snowpack can impose not only considerable stress as a consequence of detrimental and photoinhibitory levels of UV radiation and PAR, but also can result in light limitation for photosynthesis at lower snow depths, one could argue that an acclimation process or physiological flexibility are important to ensure primary production. Up to now, most of the studies on snow algal photobiology have been conducted in ubiquitous flagellate green algal genera such as Chlamydomonas, or Chloromonas, which show an ability to actively migrate along the snow pack column and thus “regulate” their light environment [3, 24–26]. In a recent study was demonstrated that Antarctic strains of Chlorella are more sensitive to UV radiation under elevated temperature than their counterparts from temperate or tropical regions [27]. Thus, in the present study the question whether photosynthetic characteristics of non-motile Chlorella sp. isolated from snow fields in Maritime Antarctica (King George Island) match the light and temperature conditions prevailing at different snow depths was examined. Moreover, the ability of Chlorella to endure environmental stress was assessed in a series of controlled exposures to UV radiation and elevated temperature. The prediction that elevated temperatures will enhance the detrimental effects of UV radiation was tested.

Methods

Collection and isolation of snow microalgae

During February 2015, snow samples with evident presence of snow algae (green coloration) were collected at depths below 10 cm (vegetative cells) at Elefantera beach, Fildes Peninsula King George Island (62°11'57,07'' S; 58°59'42,48''W). Samples were transported to the laboratory in the station “Base Profesor Julio Escudero” where they were cultured in bottles (TR6000, TrueLine, USA) using “Snow Algae” media standardized according to protocols defined by the culture Collection of algae of The University of Texas at Austin (UTEX). The samples were kept at a temperature of 5 °C with a photoperiod of 18:6 D:L, at irradiance of 4.7 μmol m-2 s-1. The samples were transferred to the Photobiology Laboratory of the Universidad Austral de Chile, in Valdivia, where Chlorella sp. was isolated by successive dilutions and repeated subcultures [28]. The clonal stock culture (now coded as ChlaP7MSA) was kept at a temperature of 5 °C under a 12:12 L:D light regime at 4.7 μmol m-2 s-1. These culture conditions were maintained to achieve the exponential growth phase, determined through daily cell counts, with an optical microscope using a Neubauer chamber. Cultures were photographed under Olympus BX51TF epifluorescence microscope (model CKX41SF; Olympus, Japan) equipped with a digital camera (QImaging Micro Plublisher 5.0 RTV; software QCapture pro) under bright-field as well as visualizing chlorophyll as orange-red autofluorescence according to the methodology described by Huovinen and Gómez [29] with the U-MWBV2 mirror unit (Olympus) (excitation 400–440 nm, detection of emission from 475 nm) (Fig. 1). Experiments were performed with the clonal stock culture in the exponential growth phase.

Field collection samples and light microscopy of dividing cells of Chlorella sp. (exponential growth phase). Sampling (a), thawed samples on darkness (b). Living cells were observed under bright field (c) and blue-violet light showing red autofluorescence of chlorophyll (d). The photograph shows two cells after division (e). Autospore maturing phase with four daughter cells (f-a) and release of cells (f-b). Scale = 5 μm

Measurement of solar radiation and temperature in the snowpack

In situ spectral irradiance was measured during a sunny day (February 13, 2015 at noon) using an underwater hyperspectral radiometer (RAMSES-ACC2-UV–Vis, TriOs Optical Sensors, Rastede, Germany) through the snow column down to a depth of 40 cm (8 and 19 measurements per depth). According to the President Eduardo Frei Montalva Metereological Station’s records, this day had 10 % cloud cover, and moderate breeze from the Northwest at 3 m/s. At the same time, a set of HOBO UA-002-64 dataloggers (Onset Computer Corporation, Bourne, MA, USA) was programmed to record temperature and solar irradiance (PAR) at 0, 10, 20 and 30 cm depth in the snow column every 5 min for 15 days during the study period.

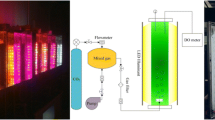

Exposures to temperature and UV radiation

Samples from Chlorella sp. clonal culture (3500 cell/ml, exponential growth phase) were put in cell culture plates without aeration and exposed to PAR, PAR + UV-A and PAR + UV-A + UV-B radiation treatments for 12 h under a 4 temperature conditions (5, 10, 15 and 20 °C), followed by a 12-h recovery period in dim light without UV. A thermoregulated waterbath (Digit-Cool, Selecta, Spain) was used to set the different temperatures, whilst illumination was provided by three types of fluorescent lamps: UV-B-313 emitting UV-B; UV-A-340 emitting UV-A (Q-Panel, USA) and and TL-D 36 W/54-765 emitting PAR (Philips, Thailand). Three UV treatments were obtained by covering the cell culture with different cut-off filters: Ultraphan 295 (Digefra, Germany) for PAR + UV-A + UV-B condition, Ultraphan 320 for PAR + UV-A, and Ultraphan 400, for PAR treatment. The experimental UV irradiances were set at 0.25 W m-2 for UV-B and 0.95 W m-2 for UV-A, whilst the PAR irradiance was of 10 μmol m-2 s-1. Total radiation dose during the 12 h exposure was 10.8 kJ m-2 for UV-B and 40.5 kJ m-2 for UV-A. The radiation levels were measured using the RAMSES-ACC2-UV–Vis hyperspectral radiometer.

Chlorophyll fluorescence measurements

The photosynthetic performance of Chlorella was measured before and after exposure to different temperatures and radiation treatments using an amplitude modulation fluorometer (Water PAM, Walz, Effeltrich, Germany). After a 12-h exposure, as well as after a 12-h recovery period, the samples were kept for 10 min in darkness and the maximum quantum yield (Fv/Fm) was subsequently measured.

The P-I curves were based on electron transport rate vs. irradiance (ETR-I) curves by exposing the Chlorella samples to a gradient of PAR irradiances (0 to 446 μmol photon m–2 s–1) under the four temperatures described above. The relative electron transport rate (rETR) was estimated relating the effective quantum yield (ΦPSII) and the intensity of actinic radiation [30], as follows:

where EPAR is the incident actinic irradiance. The 0.5 factor comes from the assumption that 4 of the 8 electrons required to assimilate one CO2 molecule are provided by the PSII. The ETR parameters were defined through a modified non-linear function proposed by Jassby and Platt [31]:

where rETRmax is the maximum electron transport rate, tanh is the hyperbolic tangent function, α is the efficiency of electron transport (initial slope of the rETR vs. irradiance curves), and E is the incident irradiance. The saturation irradiance for electron transport (Ek) was calculated as the intersection between α and the rETRmax values.

The effect of UV radiation and temperature was assessed by comparing the inhibition of Fv/Fm, that was calculated as the percentage of decrease between the values measured in PAR + UV-A and PAR + UV-A + UV-B and values measured in samples exposed only to PAR. Likewise, the recovery was estimated by comparing the Fv/Fm values of the samples treated with UV radiation with those treated only with PAR.

Statistical analysis

The variation in the incident solar radiation of UV-B, UV-A and PAR at different depths (0, 10, 20, 30, 40 cm) was compared using nonparametric analysis of variance (Kruskal-Wallis). The variation in the responses of the photosynthetic parameters to the UV radiation exposure and recovery at different temperatures, were compared through a two-way variance analysis (ANOVA). Post-hoc comparisons were carried out using Tukey HSD test. In both analyses, the ANOVA assumptions (variance homogeneity, normal distribution) were examined through the Levene’s and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests, respectively.

Results

In situ solar irradiance and temperature

The weather conditions at King George Island during the study period was characterized by cloudy days. In this line, maximal PAR values normally did not exceed 400 μmol m–2 s–1 (Table 1). For a sunny day (10 % could cover), the daily course of solar irradiation and temperature measured at 0, 10, 20 and 30 cm depths in the snow column is shown in Fig. 2. The surface irradiance reached values of 1300 μmol m–2 s–1 around midday and was attenuated by 70 % at 10 cm (decreasing to less than 350 μmol m–2 s–1). This value matches the light requirements for saturation of photosynthesis (Ek) measured for Chlorella sp. (see Table 1). The number of hours at which algae remain under saturating irradiance (Hsat) at the surface was close to 12-13 h, decreasing with increasing depth (Fig. 2a). Temperature in the snow pack varied within the ranges of minimum and maximum air temperature registered by the Presidente Eduardo Frei Meteorological Station (Fig. 2b). Maximal temperature at 10 cm depth was close to 4 °C with a positive correlation between the solar irradiation and the temperature at each depth (r > 0.9; p < 0.05). Under 10 cm, temperature was close to 2 °C and varied less in the course of the day. The spectral profiles of UV radiation and PAR indicated strong decreases of UV-A and UV-B below 10 cm depth (Fig. 2c; Table 2).

February 13 daily cycle of PAR (a), temperature (b) and spectral light penetration (c) in the snow column at King George Island, Maritime Antarctica. The dotted line (a) indicates saturating irradiance level for photosynthesis in Chlorella sp. (Ek = 276 μmol photons m–2 s–1). The maximum (4,3 °C) and minimum (-1,4 °C) air temperature is presented (b)

Photosynthetic responses

The ETR-I curves indicated lower photosynthesis in samples incubated to 5 °C compared to higher temperatures (Fig. 3, Table 3). Mean values of ETRmax ranged between 50.6 at 5 °C and 71.6 at 10 °C. Similarly, the light requirements for photosynthesis (Ek) were lower in algae incubated to 5 °C (204.7 μmol e- m-2 s-1) compared to the other temperatures where Ek varied between 259 and 276 μmol e- m-2 s-1 (Table 3). The initial slope (α) did not varied between temperature treatments (Table 3).

The exposure to UV radiation caused Fv/Fm inhibition in Chlorella sp. (Fig. 4; p < 0.001; ANOVA; Table 4;). PAR + UV-A radiation was responsible for 5.8 % inhibition, but when UV-B was added (PAR + UV-A + UV-B) Fv/Fm decreased by 15.8 %. The temperature factor did not promote Fv/Fm differences. After the period of darkness, the Fv/Fm recovery varied between 80 to 100 %, with an increase in the recovery level associated to an increase in temperature (Fig. 4; p < 0.001; ANOVA; Table 4).

Discussion

Photosynthetic characteristics and the light environment

Our results show that at the sampling location in Fildes Peninsula, 10 cm below the snow surface irradiance does not exceed 350 μmol m–2 s–1, which matches well the average light required for saturation of photosynthesis determined in this study for Chlorella sp. (276 μmol m–2 s–1). Using the number of hours per day at which algae are exposed to saturating irradiances (the so-called Hsat), one can argue that photosynthesis of these microalga is not limited by at least for 10 h at a depth of 10 cm and 12–13 h at the surface of the snowpack, during sunny conditions. In general, these light requirements are in the lower ranges described for Chlamydomonas from Giant Mountains, Czech Republic [25] and clearly lower than light requirements of 523–826 μmol photons m–2 s–1 measured in an Arctic population of Chlamydomonas nivalis [32]. In contrast to Chlorella sp., the high Ek values determined in Chlamydomonas are indicative of that these algae are exposed to photoinhibitory levels of PAR, which could have negative effects on photosynthesis. In fact, it is well documented in this genus that excess of irradiation results in the formation of robust, red pigmented cysts [33–35], which are also mostly located at the surface of the snowpack [36]. Although we did not perform in situ measurements of photosynthesis, the high levels of solar radiation recorded during midday in a sunny day at Fildes Peninsula (exceeding 1200 μmol photons m–2 s–1) suggest that Chlorella can suffer considerable photoinhibition of photosynthesis, at least when exposed to high irradiances close to the snow surface. This is exacerbated by snow reflecting most of the long wavelength radiation [37], directly affecting the light extinction patterns, mostly due to the changes in phase transitions of water [38]. It must be emphasized that in our laboratory study, levels of PAR used in the incubations were considerably lower than current irradiances measured in the field (PAR was maintained low to avoid photoinhibition and mask UV effects) and thus we cannot evaluate the impact of high PAR on the physiology of this alga.

Effects of temperature on UV stress tolerance

Due to its ubiquitous character, many species of Chlorella have been described as eurythermal microorganisms, which can inhabit all type of freshwater and soil environments [22]. This capacity to cope with different thermal conditions has also been recognized for isolated strains of Chlorella sp. from Antarctic [19]. In our study, Chlorella sp. was visually more abundant below 10 cm where temperatures along the day ranged between 0 and 3.8 °C. Apparently, in this environment, algae find a more stable microhabitat with lesser temperature variations [39]. This allows us to argue that excess UV radiation at strata close to the surface would be the key factor limiting the proliferation of Chlorella sp. at depths < 10 cm. In fact, our results indicate that Chlorella sp. is sensitive to UV radiation but not to temperature. Regarding the levels of UV radiation recorded at depths below 10 cm (0.01 W m-2 for UV-B and 1.3 W m-2 for UV-A), it could be argued that microalgae were not exposed to detrimental UV conditions. For example, in situ measurements carried out in the snowfields of the Rocky Mountains, Wyoming, with abundant populations of Chlamydomonas nivalis indicated that maximal transmittance of UV-B radiation was close to 4 cm [24].

The inhibition of the maximum quantum yield (Fv/Fm) of Chlorella sp. was wavelength dependent. Under PAR + UV-A + UV-B treatment, fluorescence values decreased by 15 % after exposures of 5 to 20 °C. For the PAR + UV-A treatment, inhibition of Fv/Fm did not exceed 7 %. However, the recovery of the samples exposed to PAR + UV-A was in the range of 90–100 % relative to PAR control, while recovery in algae exposed to PAR + UV-A + UV-B varied between 80 and 95 %. These results highlight the tolerance of Chlorella to the UV exposure, at least for periods close to 12 h and high UV-B:UV-A ratio. Studies carried out with UMACC 237, another Antarctic Chlorella strain, revealed a higher tolerance to UV-B compared to strains of the same genus isolated from temperate and tropical regions [40]. Apparently, exposure to enhanced UV radiation in snow living populations of Chlorella stimulates the activity of antioxidant enzymes, such as catalases and superoxide dismutase [23, 41] or enhance the synthesis of protective compounds like secondary carotenoids (e.g. in Chlorella zofingiensis) or mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs) [14]. However, when algae were exposed to higher temperatures, repair processes in Antarctic strains increase significantly [27]. This could be a confirmation that elevated temperatures can ameliorate the detrimental impact of UV radiation as has been reported in Antarctic macroalgae [42].

Implications for snow algal ecology in scenarios of climate change

Recent reviews dealing with the ecology of snow algae and in general of extreme cold-adapted organisms [2, 21] emphasize the urgent need for physiological and molecular studies that allow identifying the adaptive and acclimative strategies that snow algae exhibit in response to environmental factors beyond their tolerance threshold. Based on a scenario of extended melt periods in maritime Antarctica [43] with concomitant higher impact of elevated temperature and UV radiation, the examination of stress tolerance mechanisms is essential to understand and predict near-future impacts of climate change especially in polar regions where snowfields and their algal communities have an important role on the biogeochemical fluxes [44]. Snow algae are probably the most sensitive biological indicators of present and future scenarios of regional warming and meltdown in vast sectors of Antarctica, especially at ecologically relevant (seasonal and interannual) scales. In addition to their important role as primary producers, polar extremophiles are involved in exchange of reactive gases with the atmosphere (e.g. N2, CO2, dimethyl sulfoxide, etc.) [2, 45] and in snowfields in the maritime Antarctica, they play important subsidiary roles through the melting runoff, food web and degradation products [7, 8]. The impact that these processes will have on in the biogeochemical cycles of the whole coastal system in this region is unknown and prompt for further research.

Conclusions

Overall, our findings revealed that Chlorella sp. isolated from a snow microalgal community in maritime Antarctic not only shows high photosynthetic efficiency at ambient conditions, but also exhibits tolerance to solar radiation under higher temperatures. Avoiding the highly UV exposed snow surface and possessing a capacity for recovery after inhibition of photosynthesis by UV radiation appear as two important strategies of Chlorella sp. in these ecosystem . However, it remains open how these algae will endure the future Antarctic summer, characterized by warmer temperatures and less snow, in which they will exposed to high solar radiation.

References

Hoham R, Laursen A, Clive S, Duval B (1993). Snow algae and other microbes in several alpine areas in New England. Proceedings of the 50 annual Eastern snow conference, pp. 165 – 173

Laybourn-Parry J, Tranter M, Hodson A (2012) The Ecology of Snow and Ice Enviroments. Oxford University Press Inc., United States

Hoham R, Duval B (2001) Microbial ecology of snow and freshwater ice with emphasis on snow algae. In: Jones H, Pomeroy J, Walker D, Hoham R (eds) Snow Ecology: An Interdisciplinary Examination of Snow-Covered Ecosystems. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 168–228

Komárek J, Nedbalová L (2007) Green Cryosestic Algae. In: Seckbach J (ed) Algae and cyanobacteria in extreme environments. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 321–342

Nagashima H, Matsumoto GI, Ohtani S, Momose H (1995) Temperature acclimation and fatty acid composition of an Antarctic Chlorella. Proc NIPR Symp Polar Biol 8:194–199

Hodson A, Cameron K, Bøggild C, Irvine-Fynn T, Langford H, Pearce D, Banwart S (2010) The structure, biological activity and biogeochemistry of cryoconite aggregates upon an Arctic valley glacier: Longyearbreen. Svalbard J Glaciol 56:349–362

Ducklow H, Clarke A, Dickhut R, Doney SC, Geisz HN, Huang K, Martinson DG, Meredith MP, Moeller HP, Montes-Hugo M, and others. (2012). The marine ecosystem of the West Antarctic Peninsula. Pp. 121–159 in Antarctica: An Extreme Environment in a Changing World. A. Rogers, N. Johnston, A. Clarke, and E. Murphy, eds, Blackwell.

Vogt S, Braun M (2004) Influence of glaciers and snow cover on terrestrial and marine ecosystems as revealed by remotely-sensed data. Revista de Pesquisa Antartica Brasileira 4:105–118

Barnett T, Pierce D, Hidalgo H (2008) Human-induced changes in the hydrology of the western United States. Science 319(5866):1080–1083

Déry SJ, Brown RD (2007) Recent northern hemisphere snow cover extent trends and implications for the snow-albedo feedback. Geophys Res Lett 34(22):L22504. doi:10.1029/2007GL031474

Dove D, Polyakb L, Coakley B (2012) Widespread, multi-source glacial erosion on the Chukchi margin, Arctic Ocean. Quat Sci Rev 92(2014):112e122

Bidigare RR, Ondrusek ME, Kennicutt MC, Iturriaga R, Harvey HR, Hoham RW, Macko SA (1993) Evidence for a photoprotective function for secondary carotenoids of snow algae. J Phycol 29:427–434

Remias, D (2012) Cell structure and physiology of alpine snow and ice algae. In: Lütz, C. (Editor) Plants in alpine regions. Cell physiology of adaption and survival strategies. Springer Wien, 202 p., pp. 175-186. ISBN 978-3-7091-0135-3

Karsten U, Wulff A, Roleda MY, Müller R, Steinhoff FS, Freder-sdorf J, Wiencke C (2009) Physiological responses of polar benthic algae to ultraviolet radiation. Bot Mar 52:639–654

Häder DP, Jori G (2001) Photomovement. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 169–183

Leya T (2013) Snow algae: Adaptation Strategies to Survive on Snow and Ice. In: Seckbach J et al (eds) Polyextremophiles: Life Under Multiple Forms of Stress, vol 27, Cellular Origin, Life in Extreme Habitats and Astrobiology., pp 401–423. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-6488-0_17

Morgan-Kiss RM, Priscu JP, Pocock T, Gudynaite-Savitch L, Hüner NPA (2006) Adaptation and acclimation of photosynthetic microorganisms to permanently cold environments. Microbiol Molec Biol Rev 70:222–252

Eckardt N (2010) The Chlorella genome: big surprises from a small package. Plant Cell 22:2924

Chong GL, Chu WL, Othman RY, Phang SM (2011) Differential gene expression of an Antarctic Chlorella in response to temperature stress. Polar Biol 34:637–645. doi:10.1007/s00300-010-0918-5

Hu H, Li H, Xu X (2008) Alternative cold response modes in Chlorella (Chlorophyta, Trebouxiophyceae) from the Antarctic. Phycologia 47:28–34

Seckbach J (2007) Algae and Cyanobacteria in Extreme Environments (Cellular Origin, Life in Extreme Habitats and Astrobiology). Springer, Dordrecht

Teoh ML, Chu WL, Marchant H, Phang SM (2004) Influence of culture temperature on the growth, biochemical composition and fatty acid profiles of six Antarctic microalgae. J Appl Phycol 16:421–430. doi:10.1007/s10811-005-5502-y

Malanga G, Puntarulo S (1995) Oxidative stress and antioxidant content in Chlorella vulgaris after exposure to ultraviolet-B radiation. Physiolgia Plantarum 94:672–679

Gorton HL, Williams WE, Vogelmann TC (2001) The light environment and cellular optics of the snow alga Chlamydomonas nivalis (Bauer) Wille. Photochem Photobiol 73:611–620, and the rise of continental spring temperatures. Science, 263: 198–200

Kvíderová J (2010) Characterization of the community of Snow Algae and their photochemical performance in situ in the Giant Mountains, Czech Republic. Arct Antarct Alp Res 42(2):210–218

Leya T, Rahn A, Lütz C, Remias D (2009) Response of arctic snow and permafrost algae to high light and nitrogen stress by changes in pigment composition and applied aspects for biotechnology. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 67:432–443

Wong CY, Teoh ML, Phang S-M, Lim P-E, Beardall J (2015) Interactive effects of temperature and UV radiation on photosynthesis of Chlorella strains from polar, temperate and tropical environments: differential impacts on damage and repair. PLoS ONE 10(10):e0139469. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0139469

Andersen R, Kawachi M (2005) Traditional microalgae isolation techniques. In: Andersen RA (ed) Algal culturing techniques. Academic, New York, pp 83–100

Huovinen P, Gómez I (2015) UV sensitivity of vegetative and reproductive tissues of two Antarctic Brown Algae is related to differential allocation of phenolic substances. Photochem Photobiol 2015(91):1382–1388

Schreiber U, Bilger W, Neubauer C (1994) Chlorophyll fluorescence as a non-intrusive indicator for rapid assessment of in vivo photosynthesis. Ecol Stud 100:49–70

Jassby AD, Platt T (1976) Mathematical formulation of the relationship between photosynthesis and light for phytoplankton. Limnol Oceonogr 21:540–547

Stibal M, Elster J, Sabacká M, Kastovská K (2007) Seasonal and diel changes in photosynthetic activity of the snow alga Chlamydomonas nivalis (Chlorophyceae) from Svalbard determined by pulse amplitude modulation fluorometry. Microbiol Ecol 59:265–273

Muller T, Bleiss W, Martin CD, Rogaschewski S, Fuhr G (1998) Snow algae from northwest Svalbard: their identification, distribution, pigment and nutrient content. Polar Biol 20:14–32

Remias D, Lütz C (2007) Characterisation of esterified secondary carotenoids and of their isomers in green algae: a HPLC approach. Algol Stud 124:85–94

Remias D, Wastian H, Lütz C, Leya T (2013) Insights into the biology and phylogeny of Chloromonas polyptera (Chlorophyta), an alga causing orange snow in Maritime Antarctica. Antarct Sci 25:1–9. doi:10.1017/S0954102013000060

Marshall WA, Chalmers MO (1997) Airborne dispersal of Antarctic terrestrial algae and cyanobacteria. Ecography 20:585–594

Pomeroy JW, Brun E (2001) Physical Properties of Snow. In: Jones H, Pomeroy J, Walker D, Hoham R (eds) Snow Ecology: An Interdisciplinary Examination of Snow-Covered Ecosystems. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 45–118

Järvinen O, Leppäranta M (2013) Solar radiation transfer in the surface snow layer in Dronning Maud Land, Antarctica. Polar Sci 7:1–17

Brandt RE, Warren SG (1993) Solar-heating rates and temperature profiles in Antarctic snow and ice. J Glaciol 131(39):99–110

Wong CY, Chu WL, Marchant H, Phang SM (2007) Comparing the response of Antarctic, tropical and temperate microalgae to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) stress. J Appl Phycol 19:689–699. doi:10.1007/s10811-007-9214-3

Malanga G, Calmanovici G, Puntarulo S (1997) Oxidative damage to chloroplasts from Chlorella vulgaris exposed to ultraviolet-B radiation. Physiol Plantarum 101:455–462

Rautenberger R, Huovinen P, Gómez I (2015) Effects of increased seawater temperature on UV-tolerance of Antarctic marine macroalgae. Mar Biol 162:1087–1097

Clarke LJ, Robinson SA, Hua Q, Ayre DJ, Fink D (2012) Radiocarbon bomb spike reveals biological effects of Antarctic climate change. Glob Chang Biol 18:301–310

Vincent WF (2007) Cold Tolerance in Cyanobacteria and Life in the Cryo- sphere. In: Seckbach (Ed.), Algae and Cyanobacteria in Extreme Envi- ronments. Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 287e301.

Amoroso A, Domine F, Esposito G, Morin S, Savarino J, Nardino M, Montagnoli M, Bonneville JM, Clement JC, Ianniello A, Beine HJ (2010) Microorganisms in dry polar snow are involved in the exchanges of reactive nitrogen species with the atmosphere. Environ Sci Technol 44:714e719

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the PhD Grant DT_09-14 from Instituto Antártico Chileno (INACh) and Project ANILLO ART1101, from Conicyt. The logistic support provided by INACh and the collaboration of the staff of Base Julio Escudero Station are greatly acknowledged. This is contribution # 9 of the ANILLO ART1101 project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Framing hypotheses/experimental design: CR, NN, PH, IG. Laboratory or field work: CR, NN. Data analysis and interpretation: CR, NN, PH, IG. Manuscript preparation: CR, NN, PH, IG. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Rivas, C., Navarro, N., Huovinen, P. et al. Photosynthetic UV stress tolerance of the Antarctic snow alga Chlorella sp. modified by enhanced temperature?. Rev. Chil. de Hist. Nat. 89, 7 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40693-016-0050-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40693-016-0050-1