Abstract

Introduction

Commissioning, calibration, and quality control procedures for nuclear medicine imaging systems are typically performed using hollow containers filled with radionuclide solutions. This leads to multiple sources of uncertainty, many of which can be overcome by using traceable, sealed, long-lived surrogate sources containing a radionuclide of comparable energies and emission probabilities. This study presents the results of a quantitative SPECT/CT imaging comparison exercise performed within the MRTDosimetry consortium to assess the feasibility of using 133Ba as a surrogate for 131I imaging.

Materials and methods

Two sets of four traceable 133Ba sources were produced at two National Metrology Institutes and encapsulated in 3D-printed cylinders (volume range 1.68–107.4 mL). Corresponding hollow cylinders to be filled with liquid 131I and a mounting baseplate for repeatable positioning within a Jaszczak phantom were also produced. A quantitative SPECT/CT imaging comparison exercise was conducted between seven members of the consortium (eight SPECT/CT systems from two major vendors) based on a standardised protocol. Each site had to perform three measurements with the two sets of 133Ba sources and liquid 131I.

Results

As anticipated, the 131I pseudo-image calibration factors (cps/MBq) were higher than those for 133Ba for all reconstructions and systems. A site-specific cross-calibration reduced the performance differences between both radionuclides with respect to a cross-calibration based on the ratio of emission probabilities from a median of 12–1.5%. The site-specific cross-calibration method also showed agreement between 133Ba and 131I for all cylinder volumes, which highlights the potential use of 133Ba sources to calculate recovery coefficients for partial volume correction.

Conclusion

This comparison exercise demonstrated that traceable solid 133Ba sources can be used as surrogate for liquid 131I imaging. The use of solid surrogate sources could solve the radiation protection problem inherent in the preparation of phantoms with 131I liquid activity solutions as well as reduce the measurement uncertainties in the activity. This is particularly relevant for stability measurements, which have to be carried out at regular intervals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is a growing interest in the use of quantitative single-photon emission computed tomography and X-ray computed tomography (SPECT/CT) imaging, driven by a surge in theranostics and the need to optimise the absorbed doses delivered in molecular radiotherapy [1]. Absolute quantification in SPECT/CT imaging enables the direct evaluation of the activity concentration within a given volume of tissue, where the number of counts in each voxel is proportional to the activity. Although the individual steps for calibrating SPECT systems are well described [2], there are many sources of uncertainties associated with this process, including phantom preparation and radionuclide calibrator measurements, as well as those associated with reconstruction, image correction methods and post-processing of the images.

Radioiodine (131I) is still one of the most commonly used radionuclides in molecular radiotherapy, which is mainly used for the treatment of benign and malignant thyroid disorders [3]. Quantitative imaging for dosimetry of 131I-based radiopharmaceuticals with a marketing authorisation is applied in several clinical use cases. This comprises the treatment of benign thyroid diseases [4, 5], thyroid cancer [6, 7] with Na[131I]I or neuroendocrine tumours with [131I]mIBG. [8, 9].

133Ba has been previously proposed as a potential surrogate for the calibration of 131I imaging due to its longer half-life and similarity in the energy of its most abundant gamma-ray at 356 keV, as compared to 364 keV for 131I. Zimmerman et al. assessed activity quantification using planar, SPECT, and SPECT/CT imaging in an international multi-centre study using traceable 133Ba sources as a surrogate for 131I [10]. Based on data from the participants in nine countries, the authors concluded that solid surrogate sources could help in avoiding inherent problems with on-site activity measurements and phantom preparation in multi-centre studies. Moreover, large uncertainties for planar and SPECT imaging led to the conclusion that SPECT/CT was the preferred method. They also demonstrated the need for training and standardised acquisition and processing protocols to achieve accurate and reproducible activity quantification.

In the light of this knowledge, the EMPIR MRTDosimetry project, formed by a European collaboration between metrologists and nuclear medicine researchers, undertook the development and testing of traceable 133Ba sources that could replace liquid 131I for commissioning, calibration and quality control of quantitative SPECT/CT imaging. This publication presents the design and traceable production of two sets of 133Ba cylinders at two National Metrology Institutes, the standard operating procedure (SOP) for quantitative SPECT/CT imaging, and the results from a comparison exercise performed within seven members of the consortium with access to eight SPECT/CT systems. To improve reproducibility of future studies, the SOP as well as the source designs has been made available in an open data repository [11].

Methods

Participants and equipment

Seven members of the MRTDosimetry consortium participated in the comparison exercise (Azienda USL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust, Lund University, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Royal Surrey NHS Foundation Trust, “THEAGENIO” Anticancer Hospital, and University Hospital Würzburg). The participants were required to have access to a SPECT/CT system with high-energy collimators as well as methods for attenuation and scatter correction. In total, eight SPECT/CT imaging systems (5 × General Electric (GE) and 3 × Siemens) were included in the study. The individual setup details are given in Table 1, where four different combinations of reconstruction and correction methods were performed with system 2 (setups S2a-S2d). The description of the acquisition and reconstruction settings are provided in later sections.

Phantom design

SPECT/CT activity calibration factors are often determined in large-volume phantoms to reduce the influence of the partial volume effect. However, the production of such a large cylinder uniformly filled with a sufficiently high activity concentration of solidified 133Ba is challenging. Therefore, the comparison exercise was performed based on a set of four smaller cylinders of different sizes, similar to those proposed by Zimmerman et al. [10]. Although it was not the primary aim of this study, the resulting multi-centre dataset was used to provide a comparison of the relative impact of spatial resolution and partial volume effects between 131I and 133Ba within the cross-comparison.

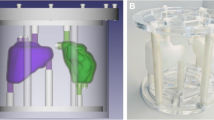

Computer-aided designs (CADs) for cylinders with four active volumes (Table 2) were produced (Fig. 1a). A wall thickness of 3 mm was used, with no difference in attenuation expected due to the nearly equivalent attenuation of water and resin in the expected energy range (0.078% difference in attenuation for 344 keV [15]). To enable an evaluation of the partial volume effect, different height diameter ratios at a constant height were used. Two versions of cylinder caps were designed, one for containing a resin mixed with 133Ba and one for injection of a solution with 131I. A thread was glued to the bottom of the cylinders to enable mounting the cylinders to a custom-made baseplate using double-threaded plastic rods. Cylinders and caps were produced using a stereolithography (SLA) 3D printing system (Formlabs Form 2) using the Formlabs Tough (v5) photopolymer resin formulation (density when cured = (1.15–1.20) g·cm−3), resulting in a durable and partially transparent model (a useful feature for judging the level when filling). Threads (M3) were added to the injection caps before being fixed into position using epoxy resin and tested to ensure the resulting models were watertight. The designs can be downloaded from the MRTDosimetry data repository [11].

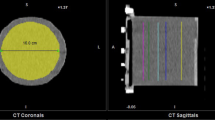

To optimise the placement of the sources in a standard Jaszczak phantom (cylinder with a fillable volume of 21.6 cm diameter and 18.6 cm height), the collimator-dependent spill-out of counts was estimated by the convolution of a Gaussian function with 20 mm full width at half maximum. This value was chosen to provide a representative worst-case scenario of the reconstructed spatial resolution for 131I based on previous experience with the calibration of SPECT/CT systems with radioiodine in a clinical setting, but was not specifically measured in this study. A laser-cut baseplate for attachment of the sources was produced according to this optimal positioning. For a SPECT/CT measurement, the baseplate and the support rods were mounted in the Jaszczak cylinder, four cylinders (either one of two sets of 133Ba solid sources or liquid 131I sources) were attached to the mounting baseplate, and the Jaszczak cylinder was filled with water.

Solid 133Ba source production

Two sets of 133Ba cylinders (four inserts each) were produced, one at the Laboratoire National Henri Becquerel (CEA) and one at the Czech Metrology Institute (CMI).

Commissariat à l'énergie atomique et aux énergies alternatives (CEA) sources

At CEA, a two-component epoxy resin (Stycast 1264, [16]) was spiked with 133Ba. The amine component was mixed with a limited amount of radioactive aqueous phase, and after mixing with the epoxy component for 30 min, the spiked resin was cured at room temperature (~ 48 h total solidification time). The resulting spiked resin has a density of (1.140 ± 0.011) g·cm−3 (k = 1). The uniformity of the 200 mL batch was assessed by measuring eighteen 2.5 mL subsamples by 4π gamma counting, aliquoted throughout the whole filling process of the four geometries. The dispersion was below 0.1%. The activity of the resin measured by gamma spectrometry for each geometry was in agreement with the spiking value derived from weighing. The relative combined standard uncertainty on the activity in each cylinder is 1.3%, which is below the 2.0% target limit. Following ISO 9978 standard, leakage and contamination tests were conducted: wipe test on the spiked resin, wipe test on the closed vessels, and an immersion test. For the wipe tests, the detection limit reached was below 1 Bq and no activity was detected. For the immersion test, a closed geometry filled with 1 MBq of 133Ba spiked resin was immersed in water at room temperature for up to 4 days. The water was measured by gamma spectrometry, and no activity was measured (detection limit of 0.21 Bq). Figure 1b shows the unfinished sources during production.

Czech metrology institute (CMI) sources

CMI developed a set of reference 133Ba sources with the radionuclide fixed in two-component silicone rubber Lukopren (Lučební závody Kolín, Czech Republic). Drops of 133Ba water solution were added into the liquid rubber and stirred well. Pouring the second component of the rubber resulted in solidification of the solution within a few tens of minutes, fixing the radionuclide in the matrix. Distribution of the radionuclide was uniform within ± 1% in the whole volume of the solidified source. As with the CEA sources, an immersion test according to ISO9978, in Sect. 5.1.4, was applied to measure the radioactivity leakage from the manufactured encapsulated sources. Results of measurement with liquid scintillation analyser Tri-Carb 2910TR (PerkinElmer, USA) were below the detection limit of 1 Bq for all four sources. The relative combined standard uncertainty of the activity of the manufactured sources reached 1.1% and consisted of the uncertainty of the silicone rubber density (1.0%), activity of 133Ba stock solution (0.4%), and weighting (0.06%).

Solid 133Ba phantom preparation

The two sets of sources were sequentially distributed to the participating centres during the comparison exercise. In addition, each participant received a mounting baseplate, support rods, a set of screws, and a set of empty 3D-printed cylinders to be filled with the 131I solution.

Liquid 131I phantom preparation

Two phantoms containing 131I were prepared at each site: a uniformly filled Jaszczak cylindrical phantom to assess the setup-specific image calibration factor (ICF) and a phantom containing the set of four 3D-printed fillable cylinders to assess the partial volume effect.

The 131I activity for the ICF assessment with the Jaszczak phantom was measured in the local radionuclide calibrator before and after injection into the phantom using a traceable 131I calibration factor (dial setting specific to the radionuclide, measurement container, measurement geometry inside the calibrator, and filling level). To ensure a uniform activity distribution of the volatile 131I in the phantom, a carrier solution of sodium hydroxide (0.1 mol dm−3) with inactive iodine (10 μg g−1) was used. The activities of the ICF measurement at the time of SPECT scanning had a median value of 39.9 MBq (range 34.2–86.9 MBq).

For the four fillable cylinders, a stock solution was prepared at each site by weighing a container before and after adding 160 mL of sodium hydroxide (0.1 mol dm−3) with inactive iodine (10 μg g−1) as carrier solution as well as ~ 30 MBq of liquid 131I (from traceable activity measurement as described for the ICF measurement). The activity concentration was calculated as the ratio of dispensed activity to volume. The cylinders were filled by weighing each empty cylinder separately, injecting the stock solution, and re-weighing the filled cylinder. The activity inside each cylinder was then calculated as the product of activity concentration and active volume. The total 131I activity concentrations at the time of SPECT scanning had a median of 0.18 MBq·mL−1 (range 0.16–0.21 MBq mL−1) corresponding to total activities of 0.30, 1.2, 4.9, and 19 MBq in the cylinders with 7.5 (C1), 15 (C2), 30 (C3), and 60 (C4) mm diameter, respectively. As with the 133Ba cylinders, the 131I cylinders were attached to the mounting baseplate with the rods, and the phantom was filled with water.

Data acquisition and reconstruction

The measurements included the ICF determination with the Jaszczak phantom and separate measurements of the three sets of four small cylinders (CEA 133Ba, CMI 133Ba, and liquid 131I) mounted in the water filled Jaszczak phantom. All measurements within the scope of the exercise were performed according to a dedicated SOP, containing information on the required equipment, instructions on energy peak alignment (mandatory), uniformity quality control (optional), phantom filling and positioning, SPECT/CT acquisition parameters, reconstruction and correction methods, delineation of volumes of interest (VOI), and file transfer.

SPECT/CT imaging of the phantoms was performed according to the acquisition parameters given in Table 3. The acquisitions were performed with the phantom (placed with the largest cylinder phantom insert closest to the patient bed) oriented axially using a high-energy collimator and with a standard low-dose CT protocol for attenuation correction. An example of the fully assembled phantom and its positioning on a SPECT/CT system can be seen in Fig. 1c. For 133Ba acquisitions, an energy peak alignment was performed using the smallest 133Ba source. A 60-min acquisition was performed for the 131I ICF measurement, while 30-min acquisitions were performed for all cylinder measurements (CEA and CMI 133Ba, and 131I). The images were reconstructed using an ordered subset expectation maximisation (OSEM) iterative reconstruction with 30 iterations and 2 subsets without post-filtering [17]. Convergence had previously been verified at a representative site. The use of triple energy window (TEW) scatter correction and resolution recovery methods was recommended. However, the comparison exercise also included participants with small differences in the reconstruction software and corrections applied, as in the case of participant 3, which used in-house reconstruction software and the ESSE scatter correction. Details on the reconstruction software and scatter correction method used by each participant are shown in Table 1. Examples of SPECT/CT reconstructions of solid CEA 133Ba sources and 131I-filled cylinders are given in Figs. 1d and e, respectively.

Data analysis

Analysis of the solid 133Ba and the liquid 131I measurements

First, the ICF for 131I was calculated based on the SPECT images of the Jaszczak cylinder as:

Here, \({C}_{Jasz}\) is the number of counts in an enlarged CT-based VOI placed around the uniformly filled Jaszczak cylindrical phantom to account for partial volume effect, \({T}_{Jasz}\) is the acquisition time duration, and \({A}_{Jasz}\) is the activity in the phantom as measured in the radionuclide calibrator and decay corrected to the time of acquisition.

For each of the cylinder inserts (131I and 133Ba), a pseudo-ICF value, by which ICF values that are influenced by partial volume effects (reduced ICF due to spill-out) will be described hereafter, was calculated as:

Here, \({C}_{cyl}\) is the number of counts in the cylinder VOI, \({T}_{cyl}\) is the acquisition time duration, and \({A}_{cyl}\) is the activity in the phantom decay corrected to the time of acquisition. The choice of VOI drawing technique was left to the participating sites to reflect the heterogeneity in clinical workflows. However, care was taken in the evaluation to only compare VOIs whose volumes matched the cylinder volumes. While one site chose to draw the VOIs based on the nominal cylinder dimensions (S1), all other sites used a thresholding method to match the physical active volume of the given cylinder (S2-S8).

The combined standard uncertainty in the ICF and pseudo-ICF values was calculated as the square root of the sum of the squared standard uncertainty components, including counts, time, and activity. As the study design required on-site reconstruction, projection data were not available, and therefore, the uncertainty in the counts within the considered volume was assumed to follow Poisson statistics and calculated as the square root of the number of counts [18]. A one-second uncertainty in scan duration was assumed for all the scans acquired. The uncertainty on the radionuclide calibrator measurements included the uncertainty on the calibration setting, reproducibility, linearity, uncertainty due to background correction, uncertainty associated with decay correction, and statistical uncertainty. The sources of uncertainty related to the measurement on the radionuclide calibrators were considered to follow a normal distribution. The weighing uncertainty was also considered for each cylinder, and a rectangular distribution was assumed. The contribution to the standard uncertainties was combined in quadrature to estimate the combined standard uncertainty of the activity dispensed to the cylinders.

The differences between the pseudo-ICFs obtained with the CEA and CMI 133Ba sources were assessed for statistical significance using a nonparametric two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test under the null hypothesis of zero median for the differences between the paired CEA and CMI pseudo-ICF values.

Cross-calibration between 133Ba and 131I

The relationship between the pseudo-ICFs for liquid 131I and solid 133Ba was studied based on a setup-specific cross-calibration line, which relates the 131I-based counts measured on a specific system for the cylinder geometry of different sizes to the 133Ba-based counterparts. Due to setup- as well as radionuclide-specific differences, the linear relationship differs from a cross-calibration based on only the ratio of 133Ba and 131I emission intensities. To test the performance of an experimental site-specific cross-calibration, the correlation between 133Ba and 131I pseudo-ICFs for each setup was determined by fitting a non-weighted linear model. The relative percentage change between 131I and 133Ba, corrected with both setup-specific and emission probability-based cross-calibrations, were calculated to assess the performance of both cross-calibration methods. In addition, to assess the potential use of 133Ba sources to calculate a volume-dependent partial volume correction, pseudo-recovery curves (pseudo-ICF against volume) were determined for 131I, uncorrected 133Ba, and 133Ba corrected with both cross-calibration methods by fitting a non-weighted non-linear model.

Results

A representative example of the design and fabrication of the cylindrical sources as well as SPECT/CT measurements and reconstructions of the physical phantom with the cylindrical sources are shown in Fig. 1.

a CAD models of the solid and fillable cylinders including cap, b production of the solid sources at CEA, (c) SPECT/CT measurement of the four cylinders mounted in a Jaszczak cylindrical phantom, (d) SPECT/CT fusion of the CEA 133Ba sources measured with setup S7, (e) SPECT/CT fusion of the liquid 131I sources measured with setup S7

Solid 133Ba measurements

The Wilcoxon test for the two 133Ba sets of sources showed no evidence to reject the null hypothesis of zero median difference between the CMI and CEA sources at a 5% confidence level (P = 0.32). Therefore, for the rest of the analysis, the two 133Ba measurements were combined using the average value. For completeness, a plot of the individual 133Ba cylinder pseudo-ICFs for the CEA and CMI sources as well as a table with the numerical values can be found in Additional file 1. The uncertainty in the averaged pseudo-ICF (\(\overline{Pseudo{\text{-}}ICF}\)) includes two components combined in quadrature: the uncertainty of the average calculated from the propagation of uncertainties of the two uncorrelated measurements and an additional uncertainty to account for the deviation between the two measurements assuming a uniform distribution [19]:

The individual CEA and CMI pseudo-ICFs as well as their combined average are provided as supplementary material. The averaged pseudo-ICFs for the 133Ba cylinders are shown in Fig. 2a. All Siemens systems (S1, S7, and S8) show similar pseudo-ICFs, with a slight increase for S8, which has a thicker crystal and therefore a higher sensitivity. GE systems using the vendor reconstruction software (S2a, S4, and S5) also have comparable ICFs and have the highest pseudo-ICFs of all setups. GE acquisitions reconstructed using the vendor neutral Hermes (Hermes Medical Solutions, Stockholm, Sweden) (S2a-d and S6) and in-house software (S3) show lower ICFs than the GE reconstruction. Of these, S2b, which uses Hermes Monte Carlo-based scatter and resolution recovery methods, shows an increase in ICF as compared to the other Hermes-based reconstructions. The larger uncertainties observed in some of the cylinders, e.g. C2-C4 for S4, are due to a larger deviation between the two measurements. As expected, a reduction in pseudo-ICF values with decreasing volumes was observed for all setups due to an increase in partial volume-related spill-out of counts.

a 133Ba-cylinder combined average pseudo-ICFs, b 131I cylinder pseudo-ICFs and ICF from the uniformly filled Jaszczak phantom measurement. Note that both data sets are shown in the same y-axis scale. A plot of the individual 133Ba cylinder pseudo-ICFs for the CEA and CMI sources and a table with the numerical values can be found in Additional file 1

Liquid 131I measurements

The pseudo-ICF values based on the small cylinders and the ICF values based on the large-volume Jaszczak phantom for 131I are shown in Fig. 2b. During the data analysis, an inconsistency was observed in the 131I data reported by S6; therefore, the data of this site have not been used in the rest of the comparison between 133Ba and 131I.

As with the 133Ba measurements, the ICF and pseudo-ICF values vary depending on the system vendor and setup, showing similar variations as 133Ba for the different reconstruction and correction methods. Again, a partial volume-related reduction in pseudo-ICF values with decreasing volumes was observed.

Comparison between 133Ba and 131I

The setup-specific cross-calibration lines (i.e. the relationship between the pseudo-ICF values of 131I and 133Ba) are shown in Fig. 3. In addition, the ratio between the gamma-ray emission probabilities (0.764 ± 0.005) of the 356 keV 133Ba energy peak (62.05 ± 0.19) % and the 364 keV 131I energy peak (81.2 ± 0.5) % is displayed for reference [20, 21]. The corresponding fit parameters are given in Table 4.

Setup-specific cross-calibration between 133Ba and 131I. The solid line represents the setup-specific cross-calibration line (linear model fit, see Table 4), and the dashed line represents the ratio of the emission probabilities between 133Ba and 131I. Note that the 133Ba pseudo-ICF values represent the combined average between both sources

As has been pointed out in 2000 by Dewaraja et al. [22], septal penetration by high-energy photons of 131I (723 keV, 637 keV) contributes substantially to the background. The conventional TEW technique for background correction might thus lead to a difference between true scatter and the TEW estimate in the order of 10–20%. As a consequence, this effect would slightly lower the value of the correction factor, which explains the mainly lower slope of the correction line compared to the theoretical slope.

The relative differences between the 131I and 133Ba pseudo-ICFs cross-calibrated with the setup-specific cross-calibration line and emission probability-based ratio are shown in Fig. 4. The median [range] absolute relative difference across setups is reduced from 12 [0.065–67] % to 1.5 [0.25–4.5] % when the site-specific cross-calibration method is used, with the largest improvements observed in the smallest cylinders.

The pseudo-recovery curves for 131I, 133Ba, 133Ba cross-calibrated using the theoretical ratio of emission probabilities, and 133Ba cross-calibrated using the setup-specific cross-calibration line from Table 4 are shown in Fig. 5. A good agreement between the 131I and 133Ba curves is shown for all sites when using the setup-specific cross-calibration line, highlighting the potential use of 133Ba sources to determine recovery coefficients to correct for partial volume effects.

Pseudo-recovery curves (ICF values in cps/MBq as a function of cylinder volumes) for: 131I (red circle), 133Ba (purple star), 133Ba cross-calibrated (cc) using the theoretical emission probabilities ratio (green square), and 133Ba cross-calibrated using the experimentally measured setup-specific factors from Table 4 (blue cross). Note that each pair of subplots in a row has different scales in the y-axes

Discussion

In this study, the experimental setup-specific cross-calibration between 131I and 133Ba deviated significantly from the ratio 0.764 ± 0.005 of gamma-ray emission probabilities of 133Ba (62.05 ± 0.19) % and 131I (81.2 ± 0.5) % [20, 21] and was observed to be highly dependent on the setup used. Although the deviation was smaller for setups including a Monte Carlo-based scatter correction, a site-specific cross-calibration procedure is recommended. Once a setup-specific cross-calibration line is in place, however, quality control measurements such as stability measurements can be performed based on solid 133Ba sources only. This solves the radiation protection problem inherent in the preparation of phantoms with liquid activity solutions and reduces the measurement uncertainties in the activity.

One thing that should be noted is that the uncertainty calculation for the pseudo-ICF values includes the counts inside the cylinders taken from the reconstructed attenuation-corrected images. Given the small number of total counts in the smallest cylinder, this might lead to a considerable overestimation of the counts and, as a result, to an underestimation of the uncertainties especially for the small cylinders. Similarly, the assumption that the counts within the considered volumes can be approximated by Poisson statistics might lead to an underestimation of the uncertainty in the number of counts, in particular for the smaller cylinder inserts. However, our study design required on-site reconstruction (including attenuation correction) and analysis by each participating site before results were collected for evaluation, which eliminated the possibility of a projection-based calculation of the uncertainty. While not investigated in this work, a more detailed analysis of the resulting attenuation-dependent underestimation of the uncertainty could become part of a follow-up study.

Although a more detailed analysis of a potential partial volume correction would have been interesting, it was not possible on the basis of the available data. For example, the enlarged VOIs (i.e. including counts lost due to spill-out) proposed in the SOP for that very purpose were not available for all sites. The available VOIs had the same (nominal cylinder) volume, but had been drawn using different VOI drawing methods, the choice of which (exact vs. threshold-based) can lead to additional non-negligible differences in pseudo-ICF, and prevented a systematic analysis of partial volume errors. This shortcoming is inherent in the study design and needs to be improved in future studies.

Other radionuclides with similar main energies could potentially be better suited as an analogue for 131I for imaging than 133Ba. As an example, 113Sn has only one major gamma emission line at (391.698 ± 0.007) keV (emission probability: (64.97 ± 0.17) %). However, due to the shorter half-life of 115.1 days, this radionuclide is useful for system calibration, but limited as a source for system stability assessments and long-term quality control compared to a long-lived source such as 133Ba with a half-life of 10.5 years. A potential solution could be to calibrate a system with a traceable 113Sn source and use a cross-calibrated 133Ba source for system stability assessments. Although 133Ba has been shown not to be a good substitute for 131I in radionuclide calibrator measurements, this knowledge is of minor importance in the cross-calibration of SPECT/CT systems, since solid sources are typically produced or supplied with traceable activities and consequently do not need to be measured in the radionuclide calibrator.

Although this exercise was affected by challenges associated with the logistics of the source transportation, the long half-life of 133Ba mitigated any issues arising from this. While the inland transport between the UK sites was rather straightforward, transportation between different countries as UN2910 radioactive material excepted package turned out to be difficult due to differences in the regulations of participating countries. In addition, source transport via air proved to be not firmly plannable as the decision whether to carry the sources is the sole responsibility of the respective aircraft pilot. Consequently, in some instances, the sources had to be spontaneously transported by road between participating countries such as from Germany to the UK or, even more costly, from Sweden to Italy. Therefore, the logistics and potentially high transportation costs must be taken into full consideration when planning an international multi-centre study to avoid any major delays.

This study demonstrated that 133Ba can be used as a surrogate for liquid 131I for quality control and quantitative SPECT/CT. The use of 133Ba greatly reduces the time needed for preparation of quality control measurements (no preparation of stock solution or phantom filling) and can mitigate potential errors in the source preparation. The use of solid 133Ba sources also provides benefits in reduced radiation exposure and volatility.

Conclusion

This study presented the results of an international comparison exercise on the feasibility of a reliable calibration of SPECT/CT systems for quantitative 131I imaging based on a set of 133Ba surrogate sources following a harmonised protocol. Based on the results obtained from eight imaging centres, a site-specific cross-calibration is recommended to minimise the differences between 131I and 133Ba. In multi-centre setups, care should be taken that different sites follow the same VOI drawing technique, as this had a major impact on the cross-calibration especially for the smaller sources. In summary, the use of traceable 133Ba sources has the potential to reduce the inherent problems with on-site activity measurement and phantom preparation with 131I.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Flux G, Bardies M, Monsieurs M, Savolainen S, Strands SE, Lassmann M, et al. The impact of PET and SPECT on dosimetry for targeted radionuclide therapy. Z Med Phys. 2006;16(1):47–59.

Tran-Gia J, Denis-Bacelar AM, Ferreira KM, Robinson AP, Calvert N, Fenwick AJ, et al. A multicentre and multi-national evaluation of the accuracy of quantitative Lu-177 SPECT/CT imaging performed within the MRTDosimetry project. EJNMMI Phys. 2021;8(1):55.

McCready VR. Radioiodine - the success story of Nuclear Medicine : 75th Anniversary of the first use of Iodine-131 in humans. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;44(2):179–82.

Stokkel MP, HandkiewiczJunak D, Lassmann M, Dietlein M, Luster M. EANM procedure guidelines for therapy of benign thyroid disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37(11):2218–28.

Hänscheid H, Canzi C, Eschner W, Flux G, Luster M, Strigari L, et al. EANM Dosimetry Committee series on standard operational procedures for pre-therapeutic dosimetry II Dosimetry prior to radioiodine therapy of benign thyroid diseases. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40(7):1126–34.

Luster M, Clarke SE, Dietlein M, Lassmann M, Lind P, Oyen WJ, et al. Guidelines for radioiodine therapy of differentiated thyroid cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35(10):1941–59.

Taprogge J, Vergara-Gil A, Leek F, Abreu C, Vavrova L, Carnegie-Peake L, et al. Normal organ dosimetry for thyroid cancer patients treated with radioiodine as part of the multi-centre multi-national Horizon 2020 MEDIRAD project. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2023;50(11):3225–34.

Giammarile F, Chiti A, Lassmann M, Brans B, Flux G. EANM procedure guidelines for 131I-meta-iodobenzylguanidine (131I-mIBG) therapy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35(5):1039–47.

Gear J, Chiesa C, Lassmann M, Gabina PM, Tran-Gia J, Stokke C, et al. EANM Dosimetry Committee series on standard operational procedures for internal dosimetry for 131I mIBG treatment of neuroendocrine tumours. EJNMMI Phys. 2020;7(1):15.

Zimmerman BE, Grosev D, Buvat I, Coca Perez MA, Frey EC, Green A, et al. Multi-centre evaluation of accuracy and reproducibility of planar and SPECT image quantification: an IAEA phantom study. Z Med Phys. 2017;27(2):98–112.

Robinson A. MRTDosimetry Data Repository 2021. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/69NGE.

Ogawa K, Harata Y, Ichihara T, Kubo A, Hashimoto S. A practical method for position-dependent Compton-scatter correction in single photon emission CT. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1991;10(3):408–12.

Sohlberg AO, Kajaste MT. Fast Monte Carlo-simulator with full collimator and detector response modelling for SPECT. Ann Nucl Med. 2012;26(1):92–8.

Frey EC, Tsui B (eds) A new method for modeling the spatially-variant, object-dependent scatter response function in SPECT. In: 1996 IEEE nuclear science symposium conference record; 1996: IEEE.

Solc J, Vrba T, Burianova L. Tissue-equivalence of 3D-printed plastics for medical phantoms in radiology. J Instrum. 2018;13(09):P09018.

Zimmerman BE, Cessna JT. Development of a traceable calibration methodology for solid 68Ge/68Ga sources used as a calibration surrogate for (18)F in radionuclide activity calibrators. J Nucl Med. 2010;51(3):448–53.

Hudson HM, Larkin RS. Accelerated image reconstruction using ordered subsets of projection data. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1994;13(4):601–9.

Mou T, Huang J, O’Sullivan F. The gamma characteristic of reconstructed PET images: implications for ROI analysis. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2018;37(5):1092–102.

Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology. JCM 100—Evaluation of measurement data—Guide to the expression of uncertainty in measurement. BIPM. 2008.

Bé M-M, Chisté V, Dulieu C, Browne E, Chechev V, Kuzmenko N, et al. Table of Radionuclides. Pavillon de Breteuil, Sévres: Bureau International des Poids et Mesures; 2004.

Bé M-M, Chisté V, Dulieu C, Kellett MA, Mougeot X, Arinc A, et al. Table of Radionuclides. Pavillon de Breteuil, Sévres: Bureau International des Poids et Mesures; 2016.

Dewaraja YK, Ljungberg M, Koral KF. Characterization of scatter and penetration using Monte Carlo simulation in 131I imaging. J Nucl Med. 2000;41(1):123–30.

Acknowledgements

We also thank the entire MRTDosimetry collaboration: Manuel Bardiès, Salvatore Berenato, Ilias Bilas, Marco Capogni, Maxime Chauvin, Maurice Cox, Jérémie Dabin, Marco D’Arienzo, Aida Hallam, Gunjan Kayal, Giuseppe Lorusso, Michael Ljungberg, Franz-Josef Maringer, Jamie Mewburn-Crook, Vere Smyth, Ludmila Štemberková, Lara Struelens, Alex Vergara-Gil, Hannah Wiedner.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The projects 15HLT06 MRTDosimetry and 19SIP01 PINICAL-MRT have received funding from the EMPIR programme co-financed by the Participating States and from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme. This work was also supported by the National Measurement System of the UK’s Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

JT-G, AMDB, KMF, APR, and MLa contributed to the design of the comparison exercise, global data analysis, and manuscript preparation. JT-G, KMF, APR, CB, SMC, AJF, VL, BS, JM-C, JSo, CT, and MLa contributed to the design and production of the solid sources and phantoms. JT-G, AMDB, KMF, APR, NC, LMB, AJF, DF, FF, KG, EG, WH, SJJ, MK, MLj, DRM, JM-C, JSc, KSG, JT, JW, and MLa contributed to local data collection and analysis for the comparison exercise. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Michael Lassmann has received institutional grants by IPSEN Pharma, Nordic Nanovector, and Novartis. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article exist.

Additional information

Maria Kotzasarlidou passed away in December 2020 after participating in the experimental part of this project.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

133Ba-cylinder pseudo-ICFs for the individual CEA and CMI sources and the combined average, with the corresponding uncertainties.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tran-Gia, J., Denis-Bacelar, A.M., Ferreira, K.M. et al. On the use of solid 133Ba sources as surrogate for liquid 131I in SPECT/CT calibration: a European multi-centre evaluation. EJNMMI Phys 10, 73 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40658-023-00582-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40658-023-00582-3