Abstract

Enzymatic degradation of synthetic dyes holds an immense promise for addressing the environmental concerns associated with the textile and dye industries. This study aimed to isolate bacteria capable of producing laccase enzymes from an anthropogenic environment. Subsequently, viability of utilizing cost-effective agricultural residues as substrates for laccase production was assessed. Response Surface Methodology (RSM) and the One Variable at a Time (OVAT) approach was pursued for the optimization of laccase production, followed by pH and temperature stability, dye degradation and decolorization experiments, toxicological studies on the degraded dye metabolites. In results, laccase-producing bacterial strain was identified as Stenotrophomonas maltophilia strain E1 (S. maltophilia). Among variety of substrates, coconut husk exhibited optimal efficacy. In a statistical optimization study, it was found that S. maltophilia was capable of producing laccase 51.38 IU/mL, i.e., three times higher than the amount of laccase produced by unoptimized medium (16.7 IU/mL), and the enzyme activity was found to be steady at an acidic pH, and a mesophilic temperature range. The laccase obtained from S. maltophilia E1 demonstrated proficient dye decolorization capabilities, achieving a notable 92.1% reduction in Malachite green dye coloration at a concentration of 500 ppm. Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) analysis of the decolorized derivatives of Malachite green revealed a conversion into a distinct compounds. Moreover, after undergoing laccase treatment, Malachite green exhibited decreased phytotoxic effects on Oryza sativa, pointing to enzymatic detoxification. Collectively, insights gained from the present study will contribute to the development of efficient enzymatic approaches for addressing the environmental pollution caused by synthetic dyes.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Laccase (EC 1.10.3.2) is a copper rich polyphenol oxidase that catalyzed the oxidation of a wide variety of substrates, which includes several types of phenolic and nonphenolic hazardous compounds (Agrawal et al. 2018; Jawale et al. 2021). A major reason for the interest in laccase is its broad range of substrate oxidation activity, the absence of cofactors, and the availability of oxygen as an electron acceptor, which makes them a potentially useful and versatile enzyme with number of biotechnological applications. Therefore, laccases are applied in several industrial processes including, pulp and paper (Aracri et al. 2009), textile (Mandic et al. 2019), cosmetics (Shin et al. 2019), pharmaceutical (Yang et al. 2017), food (Singh and Gupta 2020) and in numerous bioremediation processes (Nguyen et al. 2020; Patel and Patel 2020; Souza Vandenberghe et al. 2022).

The multi-copper laccase is broadly occurring in nature, found in bacteria, fungi, plants, archaea, as well as in insects (Uthandi et al. 2010). Among these microbial sources, there is a great deal of research being conducted to find novel microbial species exhibiting unique features to use them for laccase production (Jawale et al. 2021). Moreover, features like small generation time, high proliferation rate, easy to handle and the ability to produce large amount of products using cheap and natural raw materials make them more efficient (Thapa et al. 2020). The bacterial laccase is relatively extremely active and is significantly more stable under high temperatures, high pH conditions, as well as under high chloride concentrations in compare to fungal laccase (Margot et al. 2013). In recent years, significant progress has been made in the screening of bacteria for their laccase production (Akram et al. 2022; Mate and Alcalde 2015). Several studies have highlighted the diversity of bacteria capable of producing laccases. Recent research has expanded our knowledge about laccase-producing bacteria beyond traditional sources. For instance, extremophiles from extreme environments such as hot springs and deep-sea sediments have been identified as potential laccase producers, indicating the broad range of ecological niches for this enzyme (Chandra et al. 2017; Pham et al. 2023; Zhu et al. 2022). By analyzing the genetic material present in environmental samples via metagenomics, researchers have identified previously unknown laccase producers, unlocking new possibilities for industrial applications (Ausec et al. 2011; Dai et al. 2021; Ferrer et al. 2010). Furthermore, recent research efforts have resulted in the discovery of novel laccase variants with unique properties. These enzymes exhibit increased stability, substrate specificity and tolerance to harsh conditions, making them promising candidates for various biotechnological applications (Bisaccia et al. 2023; Chauhan et al. 2017). Automation and high-throughput screening techniques have accelerated the process of identifying laccase-producing bacteria. These methods allow researchers to quickly assess the enzymatic capabilities of a large number of bacterial strains, facilitating the discovery of promising candidates (Rodríguez-Escribano et al. 2017; Sarnaik et al. 2020). Furthermore, several studies reported the production of laccase by bacteria using low-cost agricultural wastes such as sawdust, corn, apple pomace, canola roots, sugarcane bagasse, cotton stalks and wheat bran (Kumar et al. 2022). These agriculture residues pose a serious threat to the environment if not managed properly. Therefore, using these wastes for the degradation and recycling of pollutants has become an important strategy to reduce the disposal problems (Chen et al. 2021).

In the textile and paper industries, thousands of different dyes are produced, released each year, and remain stable under environmental conditions that include chemicals, light exposure, and microbial degradation. In today’s world, over 10,000 synthetic dyes are used (Blánquez et al. 2019). Because of inherent recalcitrance nature of dye, it poses serious health issues. During dye degradation, dye molecules are decolorized and/or detoxified in contaminated environments by polluted effluents. In the past, several physico-chemical technologies have been studied for dye degradation in wastewater, including filtration, adsorption, photodegradation, and irradiation (Parshetti et al. 2006). Conventional physico-chemical treatments are effective, but ineffective when the dye is present in low concentrations, whereas sometimes it also generates toxic compounds (organochlorides and aromatic amines) that could be more toxic than the dye prior to pretreatment (Rueda-Villabona et al. 2021). Pretreatment using bacteria or enzymes has the advantage of total dye decolorization and breakdown of its intermediates as well as decreasing negative environmental effects (Patel and Patel 2020).

Biodegradation of dye is performed enzymatically through reduction, oxidation, hydroxylation and methylation reaction of dye’s structures (Rueda-Villabona et al. 2021). Laccase from bacteria and fungi are reported for their dye’s bioremediation potential. Till date, many dyes like Malachite green, Bromophenol blue, Remazol bright blue R, Methyl orange, Congo red, Coomassie G-250, Crystal violet, Alizarin red, Indigo blue etc., are reported to degrade by microbial laccase (Ardila-Leal et al. 2021). Apart from fungi, bacteria are emerging as a novel source to synthesize laccase with similar potential of fungal enzymes. Because of their various industrial application cost-effective usage, short time enzyme production, broad substrate specificity, bacterial laccase are the potential tools with many advantages (Ben Younes et al. 2021).

Aiming to promote industrial laccase use by isolating efficient laccase producers, we isolated S. maltophilia E1 that produces high laccase levels and decolorizes structurally different dyes efficiently. In the present study, isolated S. maltophilia E1 produce laccase in the presence of coconut husk as a substrate and decolorized dyes in the absence of a mediator. To optimize laccase production, a response surface methodology (RSM) was used. The decolorized and degraded malachite green was analyzed by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) analysis. Moreover, the degraded metabolites were further assessed by phytotoxicity test.

Materials and methods

Isolation and screening of laccase producing bacteria

The soil sample was collected in sterile tubes from the Amlakhadi located near Ankleshwer, Gujarat Industrial Development Corporation (GIDC) (21°36′55°N, 72°59′52°E), Gujarat, India. The sample was transported immediately to the lab in an icebox for further use. Soil sediment sample was sequentially diluted up to 10–8 and then 0.1 mL sample was spread on M162 agar medium supplemented with 2 g/L yeast extract, 2 g/L tryptone, 100 µM CuSO4, and 2 mM Guaiacol (Sondhi and Saini 2019). The plates were incubated at 37 ℃ for 48–72 h. The production of laccase was indicated by reddish brown color on the agar plate. Isolates were further screened for their laccase activity, which was carried out by embedding 2,2’azino-bis [3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulphonic acid] (ABTS) and syringaldazine in agar medium separately. Appearances of green color represent the true laccase producer.

Identification of laccase producing bacterial strain

Identification of potent laccase producing bacterial strains was conducted with the help of 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis. The genomic DNA was isolated through NaCl-cTAB method described by Wilson (2001). The conserved nucleic acid sequences of strains were multiplied by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) utilizing universal primers (reverse-1492r and forward-27f). The amplification system and required conditions were based on those given by Desai and Patel (2019). After sequencing, BLAST-analysis was conducted on the nucleotide sequences obtained using the reference sequences available at NCBI, GenBank.

Evaluation of laccase production by agro-residues waste

The laccase production study by means of submerge fermentation using commonly available agricultural waste residues i.e., sawdust, coconut husk, rice, wheat, and barley bran as substrate was carried out. The pretreatment for sawdust and coconut husk including, washing with distilled water, 15 min boiling to remove dust particles, and then drying at 60 ℃ in oven. After complete drying, obtained residues were milled through grinder, and passed through a 0.5 mm size sieve for uniform particle size (Prajapati et al. 2021). The laccase production via submerge fermentation was carried by incorporating 1% of each waste residues into 100 mL of M162 broth containing 2 g/L tryptone, 2 g/L yeast extract, and 100 µM CuSO4. Precisely, 1% (v/v) active culture (absorbance, A600nm: 0.8) was inoculated in the flask, followed by incubation at 37 ℃ for 48 h. After incubation, flask material was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min, and the supernatant was used to measure laccase activity using Guaiacol as a substrate.

Laccase assay

The enzyme activity was determined through monitoring the oxidation of 1 mL of 10 mM Guaiacol buffer using 3 mL (100 mM) sodium acetate buffer at 470 nm (Margot et al. 2013). Enzyme activity was expressed in International Units (IU), where 1 IU is described as the amount of enzyme essential to oxidize 1 µmol of Guaiacol per min under assay conditions. To calculate laccase activity, the following formula was used (Patel et al. 2009):

where, A = Absorbance at 470, V = total volume (mL), t = incubation time (min), e = coefficient of Guaiacol (26.6 m−1 M−1) at 470 nm, v = enzyme volume (mL).

Optimization of laccase production: conventional and statistical approach

The optimization of laccase production was initially conducted by conventional one variable at a time (OVAT) method. Parameters including incubation time (0–60 h), initial pH (3.0–9.0), temperature (25–50 ℃), and agitation speed (50–200 rpm) were selected for this study. Under this approach, at a given time, one variable was changed while the rest were kept unchanged. The BBD of the RSM was used for statistical optimization of process parameters. To optimize laccase productions, four functional variables were considered, including (A) coconut husk (g/L), (B) CuSO4 (µM), (C) yeast extract (g/L), and (D) pH. The laccase production was taken as dependent response variable (IU/mL). Table 1 shows the upper and lower limits for each variable. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used as the statistical method to determine the significance and adequacy of the model. Three-dimensional (3D) graphs, counter plots, and all statistical analyses were performed using Design Expert version 12 (Stat-Ease).

Influence of pH and temperature change on laccase activity and stability

The effect of pH variation was examined within the range of 2–10, using glycine–HCl, sodium citrate, carbonate-bicarbonate and potassium phosphate (50 mM) buffer. Temperature effects were examined in the context of 25–60 °C. The investigation revealed that one parameter was different, whereas the other remained constant, and vice-versa. An investigation of the product's stability under pH variations was conducted at 35 °C and pH values between 2 and 10. Using standard assay conditions, residual activity was determined after 6 h. As for thermal stability, the enzyme was incubated at 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 55 and 60 °C for up to 6 h. Aliquots were collected at regular time interval for testing enzyme activity under standard assay conditions. The Guaiacol was used as a substrate for both experiment, and activity was measured in the form of relative activity (%).

Dye decolorization and UV- Vis analysis

The optimized crude laccase (culture filtrate) of isolate E1 was further evaluated for its ability to decolorize dyes, such as Acid orange, Acid red 18, Congo red, Crystal violet, Malachite green, Orange B methyl orange, Methyl red, and Methylene blue. For the decolorization experiment, 100–500 ppm concentration dyes were dissolved separately in distilled water and then passed through Whatman No. 1 filter paper. Then, the action of decolorization was commenced by mixing 100 mL of each dye concentration and 10 mL of crude enzyme (51.38 ± 1.11 IU/mL) solution in 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer (pH—4.0) and allowing to stand at 35 ℃ for 24 h. The samples were withdrawn after incubation and the decolorization of dyes using a spectrophotometer at the maximum wavelength of each dye was measured. Controls containing dyes without the enzyme were used as negative controls. Decolorization experiments were conducted in triplicate in all cases. The following formula was used to calculate decolorization:

A spectrophotometric analysis of laccase-treated and untreated dye samples was conducted between the wavelengths 300 and 800 nm using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, India). For that, dye samples were initially centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 30 min and then supernatant was extracted with ethyl acetate at an equal volume.

Extraction of decolorized product of the dyes

Dye degradation assays were used to identify intermediate compounds resulting from dye decolorization. After collecting the decolorized solution, it was mixed thoroughly with an equal volume of ethyl acetate, and the two phases were vortexed. A rotary evaporator was used to collect and dry the separated organic layer (Ghobadi Nejad et al. 2019). The dried residues of test and control sample were further suspended in 3 mL of HPLC-grade methanol, mixed thoroughly, filtered by 0.45 µm filter and prepared for chromatographic analysis.

Gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC–MS) was used to characterize and identify the degraded products, whereas the untreated (control) solution was used as a reference. The filtered sample was applied for GC–MS with a DB-5 MS column (30 cm × 0.25 mm id., 0.25 mm film thickness) and helium as the carrier gas at a 1 mL/min flow rate. The instrument that was employed for GC–MS analysis was an Agilent (Agilent Technologies, India) 7890 gas chromatograph coupled with a 5975-quadrupole mass spectrometer detector. The injector temperature was allowed to remain at 60 ℃ for 2 min, then 25 ℃/min to 100 ℃ for 0 min and then increased linearly to 250 ℃ for 15 min kept constant. To identify intermediate compounds that result from dye degradation, the NIST Research Library was used to compare spectra of the compounds.

Phytotoxicity analysis

The toxicity of biodegradable dye metabolites was determined with seeds of Oryza sativa. The experiment was carried out using the method proposed by Patel and Patel (2020) with some changes. A total of 20 seeds were surface sterilized using sodium hypochlorite, followed by washing with de-ionized water. Afterwards, seeds were grown in a glass Petri dish lined with 2–3 layers of filter paper that was soaked with a solution, prepared as follows: (1) positive control-distilled water; (2) negative control-untreated dye solution and (3) laccase-treated solution. Petri dish containing seeds were incubated at 37 ℃ temperature. The seeds were regularly watered or irrigated when required to keep the filter paper moist with the respective treatment solution. All the experiments were done in triplicates. Seed germination percentage was calculated by the following formula:

After 7 days of different treatment, seedling length (total plumule + radicle lengths) was measured using scale in centimeters. Similarly, vigor index (unit less) calculated by the following formula:

Statistical analysis

Experiments such as screening, decolorization assays, optimization studies, enzymes characterization, and toxicity tests were carried out in triplicate. To analyze the data from the toxicity assay, a one-way ANOVA and a Tukey's post hoc test were used to perform a statistical analysis. Whereas, OVAT optimization and laccase production using low-cost substrates were analyzed statistically using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparison as post hoc test. Graph Pad Prism 5.0 software was used for the statistical analysis, and the significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Isolation and identification of potent laccase producer

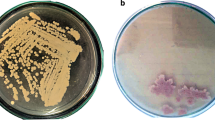

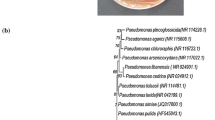

Based on morphological characters, a total of 3 bacterial strains showed laccase production on guaicol agar, whereas only one isolate E1 exhibited ATBS and Syringaldazine substrate oxidation capacity (Fig. 1A–C). The potent true laccase producer isolate E1 was further identified via nucleotide gene sequencing method. The partial amplified 16S rRNA was performed and the resulting sequence (1400 bp) was identified as Stenotrophomonas maltophilia E1. The nucleotide sequence have been submitted to NCBI GenBank with accession number OR342199. The BLAST analysis of the 16S rRNA sequence comparison showed that strain E1 had the most closely related phylogenetic linkage to the genus Stenotrophomonas. The results of phylogenetic analysis indicated that the strain S. maltophilia E1 is closely associated with other strains of Stenotrophomonas (Fig. 1D).

Evaluation of various low-cost substrates for laccase production

Several easily available and cheap agriculture waste residues like sawdust, coconut husk, rice, wheat and barley bran were comparatively examined for production of laccase (Fig. 2). The laccase production was checked at various time interval under the shaking condition. Production of laccase was found higher during the incubation period of 24–48 h. The highest laccase production was noted in the presence of coconut husk (16.7 ± 0.3 IU/mL), followed by wheat bran (14.5 ± 0.2 IU/mL), sawdust (12.4 ± 0.6 IU/mL), rice bran (11.8 ± 0.5 IU/mL), and barley bran (8.2 ± 0.5 IU/mL).

Optimization of laccase production

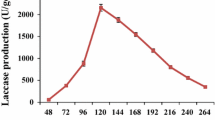

The effect of different factors on the laccase production by S. maltophilia E1 was initially identified through the OVAT method followed by the potential variables study via BBD approach. Result of the OVAT approach displayed that the maximum laccase production (14.9 ± 0.2 IU/mL) was achieved at 36 h incubation time (Fig. 3A), whereas 100 rpm was best suited for maximum laccase (12.6 ± 0.4 IU/mL) production (Fig. 3B). As presented in Fig. 3C, maximum laccase production achieved at 35 ℃ temperature (14.1 ± 0.3 IU/mL) and pH 6 (14.2 ± 0.4 IU/mL) (Fig. 3D).

In this study, the selected parameters such as concentrations of coconut husk, CuSO4, yeast extract, and pH were studied to determine their effect on the laccase production via BBD experiment. The design matrix used for the experiment and summary of the results are presented in Table 2. A total of 29 experimental runs were conducted in flask containing production medium that incubated for 42 h under shaking conditions. The strain E1 exhibited a significant difference (maximum—51.38 ± 1.11 IU/mL; minimum—13.5 IU/mL) in laccase production. Table 2 shows the apparent influence of process variables with respect to their range. To determine the effect of each independent factor, multiple regression analysis was performed, and the following polynomial equation was derived from the regression analysis:

where, Y represents laccase production (IU/mL); A represents concentration of coconut husk; B represents concentration of CuSO4; C represents concentration of yeast extract; and D is the initial pH.

ANOVA analysis was used to determine if the model is suitable for estimating the impact of the numerous variables. This was then tested using Fisher's statistical analysis, which led to the results presented in Table 3. A correlation coefficient of R2 = 0.9902 was found, indicating that the model covered roughly 99.02% of responses, indicating that the experimental and predicted values were related. According to the model F-value and p-value, the model is significant with a F-value of 101.52 and a p-value of < 0.0001. In this case, the F-value of the data was calculated with a 'Lack of Fit' of 2.63, which indicates that the 'Lack of Fit' is also not statistically significant when compared with the pure error. The coefficient of variation (CV) indicates the degree of precision, and it is low (4.62), which means the experiment performed is highly reliable. In this case, a very low probability score (P < 0.05) indicate that model parameters were significant in predicting the response variable.

To better understand the results of the study, a 3D response surface plot is presented in Fig. 4, where it is clear that the theoretical maximum laccase production for each graph is relatively similar to the other graphs. The slope of the response surface provides insight into the interaction of various factors and the relative importance of laccase production. The central point in the counterplots represents the greatest potential for laccase production. Thus, the optimum medium conditions for laccase production were concluded to be 10 mg/L coconut husk concentration, 100 µM CuSO4 concentration, 4.0 mg/L yeast extract concentration, and 6.0 initial pH. In the optimized production medium, the production of laccase reached 51.38 ± 1.11 IU/mL, which is basically consistent with the model predicted theoretical value (51.38 IU/mL).

Effect of pH and temperature

The obtained results revealed the optimal pH value of the crude laccase was 5 towards ABTS, with roughly 40% activity loss at pH 6.0 and 96% activity loss at pH 8.0. Interestingly, the oxidizing activity almost vanished, when the assay pH was raised above 9.0 (Fig. 5A). A temperature of 35 °C was found to be the optimal temperature for crude laccase. A total of about 42% of the total activity was retained, when it was assayed at 45 °C, whereas the oxidizing activity almost completely disappeared, when the assay temperature was raised above 60 °C (Fig. 5B). In case of stability, there was a strong stability in the pH range of 3.0–6.0 during the assay. Furthermore, 60% of the total activity was still present after 6 h of incubation (Fig. 5A). When crude laccase was grown at pH 4.0, the oxidizing activity of crude laccase exhibited superior stability, followed by a constant decline over time. According to the thermal stability test, crude laccase was very stable at temperatures between 25 and 40 °C for 6 h (Fig. 5B). When incubated at 30 ℃, crude laccase showed highest stability. However, it showed a slight decline of oxidizing activity at 35 ℃ with the 56% residual activity.

Dye decolorization and degradation study by crude laccase

Decolorization study by UV–Vis Spectrophotometry

The initial exploration of crude laccase for nine different dyes decolorization was investigated using UV–Vis Spectrophotometry (Table 4). The results shown that crude laccase completely decolorized Malachite green up-to 300 ppm concentration. Whereas, Methyl red, Congo red, and Methyl orange were decolorized 95.4 ± 0.8, 92.6 ± 1.2, and 90.4 ± 1.2 at 100 ppm concentration, respectively. Further, the UV- Vis spectral analysis of untreated Malachite green shown major absorbance peak at 416 nm, which was completely disappear and giving complete decolorization of dyes after 24 h laccase treatment. However, three minor new peaks appeared at 320, 328, and 610 nm (Fig. 6), which indicates the generation of new intermediate metabolites after laccase treatment.

Identification of degraded product analysis by GC–MS

The metabolites formed during Malachite green breakdown were studied by GC–MS. They were identified by comparing the resemblance of their fragment RTs and molecular ions that were similar to those of authentic compounds in the database of NIST library. As shown in Fig. 7A for the mass of untreated Malachite green (329 m/z), the peak disappeared after enzymatic treatment and new peaks were generated (Fig. 7B–F). The intermediates include Michler’s ketone Bis(4-(dimethylamino) phenyl) methanone (267 m/z), 4-(dimethylamino) benzophenone (223 m/z), dibenzylmethane (166 m/z), 4-(dimethylamino) benzaldehyde (145 m/z), and 4-(dimethylamino) phenol (138 m/z) were identified (Fig. 7).

The mass spectra of the degradation products of malachite green by laccase. A malachite green (329 m/z), B Michler’s ketone Bis(4-(dimethylamino) phenyl) methanone (267 m/z), C 4-(dimethylamino) benzophenone (223 m/z), D dibenzylmethane (166 m/z), E 4-(dimethylamino) benzaldehyde (145 m/z), F 4-(dimethylamino) phenol (138 m/z)

Phytotoxicity assay

The toxicity of Malachite green and its laccase mediated decolorization products were performed with O. sativa seeds. The germination index was used as an indicator of phytotoxicity in Petri dishes. The relative sensitivity of O. sativa seeds toward laccase treated and untreated Malachite green solutions are summarized in Table 5. Whereas, germination index of all laccase treated at 100 ppm dye is represented in Table 4. The results of the phytotoxicity study showed about 42.15% inhibition of the germination of O. sativa seeds soaked in the laccase untreated Malachite green. Whereas, laccase-treated Malachite green showed only 4.52% inhibition of the germination of O. sativa seeds compared to control. The seedling lengths of seeds germinated in the untreated dye solution were found to be almost fifteen times lower than those of the seeds germinated in the degradation metabolites (P < 0.05). Whereas, a significant improvement in the seedling length was observed in the extracted decolorization products (Table 4). The vigor index of laccase treated dye solution was comprehensively higher than untreated dye solutions (Table 4).

Discussion

Amlakhadi (India), which has been exposed to a variety of xenobiotics released by industrial effluents for a long period of time. At this type of anthropogenic site, the microbial community plays a significant role in biodetoxification and biotransformation of many toxic compounds (Pathak et al. 2009). Due to the prolong exposure of organic dyes, solvent and other compounds, microorganisms have evolved and adapted which can utilize and detoxify these compounds to survive (Patel et al. 2012). Organic effluents from the dye industries have shown negative impact on the environment, because they are often discharged into water bodies, which are used in irrigation for agricultural purposes (Leo et al. 2019). Moreover, effluents generated from the dye and textile industries contain a wide variety of phenolic, as well as non-phenolic substances that contribute to the growth of laccase producing microbes (Deepa et al. 2020). The role of laccase in various applications including dye decolorizing and detoxification are already established by many researchers (Iark et al. 2019; Leo et al. 2019). Therefore, the main objective of the present study was to isolate the bacterial strains having laccase producing ability, and then applied it for various dye decolorization experiment. For that, initially the bacterial strains were screened on Guaicol agar, and then positive isolates were further screened on ATBS and Syringaldazine substrate to determine the true laccase production ability. The isolate named E1 was successfully passed the screening, and it was identified as Stenotrophomonas maltophilia E1 by 16S rRNA sequencing techniques. Most commonly, white rot fungi produce laccase, but there are also bacteria that can produce laccase (Ben Younes et al. 2021). We believe that the present study is one of the few reports that deal with the screening of bacterial laccases as far as our knowledge. As a result of a literature survey, it was shown that some S. maltophilia E1 strains had been implicated in the production of laccase (Galai et al. 2009; Alaya et al. 2021).

Laccase is an enzyme that can oxidize a wide variety of substrates. This makes it an interesting subject for research on its characteristics and potential uses in industrial processes (Zhu et al. 2016). A robust biotechnological approach for producing extracellular laccase is to induce the production of the enzyme by microbes using agro-residues that are cheap and readily available. In the present study, sawdust, coconut husk, rice, wheat and barley bran were selected for the laccase production in which coconut husk was appeared as best substrate. The literature study shows that wheat bran, wheat straw, rice bran, sawdust, corn, apple pomace, canola roots, sugarcane bagasse, cotton stalk,s etc., were identified as potential agro-residue for laccase production through fungi (Ghosh and Ghosh 2017; Wang et al. 2019). There is a maximum production of laccase by Bacillus aquimaris AKRCo2 (4.58 U/mL), when rice bran was used as a substrate for fermentation (Kumar et al. 2022). A comparison of the laccase production of S. maltophilia E1 and other reported bacterial strains using a cheap source of substrate is presented in Table 6.

There are number of factors that affect the metabolic activity of bacterial cells for laccase production, such as the pH of the initial medium, temperature, and the agitation speed of the medium (Kumar et al. 2022). The various culture medium pH affects the laccase productivity. The bacterial isolate E1 shown maximum laccase production in acidic pH (6.0) condition. It was found that a further rise in pH did not result in an increase in the production of laccase. It can be attributed to the poor growth of the organism at an elevated pH, which may be affecting the production of laccase as a result (Patel and Gupte 2016). Temperature is another significant factor that affects the fermentation process due to bacterial growth and enzyme production being sensitive to temperature. Isolate E1 showed maximum laccase production at 35 ℃ temperature. There is a direct link between higher temperatures and adverse effects on the metabolic activity of microbes, thus causing to the denaturation of enzymes (Desai and Patel 2019; Patel and Dudhagara 2020). However, lower temperature (< 20 ℃) did not support bacterial growth, thus leading to reduced enzyme production (Deepa et al. 2020). Earlier studies suggested that the lower the temperature, the slower the metabolic rate of the bacteria, as well as fungi, which led to the reduction in laccase production. However, some researchers have reported an optimal mesophilic temperature range for laccase production using bacteria and fungi (Patel and Gupte 2016; Wang et al. 2019). As a result, isolates exhibiting optimum laccase production at mesophilic temperatures are always preferred for industrial laccase production (Contesini et al. 2018). Furthermore, agitation speeds affect microbial growth by improving dissolved oxygen in the culture medium, which directly affects enzyme production (Patel and Bhaskaran 2020). A maximum laccase production by isolate E1 was achieved after 24 h of incubation, with a slight decrease on subsequent incubations. The reduction in enzyme production during prolonged incubation might be attributed to the inhibition effect of metabolites secreted by the microbes themselves within the medium during incubation (Mehandia et al. 2020).

The RSM approach was applied for the laccase production which was carried out using four independent variables i.e., coconut husk, CuSO4, yeast extract and initial pH. There was a non-significant value of lack of fit found in the statistical analyses (p > 0.05), and a highly significant level of performance of the model measured at the parameter level (p < 0.0001), which indicates that the mode is capable of being accurately predicted by the variation of the parameters (Prajapati et al. 2021). Moreover, the generated model fit goes very well with the experimental results, which indicates the model was significant. The model presented values for the predicted responses that were very close to the actual values of the experimental responses (Table 2), which is consistent with the result of R2 and R2 –adj (Table 3). The response surface 3D graph plotted from equation (mention above) illustrates the influence of variables along with their interactions (Fig. 4). However, the yield of the laccase production initially increased with lower concentration up-to optimal value, and then after it declines gradually with higher concentration of variables. The substrate coconut husk having high lignin content and first time laccase production capability of white-rot fungus Pycnoporus sanguineus using coconut husk was evaluated by Karim and Annuar (2009). In present study, 10 mg/L coconut husk concentration was observed optimum for laccase production. The CuSO4 was characterized as an inducer for laccase production. According to the Buddhika et al. (2021), in addition to being an essential component of cell growth and laccase gene transcription, copper and its metabolism also play an important role in laccase activity. The nitrogen source yeast extracts support bacterial growth and induce laccase production. Zhu et al. (2016) observed and reported that copper and yeast extract were the most powerful inducers of laccase production in Pleurotus ostreatus (ATCC 52857). pH of the medium plays an important role for the cell growth and laccase production. Generally, acidic pHs are favorable for laccase production for fungi, whereas for bacteria it is generally natural (Chauhan et al. 2017). Our findings showed that isolate E1 produce optimum laccase under acidic condition (pH 6.0). Kuddus et al. (2013) showed higher laccase production at pH 7.0 in P. putida. The optimization study helps to determine exact concentration for maximum product formation which makes process economical.

Enzyme characterization is an important criteria for their application in various fields. Currently fungal laccase is used in majority of biotechnological application. It has been found that the fungal enzymes are able to function efficiently only under slightly acidic conditions (5 > and < 7), while for catalytic activity to occur, a temperature range of 20–35 °C has been found to be most suitable (Abdelgalil et al. 2020). On the other hand, very little is known about bacterial laccase, which has wide substrate specificities that can be utilized in industrial settings (Chandra and Chowdhary 2015). In this study, laccase shown optimum activity at pH—4.0, while remaining stable at pH—5.0. This result is consistent with that attained by Abdelgalil et al. (2020). They tested purified laccase, isolated from Alcaligenes faecalis demonstrating maximum activity at pH—4.0. In contrast to this study, laccase from Anoxybacillus aydernsis showed optimum activity at pH—7.0, and most stable at pH—7.5. The optimum temperature for crude laccase of isolate E1 was 35 ℃, whereas showing higher stability at wide temperature range. The findings of the present study are similar with several previous studies (Singh et al. 2007; Bozoglu et al. 2013).

Additionally, the laccase form the isolate E1 showed decolorization and degradation ability towards different varieties of synthetic dyes that is same as most studied bacterial laccase (Khan et al. 2013; Lončar et al. 2014; Feng et al. 2015; Abdelgalil et al. 2020). Except Crystal violet and Methylene blue, other seven dyes decolorized more than 80% at 100 ppm concentration. Apart from this, Malachite green decolorized 91.8 ± 2.0% at 500 ppm concentration. Therefore, we can conclude that strain E1 laccase can be considered as a potent decolorizing enzyme. The bacterial laccase is capable of oxidizing numerous benzene ring containing compounds, and it plays a crucial role in textile effluent detoxification (Chandra and Chowdhary 2015). It is well established that the gene ‘lac’ codes for the laccase, which is known as the Malachite green degrader (Yang et al. 2015; Alaya et al. 2021). The Michler’s ketone Bis(4-(dimethylamino) phenyl) methanone, 4-(dimethylamino) benzophenone, dibenzylmethane, 4-(dimethylamino) benzaldehyde, and 4-(dimethylamino) phenol were found after malachite green degradation by laccase treatment. Therefore, a possible proposed degradation pathway for the degradation of malachite green by laccase of S. maltophilia E1 is presented in Fig. 8. The result of present study is consistent with previous studies, which also detected these types of metabolites after treating the samples with laccase (Yang et al. 2015; Ghobadi Nejad et al. 2019) and with bacterial degradation (Chen et al. 2009; Du et al. 2011) of Malachite green. A comparison of the degradation of Malachite green by laccase of S. maltophilia E1 and other reported microbial strains is presented in Table 7.

However, to check the toxicity of generated metabolites is an important aspect. The phytotoxicity result revealed that laccase treated Malachite green have higher germination percentage, seedling length and vigor compared to untreated Malachite green. This suggested that laccase mediated degradation reduces the toxicity of Malachite green. However, when compared it with control, slight difference was observed in all three parameters (i.e., germination percentage, seedling length and vigor). Similar to our phytotoxicity assay result, laccase mediated Malachite green degradation reduces the toxicity by improving root elongation rate and seed germination of Phaseolus mungo and Triticum aestivum (Parshetti et al. 2006), Nicotina tabacum and Lactuca sativa (Yang et al. 2015). According to Du et al. (2011), Malachite green degradation by Pseudomonas sp. has been shown to compete and partially eliminate germination inhibition for Medicago sativa and Brassica chinensis.

Overall, results of the present study revealed that S. maltophilia E1 laccase exhibits a capability to degrade Malachite green dye without the requirement of a mediator similarly like other studies (Ghobadi Nejad et al. 2019; Yang et al. 2015), despite the generally lower redox potentials associated with bacterial laccases compared to fungal laccases (Margot et al. 2013). For this, one possibility is that S. maltophilia E1 laccase can directly interact with the dye molecules and transfer electrons to the dye molecules without the need for a mediator. This would suggest a high affinity between the laccase active site and the dye molecules, enabling efficient electron transfer (Arregui et al. 2019). Second, the microenvironment surrounding the enzyme within the bacterial cell may provide conditions conducive to mediator-free reactions. This could include factors such as pH, temperature, presence of specific cofactors or molecules within the cell that enhance the performance of enzyme (Bolivar and Nidetzky 2019). Third, S. maltophilia laccase might utilize alternative electron transfer pathways or cofactors that compensate for its lower redox potential, thereby enabling it to oxidize dyes efficiently without external mediators (Jones and Solomon 2015). Moreover, the structural characteristics of S. maltophilia laccase may differ from typical bacterial laccases, allowing it to interact with dye molecules more effectively. However, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of this phenomenon, further experiments will be needed to conduct in-detail.

Conclusion

In summary, laccase from S. maltophilia E1 was optimized, characterized, and applied for dye decolorization and degradation study. The agro-waste coconut husk emerged as potent substrate for laccase production. The optimized media parameters by BBD improved laccase production three times more than initial unoptimized media. The preferred pH and temperature for crude laccase were 4.0 and 35 ℃, respectively. A crude laccase was also demonstrated to be effective in decolorizing some industrial dyes. In which, laccase effectively decolorized and detoxify Malachite green. Moreover, phytotoxicity data revealed that generated metabolites were less toxic compared to untreated Malachite green. Thus, laccase of S. maltophilia E1 will be a promising enzyme for the removal of Malachite green as well as bioremediation of other dye effluents.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

References

Abdelgalil SA, Attia AR, Reyed RM, Soliman NA (2020) Partial purification and biochemical characterization of a new highly acidic NYSO laccase from Alcaligenes faecalis. J Genet Eng Biotechnol 18:1–11

Agrawal K, Chaturvedi V, Verma P (2018) Fungal laccase discovered but yet undiscovered. Bioresour Bioprocess 5:1–12

Akram F, Ashraf S, Haq Iu, Shah FI, Aqeel A (2022) Eminent industrial and biotechnological applications of laccases from bacterial source: a current overview. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-021-03781-9

Alaya V, Kodi RK, Ninganna E, Gowda B, Shivanna MB (2021) Decolorization of malachite green dye by Stenotrophomonas maltophilia a compost bacterium. Bull Natl Res Cent 45:1–13

Aracri E, Colom JF, Vidal T (2009) Application of laccase-natural mediator systems to sisal pulp: an effective approach to biobleaching or functionalizing pulp fibres? Bioresour Technol 100:5911–5916

Ardila-Leal LD, Poutou-Piñales RA, Pedroza-Rodríguez AM, Quevedo-Hidalgo BE (2021) A brief history of colour, the environmental impact of synthetic dyes and removal by using laccases. Molecules 26:3813

Arregui L, Ayala M, Gómez-Gil X, Gutiérrez-Soto G, Hernández-Luna CE, de Los H, Santos M, Levin L, Rojo-Domínguez A, Romero-Martínez D, Saparrat MC (2019) Laccases: structure, function, and potential application in water bioremediation. Microb Cell Factories 18(1):1–33

Ausec L, Zakrzewski M, Goesmann A, Schlüter A, Mandic-Mulec I (2011) Bioinformatic analysis reveals high diversity of bacterial genes for laccase-like enzymes. PLoS ONE 6(10):e25724

Ben Younes S, Dallali C, Ellafi A, Bouslama L, Feriani A, Sayadi S (2021) Extracellular enzymatic activities of bacterial strains isolated from tunisian biotopes: decolorization and detoxification of indigo carmine. Catal Lett 151:1248–1261

Bisaccia M, Binda E, Rosini E, Caruso G, Dell’Acqua O, Azzaro M, Laganà P, Tedeschi G, Maffioli EM, Pollegioni L (2023) A novel promising laccase from the psychrotolerant and halotolerant Antarctic marine Halomonas sp. M68 strain. Front Microbiol 14:1078382

Blánquez A, Rodríguez J, Brissos V, Mendes S, Martins LO, Ball AS, Arias ME, Hernandez M (2019) Decolorization and detoxification of textile dyes using a versatile Streptomyces laccase-natural mediator system. Saudi J Biol Sci 26:913–920

Bolivar JM, Nidetzky B (2019) The microenvironment in immobilized enzymes: methods of characterization and its role in determining enzyme performance. Molecules 24(19):3460

Bozoglu C, Adiguzel A, Nadaroglu H, Yanmis D, Gulluce M (2013) Purification and characterization of laccase from newly isolated thermophilic Brevibacillus sp. (Z1) and its applications in removal of textile dyes. Res J Biotechnol 8:56–66

Buddhika UVA, Savocchia S, Steel CC (2021) Copper induces transcription of BcLCC2 laccase gene in phytopathogenic fungus, Botrytis cinerea. Mycology 12:48–57

Chandra R, Chowdhary P (2015) Properties of bacterial laccases and their application in bioremediation of industrial wastes. Environ Sci Process Impacts 17:326–342

Chandra R, Kumar V, Yadav S (2017) Extremophilic ligninolytic enzymes. In: Sani RK, Krishnaraj RN (eds) Extremophilic enzymatic processing of lignocellulosic feedstocks to bioenergy. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 115–154

Chauhan PS, Jha B (2018) Pilot scale production of extracellular thermo-alkali stable laccase from Pseudomonas sp. S2 using agro waste and its application in organophosphorous pesticides degradation. J Chem Technol Biotechnol 93(4):1022–1030

Chauhan PS, Goradia B, Saxena A (2017) Bacterial laccase: recent update on production, properties and industrial applications. 3 Biotech 7(5):323

Chen CY, Kuo JT, Cheng CY, Huang YT, Ho IH, Chung YC (2009) Biological decolorization of dye solution containing malachite green by Pandoraea pulmonicola YC32 using a batch and continuous system. J Hazard Mater 172:1439–1445

Chen G, Dong J, Wan J, Ma Y, Wang Y (2021) Fiber characterization of old corrugated container bleached pulp with laccase and glycine pretreatment. Biomass Convers Biorefin. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-020-01200-3

Contesini FJ, de Melo RR, Sato HH (2018) An overview of Bacillus proteases: from production to application. Crit Rev Biotechnol 38:321–334

Dai S, Yao Q, Yu G, Liu S, Yun J, Xiao X, Deng Z, Li H (2021) Biochemical characterization of a novel bacterial laccase and improvement of its efficiency by directed evolution on dye degradation. Front Microbiol 12:633004

de Souza Vandenberghe LP, Junior NL, Valladares-Diestra KK, Karp SG, Siqueira JGW, Rodrigues C, Soccol CR (2022) Enzymatic bioremediation: current status, challenges, future prospects, and applications. In: Rodriguez-Couto S, Shah MP (eds) Development in wastewater treatment research and processes. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 355–381

Deepa T, Gangwane AK, Sayyed RZ, Jadhav HP, Mehjabeen, (2020) Optimization and scale-up of laccase production by Bacillus sp. BAB-4151 isolated from the waste of the soap industry. Environ Sustain 3:471–479

Desai M, Patel K (2019) Isolation, optimization, and purification of extracellular levansucrase from nonpathogenic Klebsiella strain L1 isolated from waste sugarcane bagasse. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol 19:101107

Du L-N, Wang S, Li G, Wang B, Jia XM, Zhao YH, Chen YL (2011) Biodegradation of malachite green by Pseudomonas sp. strain DY1 under aerobic condition: characteristics, degradation products, enzyme analysis and phytotoxicity. Ecotoxicology 20:438–446

Feng S, Su Y, Dong M, He X, Kumaresan D, O’Donnell AG, Wu J, Chen X (2015) Laccase activity is proportional to the abundance of bacterial laccase-like genes in soil from subtropical arable land. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 31:2039–2045

Ferrer M, Beloqui A, Golyshin PN (2010) Screening metagenomic libraries for laccase activities. Metagenomics Methods Protocol. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-60761-823-2_13

Galai S, Limam F, Marzouki MN (2009) A new Stenotrophomonas maltophilia strain producing laccase. Use in decolorization of synthetics dyes. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 158:416–431

Ghobadi Nejad Z, Borghei SM, Yaghmaei S (2019) Biodegradation of synthetic dye using partially purified and characterized laccase and its proposed mechanism. Int J Environ Sci Technol 16:7805–7816

Ghosh P, Ghosh U (2017) Statistical optimization of laccase production by Aspergillus flavus PUF5 through submerged fermentation using agro-waste as cheap substrate. Acta Biol Szeged 61:25–33

Gomare SS, Parshetti GK, Govindwar SP (2009) Biodegradation of malachite green by Brevibacillus laterosporus MTCC 2298. Water Environ Res 81(11):2329–2336

Iark D, dos Reis Buzzo AJ, Garcia JAA, Correa VG, Helm CV, Correa RCG, Peralta RA, Moreira RDFPM, Bracht A, Peralta RM (2019) Enzymatic degradation and detoxification of azo dye Congo red by a new laccase from Oudemansiella canarii. Bioresour Technol 289:121655

Jawale JP, Nandre VS, Latpate RV, Kulkarni MV, Doshi PJ (2021) Isolation, characterization and optimizations of laccase producer from soil: a comprehensive study of application of statistical approach to enhance laccase productivity in Myrothecium verrucaria NFCCI 4363. Bioresour Technol Rep 15:100751

Jones SM, Solomon EI (2015) Electron transfer and reaction mechanism of laccases. Cell Mol Life Sci 72:869–883

Karim MAA, Annuar MSM (2009) Novel application of coconut husk as growth support matrix and natural inducer of fungal laccase production in a bubble column reactor. Asia Pac J Mol Biol Biotechnol 17:47–52

Khan R, Bhawana P, Fulekar MH (2013) Microbial decolorization and degradation of synthetic dyes: a review. Rev Environ Sci Bio/technology 12:75–97

Kuddus M, Joseph B, Ramteke PW (2013) Production of laccase from newly isolated Pseudomonas putida and its application in bioremediation of synthetic dyes and industrial effluents. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol 2:333–338

Kumar A, Singh AK, Bilal M, Chandra R (2022) Sustainable production of thermostable laccase from agro-residues waste by Bacillus aquimaris AKRC02. Catal Lett 152(6):1784–1800

Leo VV, Passari AK, Muniraj IK, Uthandi S, Hashem A, AbD-Allah EF, Alqarawi AA, Singh BP (2019) Elevated levels of laccase synthesis by Pleurotus pulmonarius BPSM10 and its potential as a dye decolorizing agent. Saudi J Biol Sci 26:464–468

Lončar N, Gligorijević N, Božić N, Vujčić Z (2014) Congo red degrading laccases from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strains isolated from salt spring in Serbia. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad 91:18–23

Maalej-Kammoun M, Zouari-Mechichi H, Belbahri L, Woodward S, Mechichi T (2009) Malachite green decolourization and detoxification by the laccase from a newly isolated strain of Trametes sp. Int Biodeterior Biodegr 63(5):600–606

Mandic M, Djokic L, Nikolaivits E, Prodanovic R, O’Connor K, Jeremic S, Topakas E, Nikodinovic-Runic J (2019) Identification and characterization of new laccase biocatalysts from Pseudomonas species suitable for degradation of synthetic textile dyes. Catalysts 9:629

Margot J, Bennati-Granier C, Maillard J, Blánquez P, Barry DA, Holliger C (2013) Bacterial versus fungal laccase: potential for micropollutant degradation. AMB Express 3:1–14

Mate DM, Alcalde M (2015) Laccase engineering: from rational design to directed evolution. Biotechnol Adv 33(1):25–40

Mehandia S, Sharma SC, Arya SK (2020) Isolation and characterization of an alkali and thermostable laccase from a novel Alcaligenes faecalis and its application in decolorization of synthetic dyes. Biotechnol Rep 25:e00413

Mukherjee T, Das M (2014) Degradation of malachite green by Enterobacter asburiae strain XJUHX-4TM. Clean Soil Air Water 42(6):849–856

Muthukumarasamy NP, Jackson B, Joseph Raj A, Sevanan M (2015) Production of extracellular laccase from Bacillus subtilis MTCC 2414 using agroresidues as a potential substrate. Biochem Res Int. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/765190

Nguyen LN, Vu MT, Johir MAH, Pathak N, Zdarta J, Jenionowski T, Semblante GU, Hai FI, Khanh Dieu Nguyen H, Nghiem LD (2020) A novel approach in crude enzyme laccase production and application in emerging contaminant bioremediation. Processes 8:648

Parshetti G, Kalme S, Saratale G, Govindwar S (2006) Biodegradation of malachite green by Kocuria rosea MTCC 1532. Acta Chim Slov 53:492

Patel H, Gupte A (2016) Optimization of different culture conditions for enhanced laccase production and its purification from Tricholoma giganteum AGHP. Bioresour Bioprocess 3:1–10

Patel RJ, Bhaskaran L (2020) Orange peel as an inducer for Laccase production in a novel fungal strain peyronellaea pinodella BL-3/4 and optimization of its cultural parameters by single parameter approach. Indian J Sci Technol 13:1656–1667

Patel K, Dudhagara P (2020) Optimization of xylanase production by Bacillus tequilensis strain UD-3 using economical agricultural substrate and its application in rice straw pulp bleaching. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol 30:101846

Patel K, Patel M (2020) Improving bioremediation process of petroleum wastewater using biosurfactants producing Stenotrophomonas sp. S1VKR-26 and assessment of phytotoxicity. Bioresour Technol 315:123861

Patel H, Gupte A, Gupte S (2009) Effect of different culture conditions and inducers on production of laccase by a basidiomycete fungal isolate Pleurotus ostreatus HP-1 under solid state fermentation. BioResources 4:268–284

Patel V, Cheturvedula S, Madamwar D (2012) Phenanthrene degradation by Pseudoxanthomonas sp. DMVP2 isolated from hydrocarbon contaminated sediment of Amlakhadi canal, Gujarat, India. J Hazard Mater 201:43–51

Pathak H, Kantharia D, Malpani A, Madamwar D (2009) Naphthalene degradation by Pseudomonas sp. HOB1: in vitro studies and assessment of naphthalene degradation efficiency in simulated microcosms. J Hazard Mater 166:1466–1473

Pham VHT, Kim J, Chang S, Bang D (2023) Investigating bio-inspired degradation of toxic dyes using potential multi-enzyme producing extremophiles. Microorganisms 11(5):1273

Prajapati J, Dudhagara P, Patel K (2021) Production of thermal and acid-stable pectinase from Bacillus subtilis strain BK-3: optimization, characterization, and application for fruit juice clarification. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol 35:102063

Rodríguez-Escribano D, De Salas F, Pardo I, Camarero S (2017) High-throughput screening assay for laccase engineering toward lignosulfonate valorization. Int J Mol Sci 18(8):1793

Rueda-Villabona JD, Rueda AM, Saavedra OL, Hernandez I, Rincon G, Martinez-Vega RA, Sanxhez CI (2021) Crude enzymatic extract from Dictyopanus pusillus LMB4 as a biotechnological tool for crystal violet biodegradation. Bioresour Technol Rep 15:100723

Sarnaik A, Liu A, Nielsen D, Varman AM (2020) High-throughput screening for efficient microbial biotechnology. Curr Opin Biotechnol 64:141–150

Selvam K, Ameen F, Amirul Islam M, Sudhakar C, Selvankumar T (2022) Laccase production from Bacillus aestuarii KSK using Borassus flabellifer empty fruit bunch waste as a substrate and assessing their malachite green dye degradation. J Appl Microbiol 133(6):3288–3295

Shanmugam S, Ulaganathan P, Swaminathan K, Sadhasivam S, Wu Y-R (2017) Enhanced biodegradation and detoxification of malachite green by Trichoderma asperellum laccase: degradation pathway and product analysis. Int Biodeter Biodegr 125:258–268

Shin SK, Hyeon JE, Joo YC, You SK, Han SO (2019) Effective melanin degradation by a synergistic laccase-peroxidase enzyme complex for skin whitening and other practical applications. Int J Biol Macromol 129:181–186

Singh D, Gupta N (2020) Microbial laccase: a robust enzyme and its industrial applications. Biologia (bratisl) 75:1183–1193

Singh G, Capalash N, Goel R, Sharma P (2007) A pH-stable laccase from alkali-tolerant γ-proteobacterium JB: purification, characterization and indigo carmine degradation. Enzyme Microb Technol 41:794–799

Sondhi S, Saini K (2019) Response surface based optimization of laccase production from Bacillus sp. MSK-01 using fruit juice waste as an effective substrate. Heliyon 5:e01718

Thapa S, Mishra J, Arora N, Mishra P, Li H, O’hair J, Bhatti S, Zhou S (2020) Microbial cellulolytic enzymes: diversity and biotechnology with reference to lignocellulosic biomass degradation. Rev Environ Sci Bio/Technol 19:621–648

Thoa LTK, Thao TTP, Hung NB, Khoo KS, Quang HT, Lan TT, Hoang VD, Park S-M, Ooi CW, Show PL (2022) Biodegradation and detoxification of malachite green dye by extracellular laccase expressed from Fusarium oxysporum. Waste Biomass Valori 13(5):2511–2518

Unuofin JO, Okoh AI, Nwodo UU (2019) Maize stover as a feedstock for enhanced laccase production by two gammaproteobacteria: a solution to agroindustrial waste stockpiling. Indus Crops Prod 129:611–623

Uthandi S, Saad B, Humbard MA, Maupin-Furlow JA (2010) LccA, an archaeal laccase secreted as a highly stable glycoprotein into the extracellular medium by Haloferax volcanii. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:733–743

Wang F, Xu L, Zhao L, Ding Z, Ma H, Terry N (2019) Fungal laccase production from lignocellulosic agricultural wastes by solid-state fermentation: a review. Microorganisms 7:665

Wilson K (2001) Preparation of genomic DNA from bacteria. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471142727.mb0204s56

Yang J, Yang X, Lin Y, Ng TB, Lin J, Ye X (2015) Laccase-catalyzed decolorization of malachite green: performance optimization and degradation mechanism. PLoS ONE 10:e0127714

Yang J, Li W, Ng TB, Deng X, Lin J, Ye X (2017) Laccases: production, expression regulation, and applications in pharmaceutical biodegradation. Front Microbiol 8:832

Zhu C, Bao G, Huang S (2016) Optimization of laccase production in the white-rot fungus Pleurotus ostreatus (ACCC 52857) induced through yeast extract and copper. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip 30:270–276

Zhu D, Qaria MA, Zhu B, Sun J, Yang B (2022) Extremophiles and extremozymes in lignin bioprocessing. Renew Sust Energy Rev 157:112069

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to acknowledge Scientific Research Deanship at University of Ha’il-Saudi Arabia for funding this work through project number BA-22018.

Funding

This research has been funded by Scientific Research Deanship at University of Ha’il-Saudi Arabia through project number BA-22018.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MP and YA contributed to study concept and design, collected/analyzed data, project administration and drafted the original manuscript. MA, AJ, MS, KP contributed to methodology, data curation, investigation, visualization, analysis, review and editing; MA, YA and MP contributed to critical revision of the manuscript, methodology, validation, formal analysis and study supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Albulaihed, Y., Adnan, M., Jamal, A. et al. Optimization of laccase from Stenotrophomonas maltophilia E1 by submerge fermentation using coconut husk with its detoxification and biodecolorization ability of synthetic dyes. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 10, 80 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40643-023-00703-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40643-023-00703-x