Abstract

Bacterioruberin and its rare glycosylated derivatives are produced by Arthrobacter agilis as an adaptation strategy to low temperature conditions. The high antioxidant properties of bacterioruberin held great promise for different future applications like the pharmaceutical and food industries. Microbial production of bacterioruberin via a cost-effective medium will help increase its commercial availability and industrial use. The presented study aims to optimize the production of the rare C50 carotenoid bacterioruberin and its derivatives from the psychotrophic bacteria Arthrobacter agilis NP20 strain on a whey-based medium as a cost effective and readily available nutritious substrate. The aim of the study is extended to assess the efficiency of whey treatment in terms of estimating total nitrogen content in treated and untreated whey samples. The significance of medium ingredients on process outcome was first tested individually; then the most promising factors were further optimized using Box Behnken design (BBD). The produced carotenoids were characterized using UV–visible spectroscopy, FTIR spectroscopy, HPLC–DAD chromatography and HPLC-APCI-MS spectrometry. The maximum pigment yield (5.13 mg/L) was achieved after a 72-h incubation period on a core medium composed of 96% sweet whey supplemented with 0.46% MgSO4 & 0.5% yeast extract and inoculated with 6% (v/v) of a 24 h pre-culture (109 CFU/mL). The cost of the formulated medium was 1.58 $/L compared with 30.1 $/L of Bacto marine broth medium. The extracted carotenoids were identified as bacterioruberin, bis-anhydrobacteriouberin, mono anhydrobacterioruberin, and glycosylated bacterioruberin. The presented work illustrates the possibility of producing bacterioruberin carotenoid from Arthrobacter agilis through a cost-effective and eco-friendly approach using cheese whey-based medium.

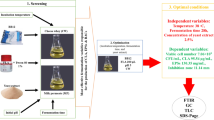

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently, environmental and health-related worries about the hazards of synthetic colorants have sparked interest in finding natural alternative dyes, especially for food and cosmetic applications (Celedón and Díaz 2021). In response to this, an upsurge in the demand for natural dyes has been noticed in the past few years to replace synthetic ones (Yusuf et al. 2017). Although microorganisms produce pigments in multiple elegant shades with different bioactivities like anticancer, antioxidant antimicrobial, and UV-protective properties (Silva et al. 2014; Agarwal et al. 2023), microbial-based pigments have not been widely used in several industries due to the lack of commercial availability. Successful implementation of microbial cell factories for the sustainable production of natural carotenoids can be achieved by making them economically competitive with synthetic ones. The cost of the nutritional medium used to grow the microorganisms is one of the main obstacles that hinders large-scale production of microbial-based pigments (Aman Mohammadi et al. 2022). To overcome this obstacle, many efforts have been directed towards utilizing low-cost substrates to provide the necessary elements for microbial growth. Biomasses produced from the processing of agricultural and food products are highly rich in carbohydrates, proteins, vitamins, and minerals. However, most of these wastes are not optimally used and cause environmental pollution (Jin et al. 2018). Recycling these wastes into value-added products like bio pigments is a sustainable approach to satisfying the increasing needs of bio-colors and would help strengthen the circular economy concept (Usmani et al. 2020). Many agri-food by-products such as fruit pomace, seeds, peels, corn steep liquor, molasses, whey, bran, etc. have been utilized as possible fermentable substrates to produce bio-pigments using bacteria, yeast, fungi, and algae. For instance, corn steep liquor and preboiled rice water were used as food waste substrates to produce β-carotene using Sporidiobolus pararoseus (Valduga et al. 2014). Prodigiosin was produced from Serratia marcescens using rice bran as a substrate (Arivizhivendhan et al. 2018).

Bacterioruberin pigment is among the rare carotenoids produced exclusively by a limited number of microorganisms. It’s a bright red pigment, classified as C50 carotenoids, formed from an isoprenoid chain with 13 conjugated C = C units and four functional OH-groups arising terminally (Dummer et al. 2011; Yang et al. 2015). The long conjugated double bond system of bacterioruberin has contributed to its superior antioxidant properties compared to β-carotene, which comprises only nine conjugated double bonds (Maia et al. 2021). The high antioxidant capacity of bacterioruberin makes it a promising ingredient in pharmaceutical (Hou and Cui 2018; Rodrigo-Baños et al. 2015) and cosmeceutical products like anti-ageing and sunscreen formulations (Nichols and Katiyar 2010; Galasso et al. 2017).

Bacterioruberin was reported to play an adaptive role in producing microorganisms. It is produced in a stress-dependent manner under harsh conditions such as high salt content or low temperature conditions (Sutthiwong et al. 2014). For instance, Bacterioruberin carotenoid and its derivatives are the main carotenoids of Haloarchaea that grow optimally in hypersaline environments with an approximate salt concentration of 25–30% (w/v) (Giani et al. 2019). It was proven that bacterioruberin helps this group of archaea thrive under hypersaline conditions by acting as a rivet, allowing the permeability of oxygen and other molecules and preventing water passage (Abbes et al. 2013). On the other hand, bacterioruberin is produced in a temperature-dependent manner in two psychrophilic species of the Arthrobacter genus, Arthrobacter agilis and A. bussei, (Flegler et al. 2020; Fong et al. 2001a). Recent studies have confirmed the role of bacterioruberin and its glycosylated derivatives in improving membrane fluidity at low temperatures and reducing the freezing–thawing effect on bacterial membranes (Flegler and Lipski 2021, 2022a).

It is noteworthy to highlight that the glycosylated derivatives of bacterioruberin are specifically produced in Arthrobacter sp. to cope up with its role in cold adaptation, since carotenoid glycosides are found to cluster in rigid patches, increasing the local rigidity of the membrane to resist the effect of low temperature (Chen et al. 2021; Mohamed et al. 2005; Várkonyi et al. 2002). Glycosylated carotenoids are of high industrial value since glycosylation enhances the solubility, photo-stability, bioavailability, and biological activities of the produced carotenoids (Chen et al. 2021). The quality of carotenoids produced by Arthrobacter sp. makes it a favorable source of bacterioruberin carotenoids compared to the Haloarchaea group.

In this context, the introduced research focuses on producing the rare C50 bacterioruberin carotenoid and its derivatives via a cost-effective and eco-friendly way from Arthrobacter agilis using a whey-based medium. The medium composition was optimized via the response surface methodology (RSM) approach. The work is extended to characterize the produced pigments and test their antioxidant capacity. To the best of our knowledge, the presented research is the first to handle bacterioruberin production from Arthrobacter agilis using a waste-based medium.

Material and methods

Growth media

PY medium (10 g L−1 peptone, 5 g L−1 yeast extract, 5 g L−1 NaCl) was used in isolation step. PA is the solidified form of PY medium using 1.5% agar. Cheese-whey-based medium (96% sweet-whey, 0.46% MgSO4, 0.5% yeast extract) was used as the optimized medium for carotenoid production.

Sweet whey was kindly supplemented from the faculty of Agriculture, Alexandria University.

Isolation, identification of carotenoid producing strain

Isolation step was carried out from air and soil samples. Isolation from air was carried out through settle plate technique, in which sterile PA plates were exposed to air for 15 min then the plates were incubated at 25 °C. Among the grown colored colonies, a pink pigmented one was picked up, purified, and stored at − 20 °C in 15% glycerol.

The selected strain was examined morphologically and microscopically. In addition, the strain was subjected to molecular identification through amplifying 16SrRNA encoding gene according to the previously reported method (Eden et al. 1991). Genomic DNA was extracted using quick DNA miniprep kit (D3024, ZYMO), according to manufacturer’s instructions. The whole length of 16SrRNA gene was amplified through polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the universal primers F27, R1492. The sequence of the purified PCR product was determined via the automated fluorescent DNA sequencer. The obtained nucleotide sequence was analyzed using BLAST n tool offered by NCBI, and the phylogenetic analysis was carried out using MEGA X software to determine the taxonomic affiliation of the isolate.

Pigment extraction and quantification

Fresh activated colonies were picked up for inoculating 20 mL PY medium, the culture was incubated for 24 h at 25 °C. An inoculum of 5% of the grown preculture used to inoculate 100 mL fresh PY medium sterilized in 250 mL flask and incubated at 25 °C for 72 h. At the end of the incubation period, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4 °C for 10 min at 10,000 rpm. Cell pellets were suspended and soaked in methanol for 2 h until complete bleaching of the cells. The extract was centrifuged at 4 °C for 10 min at 10,000 rpm for removing residual cells, wrapped with aluminum foil for light protection, and then stored in − 20 °C.

The extracted pigment was scanned in a wavelength region of 200–800 nm. Total carotenoid concentration in the methanolic extract was determined at the obtained maximum wavelength (λ490) through applying an average extension coefficient (Liaaen-Jensen and Jensen 1971).

Correlation of growth pattern and pigment synthesis of Arthrobacter agilis NP20

To determine maximum production time of the pigment, pigment synthesis was correlated to dry weight over 5 days. The isolate was allowed to grow in PY medium as illustrated previously. At constant time intervals, a suitable culture volume was harvested by centrifugation, pigment was extracted and quantified from the obtained cell pellets as mentioned before, and finally the remaining cell mass was dried at 70 °C until reaching a constant weight.

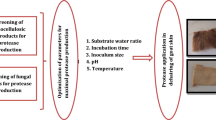

Optimization of C50 carotenoid production on whey-based medium

The capability of the isolate for pigment production was tested on whey-based medium. The basal medium (nominated as Medium 1) is composed of 50% sweet-whey, 0.5% yeast extract and inoculated with 5% of a pre-culture of the same composition. One factor at a time approach was applied to assess the significance of MgSO4, NH4Cl, and KH2PO4 on process outcome. A concentration of 1% of MgSO4, NH4Cl, and KH2PO4 was added individually to medium 1, constituting medium 2, 3, and 4, respectively. In addition, the significance of omitting yeast extract from medium composition was also assessed (Medium 5). In each trial, pigment concentration and cell dry weight were estimated to evaluate the impact of each variable. All trials were carried out in triplicates at 20 °C and 200 rpm for 72 h incubation time. Significant difference was considered at P-value ≤ 0.05 according to the overlapping rule of standard error bars reported by Cuming et al. (Cumming et al. 2007).

The most significant variables were subjected to further optimization step using RSM to estimate their optimal values besides determining the significant interactions between them. In this context, the three selected variables MgSO4% (X1), cheese-whey % (v/v) (X2), inoculum size % (v/v) (X3) were considered to BBD analysis each variable was tested at low (− 1) middle (0) and high level (+ 1) in terms of coded values.

Experimental trials were carried out in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask with a working volume of 30 mL. All trials were incubated at 20 °C, 200 rpm, for 72 h.

RSM determines all possible interactions of the involved independent variables via second-order polynomial equation. The three independent variables of this study are presented by the following equation:

where, Y is the predicted response, β0 is constant, β1, β2, and β3 are linear coefficients, β12, β13, and β23 are cross product coefficients, and β11, β22, and β33 are quadratic coefficients.

Data analysis

The JMP tool was used to run multiple linear regressions on the pigment production data to estimate t-values, p-values, and confidence levels. The p-values were reported as percentages. The significance level was assessed using the Student t test (p-value). The t test for every specific impact allows one to determine how likely it is that the observed effect was discovered accidentally. If the probability of the test variable is low enough, it will be acceptable. The p-value is represented as a percentage by the confidence level. The STATISTI CA 7.0 programme created three-dimensional and contour plots to show the simultaneous effects of the three most significant independent factors on each response.

Model verification

The optimum conditions found through optimization trials were put to the test empirically and contrasted with the results of the model. To prove the accuracy of the model, the model % error was calculated from the following formula:

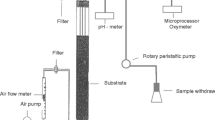

Determination of nitrogen content in the utilized whey before and after treatment.

The total nitrogen content in treated and untreated whey samples was assessed using Kjeldahl method with some modifications. Briefly, 20 mL of H2SO4 and a Kjeldahl tablet was added to 2 mL of both treated and untreated whey samples, separately. The reaction content was burned to 450 °C until it changed into a clear blue green color. After cooling, it was given a quick stir before receiving 200 mL of distilled water and 80 mL of a potassium sulfide-containing NaOH solution. It was associated with the distillation process in this way. On the opposite side of the apparatus, 25 mL of a 3% boric acid solution with Congo red as an indicator were dropped. The nitrogen ratio was computed after the distillation operation was completed and titrated using 0.1 N NaOH solution.

Chromatographic analysis for carotenoid identification

The extracted carotenoids were characterized by UV–visible spectroscopy, FTIR spectroscopy, HPLC–DAD chromatography and HPLC-APCI-MS spectrometry.

In FTIR analysis, the methanolic extract of the carotenoids was applied to salt cuvette and analyzed by FTIR spectroscopy (Perkin Elmer, Germany). The device spectral range was adjusted between 450 and 4000 cm−1.

For HPLC chromatography, a volume of 100 µL of the prefiltered pigment extract was injected into C18 reversed phase column (250 mm × 4.5 mm, 5 µm, Phenomenex, USA). Separation of carotenoids was achieved using two solvent systems, solvent A (H2O: MeOH (1:9 v/v)), and solvent B (EtOAc: MeOH (1:9 v/v)). The elution was carried out gradually; where solvent B concentration was raised from 0 to 100% over 30 min. Eluted peaks were detected using PDA detector in the range 200–600 nm, while the chromatogram was built up at 490 nm. In addition, pigment composition was further investigated via mass spectrometry, the mass spectrum was determined in the range of 200–3000 m/z using the positive ionization mode. Carotenoids identification was determined through comparing the fraction retention time and the characteristics of both UV and mass spectra.

Antioxidant effect

The antioxidant power of Arthrobacter agilis NP20 carotenoids was assessed through free radical scavenging activity (RSA) using DPPH, and the RSA efficiency was compared to β-carotene standard. The assay was applied according to the method previously mentioned (Jiménez-Escrig et al. 2000). Briefly, different concentration of the extracted carotenoids (1.5, 5 and 7 µg) and a concentration of 50 µg of β-carotene standard were tested for their antioxidant efficacy. The samples were diluted to 350 µL with methanol and mixed with 1 mL of 100 µM DPPH. The negative control test was prepared by adding 350 µL of absolute methanol to 1 mL of DPPH. The reactions were incubated at room temperature and the discoloration of DPPH was monitored at wavelength 580 nm along 40 min.

The RSA scavenging efficiency was calculated according to Eq. 2:

Results

Isolation and identification of the red pigmented isolate

The isolation step has resulted in 3 carotenoid producing isolates of different hue colors. However, due to the scarcity of naturally synthesized red carotenoids, red pigmented isolate was selected for further study. On PA medium, colonies appeared smooth, rounded, with reddish pink color with noticeable color darkness after storage at 4 °C (Fig. 1A). Cells of Arthrobacter agilis appeared cocci under the microscope (Fig. 1B).

Identification of Arthrobacter agilis strain NP20 A Phenotypic characterization of colony morphology showing Pink pigmented colonies grown on PY medium B cell morphology under the microscope showing cocci-shaped cells C Phylogenetic analysis using Maximum likelihood method for estimating the relatedness of Arthrobacter agilis NP20 and closely related bacteria. The accession number is displayed by each genus. Bootstrap values are displayed as a percentage of 500 replicates. Escherichia coli was used as an outgroup

Analysis of 16SrRNA sequence revealed that the isolate is affiliated to Arthrobacter agilis (Fig. 1C). The bacterium was nominated as Arthrobacter agilis NP20 and deposited in GenBank under accession number (MT645499).

Production and identification of red carotenoid

The UV/VIS spectrum of pigment methanolic extract showed a characteristic 3 fingered maxima distinctive to C50 carotenoids with maximum absorption at 490 nm (Fig. 2B).

Production and extraction of red pigment carotenoid from Arthrobacter agilis NP20. A Biomass and pigment accumulation pattern of NP20 strain cultivated on whey-based medium along 5 days of incubation B Visible spectrum of the extracted pigment showing the typical (three fingered) maxima of red carotenoids with maximum absorbance around 500 nm

To estimate maximum production time of NP20 carotenoids, the production pattern was related to the strain growth curve in terms of biomass accumulation (Fig. 3A). As illustrated in Fig. 3A, pigment accumulation pattern typically follows the growth pattern of the isolate, where pigment production increased gradually from the onset of log phase and reached its maximum value at the end of the stationary phase. After 72 h, the strain entered a decline phase which displayed a noticeable drop in pigment content due to pigment leakage outside dead cells.

Effect of changing medium ingredients on pigment and biomass yield. Medium 1 consists of 50% whey and 0.5% yeast extract. Medium 2: 1% NH4Cl added to medium1, Medium 3: 1% KH2PO4 added to medium1, Medium 4: 1%MgSO4 added to medium 1, Medium 5: 50% Sweet. All trials were carried out in triplicates at 20 °C. The significant difference was considered according to the overlapping rule at P-value ≤ 0.05. (Cuming et al. 2007)

Optimization of Arthrobacter agilis NP20 pigment production using BBD

Among the added supplements tested initially (Fig. 3), only medium 2 showed a significant increase in both pigment and biomass accumulation. The omission of 0.5% of yeast extract from medium composition (medium 5) severely affected the process outcome (Fig. 3). However, higher concentrations of yeast extract negatively affected pigment accumulation (data not shown).

Based on the obtained results, a fixed concentration of yeast extract was used, while the optimal concentration of both MgSO4% (X1) and whey % (X2) along with the inoculum size % (X3) were further tested using BBD.

The variables were screened at three encoded levels, − 1, 0, 1 in a collective matrix of 15 trials. Table1 shows the designed matrix, real variables levels and the response of each trial in terms of pigment concentration (mg/L) quantified at 490 nm.

Model significance was inferred from P-value (0.056) and F value (4.1) displayed by ANOVA analysis (Table 2). The small regression value (P = 0.056) proves the accuracy of the model in elucidating the relationship between the response and the involved independent variables. The value of R2 was 0.8897 indicating a high degree of association between the predicted and experimental values. Actual by predicted plot for the measured response (pigment conc. (mg/L)) is shown in (Additional file 1: Fig. S1), where a regression line is to minimize the sum of residuals. The multiple linear regression models describe the relationship between the pigment production level and three studied variables namely, MgSO4, whey % and the inoculum size %. Surface plots (Fig. 4) show the variables interaction and contour analyses in plots were calculated to detect the centre point which gives maximum production.

The obtained response results were integrated in a second-order polynomial equation to determine the exact value of each variable and to predict the maximum pigment concentration. The built equation (Eq. 3) includes all possible forms of interactions:

Differentiating the polynomial equation revealed optimal variable values to be (X1 = 0.86), (X2 = 0.96), and (X3 = − 0.80) in terms of coded values to yield 5.13 mg/L as maximum predicted pigment yield (Fig. 5).

A verification experiment was run under the previously obtained anticipated optimal condition to assess the quadratic polynomial's accuracy. The percent error formula was determined as the absolute value of the difference of the measured value and the actual value divided by the actual value and multiplied by 100.

The measured pigment level of NP20 strain was 6.01 mg/L; this means that the calculated model percentage error [(6.01–5.13)/5.13]*100 was ~ 17%.

Determination of nitrogen content in whey before and after treatment

According to Kjeldahl method, the total nitrogen content in the untreated sample recorded 0.56% while the value reduced to 0.14% after microbial treatment using the optimized conditions mentioned above.

Analysis and characterization of the extracted carotenoids

Structure determination of the extracted pigment was carried out using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC–MS). The FTIR analysis (Fig. 6A) showed fingerprint peak at 1650 cm−1corresponding to C = C alkene stretching, indicating the existence of an aliphatic group in pigment extract; in addition, a peak at 1456 cm−1 corresponds to CH2 stretching frequency. While peaks at 1388 and 1159 cm−1 correspond to C–H and C–OH stretching frequencies, respectively.

According to the HPLC elution conditions mentioned previously, the methanolic extract of the pigment was separated into 7 fractions (Fig. 6B). Each peak was identified based on the wavelength maxima and the MS analysis (Table 3). The detected carotenoids belong to Bacterioruberin and its derivatives.

Antioxidant activity of Arthrobacter agilis NP20 carotenoid

DPPH assay was used to assess the antioxidant activity of Arthrobacter agilis NP20 carotenoids. The three different concentrations of the extracted carotenoids showed a positive response with an increase in RSA% with increasing carotenoids concentration (Fig. 7A). The scavenging efficiency of NP20 carotenoids was higher than β-carotene standard. A concentration of 50 µg of β-carotene achieved a maximum RSA (12%) after 40 min, while a concentration of 7 µg of NP20 carotenoids achieved 54% (RSA %) after the same incubation time (Fig. 7B).

Radical scavenging efficiency of Arthrobacter agilis NP20 carotenoids along 40 min. A Radical scavenging activity of three concentrations of NP20 carotenoids, 1.4, 3 and 7 µg. B Radical scavenging activity of 7 µg NP 20 carotenoids compared to 50 µg β-carotene. All trials were measured at 580 nm. All trials were carried out in triplicates and values are expressed as mean ± standard error values

Discussion

In the light of the growing demand for developing novel, risk-free, quickly biodegradable, and environmentally friendly coloring agents, microbial carotenoids have gained a great interest as an important class of bio-pigments (Mussagy et al. 2019). Carotenoids have been proven as potent antioxidant and anticancer agents, in addition, many of them including zeaxanthin and lutein, protect the eyes from cataracts and macular degeneration (Jaswir et al. 2011; Mrowicka et al. 2022). Due to their biological characteristics and possible advantages for human health, many carotenoids are currently employed as natural colorants for food, dietary supplements and nutraceuticals for pharmacological and aesthetic applications (Ashokkumar et al. 2022; Guleria et al. 2017; Gupta et al. 2022).

Bacterioruberin and its derivatives have a unique structure among the known microbial carotenoids. The structure harbors 13 conjugated double bonds distributed within a 50-carbon skeleton, that rendered it a highly potent antioxidant molecule compared to other carotenoids (Jehlička and Oren 2013; Yatsunami et al. 2014). They have a superior activity in reducing the damage of H2O2 exposure, UV and gamma irradiation (Singh and Gabani 2011; Saito et al. 1997). Owing to their antioxidant potentiality, they are found as membrane integrated carotenoids in some halophilic archaeal species, acting as photoprotection system against long lasting exposure to solar radiation. Moreover, they support the survival in hypersaline environment by controlling membrane fluidity to allow the permeability of oxygen and nutrients (Shahmohammadi et al. 1998).

In addition, bacterioruberin and its derivatives were found to be secreted in a temperature dependent manner in psychrotrophic species of Arthrobacter genus, for instance Arthrobacter agilis and Arthrobacter bussei, to enhance membrane plasticity at low temperature and protect it against freezing–thawing cycles (Fong et al. 2001b; Flegler and Lipski 2022b). Like bacterioruberin, other carotenoids have proven their role in cold adaptation, as example, Staphylococcus xylosus has showed a noticeable increase in staphyloxanthin production at 10 °C compared to 30 °C (Seel et al. 2020). Despite the fact that some Arthrobacter species synthesize bacterioruberin, the biosynthetic process in these microbes is still unknown (Flegler and Lipski 2022a).

Carotenoid glycosylation has been reported as a strategy to adapt to harsh conditions like extreme temperatures due to its role in enhancing membrane rigidity (Mohamed et al. 2005). Carotenogenic psychrotrophic species have been found to use carotenoid glycosylated derivatives to preserve the structural integrity of membranes under low temperature circumstances (Várkonyi et al. 2002). Glycosylation of carotenoids is carried out via glycosyltransferases (GTs), which is a broad enzyme family. Typically, the substituent moiety for glycosylation is a hydroxyl or carboxyl group of lipophilic substrates (Chen et al. 2021). The hydroxyl group is the most prevalent substituent moiety during carotenoid glycosylation. Bacterioruberin is glycosylated by glucosyltransferases of the GT-2 family that are unique to C50 carotenoids (Chen et al. 2021).

Glycosylation of carotenoids is not only beneficial for enhancing water solubility of carotenoids but also leads to structural diversity and many other benefits, such as enhanced bioavailability and efficacy as food and pharmaceutical supplements, improved photostability (Polyakov et al. 2009) and biological activities (e.g., antioxidant activity) (Matsushita et al. 2000). Recent studies have focused attention on generating glycosylated carotenoids via genetic engineering approaches to enhance their properties (Chen et al. 2021). In this respect, the capability of Arthrobacter sp. to produce glycosylated bacterioruberin is advantageous among bacterioruberin producing organisms.

In this study, C50 bacterioruberin carotenoid and its glycosylated derivatives were produced from the isolated strain NP20 of Arhrobacter agilis on cheese-whey-based medium as a highly nutritious, low-cost, and readily available substrate.

Cheese whey makes up 85–95% of the milk volume in dairy wastewaters, making it the most prevalent contaminant (Carvalho et al. 2013). It is considered a significant source of water pollution because of its high nitrogen content, which makes it 175 times more toxic than untreated human sewage (Smithers 2008). According to this perspective, microbial fermentation is the best method of treatment since it would lower the potential for contamination by lowering the nutritional content and turning the waste into value-added products (Zotta et al. 2020). In the introduced study, incorporating cheese-whey in the pigment production medium of the NP20 strain contributed to reducing the total nitrogen content to 75% of its value compared to the untreated whey sample.

To achieve maximum pigment yield, current studies have concentrated on understanding both nutritional and environmental factors to meet the necessary growth requirements of pigment-producing microorganisms. In this respect, statistical optimization experiments such as Response Surface Methodology (RSM) can be employed to optimize the nutritional and environmental conditions together that affect the production outcome (Cruz et al. 2020). In this study, three factors have been subjected to optimization via RSM to find the optimum response region for the maximal pigmentation in term of mg/L. The important contributing variables (MgSO4, whey % and inoculum %) were further investigated at three levels: − 1, 0 and + 1 to approach the pigment optimum response area with amount mg/L. The findings of surface plots revealed that raising the whey concentration and MgSO4 value while lowering the inoculum % (6%) resulted in higher levels of pigmentation.

Similar to the introduced study, whey-based medium was successfully used for carotenoid production from different species, for instance, β-carotene was produced from Blakeslea trispora using cheese whey-based medium (Roukas et al. 2015). The NP20 strain showed enhanced production of bacterioruberin with higher concentrations of MgSO4. The obtained results could be attributed to the biofunctionl role of Mg+ in promoting Crt genes expression to promote carotenoids biosynthesis. The obtained findings were in accordance with torpee et al., where higher MgSO4 concentrations improved carotenoid synthesis in Rhodopseudomonas palustris (Torpee et al. 2022). However, despite its important biofunction, the suitable concentrations of MgSO4 for maximum carotenoid production differ according to the genera, where higher concentration of MgSO4 was found inhibitory to pigment synthesis in Monascus sp. (Lin and Demain 1991).

It was found that the inoculum's size is a key element in carotenoid accumulation. Like NP20 strain, low inoculum size afforded higher carotenoid synthesis in Rhodococcus opacus PD630 compared to higher inoculum size (Thanapimmetha et al. 2017).

The R2 value for pigment production in this design was 0.8897, indicating a strong correlation between the actual and anticipated values. The experimentally verified optimal settings from the optimization experiment were compared to the model's anticipated optimum. The estimated pigment production was 6.01 mg/L, and the polynomial model predicted a value of 5.13 mg/L. This acceptable level of % error (~ 17%) indicates that the model was validated under ideal conditions. Furthermore, pigmentation in the improved medium was 2.2 times higher than in the baseline conditions (control). This demonstrated the importance and usage of the optimization process. The RSM is a commonly accepted advanced numerical method for optimizing experimental conditions and solving analysis problems in which a response is strongly impacted by many variables for the production of many industrially important biological molecules.

A cost benefit analysis was carried out to estimate the cost effectiveness of the optimized whey-based medium in comparison to Bacto marine broth medium, the previously reported medium for bacterioruberin production medium from Arthrobacter agilis (Fong et al. 2001a). The formulation of whey-based medium, the prices of the added ingredients as well as that of Bacto marine broth, calculated based on the lab scale cost, are shown in (Additional file 1: Table S1). Based on the analysis, the designed whey medium was 19.6-fold less expensive than Bacto marine broth, confirming the potentiality of whey-based medium as a cost-effective medium for bacterioruberin production from Arthrobacter agilis NP20. In addition, the whey-based medium has supported bacterioruberin synthesis with around fivefold enhancement compared to Bacto marine broth medium at the same incubation temperature, (5.1 mg/L compared to 1.1 mg/L).

The key performance parameters and operational variables of the introduced system have been compared to bacterioruberin production from different species of Haloarchaea (Abbes et al. 2013; Montero-Lobato et al. 2018; Vega et al. 2016) (Additional file 1: Table S2). Bacterioruberin production using whey-based medium via the NP20 strain of Arthrobacter agilis has demonstrated advantages in terms of cost effectiveness and eco friendliness compared to the previously reported systems. Moreover, the production yield was comparable to the compared species, which would favor the introduced system for future production of bacterioruberin carotenoids and their derivatives.

Currently, the preferred methodology for carotenoid analysis is HPLC with various detection techniques, such as DAD and MS (Breemen 1997). Since many carotenoids possess a highly similar UV–Vis spectra, it’s difficult to depend on the spectral characteristics alone as a final confirmation of carotenoids identity (Breemen 1997; Crupi et al. 2010). In this context, the information obtained by MS (molecular weight and characteristic fragmentation patterns) was very helpful since it made it possible to distinguish between carotenoid components with different molecular masses.

Several diseases are thought to be reduced by the antioxidant activity of carotenoids, and some of them, like lycopene and β-carotene, have well-known antioxidant qualities (Suleman et al. 2019). Carotenoids can be used as colorants or functional components in the food, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical industries thanks to their antioxidant action (Agarwal et al. 2023). The addition of carotenoids to foods may have significant positive effects on health, and their usage as antioxidants in the cosmetic industry is growing even more (Anunciato and Rocha Filho 2012). The high potentiality of bacterioruberin carotenoids in scavenging RSA is attributed to its long conjugated double bond system in comparison to other carotenoids. A concentration of 7 µg of NP20 carotenoids achieved (RSA%) of 54% while 50 µg of β-carotene achieved 12% only. The extract's enhanced effects can be attributed to the presence of several components that work in concert with one another. This outcome supports the benefit of employing natural blends rather than standalone antioxidants (Squillaci et al. 2017). Whole extracts rather than individual BR molecules are more closely related to the prospective applications of NP20 carotenoids.

Conclusion

Cheese whey-based medium has been proven as a potent nutritious substrate for producing bacterioruberin carotenoid and its unique glycosylated derivatives from Arthrobacter agilis NP20. The cost effectiveness of the newly developed medium creates a solid opportunity for bacterioruberin manufacturing on a wide scale. The low production cost of bacterioruberin carotenoid on whey-based media would facilitate the use of this rare carotenoid in a variety of sectors, including the food and cosmetics industries.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Abbes M, Baati H, Guermazi S, Messina C, Santulli A, Gharsallah N et al (2013) Biological properties of carotenoids extracted from Halobacterium halobium isolated from a Tunisian solar saltern. BMC Complement Altern Med 13(1):255

Agarwal H, Bajpai S, Mishra A, Kohli I, Varma A, Fouillaud M et al (2023) Bacterial pigments and their multifaceted roles in contemporary biotechnology and pharmacological applications. Microorganisms 11(3):614

Aman Mohammadi M, Ahangari H, Mousazadeh S, Hosseini SM, Dufossé L (2022) Microbial pigments as an alternative to synthetic dyes and food additives: a brief review of recent studies. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 45(1):1–12

Anunciato TP, da Rocha Filho PA (2012) Carotenoids and polyphenols in nutricosmetics, nutraceuticals, and cosmeceuticals. J Cosmet Dermatol 11(1):51–54

Arivizhivendhan KV, Mahesh M, Boopathy R, Swarnalatha S, Regina Mary R, Sekaran G (2018) Antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of bioactive prodigiosin produces from Serratia marcescens using agricultural waste as a substrate. J Food Sci Technol 55(7):2661–2670

Ashokkumar V, Flora G, Sevanan M, Sripriya R, Chen W, Park JH et al (2022) Technological advances in the production of carotenoids and their applications—a critical review. Bioresour Technol 367:128215

Carvalho F, Prazeres AR, Rivas J (2013) Cheese whey wastewater: characterization and treatment. Sci Total Environ 445:385–396

Celedón RS, Díaz LB (2021) Natural pigments of bacterial origin and their possible biomedical applications. Microorganisms. 9(4):739

Chen X, Lim X, Bouin A, Lautier T, Zhang C (2021) High-level de novo biosynthesis of glycosylated zeaxanthin and astaxanthin in Escherichia coli. Bioresour Bioprocess 8:1–13

Crupi P, Milella RA, Antonacci D (2010) Simultaneous HPLC-DAD-MS (ESI+) determination of structural and geometrical isomers of carotenoids in mature grapes. J Mass Spectrom 45(9):971–980

Cruz PP, Gutiérrez AM, Ramírez-Mendoza RA, Flores EM, Espinoza AAO, Silva DCB (2020) A practical approach to metaheuristics using LabVIEW and MATLAB®: Chapman and Hall/CRC.

Cumming G, Fidler F, Vaux DL (2007) Error bars in experimental biology. J Cell Biol 177(1):7–11

de la Vega M, Sayago A, Ariza J, Barneto AG, León R (2016) Characterization of a bacterioruberin-producing H. aloarchaea isolated from the marshlands of the O diel river in the southwest of S pain. Biotechnol Prog 32(3):592–600

Dummer AM, Bonsall JC, Cihla JB, Lawry SM, Johnson GC, Peck RF (2011) Bacterioopsin-mediated regulation of bacterioruberin biosynthesis in Halobacterium salinarum. J Bacteriol 193(20):5658–5667

Eden PA, Schmidt TM, Blakemore RP, Pace NR (1991) Phylogenetic analysis of Aquaspirillum magnetotacticum using polymerase chain reaction-amplified 16S rRNA-specific DNA. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 41(2):324–325

Flegler A, Lipski A (2021) The C50 carotenoid bacterioruberin regulates membrane fluidity in pink-pigmented Arthrobacter species. Arch Microbiol 204(1):70

Flegler A, Lipski A (2022a) Engineered CRISPR/Cas9 system for transcriptional gene silencing in arthrobacter species indicates bacterioruberin is indispensable for growth at low temperatures. Curr Microbiol 79(7):199

Flegler A, Lipski A (2022b) The C50 carotenoid bacterioruberin regulates membrane fluidity in pink-pigmented Arthrobacter species. Arch Microbiol 204(1):1–6

Flegler A, Runzheimer K, Kombeitz V, Mänz AT, Heidler von Heilborn D, Etzbach L et al (2020) Arthrobacter bussei sp. nov., a pink-coloured organism isolated from cheese made of cow’s milk. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 70(5):3027–3036

Fong N, Burgess M, Barrow K, Glenn D (2001a) Carotenoid accumulation in the psychrotrophic bacterium Arthrobacter agilis in response to thermal and salt stress. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 56:750–756

Fong N, Burgess M, Barrow K, Glenn D (2001b) Carotenoid accumulation in the psychrotrophic bacterium Arthrobacter agilis in response to thermal and salt stress. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 56(5):750–756

Galasso C, Corinaldesi C, Sansone C (2017) Carotenoids from marine organisms: biological functions and industrial applications. Antioxidants 6(4):96

Giani M, Garbayo I, Vílchez C, Martínez-Espinosa RM (2019) Haloarchaeal carotenoids: healthy novel compounds from extreme environments. Mar Drugs 17(9):524

Guleria S, Zhou J, Koffas MA (2017) Nutraceuticals (vitamin C, carotenoids, resveratrol). Industrial biotechnology: products and processes. pp 309–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/9783527807833.ch10

Gupta I, Adin SN, Panda BP, Mujeeb M (2022) β-Carotene—production methods, biosynthesis from Phaffia rhodozyma, factors affecting its production during fermentation, pharmacological properties: a review. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. https://doi.org/10.1002/bab.2301

Hou J, Cui H-L (2018) In vitro antioxidant, antihemolytic, and anticancer activity of the carotenoids from Halophilic archaea. Curr Microbiol 75:266–271

Jaswir I, Noviendri D, Hasrini RF, Octavianti F (2011) Carotenoids: sources, medicinal properties and their application in food and nutraceutical industry. J Med Plants Res 5(33):7119–7131

Jehlička J, Oren A (2013) Raman spectroscopy in halophile research. Front Microbiol 4:380

Jiménez-Escrig A, Jiménez-Jiménez I, Sánchez-Moreno C, Saura-Calixto F (2000) Evaluation of free radical scavenging of dietary carotenoids by the stable radical 2, 2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl. J Sci Food Agric 80(11):1686–1690

Jin Q, Yang L, Poe N, Huang H (2018) Integrated processing of plant-derived waste to produce value-added products based on the biorefinery concept. Trends Food Sci Technol 74:119–131

Liaaen-Jensen S, Jensen A (1971) [56] Quantitative determination of carotenoids in photosynthetic tissues. Methods in enzymology. p 586–602. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0076-6879(71)23132-3

Lin TF, Demain AL (1991) Effect of nutrition of Monascus sp. on formation of red pigments. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 36:70–75

Maia LF, De Oliveira VE, Edwards HGM, De Oliveira LFC (2021) The diversity of linear conjugated polyenes and colours in nature: Raman spectroscopy as a diagnostic tool. ChemPhysChem 22(3):231–249

Matsushita Y, Suzuki R, Nara E, Yokoyama A, Miyashita K (2000) Antioxidant activity of polar carotenoids including astaxanthin-β-glucoside from marine bacterium on PC liposomes. Fish Sci 66(5):980–985

Mohamed HE, van de Meene AM, Roberson RW, Vermaas WF (2005) Myxoxanthophyll is required for normal cell wall structure and thylakoid organization in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. J Bacteriol 187(20):6883–6892

Montero-Lobato Z, Ramos-Merchante A, Fuentes JL, Sayago A, Fernández-Recamales Á, Martínez-Espinosa RM et al (2018) Optimization of growth and carotenoid production by Haloferax mediterranei using response surface methodology. Mar Drugs 16(10):372

Mrowicka M, Mrowicki J, Kucharska E, Majsterek I (2022) Lutein and zeaxanthin and their roles in age-related macular degeneration—neurodegenerative disease. Nutrients 14(4):827

Mussagy CU, Winterburn J, Santos-Ebinuma VC, Pereira JFB (2019) Production and extraction of carotenoids produced by microorganisms. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 103(3):1095–1114

Nichols JA, Katiyar SK (2010) Skin photoprotection by natural polyphenols: anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and DNA repair mechanisms. Arch Dermatol Res 302(2):71–83

Polyakov NE, Leshina TV, Meteleva ES, Dushkin AV, Konovalova TA, Kispert LD (2009) Water soluble complexes of carotenoids with arabinogalactan. J Phys Chem B 113(1):275–282

Rodrigo-Baños M, Garbayo I, Vílchez C, Bonete MJ, Martínez-Espinosa RM (2015) Carotenoids from Haloarchaea and their potential in biotechnology. Mar Drugs 13(9):5508–5532

Roukas T, Varzakakou M, Kotzekidou P (2015) From cheese whey to carotenes by Blakeslea trispora in a bubble column reactor. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 175(1):182–193

Saito T, Miyabe Y, Ide H, Yamamoto O (1997) Hydroxyl radical scavenging ability of bacterioruberin. Radiat Phys Chem 50(3):267–269

Seel W, Baust D, Sons D, Albers M, Etzbach L, Fuss J et al (2020) Carotenoids are used as regulators for membrane fluidity by Staphylococcus xylosus. Sci Rep 10(1):1–12

Shahmohammadi HR, Asgarani E, Terato H, Saito T, Ohyama Y, Gekko K et al (1998) Protective roles of bacterioruberin and intracellular KCl in the resistance of Halobacterium salinarium against DNA-damaging agents. J Radiat Res 39(4):251–262

Silva TRe, Silva LCF, de Queiroz AC, Alexandre Moreira MS, de Carvalho Fraga CA, de Menezes GCA, et al. Pigments from Antarctic bacteria and their biotechnological applications. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2021;41(6):809–26.

Singh OV, Gabani P (2011) Extremophiles: radiation resistance microbial reserves and therapeutic implications. J Appl Microbiol 110(4):851–861

Smithers GW (2008) Whey and whey proteins—from ‘gutter-to-gold.’ Int Dairy J 18(7):695–704

Squillaci G, Parrella R, Carbone V, Minasi P, La Cara F, Morana A (2017) Carotenoids from the extreme halophilic archaeon Haloterrigena turkmenica: identification and antioxidant activity. Extremophiles 21(5):933–945

Suleman M, Khan A, Baqi A, Kakar MS, Ayub M (2019) 2. Antioxidants, its role in preventing free radicals and infectious diseases in human body. Pure Appl Biol 8(1):380–388

Sutthiwong N, Fouillaud M, Valla A, Caro Y, Dufossé L (2014) Bacteria belonging to the extremely versatile genus Arthrobacter as novel source of natural pigments with extended hue range. Food Res Int 65:156–162

Thanapimmetha A, Suwaleerat T, Saisriyoot M, Chisti Y, Srinophakun P (2017) Production of carotenoids and lipids by Rhodococcus opacus PD630 in batch and fed-batch culture. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 40:133–143

Torpee S, Kantachote D, Sukhoom A, Tantirungkij M (2022) Culture optimization to enhance carotenoid production of a selected purple nonsulfur bacterium and its activity against acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease-causing Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Biotechnol Appl Biochem 69(6):2422–2436

Usmani Z, Sharma M, Sudheer S, Gupta VK, Bhat R (2020) Engineered microbes for pigment production using waste biomass. Curr Genomics 21(2):80–95

Valduga E, Rausch Ribeiro AH, Cence K, Colet R, Tiggemann L, Zeni J et al (2014) Carotenoids production from a newly isolated Sporidiobolus pararoseus strain using agroindustrial substrates. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol 3(2):207–213

van Breemen RB (1997) Liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry of carotenoids. Pure Appl Chem 69(10):2061–2066

Várkonyi Z, Masamoto K, Debreczeny M, Zsiros O, Ughy B, Gombos Z et al (2002) Low-temperature-induced accumulation of xanthophylls and its structural consequences in the photosynthetic membranes of the cyanobacterium Cylindrospermopsis raciborskiian FTIR spectroscopic study. Proc Natl Acad Sci 99(4):2410–2415

Yang Y, Yatsunami R, Ando A, Miyoko N, Fukui T, Takaichi S et al (2015) Complete biosynthetic pathway of the C50 carotenoid bacterioruberin from lycopene in the extremely halophilic archaeon Haloarcula japonica. J Bacteriol 197(9):1614–1623

Yatsunami R, Ando A, Yang Y, Takaichi S, Kohno M, Matsumura Y et al (2014) Identification of carotenoids from the extremely halophilic archaeon Haloarcula japonica. Front Microbiol 5:100

Yusuf M, Shabbir M, Mohammad F (2017) Natural colorants: historical, processing and sustainable prospects. Nat Prod Bioprospect 7(1):123–145

Zotta T, Solieri L, Iacumin L, Picozzi C, Gullo M (2020) Valorization of cheese whey using microbial fermentations. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 104(7):2749–2764

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NN: Put the research concept, designing the experiments, carried out the experimental work, data analysis and manuscript writing. SNK: Data analysis and manuscript writing. NAS: Designing experiments, data analysis, and manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Cost analysis of Bacto marine broth and whey-based medium for bacterioruberin production. Table S2. Key performance parameters indicators and operational variables of bacterioruberin pigment production from different microorganisms. Figure S1. Actual by predicted plot for the measured response Y (Pigment conc. (mg/L)).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Noby, N., Khattab, S.N. & Soliman, N.A. Sustainable production of bacterioruberin carotenoid and its derivatives from Arthrobacter agilis NP20 on whey-based medium: optimization and product characterization. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 10, 46 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40643-023-00662-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40643-023-00662-3