Abstract

Background

The recovery characteristics of phase-forming polymers are essential for aqueous two-phase systems (ATPS) to recycle in bioseparation engineering.

Results

A new thermo-responsive copolymer (PVBAm) is suggested based on N-vinylcaprolactam, acrylamide, and butyl methacrylate. Together with another thermo-responsive polymer, poly (N-isopropyl acrylamide) (PN), it has been applied to form a recyclable ATPS. PVBAm and PN were designed to obtain structures and molecular weights allowing a lower critical solution temperature (LCST). By polymerization optimization, both PN and PVBAm were obtained with recoveries 98.5% and 95% above their LCST (i.e., PN 32.5 °C and PVBAm 40.5 °C), respectively, which allows each ATPS phase to be effectively recycled. The recycled ATPS based on PVBAm and PN was applied to the partitioning of vitamin B12. Under optimized conditions (5% PVBAm/3.5 %PN ATPS, in the presence of 0.8 M KCl, pH 4.0), the partition coefficient of vitamin B12 reached a value of 5.81.

Conclusion

The new ATPS based on the thermo-responsive copolymer PVBAm/PN possessed appropriate recycling characteristics regarding LCST, as well as recovery and phase separation characteristics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Aqueous two-phase systems (ATPS) are promising alternatives to extract and purify biomolecules thanks to high biocompatibility and readiness to scaling up (Molino et al. 2013). ATPS have been applied for bioseparation since several decades (Asenjo and Andrews 2012), but not yet applied to industrial processes. Conventional ATPS were traditionally prepared from polyethylene glycol and salts or dextran and applied for the extraction of different biomolecules (Ramesh and Murty 2015). These original phase-forming components were difficult to recover, due to high cost and the large amounts of salt required, which limited their use for process-scale separations. In recent years, recyclable ATPS have been suggested as alternatives to traditional ATPS, particularly based on thermo-responsive (TR) polymers.

During the past decades, polymers based on ethylene oxide-propylene oxide (EOPO) have been extensively studied in TR ATPS (Koon et al. 2015). Thus, in 1995, Berggren et al. (1995) reported the first preparation of ATPS based on an ethylene oxide–propylene oxide (EOPO) TR copolymer. In a subsequent study, Persson et al. (1999) used EO50PO50 to form ATPS with a hydrophobically modified random copolymer of EO and PO (HM-EOPO). The TR polymers used in these ATPSs could be recycled via a temperature-induced phase separation process. The recoveries of EO50PO50 and HM-EOPO were 73% and 97.5%, respectively. In a study by Ng et al. (2012) in 2012, EOPO3900 (LCST 50 °C) was used to form ATPS with potassium phosphate, achieving a recovery of 83.1%.

Other kinds of TR polymers can be recycled by temperature-induced precipitation, such as polymers based on N-isopropylacrylamide (NIPA) and N-vinylcaprolactam, (NVCL). NIPA has been the most widely used monomer for the synthesis of TR polymers (Sulu et al. 2017); because of their good responsive characteristics and favorable LCST (32 °C), NIPA polymers have been studied and used in both laboratory and industrial scale. They have also been reported to form ATPS as affinity polymers (Tan et al. 2017). The use of polymers based on NVCL was reported by Shostakovski (1959) already in 1957. However, despite its long history, the first PNVCL-based application was not published until in 1996 (Makhaeva et al. 1996). In 2008, the behavior of PNVCL in ATPSs was reported for the first time by Foroutan et al. (2008). The LCST of PNIPA and PNVCL (32–34 °C) is near to the physiological temperature range. However, there are still few reports that polymers based on NIPA and NVCL have been applied in bioseparations.

In our laboratory, we have recently developed new ATPS forming polymers based on N-isopropyl acrylamide (NIPA) or N-vinylcaprolactam (NVCL) as monomers. A thermo-pH-responsive ATPS has been reported, which constitutes a TR polymer poly (N-isopropyl acrylamide-co–n-butyl acrylate) (PNB) and a pH-responsive terpolymer (Miao et al. 2010). Hou reported ATPS formed by thermo-responsive copolymers PNE (N-isopropyl acrylamide/ethyl methacrylate) and PVAm (NVCL-acrylamide) (Hou and Cao 2014).

To obtain ATPS suitable for industrial scale separation, new recyclable ATPS comprising two TR polymers, PVBAm (NVCL-butyl methacrylate-acrylamide) and PN (NIPA) with higher LCST, were tried in this study and applied to the partition of vitamin B12 (VB12). The purification of VB12 is traditionally based on organic solvent extraction and, therefore, in order to answer a demand for environmental friendly purification processes is a suitable model for ATPS. Furthermore, the newly designed PVBAm/PN ATPS was compared with other reported TR ATPS regarding the polymerization process, the polymer LCST, the recovery, the phase formation and the recycling characteristics.

Methods

Materials

N-isopropyl acrylamide (NIPA) and VB12 (98%) were purchased from Jing Chun Chemical Co. (Shanghai, China). NVCL was purchased from Ao Te Chemical Co. (Zibo, China), and acrylamide (Am), butyl methacrylate (BMA), 2-2′-azoisobutyronitrile (AIBN), benzene, hexane, petroleum ether, acetone, tetrahydrofuran (THF), and ethanol were obtained from Ling Feng Chemical Co. (Shanghai, China). All chemicals were of analytical grade and used without further purification.

Polymerization of P VBAm and P N

PVBAm was polymerized as illustrated in Fig. 1a. Different ratios of NVCL, BMA and Am were used as monomers dissolved in 150 mL benzene, with different concentrations of AIBN (0.5–5.5%, w/w) as initiator. The solutions were stirred using a magnetic stirrer under a constant flow of nitrogen for 15 min before polymerization. The polymerization reaction was carried out at different temperatures (50–70 °C) for 24 h in a water bath shaker at a speed of 120 rpm. In order to remove residual benzene and impurities, such as unreacted AIBN, the products were dissolved in 100 mL THF and precipitated by the addition of hexane. Finally, the precipitate was washed with ethanol and dried under vacuum to constant weight.

PN was synthesized as illustrated in Fig. 1b. First, 5.0 g N-isopropyl acrylamide was dissolved in 150 mL benzene in the presence of different concentrations of AIBN (0.5–5.5%, w/w). After 15-min nitrogen de-oxygenation, the polymerization reaction applied was identical to that of PVBAm. The products obtained were dissolved in 100 mL acetone, precipitated by the addition of hexane, and dried under vacuum at 55 °C to constant weight.

Characterization of P VBAm and P N

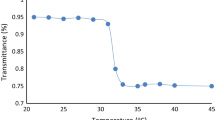

The PVBAm and PN reaction products were analyzed using a Nicolet 6700 FTIR spectrometer (Thermo Electron Corporation, UK). The molecular weights of the copolymers were determined using an Ubbelohde viscometer and calculated according to the Kuhn–Mark–Houwink equation (Scholte et al. 1984). The LCST of the copolymers was determined by measuring the transmittance of 5% PVBAm and 5% PN at different temperatures, using a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Japan).

Recycling of P VBAm and P N

The recoveries of PVBAm and PN were determined by measuring the amount obtained after thermo-precipitation above LCST. Thus, the precipitate was filtered and dried to constant weight. To this end, solutions of PVBAm and PN in the pH range 4.0–10.0 were prepared and thermo-precipitated. The effect of different concentrations of salt (KCl, NaCl, Na2SO4, K2SO4, Na2HPO4, and NaH2PO4) on polymer recovery was further investigated on a 10% solution of PVBAm and PN.

Construction of phase diagram

The Cloud Point Method (Pfenning et al. 1998) was used to construct a PN/PVBAm ATPS phase diagram. Thus, a binodal curve was drawn on the basis of the change in turbidity when two phases were formed. To this end, a 10% solution of PN was added dropwise to a 10% solution of PVBAm and mixed in test tubes using a vortex mixer. The concentrations of PN and PVBAm at each turbidity point were calculated according to the additional mass and volume in the system. Finally, the binodal curve was drawn based on the concentrations of PN and PVBAm. The tie line of the M point was obtained as follows: PN and PVBAm were mixed for several minutes and settled at room temperature until a clear phase was obtained, followed by determination of the phase volume ratio The concentrations of PN and PVBAm in the top and bottom phases were measured by UV spectrophotometry (Shimadzu, Japan). The concentration of PN was measured at 190 nm with reference to a standard curve. The concentration of PVBAm was calculated by subtracting the absorbance of PN from the total absorbance of PN and PVBAm at 210 nm. Finally, a tie line was drawn based on the concentrations of PN and PVBAm in the top and bottom phases, respectively.

Partition of vitamin B12

The PVBAm/PN ATPS was applied to the partitioning of vitamin B12. The initial concentration of VB12 in the ATPS was 0.2 mg/mL. The effects of pH and inorganic salts on the partition of VB12 were investigated. After the ATPS reached equilibrium at room temperature, aliquots were sampled from the top and bottom phases using a micro-syringe. The concentration of VB12 in both phases was determined by measuring the absorbance of the samples using a UV–vis spectrophotometer at 361 nm (Jin and Guo 2007). The partition coefficient of VB12 was calculated as the ratio of the concentrations in the top and bottom phases, respectively. The recovery yield (YR) was calculated according to the following equation:

where K is the partition coefficient, Vb is the volume of the bottom phase and Vt is the volume of top phase.

Each experimental condition was subject to three parallel repetitions and all measurements were repeated at least three times until reproducible data were obtained. The data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and analyzed by Excel.

Results and discussion

Characterization of P VBAm and P N

In this study, the TR copolymer PVBAm is designed and synthesized using three functional monomers. Among them, NVCL forms the main backbone of PVBAm and is responsible for the thermo-responsive function; BMA contains a hydrophobic group that is used to adjust the solubility and the LCST. Finally, Am contributes to the hydrophilic properties of the copolymer. The TR copolymer PN is polymerized using only one monomer, i.e., NIPA.

Viscosity average molecular weight

During polymerization, the viscosity average molecular weight (Mv) of the polymer is strongly influenced by the reaction temperature and the amount of the initiator AIBN. Thus, the Mv of PVBAm and PN decreases at higher reaction temperatures (Fig. 2a). And higher AIBN concentrations leads to higher Mv in the low concentration range and then its Mv decreased with an increase in AIBN concentration (Fig. 2b). The polymer molecular weight strongly influences the phase formation: thus phases are not formed by polymers with too low Mv. In contrast, ATPS formed by polymers with high Mv result in a very viscous solution that is detrimental to effective mass transfer. With respect to phase formation and viscosity, 1.5% and 4.0% (w/w) AIBN are preferably used for polymerization of PN and PVBAm, respectively, and with a reaction temperature of 65 °C. For optimum performance a Mv of PN and PVBAm, respectively, are 5.41 × 104 and 8.91 × 104 Da and with an NVCL/BMA/Am monomer ratio: 5:0.5:0.2 with polymerization yields of 96.8% and 92.8% for PN and PVBAm, respectively.

Effect of a temperature and b concentration of AIBN on Mv of PVBAm and PN; The polymerization reaction was carried out for 24 h at a shaking speed of 120 rpm. PVBAm was polymerized with an NVCL/BMA/Am monomer ratio: 5:0.5:0.2. Mv was measured at 25 °C. In a 4% (w/w) AIBN was used as the initiator; in b the reaction was carried out at 65 °C

Structure of P VBAm

The synthesized PVBAm was characterized by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and the results are shown in Fig. 3. The spectrum features a minor peaks at 3330 cm−1, corresponding to free amino groups, and a band at 3200 cm−1 is identified as the characteristic band of primary amines (–NH2). These findings indicate that Am is present in PVBAm. The peaks at 1196 cm−1 and 1010 cm−1, respectively, are attributed to the C–O–C stretching of aliphatic ester groups, which indicate the presence of BMA in the chain of PVBAm. The peak at 720 cm−1 is assigned to the –CH2 rocking of long chain –(CH2)4–, which indicates the presence of NVCL in the prepared PVBAm. The peaks at 2925 cm−1 and 2854 cm−1, respectively, are attributed to the C–H symmetric and asymmetric stretching of methylene groups, the peak at 1648 cm−1 is assigned to the C=O stretching vibration and the peak at 1440 cm−1 is assigned to the C–H bending vibration. The above three kinds of absorption maxima are present in all Am, BMA and VCL polymers. Based on the FTIR analysis, it can concluded that all three monomers are successfully polymerized.

Lower critical solution temperature

The lower critical solution temperature (LCST) of the two TR polymers was studied to explore their thermo-induced precipitation temperature. Solutions of PVBAm and PN are transparent at temperatures below their LCST and become turbid above their LCST. As shown in Fig. 4a, the temperature increase from 26 to 34 °C for PN indicates an LCST of PN at 32.5 °C. To obtain a PVBAm preparation with higher LCST, polymerization with different monomer ratios was studied (Table 1; Fig. 4b). Thus, the LCST of PVBAm with an NVCL/BMA/Am monomer ratio of 5:0.5:0.1 is 37.8 °C. Increasing the content of Am led to increased energy requirements to destroy the hydrogen bonds between the amide groups and the water molecules. Consequently, the LCST of PVBAm with an NVCL/BMA/Am ratio of 5:0.5:0.2 increased from 37.8 to 40.5 °C. In contrast, decreasing the content of BMA in PVBAm led to a minor increase of LCST from 40.5 to 41.0 °C. However, the low ratio of BMA resulted in lower molecular weight and low recovery of PVBAm (Table 1). PVBAm with an NVCL/BMA/Am ratio of 5:0.5:0.1 cannot form a two-phase system with PN regardless of the concentration. So, based on the results of LCST, recovery, and ATPS formation, an NVCL/BMA/Am monomer ratio of 5:0.5:0.2 is selected with an LCST of 40.5 °C, which is appropriate for its application in a high temperature environment. According to the above results, it is possible to conclude that when the temperature is below the LCST of both PVBAm and PN, they can form ATPS, and when the temperature exceeds their LCST, PVBAm and PN will be precipitated from either top or bottom phase.

Recovery of P VBAm and P N

Favorable recovery characteristics of the phase-forming polymers are essential for proper recycling of aqueous two-phase systems (ATPS). In this study, the recovery of the TR polymers was explored by changing the solution temperature. When the solution was heated above their LCST, PVBAm and PN became insoluble forming clots. When the temperature was reset below their LCST, the clots were re-dissolved. The conclusion is that PVBAm and PN are thermo-responsive and can be recycled by temperature change. It is also concluded that adjustment of pH and the addition of inorganic salts can improve the recovery of PVBAm and PN.

As shown in Fig. 5, with an initial pH value of the polymer solution around 5.0–6.0, the recovery of PN was not obviously influenced by pH change reaching > 95% in the pH range 4.0–10.0, and 98.0% at pH 10. However, in contrast, the recovery of PVBAm shows an obvious increase at higher pH values,reaching a maximum recovery of 92.3% at pH 10.0. For the TR copolymer, an increase in temperature is the main factor for inducing PVBAm aggregation by breaking hydrogen bonds between PVBAm and water molecules. Besides temperature, the solution pH also influences the strength of the hydrogen bonds. In general, the greater the polarity of the molecule, the greater the effect is of the hydrogen bond on its solubility. Although PVBAm does not contain ionic groups, it contains a terminal amide bond, so its solubility is more influenced by hydrogen bonding than PN which has got an internal amide bond. The result is a larger effect of pH on the recovery of PVBAm. Under acidic conditions, there are enough hydrogen ions in the solution, so PVBAm cannot easily precipitate, because of the strong hydrogen bonding between the water molecules and PVBAm. With the increase of pH, the hydrogen bonds are weakened and the inter-molecular hydrogen bonds of PVBAm become strong, making PVBAm precipitate more easily.

The presence of inorganic salts also influences the polymer recovery. As shown in Fig. 6, the recoveries of both PVBAm and PN are improved by the addition of salts, except for Na2SO4 and K2SO4, and they are slightly higher in 50 mM than in 20 mM. The recoveries of PVBAm and PN in the presence of 50 mM KCl increased to 98.5% and 94.7%, respectively. However, the effect of inorganic salts on recovery is not obvious for PN, probably owing to the absence of ionizable groups.

In conclusion, through optimization, both PVBAm and PN can be recovered effectively by precipitation, and the ATPS formed by PVBAm and PN can be easily recycled. The scheme of PVBAm/PN ATPS formation and recycling is shown in Fig. 7.

Phase diagram of P VBAm/P N ATPS

Phase diagrams of ATPS indicate their biphasic composition, the concentration of phase components in the top and bottom phases, and the ratio of phase volumes, and they are very useful for guiding phase formation and molecular partitioning. The phase diagram of the PVBAm/PN ATPS is shown in Fig. 8. The area above the binodal curve represents the two-phase region. Within a pH range of 4.0–6.0 (initial pH of the ATPS is 5.12), a clear phase layer is observed. As shown in the diagram, very low concentrations of both PVBAm and PN are required to form ATPS, which means a lower application cost. For example, in the diagram M represents the composition of the polymers in the ATPS (5.0% PVBAm and 3.5% PN), which was used for partitioning in the following experiment. Furthermore, T and B on the binodal curve represent the concentrations of PVBAm and PN in each phase, 7.5% PVBAm and 1.1% PN in the top phase and 0.9% PVBAm and 7.2% P N in the bottom phases, indicating that PN or PVBAm are mainly enriched in one phase, which is very beneficial for the recycling of the phase-forming polymer. The ratio of the phases is calculated according to the length ratio of the lines MB and MT on the tie line TMB, giving a ratio of the M system to be 2:1.

Partition of vitamin B12 in P VBAm/P N ATPS

For the development of a low cost and environmental friendly separation method, in order to avoid organic solvent extraction, the recyclable PVBAm/PN ATPS has been applied to the partitioning of vitamin B12 including the influence of pH and inorganic salts.

Taking the stability of VB12 and the phase formation range of ATPS into consideration, pH is kept in the range 4.0–6.0. In this range, vitamin B12 tends to partition to the top phase enriched in PVBAm. The partition coefficient decreases slightly from 2.48 to 1.74 with an increase of pH from 4.0 to 6.0 (Fig. 9a). The decreasing K trend can be attributed to charge effects. VB12 contains a phosphate anion and six terminal amide bonds, and PVBAm also contains a terminal amide bond. The above groups show slightly more negative charge at increasing pH values. Therefore, VB12 moved to the bottom phase, owing to electrostatic repulsion, resulting in a slight decrease of the partition coefficient.

Inorganic salts are frequently used in ATPSs to improve the partition coefficient (K). Different cations and anions (NaCl, Na2SO4, KCl, K2SO4, and NH4Cl) were explored in the range 10–100 mM (Table 2). The effect of NaCl and KCl on K displayed an upward trend, whereas reduced K values were obtained for other salts with increasing concentrations. The highest K (2.62) was observed in 100 mM KCl. Therefore, the effect of higher KCl concentrations (0.1–1.0 M) on partition behavior was further investigated, as shown in Fig. 9b. The K value increased gradually with an increase of KCl concentration, reaching 5.81 in 0.8 M KCl, whereas two phases could not be formed at higher concentrations (0.9 and 1.0 M). Inorganic ions can generate an electrostatic potential difference over the interface and the Donnan effect requires electrostatic neutrality between the two phases (Iqbal et al. 2016; Hou et al. 2014). Thus, an uneven concentration of inorganic salts in the two phases influenced the partition of VB12. High salt concentration also causes salting-out which may also influence the partition. In addition, other forces, such as hydrogen bonds, may also influence the partition behavior of VB12 in such a complex system (Wang et al. 2008). The recovery yield of VB12 was 92.1% when K was 5.81 and Vb/Vt was 0.5.

Recovery comparison of P VBAm/P N ATPS with other TR ATPS

NIPA and VCL are widely employed as thermo-sensitive polymers for smart fibers, surfaces and hydrogels (Kim and Matsunaga 2017). However, there are very few reports regarding their application in ATPS (Tan et al. 2017). In our laboratory, six different TR polymers have been synthesized and applied in ATPS (as shown in Table 3). Among those polymers, N-Isopropyl acrylamide (NIPA) or N-vinylcaprolactam (VCL) was used as the thermo-responsive monomer. Factors such as monomer component, LCST, recovery and molecular weight are important for TR polymers to form ATPS. To this end, PVBAm and PN were compared with other published TR polymers regarding the above factors.

Influence of polymerization medium

Either organic solvents or water can be used as medium for TR polymer polymerization. Although water is environmental friendly, we have found that the polymerization yields and recoveries in water are not as high as in organic solvents. In this study, PVBAm and PN are polymerized in benzene, giving higher yields than in water (Table 3). Moreover, when polymerized in benzene, PVBAm and PN shrunk to a clot when heated above their LCST and could easily be removed, whereas when polymerized in water, they needed to be centrifuged before recovery. In another TR ATPS (Table 3), PNBAa polymerized in benzene also showed high yields after forming clots that can be easily collected, whereas PNE polymerized in water only gave 85.8% yield and needed to be centrifuged to be collected.

Influence of Mw on TR polymers

The polymer molecular weight (Mw) relates to both solution viscosity and solubility. We have found that PNE with Mw 1.89*106 will need several hours to dissolve from a dry solid and its solution is very viscous, thus it is not suitable for ATPS formation. The Mw of other polymers tested, as shown in Table 3, showed a span of four orders of magnitude, but did not show obvious differences in viscosity and solubility. It has been reported that polymers with low Mw show higher LCST and form ATPS at higher concentrations (Iqbal et al. 2016).

Influence of LCST on the recovery of TR polymers

The most important characteristic of TR polymers is their low critical solution temperature (LCST). When the temperature is above LCST, the polymers become insoluble and precipitate. Although a low LCST can reduce the risk of denaturation of biomolecules during temperature-induced precipitation, LCST values below 30 °C, such as for PNBAa and PNE (Table 3), may cause the polymer to precipitate at high room temperatures. For example, a hot summer day would affect the formation of ATPS. Therefore, because PNBAa/PNDB and PNE/PVAm ATPS contain a polymer with low LCST, they are unsuitable to be applied to partition at high ambient temperatures, as shown in Tables 3 and 4. The LCST of PVBAm in this study was 40 °C. Such LCST is suitable for the formation of ATPS at higher temperatures, preserving the activity of biomolecules during temperature-induced polymer precipitation. The LCST value of the widely applied TR copolymer EO50PO50 is about 50 °C and temperature-induced phase separation may occur at about 65 °C (see Table 3), which is higher than safe temperatures for many biomolecules. Therefore, TR polymers with LCST in the range of 30–40 °C are more suitable to form ATPS for biomolecule separation.

Recovery state of TR polymers

All TR polymers reported in Table 3 achieved more than 95% recovery with optimized salts in the solution. However, the degree of recovery differs significantly between polymers composed of NIPA or VCL and polymers based on the EOPO series. When the solution temperature increases to above LCST, polymers composed of NIPA or VCL become insoluble and precipitate. When ATPS are formed based on such polymers, for example the PVBAm/PN in this study, and after partition and phase separation has occurred, each phase containing NIPA or VCL is heated to above its LCST, so that the phase forming polymer precipitates and is separated from the biomolecules, after which the polymer can be dissolved and recycled to form ATPS again. On the other hand, when ATPS are formed using polymers based on the EOPO series, after partition and phase separation, the phase containing the EOPO copolymer (5–20%) when heated above its LCST does not precipitate, but remain in solution, with the top phase containing almost all water-soluble biomolecules, whereas the bottom phase contains about 40–60% EOPO polymer. This means that polymers based on NIPA or VCL, such as PN, PVBAm, PNBAa, PNDB, PNE, show temperature-induced precipitation, and polymers based on EOPO, such as EO50PO50, HM-EOPO, L44, L31, do not show temperature-induced phase separation (Table 4).

ATPS formed by different polymer types

The ATPS (PVBAm/PN, PNBAa/PNDB, and PNE/PVAm) in Table 4 are composed of two TR polymers and, after phase separation, each polymer is enriched in one phase and can be recovered by temperature-induced precipitation. However, for other ATPS based on one TR polymer and a none-TR component, such as dextran, starch, and salt, only one phase can be subject to temperature-induced recovery and the other phase is still difficult to recover. It has also been reported that ATPS with two TR polymers (EOPO and HM-EOPO) both can be recovered by temperature-induced precipitation. However, the LCST of HM-EOPO was only 14 °C (Table 4).

In addition, different types of ATPS require different polymer concentration to form ATPS. As shown in Table 4, when both phase-forming polymers are TR polymers, such as PVBAm/PN ATPS, a lower concentration of the TR polymer (≤ 5%) is needed for ATPS formation. On the other hand, a higher polymer concentration is often needed for the ATPS formed with one TR polymer and another component such as dextran or salt.

Conclusions

A new TR polymer PVBAm with suitable LCST is synthesized and can be recycled with high recovery, and a new recyclable ATPS is designed using a combination of PVBAm and the TR polymer PN. Compared to previous TR polymers tested in our laboratory, the LCST of the two polymers in this study is more favorable (32.5 °C and 40.5 °C) and is higher than the previously tested polymers (28.7 °C and 35.6 °C). Therefore, they have the ability to form ATPS easier than previous polymers at high room temperatures. Furthermore, the properties of the two polymers in this study differ to such an extent that they can be easily separated from the system. A VB12 partition coefficient of 5.81 was obtained using the 5.0% PVBAm/3.5 % PN ATPS. Thus, the PVBAm/PN ATPS has got appropriate recycling characteristics regarding LCST, recovery and phase separation. These data are valuable for the promotion of ATPS to be applied in industrial bioseparation processes.

Abbreviations

- NIPA:

-

N-isopropylacrylamide

- NVCL:

-

N-vinylcaprolactam

- P VBAm :

-

Poly (NVCL-butyl methacrylate-acrylamide)

- P N :

-

Poly (N-isopropylacrylamide)

- VB12:

-

vitamin B12

- ATPS:

-

Aqueous two-phase systems

- TR polymer:

-

thermo-responsive polymer

- Mv:

-

viscosity average molecular weight

- LCST:

-

lower critical solution temperature

References

Asenjo JA, Andrews BA (2012) Aqueous two-phase systems for protein separation: phase separation and applications. J Chromatogr A 18:1–10

Berggren K, Johansson HO, Tjerneld F (1995) Effects of salts and the surface hydrophobicity of proteins on partitioning in aqueous two-phase systems containing thermoseparating ethylene oxide-propylene oxide copolymers. J Chromatogr A 718:67–69

Foroutan M, Zarrabi M (2008) Quaternary (liquid + liquid) equilibria of aqueous two-phase polyethelene glycol, poly-N-vinylcaprolactam, and KH2PO4: experimental and the generalized Flory–Huggins theory. J Chem Thermodyn 40:935–941

Hou DS, Cao XJ (2014) Synthesis of two thermos-responsive copolymers forming recyclable aqueous two-phase systems and its application in cefprozil partition. J Chromatogr A 1349:30–36

Hou DS, Li YJ, Cao XJ (2014) Synthesis of two thermo-sensitive copolymers forming aqueous two-phase systems. Sep Sci Technol 122:217–224

Iqbal M, Tao YF, Xie SY (2016) Aqueous two-phase system (ATPS): an overview and advances in its applications. Biol Proced 18:18–26

Jin YQ, Guo LM (2007) The Content Measurement of V-B12 by UV-Vis. J Changzhi Med Coll 21:251–254

Kim YJ, Matsunaga YT (2017) Thermo-responsive polymers and their application as smart biomaterials. J Mater Chem B 5:4307–4320

Koon YY, Ooi CW, Ng EP, Lan JCW, Ling TC, Show PL (2015) Current applications of different type of aqueous two-phase systems. Bioresour Bioprocess 2:49–62

Makhaeva EE, Thanh LTM, Starodoubtsev SG, Khohlov AR (1996) Thermoshrinking behavior of poly(vinylcaprolactam) gels in aqueous solution. Macromol Chem Phys 197:197–1982

Miao S, Chen JP, Cao XJ (2010) Preparation of a novel thermo-sensitive copolymer forming recyclable aqueous two-phase systems and its application in bioconversion of penicillin G. Sep Purif Technol 75:156–164

Molino JVD, Marques DAV, Júnior AP, Mazzola PG, Gatti MSV (2013) Different types of aqueous two-phase systems for biomolecule and bioparticle extraction and purification. Biotechnol Prog 29:1343–1353

Moreiraa S, Silvériob SC, Macedoc EA, Milagresa AMF, Teixeirab JA, Mussattob SI (2013) Recovery of peniophora cinerea laccase using aqueous two-phase systems composed by ethylene oxide/propylene oxide copolymerand potassium phosphate salts. J Chromatogr A 1321:14–20

Ng HS, Tan CP, Mokhtar MN, Ibrahim S, Ariff A (2012) Recovery of bacillus cereus cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase and recycling of phase components in an aqueous two-phase system using thermo-separating polymer. Sep Purif Technol 89:9–15

Persson J, Johansson HO, Tjerneld F (1999) Purification of protein and recycling of polymers in a new aqueous two-phase system using two thermoseparating polymers. J Chromatogr A 864:31–48

Persson J, Kaul A, Tjerneld F (2000) Polymer recycling in aqueous two-phase extractions using thermoseparating ethylene oxide–propylene oxide copolymers. J Chromatogr B 743:115–126

Pfenning A, Schwerin A, Gaube J (1998) Consistent view of electrolytes in aqueous two-phase system. J Chromatogr B 711:45–52

Pietruszka N, Galaev IY, Kumar A, Brzozowski ZK, Mattiasson B (2000) New polymers forming aqueous two-phase polymer systems. Biotechnol Prog 16:408–415

Ramesh V, Murty VR (2015) Partitioning of thermostable glucoamylase in poly-ethyleneglycol/salt aqueous twophase system. Bioresour Bioprocess 2:25–43

Scholte TG, Meijerink NLJ, Schoffeleers HM, Brands AMG (1984) Mark-Houwink equation and GPC calibration for linear short-chain branched polyolefines, including polypropylene and ethylene copolymers. J Appl Polym Sci 29:3763–3782

Shostakovskii MF, Sidelkovskaya FP (1959) Investigation of lactones and lactams communication 14. Synthesis of n-vinylcaprolactam by the indirect-vinylation method. Russ Chem Bull 8:859–862

Sulu E, Biswas CS, Stadler FJ, Hazer B (2017) Synthesis, characterization, and drug release properties of macroporous dual stimuli responsive stereo regular nanocomposites Gels of Poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) and graphene oxide. J Porous Mater 24:389–401

Tan ZJ, Li FF, Zhao CC, Teng YB, Liu YF (2017) Chiral separation of mandelic acid enantiomers using an aqueous two-phase system based on a thermo-sensitive polymer and dextran. Sep Sci Technol 172:382–387

Wang W, Wan JF, Ning B, Xia JA, Cao XJ (2008) Preparation of a novel-sensitive copolymer and its application in recycling aqueous two-phase system. J Chromatogr A 1205:171–176

Wang Y, Hu X, Han J, Ni L, Tang X, Hu YG, Chen T (2015) Integrated method of thermosensitive triblock copolymer–salt aqueous two phase extraction and dialysis membrane separation for purification of lycium barbarum polysaccharide. Food Chem 194:257–264

Xu CN, Dong WY, Wan JF, Cao XJ (2016) Synthesis of thermo-responsive polymers recycling aqueous two-phase systems and phase formation mechanism with partition of polylysine. J Chromatogr A 1472:44–54

Authors’ contributions

JW conceived, designed, and wrote the paper, WD performed parts of the experiments, DH performed a part of polymerization, ZW performed a part of partition experiments, XC was involved in project planning, experimental designing, manuscript revisions, and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Prof. Jan-Christer Janson (Uppsala University) for English language editing.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All data obtained or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Consent for publication

All of authors have read and approved to submit it to bioresources and bioprocessing.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21376078) and National Special Fund for State Key of Bioreactor Engineering (2060204).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wan, J., Dong, W., Hou, D. et al. Polymerization of a new thermo-responsive copolymer with N-vinylcaprolactam and its application in recyclable aqueous two-phase systems with another thermo-responsive polymer. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 5, 44 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40643-018-0231-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40643-018-0231-7