Abstract

We present a comparative study of high-intensity long-duration continuous AE activity (HILDCAA) events, both isolated and those occurring in the “recovery phase” of geomagnetic storms induced by corotating interaction regions (CIRs). The aim of this study is to determine the difference, if any, in relativistic electron acceleration and magnetospheric energy deposition. All HILDCAA events in solar cycle 23 (from 1995 through 2008) are used in this study. Isolated HILDCAA events are characterized by enhanced fluxes of relativistic electrons compared to the pre-event flux levels. CIR magnetic storms followed by HILDCAA events show almost the same relativistic electron signatures. Cluster 1 spacecraft showed the presence of intense whistler-mode chorus waves in the outer magnetosphere during all HILDCAA intervals (when Cluster data were available). The storm-related HILDCAA events are characterized by slightly lower solar wind input energy and larger magnetospheric/ionospheric dissipation energy compared with the isolated events. A quantitative assessment shows that the mean ring current dissipation is ~34 % higher for the storm-related events relative to the isolated events, whereas Joule heating and auroral precipitation display no (statistically) distinguishable differences. On the average, the isolated events are found to be comparatively weaker and shorter than the storm-related events, although the geomagnetic characteristics of both classes of events bear no statistically significant difference. It is concluded that the CIR storms preceding the HILDCAAs have little to do with the acceleration of relativistic electrons. Our hypothesis is that ~10–100-keV electrons are sporadically injected into the magnetosphere during HILDCAA events, the anisotropic electrons continuously generate electromagnetic chorus plasma waves, and the chorus then continuously accelerates the high-energy portion of this electron spectrum to MeV energies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Relativistic (MeV) electrons in the Earth’s outer radiation belt (L > 3.5) can at times have orders of magnitude variations on time scales of few minutes to several days. Earlier studies have indicated that the largest flux variations occur during geomagnetic storms (Baker et al. 1994; Li et al. 1997). Typically, relativistic electron fluxes decrease during the geomagnetic storm main phase and recover during the storm recovery phase (Baker et al. 1994; Onsager et al. 2002; Horne et al. 2009). Intense relativistic electron flux variations have also been noted during high-speed solar wind streams (HSSs) (Paulikas and Blake 1979).

The HSSs interacting with upstream slower-speed streams form high magnetic field regions called corotating interaction regions or CIRs (Smith and Wolfe 1976; Pizzo 1985; Balogh et al. 1999). CIRs interacting with the Earth’s magnetosphere can also cause magnetic storms, albeit somewhat weak storms, with typical intensities Dst >−100 nT (Tsurutani et al. 1995; Tsurutani and Gonzalez 1997; Alves et al. 2006). High-intensity long-duration continuous AE activity (HILDCAA: Tsurutani and Gonzalez 1987; Hajra et al. 2013) events created by some HSSs following the CIRs have been shown to lead to the acceleration of relativistic electrons within the Earth’s outer radiation belt (Tsurutani et al. 2006; Kasahara et al. 2009; Hajra et al. 2014a, 2015).

It is the purpose of this study to determine the possible effects of geomagnetic storms preceding HSS HILDCAA events on the acceleration of relativistic electrons. To do this, we will compare relativistic electron acceleration occurring during isolated HILDCAA events which occur in the absence of any significant storm signatures to those occurring after geomagnetic storm main phases. The geomagnetic characteristics and magnetospheric energy budget of the two classes of the events will also be compared.

Methods

HILDCAA events are distinguished by four strictly defined criteria (Tsurutani and Gonzalez 1987). These are intense auroral activity intervals characterized by peak AE intensity greater than 1000 nT, and a minimum of 2 days duration where AE does not drop below 200 nT for more than 2 h at a time. HILDCAAs, by definition, occur outside the main phases of geomagnetic storms. We use the above definitions of a HILDCAA in the present study. A geomagnetic storm is detected as a decrease in Dst with peak Dst ≤−50 nT (Akasofu 1981; Gonzalez et al. 1994), a definition used in this study.

Hajra et al. (2013) identified 133 HILDCAA events occurring during a ~3.5 solar cycle interval, from 1975 through 2011 using high-resolution AE (1 min) and Dst (1 h) data. The 43 HILDCAA events occurring during 1995 to 2008 (solar cycle SC 23) are used for the present study. The HILDCAA events were separated into storm-preceded HILDCAAs (SH) and non-storm or isolated HILDCAAs (H). The SH-events are those HILDCAAs which started after the end of geomagnetic storm main phase and occurred well inside the storm recovery phase. The geomagnetic storms preceding these SH-events were driven by CIRs as discussed previously. On the other hand, HILDCAAs not preceded by any storm main phase were also identified and are called H-events. Among the 43 events in this study, 11 were SH-events and 32 were H-events.

To study the magnetospheric energy budget, we estimated the kinetic energy of the solar wind, the magnetospheric energy input, as well as the dissipation of the energy in the inner magnetosphere-ionosphere system. The solar wind ram kinetic energy per unit time (U sw) is given by: N sw V sw 3 R CF 2. In this expression, N sw and V sw are the mass density and speed of the solar wind plasma, respectively. R CF is the distance from the Earth’s center to the subsolar location of dayside magnetopause, known as Chapman-Ferraro magnetopause distance (Chapman and Ferraro 1931; Ferraro 1952; Spreiter et al. 1966; Holzer and Slavin 1979; Sibeck et al. 1991; Monreal-MacMahon and Gonzalez 1997; Shue et al. 1997; Shue and Chao 2013). The energy transfer rate from the solar wind to the magnetosphere is estimated by the modified Akasofu epsilon parameter (ε*): V swBo2sin4(θ/2)R CF 2 (Perreault and Akasofu 1978), where Bo is the interplanetary magnetic field (IMF) magnitude and θ is the clock angle of the IMF orientation perpendicular to the Sun–Earth line (X-axis) in geocentric solar magnetospheric (GSM) coordinates. The magnetospheric input energy is dissipated within the magnetosphere/ionosphere system mainly by Joule heating, auroral precipitation, and ring current injection. The Joule heating rate (U J) is calculated using the Knipp et al. (2004) expression: a|PC| + bPC2 + c|SYM-H| + dSYM-H2, where PC is the polar cap potential index and SYM-H is the horizontal component of the symmetric ring current. The constants (a, b, c, and d) depend on the (northern hemispheric) seasons. To obtain a U J global estimate for both hemispheres, double northern hemispheric values are used for the equinoxes, while the summer and winter estimates are added for both summer and winter months. The auroral precipitation rate (U A) is obtained from NOAA/TIROS satellite measurements of high-latitude precipitating electron and ion fluxes with energies from 50 eV (or 300 eV) to 20 keV (Foster et al. 1986; Fuller-Rowell and Evans 1987; Emery et al. 2006). The global U A value is calculated by adding a southern hemisphere estimate to a northern hemisphere estimate. We assume the ring current energy injection rate (U R) to be dSYM-H*/dt + SYM-H*/τ (Akasofu 1981), where SYM-H* is the solar wind pressure corrected SYM-H index (Burton et al. 1975) with induced ground current and magnetotail current effects removed (Turner et al. 2001). In the above expression, τ is the average ring current decay time. This is taken as ~8 h for the present study (Yokoyama and Kamide 1997; Guo et al. 2011). The total input and dissipation energies, e.g., solar wind kinetic energy (E sw), magnetospheric input energy (Eε*), Joule dissipation energy (E J), auroral precipitation energy (E A), and ring current energy (E R), are calculated by time-integrating the power terms: U sw, ε*, U J, U A, and U R, respectively. It may be mentioned that the above-described methodology of estimation of magnetospheric/ionospheric energy budget has been previously used during geomagnetic storms, substorms, and HILDCAAs with good results (e.g., Turner et al. 2006, 2009; Guo et al. 2011, 2012; Hajra et al. 2014b).

The integrated fluxes of electrons with energy E > 0.6, E > 2.0, and E > 4.0 MeV at geosynchronous orbit (L = 6.6) are analyzed to study the radiation belt effects of HILDCAAs. The data (1-min time resolution) were measured by the Geostationary Operational Environment Satellite (GOES) instrumentation (Onsager et al. 1996). For more information, we refer the reader to http://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/stp/satellite/goes/dataaccess.html. Data for events during 1995–2002 are obtained from GOES-8 and those for 2003–2008 events from GOES-12. For the statistical analysis on the relativistic electron fluxes, running daily averages of the 1 min data are used in order to remove diurnal variations (e.g., Turner and Li 2008).

The Cluster 1 spacecraft is used to study possible occurrence of whistler-mode waves during its perigee passages through the magnetosphere (Santolik et al. 2014a) embedded inside the time intervals of HILDCAA events. We use continuous measurements of the Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Field Fluctuations–Spectrum Analyzer (STAFF-SA) instrument (Cornilleau-Wehrlin et al. 1997). The presence of whistler-mode emissions is identified from the measured power-spectral densities and from analysis of the wave polarization (Santolik et al. 2001, 2002; Santolik and Gurnett 2002). High-resolution waveform observations of the Wideband Data (WBD) instrument (Gurnett et al. 2001) have been used to verify presence of the discrete frequency–time structures of chorus wave packets (Santolik et al. 2014b).

The AE (1 min), Dst (1 h) and SYM-H (1-min resolution symmetric horizontal component of ring current/Dst) indices are obtained from the World Data Center for Geomagnetism, Kyoto, Japan (http://wdc.kugi.kyoto-u.ac.jp). The solar wind data (1-min resolution) are obtained from the OMNI website (http://omniweb.gsfc.nasa.gov). The latter data have already been time-shifted to coincide with solar wind convective times for impingement at the nose of the magnetopause.

Results

Event case studies

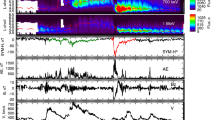

Figure 1 shows an example of solar wind/interplanetary variations as well as geomagnetic and radiation belt effects during a HILDCAA event on 6–10 June 2006. As denoted by the horizontal arrow in the AE panel, the event started at ~0602 UT on day 157 (6 June) and continued for ~4 days until ~0628 UT on day 161 (10 June). Initiation of the HILDCAA event (marked by the vertical dash-dot line) is associated with a CIR. The CIR is indicated by the compressed IMF Bo and compressed plasma density (not shown for brevity) from ~0417 UT on day 157 to ~1049 UT on day 158. In this case, the CIR did not cause a magnetic storm (SYM-H only reached a maximum of −44 nT). The CIR is followed by a HSS with peak speed V sw ~700 km s−1 at ~0900 UT on day 159 (8 June).

Solar wind/interplanetary dependence and geomagnetic/radiation belt effects during a HILDCAA event on 6–10 June 2006. From top to bottom, the panels show the frequency (Hz)-time (UT) spectrogram of the magnetic field component of the electromagnetic plasma waves (nT2 Hz−1) measured by the Cluster 1 spacecraft, the variations of E > 0.6 (E1), E > 2.0 (E2), and E > 4.0 MeV (E3) electron fluxes (cm−2 s−1 sr−1) from GOES-12, and solar wind speed (V sw in km s−1), IMF magnitude (Bo in nT), and Bz (nT) component in GSM coordinate system, and the SYM-H (nT) and AE (nT) indices, respectively. Perigee passes of Cluster 1 through the duskside magnetosphere are marked by black rectangles in the upper panel (close-up views are shown in Fig. 2). The horizontal arrow in the AE panel indicates the HILDCAA interval. The vertical dash-dot line shows the initiation time of the HILDCAA

The onset of the HILDCAA event coincides with a north-to-southward turning of the IMF Bz component, which is often a feature of HILDCAAs (Hajra et al. 2013, 2014c). The entire HILDCAA interval is characterized by high-frequency Bz variation between north and southward directions, which have been shown to be interplanetary Alfvén waves in many previous works (Tsurutani et al. 1985, 1990, 2011a, 2011b; Tsurutani and Gonzalez 1987; Echer et al. 2011).

The three panels below the topmost panel of Fig. 1 show the variations of the integrated electron fluxes (in unit of cm−2 s−1 sr−1, hereafter called flux unit, FU) at three energy levels: E > 0.6 MeV (E1), E > 2.0 MeV (E2), and E > 4.0 MeV (E3), respectively. The HILDCAA initiation time (the vertical dash-dot line) corresponds to an electron flux “dropout”. This dropout is most prominent for E > 0.6 MeV electrons. The E > 0.6 MeV electrons begin to increase at ~0343 UT on day 158 which is ~21.7 h after initiation of the HILDCAA (at ~0602 UT on day 157). The E > 2.0 MeV electrons start to increase ~1 day and 2 h after HILDCAA initiation. The E > 4.0 MeV electron fluxes begin to increase ~2 days and 22 h after HILDCAA initiation. During the HILDCAA interval, the E > 0.6, E > 2.0, and E > 4.0 MeV electron fluxes are enhanced by ~15, ~100, and ~2 times of the corresponding fluxes before the HILDCAA initiation.

The top panel of Fig. 1 shows the frequency–time spectrogram of the plasma wave magnetic field component measured by the Cluster 1 spacecraft during the HILDCAA interval. The regions marked by black rectangles show passages of Cluster 1 through the duskside magnetosphere. These are shown in high-resolution plots of Fig. 2. The first interval starts at ~0640 UT and ends at ~0800 UT on day 158 (7 June). The second passage starts at ~1510 UT and ends at ~1710 UT on day 160 (9 June). These intervals correspond to L ~ 4.1 to L ~ 5.9 and L ~ 4.2 to L ~11.3, respectively. The MLTs for these intervals were 17.8 to 18.7 and 19.0 to 18.1, respectively. Intense whistler-mode emissions are observed at frequencies between 40–50 Hz and 4 kHz by the STAFF-SA instrument. It is unusual to observe discrete chorus in this MLT sector, although observations of some discrete emissions have been also previously reported (Santolik et al. 2010a). WBD waveform measurements are unfortunately not available for the two analyzed time intervals. The detailed continuous STAFF-SA measurements show that rapid variations of wave intensity and divergent directions of the Poynting vector (Santolik 2008) are detected in both cases. During the second case (day 160), the wave spectra also exhibited an increase in frequency as the Cluster spacecraft moves inwards from L = 7 to L = 5.5, corresponding to chorus generation at a fraction of the electron cyclotron frequency (Tsurutani and Smith 1974; Meredith et al. 2001; Santolik et al. 2010b). This observed signature corresponds to properties of whistler-mode chorus and is strongly suggestive that these waves are indeed chorus. However, no high-resolution waveform data are available for this case, and therefore the existence of discrete chorus elements cannot be proven.

Figure 3 shows another example of a HILDCAA event occurring during 1–4 September 2007. The event had a duration of ~2 days, starting from ~1631 UT on day 244 (1 September) and ending at ~1710 UT on day 246 (3 September). The HILDCAA event initiation coincides with a CIR, and the HILDCAA interval corresponds well to an Alfvén wave train convected by a HSS event. The HSS had a peak V sw of ~690 km s−1 at ~2155 UT on day 245 (2 September). The E > 0.6 and E > 2.0 MeV electrons exhibit prominent flux enhancements during the HILDCAA interval compared to the corresponding pre-HILDCAA fluxes. Enhancement in the E > 4.0 MeV electron fluxes is noted at the end of the HILDCAA event. The fluxes for the E > 0.6, E > 2.0, and E > 4.0 MeV are ~12, ~55, and ~1.5 times the corresponding pre-HILDCAA flux levels, respectively. The top panel of Fig. 3 shows evidence of whistler-mode chorus waves between 30 Hz and 4 kHz which were observed during the passage of Cluster 1 through the dayside magnetosphere starting at ~0535 UT and lasting until ~0740 UT on day 245 (2 September). See Fig. 4 for high-resolution data. This interval corresponds to L ~ 3.1 to L ~ 13.1 and MLT of 14.3 to 12.4, a region where chorus is particularly intense (Tsurutani and Smith 1977; Meredith et al. 2001; Santolik et al. 2010a). The detailed continuous STAFF-SA measurements again show rapid variations of wave intensity, divergent directions of the Poynting vector, an increase in frequency as the Cluster spacecraft moves inwards from L = 11.4 to L = 4.4, and, subsequently, a decrease in frequency on the outbound pass from L = 5.2 to L = 13.1. High-resolution waveform measurements of the WBD instrument confirm the discrete nature of the whistler-mode chorus emissions in this case.

Solar wind/interplanetary dependence and geomagnetic/radiation belt effects during a HILDCAA event on 1–4 September 2007. From top to bottom, the panels show the frequency (Hz)–time (UT) spectrogram of the magnetic field component (nT2 Hz−1) of the electromagnetic plasma waves measured by the Cluster 1 spacecraft, the variations of E > 0.6 (E1), E > 2.0 (E2), and E > 4.0 MeV (E3) electron fluxes (cm−2 s−1 sr−1) from GOES-12, solar wind speed (V sw in km s−1), IMF magnitude (Bo in nT), and Bz (nT) component in GSM coordinate system, and the SYM-H (nT) and AE (nT) indices, respectively. The perigee pass of Cluster 1 through the dayside magnetosphere is marked by a black rectangle in the upper panel (close-up views are shown in Fig. 4). The horizontal arrow in the AE panel indicates the HILDCAA interval. The vertical dash-dot line shows the initiation time of the HILDCAA

CIR storm-preceded HILDCAAs and isolated HILDCAAs

As mentioned in the “Methods” section, we studied 43 HILDCAA events during SC 23, from 1995 through 2008. Among them, 11 events were preceded by CIR-induced geomagnetic storms (SH-events) and 32 were non-storm/isolated events (H-events). All the HILDCAA events were associated with enhanced fluxes at three energy levels, E > 0.6, E > 2.0, and E > 4.0 MeV, compared to pre-event fluxes. Whistler-mode chorus waves were detected for Cluster 1 perigee passes through the inner magnetosphere during HILDCAAs. In this section, we will show a comparative study on the SH- and H-events.

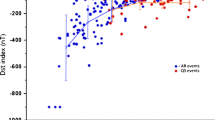

Figure 5 shows the results of superposed epoch analyses of E > 2.0 MeV electrons, IMF Bz, SYM-H, and AE indices separately for the SH- and H-events (red and blue curves, respectively). The initiation time of HILDCAA events is taken as the zero epoch time (t = 0 day). The variations of the parameters from 2 days before to 5 days after the initiation (zero epoch time) are shown.

Superposed epoch analyses during HILDCAA events. From top to bottom, the panels show the superposed time series of E > 2.0 MeV (E2) electron fluxes (cm−2 s−1 sr−1), IMF Bz (nT), SYM-H (nT), and AE (nT) indices during HILDCAA events. The red and blue curves correspond to isolated HILDCAAs (H) and CIR storm-preceded HILDCAAs (SH), respectively. The zero epoch time (indicated by the vertical line) corresponds to the initiation time of the HILDCAA events. The time axis is in the unit of 1 day. The numbers in the brackets in the title indicate the total number of H- and SH-events for the superposed epoch analyses

The variations of superposed geomagnetic indices (SYM-H and AE) display significantly different features before the event initiation (zero epoch time) and little differences during the event interval between the SH- and the H-events. For the SH-events, the geomagnetic activity as displayed in the variations of SYM-H (~−48 nT) and AE (~500 nT) is quite enhanced before zero epoch time due to the previous geomagnetic storm main phase. The low peak value of the superposed variation is due to the lack of coincidence of the peak storm phases of different storms. However, a signature of the end of storm main phase ~6 h prior to the HILDCAA initiation may be noted in the temporal display of the superposed SYM-H indices. For the H-events, variations of SYM-H and AE indicate weak enhancements of ring current and auroral activity only after zero epoch time (during the HILDCAA interval). The latter interval occurs after geomagnetic calm (Tsurutani et al. 1995). During the HILDCAA interval, the SYM-H and AE values are slightly enhanced for the SH-events (~−43 and 570 nT, respectively) over those for the H-events (~−27 and 530 nT, respectively).

Table 1 shows a comparison of the average and median intensity and duration of the SH- and H- events. IAE is the time-integrated AE intensity (in nT h), <AE> is the average intensity (in nT), and D is the duration (in days) of the HILDCAA events. All the characteristic parameters exhibited large ranges of variations for both SH- and H-events. The SH-events are found to be slightly stronger in intensity and longer in duration compared to the H-events. In the fourth column, we show the probability factor p based on Student’s t-statistics (Reiff 1990) in order to estimate the statistical significance of the mean characteristic parameters between the SH- and H-events. The events are considered to have significantly different characteristics if p < 0.05 (Press et al. 1992). Our result clearly suggests that the SH- and H- events do not have any statistically different characteristics.

The second panel of Fig. 5 shows the variation of IMF Bz for the SH- and H-events. In the variation of Bz, a small but significant southward component may be noted before the zero epoch time for the SH-events. This is responsible for the storm main phase. In the case of the H-events, Bz varied around 0 nT, consistent with the geomagnetic calm before event initiation, as mentioned earlier. Interestingly, the initiation of the H-events was preceded by (~3 h) prominent northward-to-southward turning of Bz. The southward Bz component (after zero epoch time) was comparatively stronger for the SH-events (peak Bz ~−2.5 nT) than for the H-events (peak Bz ~−1.9 nT). This may explain the comparatively enhanced ring current and auroral activity noted for the SH-events.

The top panel of Fig. 5 shows the variation of the E > 2.0 MeV electron fluxes. There is no significant difference in electron fluxes between the SH- and H-events. The E > 2.0 MeV electron flux curves for the SH- and H-events are quite similar to each other. In both cases, we note flux enhancements with time lags of ~1 day after the HILDCAA initiation time. The E > 0.6 and E > 4.0 MeV electron fluxes for the SH- and H-events are also similar to each other. The latter fluxes have not been shown in order to save space.

Magnetospheric and ionospheric energy deposition

We performed a comparative study on the energy budget of the SH- and H-events. Figure 6 shows the superposed variation of the different power components of solar wind-magnetosphere-ionosphere coupling: U sw, ε*, U J, U A, U R (see “Methods” section). The SYM-H and AE are repeated from Fig. 5 to give context to this figure. The solar wind kinetic energy input rate (U sw), magnetospheric energy input rate (ε*), as well as the rates of energy dissipation in the inner magnetosphere-ionosphere system (U J, U A, U R) are enhanced before zero epoch time (t = 0 day) for the SH-events compared to the H-events. This is because of larger energy input and dissipation rates during the geomagnetic storm main phases preceding the SH-events compared to those during geomagnetic quiet before the H-events. However, we can find no perceptible difference in the variation of the parameters between the SH- and H-HILDCAA intervals.

Superposed time series of solar wind-magnetosphere energy parameters during HILDCAA events. From top to bottom, the panels are the solar wind kinetic power (U sw in 1011 W), the solar wind-magnetosphere energy coupling function (ε* in 1011 W), the rates of Joule heating (U J in 1011 W), auroral precipitation (U A in 1011 W), and ring current injection energy (U R in 1011 W). The bottom two panels are the SYM-H (nT) and AE (nT) indices. The red and blue curves correspond to isolated HILDCAAs (H) and CIR storm-preceded HILDCAAs (SH), respectively. The zero epoch time (indicated by the vertical line) corresponds to the initiation time of the HILDCAA events. The time axis is in the unit of 1 day. The numbers in the brackets in the title indicate the total number of H- and SH-events for the superposed epoch analyses

In Table 2 we list the average and median values of the different energy components for the SH- and H-events. The p values are also noted for statistical significance test. The SH-events are characterized by slightly lower input energy and larger dissipation energy compared to the H-events. However, a quantitative assessment shows that the mean ring current dissipation is ~34 % higher for the storm-related events compared to the isolated events (p < 0.05), whereas Joule heating and auroral precipitation display no (statistically) distinguishable differences (p > 0.05).

Discussion

It has been previously shown that HILDCAA events that occur during HSSs are statistically related to relativistic electron acceleration (Hajra et al. 2013, 2014a, 2015). In this paper, we have studied HILDCAA intervals that are preceded by CIR magnetic storms and isolated (not preceded by storms) HILDCAA events for the first time. We have found virtually no differences in the relativistic electron flux characteristics between the two types of events. In fact, the only difference found is in the energetics of the ring current. There is more ring current energy associated with HILDCAAs that are preceded by CIR magnetic storms. It seems reasonable to assume that this is residual energy left over from the magnetic storms.

Hajra et al. (2015) have recently shown that electromagnetic chorus waves were present during HILDCAA intervals of SC 23 where there was Cluster plasma wave data available. In the present paper, we showed three examples of possible chorus waves detected during two HILDCAA events when Cluster 1 spacecraft passed through the inner magnetosphere. Individual HILDCAA events of this type have been previously shown by Tsurutani et al. (2006) and by Kasahara et al. (2009).

We follow the hypothesis of Tsurutani et al. (2010) for the acceleration of relativistic electrons within the magnetosphere. The southward component of the interplanetary Alfvén waves embedded within HSSs (Belcher and Davis 1971) leads to magnetic reconnection at the dayside magnetopause (Tsurutani et al. 1990, 1995). The ~10–100-keV anisotropic pitch angle electrons are injected into the midnight sector of the magnetosphere (DeForest and McIlwain 1971) and generate chorus (Tsurutani and Smith 1977; Inan et al. 1978; Meredith et al. 2003, 2006) by the loss cone/temperature anisotropy instability (Kennel and Petschek 1966; Tsurutani et al. 1979; Tsurutani and Lakhina 1997). The chorus then interacts with the upper energy end of the injected electrons, ~100 keV, to produce the ~MeV energies detected in the magnetosphere (Horne and Thorne 1998; Miyoshi et al. 2003; Omura et al. 2008; Reeves et al. 2013; Thorne et al. 2013; Boyd et al. 2014). The role of sporadic ~10–100-keV electron injection and continuous chorus generation is clearly critical to the process of relativistic electron acceleration. HILDCAA intervals, which are comprised of intense and continuous substorm/convection events, clearly provide such an environment. If a HILDCAA occurs in the HSS following the CIR storm, it appears to be occurring in the storm “recovery phase”. However, it has been shown that energy is sporadically pumped into the magnetosphere throughout HILDCAAs by the magnetic reconnection from the southward component of the Alfvén waves (Tsurutani et al. 1995, 2006; Soraas et al. 2003; Hajra et al. 2014a, b, 2015). Thus the magnetosphere is not “recovering” but is in a more or less steady state with fresh energy coming in and dissipation going on. The sporadic injections of energetic, anisotropic ~10–100-keV electrons will generate chorus waves more or less continuously.

Chorus generation is reported during geomagnetic storms (Horne and Thorne 1998; Summers et al. 1998, 2002; Meredith et al. 2002; Horne et al. 2003, 2005a, 2005b, 2007). However, the particle injections during storms are deeper into the magnetosphere (stronger convection electric fields) and last for only hours of duration. On the other hand, HSS HILDCAAs can last for days to weeks (Tsurutani et al. 1995; Hajra et al. 2013), and presumably, the chorus lasts that long as well.

The ~10–100-keV electron injection during HILDCAAs is somewhat shallow, involving only the outer portion of the magnetosphere (L ~ 5 to 7: Soraas et al. 2003) due to the relatively small convection electric fields (Tsurutani et al. 2006). Thus it is surmised that the electron acceleration is taking place at L values close to geosynchronous orbit. The NOAA GOES satellites might be in ideal locations to monitor events of this type.

Conclusions

The main conclusions of the present study may be summarized as follows:

-

1.

Two individual isolated HILDCAA events were shown to be related to relativistic E > 0.6, E > 2.0, and E > 4.0 MeV flux increases (Figs. 1 and 3). It was shown that intense whistler-mode chorus waves exist in the outer magnetosphere using simultaneous Cluster 1 satellite observations. This was typical of all of the isolated HILDCAA intervals that occurred during SC 23.

-

2.

A superposed epoch analysis of HILDCAAs with preceding CIR magnetic storms and isolated HILDCAAs indicated little or no differences in relativistic electron flux characteristics (Fig. 5).

-

3.

The solar wind energy input and the energy dissipation (Joule heating, auroral energy, and ring current energy) for CIR magnetic storm preceding HILDCAAs and for isolated HILDCAAs are virtually the same, except that CIR storm-preceded HILDCAA events have ~34 % higher ring current dissipation than isolated HILDCAA events (Fig. 6 and Table 2).

Abbreviations

- AE:

-

auroral electrojet

- CIR:

-

corotating interaction region

- FU:

-

flux unit

- GOES:

-

Geostationary Operational Environment Satellite

- GSM:

-

geocentric solar magnetospheric

- H:

-

HILDCAA (isolated)

- HILDCAA:

-

high-intensity long-duration continuous AE activity

- HSS:

-

high-speed solar wind stream

- IAE:

-

integrated AE

- IMF:

-

interplanetary magnetic field

- SH:

-

storm-preceded HILDCAA

- STAFF-SA:

-

Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Field Fluctuations–Spectrum Analyzer

- WBD:

-

Wideband Data

References

Akasofu SI (1981) Energy coupling between the solar wind and the magnetosphere. Space Sci Rev 28:121–190

Alves MV, Echer E, Gonzalez WD (2006) Geoeffectiveness of corotating interaction regions as measured by Dst index. J Geophys Res 111(A07S05). doi:10.1029/2005JA011379

Baker DN, Blake JB, Callis LB, Cummings JR, Hovestadt D, Kanekal S, Klecker B, Mewaldt RA, Zwickl RD (1994) Relativistic electron acceleration and decay time scales in the inner and outer radiation belts: SAMPEX. Geophys Res Lett 21:409–412

Balogh A, Bothmer V, Crooker NU, Forsyth RJ, Gloeckler G, Hewish A, Hilchenbach M, Kallenbach R, Klecker B, Linker JA, Lucek E, Mann G, Marsch E, Posner A, Richardson IG, Schmidt JM, Scholer M, Wang YM, Wimmer-Schweingruber RF, Aellig MR, Bochsler P, Hefti S, Mikić Z (1999) The solar origin of corotating interaction regions and their formation in the inner heliosphere. Space Sci Rev 89:141–178

Belcher JW, Davis L Jr (1971) Large-amplitude Alfvén waves in the interplanetary medium: 2. J Geophys Res 76:3534–3563. doi:10.1029/JA076i016p03534

Boyd AJ, Spence HE, Claudepierre SG, Fennell JF, Blake JB, Baker DN, Reeves GD, Turner DL (2014) Quantifying the radiation belt seed population in the March 17, 2013 electron acceleration event. Geophys Res Lett 41:2275–2281. doi:10.1002/2014GL059626

Burton RK, McPherron RL, Russell CT (1975) An empirical relationship between interplanetary conditions and Dst. J Geophys Res 80:4204–4214

Chapman S, Ferraro VCA (1931) A new theory of magnetic storms, part I, The initial phase. Terr Magn Atmos Electr 36:77–97

Cornilleau-Wehrlin N, Chauveau P, Louis S, Meyer A, Nappa JM, Perraut S, Rezeau L, Robert P, Roux A, De Villedary C, De Conchy Y, Friel L, Harvey CC, Hubert D, Lacombe C, Manning R, Wouters F, Lefeuvre F, Parrot M, Pinçon JL, Poirier B, Kofman W, Louarn P (1997) The Cluster Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Field Fluctuations (STAFF) experiment. Space Sci Rev 79:107–136

DeForest SE, McIlwain CE (1971) Plasma clouds in the magnetosphere. J Geophys Res 76:3587–3611. doi:10.1029/JA076i016p03587

Echer E, Tsurutani BT, Gonzalez WD, Kozyra JU (2011) High speed stream properties and related geomagnetic activity during the whole heliosphere interval (WHI): 20 March to 16 April 2008. Sol Phys 274:303–320. doi:10.1007/s11207-011-9739-0

Emery BA, Evans DS, Greer MS, Holeman E, Kadinsky-Cade K, Rich FJ, Xu W (2006) The low energy auroral electron and ion hemispheric power after NOAA and DMSP intersatellite adjustments. NCAR Scientific and Technical Report 470. https://cedarweb.vsp.ucar.edu/wiki/images/4/47/Str470.pdf

Ferraro VCA (1952) On the theory of the first phase of a geomagnetic storm: a new illustrative calculation based on an idealized (plane not cylindrical) model field distribution. J Geophys Res 57:15–49. doi:10.1029/JZ057i001p00015

Foster JC, Holt JM, Musgrove RG, Evans DS (1986) Ionospheric convection associated with discrete levels of particle precipitation. Geophys Res Lett 13:656–659

Fuller-Rowell TJ, Evans DS (1987) Height-integrated Pedersen and Hall conductivity patterns from the TIROS-NOAA satellite data. J Geophys Res 92:7606–7618

Gonzalez WD, Joselyn JA, Kamide Y, Kroehl HW, Rostoker G, Tsurutani BT, Vasyliunas VM (1994) What is a geomagnetic storm? J Geophys Res 99:5771–5792

Guo J, Feng X, Emery BA, Zhang J, Xiang C, Shen F, Song W (2011) Energy transfer during intense geomagnetic storms driven by interplanetary coronal mass ejections and their sheath regions. J Geophys Res 116(A05106). doi:10.1029/2011JA016490

Guo J, Feng X, Emery BA, Wang Y (2012) Efficiency of solar wind energy coupling to the ionosphere. J Geophys Res 117(A07303). doi:10.1029/2012JA017627.

Gurnett DA, Huff RL, Pickett JS, Persoon AM, Mutel RL, Christopher IW, Kletzing CA, Inan US, Martin WL, Bougeret JL, Alleyne HSC, Yearby KH (2001) First results from the Cluster wideband plasma wave investigation. Ann Geophys 19:1259–1272

Hajra R, Echer E, Tsurutani BT, Gonzalez WD (2013) Solar cycle dependence of high-intensity long-duration continuous AE activity (HILDCAA) events, relativistic electron predictors? J Geophys Res 118:5626–5638. doi:10.1002/jgra.50530

Hajra R, Tsurutani BT, Echer E, Gonzalez WD (2014a) Relativistic electron acceleration during high-intensity, long-duration, continuous AE activity (HILDCAA) events: solar cycle phase dependence. Geophys Res Lett 41:1876–1881. doi:10.1002/2014GL059383

Hajra R, Echer E, Tsurutani BT, Gonzalez WD (2014b) Solar wind-magnetosphere energy coupling efficiency and partitioning: HILDCAAs and preceding CIR storms during solar cycle 23. J Geophys Res 119:2675–2690. doi:10.1002/2013JA019646

Hajra R, Echer E, Tsurutani BT, Gonzalez WD (2014c) Superposed epoch analyses of HILDCAAs and their interplanetary drivers: solar cycle and seasonal dependences. J Atmos Sol Terr Phys 121:24–31

Hajra R, Tsurutani BT, Echer E, Gonzalez WD, Santolik O (2015) Relativistic (E > 0.6, > 2.0, and > 4.0 MeV) electron acceleration at geosynchronous orbit during high-intensity, long-duration, continuous AE activity (HILDCAA) events. ApJ 799:39–46. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/799/1/39

Holzer RE, Slavin JA (1979) A correlative study of magnetic flux transfer in the magnetosphere. J Geophys Res 84:2573–2578

Horne RB, Thorne RM (1998) Potential waves for relativistic electron scattering and stochastic acceleration during magnetic storms. Geophys Res Lett 25:3011–3014. doi:10.1029/98GL01002

Horne RB, Glauert SA, Thorne RM (2003) Resonant diffusion of radiation belt electrons by whistler-mode chorus. Geophys Res Lett 30(1493). doi:10.1029/2003GL016963.

Horne RB, Thorne RM, Glauert SA, Albert JM, Meredith NP, Anderson RR (2005a) Timescale for radiation belt electron acceleration by whistler mode chorus waves. J Geophys Res 110(A03225). doi:10.1029/2004JA010811

Horne RB, Thorne RM, Shprits YY, Meredith NP, Glauert SA, Smith AJ, Kanekal SG, Baker DN, Engebretson MJ, Posch JL, Spasojevic M, Inan US, Pickett JS, Decreau PME (2005b) Wave acceleration of electrons in the Van Allen radiation belts. Nature 437(7056):227–230. doi:10.1038/nature03939

Horne RB, Thorne RM, Glauert SA, Meredith NP, Pokhotelov D, Santolik O (2007) Electron acceleration in the Van Allen radiation belts by fast magnetosonic waves. Geophys Res Lett 34(L17107). doi:10.1029/2007GL030267

Horne RB, Lam MM, Green JC (2009) Energetic electron precipitation from the outer radiation belt during geomagnetic storms. Geophys Res Lett 36(L19104). doi:10.1029/2009GL040236

Inan US, Bell TF, Helliwell RA (1978) Nonlinear pitch angle scattering of energetic electrons by coherent VLF waves in the magnetosphere. J Geophys Res 83:3235–3253

Kasahara Y, Miyoshi Y, Omura Y, Verkhoglyadova OP, Nagano I, Kimura I, Tsurutani BT (2009) Simultaneous satellite observations of VLF chorus, hot and relativistic electrons in a magnetic storm “recovery” phase. Geophys Res Lett 36(L01106). doi:10.1029/2008GL036454

Kennel CF, Petschek HE (1966) Limit on stable trapped particle fluxes. J Geophys Res 71:1–28. doi:10.1029/JZ071i001p00001

Knipp DJ, Tobiska WK, Emery BA (2004) Direct and indirect thermospheric heating sources for solar cycles 21–23. Sol Phys 224:495–504

Li X, Baker DN, Temerin M, Cayton TE, Reeves EGD, Christensen RA, Blake JB, Looper MD, Nakamura R, Kanekal SG (1997) Multisatellite observations of the outer zone electron variation during the November 3–4, 1993, magnetic storm. J Geophys Res 102(A7):14123–14140. doi:10.1029/97JA01101

Meredith NP, Horne RB, Anderson RR (2001) Substorm dependence of chorus amplitudes: implications for the acceleration of electrons to relativistic energies. J Geophys Res 106(A7):13165–13178

Meredith NP, Horne RB, Iles RHA, Thorne RM, Heynderickx D, Anderson RR (2002) Outer zone relativistic electron acceleration associated with substorm-enhanced whistler mode chorus. J Geophys Res 107(1144). doi:10.1029/2001JA900146

Meredith NP, Cain M, Horne RB, Thorne RM, Summers D, Anderson RR (2003) Evidence for chorus-driven electron acceleration to relativistic energies from a survey of geomagnetically disturbed periods. J Geophys Res 108(1248). doi:10.1029/2002JA009764

Meredith NP, Horne RB, Glauert SA, Thorne RM, Summers D, Albert JM, Anderson RR (2006) Energetic outer zone electron loss timescales during low geomagnetic activity. J Geophys Res 111(A05212). doi:10.1029/2005JA011516

Miyoshi Y, Morioka A, Obara T, Misawa H, Nagai T, Kasahara Y (2003) Rebuilding process of the outer radiation belt during the 3 November 1993 magnetic storm: NOAA and Exos-D observations. J Geophys Res 108(1004). doi:10.1029/2001JA007542.

Monreal-MacMahon R, Gonzalez WD (1997) Energetics during the main phase of geomagnetic superstorms. J Geophys Res 102:14199–14207

Omura Y, Katoh Y, Summers D (2008) Theory and simulation of the generation of whistler-mode chorus. J Geophys Res 113(A04223). doi:10.1029/2007JA012622

Onsager T, Grubb R, Kunches J, Matheson L, Speich D, Zwickl RW, Sauer H (1996) Operational uses of the GOES energetic particle detectors. Proc SPIE 2812, GOES-8 and Beyond 281. doi:10.1117/12.254075

Onsager TG, Rostoker G, Kim HJ, Reeves GD, Obara T, Singer HJ, Smithtro C (2002) Radiation belt electron flux dropouts: local time, radial, and particle-energy dependence. J Geophys Res 107(A11). doi:10.1029/2001JA000187

Paulikas GA, Blake JB (1979) Effects of the solar wind on magnetospheric dynamics: energetic electrons at the synchronous orbit. In: Olsen W, Geophys Monogr Ser 21 (eds) Quantitative Modeling of Magnetospheric Processes. AGU, Washington, p 180

Perreault P, Akasofu SI (1978) A study of geomagnetic storms. Geophys J R Astron Soc 54:547–583

Pizzo VJ (1985) Interplanetary shocks on the large scale: a retrospective on the last decade's theoretical effects. In: Tsurutani BT, Stone RG, Geophys Monogr Ser 35 (eds) Collisionless Shocks in the Heliosphere: Reviews of Current Research. AGU, Washington, p 51. doi:10.1029/GM035p0051

Press WH, Teukolsky SA, Vetterling WT, Flannery BP (1992) Numerical recipes: the art of scientific computing, 2nd edn. Cambridge Univ Press, New York

Reeves GD, Spence HE, Henderson MG, Morley SK, Friedel RHW, Funsten HO, Baker DN, Kanekal SG, Blake JB, Fennell JF, Claudepierre SG, Thorne RM, Turner DL, Kletzing CA, Kurth WS, Larsen BA, Niehof JT (2013) Electron acceleration in the heart of the Van Allen radiation belts. Science 341:991–994. doi:10.1126/science.1237743

Reiff PH (1990) The use and misuse of statistics in space physics. J Geomagn Geoelectr 42:1145–1174

Santolik O (2008) New results of investigations of whistler-mode chorus emissions. Nonlin Proc Geophys 15:621–630

Santolik O, Gurnett DA (2002) Propagation of auroral hiss at high altitudes. Geophys Res Lett 29(1481). doi:10.1029/2001GL013666

Santolik O, Parrot M, Storey LRO, Pickett J, Gurnett DA (2001) Propagation analysis of plasmaspheric hiss using Polar PWI measurements. Geophys Res Lett 28:1127–1130

Santolik O, Pickett JS, Gurnett DA, Storey LRO (2002) Magnetic component of narrow-band ion cyclotron waves in the auroral zone. J Geophys Res 107(1444). doi:10.1029/2001JA000146

Santolik O, Gurnett DA, Pickett JS, Grimald S, Decreau PME, Parrot M, Cornilleau-Wehrlin N, El-Lemdani Mazouz F, Schriver D, Fazakerley A (2010a) Wave-particle interactions in the equatorial source region of whistler-mode emissions. J Geophys Res 115(A00F16). doi: 10.1029/2009JA015218

Santolik O, Pickett JS, Gurnett DA, Menietti JD, Tsurutani BT, Verkhoglyadova O (2010b) Survey of Poynting flux of whistler mode chorus in the outer zone. J Geophys Res 115(A00F13). doi:10.1029/2009JA014925

Santolik O, Macusova E, Kolmasova I, Cornilleau-Wehrlin N, de Conchy Y (2014a) Propagation of lower-band whistler-mode waves in the outer Van Allen belt: systematic analysis of 11 years of multi-component data from the Cluster spacecraft. Geophys Res Lett 41:2729–2737

Santolik O, Kletzing CA, Kurth WS, Hospodarsky GB, Bounds SR (2014b) Fine structure of large-amplitude chorus wave packets. Geophys Res Lett 41:293–299

Shue JH, Chao JK (2013) The role of enhanced thermal pressure in the earthward motion of the Earth's magnetopause. J Geophys Res 118:3017–3026 doi:10.1002/jgra.50290

Shue JH, Chao JK, Fu HC, Russell CT, Song P, Khurana KK, Singer HJ (1997) A new functional form to study the solar wind control of the magnetopause size and shape. J Geophys Res 102:9497–9511

Sibeck DG, Lopez RE, Roelof EC (1991) Solar wind control of the magnetopause shape, location and motion. J Geophys Res 96:5489–5495

Smith EJ, Wolfe JH (1976) Observations of interaction regions and corotating shocks between one and five AU: Pioneers 10 and 11. Geophys Res Lett 3:137–140. doi:10.1029/GL003i003p00137

Soraas F, Oksavik K, Aarsnes K, Evans DS, Greer MS (2003) Storm time equatorial belt – an “image” of RC behavior. Geophys Res Lett 30(2). doi:10.1029/2002GL015636

Spreiter JR, Summers AL, Alksne AY (1966) Hydromagnetic flow around the magnetosphere. Planet Space Sci 14:223–253

Summers D, Thorne RM, Xiao F (1998) Relativistic theory of wave-particle resonant diffusion with application to electron acceleration in the magnetosphere. J Geophys Res 103:20487–20500. doi:10.1029/98JA01740

Summers D, Ma C, Meredith NP, Horne RB, Thorne RM, Heynderickx D, Anderson RR (2002) Model of the energization of outer-zone electrons by whistler-mode chorus during the October 9, 1990 geomagnetic storm. Geophys Res Lett 29(2174). doi:10.1029/2002GL016039

Thorne RM, Li W, Ni B, Ma Q, Bortnik J, Chen L, Baker DN, Spence HE, Reeves GD, Henderson MG, Kletzing CA, Kurth WS, Hospodarsky GB, Blake JB, Fennell JF, Claudepierre SG, Kanekal SG (2013) Rapid local acceleration of relativistic radiation-belt electrons by magnetospheric chorus. Nature 504:411–414

Tsurutani BT, Gonzalez WD (1987) The cause of high-intensity long-duration continuous AE activity (HILDCAAs): Interplanetary Alfvén wave trains. Planet Space Sci 35:405–412

Tsurutani BT, Gonzalez WD (1997) The interplanetary causes of magnetic storms: a review. In: Tsurutani BT, Geophys Monogr Ser 98 (eds) Magnetic Storms. AGU, Washington, p 77. doi:10.1029/GM098p0077

Tsurutani BT, Lakhina GS (1997) Some basic concepts of wave-particle interactions in collisionless plasmas. Rev Geophys 35:491–501. doi:10.1029/97RG02200

Tsurutani BT, Smith EJ (1974) Postmidnight chorus: a substorm phenomenon. J Geophys Res 79:118–127

Tsurutani BT, Smith EJ (1977) Two types of magnetospheric ELF chorus and their substorm dependences. J Geophys Res 82:5112–5128. doi:10.1029/JA082i032p05112

Tsurutani BT, Smith EJ, West HI, Buck RM (1979) Chorus, energetic electrons and magnetospheric substorms. In: Palmadesso PJ, Papadopoulos K (eds) Waves Instabilities in Space Plasmas. D. Reidel, Norwell, p 55

Tsurutani BT, Slavin JA, Kamide Y, Zwickl RD, King JH, Russell CT (1985) Coupling between the solar wind and the magnetosphere: CDAW 6. J Geophys Res 90:1191–1199

Tsurutani BT, Gould T, Goldstein BE, Gonzalez WD, Sugiura M (1990) Interplanetary Alfvén waves and auroral (substorm) activity: IMP 8. J Geophys Res 95:2241–2252. doi:10.1029/JA095iA03p02241

Tsurutani BT, Gonzalez WD, Gonzalez ALC, Tang F, Arballo JK, Okada M (1995) Interplanetary origin of geomagnetic activity in the declining phase of the solar cycle. J Geophys Res 110:21717–21733

Tsurutani BT, Gonzalez WD, Gonzalez ALC, Guarnieri FL, Gopalswamy N, Grande M, Kamide Y, Kasahara Y, Lu G, Mann I, McPherron R, Soraas F, Vasyliunas V (2006) Corotating solar wind streams and recurrent geomagnetic activity: a review. J Geophys Res 111(A07S01). doi:10.1029/2005JA011273

Tsurutani BT, Horne RB, Pickett JS, Santolik O, Schriver D, Verkhoglyadova OP (2010) Introduction to the special section on Chorus: Chorus and its role in space weather. J Geophys Res 115(A00F01). doi:10.1029/2010JA015870

Tsurutani BT, Echer E, Guarnieri FL, Gonzalez WD (2011a) The properties of two solar wind high speed streams and related geomagnetic activity during the declining phase of solar cycle 23. J Atmos Sol Terr Phys 73:164–177

Tsurutani BT, Echer E, Gonzalez WD (2011b) The solar and interplanetary causes of the recent minimum in geomagnetic activity (MGA23): a combination of midlatitude small coronal holes, low IMF Bz variance, low solar wind speeds and low solar magnetic fields. Ann Geophys 29:839–849

Turner DL, Li X (2008) Quantitative forecast of relativistic electron flux at geosynchronous orbit based on low-energy electron flux. Space Weather 6(S05005). doi:10.1029/2007SW000354

Turner NE, Baker DN, Pulkkinen TI, Roeder JL, Fennell JF, Jordanova VK (2001) Energy content in the storm time ring current. J Geophys Res 106:19149–19156

Turner NE, Mitchell EJ, Knipp DJ, Emery BA (2006) Energetics of magnetic storms driven by corotating interaction regions: a study of geoeffectiveness. In: Tsurutani BT, Geophys Monogr Ser 167 (eds) Recurrent Magnetic Storms: Corotating Solar Wind Streams. AGU, Washington, p 113. doi:10.1029/167GM11

Turner NE, Cramer WD, Earles SK, Emery BA (2009) Geoefficiency and energy partitioning in CIR-driven and CME-driven storms. J Atmos Sol Terr Phys 71:1023–1031

Yokoyama N, Kamide Y (1997) Statistical nature of geomagnetic storms. J Geophys Res 102:14215–14222

Acknowledgements

The work of RH is financially supported by Fundacao de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de Sao Paulo (FAPESP) through post-doctoral research fellowship at INPE. EE would like to thank to the Brazilian CNPq (301233/2011-0) agency for financial support. Portions of this research were performed at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology under contract with NASA. The Arecibo Observatory is operated by SRI International in collaboration with the Universities Space Research Association and Universidade Metropolitana under a cooperative agreement with National Science Foundation, award number 1160876. OS acknowledges funding from Premium Academiae, and grants LH12231 and LH14010.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

BTT helped with the conceptual ideas for the paper and helped write the paper. RH did major parts of the analyses. OS did the Cluster data analysis. Other authors contributed in interpreting the results and writing the paper as well. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

RH is a post-doctoral research fellow at INPE, Brazil. He was a visiting research scientist at AO, Puerto Rico, during the preparation of the paper. BTT is a senior research scientist at JPL, USA. WDG is a senior research scientist at INPE, Brazil. EE and LEAV are scientists at INPE, Brazil. CGMB is a senior research scientist at AO, Puerto Rico. OS is a senior research scientist at IAP and professor at Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Hajra, R., Tsurutani, B.T., Echer, E. et al. Relativistic electron acceleration during HILDCAA events: are precursor CIR magnetic storms important?. Earth Planet Sp 67, 109 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-015-0280-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-015-0280-5