Abstract

Background

Despite a supportive evidence base and a push to implement, the uptake of early rehabilitation in critical care has been inconsistent. The objective of this study was to explore barriers and facilitators to early rehabilitation for critically ill patients receiving invasive mechanical ventilation.

Methods

Using the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) of behavior change, we conducted semi-structured interviews exploring barriers and facilitators to early rehabilitation among four purposively sampled ICU clinician groups (nurses, rehabilitation professionals, respiratory therapists, and physicians). The TDF is a comprehensive framework of 14 “construct domains,” synthesized from 33 theories of behavior that was developed to study determinants of behavior and to design interventions to improve evidence-based healthcare practice. A topic guide was developed and piloted based on the TDF and expert knowledge. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were content analyzed by coding items into domains and then synthesized into more specific, over-arching themes or “beliefs.” An expert consensus group used structured decision rules to classify beliefs as high, moderate, or low in importance.

Results

We interviewed 40 stakeholders from the four clinician groups and identified 135 separate beliefs. Of these, 19 were classified as high, 40 as moderate, and 76 of low importance as barriers or facilitators. All beliefs classified as highly important fell within one of seven TDF domains: skills, social/professional role and identity, beliefs about capabilities, beliefs about consequences, environmental context/resources, social influences, and behavioral regulation. Beliefs of lower importance fell under the following seven domains: knowledge; optimism; reinforcement; intention; goals; memory, attention, and decision processes; and emotion. Quantitative differences in stated beliefs about early rehabilitation between professional groups were not common.

Conclusions

This study identified important barriers and facilitators to early rehabilitation in critical care patients. Domains identified as important should be considered when designing interventions to increase uptake of early rehabilitation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Traditionally, critical illness involved a period of deep sedation and immobility. However, deep sedation can be harmful [1, 2], and critical illness is associated with significant muscle atrophy and weakness [3, 4]. Physical rehabilitation, initiated early in the course of critical illness, is an active area of research within critical care. Observational studies to date have demonstrated the safety and feasibility of early rehabilitation with critically ill patients [5,6,7,8] and successful implementation in single centers [9, 10]. Randomized trials, summarized in a recent systematic review [11], as well as two randomized trials, demonstrate improved patient-centered outcomes with early rehabilitation strategies [11,12,13].

Despite a supportive evidence base and a significant push to implement such practices [14,15,16], uptake of early rehabilitation has been at best inconsistent. Point prevalence studies have documented low levels of involvement of physical therapists in the intensive care unit (ICU) and low rates of implementation of rehabilitation [17, 18]. Prior work studying barriers to implementation of early rehabilitation strategies in the ICU has focused on resource issues and concerns about patient tolerance and safety primarily from the perspective of physical therapists and physicians, with minimal input from nurses and no input from respiratory therapists.

There is broader evidence that the translation of complex, evidence-based interventions into clinical practice is often a slow and haphazard process [19, 20]. It has been argued that implementation and clinician behavior change may be facilitated through the application of theory to systematically identify the hypothesized causal mechanisms and factors influencing clinical practice [21, 22]. The Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) [23, 24] of behavior change synthesizes constructs from 33 behavior change theories into 14 “construct domains,” or clusters of related constructs that may explain practice change or the absence of change (see Additional file 1). It has been applied as a framework for developing questionnaires and interview topic guides across a range of clinical contexts to systematically explore the barriers and facilitators to clinician behavior change [25, 26]. Each domain represents a range of related constructs that may influence clinician behavior. For example, the domain “social influences” encompasses overlapping constructs such as professional identity, boundaries, confidence, leadership, and organizational culture/climate.

This study explored clinician-reported barriers and facilitators to early physical rehabilitation in critically ill patients receiving invasive mechanical ventilation. Additionally, the study assessed relative importance of the identified barriers to early rehabilitation.

Methods

Study design

This was a semi-structured interview study, based on the TDF, of ICU clinicians’ perceptions of barriers and facilitators to early rehabilitation.

Participants

Participants were purposively sampled from one of four clinician groups: critical care nurses, physicians, respiratory therapists, and rehabilitation professionals (physical therapists and occupational therapists) to achieve diversity in terms of years of experience, academic versus non-academic work environment, leadership position, ICU size, and country of practice (USA/Canada). Participants had to work as independent practitioners primarily caring for adult patients and were required to identify critical care as a focus in their practice.

To achieve the goals of maximum variability sampling described above [27], we recruited from the “ICU Recovery Network” (IRN), an online interest group of clinicians interested in critical care rehabilitation and recovery from critical illness, and multiple professional associations and collaborative research groups.

Development of topic guide

A semi-structured interview topic guide was developed based on the TDF and expert knowledge from the author group. At least one question for each of the 14 domains of the TDF was included. The interview guide was drafted by two critical care clinicians (SLG and BHC) and two health psychologists with expertise in the TDF (JF and FL). Following feedback from the wider investigator team and piloting with one clinician from each of the four clinical groups, questions were revised to minimize duplication and enhance clarity, clinical relevance, and completeness.

To assess the extent to which the questions were likely to elicit responses related to each domain, the questions were independently coded into domains by a health psychologist with expertise in the TDF (AP). The reliability of this coding was assessed with Cohen’s kappa [28]. The final interview topic guide is available in Additional file 2.

All interviews were conducted by a single member of the study team (EK) by telephone. All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, checked for accuracy, and anonymized. EK had prior experience with semi-structured interviewing and received additional context-specific training through detailed review of and feedback on pilot interviews provided by ICU clinicians (SG and BC) and health psychologists with experience in semi-structured interviewing (FL and JF).

Analysis

Using NVivo (version 10), data were analyzed using content analysis [29]. All participant utterances within each transcript were assigned to TDF domains by one investigator (SG). Responses could be allocated to more than one domain. Initially, a sub-sample of 10% of transcripts was independently coded by a second investigator (FL) to assess inter-rater reliability using Cohen’s kappa. If Cohen’s kappa was less than 0.7, coding strategies were reviewed with a plan to review a further 10% of transcripts as necessary. Discrepancies were resolved through consultation with additional team members (BC, JF).

Following initial coding, participants’ responses across transcripts were compared within each domain. Responses that were thematically similar were grouped to inductively identify a “belief” relevant to early rehabilitation. Additional detail to illustrate these methods is provided in Additional file 3. Analysis of interviews was continued until saturation was achieved, with at least two additional interviews per group analyzed beyond that point [30]. We planned to analyze approximately equal numbers of participants in each group to simplify quantitative comparisons.

An expert consensus group comprising the wider investigator team met to review all domain and belief coding for clinical and theoretical face validity. In addition, to establish importance, the group collectively reviewed each belief with the following considered as evidence of importance: (1) high frequency of belief (more than half the participants), (2) any participant expression of importance (e.g., “it’s critical to educate the staff”), (3) discord among participants about belief as a barrier or facilitator, (4) differences between clinician groups in frequency by at least five participants, and (5) whether a belief was expressed spontaneously versus prompted by a direct question. Theoretical and empirical work supports the use of multiple methods to establish importance in barriers work [31]. This approach to understanding importance has been used in prior TDF work [32]. Beliefs were classified as “low importance” if zero or one of the five criteria was met and of moderate importance if two criteria were met. All other beliefs were classified as high importance. A detailed explanation of the criteria for assessing importance is found in Additional file 4.

Ethical considerations

This study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Board at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre (Reference # 015-2014). Participation in the study was voluntary, and all data were anonymized. Telephone consent was obtained from all participants and recorded by the research assistant (EK) on written consent forms for each participant.

Results

Participants

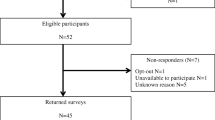

Forty participants were included. The denominator of potential participants is unknown because of the use of public listservs and email lists without known numbers. Saturation was achieved for each of the four clinician groups by a maximum of eight interviews. Interviews lasted a mean of 46 min (range 20–80 min). Participant details are shown in Table 1.

Inter-rater reliability

Cohen’s kappa for blinded assignment of questions to TDF domains was 0.89. Cohen’s kappa for duplicate coding of transcripts into TDF domains was 0.74.

Results by domain

A total of 135 beliefs related to early rehabilitation were identified across the 14 domains of the TDF. Of these, 19 were classified as high importance, 40 of moderate importance, and 76 of low importance as barriers or facilitators of early rehabilitation.

All beliefs classified as highly important fell within one of seven domains from the TDF: skills, social/professional role and identity, beliefs about capabilities, beliefs about consequences, environmental context and resources, social influences, and behavioral regulation. As shown in Fig. 1, domains with high importance beliefs also contained the highest number of beliefs identified. Beliefs of high importance are shown in Table 2 with exemplar quotations. Beliefs of moderate importance are shown in Additional file 5. High importance beliefs are elaborated below.

Skills

Participants reported that early rehabilitation was facilitated by working with experienced colleagues.

Social/professional role and identity

Underscoring the fact that early rehabilitation is a complex, team level behavior, a large number of specific roles were identified for multiple team members. In particular, physician roles as team leaders and as those who identify appropriate patients for rehabilitation were identified, although most frequently by the physician group rather than by other groups. The importance of a general “leadership role” for physicians was emphasized by all professional groups.

Beliefs about capabilities

Most participants reported that early rehabilitation was a difficult therapy to deliver (a potential barrier); however, some felt that it was fairly “easy” and fell within their skill sets as ICU clinicians.

Beliefs about consequences

Participants reported a broad range of benefits of early rehabilitation. In particular, improved strength or muscle mass, improved long-term function, improved mental health, and shorter duration of mechanical ventilation were identified as important.

Environmental context and resources

There was a range of views about the adequacy of staffing for early rehabilitation; some reported under-staffing as a barrier, while some felt staffing was adequate. There was similar diversity of views about whether “specialized” equipment was a facilitator. However, there were similar views both across and within professional groups that coordinating the various staff members and equipment needed at a time that was optimal for a patient was a barrier. There was also consistency in the belief that a model for early rehabilitation with physiotherapists specifically assigned to the ICU, rather than a rotating model was a facilitator.

Social influences

There was a frequently held view that local “champions” facilitated early rehabilitation. In addition to local champions, it was also reported by 6/10 physicians, 4/10 nurses, and 4/10 physical therapists, and none of the respiratory therapists that the support of ICU leadership was important. Family members were reported by all professional groups to influence early rehabilitation, although sometimes as a facilitator and sometimes as a barrier. All participants reported that discord or resistance from colleagues could be an important barrier to early rehabilitation.

Behavioral regulation

The importance of receiving feedback about early rehabilitation as a facilitator was noted by all groups; however, there was a range of views about whether or not feedback was actually received (a potential barrier). A unit protocol to guide early rehabilitation practice was reported by all groups as a facilitator.

Differences between professional groups

Quantitative differences in stated beliefs about early rehabilitation were not common (see Additional file 6). Eighteen of the 59 beliefs (31%) of at least moderate importance showed evidence of a difference in frequency between groups. In most cases (13/18, 72%), physicians were one of the two groups who differed. Most of the beliefs (13/18, 72%) fell under one of either social/professional role and identity, skills, or social influences. With social/professional roles, the differences were largely related to the roles of the participants assigned to their own professional group. For example, physicians frequently reported that they were responsible for goal setting, whereas physiotherapists did not identify this as a physician role.

The majority of physiotherapists reported the importance of practical experience for development of skills (7 of 10) compared with only 2 of 10 in each of the other professional groups (skills domain). Physicians (6 of 10) and nurses (5 of 10) reported the importance of “local champions” in early rehabilitation. In contrast, no members of the physiotherapy group reported this and only 1/10 of the respiratory therapy group did.

Discussion

This study used the TDF to study the beliefs of ICU clinicians regarding the barriers and facilitators to early rehabilitation in mechanically ventilated patients. We identified seven domains of the TDF which were most relevant to the behavior of clinicians and found that differences between clinician groups were uncommon. While the domains of environmental context and resources, as well as beliefs about consequences, are commonly identified in existing barriers literature [33,34,35,36,37], this approach facilitated a broader view of barriers and facilitators than prior literature. In particular, we demonstrated important factors not previously emphasized in the literature, in particular in the domains of social influences and behavioral regulation, which are novel findings in this field. These domains should be used to specifically direct implementation and quality improvement efforts.

For example, a recent cross-sectional study of hospital factors that influence early rehabilitation demonstrated that a formal protocol for early rehabilitation was associated with increased uptake [38], a strategy which falls under the domain of behavioral regulation. In a non-randomized interventional study, Hanekom et al. demonstrated that the introduction of a protocol for early rehabilitation increased frequency of rehabilitation sessions and reduced waiting time [39]. These findings, combined with our study showing the importance of the behavioral regulation domain, suggest that using a formal protocol to support early physical rehabilitation in the ICU setting may be helpful.

The domain of social influences, which we identified as important, is less frequently identified in the literature as a facilitator, although sometimes identified as a negative influence. We would suggest studies exploring specifically the role of “local champions” as a starting point, since our participants identified this as a useful facilitator.

Using a theoretically driven strategy provides potential for linkage to interventions for behavior change. Michie et al. have identified behavior change techniques and mapped them to theoretical domains as a starting point for the development of interventions [40]. For example, leveraging local opinion leaders may be a useful intervention to target the social influences domain [41].

A second advantage is to identify those domains that are less important so that efforts and resources can be focused away from those areas. For example, the knowledge domain was not found to contain a high number of beliefs in this study. Although the study sample was composed of volunteers and therefore may not be representative of all clinicians, this finding is consistent with prior knowledge translation research, which has shown only modest effects of educational interventions on clinician behavior [42,43,44].

The importance and level of elaboration of the domain social/professional role and identity was noteworthy in this study. TDF studies that investigate clinical behavior most often report beliefs about consequences (reflecting clinical thinking in terms of the balance between benefits and risks) as the most populated domain [45]. The importance of professional role in the current study provides a clear indication that team work and role clarity may be key to the implementation of early rehabilitation.

This study has a number of limitations. First, participants were volunteers recruited from online interest groups and professional organizations, which may create selection bias. A high number of participants reported determination to engage in early rehabilitation (intentions domain). In addition, within the domain of beliefs about consequences, participants endorsed a high number of specific positive associations with early rehabilitation. While supportive evidence exists, some of the specific beliefs endorsed by participants are not supported in the literature (e.g., mortality benefit). In addition, there was a commonly held belief that future literature would demonstrate further benefit (optimism domain). Participants may have experienced the equivalent of a “halo effect” [46], where a generally positive view of early rehabilitation creates a cognitive bias leading to other positive beliefs about early rehabilitation which may not be supported by evidence.

A second limitation is in the method by which we identified important beliefs and important domains. Our interviews generated a large volume of data, and it was necessary to try to identify those domains that were most important, in particular with the view that targeted interventions should be focused on those barriers and facilitators most likely to impact on early rehabilitation. We used a variety of methods to identify important domains based on work in prior literature [32], but it is not yet established that this method will lead to more successful interventions.

Conclusions

Using a theoretically driven approach, this study identified important barriers and facilitators to early rehabilitation in ICU patients. In particular, the domains of social influences and behavioral regulation were not previously well described in the literature. Future interventions should include interventions targeted at these domains, such as the institution of formal protocols to guide physical rehabilitation in the ICU. Differences between professional groups were uncommon but, where they exist, highlight the importance of involving an inter-professional team in implementation. Further work is required to validate our method for identifying importance and to determine the frequency of barriers and facilitators in other stakeholder groups.

Abbreviations

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IRN:

-

ICU Recovery Network

- TDF:

-

Theoretical Domains Framework

References

Pisani MA, Murphy TE, Araujo KL, Slattum P, Van Ness PH, Inouye SK. Benzodiazepine and opioid use and the duration of intensive care unit delirium in an older population. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(1):177–83.

Shehabi Y, Chan L, Kadiman S, Alias A, Ismail WN, Tan MA, Khoo TM, Ali SB, Saman MA, Shaltut A, et al. Sedation depth and long-term mortality in mechanically ventilated critically ill adults: a prospective longitudinal multicentre cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39(5):910–8.

De Jonghe B, Sharshar T, Lefaucheur JP, Authier FJ, Durand-Zaleski I, Boussarsar M, Cerf C, Renaud E, Mesrati F, Carlet J, et al. Paresis acquired in the intensive care unit: a prospective multicenter study. JAMA. 2002;288(22):2859–67.

Puthucheary ZA, Rawal J, McPhail M, Connolly B, Ratnayake G, Chan P, Hopkinson NS, Phadke R, Dew T, Sidhu PS, et al. Acute skeletal muscle wasting in critical illness. JAMA. 2013;310(15):1591–600.

Bailey P, Thomsen GE, Spuhler VJ, Blair R, Jewkes J, Bezdjian L, Veale K, Rodriquez L, Hopkins RO. Early activity is feasible and safe in respiratory failure patients. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(1):139–45.

Pohlman MC, Schweickert WD, Pohlman AS, Nigos C, Pawlik AJ, Esbrook CL, Spears L, Miller M, Franczyk M, Deprizio D, et al. Feasibility of physical and occupational therapy beginning from initiation of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(11):2089–94.

Denehy L, Skinner EH, Edbrooke L, Haines K, Warrillow S, Hawthorne G, Gough K, Hoorn SV, Morris ME, Berney S. Exercise rehabilitation for patients with critical illness: a randomized controlled trial with 12 months of follow-up. Critical Care (London, England). 2013;17(4):R156.

Sricharoenchai T, Parker AM, Zanni JM, Nelliot A, Dinglas VD, Needham DM. Safety of physical therapy interventions in critically ill patients: a single-center prospective evaluation of 1110 intensive care unit admissions. J Crit Care. 2014;29(3):395–400.

Needham DM, Korupolu R. Rehabilitation quality improvement in an intensive care unit setting: implementation of a quality improvement model. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2010;17(4):271–81.

Needham DM, Korupolu R, Zanni JM, Pradhan P, Colantuoni E, Palmer JB, Brower RG, Fan E. Early physical medicine and rehabilitation for patients with acute respiratory failure: a quality improvement project. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91(4):536–42.

Kayambu G, Boots R, Paratz J. Physical therapy for the critically ill in the ICU: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(6):1543–54.

Schaller SJ, Anstey M, Blobner M, Edrich T, Grabitz SD, Gradwohl-Matis I, Heim M, Houle T, Kurth T, Latronico N, et al. Early, goal-directed mobilisation in the surgical intensive care unit: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10052):1377–88.

Schweickert WD, Pohlman MC, Pohlman AS, Nigos C, Pawlik AJ, Esbrook CL, Spears L, Miller M, Franczyk M, Deprizio D, et al. Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9678):1874–82.

Gosselink R, Bott J, Johnson M, Dean E, Nava S, Norrenberg M, Schonhofer B, Stiller K, van de Leur H, Vincent JL. Physiotherapy for adult patients with critical illness: recommendations of the European Respiratory Society and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine Task Force on Physiotherapy for Critically Ill Patients. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(7):1188–99.

Sommers J, Engelbert RH, Dettling-Ihnenfeldt D, Gosselink R, Spronk PE, Nollet F, van der Schaaf M. Physiotherapy in the intensive care unit: an evidence-based, expert driven, practical statement and rehabilitation recommendations. Clin Rehabil. 2015;11:1051–63.

Tan T, Brett SJ, Stokes T. Rehabilitation after critical illness: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2009;338:b822.

Hodgin KE, Nordon-Craft A, McFann KK, Mealer ML, Moss M. Physical therapy utilization in intensive care units: results from a national survey. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(2):561–6. quiz 566-568

Nydahl P, Ruhl AP, Bartoszek G, Dubb R, Filipovic S, Flohr HJ, Kaltwasser A, Mende H, Rothaug O, Schuchhardt D, et al. Early mobilization of mechanically ventilated patients: a 1-day point-prevalence study in Germany*. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(5):1178–86.

Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G, Fraser C, Ramsay CR, Vale L, Whitty P, Eccles MP, Matowe L, Shirran L, et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8(6):iii–v. 1-72

Grol RPTM, Bosch MC, Hulscher MEJL, Eccles MP, Wensing M. Planning and studying improvement in patient care: the use of theoretical perspectives. Milbank Q. 2007;85(1):93–138.

Foy R, Ovretveit J, Shekelle PG, Pronovost PJ, Taylor SL, Dy S, Hempel S, McDonald KM, Rubenstein LV, Wachter RM. The role of theory in research to develop and evaluate the implementation of patient safety practices. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2011;20(5):453–9.

Michie S. Designing and implementing behaviour change interventions to improve population health. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2008;13:64–9.

Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7:17.

Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, Lawton R, Parker D, Walker A. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(1):26–33.

Cuthbertson BH, Campbell MK, MacLennan G, Duncan EM, Marshall AP, Wells EC, Prior ME, Todd L, Rose L, Seppelt IM, et al. Clinical stakeholders’ opinions on the use of selective decontamination of the digestive tract in critically ill patients in intensive care units: an international Delphi study. Crit Care. 2013;17(6):13.

Francis JJ, Tinmouth A, Stanworth SJ, Grimshaw JM, Johnston M, Hyde C, Stockton C, Brehaut JC, Fergusson D, Eccles MP. Using theories of behaviour to understand transfusion prescribing in three clinical contexts in two countries: development work for an implementation trial. Implement Sci. 2009;4:9.

Patton M. Purposeful sampling. In: Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Beverly Hills: Sage; 1990. p. 169–86.

Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–74.

Krippendorff K. Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2013.

Francis JJ, Johnston M, Robertson C, Glidewell L, Entwistle V, Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM. What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol Health. 2010;25(10):1229–45.

Francis JJ, Duncan EM, Prior ME, Maclennan G, Marshall AP, Wells EC, Todd L, Rose L, Campbell MK, Webster F, et al. Comparison of four methods for assessing the importance of attitudinal beliefs: an international Delphi study in intensive care settings. Br J Health Psychol. 2014;19(2):274–91.

Patey AM, Islam R, Francis JJ, Bryson GL, Grimshaw JM, Canada PPT. Anesthesiologists’ and surgeons’ perceptions about routine pre-operative testing in low-risk patients: application of the theoretical domains framework (TDF) to identify factors that influence physicians’ decisions to order pre-operative tests. Implement Sci. 2012;7:13.

Barber EA, Everard T, Holland AE, Tipping C, Bradley SJ, Hodgson CL. Barriers and facilitators to early mobilisation in intensive care: a qualitative study. Australian Critical Care. 2015;28(4):177–82.

Skinner EH, Berney S, Warrillow S, Denehy L. Rehabilitation and exercise prescription in Australian intensive care units. Physiotherapy. 2008;94:220–9.

King J, Crowe J. Mobilization practices in Canadian critical care units. Physiother Can. 1998;50(3):206–11.

Winkelman C, Peereboom K. Staff-perceived barriers and facilitators. Crit Care Nurse. 2010;30(2):S13–6.

Appleton RT, MacKinnon M, Booth MG, Wells J, Quasim T. Rehabilitation within Scottish intensive care units: a national survey. Journal of the Intensive Care Society. 2011;12(3):221–7.

Jolley SE, Caldwell E, Hough CL. Factors associated with receipt of physical therapy consultation in patients requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing. 2014;33(3):160–7.

Hanekom S, Louw QA, Coetzee AR. Implementation of a protocol facilitates evidence-based physiotherapy practice in intensive care units. Physiotherapy. 2013;99(2):139–45.

Michie S, Johnston M, Francis J, Hardeman W, Eccles M. From theory to intervention: mapping theoretically derived behavioural determinants to behaviour change techniques. Appl Psychol-Int Rev-Psychol Appl-Rev Int. 2008;57(4):660–80.

Flodgren G, Parmelli E, Doumit G, Gattellari M, O’Brien MA, Grimshaw J, Eccles MP. Local opinion leaders: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011;8:CD000125.

Farmer AP, Legare F, Turcot L, Grimshaw J, Harvey E, McGowan JL, Wolf F. Printed educational materials: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008;3:CD004398.

Forsetlund L, Bjorndal A, Rashidian A, Jamtvedt G, O’Brien MA, Wolf F, Davis D, Odgaard-Jensen J, Oxman AD. Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009;2:CD003030.

O’Brien MA, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G, Oxman AD, Odgaard-Jensen J, Kristoffersen DT, Forsetlund L, Bainbridge D, Freemantle N, Davis DA, et al. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007;4:CD000409.

Duncan EM, Francis JJ, Johnston M, Davey P, Maxwell S, McKay GA, McLay J, Ross S, Ryan C, Webb DJ, et al. Learning curves, taking instructions, and patient safety: using a theoretical domains framework in an interview study to investigate prescribing errors among trainee doctors. Implement Sci. 2012;7:13.

Nisbett RE, Wilson TD. The halo effect: evidence for unconscious alteration of judgments. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1977;35(4):250–56.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group for their support.

Funding

This study was funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Operating Grant.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to concerns about participant privacy. Although references to specific institutions have, to the best of our ability, been removed, there may be areas where participants have provided details in interviews about institutional characteristics that could be identified. Our participants did not consent to have full transcripts of their interviews made publicly available.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SLG, FL, BHC, and JJF conceived and designed the original study. EK completed the interviews. EK, SLG, and FL completed the coding. All authors participated in coding the validation and analysis. SLG and FL drafted the manuscript. All authors participated in revising the draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Board at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre. All participants provided explicit telephone consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Domains of the Theoretical Domains Framework. (DOCX 13 kb)

Additional file 2:

Topic Guide. (DOCX 16 kb)

Additional file 3:

Generation of TDF Domains and Beliefs. (DOCX 19 kb)

Additional file 4:

Criteria for Evaluating Importance of Beliefs. (DOCX 69 kb)

Additional file 5:

Beliefs of Moderate Importance. (DOCX 30 kb)

Additional file 6:

Frequency of all Beliefs by Profession. (DOCX 29 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Goddard, S.L., Lorencatto, F., Koo, E. et al. Barriers and facilitators to early rehabilitation in mechanically ventilated patients—a theory-driven interview study. j intensive care 6, 4 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-018-0273-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-018-0273-0