Abstract

Precisely changing the optical properties of gold nanoclusters (AuNCs) with different ligands offers a promising prospect for highly sensitive and selective drug sensing. In this study, AuNCs were synthesized with d-tryptophan (d-Trp) and its derivatives as the ligands. Optical measurements showed that d-Trp@AuNCs produced higher fluorescence intensity and shorter fluorescence emission wavelength than the d-Trp-derivatives-ligands protected AuNCs, indicating that the ligand-shell rigidity and core-shell charge transfer affected their fluorescent properties. At the excitation wavelength of 370 nm, the emission wavelength of d-Trp@AuNCs was 460 nm. The fluorescence changes revealed the high selectivity of d-Trp@AuNCs for detecting folic acid due to the static quenching and inner filter effect. In the presence of folic acid, the fluorescence of d-Trp@AuNCs was remarkably quenched with good linearity ranging from 6.3-100.0 μM (R2 = 0.997) and a detection limit of 5.8 μM. The proposed assay was successfully utilized to determine the amount of folic acid in human urine with recoveries from 94.3 to 107.3%. This work shows the great potential of d-Trp@AuNCs for detecting folic acid in real bio-samples. It also presents an effective strategy for preparation of the AuNCs with enhanced fluorescence efficiency by regulating the rigidity of the ligands shell and the core-shell charge transfer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Folic acid (FA), composed of pteridine, p-aminobenzoic acid and l-glutamic acid, is widely used for the treatment of megaloblasticanemias, and is an essential vitamin required for the healthy functioning of all cells (Mangas et al. 2004), and is especially important for pregnant women. FA deficiency leads to gigantocytic anemia, which is related to leukopenia, devolution of mentality and psychosis (Abdelwahab and Shim 2015; Zhao et al. 2006). Therefore, it is of practical significance to develop a selective and sensitive method to detect FA in human fluids.

Numerous approaches have been utilized for quantitative detection of FA, including high-performance liquid chromatography (Breithaupt 2001), electrochemical assays (Kalimuthu and John 2009), chemiluminescence (Wabaidur et al. 2013), and mass spectrometry (Pawlosky and Flanagan 2001). However, these protocols have disadvantages of the requirement for organic solvents and complicated operations (Breithaupt 2001; Kalimuthu and John 2009; Pawlosky and Flanagan 2001). Gold nanoclusters (AuNCs) have also been used to develop probes (Li et al. 2016; Luo et al. 2012; Cui et al. 2014; Porret et al. 2019; Sandeep et al. 2020) for use in the fluorescence detection of FA (Yan et al. 2015). In contrast to previous approaches, AuNCs have the advantages of simple, environmentally friendly synthesis, strong fluorescence emission, excellent biocompatibility, and light stability (You et al. 2018; Biji et al. 2010). For instance, with bovine serum albumin as the ligand, Hemmateenejad et al. (2014) synthesized AuNCs, which exhibited strong fluorescence at 629 nm for the detection of FA in pharmaceutical tablets. Meng et al. (2018) prepared AuNCs with strong fluorescence at 612 nm by using 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid as the ligand and used the probe to monitor FA in human serum samples. In previous studies, although some of the synthesis procedures were time-consuming, it indeed demonstrated that the use of different ligands as the reducing and stabilizing agents could result in different optical properties of the prepared AuNCs. This is because the fluorescence emission wavelength of the AuNCs is related to the chemical structure and the rigidity of the ligands: the more rigid the ligands, the longer the fluorescence emission wavelength of the AuNCs (Nandi et al. 2018). Additionally, it has been reported that the electron-rich ligands can donate their delocalized electrons to the gold core, which influences the fluorescence of AuNCs as strengthening the charge transfer from the ligand shell to the gold core can lead to improved AuNCs fluorescence emission efficiency (Wu and Jin 2010; Porret et al. 2019). Although these approaches have proved that the fluorescence intensity and emission wavelength of AuNCs can be tuned by the type of ligands, the synthesis of AuNCs with strong fluorescence by using d-amino acids and their derivatives as the ligands for highly selective monitoring of FA has not been explored until now.

This work exploited a simple “one-pot” strategy for the synthesis of AuNCs using d-tryptophan (d-Trp) and its derivatives, including d-tryptophan methyl ester (d-Trp-OMe), d-tryptophan benzyl ester (d-Trp-OBzl), and 1-methyl d-tryptophan (1-Me-d-Trp), as ligands. The effect of these ligands rigidity and charge transfer on their fluorescent properties was investigated for the first time. Among these AuNCs, d-Trp@AuNCs exhibited the highest fluorescence intensity with the maximum excitation and emission wavelengths at 370 nm and 460 nm, respectively. The highly selective sensing ability of d-Trp@AuNCs toward FA was examined by “turn-off” the fluorescence of the probe based on the static quenching and inner filter effect. Furthermore, urine samples were analyzed to justify the potential utility of d-Trp@AuNCs as the fluorescence turn-off probe for monitoring FA.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

d-Tryptophan (d-Trp) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, USA). d-Tryptophan methyl ester (d-Trp-OMe), d-tryptophan benzyl ester (d-Trp-OBzl), and 1-methyl-d-tryptophan (1-Me-d-Trp) were purchased from Aladdin Chemistry Company (Shanghai, China). Tetrachloroauric acid tetrahydrate (HAuCl4) was purchased from Shenyang Jinke Reagent Factory (Shenyang, China). Folic acid (FA) and tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Tris) were purchased from Yinuokai Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Other reagents were bought from Huixing Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All of the chemicals were of analytical grade and the water used throughout all experiments was purified by a Milli-Q system (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). Urine samples were donated by three healthy volunteers.

Instrumentation

The fluorescent spectra and intensity of all the samples were determined using an F-4500 fluorescence spectrometer (Hitachi, Japan). Ultraviolet-visible absorption spectra were measured with a TU-1900 UV-vis double-beam spectrometer (Purkinje General, China). Infrared spectra of d-Trp and d-Trp@AuNCs were measured by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR, TENSOR-27, Germany). Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images were observed with a transmission electron microscope (TECNAI G2 F20) (FEI, America) at a voltage of 200 kV. The Zeta electric potential of d-Trp@AuNCs and d-Trp@AuNCs-FA was monitored by dynamic light scattering (Malvern Instruments, United Kingdom). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Model ESCALAB250-XL) was conducted with a VG Thermo Fisher Scientific (USA) for getting Au 4f spectrum of the resultant d-Trp@AuNCs and d-Trp@AuNCs-FA. The fluorescence decay curve and lifetime (m0) of the d-Trp@AuNCs and d-Trp@AuNCs-FA were measured on an FLS980 spectrofluorimeter (Edinburgh, UK).

Method for synthesis of AuNCs

All of the glassware were thoroughly cleaned by using freshly prepared aqua regia (HCl:HNO3 volume ratio=3:1), and rinsed thoroughly in water. Briefly, 5.0 mL HAuCl4 (10.0 mM) was introduced to 10.0 mL d-Trp (10.0 mM) or d-Trp-OMe (10.0 mM) or d-Trp-OBzl (10.0 mM) or 1-Me-d-Trp (10.0 mM) solution under vigorous stirring at 100 °C and reacted for 1.0 h. Finally, the solution was purified by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 10.0 min and the supernatant was collected and stored at 4 °C for further use.

Method for preparation of buffer solutions

Different buffer solutions were prepared as follows: 10.0 mM NaH2PO4 solution was adjusted by 1.0 M HCl at pH ranging from 2.0 to 4.0; 10.0 mM NaH2PO4 solution was adjusted by 1.0 M NaOH at pH ranging from 5.0 to 6.0; 10.0 mM Tris solution was adjusted by 1.0 M HCl at pH from 7.0 to 9.0 (Zheng et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2019).

Method for detection of FA

Typically, 50.0 μL of FA solutions at different concentrations, 50.0 μL Tris-HCl buffer (10.0 mM, pH 7.0) and 200.0 μL of d-Trp@AuNCs were added into a microtube (1.0 mL). Then deionized water was added to dilute the final solution to 400.0 μL and the mixture was vortexed thoroughly. The resulting solutions were studied by fluorescence spectra from 390 nm to 600 nm with excitation at 370 nm.

The fluorescence intensity of the d-Trp@AuNCs changed with the addition of FA, which could be described by the Stern-Volmer equation (Alizadeh and Salimi 2019):

where F0 and F are the fluorescence intensities of the mixture in the presence and absence of FA, respectively. CFA is the concentration of quencher and Ksv is the Stern-Volmer constant.

The fluorescence quenching mechanism of d-Trp@AuNCs to FA could be represented by equation (2):

where Kq and τ0 are the quenching constant fluorescence lifetime of d-Trp@AuNCs, respectively.

Method for selective sensing of FA

The d-Trp@AuNCs was added into the solution with other coexisting compounds to test the selectivity of the d-Trp@AuNCs to FA. In total, 50.0 μL of other coexisting compounds, 50.0 μL Tris-HCl buffer (10.0 mM, pH 7.0), and 200.0 μL of d-Trp@AuNCs were added into a microtube (1.0 mL). Then deionized water was added to dilute the final solution to 400.0 μL and the mixture was vortexed thoroughly. The resulting solutions were measured by fluorescence spectra at room temperature.

Method for analysis of real samples

The diluted urine solutions were heated to boil for 20.0 min. Consequently, the samples were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10.0 min and the supernatants were collected for further analysis. Then, 50.0 μL of the urine supernatants, 50.0 μL of FA solutions, 50.0 μL of Tris-HCl buffer (10.0 mM, pH 7.0), 50.0 μL of deionized water, and 200.0 μL of d-Trp@AuNCs were added into a micro-plastic tube (1.0 mL). The mixture was monitored by fluorescence spectra.

Results and discussion

The influence of ligands on the fluorescent properties of AuNCs

Fluorescent AuNCs were prepared in one-pot using d-Trp and its derivatives (d-Trp-OBzl, d-Trp-OMe, and 1-Me-d-Trp), which have similar chemical structures, as ligands (Fig. S1). These AuNCs were varying shades of light yellow in daylight, and emitted blue fluorescence with different degrees of brightness under UV light (Fig. S2A). The d-Trp capped AuNCs possessed the highest fluorescence intensity (Fig. S2B), and the maximum emission wavelengths of d-Trp@AuNCs was 460 nm, 1-Me-d-Trp@AuNCs red shifted to 470 nm, while d-Trp-OBzl@AuNCs and d-Trp-OMe@AuNCs were in between (Fig. S1). According to a previous study (Nandi et al. 2018), the red shift of these AuNCs was assumed to be more or less related to the ligands shell rigidities. Compared with the other AuNCs, the ligand shell structure of d-Trp@AuNCs was more flexible, causing its fluorescence to blue shift (Fig. S2). While 1-Me-d-Trp@AuNCs displayed the lowest fluorescence intensity because the methyl group in the ligand structure affected the charge transfer between the N atom on the indole group and the gold core (Wu and Jin 2010). The decrease in fluorescence intensity of d-Trp-OMe@AuNCs and d-Trp-OBzl@AuNCs might be due to their large steric hindrance, which affected the formation of a compact ligand shell (Porret et al. 2019).

d-Trp-OMe@AuNCs and d-Trp-OBzl@AuNCs gave almost no response to 25.0 μM FA, while 1-Me-d-Trp@AuNCs gave no significant response to 75.0 μM FA (Fig. S3). In contrast, d-Trp@AuNCs produced a large response to 25.0 μM FA. These results were attributed to the differences in ligands structure (Zhang et al. 2020), affecting surface charge transfer from the shell to the gold core and, thereby, the sensitivity and selectivity of FA detection (Wu and Jin 2010). The surface electrostatic characteristics of these AuNCs were investigated to explain the phenomena. Fig. S4 shows that the Zeta potential of d-Trp@AuNCs in the presence and absence of FA was significantly higher than that of other AuNCs, indicating that d-Trp@AuNCs had stronger electrostatic interactions with FA. Finally, d-Trp@AuNCs was selected as the fluorescent probe to detect FA in further analysis.

Preparation and characterization of d-Trp@AuNCs

In order to synthesize d-Trp@AuNCs under suitable conditions, key factors affecting the fluorescence intensity of d-Trp@AuNCs were optimized, including the concentration of d-Trp and HAuCl4, the reaction time, and temperature. The strongest fluorescence intensity of d-Trp@AuNCs was obtained when 10.0 mM of d-Trp and HAuCl4 were used in the preparation process (Fig. S5A and S5B), following which optimization of the reaction temperature and duration revealed 100 °C and 1.0 h to give the best results (Fig. S5C and S5D).

d-Trp@AuNCs was prepared by using d-Trp as the reducing and protecting agent. The indole group of d-Trp can reduce Au3+ ions, reducing the Au3+ ions to form Au0 atoms (Selvakannan et al. 2004). The d-Trp@AuNCs was analyzed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), revealing binding energies at 90.5 eV (Au 4f5/2) and 84.8 eV (Au 4f7/2), as displayed in Fig. S6A. It also confirmed the presence of Au+ and Au0 in d-Trp@AuNCs (Casaletto et al. 2006). There is no obvious XPS changes that were found upon the addition of FA (Fig. S6B), showing that FA did not interact with Au.

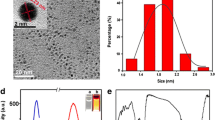

The resultant d-Trp@AuNCs formed a pale yellow aqueous solution under daylight (Fig. 1A (a)) and emitted strong blue fluorescence under UV light (Fig. 1A (b)) with the maximum excitation and emission wavelengths at 370 nm and 460 nm, respectively (Fig. 1A). Figure 1B depicts that there was no surface plasmon resonance band at around 500-600 nm, indicating that no large size of gold nanoparticles formed; the d-Trp@AuNCs was constructed successfully with small size. Furthermore, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging demonstrated that the d-Trp@AuNCs had regular spherical morphology and distributed evenly (Fig. 1C), with nanoparticles size of 2.8±0.4 nm.

Figure S7 exhibits the Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra of d-Trp@AuNCs. The absorption peak at 750 cm−1 was attributed to bending vibrations of the C-H groups of the d-Trp@AuNCs. The absorption peaks at 1738 cm−1, 3020 cm−1, and 3391 cm−1 corresponded to the stretching vibrations of the C=O, O-H and N-H groups of the d-Trp@AuNCs, respectively (Zheng et al. 2017). Additionally, the absorption peak of d-Trp@AuNCs at 3391 cm−1 was significantly different to that of d-Trp.

d-Trp can bond with Au through N-H in indolyl group. The empty orbital of Au and the lone pair of electrons of the N atom on the indole group of d-Trp combined to form a stable coordinated covalent bond. This resulted in the formation of d-Trp@AuNCs with d-Trp as the capping and reducing agent; this formation was confirmed by the results above.

Detection of FA with d-Trp@AuNCs as the fluorescent probe

Upon addition of FA into the aqueous d-Trp@AuNCs solution, a significant fluorescence intensity decrease was observed (Fig. 2A), as well as an obvious aggregation of d-Trp@AuNCs (Fig. 2B) accompanied by a dramatic enlargement of the nanoparticles size to 48.2±0.9 nm (insert of Fig. 2b). Figure 3 displays that the absorption spectra of FA were overlapped with the excitation spectra of the d-Trp@AuNCs. The fluorescence of the d-Trp@AuNCs was markedly quenched by FA via the inner filter effect (Liu et al. 2017). Moreover, the phenomena also could be explained by static quenching based on the Stern-Volmer equation (Fig. S8). The m0 was measured to be 11.9 ns (Fig. S8B). The Ksv and Kq were calculated to be 3.74×104 M−1 (Fig. S8A) and 3.14×1012 M−1S−1, respectively. The Kq value was much higher than that for dynamic quenching (1010 M−1S−1) (Alizadeh and Salimi 2019), indicating the static quenching mechanism of d-Trp@AuNCs to FA. Figure S8B also displays the fluorescence lifetime of d-Trp@AuNCs-FA almost no change (13.8 ns), revealing that there is no considerable excited-state interaction between d-Trp@AuNCs and FA. Moreover, Fig. 3 depicts the spectral overlap between the excitation spectrum of d-Trp@AuNCs and the absorbance spectrum of FA, indicating that the FA quenched the fluorescence of d-Trp@AuNCs due to the fluorescent inner filter effect (Liu et al. 2017).

Additionally, the Zeta potentials of the d-Trp@AuNCs and FA were +35.2 mV and −6.6 mV, respectively (Fig. S9), while after the addition of FA, the Zeta potential of d-Trp@AuNCs-FA changed to +15.6 mV. These results demonstrated that FA was indeed attached to the surface of d-Trp@AuNCs based on the electrostatic interactions. The proposed principle behind FA-mediated fluorescence quenching of d-Trp@AuNCs is illustrated in Fig. 4.

Next, the effects of solution pH, buffer ionic strength, and incubation time on the relative fluorescence intensity of d-Trp@AuNCs-FA/D-Trp@AuNCs (F/F0) were investigated because it has been reported that changing the buffer pH would change the probes fluorescence behavior (Meng et al. 2019) and healthy human fluids contain about 150.0 mM electrolytes (Pfäffli et al. 2016). Figure S10A indicates that the highest F/F0 value was obtained at buffer pH 7.0. It should be mentioned that the sizes of d-Trp@AuNCs-FA were measured to be 27.1 nm at pH 5.0 and 10.4 nm at pH 9.0, respectively. The Zeta potentials of d-Trp@AuNCs-FA were +5.8 mV at pH 5.0 and +11.1 mV at pH 9.0, respectively. Although these results displayed that changing the buffer pH would cause agglomeration of d-Trp@AuNCs-FA, the highest F/F0 value was obtained at buffer pH 7.0 (Fig. S10A). Importantly, considering that FA is more stable in neutral and weak basic conditions (Meng et al. 2018) than that in acidic solution, and the cations precipitate easily at basic solution (pH 8.0-11.0) in real samples (Vardhan et al. 2019); therefore, buffer pH at 7.0 was thus selected for further investigation. In addition, the F/F0 value remained unchanged even up to a sodium chloride concentration of 160.0 mM (Fig. S10B), and also when the incubation time changed from 2.0 to 5.0 min (Fig. S10C). These results depicted that the propose d-Trp@AuNCs could be applied in detection of FA in real human fluid samples. Furthermore, the strong fluorescence intensity could be maintained after storage of the fluorescent probe at 4 °C for 4 weeks (Fig. S11), exhibiting the long-term stability of the aqueous d-Trp@AuNCs.

There is always the potential for interferences to affect the probe’s performance by enhancing or decreasing its fluorescence intensity. To evaluate the performance of the d-Trp@AuNCs in the analysis of human urine, the fluorescence intensity of the d-Trp@AuNCs in the presence of common interfering substances, including Al3+, Ca2+, Cr3+, Fe2+, K+, Mg2+, Na+, Ni2+, Zn2+, l-Ala, l-Arg, l-Asp, l-Cys, l-Glu, l-His, l-Lys, l-Tyr, ascorbic acid (AA), glucose (Glu), and methotrexate (MTX), was measured. There is no significant changes that were observed in the fluorescence intensity of the d-Trp@AuNCs after introducing these compounds except FA (Fig. 5). The results indicated that the proposed protocol had high selectivity for sensing FA.

Selective test of the developed d-Trp@AuNCs for FA (100.0 μM) in the presence of potential interferents (25.0 μM): 1. Al3+, 2. Ca2+, 3. Cr3+, 4. Fe2+, 5. K+, 6. Mg2+, 7. Na+, 8. Ni2+, 9. Zn2+, 10. l-Ala, 11. l-Arg, 12. l-Asp, 13. l-Cys, 14. l-Glu, 15. l-His, 16. l-Lys, 17. l-Tyr, 18. AA, 19. Glu, 20. MTX, and 21. FA

The fluorescence intensity of the d-Trp@AuNCs decreased gradually with the increasing concentration of FA (Fig. 6B). Figure 6A shows the good linear correlation between the expression (F0-F)/F0 and the concentration of FA over the range of 6.3 to 100.0 μM, which could be expressed as (F0-F)/F0 = 4.2 × 10−3C+0.4 with a correlation coefficient R2 of 0.997 and the limit of detection around 5.8 μM. Compared with the reported AuNCs-based fluorescent probes (Table S1), the rapidly constructed d-Trp@AuNCs in this study performed well in the highly sensitive and selective sensing of FA in urine.

Quantitative detection of FA in urinary samples

To assess whether the proposed assay for detection of FA was applicable to real samples, human urine spiked with FA was analyzed. As shown in Table 1, the recovery of FA ranged from 94.3-107.3% with a good relative standard deviation (RSD < 3.0%), demonstrating the potential applicability of the d-Trp@AuNCs probe for monitoring of FA in real samples.

Conclusion

Fluorescent AuNCs were prepared using d-Trp and its derivatives including d-Trp-OMe, d-Trp-OBzl, and 1-Me-d-Trp as ligands. Of these, the chemical structure of d-Trp was found to be important in the superior optical properties exhibited by d-Trp@AuNCs. Further significant fluorescence enhancement could be achieved by reducing the rigidity of the d-Trp–based ligand-shell and increasing its core-shell charge transfer. Notably, the d-Trp@AuNCs exhibited high selectivity in the “turn-off” detection of FA due to the static quenching and inner filter effect. Additionally, successful application of the proposed fluorescence turn-off assay for analysis of FA in human urine samples was realized. This approach for obtaining higher fluorescence by changing the ligands-shell could be utilized for the preparation of other AuNCs. The highly fluorescent AuNCs offers promise for sensitive and selective detection, and opens new avenues in clinical drug applications.

Availability of data and materials

Research data have been provided in the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- FA:

-

Folic acid

- AuNCs:

-

Gold nanoclusters

- d-Trp:

-

d-Tryptophan

- d-Trp-OMe:

-

d-Tryptophan methyl ester

- d-Trp-OBzl:

-

d-Tryptophan benzyl ester

- 1-Me-d-Trp:

-

1-Methyl d-tryptophan

References

Abdelwahab AA, Shim Y. Simultaneous determination of ascorbic acid, dopamine, uric acid and folic acid based on activated graphene/MWCNT nanocomposite loaded Au nanoclusters. Sens. Actuators B. 2015;221:659–65.

Alizadeh N, Salimi A. Polymer dots as a novel probe for fluorescence sensing of dopamine and imaging in single living cell using droplet microfluidic platform. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2019;1091:40–9.

Biji P, Sarangi NK, Patnaik A. One pot hemimicellar synthesis of amphiphilic janus gold nanoclusters for novel electronic attributes. Langmuir. 2010;26:14047–57.

Breithaupt DE. Determination of folic acid by ion-pair RP-HPLC in vitamin-fortified fruit juices after solid-phase extraction. Food Chem. 2001;74:521–5.

Casaletto MP, Longo A, Martorana A, Prestianni A, Venezia AM. XPS study of supported gold catalysts: the role of Au0 and Au+δ species as active sites. Surf. Interface Anal. 2006;38:215–8.

Cui ML, Zhao Y, Song QJ. Synthesis, optical properties and applications of ultra-small luminescent gold nanoclusters. Trends Anal. Chem. 2014;57:73–82.

Hemmateenejad B, Shakerizadeh-shirazi F, Samari F. BSA-modified gold nanoclusters for sensing of folic acid. Sens. Actuators B. 2014;199:42–6.

Kalimuthu P, John SA. Selective electrochemical sensor for folic acid at physiological pH using ultrathin electropolymerized film of functionalized thiadiazole modified glassy carbon electrode. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2009;24:3575–80.

Li HC, Cheng YQ, Liu Y, Chen B. Fabrication of folic acid-sensitive gold nanoclusters for turn-on fluorescent imaging of overexpression of folate receptor in tumor cells. Talanta. 2016;158:118–24.

Liu HJ, Li M, Xia YN, Ren XQ. A turn-on fluorescent sensor for selective and sensitive detection of alkaline phosphatase activity with gold nanoclusters based on inner filter effect. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017;9:120–6.

Luo Z, Yuan X, Yu Y, Zhang Q, Leong DT, Lee JY, Xie J. From aggreagation-induced emission of Au(I)-thiolate complexes to ultrabright Au(0)@Au(I)-thiolate core-shell nanoclusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:16662–70.

Mangas A, Coveñas R, Geffard K, Geffard M, Marcos P, Insausti R, Dabadie MP. Folic acid in the monkey brain: an immunocytochemical study. Neurosci. Lett. 2004;362:258–61.

Meng FF, Gan F, Ye G. Bimetallic gold/silver nanoclusters as a fluorescent probe for detection of methotrexate and doxorubicin in serum. Microchim. Acta. 2019;186:1–8.

Meng L, Yin JH, Yuan YQ, Xu N. 11-Mercaptoundecanoic acid capped gold nanoclusters as a fluorescent probe for specific detection of folic acid via a ratiometric fluorescence strategy. RSC Adv. 2018;8:9327–33.

Nandi I, Chall S, Chowdhury S, Mitra T, Roy SS, Chattopadhyay K. Protein fibril-templated biomimetic synthesis of highly fluorescent gold nanoclusters and their applications in cysteine sensing. ACS Omega. 2018;3:7703–14.

Pawlosky RJ, Flanagan VP. A quantitative stable-isotope LC-MS method for the determination of folic acid in fortified foods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001;49:1282–6.

Pfäffli M, König S, Srivastava S. Synthetischer urin zusammensetzung und detection. Rechtsmedizin. 2016;2:103–8.

Porret E, Jourdan M, Gennaro B, Comby-Zerbino C, Bertorelle F, Trouillet V, Qiu X, Zoukimian C, Boturyn D, Hildebrandt N, Antoine R, Coll JL, Guevel XL. Influence of the spatial conformation of charged ligands on the optical properties of gold nanoclusters. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2019;123:26705–17.

Sandeep K, Manoj B, Thomas KG. Gold nanoparticle on semiconductor quantum dot: do surface liagnds influence Fermi level equilibration. J. Chem. Phys. 2020;152:044710.

Selvakannan PR, Mandal S, Phadtare S, Gole A, Pasricha R, Adyanthaya SD, Sastry M. Water-dispersible tryptophan-protected gold nanoparticles prepared by the spontaneous reduction of aqueous chloroaurate ions by the amino acid. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2004;269:97–102.

Vardhan KH, Kumar PS, Panda RC. A review on heavy metal pollution, toxicity and remedial measures: current trends and future perspectives. J. Mol. Liq. 2019;290:111197–218.

Wabaidur SM, Alam SM, Lee SH, Alothman ZA, Eldesoky GE. Chemiluminescence determination of folic acid by a flow injection analysis assembly. Spectrochim. Acta Part A. 2013;105:412–7.

Wu ZK, Jin RC. On the ligand’s role in the fluorescence of gold nanoclusters. Nano Lett. 2010;10:2568–73.

Yan X, Li HX, Cao BC, Ding ZY, Su XG. A highly sensitive dual-readout assay based on gold nanoclusters for folic acid detection. Microchim. Acta. 2015;182:1281–8.

You Q, Chen Y. Ultrabright, highly heat-stable gold nanoclusters through functional ligands and hydrothermally-induced luminescence enhancement. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2018;6:9703–12.

Zhang Z, Ye X, Liu Q, Liu Y, Liu R. Colorimetric detection of Cr3+ based on gold nanoparticles functionalized with 4-mercaptobenzoic acid. J. Anal. Sci. Technol. 2020;11:10.

Zhang ZP, Feng JY, Huang PC, Li S, Wu FY. Ratiometric fluorescent detection of phosphate in human serum with functionalized gold nanoclusters based on chelation-enhanced fluorescence. Sens. Actuators B. 2019;298:126891–6.

Zhao SL, Yuan HY, Xie C, Xiao D. Determination of folic acid by capillary electrophoresis with chemiluminescence detection. J. Chromatogr. A. 2006;1107:290–3.

Zheng SY, Yin HQ, Li Y, Bi FL, Gan F. One-step synthesis of L-tryptophan-stabilized dual-emission fluorescent gold nanoclusters and its application for Fe3+ sensing. Sens. Actuators B. 2017;242:469–75.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the Institute of Process Engineering, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for providing the TEM measurement.

Funding

The authors are grateful for the support from National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 21635008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LQ designed the research work. XFL and JQ synthesized AuNCs and finished the experimental studies and collection, analysis, and interpretation of experimental data. LQ and YJS wrote the manuscript. JQ and ZWL helped to revise the manuscript. All of the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary information

. Figure S1. Synthesis schematic illustration of AuNCs capped with D-Trp, D-Trp-OBzl, D-Trp-OMe and 1-Me-D-Trp, respectively. Figure S2. (A) Photographs of AuNCs capped with D-Trp (a), D-Trp-OMe (b), D-Trp-OBzl (c) and 1-Me-D-Trp (d) from left to right under daylight (upper row) and 365 nm UV irradiation (bottom row); (B) Fluorescence emission spectra of D-Trp@AuNCs (a), D-Trp-OMe@AuNCs (b), D-Trp-OBzl@AuNCs (c) and 1-Me-D-Trp@AuNCs (d). Figure S3. Fluorescence emission spectra of D-Trp-OMe@AuNCs (A), D-Trp-OBzl@AuNCs (B), 1-Me-D-Trp@AuNCs (C) and D-Trp@AuNCs (D) in the absence and presence of FA (a: 0.0 μM; b: 25.0 μM; c: 75.0 μM). Figure S4. The zeta potential difference of AuNCs in the absence and presence of FA: 1. D-Trp-OMe@AuNCs, 2. D-Trp-OBzl@AuNCs, 3. 1-Me-D-Trp@AuNCs and 4. D-Trp@AuNCs; where Z0 and Z are the potentials of AuNCs in the absence and presence of FA, respectively. Figure S5. Effects of concentrations of D-Trp (A), HAuCl4 (B), synthesis time (C) and synthesis temperature (D) on relative fluorescence intensity of the fluorescent probe. Figure S6. XPS spectra of Au 4f of D-Trp@AuNCs (A) and D-Trp@AuNCs-FA (B). Figure S7. FT-IR spectrum of D-Trp (a) and D-Trp@AuNCs (b). Figure S8. (A) Stern-Volmer plot of fluorescence quenching; (B) Fluorescence lifetime of D-Trp@AuNCs in the absence and presence of FA. Figure S9. The zeta potential of D-Trp@AuNCs, FA and D-Trp@AuNCs-FA (pH 7.0). Figure S10. Effects of pH (A); NaCl concentration (B) and incubation time (C) on F/ F0. Figure S11. Stability of the prepared D-Trp@AuNCs. Table S1. Comparison with the reported AuNCs for detection of FA

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., Qiao, J., Sun, Y. et al. Ligand-modulated synthesis of gold nanoclusters for sensitive and selective detection of folic acid. J Anal Sci Technol 12, 17 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40543-021-00266-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40543-021-00266-6