Abstract

Deep borehole heat exchangers (DBHEs) with depths exceeding 500 m have been researched comprehensively in the literature, focusing on both applications and subsurface modelling. This review focuses on conventional (vertical) DBHEs and provides a critical literature survey to analyse (i) methodologies for modelling; (ii) results from heat extraction modelling; (iii) results from modelling deep borehole thermal energy storage; (iv) results from heating and cooling models; and (v) real case studies. Numerical models generally compare well to analytical models whilst maintaining more flexibility, but often with increased computational resources. Whilst in-situ geological parameters cannot be readily modified without resorting to well stimulation techniques (e.g. hydraulic or chemical stimulation), engineering system parameters (such as mass flow rate of the heat transfer fluid) can be optimised to increase thermal yield and overall system performance, and minimise pressure drops. In this active research area, gaps remain, such as limited detailed studies into the effects of geological heterogeneity on heat extraction. Other less studied areas include: DBHE arrays, boundary conditions and modes of operation. A small number of studies have been conducted to investigate the potential for deep borehole thermal energy storage (BTES) and an overview of storage efficiency metrics is provided herein to bring consistency to the reporting of thermal energy storage performance of such systems. The modifications required to accommodate cooling loads are also presented. Finally, the active field of DBHE research is generating a growing number of case studies, particularly in areas with low-cost drilling supply chains or abandoned hydrocarbon or geothermal wells suitable for repurposing. Existing and planned projects are thus presented for conventional (vertical) DBHEs. Despite growing interest in this area of research, further work is needed to explore DBHE systems for cooling and thermal energy storage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Decarbonising heating and cooling is fundamental to realising a net-zero carbon emissions energy system (Carmichael 2019; Goldstein et al. 2020). Yet, space heating in the residential and public sectors continues to be sourced by natural gas (Goldstein et al. 2020), despite the availability of sustainable alternative heat sources. Geothermal energy has been demonstrated as one such feasible alternative to fossil-dominated heating and cooling (Durga et al. 2021; Gluyas et al. 2018). The geothermal energy sector has the potential to deliver baseload electricity generation, direct heating/cooling or by means of a heat pump, and thermal energy storage, independent of weather conditions. Conventional open-loop systems, for example, generate electricity using the heated fluid extracted from the reservoir via production wells. Heat transfer at surface subsequently drives power-producing generators, before the extracted fluid is then reinjected into the subsurface or disposed of at surface. To enhance subsurface flow pathways and well productivity, hydraulic and chemical stimulation of the reservoir can become necessary, thereby exposing such systems to risks such as induced seismicity (Pasqualetti 1980; Bayer et al. 2013). The high initial drilling cost coupled with high geological risk is seen as a further barrier to the adoption of hydrothermal geothermal systems, particularly Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS), at scale (Soltani et al. 2021).

Closed-loop systems provide an alternative to open-loop systems by removing direct hydraulic interactions with the reservoir. By operating using a single closed well design, conductive heat transfer between a heat transfer fluid and the surrounding geological formations is achieved through the borehole walls. Hence, the risk profile of closed-loop systems is considerably lower as the reliance on subsurface flow conditions is significantly reduced. Moreover, there is potential to offset the initial drilling cost by exploiting existing wells, such as abandoned oil and gas wells or failed geothermal exploration wells (Watson et al. 2020; Brown et al. 2024). As a trade-off to the minimised technical risks, heat transfer between the closed-loop system and the reservoir is restricted to conduction. A resulting far smaller volume of subsurface rock contributes to heat transfer. The reduced heat transfer potential limits the opportunities for electricity generation (Kolo et al. 2023) due to exergy losses and low conversion efficiencies (e.g. Alimonti et al. (2018, 2019); Renaud et al. (2019); Kolo et al. (2023); Chen et al. (2022); Alimonti et al. (2021)). Nonetheless closed-loop systems are well-placed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in direct or heat pump-mediated heating applications (Ball 2021).

Closed-loop systems are not restricted to heat extraction applications. Shallow borehole heat exchangers (BHE) have also been widely demonstrated to provide effective heat storage services. Given the transient nature of heating and cooling demand profiles, with seasonal and climatic dependency, thermal energy storage systems, such as borehole thermal energy storage (BTES), have been shown to reduce energy production demands by time-shifting sources of heat and coolth. By storing heat in, and subsequently extracting heat from the ground by closed-loop fluid circulation, the subsurface acts as a thermal battery. The mode of operation holds true for cold storage.

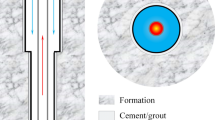

Closed-loop BHEs come in various configurations of either a U-tube or coaxial tube. Most shallow BHE systems (< 300 m) use single or double-U tubes but triple-U tubes are also available (Zarrella et al. 2013). Although U-tube configurations are reliable, cheap and easy to install, coaxial pipes are frequently chosen due to their low thermal resistance, despite their installation difficulty and susceptibility to leakage (Gehlin 2016). The selection of coaxial BHEs is more common in deeper borehole designs (see Fig. 1), as described later, in part due to the lower thermal resistance and pressure losses of this configuration over U-tube designs (Brown et al. 2024).

Schematic diagram showing a complete coaxial DBHE system (adapted from Kong et al. (2017)): a whole system; b coaxial tube; c thermal resistances (\(\text {R}_\bullet\)) for coaxial configuration used to describe the heat transfer coefficients (\(\Phi _\bullet\)) in the governing equations. It is noted that (\(\text {R}_\bullet\)) is a function of the heat transfer coefficient (\(\Phi _\bullet\)) expressed as a function of the borehole diameter (\(D_\text {BH}\)), external pipe (inner) diameter (\(D_\text {EP}\)) or internal pipe (inner) diameter (\(D_\text {IP}\))

The outer BHE pipe is commonly held in place, and thermally-connected to the surrounding rock matrix, via a grout medium. However, Scandinavian countries, characterised by hard crystalline rocks and high levels of groundwater (Skarphagen et al. 2019), typically leave BHEs ungrouted, thereby submerging the pipe(s) up to groundwater level. Through natural convection (i.e. an active groundwater flow in these semi-open BHE systems), heat transfer between BHE pipe and surrounding media can be enhanced (Gustafsson 2008).

In Deep BHE systems (DBHE)—classified herein as deeper than 500 m, as per the pre-existing UK Renewable Heat Incentive (Watson et al. 2020) and thus inclusive of the ‘middle-deep’ range considered in other works (Breede et al. 2015; Brown et al. 2024)—coaxial (concentric) pipes are mainly used due to issues related to strength and high hydraulic resistance (and thus unacceptably high parasitic pumping power) characteristic of narrow U tubes at high depths (Pan et al. 2019). Heat extraction via coaxial DBHEs operates by injecting a cold heat transfer fluid into the annulus or outer pipe (the CXA mode of operation), whilst gaining heat through conduction from the surrounding formation (Fig. 1). The heated fluid is extracted from the central or inner pipe and directed to the end-user (e.g. for space heating or greenhouse applications). The flow direction can be reversed when intending to inject heat into the surrounding subsurface media using the coaxial DBHE central pipe as the fluid inlet (the CXC mode of operation). Seasonally reversible combination of CXA and CXC is thus recommended for heat storage cycles comprising heat extraction and injection, as discussed further in "Thermal Energy Storage" section. Some practitioners have found, however, that practical considerations are far more important than the small marginal gains from reversing flow polarity in BTES systems (Heat pumps 2021; Brown et al. 2023). Further practical considerations include the requirement to increase flow rates as the depth of the BHE increases. This is necessary in order to maintain effective heat transfer and minimise thermal “short-circuiting” between inflow and outflow fluid streams. The BHE pipe cross-sectional area must increase respectively to avoid large pressure drops (Holmberg et al. 2016) and drilling costs are likely to increase as a result.

Given the range of space heating applications, DBHE systems have received significant interest in recent times as demonstrated by other published reviews on DBHE technology. For example, Sapinska-Sliwa et al. (2016) presented a conceptual review of installed DBHE systems around the world without comprehensively addressing numerical modelling studies. Alimonti et al. (2018) reviewed modelling of DBHE systems with a focus on their design and performance for heat and/or electricity generation. Advanced Geothermal System (AGS) technologies, to which DBHEs belong, have been reviewed by Budiono et al. (2022), but their work does not include deep BTES. This work therefore aims to provide a comprehensive review on numerical and analytical modelling of closed-loop conventional (vertical) DBHEs and their various applications in heating, cooling and storage, including those not captured by Sapinska-Sliwa et al. (2016). The review extends to describe a range of existing and planned projects. By comprehensively reviewing the applied and theoretical work in this research field, the work herein intends to elucidate remaining gaps and directions for future DBHE research.

Modelling approach

Experimental or pilot studies on DBHE systems are limited and research has tended to focus on analytical or numerical modelling studies, due to cost and time constraints (Jahangir et al. 2018; Bu et al. 2019). Analytical models work with simple geometries and use the Cartesian and cylindrical coordinate system of DBHE systems; however, insights from the full dimension can become important under complicated geological conditions (Skarphagen et al. 2019). For example, many quasi-three-dimensional analytical models assume a constant borehole temperature for the boreholes, but the effect of the geothermal gradient is an important consideration in deep boreholes (Pan et al. 2019). Analytical models struggle with combining geothermal gradient and heterogeneity in the subsurface formations. Also, it is difficult to get realistic values of borehole thermal resistance, because in DBHEs, thermal short-circuiting becomes more important (and flow rate dependent) and there may also be complex radial geometry to the borehole construction (several strings of casing and grout). It is worth noting that analytical models are more efficient in dealing with long year-on-year simulations, with complex (but annually repeating) heating loads. Numerical models are required to cope with the complexity ignored by analytical attempts, which can lead to long run-times. Different discretisation schemes have been used for subsurface numerical modelling of DBHE systems including finite element method (FEM)(e.g. Diersch (2013); Chen et al. (2019)), finite-difference method (FDM) (e.g. Brown et al. (2021)) and finite volume method (FVM) (e.g. Renaud et al. (2019)).

Governing equations

To model DBHE systems, two processes have to be described: heat and mass transport in (i) the surrounding subsurface and (ii) the DBHE pipes. It is important to quantify the heat flux exchange between the surrounding subsurface and DBHE pipes. Therefore, three sets of governing equations have to be included—(a) mass and energy conservation in the surrounding subsurface; (b) mass and energy conservation in the DBHE pipes; (c) heat flux coupling between DBHE pipes and surrounding subsurface.

Mass and energy conservation equations in surrounding subsurface

Considering the surrounding subsurface as a porous medium, the mass conservation equation can be written as

where S is the constrained specific storage (1/Pa) and \(\textbf{v}_\text {w}\) is the Darcy’s velocity (m/s) that is given by

where \(\textbf{k}\) is the permeability (tensor) of the porous medium (\(\hbox {m}^{2}\)), \(\mu\) is the dynamic viscosity (Pa s), \(\rho _\text {w}\) is the water density (\(\hbox {kg}/\hbox {m}^{3}\)) and \(\textbf{g}\) is the gravitational acceleration vector.

If there are fractures in the surrounding subsurface, the mass conservation equation should include the fracture effect (Deng et al. 2023). The fracture flow can be described in general as

where b is the fracture aperture (m), \(S_\text {frac}\) is the specific storage of fracture (1/Pa) and \(\textbf{v}_\text {frac}\) is the Darcy velocity in the fracture (m/s) that can be calculated according to the cubic law (He et al. 2021),

The surrounding subsurface temperature \(T_\text {s}\) is determined by the following energy conservation equation considering both heat convection and conduction in porous media,

where \(c_\text {s}\) is the solid mineral phase specific heat capacity, \(\rho _\text {s}\) is the solid mineral phase density and \(\epsilon\) is the rock porosity. \(c_\text {w}\), \(\rho _\text {w}\), and \(\textbf{v}_\text {w}\) refer to the specific heat capacity, density, and velocity of groundwater, respectively. \({\Lambda _\text {s}}\) denotes the tensor of thermal dispersion and \(H_\text {s}\) represents the heat source or sink terms.

In analogy to the hydraulic mass balance equation in fractures, the heat transport equation also needs to be multiplied by the fracture aperture b accordingly when there is fractured media in the surrounding subsurface. The velocity in the fractures is calculated according to the cubic law and the Darcy law as shown in Eq. (4). When considering the various thermal properties in the subsurface groundwater, such as density, viscosity, thermal conductivity, and specific heat capacity, the water equation of state based on the International Association for the Properties of Water and Steam (IAPWS-IF97) (Wagner and Kretzschmar 2007) can be further applied in the models.

Mass and energy conservation equations in DBHE pipes

When analysing mass conservation in DBHE pipes, most studies assumed that the total flow rate of the circulation fluid is constant. Therefore, no additional mass conservation equation needs to be considered. In this case, the thermosiphon effect caused by variable-density process in DBHE pipes cannot be simulated. When the DBHE systems are very deep or of high temperatures with significant variable thermal properties, Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) techniques and models have to be applied in the DBHE coaxial pipes, e.g. Renaud et al. (2019); Doran et al. (2021); Hu et al. (2021); Alimonti et al. (2021). In this method, the fluid flow in the DBHE pipes is governed by general equations of mass and momentum continuity:

where A is the cross-sectional area of the pipe (\({\hbox {m}^2}\)), and \(\textbf{v}_\text {f}\) refers to the cross-section averaged velocity vector in the DBHE pipes. \(\tau\) (Pa) is the viscous stress tensor and \(\textbf{F}\) (\({\hbox {N/m}^3}\)) is the volume force (i.e. gravity force).

From the energy conservation principle, the governing equation of the circulation fluid inside the inner and outer pipes can be written as

where \(\rho _\text {f}\), \(c_\text {f}\) refer to the density and specific heat capacity of the circulation fluid. The symbols \(\textbf{v}_k \ (k = i, o)\) denotes the flow velocity of inner (i) and outer (o) pipes of the DBHE. The symbol H is the heat sink/source term. The thermal dispersion tensor \(\Lambda _\text {f}\) is defined as

where \(\beta _\text {L}\) denotes the longitudinal heat dispersivity and \(\textbf{I}\) refers to the identity matrix. \(\textbf{v}_\text {f}\) is the circulation fluid velocity, \(\lambda _\text {f}\) is the thermal conductivity of the circulation fluid.

Generally, the coaxial pipe is embedded and fixed inside the borehole by a grout material to enhance the thermal exchange area and efficiency as shown in Fig. 1. Assuming that heat convection within the grout is negligible, the grout temperature (\(T_\text {g}\)) is governed by the heat conduction equation:

where the subscript g represents the grout component inside the borehole.

Heat flux coupling between DBHE pipes and surrounding subsurface

In closed-loop DBHE systems, it is assumed that no mass of circulation fluid inside the DBHE pipes will be in contact with the surrounding subsurface; there is only conductive heat exchange. Thus, the first important coupling term is the heat flux exchange between the grout material (if existent) and the surrounding subsurface. The dynamic coupling heat flux (\(q_{n T_\text {gs}}\)) can be quantified by the following equation (using Cauchy-type boundary condition):

where \({\Gamma _\text {s}}\) and \(\Phi _\text {gs}\) are the boundary and the heat transfer coefficient between the borehole grout and surrounding subsurface, respectively, see Fig. 1.

The heat flux exchange for the component of the grout (\(q_{n T_\text {g}}\)) includes two parts: one is the exchange with surrounding formation, and the other is the exchange with the inflow fluid in the annulus pipe in the CXA configuration. The total heat flux can be then expressed as

where, \({\Phi _\text {fig}}\) denotes the heat transfer coefficient between the outer pipe and grout (Fig. 1).

For the coaxial pipes in the DBHE system, the heat flux (\(q_{nT_\text {i}}\)) between the grout material and the circulation fluid in the outer pipe, and the heat flux (\(q_{nT_\text {o}}\)) between the circulation fluid in the outer and inner pipes can be expressed as

where \({\Phi _\text {ff}}\) refers to the heat transfer coefficient between the circulation fluid in inner and outer pipes, and \(\Gamma\) is the heat transfer boundary, subscripts i and o denote the inflow fluid in the annulus pipe and outflow fluid in the inner pipe, respectively.

There are multiple expressions for the heat transfer coefficient \(\Phi _\text {gs}\), \({\Phi _\text {fig}}\), and \({\Phi _\text {ff}}\); the widely used method is so-called thermal resistance and capacity model (TRCM) introduced by Bauer et al. (2011) and further implemented in numerical models by Diersch et al. (2011) and Chen et al. (2019). These heat transfer coefficients are strongly dependent on the pipe geometry, thermal properties of the circulation fluid and the flow state, leading to local non-equilibrium and global non-linear problems and thus posing challenges for the transient simulation. For example, as shown in Fig. 1, the heat transfer coefficients (\(\Phi\)) are a function of thermal resistances (R), see Diersch et al. (2011) for the detailed computation of thermal resistance. In addition, for the thermal properties of the circulation fluid in the closed loop, the open source package CoolProp can be used to calculate pure and pseudo-pure fluid equations of state and transport properties for 122 components (Bell et al. 2014). It is noted that single-phase liquid flow has been assumed for the circulating water as this is phase at the temperatures and pressures encountered for DBHEs. Moreover, according to Chen et al. (2019), the variation in thermo-physical properties of water along the depth of a 2.6 km DBHE resulted in negligible effects making it reasonable to consider constant thermo-physical properties for the circulating water.

Analytical

The most widely used analytical tools for analysing heat transfer in DBHEs are Kelvin’s theory of heat sources and the Laplace transform method (Jaeger and Carslaw 1959). It is difficult to obtain analytical solutions directly to the governing equations presented earlier for general cases. Therefore, some assumptions and simplification must be made to avoid complex derivations and calculations when developing a mathematical model of the DBHE to be solved analytically. These assumptions and simplification can be mainly summarised as three points:

-

1.

Infinite or semi-infinite surrounding subsurface. In this case, the far-field temperature is the same as the initial temperature and fixed as the boundary condition for analytical solutions.

-

2.

Homogeneous groundwater flow. When the effect of groundwater is considered in the multi-layer subsurface with some or all of the layers having groundwater movement, the flow is generally assumed to be homogeneous and parallel to the ground surface.

-

3.

Constant and uniform thermal properties. The thermal properties of all materials remain constant within the investigated temperature range. Only heat transport equations are solved analytically, mass conservation equation inside the coaxial pipe is not taken into account.

The first assumption is the basis for all the analytical solutions and is widely used from infinite line-source (Ingersoll 1950), infinite cylindrical source (Kavanaugh 1985) and finite line source (Eskilson 1987), to more advanced analytical solutions with various heat flux segment (Luo et al. 2019) and including geothermal gradient effect (Beier 2020). The second assumption is commonly applied in shallow BHE systems rather than DBHEs. For example, Diao et al. (2004) extended the infinite line source solution under homogeneous groundwater convection over the whole shallow BHE domain. In cases where the BHE penetrates the entire depth of the 3D porous medium, the analytical solution proposed by Molina-Giraldo et al. (2011) was applied to solve the spatio-temporal distribution of the induced ground temperature change. Hu (2017) also improved the infinite line source solution to investigate the effect of groundwater flow in multiple-layer geologies in a shallow BHE system. However, when the DBHE system is surrounded by fractured media or very heterogeneous porous media of inclined aquifers, this assumption limits the analytical modelling of single DBHE and multiple DBHE array. For example, although Luo et al. (2022) applied stratified-seepage-segmented finite line source method to semi-analytically model the DBHE system with multiple groundwater layers, the model could not simultaneously couple the effects of geothermal gradient, subsurface stratification and groundwater flow. In more recent analytical solutions, another strategy is adopted where the unit-step temperature response of the surrounding subsurface (i.e. G-function) is calculated together with the coaxial pipe inside the DBHE to have the temperature values inside the coaxial pipe. However, the usage of superposition principle restricts the analytical solution to linear physics (Li and Lai 2015). As for the third assumption, it will become unreasonable when the coaxial DBHE system goes deeper with larger pressure and temperature variation in the operation because of the heterogeneous heat transfer coefficients between pipes.

In some advanced analytical solutions, Beier (2020) improved upon the analytical solution presented in Beier et al. (2014) to include the influence of the geothermal gradient under variable heat extraction rates. The improved solution relied on the Stehfest (Stehfest 1970) algorithm to numerically perform an inverse Laplace transform and calculate temperatures in the time domain. Later, Beier et al. (2022) extended the analytical solution to a more advanced semi-analytical solution to include multiple ground layers and the geothermal gradient. Other examples of analytical solutions used to investigate heat extraction performance and analyse the influence of different parameters are those presented by Pan et al. (2019) and Pan et al. (2020). Additionally, some commercially-available software packages rely on analytical solutions to achieve fast computations and efficiency when designing ground loop heat exchangers. For example, Earth Energy Designer (EED 2021) and Ground Loop Heat Exchanger Design Software (GLHEPRO) (Cullin et al. 2015; Ground Loop 2023), specifically suited for designing shallow BHEs, account for the geothermal gradient by effectively setting the initial rock temperature as equal to the average temperature over the borehole depth (Eskilson 1987). However, key limitations to the analytical approach persist in its incapability to simulate i) complex boundary conditions and geological settings, ii) the impact of heterogeneous groundwater flow, and iii) non-constant thermal properties, especially for DBHE systems.

Numerical

Different numerical discretisation methods have been successfully adopted to model the heat transport process in coaxial DBHEs and their surrounding formation, including the FDM, FVM and FEM. Since the depth of a DBHE system can reach several thousand metres, cm-scale components inside the borehole will significantly increase the number of elements in the numerical model. Therefore, different numerical strategies have been devised (see Table 1) that can generally be divided into three main types:

-

1.

Dual-continuum methods: A 1D discretisation for the DBHE is combined with a 3D discretisation for the surrounding formation. The approach was originally proposed by Al-Khoury et al. (2010) and extended in FEFLOW software by Diersch et al. (2011a), Diersch (2013), and Diersch et al. (2011b). Thereafter, Chen (2022) developed and presented two deep closed-loop borehole heat exchanger models implemented in the OpenGeoSys (OGS) software using the dual-continuum FEM method. Kong et al. (2017), Chen et al. (2019), Cai et al. (2022), and Kolo et al. (2023) compared the numerical results simulated by this implementation with Beier’s analytical solution (Beier 2020), showing a very close match with temperature differences below 1 K. A difference of 0.57 K was recorded for extraction after one heating season (120 days) corresponding to a 2.2 % difference (Cai et al. 2022). Similarly, a 0.37 K temperature difference was recorded after 25 years of extraction (Kolo et al. 2023). The 2014 version of Beier’s model Beier et al. (2014) which was generally intended for shallow BHEs also showed good comparison of \(\Delta T < 0.7 K\) with a DBHE model implemented in OGS (Chen et al. 2019) under matching assumptions. Cai et al. (2022), Wang et al. (2022), and Cai et al. (2022) used an OGS model to further investigate the long-term performance and sustainability of the BHE array system.

-

2.

Cylindrical axisymmetric methods: Since the coaxial DBHE system can be simplified as an axisymmetric problem, many researchers adopted a cylindrical axisymmetric domain to simulate it as listed in Table 1. In order to take into account the effect of groundwater flow, Mottaghy and Dijkshoorn (2012) coupled the finite-difference formulation of cylindrical axisymmetric DBHE to heat and flow transport code SHEMAT. To describe the pipe flow in coaxial DBHE, Bu et al. (2012) included a simple pressure loss equation and quantified the flow resistance of the circulation fluid along the pipes.

-

3.

Full component-discretisation methods: A full 2D or 3D discretisation for the DBHE as well as the surrounding formation is adopted, for example, in Boockmeyer and Bauer (2014) and Doran et al. (2021). Besides, Cai et al. (2019) and Renaud et al. (2019) used fully discretised FVM models in 2D to simulate a DBHE system as listed in Table 1. Fully discretised models have also been used to generate simplified representations of complex heat exchanger configurations with thermally equivalent behaviour in thermal energy storage applications in order to simplify meshing as well as lower the computational cost (Nordbeck et al. 2020).

The first method is particularly attractive due to its computational efficiency compared to fully discretised 3D models but requires special element formulations. When simulating systems from single DBHE to arrays, computational cost of fully discretised models becomes prohibitive. Thus, the trend towards large arrays brings with it a need for special element formulations / dual continuum approaches for the internal heat transfer processes and the coupling to the rock mass. The second method uses cylindrical coordinate system to describe and simulate the DBHE system; every component inside the DBHE borehole can be fully discretised. However, the limitation is that the groundwater effect and DBHE arrays cannot be easily simulated as indicated by Mottaghy and Dijkshoorn (2012). The third method is computationally very expensive for 3D simulations but requires no special implementation and can therefore be set up in any general-purpose code like ANSYS/Fluent (Li et al. 2020), TOUGH2 (Doran et al. 2021) and COMSOL (Hu et al. 2020; Janiszewski et al. 2018; Villa 2020). Besides the DBHE model implemented using the dual-continuum method in OGS (Shao et al. 2016; Hein et al. 2016; Chen et al. 2019, 2021), a fully discretised FEM model developed using OGS was also used by Boockmeyer and Bauer (2014) which allows a direct comparison between both approaches. Other specialised software packages such as FEFLOW (Diersch 2013; Le Lous et al. 2015; Rapantova et al. 2016) also have capabilities for both approaches.

In addition to the single DBHE system, deep arrays have also been studied recently by many researchers (e.g. Welsch et al. (2015); Cai et al. (2021)). Table 1 lists some of the modelling studies in the literature showing different discretisation techniques. Most studies only consider a subsurface model focussing on the heat transfer interaction between the DBHE and the surrounding medium, with occasional consideration given to the effects of groundwater flow. In extended models, the surface (building) component of a Heating, Ventilation and Air-Conditioning (HVAC) unit (e.g. heat pump) can be coupled to the subsurface process models thereby investigating the complete loop of space heating/cooling. An example is the DBHE array coupled with a heat pump model in the study of Cai et al. (2021).

All these studies have mainly relied on a single modelling technique (FEM, FDM, or FVM) to discretise the spatial domain. There are few studies comparing different numerical techniques. For example, Ozudogru et al. (2015) compared FDM and FEM for modelling a shallow U-tube BHE. They indicated that the FDM model has a higher computational efficiency. They also highlighted that whilst FEM can model a heat exchanger with multiple circulation tubes, the FDM model can only work with a single loop. It is to be noted that they used a two-dimensional FDM model comparing it to a three-dimensional FEM model. Moreover, computational time is not listed in many studies, which is an important consideration when evaluating software suitability.

In summary, numerical models are very flexible in simulating a diverse range of operational modes for DBHE systems, including both variable extraction and injection scenarios generating non-trivial temperature distributions or depending on surface installations. Importantly, the assumptions in analytical solutions can be discarded in numerical models. This provides a physically richer simulation, more closely resembling reality. Other features reserved largely for numerical methods include complex property distributions/heterogeneity in the subsurface, settings without any symmetry, state-dependent properties (e.g. equations of state of water), complex flow fields and partial saturation effects. Nevertheless, in order to flexibly simulate full-scale DBHE systems, the computational time of detailed numerical modelling is significantly and unavoidably higher than analytical solutions. One solution to the current trade-off is parallel computation, which is becoming increasingly available.

Semi-analytical

Considering the fast calculation speed of analytical solutions and the flexibility of numerical methods, some researchers have combined analytical solutions with numerical methods to obtain a semi-analytical solution of DBHE systems. For example, Wang et al. (2021) proposed a semi-analytical solution to simulate the DBHE system taking into account the geothermal gradient and validated the solution against OGS numerical simulation results. Previously, Ramey (1962) proposed a semi-analytical solution to quantify the temperature change in wellbores. Zhang et al. (2011) combined the semi-analytical solution of heat flux exchange between wellbores and surrounding formations with the numerical model of the heat transport in formations to improve the simulation efficiency.

Generally, in semi-analytical solutions, because the heat transfer inside and outside the DBHE belong to different domains, their temperature field solution is solved separately. The overall simulation of DBHE can then be performed efficiently by linking water and soil heat transfer through the borehole wall via boundary coupling, which needs to be updated in each time step by the soil heat transfer model. For the heat transfer in the surrounding formation, the heat flux going through the borehole wall can be regarded as the heat source. Thus, within a time step, the borehole wall temperature can be updated, which represents the thermal boundary condition for heat transport in surrounding formations. The iteration between the compartments will continue until reaching the convergence criteria. Based on such methods, Luo et al. (2020) used a semi-analytical solution to evaluate the performance of a DBHE coupled ground source heat pump with non-uniform internal insulation. Gordon et al. (2018) made simplifications of the DBHE, and developed a 1D radial composite cylindrical-source model to calculate the inlet and outlet fluid temperatures. In their model, the vertical fluid temperature distribution is not analysed, and the heat flow from each pipe is assumed to be proportional to the total heat flow and the fluid volume ratio. Whilst semi-analytical solutions combine the advantages of analytical solutions and the flexibility of numerical methods, some assumptions from the analytical solution cannot be avoided, e.g. heat transfer inside the borehole usually adopts steady-state equations for each time step, and the borehole is considered as a cylindrical heat source with finite depth.

Numerical modelling studies

In this section, numerical modelling of closed-loop DBHE systems is discussed for—(i) heat extraction which involves using DBHEs to extract heat from the ground to be used for space heating or other applications (e.g. horticulture); (ii) BTES, in which, through DBHEs, surplus heat is deliberately stored in the subsurface to be re-extracted in periods of high demand (Banks 2012), and (iii) cooling applications, where, the same BTES system used to store heat, is also used for space cooling with particular reference to rejection of heat from the building to the subsurface.

Heat extraction

Modelling has largely been undertaken with the purpose of investigating DBHE heat extraction capacity. The developed models have been used to understand (i) the influence of different engineering and geological parameters (Dijkshoorn et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2019; Renaud et al. 2020; Brown et al. 2021; Brown and Howell 2023; Kolo et al. 2023, 2023); (ii) the varying modes of operation, i.e. constant base load versus intermittent (Cai et al. 2019; Luo et al. 2022; Jiao et al. 2021; Huang et al. 2022; Brown et al. 2023; Perser and Frigaard 2022); (iii) system optimisation (Pan et al. 2020; Gascuel et al. 2022), and (iv) the potential to scale the technology using arrays (Cai et al. 2021, 2022; Zhang et al. 2022a, 2022b). Many studies have arrived at similar conclusions regarding the sensitivity of DBHE performance to these parameters, as described in the following sections.

Impact of geological parameters

Parametric uncertainty has been investigated to understand the implications of geological conditions including rock thermal conductivity, volumetric heat capacity, geothermal gradient, groundwater flow, heterogeneity (i.e. lithological layering) and natural advection in the subsurface.

Generally, an increase in rock thermal conductivity improves the performance of the DBHE by allowing faster thermal recovery of heat in proximity to the borehole (Banks 2012; Brown et al. 2021). Chen et al. (2019) show that for a 2.6 km long DBHE with a mass flow rate of \(0.00833 \hbox {kg}\,\hbox {s}^{-1}\), the outflow temperature can increase by 9.45 K at the end of a 4-month extraction period as thermal conductivity of the surrounding rock is varied from 2 to \(3\,\hbox {W}\,\hbox {m}^{-1}\,\hbox {K}^{-1}\) (Fig. 2). Similar findings have been made by Nalla et al. (2005), Le Lous et al. (2015), Song et al. (2018), and Nian et al. (2019), amongst others, which collectively find a near-linear to logarithmic proportionality between increasing thermal conductivity and increasing DBHE thermal power outputs (at constant mass flow rates) (Brown et al. 2021). Greater rock thermal conductivity also leads to an extended radius of thermal influence around the DBHE (e.g. Kolo et al. (2023); Fig. 3).

Example outflow temperature versus time for a range of thermal conductivities of the subsurface rock (from Chen et al. (2019)). Note that the operation conditions were heat extraction to day 120 (recovery thereafter) with a flow rate of \(0.00833\,\hbox {m}^3/\hbox {s}\) and heat load of 390 kW

When considering the thermal properties of geological media, the thermal diffusivity (rate of heat transfer) is defined by the ratio of thermal conductivity and volumetric heat capacity (the ability of the material to store heat (Banks 2012)). Whilst the thermal conductivity has been well documented in DBHEs, the attention given to the volumetric heat capacity has been less pronounced. The reason for this is likely due to the fact that when operating at a constant base load or inlet temperature, the influence on production temperature is somewhat limited; however, it can impact the thermal recovery of a system which uses intermittent modes of operation (Le Lous et al. 2015). Therefore, in long-term near steady-state operation, the impact of volumetric heat capacity is minor, but when there is cyclic or transient operation, it could be more important as it limits the thermal recovery of the system. This is because the volumetric heat capacity controls the storage of heat or coolth with increased or decreased temperature. It has been shown to be particularly important in thermal energy storage systems (Gehlin 2016).

Example temperature propagation around a DBHE for a range of thermal conductivities of the subsurface rock (adapted from Kolo et al. (2023)). Note that the DBHE was being operated for 6 months at a depth of 6 km, flow rate of \(0.00833\,\hbox {m}^3/\hbox {s}\) and thermal power of 800 kW

Geothermal gradient, or bottom-hole temperature, is directly proportional to the maximum thermal power output (Fang et al. 2018; Brown et al. 2021; Niu et al. 2023). Increased geothermal gradients lead to an increase in available thermal energy, and achievable heat load (Holmberg et al. 2016) and it strongly influences the profitability of any system (Xiao et al. 2023). This is due to there being more available heat in the subsurface which can be mined.

Groundwater flow and natural convection in the porous subsurface media surrounding DBHEs can strongly influence the system; however, the conditions required to impact thermal efficiency are seldom established in reality. Chen et al. (2019) highlighted that groundwater flow from relatively thin aquifers has an extremely minor impact on production of heat from DBHEs. Similar findings were also produced by Le Lous et al. (2015). Others have suggested that Darcy velocities greater than \(1\times 10^{-7}\hbox {m}\,\hbox {s}^{-1}\) can strongly impact the system (Jiao et al. 2022; Brown et al. 2023). The latter study highlighted that at the end of a heating season of 6 months, a Darcy flow velocity of \(1\times 10^{-6}\hbox {m}\,\hbox {s}^{-1}\) in comparison to a conduction only scenario could increase outlet temperature from \(7.84^{\circ }\hbox {C}\) to \(9.04^{\circ }\hbox {C}\) (Fig. 4). This would correspond to an increase in thermal power of 25.2 kW or specific heat extraction rate of about \(27\hbox {W}\,\hbox {m}^{-1}\). Similarly, by modelling natural (free) convection in an aquifer, and the associated variations in groundwater density, Bidarmaghz and Narsilio (2022) report that thermal efficiency (i.e. increase in thermal power output) improved by up to 63 %. The modelled environment simulated Darcy velocities of up to \(8.9\times 10^{-5}\hbox {m}\,\hbox {s}^{-1}\) (Fig. 5). The consensus of modelling results suggest that DBHE thermal performance improves in scenarios of increased groundwater flow and natural convection. The likelihood of encountering such high permeabilities and high Darcy velocities as those reported in Bidarmaghz and Narsilio (2022) and Brown et al. (2023) at depth are unlikely. A Darcy velocity of \(1\times 10^{-7}\hbox {m}\,\hbox {s}^{-1}\) would be encountered where hydraulic conductivities are \(1\times 10^{-5}\hbox {m}\,\hbox {s}^{-1}\) with a hydraulic gradient of 0.01 (1 %) (e.g. Nguyen et al. (2017)). This is unlikely to occur at depth, particularly over large portions of the DBHE, and it is reasonable to conclude that in most systems, groundwater flows will inflict a minor impact on heat extraction. Although in some rare scenarios, such as the Mesozoic Basins across the UK, sandstone thicknesses can reach 2 km and it is possible groundwater could impact DBHE performance under these conditions (Brown 2023).

Example of impact of groundwater flow around a DBHE: a outlet temperature vs time (constant inlet temperature of 5 \(^\circ\)C, flow rate of \(0.005\,\hbox {m}^3/\hbox {s}\), rock thermal conductivity of 2.55 W/(mK)); b inlet (dashed lines) and outlet (solid lines) temperatures against depth; c thermal propagation around the DBHE, and d cross-slice through thermal plume at 500 m depth (from Brown et al. (2023))

Darcy velocity through a 5 km deep model with varying aquifer properties highlighting free convection (adapted from Bidarmaghz and Narsilio (2022)). Note: DBHE is the coaxial borehole heat exchanger, Vw is Darcy velocity and k is permeability

Another important aspect of the subsurface geology is the method of modelling the rock itself (i.e. homogeneous or heterogeneous strata). Many studies consider a homogeneous geology with constant thermal and hydraulic properties (e.g. Liu et al. (2019); Brown et al. (2021); Piipponen et al. (2022)). Others model depth-dependent thermal properties (e.g. Hu et al. (2020, 2021)), whilst some consider lithological layering (e.g. Liu et al. (2020); Doran et al. (2021); Gascuel et al. (2022); Kolo et al. (2022, 2023)).

Despite improving the geological representation of the model, the addition of lithological layering only produced a minor difference in outlet temperature of \(< 1^{\circ }\hbox {C}\) in comparison to the homogeneous model equivalent for a variety of depths (Kolo et al. 2023). The discrepancy was found to increase with depth due to the additional vertical lithological variations. It is also worth noting that whilst many have investigated lithological layering, few, if any, have considered realistic geological features or facies modelling which are typically incorporated into reservoir modelling in conventional geothermal systems (e.g. Crooijmans et al. (2016); Wang et al. (2021); Major et al. (2023)) or petroleum applications (e.g. Abdelmaksoud et al. (2019); Mitten et al. (2020)) and impact the hydraulic/thermal subsurface characteristics. It is difficult to quantify the impact such systems could have on the performance of a DBHE; however, it is likely in highly heterogeneous systems which could correspond to variable thermal properties, degree of fluid saturation or groundwater flow would be most influential on results.

Constant thermal properties (rather than those varying with temperature and time) appear to produce reasonable estimates to real data obtained from sites (Cai et al. 2019, 2021). Yet, it has been suggested that temperature-dependent properties can in some cases increase the outlet temperature by \(1^{\circ }\hbox {C}\) or c. 11 % relative deviation for a DBHE of 3500 m depth (Hu et al. 2020). When comparing models which include constant properties against those using temperature-dependent properties, such as OGS (homogeneous) against T2Well-EOS1/TOUGH2, the discrepancy for a 922 m well was \(<0.6^{\circ }\hbox {C}\) (Brown et al. 2023). Comparing this result to the findings of Hu et al. (2020) could imply that depth amplifies any influence of temperature-dependent properties. Similarly, higher temperature systems also exhibit naturally greater influence of temperature-dependent properties (Doran et al. 2021). Therefore systems that encounter a wider range of temperatures may require temperature-dependent modelling of properties.

Impact of engineering parameters

Parametric studies have been conducted to investigate the variations in engineering conditions, including: (i) operational mass flow rates; (ii) borehole and pipe structural design; and (iii) material thermal conductivity and insulation. These characteristics will impact both thermal (e.g. Abdelhafiz et al. (2023)) and hydraulic performance (e.g. Morchio and Fossa (2019)).

One of the most important parameters for determining the thermal drawdown in a DBHE, the outlet temperature and thermal power, is the mass flow rate within the system. This is not primarily because high flow rates lead to greater heat production from the formation, but because they minimise the contact time between upward and downward flow streams and thus minimise internal thermal “short-circuiting” in the borehole. Assuming an insulated central pipe, lower flow rates result in higher outlet temperatures, but correspond to lower thermal powers (Toth et al. 2018; Doran et al. 2021; Guo et al. 2023). When considering the thermal power, performance of the system and net energy, all of these parameters will have optimal values dependent on the flow rate. Kolo et al. (2023) highlighted that increasing flow rates leads to an increase in thermal power extraction, but also an increase in pressure drop. Increased energy expenditure in the circulation pump results in lower net energy production and lower coefficients of performance (Brown et al. 2021; Gascuel et al. 2022; Kolo et al. 2023). A trade-off exists for mass flow rate between pressure drop and maximum thermal power output. This was highlighted by Brown et al. (2024), who highlighted that optimal conditions could be achieved to minimise the parasitic losses whilst maximising the thermal output as a function of engineering parameters.

In combination with the operational flow rate of the DBHE, the geometrical design of the borehole and coaxial pipe design will have important consequences for system pressure drop and heat transfer. Larger borehole radii allow a greater thermal performance by generating slower downward velocities in the annular space, larger contact area around the DBHE and greater heat extraction from the formation (Li et al. 2021; Wang et al. 2022). Similarly, a narrower central pipe leads to higher production temperatures and thermal powers, as the heat transfer area between central pipe and annulus is reduced (Brown 2020). Whilst larger boreholes are preferable, drilling costs may increase as a result. Additionally, many studies have focussed on repurposing oil and gas wells (e.g. Sapinska-Sliwa et al. (2016); Westaway (2016); Hu et al. (2020); Gascuel et al. (2022); Gizzi et al. (2021); Brown and Howell (2023); Santos et al. (2022); Guo et al. (2023)) or geothermal exploration wells (e.g. Renaud et al. (2019); Kolo et al. (2022, 2023); Brown et al. (2023, 2023, 2023); Noorollahi et al. (2016)) and are constrained to a pre-existing narrow diameter borehole. Depth also influences thermal performance as it leads to higher outlet temperatures, thermal power and specific heat extraction rate (e.g.Piipponen et al. (2022); Deng et al. (2020)). Whilst it is useful to increase the depth, it will also result in greater pressure losses and hence a decline in system efficiency (Brown et al. 2021).

Closed-loop geothermal systems have lower extraction rates than open-loop systems due to low heat transfer rates between the subsurface and the limited surface/contact area (Beckers et al. 2022). In addition to targeting high-temperature resources, the slow heat transfer rates can be addressed by (i) increasing the DBHE contact area with the rock and (ii) increasing turbulence in the DBHE flow, although this can lead to increased parasitic losses (Brown et al. 2024). To achieve the former, coaxial DBHEs can be augmented with a long horizontal section (Guo et al. 2023) (see Fig. 6). Wang et al. (2021) conclude that a 2000 m horizontal section increases the outlet temperature by a margin of around 20 K (0.96 MW thermal power). Introducing lateral sections will inevitably also come with drilling complexities and cost (Beckers et al. 2022). The second method to enhance heat transfer, by increasing internal DBHE turbulence, has been explored through the modelling of vortex generators (Sun et al. 2022) (Fig. 7). The addition to pipe design was found to successfully increase overall heat output but simultaneously increased the pressure drop within the DBHE, thereby increasing parasitic losses from the circulation pump. Whilst the discretisation method in the study was not stated, future modelling of DBHEs with vortex generators can vary in modelling approach. They can apply either full computational fluid dynamics models to more accurately represent key processes, or alternatively, the thermal resistance of the casing string could be modified to represent the increased turbulence.

Schematic diagram of a DBHE with horizontal extension. Tubing indicates the central outlet pipe. (from Sun et al. (2019))

Distributions of turbulent kinetic energy (from Sun et al. (2022)). Note that ST is smooth tube, BVG is a bump vortex generator, IVG is an impeller vortex generator and TVG is a thread vortex generator

The influence of grout or cement properties is generally regarded as minimal to moderate impact for lower temperature systems (e.g. Le Lous et al. (2015); Brown et al. (2023)), with an increase in thermal conductivity resulting in an increase in thermal power. A continuous increase of the grout thermal conductivity does not continuously improve the production fluid temperature, but can enhance the transmission of heat; however, this impact does appear to decline with operational time (Huang et al. 2020). In higher temperature systems, it would appear that variations in thermal conductivity of the grout can impact results more strongly (e.g. Doran et al. (2021)). Some researchers have also gone further to investigate enhanced thermal conductivity zones using a soilcrete zone created through jet grouting, enhancing the thermal power by 1.27 times in contrast to normal grout (Yu et al. 2021). However, Yu et al. (2021) conclude that the length/radius of the zone are more important than its thermal conductivity considering typical ranges. Some studies have considered insulation of the DBHE casing and inner pipe. The insulation of casing at the top of the borehole typically has a minor or negative impact on the thermal performance (Hu et al. 2020; Fang et al. 2018), but insulation of the central pipe improves performance (Hu et al. 2020) as it mitigates thermal short-circuiting. Lower thermal conductivity materials of the central pipe such as high-density polyethylene or vacuum insulating tubing have the potential to significantly improve performance, but can require higher investments and installation costs (Śliwa et al. 2017, 2018). Thermal performance also increases as the thickness of the insulation layer increases (Guo et al. 2023).

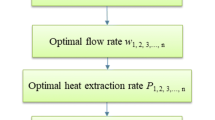

Optimisation of the aforementioned engineering parameters can help improve performance, particularly when focusing on varied flow rates to meet variable heating load demands throughout the heating season. Wang et al. (2022) used a mathematical optimisation procedure that utilised a convex function and interior-point method to find the minimum total power consumption; this allowed overall energy savings. Further optimisation studies have been performed by Pan et al. (2020) on both engineering and geological parameters using a method based on the lowest Average Energy Cost index which allows a reduction of up to 22.1 % in power consumption. Similarly, optimal parametric studies can also help to identify key parameters that influence thermal and hydraulic performance (e.g. Brown et al. (2021); Gascuel et al. (2022); Jia et al. (2022)).

Impact of deep borehole heat exchanger arrays

Scalability at a single site can be achieved by increasing the number of DBHEs to establish a greater thermal power output (i.e. Fig. 8). In designing such a system, the lateral spacing of DBHEs and shape of the array must be considered to minimise negative thermal interference (Cai et al. 2022). Optimal inter-borehole spacing is likely to vary depending on the local geology and method of operation, although modelling has demonstrated that line arrays may have better performance than square arrays for heat extraction due to reduced thermal interference (Brown et al. 2023). Larger spacing for arrays results in reduced thermal interference and thus, higher outlet temperatures (Fig. 9). DBHE arrays are impacted by similar parameters as are single DBHEs (Zhang et al. 2022b). Unlike single DBHEs, arrays can operate in parallel by incorporating a merger and splitter to apply a heat load across the array, rather than individually to each DBHE (e.g. Cai et al. (2021)).

Schematic of a DBHE array (from Brown et al. (2023))

Temperature profiles through the ground for different line arrays: a 20 m spacing; b 30 m spacing; c 40 m spacing; d 50 m spacing. Profiles taken directly through the line array (from Brown et al. (2023))

Impact of boundary conditions

Finally, the influence of boundary conditions has been evaluated for heat extraction performance, e.g. Ma et al. (2023) and Jiashu et al. (2022). Jiashu et al. (2022) performed a comparative study of (i) constant inlet water temperature; (ii) constant fixed power boundary condition, and (iii) constant wellbore temperature. They concluded that the constant temperature boundary conditions and constant wellbore temperature provide similar results. They also suggest that the constant heat output, or power boundary condition are less likely to be implemented in practice. This seems unusual considering that many shallow closed-loop systems operate using a power boundary condition since they are coupled to a heat pump and building load. Further research is required to explore this uncertainty. By considering Neumann no flow and Dirichlet constant temperature boundary conditions, Kolo et al. (2022) found that the choice of boundary conditions at the upper surface of the model domain has minimal impact on fluid inlet and outlet temperatures. This is plausible considering that surface temperature fluctuations typically only affect depths shallower than 10 m (e.g. Al-Khoury et al. (2010)), thus significantly small compared to the DBHE length.

Thermal energy storage

By exploiting sources from curtailed wind power (Brown et al. 2023) to rooftop solar thermal (Sibbitt et al. 2007, 2012; Kolo et al. 2023) to waste heat (Mahon et al. 2022; Guo and Yang 2021), seasonal thermal energy storage (STES) supports the security of supply in multi-vector low-carbon heating and cooling solutions in strongly seasonal climates (BEIS 2016; Gluyas et al. 2020; Kallesøe et al. 2020; Xu et al. 2014; Lyden et al. 2022). Underground thermal energy storage (UTES) is a subset of the wider branch of heat storage technologies (Nagel et al. 2016). Loosely segregated amongst pit, tank, mine, aquifer and borehole storage; offering an array of installed benefits and costs (BEIS 2016) but all assist in addressing the temporal mismatch in supply and demand of heating and cooling availability from low-carbon sources. The review herein is primarily concerned with the use of DBHEs in closed-loop deep BTES (DBTES; Fig. 10).

Much can be learnt from the experience with shallow BTES systems and applied to the deeper context. Reviews from Skarphagen et al. (2019) and Gao et al. (2015), for example, offer exemplary overviews of the key literature on shallow BTES. These reviews, amongst others, describe the fundamental operating and design considerations, many of which are applicable to both shallow and deep BTES contexts, with the notable exception that deeper systems favour a coaxial DBHE over the U-tube alternative (e.g. Brown et al. (2024)).

Both shallow and deep BTES operate with the same basic charging and discharging principles: by injecting warm fluid into a single BHE or BHE array, BTES systems transfer heat to the cooler insulating subsurface media (charging), and by subsequently reversing the flow direction and injecting cold fluid into the BHE(s), extract heat from the thermal plume proximal to the borehole residing from the prior charging phase(s) (discharging). If no prior charging is present, then the operation of mining the heat-in-place is termed extraction. The choice of when to charge, discharge or extract is dependent on the application demand and the availability of alternative sources at each time step of the BTES control.

During charging, the thermal plume expands and the charging power (rate of heat transfer) typically reduces as the system approaches a steady-state equilibrium between the BHE and surroundings. Typically, in systems with large differences in fluid injection temperature and surrounding formations, an initial “start-up, or pre-charge” period is maintained, during which the majority of the annual operating cycle is spent charging the thermal store (Skarphagen et al. 2019). This initial start-up may take several annual cycles to bring the BHE into a pseudo-steady state with the surrounding media; however, once complete the start-up procedure assists in improving the system’s storage efficiency (Skarphagen et al. 2019). Cyclic charging and discharging operations should be initiated once the initial start-up period, if necessary, is complete.

Borehole thermal energy storage array with sources and end-users (adapted from Homuth et al. (2013) and Welsch et al. (2018)). Characterised by slow (seasonal) thermal responses, and hence suitable as STES systems, DBTES can be coupled with dynamic thermal energy storage (buffer tank) at the surface level to act as “thermal capacitors”—establishing a comprehensive thermal store used to meet both diurnal and seasonal fluctuations of demand

The thermal losses are incurred during the annual cycling of charging and discharging from the BTES. These losses are a function of several design and operational parameters, including, but not limited to, inlet temperature of the working fluid; local geothermal gradient; DBHE geometrical design configuration; material properties of the DBHE and surrounding formation; borehole spacing in the array, and shape factor (surface area to volume ratio in an array) (Skarphagen et al. 2019) (Fig. 11). Thermal energy recovery can be maximised by tailoring these system parameters. For example, borehole arrays aim to minimise the shape factor of a BTES system—hexagonal or cylindrical arrays being favoured over a single row of BHEs or standalone BHE—thus reducing thermal losses to the surrounding formations and enabling constructive thermal interference between neighbouring BHEs (Skarphagen et al. 2019; Lanini et al. 2014). A preference for dense arrays in storage systems is in stark contrast to the extraction-only DBHE case which aims to avoid or minimise interactions across thermal drawdown effects. The optimal array configuration and DBHE design is distinctly use-case dependent. Despite the important role of shape factor in BTES storage arrays, ongoing work has investigated the potential to reduce the number of boreholes in an array (increasing the ratio of surface area to volume ratio) in favour of borehole depth, resulting in single borehole or sparse arrays DBTES systems, e.g. Welsch et al. (2015, 2016); Schulte et al. (2016).

At the heart of the switch from shallow arrays to deep (typically more sparse) arrays is the stringency of regulatory bodies to minimise the environmental impact of heat storage, particularly high-temperature storage (\(T>35^{\circ }\hbox {C}\)), on shallow groundwater resources (e.g. Gao et al. (2015); Tsagarakis et al. (2020); Hähnlein et al. (2013)). Examples of the environmental impacts of heat storage in the shallow subsurface have been documented by Bonte et al. (2011) and Mielke et al. (2014), amongst others. To mitigate the risks posed to groundwater assigned for other purposes such as drinking water or irrigation, Homuth et al. (2013) propose the targeting of deeper geological formations whilst insulating the shallow section of the BHE. This minimises the interference of thermal plumes in the shallow subsurface. Although this switch to deeper sparse arrays has a detrimental effect on the surface area to volume ratio, advantages to DBTES adoption include: (i) reduced surface footprint requirements, potentially improving the feasibility of installing BTES systems in densely populated areas with existing infrastructure and (ii) higher temperature sources—such as Variable Renewable Energy (VRE) and Combined Heat and Power—can be integrated than is currently permissible in shallow BTES systems, thus improving heat pump COPs in the case of high demand-side temperatures (Homuth et al. 2013; Welsch et al. 2018; Gao et al. 2015; Malmberg 2017).

One must consider the metrics used when assessing DBTES performance and ensure consistency amongst metrics when drawing comparisons across systems. The issue of selecting performance metrics is particularly prominent in the DBTES literature, which suffers from ambiguity regarding the measurement of “storage efficiency.” Although efficiency estimates are impacted by both operational and design parameters, the different choice of metrics makes comparison of published values challenging. For example, using different metrics, Welsch et al. (2016) and Brown et al. (2023) report thermal storage efficiency values of 83 % and 1 %, respectively, whilst other estimates lie within this range (e.g. Schulte et al. (2016) and Fu et al. (2023)). There is therefore a clear need to clarify the “efficiency” measure being reported. The following list (Eqs. 15–20) attempts to define common approaches to this performance metric and provides some suggested terminology needed to bring consistency to DBTES comparison. With the exception of the ‘heat storage yield ratio’, the metrics described below are typically expressed on a per-annum basis. The variables used in the storage efficiency metrics are shown in Fig. 12 and defined in Table 2.

-

1.

Thermal recovery factor (TRF): ratio of total heat extracted during discharging period to total heat injected into surrounding formations during charging period (Welsch et al. 2016; Hellstrom 1992; Seib et al. 2022; Bär et al. 2015b; Schulte et al. 2016):

$$\begin{aligned} \text {TRF}= \frac{Q_\text {discharge}}{Q_\text {S}} \end{aligned}$$(15) -

2.

Thermal storage efficiency (TSE): ratio of difference in total energy extracted with and without a storage charging period to total energy injected to surrounding formations during charging period (Brown et al. 2023, 2023):

$$\begin{aligned} \text {TSE}= \frac{Q_\text {gain}}{Q_\text {S}} \end{aligned}$$(16) -

3.

Thermal charging efficiency (TCE): ratio of total energy injected to surrounding formations during charging period to the total energy inputted at the wellhead during charging period (Xie et al. 2018):

$$\begin{aligned} \text {TCE}= \frac{Q_\text {S}}{Q_\text {in,charge}} \end{aligned}$$(17) -

4.

Thermal recovery advantage (TRA): ratio of difference in total annual energy extracted with and without charging to total energy extracted in the case without charging (Skarphagen et al. 2019; Fu et al. 2023). Also referred to as heat extraction improvement rate (HEIR) in Fu et al. (2023):

$$\begin{aligned} \text {TRA}= \frac{Q_\text {gain}}{Q_\text {ex}} \end{aligned}$$(18) -

5.

Thermal accumulation efficiency (TAE): the ratio of annual accumulation of heat stored in the BTES system to the amount of heat injected during the charging period (Skarphagen et al. 2019):

$$\begin{aligned} \text {TAE}= \frac{Q_\text {S} - Q_\text {discharge}}{Q_\text {in,charge}} \end{aligned}$$(19) -

6.

Heat storage yield ratio (HSYR): ratio of the net energy gain in the entire service life to the electrical power consumed by the heat storage operations (Fu et al. 2023):

$$\begin{aligned} \text {HSYR}= \frac{Q_\text {gain} - W_\text {P}}{W_\text {P}} \end{aligned}$$(20)

Deep borehole thermal storage arrays

Modelling of DBTES arrays (Table 3) have been significantly informed by the ongoing work in Darmstadt, Germany and the resulting project “Seasonal Crystalline Medium Deep Borehole Thermal Energy Storage” (abbreviated to SKEWS; (Homuth et al. 2013; Bär et al. 2015a, b; Seib et al. 2022, 2022, 2024). Bär et al. (2015a) and Bär et al. (2015b) expand upon work by Homuth et al. (2013) using numerical modelling in FEFLOW to assess the initial capacity and sustainability of heat storage scenarios in the hydrogeological context of the Darmstadt site. Initial results showed that shallow BHE arrays (19 BHEs at 105 m) exhibited an annual TRF (Eq. 15) of approximately 10 % after year one of operation which tended to 25 % after 30 years due to annual thermal accumulation (Bär et al. 2015a). In contrast, DBHEs with similar total drilled lengths (4 BHEs at 500 m depth) settled at just c. 15 % at year 30 despite starting at a comparable TRF in year one (c. 10 %). This difference in TRF improvement over the BTES lifespan is likely a consequence of the change in shape factor, from dense to sparse arrays, and suggests, assuming drilling costs increase exponentially with depth (Tester et al. 2005; Banks 2023), that shallower BTES arrays will yield a cheaper storage option per kWh. The tendency to form steady-state annual TRFs at year 30 arises from the movement towards thermal equilibrium between the circulating fluid and surrounding formations. This represents a steady decrease in thermal charging capacity and annual TAE (Equation (19)) over the BTES lifespan, as also reported in Skarphagen et al. (2019).

It should be noted that the BTES arrays studied in these models are connected in parallel. The BHEs of the array can also be linked in a combination of serial and parallel connections, with heat extraction occurring in the outer BHEs first and moving progressively towards the centre during the discharging period; meanwhile, injection occurs in the central BHEs first (the core of the array) and works radially outward during charging (Skarphagen et al. 2019). The advantage gained from this additional operational control may be partially mitigated by the resulting increase in hydraulic head, particularly as BHE depth increases (Skarphagen et al. 2019). Nonetheless, configurations in the literature discussed herein modelled BHEs in parallel unless stated otherwise.

Given the significant role of drilling on DBTES installation costs (operational costs being relatively low in comparison), Schulte et al. (2016) attempt to minimise the total drilled borehole length of BHEs in DBTES arrays, subject to constraint on meeting the annual heat demand and maintaining BHE depths beyond 200 m as a fictitious legal requirement. To achieve this, a surrogate model was initially trained on numerical models in MATLAB using 63 different BTES arrays (benchmarked against FEFLOW simulations) to explore the search space of possible array configurations whilst avoiding the computational burden of full numerical models. The proxy model was applied in a genetic algorithm, to identify the global optimum of BHE length and array size. In agreement with the findings of Bär et al. (2015a), the authors observe that TRF favours a larger number of shallow BHEs over a sparse array of DBHEs for the same total drilled length and find an array of 7 BHEs at 220 m depth offered an optimal solution under the imposed constraints. This solution, generated by the surrogate model and validated with a pre-existing MATLAB numerical model, operated at a TRF of 41 %, and reinforces the notion that sparse DBTES arrays are susceptible to greater thermal losses. Schulte et al. (2016) highlight the increasing inaccuracy of the proxy model towards the edge of the multi-dimensional parameter space as the training data become more sparse, bringing potential implications for the outputs generated for deeper BHE models in the genetic algorithm.

In assessing the impact of BTES parameters on system performance, Welsch et al. (2016) used a One-at-a-Time or local sensitivity analysis to compare 250 storage models implemented in FEFLOW. Variable parameters included borehole array layout (number of BHEs, BHE depth—100 to 1000 m—and spacing), fluid inlet temperatures and host rock thermal and hydraulic properties. The analysis indicates that stored heat, extracted heat and annual TRF values all increase with BHE length and number of BHEs in the BTES array (agreeing with the findings of Schulte et al. (2016)). The important role of the array shape factor (surface area to volume ratio) is again demonstrated by the positive short-term impact (years 1–3) on TRF values observed for circular array configurations. At year 30 of the simplified operating scheme considered, annual TRF values were found to range from 32 % (7 BHEs at 100 m depth) to 83 % (37 BHEs at 1000 m depth), up from approximately 25 % and 45 % in year 1, respectively. These estimates demonstrated a significant increase from Bär et al. (2015a, 2015b), highlighting the improved TRF values that can be achieved by DBTES over shallow systems for high inlet temperatures (in this case \(90^{\circ }\hbox {C}\)). The TRF values were also found to increase as the ratio of charging to discharging inlet temperatures increased, whereas increases in rock thermal conductivity and groundwater flow velocity are found to negatively impact TRF values (e.g. a rock hydraulic conductivity increase from \(1\times 10^{-7}\hbox {m}\,\hbox {s}^{-1}\) to \(1\times 10^{-5}\hbox {m}\,\hbox {s}^{-1}\) constitutes a drop in TRF from c.67\(\,\% \,\text {to}\, c.30\) % due to advective losses from groundwater flow). The impact of rock volumetric heat capacity is reportedly negligible to weakly positive. Finally, whilst Welsch et al. (2016) used a local sensitivity analysis to reduce computational costs, the interdependency between the variables in the model must be acknowledged. Potential compounding or conflicting effects on storage efficiency, storage capacity and extraction capacity indicate the need for global sensitivity analyses or experimental design in future modelling of DBTES systems.

Using a synthetic district heating network case study, Welsch et al. (2018) carried out an environmental and economic life cycle assessment to identify Pareto optimal solutions to energy system design, using levelised cost of heat (LCOH) and global warming potential as performance metrics. The study found that incorporating DBTES into a hybrid combined heat and power-solar thermal collector gave the most efficient Pareto optimal design heating system (minimisation of financial and economic costs) across all those considered. This result was observed for the “business-as-usual ” case (constant electricity grid carbon intensity) without subsidies as well as the “evolution” case (forecasts a reduction of electricity grid carbon intensity) both with and without subsidies. This optimisation arises from the system becoming self-sufficient in the supply of power from the combined heat and power to operate the DBTES circulation pump, heat pump, and solar thermal collector. Welsch et al. (2018) conclude that when compared against the business as usual and evolution cases, the hybrid combined heat and power-solar thermal collector system produces a reduction in global warming potential by 54 % and 29 %, respectively.

As part of project SKEWS, Seib et al. (2022) investigated the impact of fault zone hydraulic conductivity and thickness on storage performance. Using a FEFLOW model of the case study area, the authors report just a 2.1 % variation in TRF values for the final BTES system proposal (750 m deep in a 37-BHE hexagonal array, see Fig. 11(b)) across all hydraulic conductivity and fault zone thickness parameters tested: ranging from 69.6 % at a 4 m fault zone thickness with a hydraulic conductivity of \(1\times 10^{-3}\hbox {m}\,\hbox {s}^{-1}\) to 71.7 % at 0.5 m, 1 m, 2 m fault zone thicknesses and hydraulic conductivity of \(1\times 10^{-5}\hbox {m}\,\hbox {s}^{-1}\). Consequently, the storage capacity and TRF are found to decrease with transmissivity, as the rate of increase in heat injection capacity is less than the rate of decline in heat extraction capacity. Details of the SKEWS project are discussed further in "Example of deep BTES project – Darmstadt (SKEWS)" section.

Deep single-well borehole thermal energy storage

Several attempts have been made to move beyond conventional thinking on BTES system design as arrays (Lanini et al. 2014; Skarphagen et al. 2019) (Fig. 11), and have extended the field to consider the technical feasibility of single-well DBTES systems (Westaway 2016; Brown et al. 2023, 2023; Xie et al. 2018; Fu et al. 2023) (Table 3). This is typically seen as a means for repurposing abandoned onshore hydrocarbon wells or geothermal exploration boreholes. The cost of drilling—which has been shown to make DBTES expensive in comparison to shallow BTES arrays (Bär et al. 2015a; Schulte et al. 2016)—is mitigated in such scenarios and is claimed to justify the adverse effect to shape factor (surface-area to volume) experienced in repurposed single wells.

Westaway (2016), using an analytical BTES model, estimated that the 2 km lateral section of a single shale gas well (Fig. 13) has the potential to sustainably store \(1.6\,\hbox {GWh}_{\textrm{th}}\) at a peak specific energy storage rate of \(300\hbox {W}\,\hbox {m}^{-1}\) (or \(0.6\,\hbox {MW}_{\textrm{th}}\)). These findings neglect heat transfer in the vertical length of the borehole, but nonetheless provide possible orders of magnitude in storage. Advanced economic evaluation is needed, including considerations of the increased difficulty of installing coaxial BHE components within a heavily deviated deep borehole (Sun et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2021).

Abandoned geothermal boreholes also offer the possibility for repurposing. For example, the Newcastle Science Central Deep Geothermal Borehole (NSCDGB) in north-east England—drilled originally as a conventional geothermal exploration well—encountered unexpectedly low permeability in the targeted Carboniferous Fell Sandstone formation at depths beyond 1400 m. This led to the abortion of a planned open-loop geothermal system in the area (Younger et al. 2016). The NSCDGB has subsequently been assessed for its DBHE heat extraction potential in Kolo et al. (2022, 2023) and recently these modelling efforts have been extended to explore the site’s feasibility for a single-well DBTES system (Brown et al. 2023, 2023). A sensitivity analysis of DBTES performance for the top 920 m of single-well design was carried out using an inhouse dual-continuum numerical model developed in MATLAB (benchmarked against OpenGeoSys) (Brown 2020; Brown et al. 2021). A \(95^{\circ }\hbox {C}\) constant inlet temperature (stored total of 1.23 GWh) resulted in a minimum increase of 15 kW in heat extraction from the DBTES, up 28% in comparison to the no-storage case by the end of a hypothetical 6-month charge–discharge cycle. Brown et al. (2023) used Spearman’s and Pearson’s correlation coefficients to assess the global sensitivity of stochastically-generated parameter values on thermal storage efficiency (TSE and TCE, Eqs. 16 and 17, respectively). It should be noted that these metrics would be difficult to apply in reality as they rely on comparing the energy extracted from the DBTES with and without the presence of a storage charging period. The low TSE and TCE values observed (\(<20\) %) for many of the parametric input spaces led the authors to conclude that single-well DBTES systems are unlikely to outperform shallow BTES arrays in most operating environments. The sensitivity analysis also found TRF to be most sensitive to changes in the undisturbed geothermal gradient, flow rate, and inlet fluid temperatures during charge and discharge phases. These findings are largely in agreement with those of Xie et al. (2018), who, using a semi-analytical model, likewise carried out sensitivity analysis of repurposed abandoned hydrocarbon wells and found inlet temperature to have the largest influence on TCE. Xie et al. (2018) subsequently presented an approach to optimise well depth for a given heat source temperature (BTES fluid injection temperature during charging) in order to maximise the TCE of the system (Eq. 17).