Abstract

Background

Adapting to child-rearing is affected by multiple factors, including environmental and individual factors. Previous studies have reported the effect of a single factor on childcare maladjustment; however, to prevent maladaptation in and to support child-rearing, a comprehensive evaluation of factors is necessary. Therefore, this study developed a comprehensive assessment tool for childcare adaptation.

Methods

We conducted semi-structured interviews with specialists whose jobs entailed supporting parents. Items were extracted from the interview data and used to develop a new questionnaire. Mothers with a child aged 0–3 years completed the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology as a depression index. We performed both factor and correlation analyses on the collected, data and multiple regression analyses to determine which factors predict depressive tendencies leading to childcare maladaptation. Subsequently, an assessment algorithm model was built.

Results

1,031 mothers responded to the questionnaire which had 118 items in five domains. A factor analysis was performed on each domain to develop the Comprehensive Scale for Parenting Resilience and Adaptation (CPRA). The CPRA comprised 21 factors and 81 items in five subcategories: Child’s Temperament and Health (1 factor, 5 items); Environmental Resources (5 factors, 20 items), Perceived Support (4 factors, 15 items); Mother’s Cognitive and Behavioural Characteristics (6 factors, 22 items), and Psychological Adaptation to Parenting (5 factors, 19 items). Correlations between all factors and depressive symptoms were identified. Depressive symptoms were predicted by factors from four subcategories: Environmental Resources, Perceived Support, Mother’s Cognitive and Behavioural Characteristics, and Psychological Adaptation to Parenting. A comprehensive model of mothers’ psychological adjustment was developed using the CPRA’s domain structure.

Conclusions

The CPRA enables researchers to understand the strengths and weaknesses of mothers. Mother’s maladaptive states can potentially be predicted by understanding the interactions between these multiple factors. The developed model can provide the necessary support to mothers and increase mothers’—and others’—awareness of the support that can prevent childcare maladjustment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mothers’ mental and physical health has a significant impact on child-rearing behaviour and affects the development of their children. Pregnancy and childbirth can be both physical and psychological stressors for mothers [1, 2]. Therefore, it is necessary to establish appropriate support for mothers, particularly mothers who struggle with child-rearing; various efforts are being made to provide support [3,4,5]. Predicting maladaptation to child-rearing, preventing maladaptation, and preparing the necessary resources that can be shared during prenatal check-ups can help ensure the appropriate support for mothers. Most often, support and intervention for mothers have been provided based on the experience of clinicians, such as doctors, midwives, nurses, public health nurses, and clinical psychologists. By observing the condition of both the mother and the child and communicating with the mother, these clinicians assess the traits and development of the mother and child and may discern struggles or challenging situations. When support is deemed necessary, intervention and support measures—customised according to the needs of each mother caring for her baby—can be offered. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Self-Evaluation Scale (EPDS) has been used to identify mothers who need early support [6]. However, this scale addresses only depression, and limited information is available that can be used to develop interventions for anxiety and other difficulties. Other limitations to the EPDS have also been highlighted [7, 8].

Previous studies of maladjustment to child-rearing have focused on individual factors, such as family support [9,10,11], mothers’ fatigue and characteristics, disabilities [12, 13], and child development. However, few studies have comprehensively and quantitatively examined environmental factors and factors related to the child, rather than focusing on maternal development and personality traits as predictors of early child-rearing maladjustment. Assessing mothers’ personality/developmental factors and environmental factors around childbirth can promote maternal self-care and prepare support coordination by supporters. Baraitser and Noacl [14] defined maternal resilience as the capacity for mothers to survive the vicissitudes of the parenting experience itself and stated it has received little attention. An existing measure of childcare resilience in Japan is the Childcare-Related Resilience Scale by Miyano et al. [15]. As this scale consists of three factors, "I am", "I have" and "I can", which were identified as components of resilience by Grotberg [16] and Heiw [17], it does not include the developmental characteristics of mothers and the nature of the children they are raising. Therefore, this study developed the Comprehensive Scale for Parenting Resilience and Adaptation (CPRA). CPRA can be utilised to comprehensively assess maternal developmental/personality traits and environmental factors related to parenting maladjustment. To develop the scale, predictive factors for childcare maladjustment were extracted from previous research reviews and interviews with clinicians. Using the extracted items, a quantitative survey was conducted involving mothers raising children. We present a structured model of developmental/personal traits and environmental factors that predict mothers’ maladaptation to childcare.

Methods

Participants

Participants were mothers raising a child aged 0–3 years old and who live in Japan. The sample size was set at 1200, based on the guidelines for the number of items included in the multivariate analyses—118 items × 10 [18]. The survey was distributed to 4800 people who met the sample conditions set by the research company INTAGE Inc., and 1031 valid responses from participants who provided informed consent were included in the final analyses (response rate of 21.5%). Sampling was performed so that the questionnaire would be distributed in urban and rural areas of Japan.

Survey period: October 2019.

Procedure

The survey was conducted as a web survey. An original questionnaire was developed, and a cross-sectional study was conducted to assess the psychological adjustment of each mother. The questionnaire comprised 138 items, including 4 face items. Of these, 118 questions were original to the study’s questionnaire, and 16 items were from the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS). The completion time was approximately 30 min. On the face sheet, we asked about socio-demographic characteristics, such as age, history of pregnancy and childbirth, child’s age, employment, family stressors, and household structure. Next, mothers were asked to answer 118 questions that were created based on the results of interviews with specialists in child-rearing support to measure the factors related to the difficulty of raising children. Each item was rated on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

In creating questionnaire items for inclusion, we first examined factors from previous studies that had been found to affect feelings associated with difficulties raising children. It became clear that the primary factor categories were environment, children, and personality. Next, an interview survey was conducted with four experienced specialists (one liaison nurse, one clinical psychologist, and two social workers) involved in childcare support at obstetrics and gynaecology and childcare support centres. In the interview, each specialist was asked to explain in detail the characteristics of cases encountered in the clinical setting that demonstrated a need for support. Interview data were used in exploratory content analysis. From this analysis, as many question items as possible, that could broadly cover the study’s research focus were created. Three researchers examined the appropriateness of these potential questions, grouping them according to the primary factor categories identified from previous research. Items were reduced to a number that could be answered reasonably, and the wording and ease of answering were confirmed by researchers. A questionnaire was created that consisted of 118 items in 5 domains: Child’s Temperament and Health, Environmental Resources, Perceived Support, Mother’s Cognitive and Behavioural Characteristics, and Psychological Adaptation to Parenting. In order to establish appropriate support for mothers struggling with childcare, the Japanese version of the QIDS (QIDS-J) [19] was used as an index for the mental maladjustment of the mothers, rather than resilience or adjustment scales. The QIDS is commonly used as a clinical outcome measure. Although it would have been best to examine the concurrent validity of the CPRA with the EPDS, due to a large number of items in the CPRA itself, the predictive validity of the CPRA was validated by the use of the QIDS.

Statistical analysis

The demographic characteristics and backgrounds of the participants were summarized using descriptive statistics. Independent exploratory factor analyses were performed using the maximum likelihood method and the Promax rotation method for the five domains of comprehensive psychosocial variables. After extracting the factor structure from several candidates and the interpretability in each domain, item analyses were performed considering factor-loading scores and correlation coefficients between items within the same factor to thereby select the proper items by measuring their factors and excluding redundant items. We performed a factor analysis of the remaining items after item selection to confirm the final factor structure. In addition, we calculated the Cronbach’s α and the factor score for each factor belonging to each domain.

Finally, to confirm content and predictive validity, we performed a hierarchical linear regression on the final items to predict QIDS-J scores as an index of mothers’ psychological adaptation and distress. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 26.

Ethical approval

This study has been approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the Graduate School of Human Sciences, Osaka University (No.19010), and the Ethics Review Committee of Observation Research, Osaka University Hospital (No.19290–2).

Results

Participant backgrounds

The survey included 1,031 participants with a mean age of 31.7(± 5.3) years and a mean number of children was 1.17 (Table 1).

Factor structure and items of comprehensive psychosocial variables

The exploratory factor analyses and item analyses for 118 items in five domains yielded a one-factor structure (5 items) for the category Child’s Temperament and Health, a five-factor structure (20 items) for Environmental Resources, a four-factor structure (15 items) for Perceived Support, a six-factor structure (22 items) for Mother’s Cognitive and Behavioural Characteristics, and a five-factor structure (19 items) for Psychological Adaptation to Parenting (Table 2).

Child’s Temperament and Health

The exploratory factor analysis and the item analysis of seven items in the category Child’s Temperament and Health identified a one-factor structure with five items, with appropriate interpretability (e.g. My child often seems uncomfortable when I hold him/her; Cronbach’s α = 0.645).

Environmental Resources

The exploratory factor analysis and the item analysis of 33 items in the Environmental Resources domain yielded a four-factor structure with 20 items with appropriate interpretability. The subscales were interpreted as follows: (1) Relationship with the Medical Staff (e.g. I think the healthcare workers are reliable; Cronbach’s α = 0.757), (2) Partner Temperament (e.g. My husband [partner] is a difficult person; Cronbach’s α = 0.740), (3) Parental Autonomy (e.g. My parents are good at time management; Cronbach’s α = 0.735), (4) Partner Autonomy (e.g. My husband [partner] is good at time management; Cronbach’s α = 0.706), (5) Child-Rearing/Long-Term Care Burden (e.g. [If you have an older child], the older child needs much care; Cronbach’s α = 0.701).

Perceived Support

The exploratory factor analysis and the item analysis of 15 items in the Perceived Support domain yielded a four-factor structure with 15 items with appropriate interpretability. The subscales were interpreted as: (1) Husband’s/Partner’s Support (e.g. My husband [partner] takes care of our child; Cronbach’s α = 0.846), (2) Parental Support (e.g. My parents help me with childcare; Cronbach’s α = 0.753), (3) Lack of Psychological Support from Husband/Partner(e.g. My husband [partner] takes care of our child, but I sometimes feel lonely; Cronbach’s α = 0.671), (4) Sufficient Social Support (e.g. I have good relationships with my parents; Cronbach’s α = 0.496).

Mother’s Cognitive and Behavioural Characteristics

The exploratory factor analysis and the item analysis of 41 items in the Mother’s Cognitive and Behavioural Characteristics domain yielded a six-factor structure with 22 items with appropriate interpretability. The subscales were interpreted as (1) Inattentiveness (e.g. I often forget something; Cronbach’s α = 0.741), (2) Emotional control (e.g. I am not bothered or upset when my child does not do what I want; Cronbach’s α = 0.649), (3) Systemisation Urge (e.g. I have my ideal form of child-rearing plan, and I want to apply it somehow; Cronbach’s α = 0.691), (4) Simultaneous/Overall Processing (e.g. I am good at doing more than one thing at a time; Cronbach’s α = 0.673), (5) Social Intolerance (e.g. I do not understand the explanations of healthcare workers, such as doctors, during the regular health check-up for my child; Cronbach’s α = 0.577), (6) Attachment Problems (e.g. When I was a child, my parents [or major caregivers] did not take care of me; Cronbach’s α = 0.731).

Psychological Adaptation to Parenting

The exploratory factor analysis and the item analysis of 22 items in the Psychological Adaptation to Parenting domain yielded a four-factor structure with 19 items with appropriate interpretability. The subscales were interpreted as: (1) Lack of Self-Confidence (e.g. I have a lot of concerns about parenting; Cronbach’s α = 0.824), (2) Possibility of Coping (e.g. I feel that I have the time to spend freely; Cronbach’s α = 0.813), (3) Love for the Child (e.g. I love my children; Cronbach’s α = 0.863), (4) Self-Esteem (e.g. I can overcome difficulties; Cronbach’s α = 0.731), (5) Self-Responsibility (e.g. I think it’s my fault that my child doesn’t stop crying; Cronbach’s α = 0.783).

Relationships between psychological maladjustment on the QIDS and the CPRA domains

Correlations with QIDS

The Pearson’s product-moment correlations between the 21 factors on the CPRA’s five domains (i.e. Child’s Temperament and Health, Environmental Resources, Perceived Support, Mother’s Cognitive and Behavioural Characteristics, and Psychological Adaptation to Parenting) and QIDS were calculated. As shown in Table 3, significant correlations with the QIDS were observed for all factors, including weak ones (p < 0.01). In the domain of Mother’s Cognitive and Behavioural Characteristics, the factors of Social Intolerance (r = 0.344), Emotion Control (r = 0.318), Inattentiveness (r = 0.264), and Attachment Problems (r = 0.256) were significantly correlated with the QIDS. Weak correlations were also found between the factors Simultaneous/Overall Processing (r = 0.182) and Systemisation Urge (r = 0.128) and the QIDS.

In the domain of Perceived Support, the QIDS was strongly correlated with Psychological Support from Husband/Partner (r = −0.402). It was also significantly correlated with Sufficient Social Support (r = −0.298) and Husband’s/Partner’s Support (r = −0.239). In addition, a weak correlation was found between the QIDS and the Parental Support (r = −0.139) factor.

In the domain of Psychological Adaptation to Parenting, there was a strong correlation between the QIDS and Self-Responsibility (r = 0.521) and Lack of Self-Confidence (r = 0.439). Significant correlations were also found between Possibility of Coping (r = 0.352), Self-Esteem (r = 0.254), and Love for the Child (r = 0.200) and the QIDS scores.

In the domain of Environmental Resources, a significant correlation was found between the QIDS and the factors of Partner Temperament (r = 0.262) and Relationship with Medical Staff (r = 0.207). A weak correlation was found between the QIDs and the factors Child-Rearing/Long-Term Care Burden (r = 0.187), Partner Autonomy (r = 0.146), and Parent Autonomy (r = 0.103). It was also significantly correlated with the Condition of a Child (r = 0.256) factor in the domain of Child’s Temperament and Health.

CPRA factors predicting QIDS scores in the hierarchical multiple regression analyses

Table 4 shows the results of the six-step hierarchical multiple regression analyses that included the demographic variables and the factor variables from the CPREA to predict QIDS scores as the index for participants’ psychological maladjustment. Model 1 comprised only demographic variables, Child’s Temperament, and Health was entered in Model 2, the Environmental Resources variables in Model 3, the Perceived Support variables in Model 4, Mother’s Cognitive and Behavioural Characteristics variables in Model 5, and Psychological Adaptation to Parenting in Model 6.

In the final model, the amount of change in R2 was significant, then the age of the youngest child, Partner Temperament, Child-Rearing/Long-Term Care Burden, Lack of Psychological Support from Husband/Partner, Inattentiveness, Social Intolerance, Attachment Problems, Lack of Self-Confidence, Possibility of Coping, and Self-Responsibility were significant predictors of the QIDS score (β = -0.065, p = 0.024; β = 0.076, p = 0.012; β = 0.101, p = 0.002; β = − 0.084, p = 0.011; β = 0.100, p < 0.001; β = 0.103, p < 0.001; β = 0.069, p = 0.015; β = 0.122, p < 0.001; β = 0.132, p < 0.001; β = 0.232, p < 0.001, respectively).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to create a comprehensive assessment tool to investigate the psychosocial characteristics of perinatal mothers. The most important finding is that we identified five domains of characteristics: Child’s Temperament and Health, Environmental Resources, Perceived Support, Mother’s Cognitive and Behavioural characteristics, and Psychological Adaptation to Parenting. Two domains—Environmental Resources and Perceived Support—have been identified in previous studies [20]. However, Mother’s Cognitive and Behavioural Characteristics has not been used for comprehensive evaluations in previous studies; therefore, this is an original finding of this study. Assessing these domains may lead to specific and tangible support for mothers after childbirth from various health care professionals. For example, the cognitive and behavioural characteristics measured by CPRA may be related to existing individual characteristics that typically lead to difficulties and stress in situations other than parenting. Understanding mothers’ vulnerabilities at the outset of parenting could help predict long-term adaptation and enable healthcare professionals to develop countermeasures. The domains of Child’s Temperament and Health, Environmental Resources, and Perceived Support contribute to better understanding the kind of supportive environment the mother experiences.

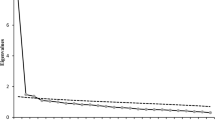

The second important finding is that among these domains, Partner Temperament, Child-Rearing/Long-Term Care Burden, Lack of Psychological Support from Husband/Partner, Inattentiveness, Social Intolerance, Attachment Problems, Lack of Self-Confidence, Possibility of Coping, and Self-Responsibility are factors that significantly explained participants’ depressive tendencies on the QIDS. A study using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, another measure of depression that includes questions on emotions, such as fun, happiness, anxiety, and fear, demonstrated an association between depression and factors such as child temperament, husband support, and self-esteem [21,22,23], consistent with the results of this study. Therefore, the CPRA appears to be a valid evaluation tool for predicting mothers’ mental health issues, including depression (Fig. 1). A notable strength of the CPRA is that it can comprehensively measure both a mother’s emotional status and detailed cognitive and behavioural aspects of her mental health, such as Inattentiveness, Social Intolerance, Attachment Problems, and the presence of sufficient social support.

The results of the CPRA can be utilised in clinical practice. For example, healthcare practitioners can implement measures such as informing the mother, who are at risk for depression, of the specific factor of concern at the time of the examination. Moreover, for mothers who are influenced by external factors, such as psychological support from their partners, it is possible to propose psychological education for both the mother and family. Furthermore, other health professionals working with mothers can use this tool to assess mothers’ cognitive and behavioural characteristics, as these may be difficult for general healthcare professionals to evaluate. This requires the development of an educational programme for evaluation, in addition to the CPRA.

The study is limited by its cross-sectional design. Longitudinal studies are necessary for the future to determine whether the domains and factors measured by this scale predict maternal maladaptation. Our team is currently working on a project to create a cohort of patients who have experienced their childbirth in one perinatal unit to evaluate the prognosis longitudinally.

Conclusions

Maladaptation to parenting is caused by a combination of multiple factors. Understanding how these factors interact via the CPRA makes it possible to predict the probability. When a mother is predicted to fall into child-rearing maladjustment, a comprehensive model can be used to show concretely and specifically what kind of support is needed for that mother. The mother, her family, and her child-rearing supporters can implement measures to prevent the mother from becoming maladjusted. Similarly, it is possible to understand which support is most effective in the event of childcare maladjustment. As this study focuses on the child-rearing behaviour of mothers, researching the child-rearing behaviour of fathers may lead to results that further support parents’ challenges and struggles related to child-rearing difficulties. In addition, the influence of culture on the results needs to be considered in the future. Especially during a pandemic where antenatal and postnatal services are likely to be affected.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets during and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CPRA:

-

Comprehensive scale for parenting resilience and adaptation

- EPDS:

-

Edinburgh postnatal depression self-evaluation scale

- QIDS:

-

Quick inventory of depressive symptomatology

References

Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1071–83.

Shiino T. Shusanki no sosharusapoto ga boshikankei ni oyobosu eikyo. [Impact of perinatal social support on mother-child relationships]. Stress Sci Res. 2016;31:74–5 (Japanese).

Bloomfield L, Kendall S. Parenting self-efficacy, parenting stress and child behaviour before and after a parenting programme. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2012;13:364–72.

Kanagawa T, Wada S, Okamoto Y, Kawaguchi H, Hirata E, Mitsuda N. Osakafu ni okeru ninsanpu no shienjigyo (Tokushu kokoromo miru) [I also look at my heart. Support project for pregnant women in Osaka Prefecture (commentary/special feature)]. J Jpn Soc Perinatal Mental Health. 2019;5(1):7–13 (Japanese).

Shimada Y, Sugihara K, Hashimoto M. Ikuji sutoresu ya ikujifuan wo kakaeru hahaoya heno ikujishien no jissai to sono koukani tuiteno bunken rebuy [Literature review on the actual situation and effects of childcare support for mothers with childcare stress, childcare anxiety, and childcare difficulties]. Bull Nurs Res. 2019;7(1):69–81 (Japanese).

Gibson J, McKenzie-McHarg K, Shakespeare J, Price J, Gray R. A systematic review of studies validating the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in antepartum and postpartum women. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;119(5):350–64.

Stasik-O’Brien SM, McCabe-Beane JE, Segre LS. Using the EPDS to identify anxiety in mothers of infants on the neonatal intensive care unit. Clinical Nurs Res. 2017;28(4):473–87.

Kawano A. Sangoutsu no yoboutekishienn oyobi soukihakken ni mukete -kyakkanteki shihyoutoshite baio maka wo katuyousuru [Clinical usefulness of the biomarker for assessment of postpartum depression]. Precis Medicine. 2019;2(14):1370–5 (Japanese).

McLeish J, Redshaw M. Mothers’ accounts of the impact on emotional wellbeing of organised peer support in pregnancy and early parenthood: a qualitative study. BMC Preg Childbirth. 2017;17:28.

Kobayashi N, Takahashi H, Tsukada Y. Shosanpu ni okeru jitsubo tono kankeisei ga ikujikonnankan ni ataeru eikyo [Effect of relationship with mother in primiparas on childcare difficulty]. Matern Hyg. 2018;59(3):324 (Japanese).

Fujioka N, Kato N, Hamada N. 1saiji no hahaoya ga idaku ikujikonnankan to otto no ikujisanka ni taisuru manzokudo tono kankei-1sai6kagetsu kenshin jushinji no jittaichousa yori [Relationship between mother’s difficulty in childcare and husband’s satisfaction with childcare participation: from a fact-finding survey at the time of a 1 year and 6 month medical examination]. Matern Hyg. 2013;54(1):173–81 (Japanese).

Akimoto M, Saito I, Sakiyama T. Sango 1kagetsu madeno hahaoya no hiroukan ni eikyosuru youin no kentou [Examination of factors affecting mother’s feeling of fatigue up to one month after giving birth]. Jpn Public Health Mag. 2018;12:769–76 (Japanese).

Sasaki M, Soto C, Kudo H, Nagatoshi A. Asuperugashoukougun gappeishou josei no ninshin/shussan/ikujishien ni kansuru kosatsu-kodawari ya rikairyoku ni tokucho no aru jirei heno apuro-chi [Consideration on pregnancy, childbirth, and childcare support for women with Asperger’s syndrome. Approach to cases characterized by commitment and understanding]. Proceedings of the Japan Nursing Society. Health Promot. 2015;45:101–4 (Japanese).

Baraitser L, Noack A. Mother courage: reflections on maternal resilience. Br J Psychother. 2007;23(2):171–88.

Miyano Y, Fujimoto M, Yamada J, Fujiwara C. Ikuji rejiriensushakudo no kaihatsu [Development of a Scale to Measure Resilience in Child Care]. J Child Health Nurs. 2014;23(1):1–7 (Japanese).

Grotberg,EH. A guide to promoting resilience in children: strengthening the human spirit. Early Childhood Development: Practice and Reflections, v8. 1995; Bernard Van Leer Foundation.

Hiew,C. C. Child resilience: Conceptual and evaluation issues. In: Proceedings of the 23rd child learning forum, Osaka, 1998:21–24.

Matsuo T, Nakamura C. Daremo Oshietekurenakatta inshibunseki Kitaoji-shobo. 2002 (Japanese).

Fujisawa D, Nakagawa A, Tajima M, Sado M, Kikuchi T, Iba M, et al. Nihongoban jikokinyushiki kani yokuutushakudo(nihongoban QIDS-SR)no kaihatsu [Development of Japanese version of self-administered simple depression scale (Japanese version of QIDS-SR)]. Stress Sci. 2010;25(1):43–52 (Japanese).

Neece CL, Green SA, Baker BL. Parenting stress and child behavior problems: a transactional relationship across time. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2012;117(1):48–66. https://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-117.1.48.

Milgrom J, Gemmill A, Bilszta JL, et al. Antenatal risk factors for postnatal depression: a large prospective study. J Affect Disord. 2008;108:147–57.

Ida A. Wagakuni niokeru “hahaoya no ikujikonnankan” no gainenbunseki: Rodgers no gainenbunseki wo mochiite [A conceptual analysis of ‘mothers’ perception of difficulty in raising children’ in Japan: using Rodgers’ concept analysis method]. J Hum Care Res. 2013;4(2):23–30 (Japanese).

Kobayashi S. Nyuyouji wo motsu hahaoya no sosharusapoto to yokuutujoutai tono kanren [The relationship between social support and depressive state among mothers caring infants]. Pediatric Health Res. 2008;67(1):96–101 (Japanese).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor. T. Kimura, and the members of Research of Watching Over the First 1000 days of Life of Osaka University for promoting this research. We also thank Y. Shimizu for her assistance in translating the questioners into English. This work is supported by a Grant from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) to support research centers for the Realization of Society 5.0.

Funding

Grant from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) to support research centers for the Realization of Society 5.0.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ME, KH, and SS: Conception and design of the study. KH and SS: Collection, analysis and interpretation of data. SS: Drafting of the article. SS and KH: Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the Graduate School of Human Sciences, Osaka University (No. 19010) and the Ethics Review Committee of Observation Research, Osaka University Hospital (No. 19290-2). All methods of this study were carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all study participants when they completed the questionnaire online.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest directly relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Sugao, S., Hirai, K. & Endo, M. Developing a Comprehensive Scale for Parenting Resilience and Adaptation (CPRA) and an assessment algorithm: a descriptive cross-sectional study. BMC Psychol 10, 38 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-022-00738-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-022-00738-3