Abstract

Background

The PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome (PHTS) encompasses several different syndromes, which are linked to an autosomal-dominant mutation of the tumor suppressor PTEN gene on chromosome 10. Loss of PTEN activity leads to an increased phosphorylation of different cell proteins, which may have an influence on growth, migration, and apoptosis. Excessive activity of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway due to PTEN deficiency may lead to the development of benign and malignant tumors and overgrowth. Diagnosis of PHTS in childhood can be even more challenging than in adulthood because of a lack of well-defined diagnostic criteria. So far, there are no official recommendations for cancer surveillance in affected children and adolescents.

Main body

All individuals with PHTS are at high risk for tumor development and thus might benefit from cancer surveillance strategies. In childhood, macrocephaly may be the only evident symptom, but developmental delay, behavioral problems, dermatological features (e.g., penile freckling), vascular anomalies, lipoma, or enlarged perivascular spaces in cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI) may help to establish the diagnosis. Regular psychomotor assessment and assistance in subjects with neurological impairment play an important role in the management of affected children. Already in early childhood, affected patients bear a high risk to develop thyroid pathologies. For that reason, monitoring of thyroid morphology and function should be established right after diagnosis. We present a detailed description of affected organ systems, tools for initiation of molecular diagnostic and screening recommendations for patients < 18 years of age.

Conclusion

Affected families frequently experience a long way until the correct diagnosis for their child’s peculiarity is made. Even after diagnosis, it is not easy to find a physician who is familiar with this rare group of diseases. Because of a still-limited database, it is not easy to establish evidence-based (cancer) surveillance recommendations. The presented screening recommendation should thus be revised regularly according to the current state of knowledge.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome (PHTS) compromises several different syndromes, which are linked to an autosomal-dominant mutation of the tumor suppressor gene PTEN on chromosome 10. Loss of PTEN activity leads to an increased phosphorylation of different cell proteins, which may have an influence on growth, migration, and apoptosis. Excessive activity of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway may lead to the development of benign and malignant tumors and overgrowth. Cowden Syndrome (CS) and Bannayan–Riley–Ruvalcaba syndrome (BRRS) are associated to PTEN gene mutations, but also Proteus/Proteus-like syndrome, autism spectrum disorders with macrocephaly, Lhermitte–Duclos syndrome, and juvenile polyposis of infancy have been linked to PTEN gene mutations. All individuals with PHTS are at high risk for tumor development and benefit from cancer surveillance strategies, because in general, tumor detection in an early stage may lead to lower mortality rates and decreased risk for complications. There is no clear evidence for differences in the incidence of different types of cancer in the different PTEN-attributed syndromes or a distinct genotype–phenotype correlation. Therefore, at the current state of knowledge, we are not able to differentiate screening recommendations for the different syndromes. The most frequent affected organs are the breast, endometrium, and thyroid. Thyroid cancer has been reported already in very young children [1,2,3]. Most patients exhibit an increased head circumference already early in life (more than + 2 SDS above the age and population–related mean or > 97th percentile) [4,5,6,7,8]. Our own data showed that all patients exhibited a head circumference > 97th percentile by the age of 2 years. Most male patients already showed a macrocephaly at birth, and the extend was more pronounced than in female patients [8]. Developmental delay, especially a delay in motor development is described frequently without a clear genotype–phenotype correlation. PHTS is a rare disease with a prevalence of 1:200.000 to 1:250.000 [9, 10]. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) published guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of adult PHTS patients [11]. However, official pediatric guidelines are lacking. Children frequently do not fulfill the known diagnostic criteria for adult patients. Therefore, diagnosis of PHTS in childhood may be even more challenging than in adulthood. Furthermore, cancer surveillance strategies should be different, since the risk of tumor development in childhood differs from adult patients. Mostly, malignant tumors are reported in adults. In children, there are only case reports of malignant tumors, except for the thyroid, which is frequently affected. With this article, we would like to increase knowledge of this rare disease, in order to facilitate an earlier diagnosis of affected subjects. Supported by the German Society for Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetology (DGKED) and in cooperation with several other societies (German Society for Human Genetics (GfH), German Society of Pediatrics (DGKJ) German Society for Pediatric Oncology and Hematology (GPOH), German Society for Neuropediatrics (GNPI), German Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition (GPGE), and the German Patient Support Group (CoBald)), we developed a pediatric guideline for the diagnosis and management of PHTS in childhood and adolescence, in order to aid physicians in the diagnosis, surveillance, and management of their patients. For this guideline, we performed a nonsystematic search in https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov including, but not limited to, the following key words: “PTEN Hamartoma Tumor Syndrome AND children”, “PHTS AND Children AND Thyroid”, “PTEN AND Children AND Thyroid”, “PHTS AND Guideline”, “Macrocephaly AND PTEN”. This search was extended by publications cited by some of the keyword-driven publications, finally updated in July 2021.

Syndromes and phenotypes which are associated with PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome (PHTS)

Cowden syndrome and Bannayan–Riley–Ruvalcaba syndrome (BRRS)

Cowden syndrome is the most commonly known syndrome associated with a germline mutation of the tumor suppressor gene PTEN. BRRS and Cowden syndrome can be seen as one condition with variable expression and age-related penetrance [4, 12]. Within this perspective, BRRS describes the typical manifestation of the disease in childhood, whereas Cowden syndrome describes the clinical manifestation more evident in adulthood. There is a smooth transition between both entities. Typical clinical manifestations for both syndromes are an increased head circumference above the 97th percentile and a variety of hamartomata, such as hemangioma, lipoma, and gastrointestinal polyps. The latter may cause intussusception or rectal bleeding [4,5,6,7,8]. PHTS patients are at high risk to develop benign and malignant tumors.

Proteus syndrome/Proteus-like syndrome

Proteus syndrome is a very rare condition and quite variable in its phenotype. Overgrowth of different body parts like skin, bone, muscles, fat tissue, and blood or lymph vessels is frequently observed. The risk for tumor development is significantly increased. It is usually associated with a mutation in the AKT-1-gene. In rare cases, mutations in the PTEN gene have also been described. Except for the macrocephaly, the clinical presentation of children with Proteus syndrome differs relevantly from patients with CS or BRRS. Their specific treatment is not part of this review.

Autism spectrum disorder with macrocephaly

In patients with autism spectrum disorder in combination with macrocephaly, a PTEN gene mutation has been detected in 10 to 27% [13,14,15,16]. The currently available data suggest that the likelihood of identifying PTEN mutations is higher in individuals with autism spectrum disorder with more pronounced macrocephaly [15, 17].

Lhermitte–Duclos syndrome

Lhermitte–Duclos syndrome is a variant of CS and is characterized by slowly growing hamartomatous tumors of the cerebellum (cerebellar dysplastic gangliocytoma) and occurs typically in adults. Associated symptoms depend on the tumor size and include ataxia, elevated intracranial pressure, and seizures.

Juvenile polyposis of infancy

Juvenile polyposis of infancy is a very rare condition and is caused by deletions of the BMPR1A and PTEN genes. Patients suffer from gastrointestinal bleeding, diarrhea, and a severe protein-losing enteropathy. Further clinical manifestations might resemble BRRS [16].

Clinical phenotype and respective monitoring recommendations of PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome in children and adults

Recommendations for cancer surveillance of adults with PHTS were previously published by NCCN and others [11, 18, 19]. However, children and adolescents with PHTS were not or inadequately considered in those recommendations. Therefore, we propose a specific monitoring regime for children and adolescents. After diagnosis of a PTEN gene mutation in children, we recommend timely genetic counselling including the opportunity for an analysis regarding a PTEN gene mutation in relatives (especially parents and siblings). Affected families need to be informed about the variability of the clinical spectrum and potential complications of this rare disease. If possible, the explaining clinician should have expertise in this field. All patients with PTEN gene mutations should have an annual comprehensive physical examination.

Central nervous system

Macrocephaly

As mentioned above most patients with PHTS exhibit a marked macrocephaly early in life (up to 2 years of life) with a head circumference standard deviation score of + 3 SDS and more. Therefore, head circumference, but neither height nor weight development, might be useful to establish an earlier diagnosis of PHTS [8].

Development, intelligence, and imaging in cerebral MRI

Frequently, children with PHTS demonstrate a variable degree of developmental delay. Most patients show a delay in motor development. A fraction of patients presents with muscle hypotonia and proximal myopathy, which at the time might be the leading clinical problem. Intellectual disabilities may be present, but with a high variability [16] from severe cases to subjects with normal intelligence. In our cohort and in others [20, 21], the majority of patients had a mean intelligence quotient (IQ) within the normal range. The prevalence of autism spectrum disorders in patients with PHTS is estimated around 22% [22, 23] and therefore higher than in the general population with around 1% [24].

Most children with PHTS receive a cerebral MRI as part of the diagnostic workup of macrocephaly. A high percentage shows enlarged perivascular spaces (EPVS) and white matter abnormalities. Therefore, detecting these abnormalities in cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI) might also help in establishing an earlier diagnosis in PHTS patients [20] (Fig. 1). In childhood, psychomotor assessment and, if necessary, further neurological diagnostic and treatment play a central role in the management of patients with PHTS. Muscle hypotonia might be treated with physiotherapy or supporting medical devices. In case of severe neurological symptoms or recurrent headaches, a cerebral MRI should be performed. In adults, cerebellar dysplastic gangliocytoma (Lhermitte–Duclos syndrome) should be excluded. Vascular malformations could be located anywhere and cause diverse symptoms. To the best of our knowledge, there is no proved genotype–phenotype correlation for the extent of neurological symptoms.

Skin

Typical skin manifestations in childhood are hamartomata such as lipoma and hemangioma. In males with a PTEN gene mutation, penile freckling could be a useful diagnostic feature, since it is described in about half of all male cases [18, 20]. Penile freckling (Fig. 2) may not be evident in infants, but usually develops until mid-childhood. Later in life, mostly in the second or third decade, nearly all patients exhibit typical mucocutaneus symptoms, for example trichilemmoma, oral mucosa papillomatosis, palmoplantar keratosis, or hyperplasia of the gingiva [18]. The risk for melanoma seems to be elevated in patients with PHTS [18]. Cumulative lifetime risk for melanoma is reported to be around 6% [19] with the youngest patients being reported to be 3 [19] and 6 [18] years old. Even though there are only single reports of melanoma in children with PHTS, we recommend yearly dermatological examinations and advice to take care of UV protection.

Benign and malignant tumors

Subjects with PTEN gene mutation harbour an increased risk for tumor development of thyroid malignancies occurring already in young children. Riegert-Johnson [25] estimated cumulative lifetime (age 70 years) risks of 89% for any cancer diagnosis.

Breast

Almost all women with PTEN gene mutation have an involvement of the breast [26], including benign and malignant tumors. Already adolescents may develop multiple benign tumors of remarkable size, for example fibroadenoma, tubular adenoma, or atypical ductal hyperplasia (Fig. 3). To the best of our knowledge, breast cancer has been described only in adult women, even though there are case reports of very young women (22 years) with PHTS suffering from breast cancer [26]. Similar to women who carry BRCA gene mutations, women with PHTS tend to develop breast cancer in younger years. Mean age at diagnosis is 36 to 46 years [9]. Riegert-Johnson et al. [25] report a cumulative lifetime risk of breast cancer in women with PHTS of 81%. Other authors estimate the risk between 25 to 85% [18, 22, 27]. Single cases of breast cancer have also been reported in men [28,29,30].

We recommend, that systematic breast awareness of females with a PTEN gene mutation should start at the age of 18 years monthly. Clinical examination is recommended at the age of 25 years (or 5–10 years before youngest age of cancer diagnosis in the family) twice per year. MRI of the breast and mammography are recommended to start latest at the age of 35 years (or 5–10 years before youngest age of cancer diagnosis in the family).

Thyroid

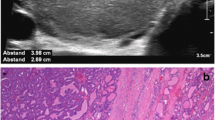

Up to 75% of all patients demonstrate thyroid pathologies such as nodules, goiter, and autoimmune thyroid disease [1]. The cumulative lifetime risk of patients with PTEN gene mutations to develop thyroid carcinoma is estimated between 21 and 38% [16, 18, 22, 25, 31]. In most cases, patients develop follicular carcinoma, rarely papillary thyroid cancer. Single cases of medullary carcinoma have been described [31]. The development of thyroid pathologies, including thyroid cancer might occur already early in life [1,2,3, 19], with the youngest reported patient with a thyroid carcinoma being 6 years old [1]. Pediatricians should be aware of the early thyroid involvement and possible thyroid cancer development in PHTS patients. We found no evidence for an improved outcome in children with PHTS and an early detection of thyroid carcinoma. But some evidence could be found in non PHTS patients, especially for adults. Detection in an early stage leads to a lower mortality rate (high level of evidence for adults, very low level of evidence for children) and a decreased risk of hypoparathyroidism (high level of evidence for adults) [32], and it was found to lead to lower recurrence rates (moderate to low level of evidence for adults; very low level of evidence for children).

Therefore, we recommend annual ultrasound screening of the thyroid, independent of the age at diagnosis. We propose an annual examination interval, which should be adapted in case of any suspicious results [1]. Beginning and interval of surveillance are a subject of discussions. Jonker et al. [33] analyzed five cohort studies where the incidence for differentiated thyroid carcinoma ranged between 4 and 12%, and recommended to start screening for differentiated thyroid carcinoma, when the risk exceed 5%. This is in concordance to other childhood tumors with an excellent prognosis. In their analysis, most cases were diagnosed between the ages of 10 and 14 years, so that they recommend surveillance from the age of 10 years onwards, since at that age, the incidence of thyroid carcinoma seems to reach 5%. Smith et al. [34] performed a retrospective cohort study of 64 children with PHTS. Clinically significant thyroid nodules (≥ 10 mm diameter) developed in 44% of 50 patients who underwent thyroid ultrasound at a median age of 13.3 years. Nodules were rare prior to the age of 7 years. Prevalence was increasing around the age of puberty with an earlier appearance in girls. Thyroid cancer was diagnosed in 2 patients (4%). Their findings indicated, that children without or with only small nodules (< 5 mm) were unlikely to develop significant nodules ≥ 10 mm within 2 years, whereas nodules ≥ 5 mm showed a likelihood of 20% to grow ≥ 10 mm within 1 year. Both groups [33, 34] elaborate that early screening might lead to overdiagnosis and anxiety of families. On the other hand, another group [35] with a small case series reported that nearly half of their subjects, who had nodular thyroid disease were younger than 7 years of age. Based on these results [33,34,35], the interval of surveillance may be prolonged two biannual or every 3 years in young children (< 7 years of age) if they do not have proof of nodules in ultrasound screening. If there is a nodule with suspicious ultrasound findings (e.g., size > 10 mm, central hyperperfusion, irregular margin, microcalcifications, quickly growing size), further diagnosis of dignity is indicated. We recommend fine-needle biopsy (FNB), where it is both appropriate and possible. However, we do see some limitations for FNB. Most pediatric patients, especially those who may have behavioral specifics like autism would frequently need general anesthesia to undergo this procedure. Fine-needle biopsy may not be sufficient to exclude malignancy in cases of more than one suspicious lesion, which is common in patients with PHTS. It is not possible to distinguish a benign follicular adenoma from a follicular carcinoma by cytological analysis, but most PHTS patients exhibit follicular lesions [36]. Because of multicentricity and increased risk of recurrence or progression to carcinoma [2, 11, 37, 38], we agree with other groups that total thyroidectomy should be recommended when a surgical intervention is indicated. Surgical intervention should be performed by an endocrine surgeon with experience in the treatment of children.

Urogenital system (endometrium, gonads, renal system)

The lifetime risk to develop endometrial carcinoma in women is reported to be 19–28% [19, 25] compared with the general population with 2.1% with a mean age of 69 years [31]. Except for one 16-year-old girl with granulosa cell tumor, gonadal tumors were not described in PHTS [3]. Testicular lipomatosis is described in adult males with PTEN gene mutation. We recommend testicular ultrasound at the beginning of puberty around the age of 10 years. The cumulative lifetime risk (age 70 years) for renal cancer is elevated and appraised to be around 15% (CI = 6%, 32%) [25]. As the youngest patient with a PHTS associated renal cell carcinoma was diagnosed at the age of 11 years [3], we recommend abdominal ultrasound once every year, starting with diagnosis, even though most cases of renal tumors were reported in adult subjects.

Gastrointestinal manifestations

In 95% of affected subjects, the gastrointestinal tract is part of the phenotypical spectrum [39,40,41,42,43,44]. This encompasses hamartomatous, inflammatory, adenomatous, ganglioneuromatous, hyperplastic, and juvenile polyps which may be located in all parts of the gastrointestinal tract with a focus on the rectum and sigmoid. Dissemination and severity may differ between cases. A typical clinical manifestation is perianal bleeding. The lifetime risk to develop colon carcinoma is estimated from 9 [22] to 16% [25]. Age at diagnosis of colon carcinoma is mostly around 50 years of age [39]. There are no descriptions of colon carcinoma in childhood. Acanthosis of esophagus [5, 42] and eosinophilic esophagitis [43] may be further gastrointestinal pathologies in young patients with PHTS. Even though hamartomatous polyps are found early in childhood, the majority of children are not symptomatic. In contrast, patients with a deletion of the BMPR1A and PTEN gene show a severe clinical picture of juvenile polyposis of infancy and need early gastrointestinal diagnostics and treatment. The American guideline for hereditary gastrointestinal cancer syndromes [41] recommends gastroscopy and colonoscopy for patients with PHTS starting at the age of 15 years every 2 years. Other authors point out different recommendations starting at the age of 35 years [16, 45], because colorectal tumors have been mostly diagnosed at the end of the fourth decade of life [22]. We recommend to differentiate whether patients show symptoms or not. In patients without any complaints, endoscopy to detect tumor development seems to be sufficient at the age of 35 years. In contrast, patients with symptoms like hematochesis, severe constipation, diarrhea, or recurrent and severe abdominal pain should receive early diagnostic intervention. Because rectal bleeding and the development of anemia could be symptoms of polyps, we recommend to screen for bleeding anemia.

Lipomatosis

A lipoma may develop a remarkable size and may therefore have space compromising effects, depending on their localization (Fig. 4). Size and growth might be monitored by ultrasound or MRI scan. As long as there are no space-compromising effects or cosmetic impairments, lipomas do not need an intervention.

Vascular anomalies

Regulation of angiogenesis is one function of the PTEN gene. Loss of PTEN gene function could therefore be associated with vascular anomalies. Vascular anomalies/malformations can be localized at any part of the body. Prevalence of vascular anomalies in PHTS is still unclear, but some reports estimated the presence of these in at least one third of the affected subjects [22, 44]. Tan et al. [46] present a collective of 26 pediatric patients of whom 14 patients presented vascular anomalies. The age at first vascular symptom, defined to the age when the vascular anomaly was first noticed by either the patient or doctor, ranged from birth (three patients) to 16 years of age. Vascular anomalies usually present as cutaneous discoloration, swelling, or pain [22, 46]. Physicians should be aware of possible symptoms of vascular anomalies in physical examination and ask the patients and parents, if they have any symptoms of skin discoloration, swelling, or pain. Dural [22], intracranial developmental venous anomalies (DVAs) [46] and large visceral [47], vertebral [48], and intestinal arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) [44, 49] have been reported. Intestinal arteriovenous malformations may lead to extensive blood loss and severe anemia [44, 49]; vertebral AVMs may lead to destruction of the vertebral body [48]. Takaya et al. [50] described the management of a patient with a clinical diagnosis of CS who presented with multiple large AVMs at the age of 30 years. The lesions caused high-output cardiac failure and subsequent death of the patient. Clinicians should be aware of the risk of hemodynamically significant AVMs in PHTS [47]. For more detailed information of the anomalies, imaging diagnostics should be added (for example sonographic images, angio-MRI).

Immunology

Chen et al. [51] found autoimmunity and peripheral lymphoid hyperplasia in 43% of 79 patients with PHTS. Lymphoid hyperplasia may include gastrointestinal lymphoid hyperplasia, extensive hyperplastic tonsils, and thymus hyperplasia; autoimmunity may include autoimmune lymphocytic thyroid disease, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, and colitis [52]. Immune dysregulation in patients with PHTS include lymphopenia, CD41 T-cell reduction, and changes in T- and B-cell subsets [51]. Although total CD41FOXP31 Treg cell numbers are reduced, frequencies are maintained in the blood and intestine. Despite pathogenic PTEN gene mutations, the FOXP31 T cells are phenotypically normal. Assembly of the PTEN-PHLPP phosphatase network allows coordinated phosphatase activities at the site of T-cell receptor activation, which is important for limiting PI3K hyperactivation in Treg cells despite PTEN haploinsufficiency [51]. Reduced activity of PTEN affects homeostasis of human germinal center B cells by increasing PI3K-AKT signaling via mammalian target of rapamycin as well as antiapoptotic signals [52]. Everyday, clinical relevance of the immunological changes in PHTS is still unclear. Therefore, at the current time, we cannot give substantial clinical recommendations.

Metabolism and obesity

PTEN haploinsufficiency seems to be a monogenic cause of profound constitutive insulin sensitization that is apparently obesogenic [53]. The patients’ insulin sensitivity could be explained by the presence of enhanced insulin signaling through the PI3K-AKT pathway, as evidenced by increased AKT phosphorylations [53]. In this context, there are several case reports of children with PTEN gene mutations and recurrent hypoglycemia [54,55,56]. In our own cohort of children [8] with PTEN gene mutations, the majority of patients had a BMI-SDS above the 50th percentile. The percentage of overweight and obesity in the younger age groups was elevated compared with the German reference data [57].

Diagnostic criteria of PHTS and indications for genetic analyses

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) [11] and others [58] published recommendations for diagnostic criteria of PHTS, distinguishing between major criteria and minor diagnostic criteria. In case, that at least three major criteria or two major and three minor criteria are fulfilled or if there is a familiar case and two major or one major and two minor criteria are fulfilled, molecular testing for PTEN gene mutation should be initiated. Tan et al. [22] pointed out that significant differences in the clinical phenotype of children and adults with PTEN gene mutation exist, with all children in the reported study exhibiting macrocephaly. The majority showed developmental delay or some kind of autism spectrum disorder. Because children show different or less symptoms compared with adults, Tan et al. proposed specific diagnostic criteria for children. Comparably, in the German pediatric guideline, we propose a modified diagnostic algorithm for children and adolescents with PTEN gene mutations (see Tables 12, and 3; Fig. 5). This diagnostic algorithm addresses all subspecialties who care for children, with focus on general pediatricians, pediatric neurologists, radiologists, pediatric endocrinologists, and geneticists. In case of doubt, the patients should be presented to a clinical geneticist.

Therapy

Treatment of benign and malignant tumors in patients with PTEN gene mutation does not differ from treatment strategies in other patients.

Medical treatment

PTEN gene encodes a phosphatase, which regulates PI3K-AKT-mTor signaling. As a result of the mutation, excessive activity of this pathway leads to overgrowth and tumor development. Inhibition of mTOR signaling is a promising target for a possible medical treatment. Single case reports have described the successful use of the mTOR inhibitor sirolimus in patients with segmental overgrowth and PTEN germline mutation [60,61,62,63]. There are ongoing investigations on sirolimus treatment in segmental overgrowth syndromes that also include children. Because of the still-limited state of knowledge at the time, mTOR inhibitors should only be used in clinical studies or on a carefully proofed case-by-case basis.

Surgery

Surgical treatment of patients with PHTS does not differ from respective treatment of other patients. In case of thyroid nodules where malignancy could not be excluded, we recommend total thyroidectomy, because of the risk of multicentricity and recurrence in patients with PHTS. Surgical intervention should be performed by an endocrine surgeon with experience in the treatment of children.

Psychomotor development and psychosocial and pedagogical aspects

Despite the possible tumor development and its treatment, patients and families often face numerous additional issues in children and adolescents with PHTS, that are quite or even more challenging. Affected children might exhibit variable degree of developmental delay, that might require treatment (e.g., by physiotherapy or ergotherapy). Some patients need supporting medical devices due to muscle hypotonia. Autism spectrum disorders and behavioral problems can play a major role in some patients. Intellectual abilities are very variable, and some patients might face problems in daily school life. For these reasons, neurological, physiotherapeutic, ergotherapeutic, and psychological treatments might be needed. If the child shows aspects on autism spectrum disorders, it is advisable to consult an expert for autism. To realize those problems and to possibly establish professional therapies, we recommend to ask for the psychological burden of patients and family at the annual comprehensive physical examination.

Recommendations for children and adolescents with PHTS

In brief, recommendations are as follow:

-

1)

Genetic counselling after diagnosis

-

2)

Annual comprehensive physical examination

-

3)

Psychomotor assessment in children and adolescents

-

4)

Ultrasound examination of the thyroid right after diagnosis

Annual examinations and interval of thyroid ultrasound, which has to be adapted in case of any suspicious result. Children < 7 years of age without proof of nodules in ultrasound screening may have a longer screening interval (2–3 years).

We recommend a low threshold for early surgical intervention (preferably total thyroidectomy).

-

5)

Awareness of possible rectal bleeding and anemia. Early diagnostic intervention in patients with gastrointestinal symptoms like hematochesis, severe constipation, diarrhea, and recurrent and severe abdominal pain. In asymptomatic patients, we recommend gastro- and colonoscopy by the age of 35 years for cancer surveillance at least every 5 years.

-

6)

Breast awareness should start latest by the age of 18 years, clinical breast examinations by the age of 25 years, and imaging (breast MRI/mammography) by the age of 35 years or 5–10 years before youngest cancer diagnosis in family.

-

7)

Yearly dermatological examination and adequate skin protection

-

8)

Yearly abdominal ultrasound. Testicular/uterus and ovarian ultrasound starting around the beginning of puberty (with 10 years of age)

-

9)

Performance of cMRI in the presence of neurological symptoms or signs

-

10)

Medical treatment with mTOR inhibitors should only be used in clinical studies or on a carefully evaluated case-by-case basis

-

11)

Surgical treatment does not differ from other persons

-

12)

Surveillance of psychological burden of patients and families

Conclusion

The PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome is rare, and therefore, diagnosis is often delayed. Families of affected children frequently encounter problems to find medical staff who is familiar with symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment of children with PHTS. Parents often have a high burden concerning psychomotor development, behavioral problems, autism spectrum disorders, and the known elevated tumor risks of their child. There are only limited data of tumor prevalence in childhood, making it difficult to find an adequate balance between too much or too little and too early and too late cancer surveillance. Because of a still-limited database, it is not easy to establish evidence-based (cancer) surveillance recommendations. Most recommendations rely on expert opinions. The recommendations of this article have to be revised regularly on the current state of knowledge.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Abbreviations

- PHTS:

-

PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome

- cMRI:

-

Cerebral magnetic resonance imaging

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- CS:

-

Cowden syndrome

- BRRS:

-

Bannayan–Riley–Ruvalcaba syndrome

- DGKED:

-

German Society for Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetology

- GfH:

-

German Society for Human Genetics

- DGKJ:

-

German Society of Pediatrics

- GPOH:

-

German Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition

- GNPI:

-

German Society for Neuropediatrics

- GPOH:

-

German Society for Pediatric Oncology and Hematology

- CoBald:

-

German Patient Support Group

- GIT:

-

Gastrointenstinal tract

- IQ:

-

Intelligence quotient

- EPVS:

-

Enlarged perivascular spaces

- FNB:

-

Fine-needle biopsy

- e.g.:

-

For example

- DVAs:

-

Developmental venous anomalies

- AVMs:

-

Arteriovenous malformations

- NCCN:

-

National Comprehensive Cancer Network

References

Plamper M, Schreiner F, Gohlke B, Kionke J, Korsch E, Kirkpatrick J, Born M, Aretz S, Woelfle J (2018) Thyroid disease in children and adolescents with PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome (PHTS). Eur J Pediatr. 177(3):429–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-017-3067-9 Epub 2017 Dec 22

Smith, J.R.; Marqusee, E; Webb, S; Nose, V; Fishman, S.J.; Shamberger, R.C.; Frates, M.C.; Huang, S.A. (2011). Thyroid nodules and cancer in children with PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome. JClinEndocrinol Metab 96(1):34–37. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2010-131513.

Smpokou, P; Fox, V.L.; Tan, W.H. (2015). PTEN hamartoma tumour syndrome: early tumour development in children. Arch Dis Child 100(1):34–37. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild2014-305997

Marsh DJ, Kum JB, Lunetta KL, Bennett MJ, Gorlin RJ, Ahmed SF, Bodurtha J, Crowe C, Curtis MA, Dasouki M, Dunn T, Feit H, Geraghty MT, Graham JM Jr, Hodgson SV, Hunter A, Korf BR, Manchester D, Miesfeldt S, Murday VA, Nathanson KL, Parisi M, Pober B, Romano C, Eng C et al (1999) PTEN mutation spectrum and genotype-phenotype correlations in Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome suggest a single entity with Cowden syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 8(8):1461–1472

Parisi MA, Dinulos MB, Leppig KA, Sybert VP, Eng C, Hudgins L (2001) The spectrum and evolution of phenotypic findings in PTEN mutation positive cases of Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome. J Med Genet. 38(1):52–58

Mester JL, Tilot AK, Rybicki LA, Frazier TW, Eng C (2011) Analysis of prevalence and degree of macrocephaly in patients with germline PTEN mutations and of brain weight in Pten knock-in murine model. Eur J Human Genetics 19:763–768

Starnik TM, Van der Veen JP, Arwert F, de Waal LP, de Lange GG, Gille JJ, Eriksson AW (1986) The Cowden syndrome: a clinical and genetic study in 21 patients. Clinc Genet 29:222–233

Plamper M, Gohlke B, Schreiner F, Woelfle J (2019) Phenotype-driven diagnostic of PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: macrocephaly, but neither height nor weight development, is the important trait in children. Cancers 11(7):975. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11070975

Farooq, A; Walker, L.J.; Bowling, J; Audisio, R.A. Cowden syndrome. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36(8):577-83. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.04.002. Epub 2010 May 23.16 17)

Nelen, M.R.; Kremer, H; Konings, I.B.; Schoute, F; van Essen, A.J.; Koch, R; Woods, C.G.; Fryns, J.P.; Hamel, B; Hoefsloot, L.H.; et al.. Novel PTEN mutations in patients with Cowden disease: absence of clear genotype-phenotype correlations. Eur J Hum Genet. 1999;7(3):267-273.

The NCCN 1.2014 genetic/familial high-risk assessment: breast and ovarian, version 1.2014. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014; 12(9):1326-1338

Lachlan KL, Lucassen AM, Bunyan D, Temple IK (2007) Cowden syndrome and Bannayan Riley Ruvalcaba syndrome represent one condition with variable expression and age-related penetrance: results of a clinical study of PTEN mutation carriers. J Med Genet. 44(9):579–585 Epub 2007 May 25

Varga EA, Pastore M, Prior T, Herman GE, McBride KL. The prevalence of PTEN mutations in a clinical pediatric cohort with autism spectrum disorders. Developmental delay, and macrocephaly. Genet Med 2009;11 (2):111-7. Doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e31818fd762. PMID: 19265751

Hobert JA, Embacher R, Mester JL, Frazier 2nd TW, Eng C. Biochemical screening and PTEN mutation analysis in individuals with autism spectrum disorders and macrocephaly. Eur J Hum Genet 2014;22(2):273-6. Doi:10.1038/ejhg.2013.114.Epub 2013 May 22. PMID:23695273. PMCID: PMC3895634

Butler MG, Dasouki MJ, Zhou X-p, Talebizadeh T, Brown M, Takahashi TN, Miles JH, Wang CH, Stratton R, Pilarski R, Eng C. Subset of individuals with autism spectrum disorders and extreme macrocephaly associated with germline PTEN tumour suppressor gene mutations. J Med Genet. 200542 (4):318-21. Doi: 20.2236/jmg.2004.024646. PMID: 15805158. PMCID: PMC1736032

Eng C (1993) PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA et al (eds) GeneReviews((R)). University of Washington, Seattle

Buxbaum JD, Cai G, Chaste P, Nygren G, Goldsmith J, Reichert J, et al. Mutation screening of the PTEN gene in patients with autism spectrum disorders and macrocephaly. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. (2007) 144b:484–91. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30493

Bubien V, Bonnet F, Brouste V, Hoppe S, Barouk-Simonet E, David A, Edery P, Bottani A, Layet V, Caron O, Gilbert-Dussardier B, Delnatte C, Dugast C, Fricker JP, Bonneau D, Sevenet N, Longy M, Caux F; French Cowden Disease Network. High cumulative risks of cancer in patients with PTEN hamartoma tumour syndrome. J Med Genet. 2013;50(4):255-263. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101339. Epub 2013 Jan 18.

Tan MH, Mester JL, Ngeow J, Rybicki LA, Orloff MS, Eng C (2012) Lifetime cancer risks in individuals with germline PTEN mutations. Clin Cancer Res. 18(2):400–407. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2283

Plamper M, Born M, Gohlke B, Schreiner F, Schulte S, Splittstößer V, Woelfle J. Cerebral MRI and clinical findings in children with PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: can cerebral MRI scan help to establish an earlier diagnosis of PHTS in children? Cells 2020;9(7):1668. Doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9071668. PMID 32664367

Busch RM, Chapin JS, Mester J, Fergueson L, Haut JS, Frazier TW, Eng C (2013) The cognitive characteristics of PTEN hamartoma tumor syndromes. Genet Med. 15(7):548–553. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2013.1

Tan, M.H.; Mester J; Peterson C; Yang Y; Chen, J.L.; Rybicki, L.A.; Milas, K; Pederson, H; Remzi, B; Orloff, M.S.; Eng, C. A clinical scoring system for selection of patients for PTEN mutation testing is proposed on the basis of a prospective study of 3042 probands. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88(1):42-56. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.11.013. Epub 2010 Dec 30

Busch RM, Strivasta S, Hogue O, Frazier TW, Klaas P, Hardan A, Martinez-Agosto JA, Sahin M, Eng C (2019) Developmental synaptopathies consortium, neurobehavioral phenotype of 17 autism spectrum disorder associated with germline heterozygous mutations in PTEN. Transl Psychiatry. 9(1):253

Meng-Chuan Lai, Michael V Lomardo, Simon Baron-Cohen. Autism. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):896-910. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)61539-1. Epub 2013 Sep 26.

Riegert-Johnson DL, Gleeson FC, Roberts M, Tholen K, Youngborg L, Bullock M, Boardman LA (2010) Cancer and Lhermitte-Duclos disease are common in Cowden syndrome patients. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 8(1):6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1897-4287-8-6

Mirinae Seo, Nariya Cho, Hye Shin Ahn and Hyeong-Gon Moon. Cowden Syndrome presenting as breast cancer: imaging and clinicial features. Korean J Radiol. 2014t;15(5):586-590. Published online Sep 12, 2014. https://doi.org/10.3348/kjr.2014.15.5.586

Ngeow J, Sesock K, Eng C. Breast cancer risk and clinical implications for germline PTEN mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;165(1):1-8. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-015-3665-z. Epub 2015 Dec 23. PMID:26700035

Fackenthal JD, Marsh DJ, Richardson AL, Cummings SA, Eng C, Robinson BG, Olopade OI (2001) Male breast cancer in Cowden syndrome patients with germline PTEN mutations. J Med Genet 38:159–164

Hagelstrom RT, Ford J, Reiser GM, Nelson M, Pickering DL, Althof PA, Sanger WG, Coccia PF (2016) Breast cancer and non-Hodgkin lymphoma in a young male with Cowden syndrome. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 63(3):544–546. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.25796 Epub 2015 Oct 15

Pilarski R (2009) Cowden syndrome: a critical review of the clinical literature. J Genet Couns. 18(1):13–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-008-9187-7 Epub 2008 Oct 30

Hall JE, Abdollahian DJ, Sinard RJ (2013) Thyroid disease associated with Cowden syndrome: a meta-analysis. Head Neck. 35(8):1189–1194. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.22971 Epub 2012 Mar 20

Clement SC, Kremer LC, Links TP, Mulder RL, Ronckers CM, van Eck-Smit BL, van Rijn RR, van der Pal HJ, Tissing WJ, Janssens GO, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Neggers SJ, van Dijkum EJ, Peeters RP, van Santen HM. Is outcome of differentiated thyroid carcinoma influenced by tumor stage at diagnosis? Cancer Treat Rev. 2015;41(1):9-16. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2014.10.009. Epub 2014 Nov 11. PMID: 25544598.

Jonker LA, Lebbink CA, Jongmans MCJ, Nievelstein RAJ, Merks JHM, Nieveen van Dijkum EJM, Links TP, Hoogerbrugge N, van Trotsenbrug ASP, van Santen HM. Recommendation on surveillance for differentiated thyroid carcinoma in children with PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome. Eur Thyroid J. 2020;9(5):234-242. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1150/000508872.Epub 2020 Jul 28

Smith JR, Liu E, Church AJ, Asch E, Cherella CE, Srivastava S, Kamihara J, Wassner AJ. Natural history of thyroid disease in children with PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome, JCEM, Vol. 106, Issue 3, 2021, Pages e1121-e1130, https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgaa944

Tuli G, Munarin J, Mussa A, Carli D, Gastaldi R, Borgia P, Vigone MC, Abbate M, Ferrero GB, De Sanctis L. Thyroid nodular disease and PTEN mutation in a multicentre series of children with PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome (PHTS). Endocrine (2021) 74:632-636. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020.021-02805-y.

Ngeow J, Mester J, Rybicki LA, Ni Y, Milas M, Eng C (2011) Incidence and clinical characteristics of thyroid cancer in prospective series of individuals with Cowden and Cowden-like syndrome characterized by germline PTEN, SDH, or KLLN alterations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96(12):E2063–E2071

Harach HR, Soubeyran I, Brown A, Bonneau D, Longy M (1999) Thyroid pathologic findings in patients with Cowden disease. Ann Diagn Pathol 3(6):331–340

Milas M, Mester J, Metzger R, Shin J, Mitchell J, Berber E, Siperstein AE, Eng C (2012) Should patients with Cowden syndrome undergo prophylactic thyroidectomy? Surgery 152(6):1201–1210

Heald B, Mester J, Rybicki L, Orloff MS, Burke CA, Eng C (2010) Frequent gastrointestinal polyps and colorectal adenocarcinomas in a prospective series of PTEN mutation carriers. Gastroenterology. 139:1927–1933

Stanich PP, Owens VL, Sweetser S, Khambatta S, Smyrk TC, Richardson RL, Goetz MP, Patnaik MM. Colonic polyposis and neoplasia in Cowden syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc.2011; 86:489-492 [PubMed:21628613]

Syngal S, Brand RE, Church JM, Giardiello FM, Hampel HL, Burt, RW. American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guideline: genetic testing and management of hereditary gastrointestinal cancer syndromes. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015; 110(2): 223-62. Doi:10.1038/ajg.2014.435. Epub 2015 Feb 3. PMID: 25645574. PMCID: PMC4695986.

McGarrity TJ, Wagner Baker MJ, Ruggiero FM, Thiboutot DM, Hampel H, Zhou XP, Eng C (2003) GI polyposis and glycogenic acanthosis of the esophagus associated with PTEN mutation positive Cowden syndrome in the absence of cutaneous manifestations. Am J Gastroenterol. 98:1429–1434

Henderson CJ, Ngeow J, Collins MH, Martin LJ, Putnam PE, Abonia JP, Marsolo K, Eng C, Rothenberg ME (2014) Increased prevalence of eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders in pediatric PTEN hamartoma tumor syndromes. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 58(5):553–560. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0000000000000253

Koichi Inukai , Nobuhiro Takashima , Shiro Fujihata , Hirotaka Miyai , Minoru Yamamoto , Kenji Kobayashi , Moritsugu Tanaka and Tetsushi Hayakawa. Arteriovenous malformation in the sigmoid colon of a patient with Cowden disease treated with laparoscopy: a case report. BMC Surgery 2018 18:21 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-018-0355-x

Heald B, Burke CA, Kalady M, Eng C (2015) ACG guidelines on management of PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: does the evidence support so much so young? Am J Gastroenterol. 110(12):1733–1734. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2015.368

Tan W-H, Baris HN, Burrows PE, Robson CD, Alomari AI, Mulliken JB, Fishman SJ, Irons MB. The spectrum of vascular anomalies in patients with PTEN mutations: implications for diagnosis and management. J Med Genet 2007;44:594-602. Doi 0.1136/jmg.2007.048934

Turnbull MM, Humeniuk V, Stein B, Suthers GK (2005) Arteriovenous malformations in Cowden syndrome. J Med Genet. 42:e50

Jenny B, Radovanovic I, Haenggeli CA, Delavelle J, Rüfenacht D, Kaelin A, Blouin JL, Bottani A, Rilliet B (2007) Association of multiple vertebral hemangiomas and severe paraparesis in a patient with a PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome. Case report. J Neurosurg. 107(4 Suppl):307–313

Nakayama Y, Segawa J, Sujita K, Minagawa N, Torigoe T, Hisaoka M et al (2013) Intestinal bleeding from arteriovenous malformations of the small bowel in a patient with Cowden syndrome: report of a case. Surg Today. 43:542–546

Takaya N, Iwase T, Maehara A, Nishiyama S, Nakanishi S, Yamana D, Takei R, Kokubo T, Kohtake H, Furui S, Tomoyasu H, Seki A (1999) Transcatheter embolization of arteriovenous malformations in Cowden disease. Jpn Circ J 63:326–329

Chen HH, Händel N, Ngeow J, Muller J, Hühn M, Yang HT, Heindl M, Berbers RM, Hegazy AN, Kionke J, Yehia L, Sack U, Bläser F, Rensing-Ehl A, Reifenberger J, Keith J, Travis S, Merkenschlager A, Kiess W, Wittekind C, Walker L, Ehl S, Aretz S, Dustin ML, Eng C, Powrie F, Uhlig HH. Immune dysregulation in patients with PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: analysis of FOXP3 regulatory T cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(2):607-620.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.03.059. Epub 2016 Jun 18

Heindl M, Händel N, Ngeow J, Kionke J, Wittekind C, Kamprad M, Rensing-Ehl A, Ehl S, Reifenberger J, Loddenkemper C, Maul J, Hoffmeister A, Aretz S, Kiess W, Eng C, Uhlig HH. Autoimmunity, intestinal lymphoid hyperplasia, and defects in mucosal B-cell homeostasis in patients with PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(5):1093-1096.e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.01.011. Epub 2012 Jan 20.

Pal A, Barber TM, Van de Bunt M, Rudge SA, Zhang Q, Lachlan KL, Cooper NS, Linden H, Levy JC, Wakelam MJ, Walker L, Karpe F, Gloyn AL. PTEN mutations as a cause of constitutive insulin sensitivity and obesity. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(11):1002-11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113966. PMID: 22970944; PMCID: PMC4072504.

Granados A, Eng C, Diaz A (2013) Brothers with germline PTEN mutations and persistent hypoglycemia, macrocephaly, developmental delay, short stature, and coagulopathy. J Pediatric Endocrinol Metabolism 26(1-2):137–141 https://doi.org/10.1515/jpem-2012-0227

Liu J, Ding G, Zou K, Jiang Z, Zhang J, Lu Y, Pignata A, Venner E, Liu P, Liu Z, Wangler MF, Sun Z. Genome sequencing analysis of a family with a child displaying severe abdominal distention and recurrent hypoglycemia. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2020;8(3):e1130. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.1130. Epub 2020 Jan 23. PMID: 31971667; PMCID: PMC7057095.

Şıklar Z, Çetin T, Çakar N, Berberoğlu M. The effectiveness of sirolimus treatment in two rare disorders with nonketotic hypoinsulinemic hypoglycemia: the role of mTOR pathway. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2020;12(4):439-443. doi: 10.4274/jcrpe.galenos.2020.2019.0084. Epub 2020 Mar 11. PMID: 32157856; PMCID: PMC7711646.

Neuhauser, H.; Schienkiewitz, A.; Schaffrath Rosario, A.; Dortschy, R.; Kurth, B.M. Referenzperzentilen für anthropometrische Maßzahlen und Blutdruck aus der Studie zur Gesundheit von Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland (KiGGS). In Beiträge zur Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes, 2nd ed.; Robert Koch Institut: Berlin, Gemany, 2013; ISBM 978-3-89606-218-5.

Pilarski R, Burt R, Kohlman W, Pho L, Shannon KM, Swisher E. Cowden syndrome and the PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: systematic review and revised diagnostic criteria. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(21):1607-1616. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djt277. Epub 2013 Oct 17. Review

Plamper M, Aretz S, Buderus S, Kionke J, Schneider D, Kraegeloh-Mann I, Woelfle J. AWMF Leitlinie: Diagnostik und Management von Patienten mit PTEN Hamartom Tumor Syndrom (PHTS) im Kindes- und Jugendalter. https://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/174- 025.htm

Marsh DJ, Trahair TN, Martin JL, Chee WY, Walker J, Kirk EP, Baxter RC, Marshall GM (2008) Rapamycin treatment for a child with germline PTEN mutation. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 5(6):357–361

Lacobas I, Burrows PE, Adams DM, Sutton VR, Hollier LH, Chintagumpala MM (2011) Oral rapamycin in the treatment of patients with hamartoma syndromes and PTEN mutation. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 57(2):321–323

Schmid GL, Kässner F, Uhlig HH, Körner A, Kratzsch J, Händel N, Zepp FP, Kowalzik F, Laner A, Starke S, Wilhelm FK, Schuster S, Viehweger A, Hirsch W, Kiess W, Garten A (2014) Sirolimus treatment of severe PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: case report and in vitro studies. Pediatr Res. 75(4):527–534. https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2013.246 Epub 2013 Dec 23

Keppler-Noreuil KM, Parker VE, Darling TN, Martinez-Agosto JA (2016) Somatic overgrowth disorders of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway & therapeutic strategies. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 172(4):402–421. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.c.31531 Epub 2016 Nov 18

Acknowledgments

We thank Kinderkrankenhaus Kliniken der Stadt Köln by courtesy of the cerebral MRI picture (Fig. 1) and PD Dr. Mark Born for providing the ultrasound pictures. We thank all patients and families and the German patient support group for their support.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MP masterminded the German pediatric guideline for PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome in childhood and adolescence and wrote the manuscript. JW masterminded the creation of the German pediatric guideline for PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome in childhood and adolescence and rewrote the manuscript. BG rewrote the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

We obtained the consent to publish figures (Fig. 2) from the patient’s parents.

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Competing interests

None

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Plamper, M., Gohlke, B. & Woelfle, J. PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome in childhood and adolescence—a comprehensive review and presentation of the German pediatric guideline. Mol Cell Pediatr 9, 3 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40348-022-00135-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40348-022-00135-1