Abstract

Background

Factors associated with suicide attempts during the antecedent illness trajectory of bipolar disorder (BD) and schizophrenia (SZ) are poorly understood.

Methods

Utilizing the Rochester Epidemiology Project, individuals born after 1985 in Olmsted County, MN, presented with first episode mania (FEM) or psychosis (FEP), subsequently diagnosed with BD or SZ were identified. Patient demographics, suicidal ideation with plan, self-harm, suicide attempts, psychiatric hospitalizations, substance use, and childhood adversities were quantified using the electronic health record. Analyses pooled BD and SZ groups with a transdiagnostic approach given the two diseases were not yet differentiated. Factors associated with suicide attempts were examined using bivariate methods and multivariable logistic regression modeling.

Results

A total of 205 individuals with FEM or FEP (BD = 74, SZ = 131) were included. Suicide attempts were identified in 39 (19%) patients. Those with suicide attempts during antecedent illness trajectory were more likely to be female, victims of domestic violence or bullying behavior, and have higher rates of psychiatric hospitalizations, suicidal ideation with plan and/or self-harm, as well as alcohol, drug, and nicotine use before FEM/FEP onset. Based on multivariable logistic regression, three factors remained independently associated with suicidal attempts: psychiatric hospitalization (OR = 5.84, 95% CI 2.09–16.33, p < 0.001), self-harm (OR = 3.46, 95% CI 1.29–9.30, p = 0.014), and nicotine use (OR = 3.02, 95% CI 1.17–7.76, p = 0.022).

Conclusion

Suicidal attempts were prevalent during the antecedents of BD and SZ and were associated with several risk factors before FEM/FEP. Their clinical recognition could contribute to improve early prediction and prevention of suicide during the antecedent illness trajectory of BD and SZ.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Suicide is a multifaceted global public health concern that leads to more than 700,000 deaths/year [WHO 2021]. Psychological autopsy studies in high-income countries revealed that at least 90% of people who die of suicide had a mental disorder at the time of death [Cavanagh et al. 2003; Hawton and van Heeringen 2009; Phillips 2010]. Additionally, two-thirds of persons who died from suicide had mental health care contacts, both primary and specialty outpatient care, the year before death [Schaffer et al. 2016]. However, risk prediction of suicide is challenging, owing to the low base rate of suicide, weakness of existing suicide prediction tools and their low predictive validity, especially for suicide mortality, and lack of evidence that targeted clinical interventions are effective in preventing suicide completion [Goldney 2000; Belsher et al. 2019; Kessler et al. 2020]. In this context, a prior history of suicide attempt is considered one of the most robust predictors of an eventual completed suicide [Gibb et al. 2005; Christiansen and Jensen 2007]. A previous observational cohort study using the Rochester Epidemiology Project (N = 1490 suicide attempters) supported that suicide attempts had a greater lethal risk than previously thought with approximately 60% of individuals who completed suicide died on their index attempts, and with more than 80% of subsequent completed suicides occurring within a year of the initial attempt [Bostwick et al. 2016].

Among subjects with severe mental illness, individuals with bipolar disorder (BD) and schizophrenia (SZ) have higher rates of suicidal behavior when compared to the general population. Specifically, the estimated pooled lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts was 26.8% (95% CI 22.1–31.9%) for individuals with SZ [Lu et al. 2019] and 33.9% (95% CI 31.3–36.6%) for those with BD [Dong et al. 2019]. Moreover, suicidality has been reported as a prevalent dimension in the prodromal phase of BD [Correll et al. 2007, 2014], SZ [Andriopoulos et al. 2011], and in those at clinical high-risk for psychosis [Haining et al. 2021]. Although the phenotypical overlap between the psychiatric antecedents in these disorders calls for a simultaneous investigation into both illness trajectories [Léger et al. 2022]. For example, only a few studies have analyzed the degree of suicidal behavior between patients with BD and SZ prior to syndromal expression of BD and SZ [Kafali et al. 2019; Léger et al. 2022; Verdolini et al. 2022] without specifically investigating factors associated with suicide attempts. However, it is crucial to prioritize future research efforts in identifying populations at risk for initial suicidal attempts due to the significant lethality associated with them [Bostwick et al. 2016]. To the best of our knowledge, no previous study used a transdiagnostic approach for investigating suicidality in the antecedent illness trajectory of BD and SZ.

In our previous community-based epidemiological cohort study, we reported similar duration of psychiatric antecedents for BD (7.39 ± 6 years) and SZ (8.2 ± 6 years) suggesting similar but non-identical illness trajectories before the first episode mania (FEM) and first episode psychosis (FEP) [Ortiz-Orendain et al. 2023], as it has been previously suggested [Correll et al. 2007; Olvet et al. 2010]. Indeed, the few studies that have compared the antecedents of SZ and BD have found a significant overlap in the illness trajectory prior to FEM/FEP, revealing striking resemblances between these two conditions in clinical features, including symptom profile, premorbid adjustment, prescribed medications, substances used, and historical diagnoses [Correll et al. 2007; Olvet et al. 2010; Rietdijk et al. 2011; Chan et al. 2019; Kafali et al. 2019; Verdolini et al. 2022], with some authors suggesting that the antecedents between these two disorders are “indistinguishable” [Olvet et al. 2010]. Furthermore, a growing body of literature suggests that BD and SZ share commonalities across multiple domains, including genetic risk [Lichtenstein et al. 2009; Mullins et al. 2021], neuroimaging correlates [Dobri et al. 2022; Rootes-Murdy et al. 2022; Koen et al. 2023], and cognitive profiles [Pradhan et al. 2008; Olvet et al. 2010; Jiménez-López et al. 2017]. Such evidence supports that SZ and BD lie along a spectrum that argues for a dimensional approach to inform preventive strategies, particularly in the illness trajectory prior to full-blown diagnostic presentation of these disorders.

In this study, we aimed to investigate the prevalence and factors associated with suicide attempts during the illness trajectory between the onset of first symptoms and the full development of a FEM or FEP.

Methods

Search strategy

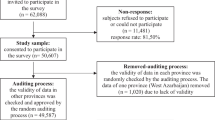

All residents from Olmsted County, MN USA born after 1985 and diagnosed with BD or SZ were identified using the Rochester Epidemiology project (REP). The REP is a population-based registry that allows to retrospectively analyze the history of individuals who developed an illness while mitigating risks of sampling, recall, referral, and response biases [Allebeck et al. 2009; Maret-Ouda et al. 2017]. The REP contains sociodemographic and clinical information of all residents of Olmsted County who had received treatment from 1986 onwards and has shown its validity in previous studies both for BD and SZ [Capasso et al. 2008; Prieto et al. 2016; Gardea-Resendez et al. 2023; Ortiz-Orendain et al. 2023].

A detailed description of the search strategy and case ascertainment has been extensively described in a previous report conducted by our group [Ortiz-Orendain et al. 2023]. After conducting an initial screening phase that involved utilizing diagnostic codes and systematically evaluating the health records of 1335 patients for DSM-5 criteria of BD and SZ as determined by two psychiatrists (authors JOO or MGR), we proceeded to search for FEM or FEP as described by Breitborde et al. (2009) [Breitborde et al. 2009]. Any disagreements regarding case ascertainment were resolved by consulting a panel consisting of three senior psychiatrists (AMc, AO, and MAF).

Population

Once we identified the SZ and BD cases with FEP or FEM, patients’ demographics, first-episode data, and psychiatric history prior to FEM/FEP were extracted using a standardized version to collect data created with RedCap [Harris et al. 2019]. Codes for mental health disorders were classified according to the spectrums of DSM-5 [APA 2013]. Specifically, we collected data for the following variables: suicidal ideation with plan, self-harm, suicide attempts, psychiatric hospitalizations, alcohol and substance use, previous childhood adversities, and psychiatric diagnosis during the illness trajectory before FEM/FEP. A full description of the other extracted variables has been thoroughly documented in recent reports carried out by our group [Gardea-Resendez et al. 2023; Ortiz-Orendain et al. 2023]. Considering the lack of consensus on the operationalization of the prodrome phase [Geoffroy et al. 2017; Kupka et al. 2021], the psychiatric antecedent onset was defined as the date in which the first psychiatric symptoms, including neurodevelopmental disorders, was first coded in the patients’ health record or the first time a mental health problem was reported in the problem list of a clinical note [Ortiz-Orendain et al. 2023]. The first episode was defined as the clinical encounter during which an individual was first noted to exhibit symptoms of psychosis or mania [Breitborde et al. 2009]. For this study, a suicide attempt was defined as a self-injurious behavior with the intention to die, whereas self-harm with no suicidal intention was reported as a separate outcome, as it has been previously done in other investigations [Verdolini et al. 2022].

The current retrospective population-based study was approved by the institutional review boards (IRBs) of Mayo Clinic (IRB # 20–006720 and 20–008773) and Olmsted Medical Center (Approval dates: 11/20/2020 and 04/22/2021) who provided a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) waiver, in line with state, federal, and international recommendations. Hence, written informed consent was not required for passive medical record review in the REP [Rocca et al. 2018].

Statistical analysis

Prodromal analyses pooled BD and SZ groups, given the two diseases were not yet differentiated prior to the full development of a FEM or FEP and the evidence of phenotypical overlap between the antecedent illness trajectory in these disorders [Correll et al. 2007; Olvet et al. 2010; Léger et al. 2022]. Sociodemographic and selected clinical data associated with suicide attempts were compared between subjects with versus without at least one suicide attempt using chi-square tests (χ2) for categorical measures and analysis of variance (two-sample t-tests) for continuous measures. Due to the high correlation between the aforementioned variables, we used a multivariate logistic regression model to identify factors that were independently associated with suicide attempts. However, because of the limited sample size of the study, we could not include all variables into one model. Instead, we tested several multivariate logistic regression models using a forward–backward stepwise approach for variable selection. Given the known strong relationship between certain variables such as suicide attempts and psychiatric hospitalizations and self-harming behavior [Verdoux et al. 2001; Goldstein et al. 2005; Robinson et al. 2010; Beckman et al. 2016; Olfson et al. 2016], we also repeated this stepwise approach while omitting these variables from the selection procedure. Model performance was then compared and the two models (with and without previous hospitalization, self-harm and ideation included) with the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC)—which favors more parsimonious models—were selected [Hosmer et al. 2013]. Odds ratios (OR) with confidence intervals (CI) were used as a measure of effect size. Statistical analyses were performed using Jamovi (https://www.jamovi.org/).

Results

Participants characteristics

This study included 205 patients who met diagnostic criteria for a DSM-5 SZ (N = 131) and BD (N = 74) with FEP or FEM. Of the 205-study sample, 28 (13.7%) experienced suicidal ideation with plan, 41 (20.0%) had a previous self-harm behavior, and 39 (19%) attempted suicide during the illness trajectory prior to FEM or FEP (Table 1).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of 205 patients with and without suicide attempts during the illness trajectory before FEM/FEP are compared in Table 2.

Those with suicide attempt did not significantly differ in terms of diagnosis (BD = 22.97% and SZ = 16.79%, respectively, p = 0.279) nor the age of first episode when compared with those who did not experience any suicide attempt (21.7 vs. 20.5 years, p = 0.146). When compared with patients who did not attempt suicide, those with suicide attempts were more likely to be women (22.9 vs. 43.6%, respectively, p = 0.009) and had higher rates of psychiatric hospitalizations during the illness trajectory before FEM/FEP (12 vs. 61.5%, p < 0.001). As expected, those that attempted suicide were more likely to experience suicidal ideation with plan (41 vs. 7.2%, p < 0.001) and exhibited higher rates of self-harm during the illness trajectory before FEP/FEM when compared to those who did not (53.8 vs. 12%, p < 0.001). Additionally, those with suicide attempts were more likely to have had witnessed domestic violence (41 vs. 19.3%, p = 0.004) and be victims of bullying behavior (17.9 vs. 5.4%, p = 0.009). Patients attempting suicide during the illness trajectory before FEM/FEP displayed higher rates of depressive disorders (79.5 vs. 47%, p < 0.001), anxiety disorders (56.4 vs. 30.7%, p = 0.003), and adjustment disorders (41 vs. 22.9%, p = 0.021), along with sleep disorders (23.1 vs. 9.6%, p = 0.021), disordered eating behaviors (10.3 vs. 3%, p = 0.047) and personality disorders (15.4 vs. 6%, p = 0.05) when compared to those who did not. Lastly, those with suicide attempts were more likely to use nicotine (64.1 vs. 31.9%, p < 0.001), alcohol (64.1 vs. 41%, p = 0.009), methamphetamines (30.8 vs. 12.7%, p = 0.006), cocaine (17.9 vs. 7.2%, p = 0.038), and to abuse hypnotics, benzodiazepines, and barbiturates (20.5 vs. 6%, p = 0.004) in comparison to those who did not attempt suicide before FEM/FEP.

Multivariable modeling

We first ran our stepwise approach using all of the variables included in Table 2. The best model included three factors which were all independently associated with suicidal attempts during the illness trajectory before FEM/FEP: [a] psychiatric hospitalizations (OR = 5.84, 95% CI 2.09–16.33, p < 0.001), [b] self-harming behavior (OR = 3.46, 95% CI 1.29–9.30, p = 0.014), [c] nicotine use (OR = 3.02, 95% CI 1.17–7.76, p = 0.022) (Table 3). The variance explained by the model was 39% (Nagelkerke R-Squared = 0.390, AIC = 135).

Because factors such as previous hospitalization, self-harming behavior, and suicidal ideation are well-known risk factors for future attempts [Beckman et al. 2016; Olfson et al. 2016], we also investigated a model which excluded these factors to determine if other variables could also be associated with suicide attempt during the illness trajectory before FEM/FEP. In this second stepwise procedure, the best model retained four factors all of which were also independently associated with suicidal attempts: [a] female sex (OR = 3.09, 95% CI 1.29–7.39, p = 0.011), [b] depressive disorder diagnosis (OR = 2.71, 95% CI 1.10–6.69, p = 0.030), [c] nicotine use (OR = 4.78, 95% CI 1.98–11.54, p < 0.001), [d] bullying (OR = 5.09, 95% CI 1.44–18.00, p = 0.012) (Table 4). This model did not perform as well as the model using known factors for suicide attempts but still explained 28% of the variance (Nagelkerke R-Squared = 0.283, AIC = 172).

Discussion

This community-based epidemiological cohort study which included 205 subjects who met DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for SZ (N = 131) and BD (N = 74) aimed to investigate transdiagnostically the frequency of suicide attempts as well as to identify sociodemographic and clinical features associated with suicide attempts during the illness trajectory prior to a FEM/FEP.

Our findings revealed that one fifth (N = 39, 19%) of patients attempted suicide during the illness trajectory before FEM/FEP, while suicidal ideation with plan was found in 13.7% (N = 28) and self-harming behaviors in 20% (N = 41) of the patients studied. There were no significant differences in suicidality between the two diagnoses (BD vs. SZ), which is in accordance with recent reports [Lèger et al. 2022; Verdolini et al. 2022].

Although a broad range of factors were associated with suicide attempts before FEM/FEP in the univariate logistic regression models (Table 2), female sex, psychiatric hospitalizations, self-harming behavior, depressive disorders, nicotine use, and being the victims of bully behavior were found to be independently associated with suicide attempts in the multivariable models. Our work is in accordance with earlier research that examined suicide risk factors in major affective disorders (MDD and BD) identifying a greater number of hospitalizations for depression and early abuse and trauma [Baldessarini et al. 2019; Miola et al. 2023]. In addition, large epidemiological studies in the US have reported that bullying behavior was associated with an increase frequency of suicide ideation, plan and attempts in children [Kim et al. 2008] which emphasizes the need to carefully monitor, and tailor targeted early interventions in this population. As expected, previous or current depressive symptoms have been associated with suicide attempts both in patients with FEM [Khalsa et al. 2008] and FEP [Barrett et al. 2010; Andriopoulos et al. 2011; Sanchez-Gistau et al. 2013]. Moreover, our findings of higher rates of psychiatric hospitalization and non-suicidal self-injurious behavior in those who attempted suicide are consistent with previous reports which focused on youth with BD [Goldstein et al. 2005, 2012] and FEP [Verdoux et al. 2001; Robinson et al. 2010].

There has been ample literature that has shown an association between substance use and higher prevalence of suicide attempts in affective disorders [Tondo et al. 1999; Miola et al. 2023] and SZ [Fuller-Thomson and Hollister 2016]. Interestingly, our study has shown a higher association with nicotine, alcohol, meta-amphetamines, cocaine and abuse of hypnotics, benzodiazepines, and barbiturates in the illness trajectory before FEM/FEP. The high prevalence and bidirectional association between suicide attempts and substance use has also been suggested in previous studies. For example, a Swedish population study of 13,352 men and 5542 women examined death caused by suicide and highlighted that alcohol, cannabis, and central stimulants were associated with higher violent methods of suicide [Lundholm et al. 2014]; all these underscoring the need to carefully review patients use or abuse of substances as well as accessibility to weapons. Similarly, in a Danish register-based cohort study analyzing data from people diagnosed with SZ (n = 35,625), BD (n = 9279), depression (n = 72,530), or personality disorder (n = 63,958), having any substance use disorder was associated with at least a threefold increased risk of completed suicide compared with those without substance use disorder [Østergaard et al. 2017]. Of note, our findings underscoring the association of nicotine use and suicide attempts during psychiatric antecedents before FEM/FEP (significant for in both multivariable logistic regression models), even after controlling for well-known confounding factors including female sex, previous childhood adversities, depressive disorders, and co-occurring alcohol and substance use [Tomori et al. 2001], is in accordance with a study by Andriopoulus and colleagues [Andriopoulus et al. 2011]. As also seen in the current study, the latter report emphasized that tobacco smoking and depressive mood were associated with prodromal suicide attempts in patients with SZ [Andriopoulus et al. 2011]. Moreover, tobacco smoking has been reported as a potentially independent risk factor for suicide attempts in BD [Ostacher et al. 2009; Ducasse et al. 2015]. Interestingly, tobacco smoking, both alone and comorbid with alcohol use disorders, depressive polarity of BD onset, and female sex were independently associated with recurrent suicide attempts in a cohort of 916 patients with BD [Icick et al. 2019].

However, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations of the present study. First, the retrospective study design may introduce inherent limitations such as information bias and missing data, which may limit our ability to establish causality in the current findings. Nonetheless, previous REP studies have demonstrated validity and reliability, as evidenced by previous reports [Capasso et al. 2008; Prieto et al. 2016; Gardea-Resendez et al. 2023; Ortiz-Orendain et al. 2023]. Second, the REP demographics may limit the study’s generalizability due to a less diverse population (higher prevalence of white population), and of higher socioeconomic status [St Sauver et al. 2012]. Third, suicidal ideation was evaluated by clinicians without the use of standardized scales within the real-world clinical practice setting and was extracted from clinical notes of patients’ health records, which may have led to potential underreporting of such cases. Fourth, recognition of suicide attempts is more difficult than suicide because nonviolent attempts may not be reported, can easily be concealed, and may be considered accidents or nonvoluntary acts. As a result, reported rates of suicide attempts are at risk of misdiagnosis and underreporting [Bachmann 2018]. Nevertheless, the REP represents a unique database in the United States that permits population-based research with medical, and continuity of care data collected by healthcare professionals [St Sauver et al. 2012].

On the other hand, our study has some strengths such as the thorough case ascertainment by psychiatrists and the quality of the extracted data from clinical notes which can minimize the possibility of a recall bias.

In conclusion, our study brings to the forefront the need to further examine and carefully monitor for clinical risk factors during the illness trajectory before FEM/FEP. Larger studies with prospective longitudinal design may be needed to validate some of these findings as well as to quantify risk for suicidality in this vulnerable population as to tailor effective preventive measures.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

Allebeck P. The use of population based registers in psychiatric research. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;120(5):386–91.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Andriopoulos I, Ellul J, Skokou M, Beratis S. Suicidality in the “prodromal” phase of schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. 2011;52(5):479–85.

Bachmann S. Epidemiology of suicide and the psychiatric perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:1425–48.

Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Pinna M, Nuñez N, Vázquez GH. Suicidal risk factors in major affective disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2019;11:1–6.

Barrett EA, Sundet K, Faerden A, et al. Suicidality before and in the early phases of first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2010;119(1–3):11–7.

Beckman K, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Lichtenstein P, et al. Mental illness and suicide after self-harm among young adults: long-term follow-up of self-harm patients, admitted to hospital care, in a national cohort. Psychol Med. 2016;46(16):3397–405.

Belsher BE, Smolenski DJ, Pruitt LD, et al. Prediction models for suicide attempts and deaths: a systematic review and simulation. JAMA Psychiat. 2019;76(6):642–51.

Bostwick JM, Pabbati C, Geske JR, McKean AJ. Suicide attempt as a risk factor for completed suicide: even more lethal than we knew. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(11):1094–100.

Breitborde NJ, Srihari VH, Woods SW. Review of the operational definition for first-episode psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2009;3:259–65.

Capasso RM, Lineberry TW, Bostwick JM, Decker PA, St SJ. Mortality in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: an Olmsted County, Minnesota cohort: 1950–2005. Schizophr Res. 2008;98:287–94.

Cavanagh JTO, Carson AJ, Sharpe M, Lawrie SM. Psychological autopsy studies of suicide: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2003;33:395–405.

Chan CC, Shanahan M, Ospina LH, et al. Premorbid adjustment trajectories in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a transdiagnostic cluster analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2019;272:655–62.

Christiansen E, Jensen BF. Risk of repetition of suicide attempt, suicide or all deaths after an episode of attempted suicide: a register-based survival analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2007;41(3):257–65.

Correll CU, Penzner JB, Frederickson AM, et al. Differentiation in the preonset phases of schizophrenia and mood disorders: evidence in support of a bipolar mania prodrome. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:703–14.

Correll CU, Hauser M, Penzner JB, et al. Type and duration of subsyndromal symptoms in youth with bipolar I disorder prior to their first manic episode. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16:478–92.

Dobri ML, Diaz AP, Selvaraj S, et al. The limits between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: what do magnetic resonance findings tell us? Behav Sci. 2022;12:78.

Dong M, Lu L, Zhang L, et al. Prevalence of suicide attempts in bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2019;29:e63.

Ducasse D, Jaussent I, Guillaume S, et al. FondaMental advanced centers of expertise in bipolar disorders (FACE-BD) collaborators. Increased risk of suicide attempt in bipolar patients with severe tobacco dependence. J Affect Disord. 2015;183:113–8.

Fuller-Thomson E, Hollister B. Schizophrenia and suicide attempts: findings from a representative community-based Canadian sample. Schizophr Res Treat. 2016;2016:3165243.

Gardea-Resendez M, Ortiz-Orendain J, Miola A, et al. Racial differences in pathways to care preceding first episode mania or psychosis: a historical cohort prodromal study. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1241071.

Geoffroy PA, Scott J. Prodrome or risk syndrome: what’s in a name? Int J Bipolar Disord. 2017;5:7.

Gibb SJ, Beautrais AL, Fergusson DM. Mortality and further suicidal behaviour after an index suicide attempt: a 10-year study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39:95–100.

Goldney RD. Prediction of suicide and prediction of suicide and attempted suicide. In: Hawton K, Van Heeringen K, editors. The international handbook of suicide and attempted suicide suicide and attempted suicide. Chichester: Wiley; 2000.

Goldstein TR, Birmaher B, Axelson D, et al. History of suicide attempts in pediatric bipolar disorder: factors associated with increased risk. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7:525–35.

Goldstein TR, Ha W, Axelson DA, et al. Predictors of prospectively examined suicide attempts among youth with bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:1113–22.

Haining K, Karagiorgou O, Gajwani R, et al. Prevalence and predictors of suicidality and non-suicidal self-harm among individuals at clinical high-risk for psychosis: results from a community-recruited sample. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2021;15:1256–65.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. REDCap consortium. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208.

Hawton K, van Heeringen K. Suicide. Lancet. 2009;373:1372–81.

Hosmer DW Jr, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX. Applied logistic regression. 3rd ed. Hoboken: Wiley; 2013.

Icick R, Melle I, Etain B, et al. Tobacco smoking and other substance use disorders associated with recurrent suicide attempts in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2019;256:348–57.

Jiménez-López E, Aparicio AI, Sánchez-Morla EM, et al. Neurocognition in patients with psychotic and non-psychotic bipolar I disorder. A comparative study with individuals with schizophrenia. J Affect Disord. 2017;222:169–76.

Kafali HY, Bildik T, Bora E, Yuncu Z, Erermis HS. Distinguishing prodromal stage of bipolar disorder and early onset schizophrenia spectrum disorders during adolescence. Psychiatry Res. 2019;275:315–25.

Kessler RC, Bossarte RM, Luedtke A, Zaslavsky AM, Zubizarreta JR. Suicide prediction models: a critical review of recent research with recommendations for the way forward. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:168–79.

Khalsa HM, Salvatore P, Hennen J, Baethge C, Tohen M, Baldessarini RJ. Suicidal events and accidents in 216 first-episode bipolar I disorder patients: predictive factors. J Affect Disord. 2008;106:179–84.

Kim YS, Leventhal B. Bullying and suicide. A review. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2008;20:133–54.

Koen JD, Lewis L, Rugg MD, et al. Supervised machine learning classification of psychosis biotypes based on brain structure: findings from the bipolar-schizophrenia network for intermediate phenotypes (B-SNIP). Sci Rep. 2023;13:12980.

Kupka R, Duffy A, Scott J, et al. Consensus on nomenclature for clinical staging models in bipolar disorder: a narrative review from the international society for bipolar disorders (ISBD) staging task force. Bipolar Disord. 2021;23:659–78.

Léger M, Wolff V, Kabuth B, Albuisson E, Ligier F. The mood disorder spectrum vs. schizophrenia decision tree: EDIPHAS research into the childhood and adolescence of 205 patients. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22:194.

Lichtenstein P, Yip BH, Björk C, et al. Common genetic determinants of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in Swedish families: a population-based study. Lancet. 2009;373:234–9.

Lu L, Dong M, Zhang L, et al. Prevalence of suicide attempts in individuals with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2019;29:e39.

Lundholm L, Thiblin I, Runeson B, Leifman A, Fugelstad A. Acute influence of alcohol, THC or central stimulants on violent suicide: a Swedish population study. J Forensic Sci. 2014;59:436–40.

Maret-Ouda J, Tao W, Wahlin K, Lagergren J. Nordic registry-based cohort studies: possibilities and pitfalls when combining Nordic registry data. Scand J Public Health. 2017;45:14–9.

Miola A, Tondo L, Pinna M, et al. Suicidal risk and protective factors in major affective disorders: a prospective cohort study of 4307 participants. J Affect Disord. 2023;338:189–98.

Mullins N, Forstner AJ, O’Connell KS, et al. Genome-wide association study of more than 40,000 bipolar disorder cases provides new insights into the underlying biology. Nat Genet. 2021;53:817–29.

Olfson M, Wall M, Wang S, et al. Short-term suicide risk after psychiatric hospital discharge. JAMA Psychiat. 2016;73:1119–26.

Olvet DM, Stearns WH, McLaughlin D, Auther AM, Correll CU, Cornblatt BA. Comparing clinical and neurocognitive features of the schizophrenia prodrome to the bipolar prodrome. Schizophr Res. 2010;123:59–63.

Ortiz-Orendain J, Gardea-Resendez M, Castiello-de Obeso S, et al. Antecedents to first episode psychosis and mania: comparing the initial prodromes of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in a retrospective population cohort. J Affect Disord. 2023;340:25–32.

Ostacher MJ, Lebeau RT, Perlis RH, et al. Cigarette smoking is associated with suicidality in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11:766–71.

Østergaard MLD, Nordentoft M, Hjorthøj C. Associations between substance use disorders and suicide or suicide attempts in people with mental illness: a Danish nation-wide, prospective, register-based study of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, unipolar depression or personality disorder. Addiction. 2017;112:1250–9.

Phillips MR. Rethinking the role of mental illness in suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:731–3.

Pradhan BK, Chakrabarti S, Nehra R, et al. Cognitive functions in bipolar affective disorder and schizophrenia: comparison. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;62:515–25.

Prieto ML, Schenck LA, Kruse JL, et al. Long-term risk of myocardial infarction and stroke in bipolar I disorder: a population-based cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2016;194:120–7.

Rietdijk J, Hogerzeil SJ, van Hemert AM, et al. Pathways to psychosis: help-seeking behavior in the prodromal phase. Schizophr Res. 2011;132:213–9.

Robinson J, Harris MG, Harrigan SM, et al. Suicide attempt in first-episode psychosis: a 7.4 year follow-up study. Schizophr Res. 2010;116:1–8.

Rocca WA, Grossardt BR, Brue SM, et al. Data resource profile: expansion of the rochester epidemiology project medical records-linkage system (E-REP). Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47:368–368j.

Rootes-Murdy K, Edmond JT, Jiang W, et al. Clinical and cortical similarities identified between bipolar disorder I and schizophrenia: a multivariate approach. Front Hum Neurosci. 2022;16:1001692.

Sanchez-Gistau V, Baeza I, Arango C, et al. Predictors of suicide attempt in early-onset, first-episode psychoses: a longitudinal 24-month follow-up study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:59–66.

Schaffer A, Sinyor M, Kurdyak P, et al. Population-based analysis of health care contacts among suicide decedents: identifying opportunities for more targeted suicide prevention strategies. World Psychiatry. 2016;15:135–45.

St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Leibson CL, Yawn BP, Melton LJ 3rd, Rocca WA. Generalizability of epidemiological findings and public health decisions: an illustration from the rochester epidemiology project. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:151–60.

Tomori M, Zalar B, Kores Plesnicar B, Ziherl S, Stergar E. Smoking in relation to psychosocial risk factors in adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;10:143–50.

Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ, Hennen J, et al. Suicide attempts in major affective disorder patients with comorbid substance use disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(2):63–9.

Verdolini N, Borràs R, Sparacino G, et al. Prodromal phase: differences in prodromal symptoms, risk factors and markers of vulnerability in first episode mania versus first episode psychosis with onset in late adolescence or adulthood. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2022;146:36–50.

Verdoux H, Liraud F, Gonzales B, Assens F, Abalan F, van Os J. Predictors and outcome characteristics associated with suicidal behaviour in early psychosis: a two-year follow-up of first-admitted subjects. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;103:347–54.

World Health Organization. Suicide. 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported, in part, by the Luther Automotive Foundation and Mayo Foundation; neither had a role in the design, conduct, analysis, or submission of the study. This study was also made possible using the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project, which is supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AG034676. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Funding

This study was supported, in part, by the Luther Automotive Foundation and Mayo Foundation; neither had a role in the design, conduct, analysis, or submission of the study. This study was also made possible using the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project, which is supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AG034676. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AM organized the data, conducted the literature review, analyzed the data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MGR and JOO collected the data and revised the manuscript. NAN conducted the literature review, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MAF and AO wrote the first draft of the manuscript and revised the manuscript. BJC revised the data analysis and the manuscript. All authors contributed to the conception, design, and interpretation of data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The current retrospective population-based study was approved by the institutional review boards (IRBs) of Mayo Clinic (IRB # 20–006720 and 20–008773) and Olmsted Medical Center (Approval dates: 11/20/2020 and 04/22/2021) who provided a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) waiver, in line with state, federal, and international recommendations. Hence, written informed consent was not required for passive medical record review in the REP.

Competing interests

Mark A. Frye received grant support from Assurex Health and Mayo Foundation, received CME travel and honoraria from Carnot Laboratories, and has Financial Interest/Stock ownership/Royalties from Chymia LLC. No other declaration of interests from other authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Miola, A., Gardea-Reséndez, M., Ortiz-Orendain, J. et al. Factors associated with suicide attempts in the antecedent illness trajectory of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Int J Bipolar Disord 11, 38 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40345-023-00318-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40345-023-00318-3