Abstract

Background

The early detection of patients at risk of developing schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, and more broadly mood spectrum disorder, is a public health concern. The phenotypical overlap between the prodromes in these disorders calls for a simultaneous investigation into both illness trajectories.

Method

This is an epidemiological, retrospective, multicentre, descriptive study conducted in the Grand-Est region of France in order to describe and compare early symptoms in 205 patients: 123 of which were diagnosed with schizophrenia and 82 with bipolar disorder or mood spectrum disorder. Data corresponding to the pre-morbid and prodromal phases, including a timeline of their onset, were studied in child and adolescent psychiatric records via a data grid based on the literature review conducted from birth to 17 years of age.

Results

Two distinct trajectories were highlighted. Patients with schizophrenia tended to present more difficulties at each developmental stage, with the emergence of negative and positive behavioural symptoms during adolescence. Patients with mood spectrum disorder, however, were more likely to exhibit anxiety and then mood-related symptoms. Overall, our results corroborate current literature findings and are consistent with the neurodevelopmental process. We succeeded in extracting a decision tree with good predictability based on variables relating to one diagnosis: 77.6% of patients received a well-indexed diagnosis. An atypical profile was observed in future mood spectrum disorder patients as some exhibited numerous positive symptoms alongside more conventional mood-related symptoms.

Conclusion

The combination of all these data could help promote the early identification of high-risk patients thereby facilitating early prevention and appropriate intervention in order to improve outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The division of psychiatric disorders into “dementia praecox”, also known as schizophrenia, and “manisch-depressives Irresein” in German, now conceptualised as bipolar disorder, was first proposed by Emil Kraepelin in 1899. Both are severe, chronic, psychiatric disorders that remain significant public health concerns to this day. Taking the full spectrum of mood disorders into consideration, they affect up to 4.4% of the population and rank 4th in terms of global causes of morbidity and mortality among people under 25 years of age [1]. Schizophrenia affects between 0.3 and 0.7% of the global population [2]. Recovery is mostly partial but may become debilitating [3].

There remains a significant delay of approximately 10 years in the diagnosis of bipolar disorder [4]. Yet, we know that this condition can have devastating consequences if left untreated [5,6,7]. Schizophrenia is also a diagnosed late [8] and is linked to greater severity, poorer remission and a greater risk of relapse [9]. The efficacy of early intervention has been established with reduced transition towards psychosis [10, 11]. Consequently, the early detection of these conditions is a key objective.

In child and adolescent psychiatry, determining what the future holds for young patients presenting psychotic or mood-related symptoms can be a sensitive issue. A comprehensive understanding of the early signs and illness trajectories of schizophrenia and mood spectrum disorder is vital for personalised prevention and treatment strategies. Recent studies promote a neurodevelopmental model with a genetic overlap between both disorders [12], common risk factors [13] and shared cognitive impairment [14]. Nevertheless, additional factors adversely affecting neurodevelopment may impact patients with schizophrenia compared to those who go on to develop bipolar disorder [15, 16].

A prodromal phase has been identified in both pathologies, preceding the onset of the disorder per se by several months. An initial pre-morbid phase has also been described [1, 17]. These phases are now clearly defined in schizophrenia [18] using scales and questionnaires to identify individuals at high risk of psychosis [19]. Mood-related symptoms are also known to affect the development of bipolar disorders [20, 21]. However, these symptoms are not pathognomonic and the phenotypical overlap between the prodromes of schizophrenia and mood spectrum disorders requires simultaneous investigation of both illness trajectories.

It is interesting to compare these symptoms more precisely, focusing on connections and timing in relation to the onset of both disorders.

Methods

Objective

An objective study involves the construction of a decision tree to provide a descriptive, comparative analysis of the symptoms and a timeline of their onset during the childhood and adolescence of patients with schizophrenia or mood spectrum disorder.

Study design

This is an epidemiological, retrospective, multicentre, descriptive study conducted within the EDIPHAS (Dimensional Study of The Early Phases of Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia) research project framework [22]. Public psychiatric hospitals located in the Grand Est region of France served as recruitment centres for this study.

The eligibility criteria were as follows:

-

Adult psychiatric follow-up received between 2006 and 2017

-

Diagnosis of schizophrenia (F20) or mood spectrum disorder: F30 (manic episode), F31 (bipolar disorder), F33 (recurrent major depressive disorder), F34 (persistent mood disorder) according to ICD10

-

Between 18 and 30 years of age at the time of adult psychiatric follow-up

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

-

No previous childhood or adolescent psychiatric follow-up before the age of 18 and prior to diagnosis

-

Refusal to participate in the study.

Material

Adult psychiatric records were accessible only via computer software and were studied in order to establish the age at diagnosis. Data concerning childhood and adolescent symptoms were collected from the patients’ child and adolescent psychiatric medical records. They were stored in a data grid compiled following a literature review. This tool demonstrated satisfactory inter-rater reliability in previous EDIPHAS studies [22]. The patient’s age at time of onset was documented for each item. Symptoms were grouped according to clinical dimensions: cognitive/developmental, functional, anxiety-related, behavioural/impulse control, mood-related, negative and positive/discordant symptoms.

Population

Eligible study subjects were contacted by a letter sent either to their place of residence or to the then referring psychiatrist. This letter contained clearly set out the study objectives. It also stated that patients were entitled to refuse any requests to access or review their earlier medical records without their negative decision adversely impacting their treatment.

Analysis

Qualitative variables were represented in terms of both absolute number and population percentage. Quantitative variables were represented by average and standard deviation. The Mann-Whitney U-test, Chi2 or Fisher’s exact test were also applied depending on the nature and distribution of the variables. CHAID (Chi-squared Automatic Interaction Detection), which is a multivariate approach, was used to perform classification and segmentation analysis. The decision tree was constructed by repeatedly splitting a node (group) into two or more nodes, beginning with the entire data set. At each step, the predictor (covariable) that gives the best prediction is selected by the model and the node is split into two or more nodes based on the predictor values. SPSS has extended the algorithms to handle nominal, categorical, ordinal and continuous target variables. Chi square statistics were used to identify optimal splits. CHAID with crossed validation was used to build a decision tree with adult schizophrenia and mood spectrum disorder diagnoses as the outcome. We selected the covariables for the multivariable analysis (CHAID) based on significant results in univariate analysis, clinical reasoning and previous studies.

In the analysis, the level of significance was α=0.05.

IBM SPSS Statistics v22 software was used for the statistical analysis.

Results

General and clinical description of the population

Four hundred and fifty-three (453) adult patients were identified as eligible: 324 had been diagnosed with mood spectrum disorder (MSD) and 129 with schizophrenia (SZ). Among these patients, 242 did not have paediatric psychiatric records. Two sets of records did not contain information prior to diagnosis, 2 did not contain enough information for assessment and 2 patients declined to participate. Finally, 205 patients were enrolled in the study - 82 with MSD and 123 with SZ.

The SZ population mostly comprised males (67.5%) born during the winter (33.3%), while the MSD population consisted of mainly females (71.6%) born during the spring (40.2%). Only a few of the records contained detailed obstetric information. Foetal injury or neonatal complication was documented for 9.8% of SZ patients and 12.2% of MSD patients. In terms of family history, there was a high incidence of psychiatric illness amongst first degree relatives: 55.3% for SZ patients and 57.3% for MSD patients. In the majority of cases, the family history revealed mood disorders (39% in MSD and 25.2% in SZ) followed by psychosis (13.8% in SZ and 6.1% in MSD). A family history of suicide attempts was documented in 6.5% of the SZ population versus 0% of the MSD population. The average age of diagnosis was 20.6 years (Standard Deviation SD=3.9) in the SZ population and 20.9 years (SD=4.1) in the MSD population.

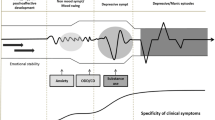

Some symptoms were presented by more than one-third of patients and tended to emerge in a particular sequence. Trajectory modelling appears to be an interesting approach for both populations in order to summarise the natural development of symptoms and the average age of onset. This information is presented in Figures 1 and 2.

Comparison of populations

Only one variable, namely the age of onset of “relational disturbances involving inhibition”, was not evenly distributed in both diagnostic categories (Mann-Whitney U test = 0.028).

Overall, 41 variables were significantly linked to diagnosis during independence tests (p<0.05). More symptoms were associated with the diagnosis of SZ than MSD. Detailed results according to each dimension are shown in Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4.

Decision tree

A decision tree based on symptoms significantly associated with each diagnosis has been extracted (Figure 3). The first node represents bizarre behaviours as a result of which the tree splits into multiple edges. There are six internal nodes before the leaves. The second level includes conduct disorders and sad mood while the third is based on mood swings, obsessional elements, thought disorders and educational underachievement.

This tool offers good predictability in our population as 77.6% of the patients received the correct diagnosis. 109 of the 123 diagnosed cases of schizophrenia, (88.6%) were clearly identified. Out of the 82 diagnoses of mood spectrum disorder, 50 (61%) were clearly identified. Therefore 14 cases of schizophrenia and 32 cases of mood spectrum disorder received the wrong predictive diagnosis.

CHAID (Chi-squared Automatic Interaction Detection) is a decision tree constructed by repeatedly splitting a node (group) into two nodes, beginning with the entire data set. At each step, the predictor (covariable) that gives the best prediction is selected and the node is split into two nodes based on the predictor values (0 absence or 1 presence). The best predictor for the entire data set is ‘Bizarre behaviours’ with adjusted p=0.0001. The next level includes ‘Conduct disorders’ with adjusted p=0.004 and ‘Sad Mood’ with adjusted p=0.0001. This is followed by ‘Mood swing’ with adjusted p=0.012; ‘Obsessional elements’ with adjusted p=0.034; ‘Thought disorders’ with adjusted p=0.000 and ‘Educational underachievement’ with adjusted p=0.017. For example, in the absence of ‘Bizarre behaviours’, presence of ‘Sad mood’ and absence of ‘Thought disorders’, a node (group or profile) of 50 was identified out of 82 initial bipolar disorder diagnoses (61%) and 14 out of 123 initial schizophrenia diagnoses (11%).

Discussion

Comparison of both populations and the decision tree

We succeeded in extracting a decision tree offering good predictability in our population as 77.6% of the patients received the correct diagnosis.

All variables, apart from one, were found to be evenly distributed across both diagnostic categories. This finding may seem disappointing but it highlights the specific difficulties encountered. We harnessed symptoms characterising childhood and adolescence, and drew distinct trajectories between patients developing SZ and MSD. However, the time distribution was not specific or pathognomonic of one diagnosis. Hence the early identification and differentiation of high-risk profiles is complex.

Our study does not feature the conventionally high rate of comorbid ADHD diagnoses. Up to 58% of children with ADHD are later diagnosed with schizophrenia [23] and between 50 and 80% of those are further diagnosed with bipolar disorder [24]. Only 2.4% of the diagnoses in each group accounted for ADHD. The difference might be explained by the retrospective research involving medical records at a time when such diagnoses were not commonplace in France. Moreover, many consultations took place during adolescence, a time when undiagnosed ADHD may have been classified as behavioural disorders and educational difficulties. With reference to the MSD population in particular, it should be noted that the subjects were mostly female, and the diagnosis of ADHD is less accessible and generally delayed for women given the lack of hyperactivity.

Surprisingly, behavioural/impulse control-related symptoms (p<0.05) were linked only to the SZ diagnosis. More predictably, mood-related symptoms were associated with the MSD diagnosis. Since oppositional behaviours and mood-related symptoms are known to typically appear during adolescence in the general population [25], it is crucial to pay specific attention to their evolution and interaction with other symptoms. This approach could reveal a high-risk profile tending towards SZ or MSD. A significant correlation was noted between functional symptoms and MSD diagnosis, with the exception of encopresis, which was linked to SZ. It has also been suggested that enuresis could be indicative of predisposition towards schizophrenia [26]. Among anxiety-related symptoms, anxiety/separation anxiety was linked to MSD but phobic and obsessional elements were associated with SZ. It is important to note the impact of growing up with a mentally ill parent on the development of psychiatric disorders such as anxiety, as evidenced in several studies [27, 28]. Sixteen salient positive and negative symptoms were observed. They were linked solely to the diagnosis of SZ with significant changes in terms of behaviour or function.

These results also echo the findings of a study comparing axis I antecedents before the age of 18, namely unipolar depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia [29]. Compared to unipolar depression, schizophrenia was significantly associated with ADHD, a disorder connected with cognitive and behavioural symptoms in our study, and primary nocturnal enuresis. There were also significant links between schizophrenia and social phobia and the ADHD inattentive subtype compared to bipolar disorder.

The decision tree failed to give the appropriate predictive diagnosis in 46 cases out of 205. It is obvious that most of the medical records in question contained very few significant data given the succinct observations or brief follow-up. Moreover, the symptoms were frequently identified more than five years (sometimes ten) before a diagnosis was made. We can assume that they were probably associated primarily with the pre-morbid as opposed to the prodromal phase, which is recognised as being less specific. However, eight SZ cases did not meet these criteria as they exhibited symptoms relating to virtually all dimensions over time. These included mood-related symptoms, which were strongly correlated with MSD diagnosis, and a few positive symptoms. Among the SZ cases given the incorrect predictive diagnosis, five patients presented with learning disabilities and five others exhibited significant behavioural changes. This highlights the importance of gathering such data, although they did not appear as a node in the decision tree.

Among the MSD cases given the wrong predictive diagnosis, we noted several positive symptoms linked to other symptoms. These affected a number of dimensions. Eight cases demonstrated the co-existence of mood-related symptoms [1,2,3,4,5, to 6] during adolescence. 0 to 3 were more or less negative and inclining spontaneously towards the diagnosis of MSD, albeit with consequently positive symptoms [3,4,5,6,7, to 8]. Those symptoms are probably more evident and could potentially dominate the clinical picture. A profile therefore emerges combining mood-related symptoms consistent with evolution towards MSD and patent psychotic symptoms presented by less than one-third of the patients in our MSD group.

This atypical profile, at the crossroads of the distinct evolutive trajectories previously described, may be explained by the fact that mania and schizophrenia prodrome characteristics overlapped considerably [21]. Although a clinically high-risk population could be defined, the overlap with the schizophrenia prodrome warrants further investigation and comparison of both illness prodromes. Three subgroups based on pre-morbid adjustment (PMA) were recently identified [30]. PMA measurements include performance during childhood and adolescence in prominent developmental domains such as social and academic functioning [31], using criteria similar to some of the symptoms in our grid. The proportion of SZ and MSD diagnoses, current neurocognition and functioning did not differ between the three identified clusters. These findings are consistent with the common neurodevelopmental hypothesis regarding SZ and MSD, with subgroups exhibiting distinct PMA trajectories that cut across various disorders.

The decision tree could be supplemented and combined with other techniques ranging from a semi-structured interview to genetics [32] via biomarkers [33]. In research, models combining different types of data offer considerable perspectives in personalised medicine [34, 35]. In daily practice, our study could provide targeted diagnostic assistance in documenting medical histories. It could provide clinicians with a global overview of adolescent symptoms combined with the presence of psychosocial factors or a psychiatric family history. This knowledge combined with an awareness of atypical profiles should promote early identification of high-risk SZ or MSD patients, which would facilitate early prevention and effective intervention [11, 36].

General description and trajectories through childhood and adolescence

Whereas the schizophrenia gender ratio is generally one to one, our SZ population had a 67.5% male component. This can be explained by the time-frame analysed, which did not explore symptoms between the age of 18 and the age of diagnosis. Indeed, the first psychotic episode is usually identified between the age of 15 and 25 in males, and later in females [37]. Moreover, the prodromal phase tends to last 5 years on average [38]. On the contrary, our MSD population mostly comprised female subjects (71.6%) with bipolar disorders affecting men and women to equal extent [39]. Based on a 2021 study involving minors, girls were shown to have better mental health skills than boys of the same age. These skills include emotional regulation, social relationships and empathy, etc. Given their introspection, girls are more capable of asking for and accepting help [40]. We can assume that young girls seek more help during adolescence – hence their over-representation in the study sample.

According to the HAS, the French public health authority, the most interesting age-group for screening is the 15 to 25 year-old age group, which exceeds our timeframe. This information is consistent with the average age of diagnosis in our study: 20.6 (SD=3.9) for the SZ group, 20.9 (SD=4.1) for the MSD group.

The initial psychiatric consultation mostly took place at the end of childhood (at 12.1 years of age on average SD=4.8 for SZ, 11.7 years of age SD=4.5 for MSD), which coincides with the pre-morbid phase. It groups together relatively non-specific symptoms common to the psychotic pre-morbid phase, namely cognitive, anxiety-related symptoms and oppositional behaviours as identified in a meta-analysis [1]. A significant change in behaviour or function was noted in 23.1% of the MSD group at an average age of 14.2 years (SD=2.1). This concept is even more prevalent in the SZ group, affecting 52% of patients with an average age of 14.9 years (SD=1.8). It may correspond to the noisy entry into the prodromal phase alongside puberty.

During the data analysis, a wide range of symptoms appeared in a specific order (Figures 1 and 2). Other studies have also shown that the prodromal phase does not comprise pathognomonic symptoms but a succession of symptoms over time [38, 41]. SZ patients tended to present more difficulties at each developmental stage (neurocognitive deficits, poorer academic and social skills) and ongoing difficulties potentially exacerbated with the emergence of behavioural, negative and positive symptoms. Moreover, bizarre behaviours and the earlier entry point in the decision tree are indicative of positive symptoms (14.7 years old, SD=2.9). Future schizophrenic patients were already described as strange, bizarre children [38, 42]. Patients developing a bipolar disorder were more likely to exhibit anxiety-related symptoms in childhood and mood-related symptoms during adolescence, as shown in the literature [1]. The prevalence of suicidal thoughts is marked in both groups (37.4% at an average age of 15.2 years for SZ and 39% at an average age of 14.8 years for MSD), echoing the continued importance of suicidal risk prevention during the recovery period [43].

Our observations are consistent with a 2017 literature review [16] highlighting the fact that subjects later diagnosed with schizophrenia and, to a lesser extent, those subsequently diagnosed with bipolar disorder, showed signs of pre-morbid abnormalities such as developmental deviations and adjustment problems. Nonetheless, the predictive risk of each isolated developmental marker remains low. We are facing the same issue: the absence of pathognomonic symptoms tending towards schizophrenia or mood spectrum disorder. Thus, some patients experienced their first pre-morbid symptoms during adolescence. During the latter, subjects may display a labile mood because of puberty, but clinicians should pay close attention to these symptoms as they may be indicative of schizophrenia or mood spectrum disorder”.

Study strengths and limitations

One of our main limitations lies in the retrospective examination of the medical records. Some were based on several consultations with few relevant clinical features and/or a limited window of time, while others were much more evidence-based. This may lead to false negatives in the results presented. Furthermore, it is a well-known fact that decision trees are unstable, i.e. a minor change in the data can lead to a significant change in the structure of the optimal decision tree. In terms of our sample, it is limited by the number of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder in the region and the small proportion of subjects with a paediatric psychiatric record. Moreover, we included subjects with F33 and F34 diagnoses who may have another clinical profile. This could explain why there are more incorrect diagnoses in the decision tree for subjects with a mood spectrum disorder (39%). Increasing the size of the cohort and comparing it to a control group could generate greater specificity for the pre-morbid and prodromal phases of each condition. Finally, like all retrospective studies, this particular study is biased. The quality of the data obtained using this method does not equate to that of a prospective study. Finally, only patients with childhood and adolescent psychiatric consultations were enrolled in the study. This study still provides an overview of the distinct trajectories between both populations and the construction of a decision tree. This tool offers several advantages in that it is easy to understand and interpret following a brief explanation. Moreover, it can be combined with other decision techniques.

Conclusion

The results of this study, which compares the evolution and age of onset of various symptom categories during childhood and adolescence, allowed us to plot separate trajectories for patients developing schizophrenia or mood spectrum disorder. Overall, our results corroborated current literature findings and are consistent with the neurodevelopmental process which exhibits pre-morbid and prodromal phases. Patients with schizophrenia during adulthood tended to present more difficulties at each developmental stage such as neurocognitive deficits and poorer academic and social skills. These difficulties persist and, in some instances, are exacerbated with the emergence of negative and positive behavioural symptoms. Patients with mood spectrum disorder during adulthood are more likely to have exhibited anxiety-related symptoms in childhood and mood-related symptoms during adolescence. The frequency of suicidal thoughts was substantial in both groups, which emphasises the importance of suicidal risk prevention during the recovery period [43]. Nevertheless, the symptoms were found to be non-pathognomonic during the clinical course of both disorders. We succeeded in extracting a decision tree based on variables associated with one diagnosis. It offered good predictability in our population: 77.6% of patients received a well-indexed diagnosis. We noticed an atypical profile in future bipolar patients as some exhibited numerous positive symptoms combined with more conventional mood-related symptoms. The combination of all these data could be instrumental in the early identification of high-risk patients, thereby facilitating early prevention and intervention [25]. Indeed, certain intervention strategies may be proposed in the early stages of disorder progression. For example, in the case of schizophrenia, subjects at high risk of clinical psychosis [44] can benefit from programmes based on remediation, namely “the Recognition and Prevention (RAP) programme” [45]. Other early interventions are available based on cognitive-behavioural therapy such as cognitive insight improvement, stress management and family focus, etc. and for the treatment of comorbidities (anxiety and depression), as recommended by the European Psychiatry Association [46,47,48]. These treatment options are increasingly available in routine clinical practice through specific centres [10, 11].

Fewer studies are available for subjects with mood spectrum disorders. However, it is still crucial to make the correct diagnosis in the early stages and offer specific care in the form of psychological education, stress management and addiction prevention, as recommended for a number of serious mental illnesses [49].

Moreover, transdiagnostic studies tend to emerge in the scientific literature, sometimes challenging conventional Kraepelinian dichotomy [50], sometimes assuming a continuum between bipolar disorders and schizophrenia. A number of domains are affected, such as genetics and neurotransmitters [32, 51, 52], neuro-imagery [53, 54] with a retinal focus [55, 56], immunology and microbiome [57], cognitive evaluation and pre-morbid adjustment [30, 58]. Some authors advocate a less categorial, more dimensional study of psychiatric illness, proposing models such as the RDoC (Research Domain Criteria) [59] or, more specifically, ESSENCE (Early Symptomatic Syndromes Eliciting Neurodevelopmental Clinical Examinations), which suggest the co-existence of disorders and pooling of symptoms across disorders as the rule rather than the exception [60]. The global expectation is that the identification of neurophysiology-based syndromes will eventually lead to improved outcomes.

Availability of data and materials

Material (data grid used for the data collection) and data are available by contacting the correspondence author.

Abbreviations

- MSD:

-

Mood Spectrum Disorder

- SZ:

-

Schizophrenia

References

Geoffroy PA, Leboyer M, Scott J. Predicting bipolar disorder: What can we learn from prospective cohort studies? Encephale. 2015 Feb;41(1):10–6.

American Psychiatric Association. DIAGNOSTIC AND STATISTICAL MENTAL DISORDERS MANUAL OF FIFTH EDITION DSM-5. Vol. 17, American Psychiatric Publishing. 2013. 461–462 p.

Jääskeläinen E, Juola P, Hirvonen N, McGrath JJ, Saha S, Isohanni M, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of recovery in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull [Internet]. 2013 Nov [cited 2021 Aug 25];39(6):1296–306. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23172003/

Malhi GS, Bargh DM, Coulston CM, Das P, Berk M. Predicting bipolar disorder on the basis of phenomenology: Implications for prevention and early intervention. Vol. 16, Bipolar Disorders. 2014. p. 455–70.

Hauser M, Correll CU. The significance of at-risk or prodromal symptoms for bipolar i disorder in children and adolescents [Internet]. Vol. 58, Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Can J Psychiatry; 2013 [cited 2021 Aug 25]. p. 22–31. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23327753/

HAS. Patient avec un trouble bipolaire: repérage et prise en charge initiale en premier recours. [Internet]. [cited 2020 Mar 19]. Available from: 7. Medeiros GC, Senço SB, Lafer B, Almeida KM. Association between duration of untreated bipolar disorder and clinical outcome: Data from a Brazilian sample. Rev Bras Psiquiatr [Internet]. 2016 Jan 1 [cited 2021 Aug 25];38(1):6–10. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26785105/

Rios AC, Noto MN, Rizzo LB, Mansur R, Martins FE, Grassi-Oliveira R, et al. Early stages of bipolar disorder: Characterization and strategies for early intervention. Rev Bras Psiquiatr [Internet]. 2015 Oct 1 [cited 2021 Aug 25];37(4):343–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26692432/

McGlashan TH. Duration of untreated psychosis in first-episode schizophrenia: Marker or determinant of course? [Internet]. Vol. 46, Biological Psychiatry. Biol Psychiatry; 1999 [cited 2021 Aug 25]. p. 899–907. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10509173/

Schimmelmann BG, Huber CG, Lambert M, Cotton S, McGorry PD, Conus P. Impact of duration of untreated psychosis on pre-treatment, baseline, and outcome characteristics in an epidemiological first-episode psychosis cohort. J Psychiatr Res [Internet]. 2008 Oct [cited 2021 Aug 25];42(12):982–90. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18199456/

Marshall M, Rathbone J. Early intervention for psychosis. Schizophr Bull [Internet]. 2011 Nov [cited 2021 Aug 25];37(6):1111–4. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21908851/

Schultze-Lutter F, Michel C, Schmidt SJ, Schimmelmann BG, Maric NP, Salokangas RKR, et al. EPA guidance on the early detection of clinical high risk states of psychoses. Eur Psychiatry [Internet]. 2015 Mar 1 [cited 2021 Aug 25];30(3):405–16. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25735810/

Lichtenstein P, Yip BH, Björk C, Pawitan Y, Cannon TD, Sullivan PF, et al. Common genetic determinants of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in Swedish families: a population-based study. Lancet [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2021 Aug 25];373(9659):234–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19150704/

Serological Documentation of Maternal Influenza Exposure and Bipolar Disorder in Adult Offspring. Am J Psychiatry [Internet]. 2014 May [cited 2021 Aug 20];171(5):557–63. Available from: http://psychiatryonline.org/doi/abs/10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13070943

Jiménez-López E, Aparicio AI, Sánchez-Morla EM, Rodriguez-Jimenez R, Vieta E, Santos JL. Neurocognition in patients with psychotic and non-psychotic bipolar I disorder. A comparative study with individuals with schizophrenia. J Affect Disord [Internet]. 2017 Nov 1 [cited 2021 Aug 25];222:169–76. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28709024/

How Genes and Environmental Factors Determine the Different Neurodevelopmental Trajectories of Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder. Schizophr Bull [Internet]. 2012 Mar [cited 2021 Aug 20];38(2):209–14. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/schizophreniabulletin/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/schbul/sbr100

Parellada M, Gomez-Vallejo S, Burdeus M, Arango C. Developmental Differences between Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder. Schizophr Bull [Internet]. 2017 Nov 1 [cited 2021 Aug 25];43(6):1176–89. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29045744/

Fava GA, Kellner R. Staging: a neglected dimension in psychiatric classification [Internet]. Vol. 87, Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. Acta Psychiatr Scand; 1993 [cited 2021 Aug 25]. p. 225–30. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8488741/

Yung AR, Nelson B, Stanford C, Simmons MB, Cosgrave EM, Killackey E, et al. Validation of “prodromal” criteria to detect individuals at ultra high risk of psychosis: 2 year follow-up. Schizophr Res [Internet]. 2008 Oct [cited 2021 Aug 25];105(1–3):10–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18765167/

Krebs MO, Magaud E, Willard D, Elkhazen C, Chauchot F, Gut A, et al. Évaluation des états mentaux à risque de transition psychotique: Validation de la version française de la CAARMS. Encephale [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2021 Aug 25];40(6):447–56. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25127895/

Howes OD, Lim S, Theologos G, Yung AR, Goodwin GM, McGuire P. A comprehensive review and model of putative prodromal features of bipolar affective disorder [Internet]. Vol. 41, Psychological Medicine. Psychol Med; 2011 [cited 2021 Aug 25]. p. 1567–77. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20836910/

Correll CU, Penzner JB, Frederickson AM, Richter JJ, Auther AM, Smith CW, et al. Differentiation in the preonset phases of schizophrenia and mood disorders: Evidence in support of a bipolar mania prodrome. Schizophr Bull [Internet]. 2007 Sep [cited 2021 Aug 25];33(3):703–14. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17478437/

Obacz C, Jay N, Ligier F, Kabuth B. Childhood of an adult schizophrenia sample. A retrospective study of 50 patients. Neuropsychiatr Enfance Adolesc. 2012;60(7–8).

Niemi LT, Suvisaari JM, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Lönnqvist JK. Childhood developmental abnormalities in schizophrenia: Evidence from high-risk studies [Internet]. Vol. 60, Schizophrenia Research. Schizophr Res; 2003 [cited 2021 Aug 25]. p. 239–58. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12591587/

Elmaadawi AZ. Risk for emerging bipolar disorder, variants, and symptoms in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, now grown up. World J Psychiatry [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2021 Aug 25];5(4):412. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26740933/

Trouble des conduites chez les enfants et les adolescents [Internet]. 2005. Available from: http://www.ipubli.inserm.fr/handle/10608/140.

Hyde TM, Deep-Soboslay A, Iglesias B, Callicott JH, Gold JM, Meyer-Lindenberg A, et al. Enuresis as a premorbid developmental marker of schizophrenia. Brain [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2021 Aug 25];131(9):2489–98. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18669483/

DeVylder JE, Lukens EP. Family history of schizophrenia as a risk factor for axis I psychiatric conditions. J Psychiatr Res [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2021 Aug 25];47(2):181–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23102629/

Özdemir O, Coşkun S, Aktan Mutlu E, Özdemir PG, Atli A, Yilmaz E, et al. Bipolar Bozukluğu Olan Hastalarda Aile Öyküsü. Noropsikiyatri Ars [Internet]. 2016 Sep 1 [cited 2021 Aug 25];53(3):276–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28373808/

Rubino IA, Frank E, Croce Nanni R, Pozzi D, Lanza Di Scalea T, Siracusano A. A comparative study of axis I antecedents before age 18 of unipolar depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Psychopathology [Internet]. 2009 Aug [cited 2021 Aug 25];42(5):325–32. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19672135/

Chan CC, Shanahan M, Ospina LH, Larsen EM, Burdick KE. Premorbid adjustment trajectories in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: A transdiagnostic cluster analysis. Psychiatry Res [Internet]. 2019 Feb 1 [cited 2021 Aug 25];272:655–62. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30616137/

Cannon-Spoor HE, Potkin SG, Jed Wyatt R. Measurement of premorbid adjustment in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull [Internet]. 1982 [cited 2021 Aug 25];8(3):470–80. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7134891/

Ruderfer DM, Fanous AH, Ripke S, McQuillin A, Amdur RL, Gejman P V., et al. Polygenic dissection of diagnosis and clinical dimensions of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry [Internet]. 2014 Sep 11 [cited 2021 Aug 25];19(9):1017–24. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24280982/

Fryar-Williams S, Strobel JE. Biomarker case-detection and prediction with potential for functional psychosis screening: Development and validation of a model related to biochemistry, sensory neural timing and end organ performance. Front Psychiatry [Internet]. 2016 Apr 14 [cited 2021 Aug 25];7(APR). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27148083/

Birur B, Kraguljac NV, Shelton RC, Lahti AC. Brain structure, function, and neurochemistry in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder- A systematic review of the magnetic resonance neuroimaging literature [Internet]. Vol. 3, npj Schizophrenia. NPJ Schizophr; 2017 [cited 2021 Aug 25]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28560261/

Schmitt A, Rujescu D, Gawlik M, Hasan A, Hashimoto K, Iceta S, et al. Consensus paper of the WFSBP Task Force on Biological Markers: Criteria for biomarkers and endophenotypes of schizophrenia part II: Cognition, neuroimaging and genetics [Internet]. Vol. 17, World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. World J Biol Psychiatry; 2016 [cited 2021 Aug 25]. p. 406–28. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27311987/

Sanchez-Moreno J, Martinez-Aran A, Vieta E. Treatment of Functional Impairment in Patients with Bipolar Disorder [Internet]. Vol. 19, Current Psychiatry Reports. Curr Psychiatry Rep; 2017 [cited 2021 Aug 25]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28097635/

Épidémiologie des troubles schizophréniques [Internet]. [cited 2021 Aug 20]. Available from: https://www.em-consulte.com/article/102970/epidemiologie-des-troubles-schizophreniques

Häfner H, Maurer K, An Der Heiden W. ABC Schizophrenia study: An overview of results since 1996 [Internet]. Vol. 48, Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol; 2013 [cited 2021 Aug 25]. p. 1021–31. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23644725/

Patient avec un trouble bipolaire : repérage et prise en charge initiale en premier recours [Internet]. 2015. Available from: https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/c_1747465/fr/patient-avec-un-trouble-bipolaire-reperage-et-prise-en-charge-initiale-en-premier-recours.

O'Connor M, Arnup SJ, Mensah F, Olsson C, Goldfeld S, Viner RM, Hope S. Natural history of mental health competence from childhood to adolescence. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2021 Aug 16:jech-2021-216761. doi: 10.1136/jech-2021-216761. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34400516.42.

Duffy A. Toward a comprehensive clinical staging model for bipolar disorder: Integrating the evidence [Internet]. Vol. 59, Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Can J Psychiatry; 2014 [cited 2021 Aug 25]. p. 659–66. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25702367/

Olin SCS, Mednick SA. Risk factors of psychosis: Identifying vulnerable populations premorbidly [Internet]. Vol. 22, Schizophrenia Bulletin. Schizophr Bull; 1996 [cited 2021 Aug 25]. p. 223–40. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8782283/

Foster T. Schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: No recovery without suicide prevention [Internet]. Vol. 207, British Journal of Psychiatry. Br J Psychiatry; 2015 [cited 2021 Aug 25]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26527661/

Laprevote V, Heitz U, Di Patrizio P, Studerus E, Ligier F, Schwitzer T, Schwan R, Riecher-Rössler A. Pourquoi et comment soigner plus précocement les troubles psychotiques ? [Why and how to treat psychosis earlier?]. Presse Med. 2016 Nov;45(11):992-1000. French. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lpm.2016.07.011. Epub 2016 Aug 21. PMID: 27554461.

Cornblatt BA, Carrión RE, Auther A, McLaughlin D, Olsen RH, John M, Correll CU. Psychosis Prevention: A Modified Clinical High Risk Perspective From the Recognition and Prevention (RAP) Program. Am J Psychiatry. 2015 Oct;172(10):986-94. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.13121686. Epub 2015 Jun 5. PMID: 26046336; PMCID: PMC4993209.

Michel C, Toffel E, Schmidt SJ, Eliez S, Armando M, Solida-Tozzi A, Schultze-Lutter F, Debbané M. Détection et traitement précoce des sujets à haut risque clinique de psychose : définitions et recommandations [Detection and early treatment of subjects at high risk of clinical psychosis: Definitions and recommendations]. Encephale. 2017 May;43(3):292-297. French. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.encep.2017.01.005. Epub 2017 Mar 25. PMID: 28347521

Schlosser DA, Miklowitz DJ, O'Brien MP, De Silva SD, Zinberg JL, Cannon TD. A randomized trial of family focused treatment for adolescents and young adults at risk for psychosis: study rationale, design and methods. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2012 Aug;6(3):283-91. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2011.00317.x. Epub 2011 Dec 20. PMID: 22182667; PMCID: PMC4106700.

Catalan A, Salazar de Pablo G, Vaquerizo Serrano J, Mosillo P, Baldwin H, Fernández-Rivas A, Moreno C, Arango C, Correll CU, Bonoldi I, Fusar-Poli P. Annual Research Review: Prevention of psychosis in adolescents - systematic review and meta-analysis of advances in detection, prognosis and intervention. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2021 May;62(5):657-673. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13322. Epub 2020 Sep 14. PMID: 32924144.50.

Leopold K, Bauer M, Bechdolf A, Correll CU, Holtmann M, Juckel G, et al. Bipolar Disord. 2020 Aug;22(5):517–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/bdi.12894.

Rybakowski JK. 120th Anniversary of the Kraepelinian Dichotomy of Psychiatric Disorders [Internet]. Vol. 21, Current Psychiatry Reports. Curr Psychiatry Rep; 2019 [cited 2021 Aug 25]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31264045/

Witt SH, Streit F, Jungkunz M, Frank J, Awasthi S, Reinbold CS, et al. Genome-wide association study of borderline personality disorder reveals genetic overlap with bipolar disorder, major depression and schizophrenia. Transl Psychiatry [Internet]. 2017 Jun 20 [cited 2021 Aug 25];7(6):e1155. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28632202/

van Hulzen KJE, Scholz CJ, Franke B, Ripke S, Klein M, McQuillin A, et al. Genetic Overlap Between Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Bipolar Disorder: Evidence From Genome-wide Association Study Meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry [Internet]. 2017 Nov 1 [cited 2021 Aug 25];82(9):634–41. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27890468/

Karcher NR, Rogers BP, Woodward ND. Functional Connectivity of the Striatum in Schizophrenia and Psychotic Bipolar Disorder. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging [Internet]. 2019 Nov 1 [cited 2021 Aug 25];4(11):956–65. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31399394/

Mellem MS, Liu Y, Gonzalez H, Kollada M, Martin WJ, Ahammad P. Machine Learning Models Identify Multimodal Measurements Highly Predictive of Transdiagnostic Symptom Severity for Mood, Anhedonia, and Anxiety. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging [Internet]. 2020 Jan 1 [cited 2021 Aug 25];5(1):56–67. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31543457/

Lavoie J, Maziade M, Hébert M. The brain through the retina: The flash electroretinogram as a tool to investigate psychiatric disorders [Internet]. Vol. 48, Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry; 2014 [cited 2021 Aug 25]. p. 129–34. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24121062/

Hébert M, Mérette C, Gagné AM, Paccalet T, Moreau I, Lavoie J, et al. The Electroretinogram May Differentiate Schizophrenia From Bipolar Disorder. Biol Psychiatry [Internet]. 2020 Feb 1 [cited 2021 Aug 25];87(3):263–70. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31443935/

Dickerson F, Severance E, Yolken R. The microbiome, immunity, and schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;62:46–52.

Demily C, Jacquet P, Marie-Cardine M. How to differentiate schizophrenia from bipolar disorder using cognitive assessment? Encephale [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2021 Aug 25];35(2):139–45. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19393382/

Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, Heinssen R, Pine DS, Quinn K, et al. Research Domain Criteria (RDoC): Toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2010 Jul;167(7):748–51.

Gillberg C. The ESSENCE in child psychiatry: Early Symptomatic Syndromes Eliciting Neurodevelopmental Clinical Examinations. Res Dev Disabil [Internet]. 2010 Nov [cited 2021 Aug 25];31(6):1543–51. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20634041/

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors are responsible for the research reported and agree to be cited as co-authors. They have accepted authorship. ML, BK and FL were involved in the concept and design, EA participated in data analysis and interpretation, and all were involved in drafting or revising the manuscript. They have all approved the manuscript as submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The experimental EDIPHAS protocol was approved by two French IRB, responsible for regulating medical research:

the Comité Consultatif sur le Traitement de l’Information en matière de Recherche en Santé, the CCTIRS, an advisory committee for information processing in Health Research which includes Ethical considerations, and

the Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés, the CNIL, a French national Data processing agency, under authorisation number DR-2013-042.

These authorisations were extended twice to include additional hospital facilities and to approve the changes made to the data collection form. All methods were applied in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

In this French study, a consent to participate was not required, as approved by the CCTIRS. However, the subjects of the study were contacted by a letter either send to their place of residence or else through their referring psychiatrist at the time. This letter contained clear, appropriate and fair information on the objectives of the study and their right to refuse access and review of their old file, while emphasizing that such a choice would have no impact whatsoever on their treatment. Two eligible subjects refused to participate.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing or potential conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Léger, M., Wolff, V., Kabuth, B. et al. The mood disorder spectrum vs. schizophrenia decision tree: EDIPHAS research into the childhood and adolescence of 205 patients. BMC Psychiatry 22, 194 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-03835-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-03835-0