Abstract

Objective

Most weight loss research focuses on weight as the primary outcome, often to the exclusion of other physiological or psychological measures. This study aims to provide a holistic evaluation of the effects from weight loss interventions for individuals with obesity by examining the physiological, psychological and eating disorders outcomes from these interventions.

Methods

Databases Medline, PsycInfo and Cochrane Library (2011–2016) were searched for randomised controlled trials and systematic reviews of obesity treatments (dietary, exercise, behavioural, psychological, pharmacological or surgical). Data extracted included study features, risk of bias, study outcomes, and an assessment of treatment impacts on physical, psychological or eating disorder outcomes.

Results

From 3628 novel records, 134 studies met all inclusion criteria and were evaluated in this review. Lifestyle interventions had the strongest evidence base as a first-line approach, with escalation to pharmacotherapy and bariatric surgery in more severe or complicated cases. Quality of life was the most common psychological outcome measure, and improved in all cases where it was assessed, across all intervention types. Behavioural, psychological and lifestyle interventions for weight loss led to improvements in cognitive restraint, control over eating and binge eating, while bariatric surgery led to improvements in eating behaviour and body image that were not sustained over the long-term.

Discussion

Numerous treatment strategies have been trialled to assist people to lose weight and many of these are effective over the short-term. Quality of life, and to a lesser degree depression, anxiety and psychosocial function, often improve alongside weight loss. Weight loss is also associated with improvements in eating disorder psychopathology and related measures, although overall, eating disorder outcomes are rarely assessed. Further research and between-sector collaboration is required to address the significant overlap in risk factors, diagnoses and treatment outcomes between obesity and eating disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Plain English Summary

Obesity and eating disorders are often viewed as distinct problems on opposite ends of the weight spectrum, but in actuality, they share a number of risk and protective factors and frequently co-occur. Individuals with binge eating disorder are often overweight, and individuals that are overweight are at an increased risk of developing eating disorders. Despite this, weight loss interventions usually focus on physical factors, such as changes in weight or body composition, to the exclusion of other factors, such as psychological well-being or eating disorders.

In this review, we conduct a detailed examination of published literature on the range of available interventions for overweight and obesity, taking physical, psychological and eating disorders outcomes into equal consideration. ‘Lifestyle’ interventions that include exercise, dietary and behavioural components have the strongest evidence as a first-line approach, while obesity (bariatric) surgery is the most effective intervention in terms of the amount of weight lost. Quality of life is not commonly measured, but where reported it tends to improve alongside weight loss. Interventions that included behavioural or psychological components had the most positive impacts on eating disorders psychopathology and related measures, although these outcomes were only reported in a small number of studies.

Background

Obesity and eating disorders are significant public health concerns that are associated with a range of adverse physical and psychological outcomes. In Australia, more than 60% of adults and 25% of children and adolescents are overweight or obese [1, 2], with an additional 16% presenting with disordered eating behaviours or eating disorders [3]. The rate of both eating disorders [4] and obesity [2] is increasing in the Australian population, and recent evidence indicates that the rate of comorbid obesity and eating disorder behaviours has increased more rapidly than either disorder alone [5]. Individuals with comorbid obesity and eating disorders face the added difficulty of receiving care for both the medical complications associated with obesity and the psychosocial impairments associated with eating disorders [5].

The reasons for such a large increase in comorbid obesity and eating disorders in a relatively short period of time are unclear, but media and weight-reduction campaigns have been suggested as precipitating factors [5]. Media exposure may increase sociocultural pressures to attain an ideal body image and contribute to body dissatisfaction [6,7,8], and community-based weight-reduction campaigns may inadvertently stigmatise the individuals they intend to help [9, 10] by encouraging dieting and physical exercise as a means to attain an ideal body weight or shape [11,12,13].

A growing body of evidence highlights the significant shared space between disorders at both ends of the weight spectrum. Obesity and eating disorders share a number of risk factors that apply to a broad range of eating- and weight-related problems [14,15,16]. These include (i) individual factors such as dieting, unhealthy weight-control behaviours, weight and shape concerns, and self-esteem issues; (ii) social factors, such as parental and peer weight and shape related behaviours, including bullying and histories of abuse; and (iii) societal factors, such as sociocultural norms, media exposure and weight discrimination. Collectively, these factors place enormous pressure on individuals to conform to an ideal weight and shape, and contribute to body dissatisfaction that is a predictor of both eating disorders and excessive weight gain [17].

Overweight individuals are at increased risk of disordered eating and eating disorders compared with the general population [18]. At the same time, individuals with binge eating disorder (BED) and individuals who use unhealthy weight-control practices (e.g. fasting, purging and diet pills), such as those with bulimia nervosa (BN), are at increased risk of overweight and obesity [19,20,21,22]. Further, individuals with comorbid BED and obesity are at increased risk of weight gain and related complications [23], and experience a higher rate of medical problems [24] and depression [25] than obese individuals without BED. Individuals with eating disorders are more than twice as likely to contact health professionals or weight loss centres for weight reduction assistance [4] than they are to seek treatment specifically for their eating disorder [4]. This raises the concern that interventions targeting weight loss may exacerbate or contribute to the development of disordered eating or eating disorders [26] by encouraging behaviours that increase focus on body shape and weight [27].

Since the vast majority of weight loss intervention research focuses on weight as the primary outcome, often to the exclusion of other physiological or psychological measures, the potential impact of weight loss interventions on eating disorders and overall wellbeing is unclear. Therefore, this systematic review aims to provide a holistic evaluation of the effects from weight loss interventions for individuals with obesity, assessing physiological, psychological and eating disorders outcomes. Due to the large volume of literature on the topic, we constrained our search to cases of uncomplicated obesity – that is, individuals who were otherwise healthy, and with the exception of BED, had no physical or psychological comorbidities. A synthesis of outcomes is then used to identify gaps in the literature and guide our recommendations for future research and practice that encourages an integrated approach to the prevention and management of obesity and eating disorders.

Methods

This review was conducted in accordance to the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews [28]. Searches of the electronic databases Medline, PsycInfo and Cochrane Library were conducted in February 2016 using both medical subject headings (MeSH) and equivalent free text searches for terms pertaining to obesity (overweight, overnutrition, hyperphagia), obesity interventions (exercise, diet, psychological, pharmacological, behavioural and surgical), and eating disorders (anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, other specified feeding and eating disorders).

Study selection

We considered peer-reviewed systematic reviews (SRs) and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published in 2011 or more recent, or in the case of SRs, an original or updated search date of 2011 or more recent. These criteria were chosen because of the large volume of available literature, because older RCTs will be evaluated within recent systematic reviews, and because recent systematic reviews eclipse non-recent systematic reviews. We excluded non-English studies, studies reporting primarily qualitative or methodological data, studies focused on preventative interventions and studies in which the outcomes of an overweight or obesity intervention were not the main focus of the study.

The target sample included overweight or obese males and females ranging in age from 12–65 years. Adolescents (12–18 years) were assessed separately from adults (18–65 years). Because of prominent differences in treatment strategies, paediatric and elderly patients were excluded from consideration. The primary interventions evaluated in this review were dietary, exercise/physical activity, psychological/behavioural, pharmacological and surgical interventions, while the primary outcome measures were standardized anthropometric measures (e.g., body mass index (BMI) and body weight), standardized body composition measures (e.g., body fat mass), psychological, eating disorder and quality of life measures, and reports of adverse treatment effects.

Assessment of studies

All included studies were assessed first individually and second collectively (by TP and SB, see acknowledgements) according to treatment intervention. Study assessment included appraisal of study quality, clinical impact and consistency. Each assessment item was scored as high, moderate or low by one of two reviewers, and a subset of studies (10%) was scored by both reviewers to assess accuracy. Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

The Overview Quality Assessment Questionnaire (OQAQ) [29] and the Jadad Scale [30] were used to assess study quality and risk of bias for SRs and RCTs, respectively [see Additional file 1]. The OQAQ includes items that address the suitability of the search methods, study selection, data assessment and pooling, while the Jadad scale includes items that address the suitability of randomisation, blinding, and procedures to account for withdrawals and dropouts. The clinical impact rating was derived by assessing the statistical precision, effect size, and relevance to patients compared with other treatments or no treatment, based on the outcomes reported by the study author (i.e., rather than based on meta-analyses). Finally, consistency was assessed for SRs based on the consistency of included RCTs (adapted from NHMRC guidelines [31]) and the statistical heterogeneity of included studies (when this data were available).

Following the assessment of each individual SR and RCT, the evidence was evaluated for each intervention, taking into account the number, quality, clinical impact and consistency of included studies. Each factor was assigned a rating of poor, satisfactory, good or excellent based on the degree to which relevant criteria (adapted from the NHMRC Body of Evidence Matrix [31]) [see Additional file 1] were fulfilled. Table 1 presents a summary of all interventions evaluated in this review, along with a summative assessment of the breadth of the evidence base (quality/quantity of studies), consistency and clinical impact of included studies.

Results

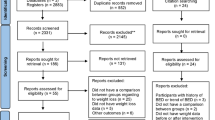

The search strategy yielded a total of 3628 citations after removal of duplicates. Following exclusion of studies that did not meet inclusion criteria, 134 studies remained, of which 33 were SRs and 101 were RCTs (Fig. 1). Additional files summarize the study features, risk of bias, study outcomes, clinical impact and citation information of all SRs and RCTs included in this review [see Additional file 2 and 3 for SRs and RCTs, respectively]. The most common measure of intervention success was the amount of weight lost. For a summary of interventions included in this review, see Additional file 4.

Lifestyle interventions

Lifestyle interventions were evaluated in 2 SRs [32, 33] and 11 RCTs [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44] and were found to be largely effective at improving body weight and related measures in overweight and obese individuals. Specifically, interventions that included diet plus exercise or diet plus exercise plus behavioural/psychological components had consistently positive outcomes. Mental health was assessed in a single SR [33], which reported quality of life improvements following a lifestyle intervention. A single RCT [40] evaluated eating disorders outcomes from a lifestyle intervention for weight loss. In this study, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) was prescribed to obese patients with BED in combination with a low-energy-density diet or general nutrition counselling. Both groups had significant reductions in binge eating, and at 12-month follow-up, had significant improvements in behavioural and attitudinal features of BED. No adverse effects were reported.

Dietary interventions

Two SRs [45, 46] and 5 RCTs [47,48,49,50,51] evaluated low-energy diets for weight loss. Weight loss was reported in studies in which participants received very-low-calorie ketogenic diets, high-protein diets or portion-controlled diets, although in most cases this effect was not sustained over longer (12-month) follow-up periods. Increased fruit and vegetable consumption, low carbohydrate diets and a ready-to-eat cereal snack replacement were ineffective as weight loss interventions. Physical adverse effects were reported in only a single study in which participants received very-low-calorie ketogenic diets, and these effects ceased when a normal diet was resumed. Only a single RCT [48] assessed mental health outcomes associated with dietary interventions for weight loss. This study compared the meal replacement Optifast to a conventional reduced-fat diet, and reported significant quality of life improvements in both groups. There were no studies reporting eating disorders outcomes from dietary interventions for weight loss.

Exercise

Exercise was prescribed both on its own and in combination with behavioural and dietary interventions within a lifestyle intervention. The intensity, frequency and duration of the program were important parts of the exercise prescription. Weight loss was reported in one SR [52] and all but one of the 8 RCTs [53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60] evaluating exercise interventions. A number of these studies also reported favourable changes in body composition, such as reductions in body fat, and no adverse effects were reported. Only a single RCT [58] assessed mental health outcomes associated with exercise interventions for weight loss. In this study, quality of life scores improved in moderate- and high-intensity exercise groups compared with no-exercise controls. There were no studies reporting eating disorders outcomes from exercise and physical activity interventions for weight loss.

Behavioural and psychological Interventions

Weight loss was reported, to varying degrees, in the majority of the SRs [61,62,63,64,65,66,67] and RCTs [68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81] evaluating behavioural and psychological interventions. Interventions producing positive effects on weight loss included lifestyle counselling, self-help CBT, and a number of technology-based behavioural interventions, while mixed outcomes occurred following behavioural weight loss or management programmes (including commercially available programmes), mindfulness based interventions and motivational interviewing interventions. A subset of studies targeted obese patients with binge eating disorder. Of these, motivational interviewing yielded reductions in weight, while CBT had mixed outcomes depending on the type: standard and virtual-reality enhanced CBT, but not self-help CBT, produced weight loss. No adverse effects were reported.

Mental health outcomes were evaluated in three RCTs. One RCT [70] reported quality of life improvements in participants in standard and acceptance-based behavioural interventions, with no significant difference between groups. Two RCTs assessed changes in depression symptoms with weight loss treatments targeting obese patients with binge eating disorder. One study [81] reported an improvement in depression symptoms with a motivational-interviewing weight loss intervention that was statistically greater than controls, while the second [72] reported a similar improvement with a self-help CBT intervention, however an improvement was observed in the control group as well.

Eating disorders outcomes were evaluated in 5 RCTs, and all reported positive outcomes. One study [77] reported improved cognitive restraint and control over eating after participation in a 3-year lifestyle intervention which included healthy diet and exercise counselling. Four studies reported reductions in binge eating episodes following standard CBT [71], self-help CBT [72], virtual-reality enhanced CBT [69], motivational interviewing [81] and behavioural weight loss [61]. Behavioural weight loss and standard CBT also led to significantly greater remission from binge eating compared with participants receiving a control intervention.

Pharmacological interventions

Seven SRs [82,83,84,85,86,87,88] and 33 RCTs [89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122] evaluated exclusively pharmacological interventions for weight loss, and 13 RCTs evaluated pharmacotherapy as an adjunct to other interventions. Registered medicines, including anorectics, antidepressants, anticonvulsants and antidiabetics, were highly effective at reducing weight. However, all but one study also reported adverse effects that ranged from mild to severe. In contrast, listed “complimentary” medicines were less effective (less than half of all studies reported positive weight loss outcomes) and also reported fewer adverse effects (less than half of all studies reported adverse effects).

Pharmacotherapies delivered alone led to improvements in quality of life, depression and anxiety (diethylpropion, fenproporex, mazindol, fluoxetine and sibutramine) as well as mood, fatigue and confusion (lipid dietary supplement), although one substance (the anticonvulsant zonisamide) led to a worsening of anxiety, depression, attention, concentration and memory.

Pharmacotherapies delivered as an adjunct to behavioural and psychological interventions led to improvements in quality of life (bupropion/naltrexone plus behavioural modification [111]) and depression symptoms (self-help CBT plus sibutramine [123]).

Eating disorders were evaluated in two RCTs assessed. The first study [114] prescribed the antidepressant medication bupropion to obese women with BED and reported that medication did not improve binge eating, food cravings or associated eating disorders features relative to placebo. The second study [106] was the first to prescribe the endocannabinoid medication rimonabant to obese patients with BED. The treatment group had a significantly greater reduction in scores on the Binge Eating Scale compared with placebo controls; however, this change was not likely to be clinically significant.

Bariatric surgery

Nine SRs [124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132] and 6 RCTs [133,134,135,136,137,138] evaluating exclusively surgical interventions for weight loss were included in this review. Most SRs (7 of 9) assessed outcomes from multiple surgical procedures, and a subset of these pooled outcomes across procedures. Compared with non-surgical interventions, bariatric surgery produced significantly greater reductions in body weight, fat mass and BMI across all studies, regardless of procedure type. However, complications were reported in all studies, and ranged from short-term and minor to long-term and severe (requiring reoperation or causing death). Gastric bypass procedures were generally associated with the greatest improvements in weight-related outcomes, but also had the highest complication and mortality rates.

Mental health and quality of life were the primary focus of three SRs [127,128,129], and the secondary focus of one SR [124] and three RCTs [136,137,138]. These studies reported improvements in quality of life across treatment groups (sleeve gastrectomy and RYGB [136]; RYGB banded and unbanded [124]) as well as in specific treatment groups (duodenal switch outperforming gastric bypass) [137]. One study [138] also reported improvements in psychosocial functioning following gastric bypass and duodenal switch. One SR [127] (assessing 3 RCTs) reported that bariatric surgery was associated with lower rates and fewer symptoms of mental health conditions. In particular, depression was reduced following bariatric surgery in 11 of 12 studies (two of which were RCTs), while rates of alcohol abuse increased relative to similar populations treated non-operatively. A second SR [128] (assessing 19 RCTs) reported a similar decrease in postoperative depressive symptoms along with improvements in anxiety. However, long-term outcomes were mixed, with some studies reporting an improvement in depressive symptoms lasting upwards of 4 years, while other studies reported an initial postoperative benefit followed by a gradual decline. A third SR and meta-analysis [129] (assessing 21 RCTs) compared mental health outcomes of bariatric surgery using a specific assessment tool (the Short-Form 36). This study reported a significant, consistent and large-magnitude improvement in mental health quality of life following bariatric surgery at 1-year follow-up.

Improvements in eating disorder outcomes were reported in two SRs [128] [127]. One SR [128] (assessing 19 RCTs) reported overall improvements in eating behaviour and body image following bariatric surgery for weight loss in morbidly obese individuals, but noted that not all bariatric surgery patients experienced improvements in mental health. The second SR [127] (assessing three RCTs) reported a reduction in binge eating episodes up to two years post-surgery, followed by an increase at further time points.

Other approaches

While lifestyle interventions, pharmacotherapy and surgery remain the primary approaches for treating overweight and obesity, one SR [139] and 10 recent RCTs [140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149] have also trialled traditional Chinese medicine, bright light therapy, e-therapies and self-motivation for change through the use of pedometers or self-weighing. In comparison to the other interventions evaluated in this review, the evidence base supporting these interventions were limited (one to two studies in each case). Positive reductions in weight-related outcomes were reported in each intervention, although effect sizes varied. The single RCT [142] assessing a mental health outcome reported improvements in self-efficacy in participants receiving auricular acupressure. None of the included studies reported on eating disorders outcomes or adverse effects.

Treatment for adolescents

Reduced energy consumption and increased physical activity were the basis for obesity interventions for adolescents, as they were for adults. Pharmacological and surgical interventions were considered in more severe or treatment-resistant cases. Four SRs [150,151,152,153] and 13 [154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166] RCTs evaluated weight loss interventions targeting adolescents and reported predominantly positive effects on body weight and related measures. The only trialled intervention that did not reduce weight or a related measure was dance-based exergaming [163]. A number of studies reported significant short-term results that dissipated at longer-term follow-ups. Adverse effects, ranging from mild to severe, were reported in two SRs [150, 153] on bariatric surgery and one RCT [161] prescribing the glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist exanitide to severely obese patients.

One SR and 6 RCTs evaluated mental health and eating disorders outcomes. Quality of life improved following adjustable gastric banding [153] and combined CBT and exercise [160], while psychosocial functioning and body image improved following exercise interventions (cycling exercise [158] and dance based exergaming [163]). Combined diet, exercise and behavioural/psychological interventions led to improvements in depressive symptoms [165], improved body satisfaction and decreased internalization of female norms [157]. One RCT [155] assigned behavioural weight loss plus an anorectic (sibutramine) to ethnically diverse obese adolescents with and without binge eating behaviours, and reported an improvement in cognitive restraint and disinhibition (loss of control over eating) in individuals with and without initial binge eating behaviours.

Discussion

Numerous treatment strategies exist to assist people in losing weight. Consistent with the literature [58, 167, 168], lifestyle interventions incorporating dietary, exercise and behavioural or psychological components were the most commonly recommended first-line approach, with escalation to pharmacotherapy and bariatric surgery in more severe or treatment-resistant cases. Bariatric surgery and registered medicines consistently reduced weight but were also associated with adverse effects that ranged from mild to severe, while exercise, dietary interventions and behavioural/psychological interventions produced mixed weight loss outcomes but had few adverse effects. Psychological and eating disorder outcomes were infrequently measured (6 of 31 SRs and 31 of 101 RCTs), but where reported, tended to improve alongside weight loss. Specifically, improvements in quality of life, and in some cases depression, were reported in a subset of studies of all intervention types, while improvements in eating disorder symptoms were reported consistently only in interventions incorporating behavioural or psychological treatments. While our review did not explicitly evaluate the factors contributing to psychological improvements, previous studies have implicated weight loss as a key factor in determining changes in psychological state [169,170,171], with the greatest improvements in psychosocial functioning occurring in individuals experiencing the greatest weight loss [172]. Since body image dissatisfaction, weight-related stigmatization and decreased self-esteem are risk factors for depression [173], it follows that interventions that reduce body weight in obese individuals may also lead to improvements in body satisfaction and other related measures of well-being. Given the reciprocal relationship between obesity and mental health and the benefits of behavioural and psychological interventions on eating disorders outcomes, overweight and obesity interventions that incorporate these components would provide a more balanced approach than the traditional focus on weight loss alone.

Concerns have previously been raised that dieting may precipitate eating disorders in overweight and obese individuals [174], however, our findings suggest that professionally administered weight-loss programmes do not increase the risk or symptoms of eating disorders. In contrast, a large body of evidence [175,176,177] reports harms from unhealthy dieting behaviours, which confer a 5- to 18-fold risk for development of eating disorders. It is important that clinicians are aware of the increased risk for harm in individuals engaging in unhealthy dietary practices, and monitor individuals to ensure that healthy diets do not transition into unhealthy diets.

In Australia, the use of surgical procedures to treat obesity has risen dramatically in recent years [178]. Consistent with recent obesity guidelines (e.g., NHMRC, 2013 [179]) our review found bariatric surgery to be the most effective intervention for sustained weight loss, and the majority of studies that included an assessment of psychological outcomes reported improvements, primarily in quality of life and depression symptoms. However, this benefit is not universal, and approximately 20% of patients undergoing bariatric surgery fail to achieve clinically significant weight loss or experience a worsening in psychological outcomes [128, 180, 181]. For certain individuals who lose large amounts of weight, loose, sagging and excess skin may contribute to worsening body image. For example, one study found that over two thirds of post-bariatric surgery patients viewed the development of excess skin to be a negative outcome of treatment, and for some, a motivator to seek plastic surgery [182]. Further, a growing literature suggests that suicide risk is substantially elevated in patients following bariatric surgery [183,184,185]. Increased suicidality in this population is strongly associated with depressive symptoms [186], and obese patients who seek surgery have a higher incidence of psychological distress when compared to obese patients who do not seek surgery [187] or seek less invasive forms of treatment [188]. Despite this concerning association, suicidality was not evaluated or reported on in any of the studies included in this review.

A recent Australian study of bariatric surgery candidates reported that 13.5% of individuals met the DSM-IV criteria for BED [189], while subthreshold disordered eating behaviours in the pre-surgical population were anticipated to exceed these rates [190, 191]. Additionally, disordered eating and BED pre-surgery are associated with poor weight loss outcomes, surgical complications and psychological distress [190,193,, 192–194]. For individuals without a pre-existing eating disorder, the development of eating disorders following surgery is an uncommon but serious postoperative issue that requires particular attention by practitioners recommending or performing these procedures [195]. A small body of literature supports the use of behavioural and cognitive approaches for patients who develop symptoms of anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa [196,197,198], but clinicians should be aware of the difficulties they may encounter when treating post-bariatric eating pathologies. These include the challenges of navigating healthy eating behaviours in patients facing postsurgical food intolerance, fear of gaining weight, and intense management of weight and body image concerns [199]. Certain postoperative symptoms may lead patients to engage in restrictive or compensatory behaviours to mitigate discomfort from consumption of foods that are difficult to tolerate post-operatively [200]. For example, post-operative patients may adopt vomiting behaviour after meals to reduce discomfort caused by consuming newly indigestible foods, or as a means of accelerating weight loss [200]. These factors make it challenging to distinguish between normal post-surgery eating behaviours and eating pathology, since many such changes in eating behaviour are necessitated by the surgery and even encouraged by clinicians [195, 201]. In light of these behaviours and the increased vulnerability of the post-surgical population, clinicians should ensure that long-term follow-ups include an assessment of the motivations for abnormal eating behaviours, separating behaviours motivated by physical discomfort from behaviours motivated by weight and shape concerns.

Future research should endeavour to evaluate and develop a more comprehensive metric of treatment success than BMI or body composition measures alone. There is presently a lack of consensus on what an ‘ideal’ BMI is, particularly for individuals losing large amounts of weight [202, 203], and the emphasis that is placed on external measures of health such as BMI may detract from other important measures of health such as physical activity and well-being [204]. The development of standardized tools for eating disorders assessment in the weight loss context and the identification of shared modifiable risk factors for both conditions would contribute to greater identification of disordered eating symptoms and the delivery of more targeted interventions.

Limitations of this review

The limitations in this review should be taken into account when interpreting outcomes. These include: 1) the RCTs included in evaluated SRs were often highly heterogeneous, precluding pooling for meta-analysis in studies that included these [83]; 2) study outcomes were at times inconsistent [67, 83, 125]; 3) some studies contained a moderate to high risk of bias due to lack of double-blinding and inappropriate or poorly described methods of randomization; and 4) many studies used small, predominantly female and Caucasian samples, limiting generalisability to the broader population. Additionally, this review was limited to a qualitative summary of outcomes reported by original study authors and, by virtue of strict inclusion criteria, may have missed relevant studies that have not yet been published, were published in languages other than English or published prior to 2011. By focusing on uncomplicated obesity, our review may also have missed key studies that explored outcomes in individuals presenting with physical or psychological comorbidities.

Conclusions and recommendations

There are a number of evidence-based strategies for weight loss, and many of these have the additional benefit of improving quality of life, depression and unhealthy eating behaviours. The weight loss strategy that is most effective will depend on an individual’s unique needs and the characteristics of their illness. These include the severity of their obesity, their treatment history, their history of disordered eating or psychological comorbidities, as well as their willingness to manage adverse effects from treatment. Bariatric surgeries lead to the greatest and most persistent reductions in weight, but are frequently accompanied by adverse effects that range from mild to severe. In contrast, interventions incorporating behavioural or psychological components are less efficacious for weight loss, overall, but cause no adverse effects while leading to improvements in psychological well-being and eating disorders symptomatology. Given the interconnected nature of obesity, mental health and eating disorders, we suggest that weight-loss interventions focus simultaneously on two targets: an evidence-based component that targets weight loss (lifestyle interventions, medications or surgery, dependent on the individual’s circumstance) alongside an evidence-based behavioural or mental health component that focuses on psychological well-being. This second component should include an ongoing evaluation of disordered eating behaviours and psychopathologies.

There is an increased need for prevention and treatment interventions that target the broad spectrum of weight-related disorders. This necessarily requires dialogue and collaboration between professionals in obesity and eating disorders sectors, as well as the involvement of stakeholders at all levels of community and government. Treatment strategies for overweight and obesity should be evidence based and comprehensive, taking into account a broader range of health outcomes than weight or BMI alone [205]. Given the benefits of behavioural and psychological interventions on eating disorders outcomes and weight loss, weight loss interventions should incorporate these components into a more holistic program of care. Treatments should follow a chronic disease model of care that progresses from the use of micro-environmental and lifestyle interventions through to more intensive interventions alongside the severity of obesity [206]. Existing and new treatments should include long-term follow ups and maintenance sessions which incorporate routine assessments of psychological well-being alongside weight-related measures. Importantly, psychological and physical comorbidities should be managed concurrently with weight to maximize outcomes in both physical health and quality of life [207], and when disordered eating is detected, stabilization of eating disorders symptoms should precede and run alongside the weight loss program. This review provides support for ua multidisciplinary treatment approach that takes into account the various factors underlying obesity and eating disorders, as well as the factors confounding treatment outcomes.

Abbreviations

- BED:

-

Binge eating disorder

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BN:

-

Bulimia nervosa

- CBT:

-

Cognitive behavioural therapy

- OQAQ:

-

Overview quality assessment questionnaire

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- RYGB:

-

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

- SR:

-

Systematic review

- TGA:

-

Therapeutic goods administration

References

Haby MM, Markwick A, Peeters A, Shaw J, Vos T. Future predictions of body mass index and overweight prevalence in Australia, 2005–2025. Health Promot Int. 2012;27:250–60.

Walls HL, Magliano DJ, Stevenson CE, Backholer K, Mannan HR, Shaw JE, Peeters A. Projected progression of the prevalence of obesity in Australia. Obesity. 2012;20:872–8.

Hay PPJ, Girosi F, Mond J. Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of DSM-5 eating disorders in the Australian population. J Eat Disord. 2015;3:1–7.

Hay PPJ, Buttner P, Mond J, Paxton SJ, Rodgers B, Quirk F, Darby AM. Quality of life, course and predictors of outcomes in community women with EDNOS and common eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2010;18:281–95.

Darby A, Hay PPJ, Mond J, Quirk F, Buttner P, Kennedy L. The rising prevalence of comorbid obesity and eating disorder behaviors from 1995 to 2005. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42:104–8.

Neumark-Sztainer DR: Preventing the broad spectrum of weight-related problems: Working with parents to help teens achieve a healthy weight and a positive body image. J Nutr Educ Behav 2005;37

Slevec J, Tiggemann M. Media exposure, body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating in middle-aged women: A test of the sociocultural model of disordered eating. Psychol Women Q. 2011;35:617–27.

Watson R, Vaughn LM. Limiting the effects of the media on body image: Does the length of a media literacy intervention make a difference? Eat Disord. 2006;14:385–400.

Evans J, Rich E, Holroyd R. Disordered eating and disordered schooling: What schools do to middle class girls. Br J Sociol Educ. 2004;25:123–42.

Schwartz MB, Henderson KE. Does obesity prevention cause eating disorders? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:784–6.

Bombak AE: The contribution of applied social sciences to obesity stigma-related public health approaches. J Obes. 2014.

Lewis S, Thomas SL, Hyde J, Castle D, Blood RW, Komesaroff PA. I don’t eat a hamburger and large chips every day!” A qualitative study of the impact of public health messages about obesity on obese adults. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:309.

Puhl RM, Heuer CA. Obesity stigma: Important considerations for public health. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1019–28.

Sánchez-Carracedo D, Neumark-Sztainer D, López-Guimerà G. Integrated prevention of obesity and eating disorders: Barriers, developments and opportunities. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15:1–15.

Striegel-Moore RH, Dohm FA, Pike KM, Wilfley DE, Fairburn CG. Abuse, bullying, and discrimination as risk factors for binge eating disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1902–7.

Jackson TD, Grilo CM, Masheb RM. Teasing history, onset of obesity, current eating disorder psychopathology, body dissatisfaction, and psychological functioning in binge eating disorder. Obes Res. 2000;8:451–8.

van den Berg P, Neumark-Sztainer D. Fat `n happy 5 years later: Is it bad for overweight girls to like their bodies? J Adolesc Heal. 2007;41:415–7.

Bryn Austin S. The blind spot in the drive for childhood obesity prevention: Bringing eating disorders prevention into focus as a public health priority. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:1–5.

Daee A, Robinson P, Lawson M, Turpin JA, Gregory B, Tobias JD. Psychologic and physiologic effects of dieting in adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2002;95:1032–41.

Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Guo J, Story M, Haines J, Eisenberg M. Obesity, disordered eating, and eating disorders in a longitudinal study of adolescents: How do dieters fare 5 years later? J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:559–68.

O’Dea JA. Prevention of child obesity: “First, do no harm.”. Health Educ Res. 2005;20:259–65.

Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Doll HA, Norman P, O’Connor M. The natural course of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder in young women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:659–65.

Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:348–58.

Bulik CM, Sullivan PF, Kendler KS. Medical and psychiatric morbidity in obese women with and without binge eating. Obes Binge Eat. 2002;32:72–8.

Faulconbridge LF, Wadden TA, Thomas JG, Jones-Corneille LR, Sarwer DB, Fabricatore AN, Faulconbridge LF. Changes in depression and quality of life in obese individuals with binge eating disorder: Bariatric surgery vs. lifestyle modification. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9:790–6.

Hill AJ. Obesity and eating disorders. Obes Rev. 2007;8:151–5.

Walls HL, Peeters A, Proietto J, McNeil JJ. Public health campaigns and obesity - a critique. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:136.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Grp P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Phys Ther. 2009;89:873–80.

Oxman AD, Guyatt GH. Validation of an index of the quality of review articles. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44:1271–8.

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJM, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12.

NHMRC. Additional Levels of Evidence and Grades for Recommendations for Developers of Guidelines. 2009.

Gudzune KA, Doshi RS, Mehta AK, Chaudhry ZW, Jacobs DK, Vakil RM, Lee CJ, Bleich SN, Clark JM. Efficacy of commercial weight-loss programs: An updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:501–12.

Baillot A, Romain AJ, Boisvert-Vigneault K, Audet M, Baillargeon JP, Dionne IJ, Valiquette L, Chakra CNA, Avignon A, Langlois MF. Effects of lifestyle interventions that include a physical activity component in class II and III obese individuals: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2015;10:1–33.

Anderson JW, Reynolds LR, Bush HM, Rinsky JL, Washnock C. Effect of a behavioral/nutritional intervention program on weight loss in obese adults: A randomized controlled trial. Postgrad Med. 2011;123:205–13.

Carraça EV, Markland D, Silva MN, Coutinho SR, Vieira PN, Minderico CS, Sardinha LB, Teixeira PJ. Physical activity predicts changes in body image during obesity treatment in women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44:1604–12.

Christensen JR, Faber A, Ekner D, Overgaard K, Holtermann A, Søgaard K. Diet, physical exercise and cognitive behavioral training as a combined workplace based intervention to reduce body weight and increase physical capacity in health care workers - a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:671.

Foster GD, Shantz KL, Vander Veur SS, Oliver TL, Lent MR, Virus A, Szapary PO, Rader DJ, Zemel BS, Gilden-Tsai A. A randomized trial of the effects of an almond-enriched, hypocaloric diet in the treatment of obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96:249–54.

Gorin AA, Raynor HA, Fava J, Maguire K, Robichaud E, Trautvetter J, Crane M, Wing RR. Randomized controlled trial of a comprehensive home environment-focused weight-loss program for adults. Heal Psychol Off J Div Heal Psychol Am Psychol Assoc. 2013;32:128–37.

Malkina-Pykh IG. Effectiveness of rhythmic movement therapy for disordered eating behaviors and obesity. Span J Psychol. 2012;15:1371–87.

Masheb RM, Grilo CM, Rolls BJ. A randomized controlled trial for obesity and binge eating disorder: Low-energy-density dietary counseling and cognitive-behavioral therapy. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49:821–9.

Nackers LM, Middleton KR, Dubyak PJ, Daniels MJ, Anton SD, Perri MG. Effects of prescribing 1,000 versus 1,500 kilocalories per day in the behavioral treatment of obesity: A randomized trial. Obesity. 2013;21:2481–7.

Almeida FA, You W, Harden SM, Blackman KCA, Davy BM, Glasgow RE, Hill JL, Linnan LA, Wall SS, Yenerall J, Zoellner JM, Estabrooks PA. Effectiveness of a worksite-based weight loss randomized controlled trial: The worksite study. Obesity. 2015;23:737–45.

Ströbl V, Knisel W, Landgraf U, Faller H. A combined planning and telephone aftercare intervention for obese patients: Effects on physical activity and body weight after one year. J Rehabil Med. 2013;45:198–205.

Maddison R, Foley L, Mhurchu CN, Jiang Y, Jull A, Prapavessis H, Hohepa M, Rodgers A. Effects of active video games on body composition: A randomized. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:156–63.

Naude CE, Schoonees A, Senekal M, Young T, Garner P, Volmink J. Low carbohydrate versus isoenergetic balanced diets for reducing weight and cardiovascular risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9.

Kaiser KA, Brown AW, Brown MMB, Shikany JM, Mattes RD, Allison DB. Increased fruit and vegetable intake has no discernible effect on weight loss: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100:567–76.

Griffin HJ, Cheng HL, O’Connor HT, Rooney KB, Petocz P, Steinbeck KS. Higher protein diet for weight management in young overweight women: A 12-month randomized controlled trial. Diabetes, Obes Metab. 2013;15:572–5.

Khoo J, Ling PS, Chen RYT, Ng KK, Tay TL, Tan E, Cho LW, Cheong M. Comparing the effects of meal replacements with an isocaloric reduced-fat diet on nutrient intake and lower urinary tract symptoms in obese men. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2014;27:219–26.

Matthews A, Hull S, Angus F, Johnston KL. The effect of ready-to-eat cereal consumption on energy intake, body weight and anthropometric measurements: Results from a randomized, controlled intervention trial. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2012;63:107–13.

Moreno B, Bellido D, Sajoux I, Goday A, Saavedra D, Crujeiras AB, Casanueva FF. Comparison of a very low-calorie-ketogenic diet with a standard low-calorie diet in the treatment of obesity. Endocrine. 2014;47:793–805.

Poelman MP, de Vet E, Velema E, de Boer MR, Seidell JC, Steenhuis IHM. PortionControl@HOME: Results of a randomized controlled trial evaluating the effect of a multi-component portion size intervention on portion control behavior and body mass index. Ann Behav Med 2014:18–28.

Baillot A, Audet M, Baillargeon JP, Dionne IJ, Valiquette L, Rosa-Fortin MM, Abou Chakra CN, Comeau E, Langlois MF. Impact of physical activity and fitness in class II and III obese individuals: A systematic review. Obes Rev. 2014;15:721–39.

Keating SE, Machan EA, O’Connor HT, Gerofi JA, Sainsbury A, Caterson ID, Johnson NA. Continuous exercise but not high intensity interval training improves fat distribution in overweight adults. J Obes. 2014;2014:25–7.

Donnelly JE, Honas JJ, Smith BK, Mayo MS, Gibson CA, Sullivan DK, Lee J, Herrmann SD, Lambourne K, Washburn RA. Aerobic exercise alone results in clinically significant weight loss for men and women: Midwest exercise trial 2. Obesity. 2013;21:E219–28.

Sanal E, Ardic F, Kirac S. Effects of aerobic or combined aerobic resistance exercise on body composition in overweight and obese adults: Gender differences. A randomized intervention study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2013;49:1–11.

Willis LH, Slentz CA, Bateman LA, Shields TA, Piner LW, Bales CW, Houmard JA, Kraus WE. Effects of aerobic and/or resistance training on body mass and fat mass in overweight or obese adults. J Appl Physiol. 2012;113:1831–7.

Sijie T, Hainai Y, Fengying Y, Jianxiong W. High intensity interval exercise training in overweight young women. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2012;52:255–62.

Reichkendler MH, Rosenkilde M, Auerbach PL, Agerschou J, Nielsen MB, Kjaer A, Hoejgaard L, Sjodin A, Ploug T, Stallknecht B. Only minor additional metabolic health benefits of high as opposed to moderate dose physical exercise in young, moderately overweight men. Obesity. 2014;22:1220–32.

Ross R, Hudson R, Stotz PJ, Lam M. Effects of exercise amount and intensity on abdominal obesity and glucose tolerance in obese adults: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:325–34.

Cakmakci O. The effect of 8 week pilates exercise on body composition in obese women. Coll Antropol. 2011;35:1045–50.

Booth HP, Prevost TA, Wright AJ, Gulliford MC. Effectiveness of behavioural weight loss interventions delivered in a primary care setting: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Fam Pract. 2014;31:643–53.

Yoong SL, Carey M, Sanson-Fisher R, Grady A. A systematic review of behavioural weight-loss interventions involving primary-care physicians in overweight and obese primary-care patients (1999–2011). Public Health Nutr. 2012;16:1–17.

Hutchesson MJ, Hulst J, Collins CE. Weight management interventions targeting young women: A systematic review. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113:795–802.

Johns DJ, Hartmann-Boyce J, Jebb SA, Aveyard P. Diet or exercise interventions vs combined behavioral weight management programs: A systematic review and meta-analysis of direct comparisons. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114:1557–68.

Wadden TA, Butryn ML, Hong PS, Tsai AG. Behavioral treatment of obesity in patients encountered in primary care settings: A systematic review: Editorial comment. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2015;70:174–5.

Olson KL, Emery CF. Mindfulness and weight loss: A systematic review. Psychosom Med. 2015;77:59–67.

Barnes RD, Ivezaj V. A systematic review of motivational interviewing for weight loss among adults in primary care. Obes Rev. 2015;16:304–18.

Burke LE, Wang J. Treatment strategies for overweight and obesity. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2011;43:368–75.

Cesa GL, Manzoni GM, Bacchetta M, Castelnuovo G, Conti S, Gaggioli A, Mantovani F, Molinari E, Cárdenas-López G, Riva G. Virtual reality for enhancing the cognitive behavioral treatment of obesity with binge eating disorder: Randomized controlled study with one-year follow-up. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e113.

Forman EMM, Butryn MLL, Juarascio ASS, Bradley LEE, Lowe MRR, Herbert JDD, Shaw JAA. The mind your health project: A randomized controlled trial of an innovative behavioral treatment for obesity. Obesity. 2013;21:1119–26.

Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT, Gueorguieva R, White MA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, behavioral weight loss, and sequential treatment for obese patients with binge-eating disorder: A randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79:675–85.

Grilo CM, White MA, Gueorguieva R, Barnes RD, Masheb RM. Self-help for binge eating disorder in primary care: A randomized controlled trial with ethnically and racially diverse obese patients. Behav Res Ther. 2013;51:855–61.

Hunt K, Wyke S, Gray CM, Anderson AS, Brady A, Bunn C, Donnan PT, Fenwick E, Grieve E, Leishman J, Miller E, Mutrie N, Rauchhaus P, White A, Treweek S. A gender-sensitised weight loss and healthy living programme for overweight and obese men delivered by Scottish Premier League football clubs (FFIT): A pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1211–21.

Jakicic JM, Tate DF, Lang W, Davis KK, Polzien K, Rickman AD, Erickson K, Neiberg RH, Finkelstein EA. Effect of a stepped-care intervention approach on weight loss in adults: A randomized clinical trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2012;307:2617–26.

Johnston CA, Rost S, Miller-Kovach K, Moreno JP, Foreyt JP. A randomized controlled trial of a community-based behavioral counseling program. Am J Med 2013;126.

Nanchahal K, Power T, Holdsworth E, Hession M, Sorhaindo A, Griffiths U, Townsend J, Thorogood N, Haslam D, Kessel A, Ebrahim S, Kenward M, Haines A. A pragmatic randomised controlled trial in primary care of the Camden Weight Loss (CAMWEL) programme. BMJ Open. 2012;2:1–16.

Nurkkala M, Kaikkonen K, Vanhala ML, Karhunen L, Kernen AM, Korpelainen R. Lifestyle intervention has a beneficial effect on eating behavior and long-term weight loss in obese adults. Eat Behav. 2015;18:179–85.

Pellegrini CA, Verba SD, Otto AD, Helsel DL, Davis KK, Jakicic JM. The comparison of a technology-based system and an in-person behavioral weight loss intervention. Obesity. 2012;20:356–63.

Pinto AM, Fava JL, Hoffmann DA, Wing RR. Combining behavioral weight loss treatment and a commercial program: A randomized clinical trial. Obesity. 2013;21:673–80.

Spring B, Duncan JM, Janke EA, Kozak AT, McFadden HG, DeMott A, Pictor A, Epstein LH, Siddique J, Pellegrini CA, Buscemi J, Hedeker D. Integrating technology into standard weight loss treatment: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:105–11.

Barnes RD, White MA, Martino S, Grilo CM. A randomized controlled trial comparing scalable weight loss treatments in primary care. Obesity. 2014;22:2508–16.

Astell KJ, Mathai ML, Su XQ. Plant extracts with appetite suppressing properties for body weight control: A systematic review of double blind randomized controlled clinical trials. Complement Ther Med. 2013;21:407–16.

Jurgens T, Whelan A, Killian L, Doucette S, Kirk S, Foy E, Jurgens TM, Whelan AM, Killian L, Doucette S, Kirk S, Foy E. Green tea for weight loss and weight maintenance in overweight or obese adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012.

Onakpoya I, Posadzki P, Ernst E. Chromium supplementation in overweight and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Obes Rev. 2013;14:496–507.

Onakpoya I, Posadzki P, Ernst E. The efficacy of glucomannan supplementation in overweight and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Am Coll Nutr. 2014;33:70–8.

Pathak K, Soares MJ, Calton EK, Zhao Y, Hallett J. Vitamin D supplementation and body weight status: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. 2014;15:528–37.

Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Long-term drug treatment for obesity: A systematic and clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311:74–86.

Nigro SC, Luon D, Baker WL. Lorcaserin: A novel serotonin 2C agonist for the treatment of obesity. Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29:839–48.

Blomquist KK, Grilo CM. Predictive significance of changes in dietary restraint in obese patients with binge eating disorder during treatment. Int J Eat Disord. 2011;44:515–23.

Allison DB, Gadde KM, Garvey WT, Peterson CA, Schwiers ML, Najarian T, Tam PY, Troupin B, Day WW. Controlled-release phentermine/topiramate in severely obese adults: A randomized controlled trial (EQUIP). Obesity. 2011;20:330–42.

Aronne LJ, Wadden TA, Peterson C, Winslow D, Odeh S, Gadde KM. Evaluation of phentermine and topiramate versus phentermine/topiramate extended-release in obese adults. Obesity. 2013;21:2163–71.

Baer DJ, Stote KS, Paul DR, Harris GK, Rumpler WV, Clevidence BA. Whey protein but not soy protein supplementation alters body weight and composition in free-living overweight and obese adults. J Nutr. 2011;141:1489–94.

Bays HE, Weinstein R, Law G, Canovatchel W. Canagliflozin: Effects in overweight and obese subjects without diabetes mellitus. Obesity. 2014;22:1042–9.

DeFina L, Marcoux L. Effects of omega-3 supplementation in combination with diet and exercise on weight loss and body composition. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:455–62.

Gadde KM, Kopping MF, Wagner R, Yonish GM, Allison DB, Bray GA. Zonisamide for weight reduction in obese adults. J Am Med Assoc. 2013;310:637–8.

Georg Jensen M, Kristensen M, Astrup A. Effect of alginate supplementation on weight loss in obese subjects completing a 12-wk energy-restricted diet: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96:5–13.

Grube B, Chong P-W, Lau K-Z, Orzechowski H-D. A natural fiber complex reduces body weight in the overweight and obese: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Obesity. 2012;21:58–64.

Harden CJ, Dible VA, Russell JM, Garaiova I, Plummer SF, Barker ME, Corfe BM. Long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation had no effect on body weight but reduced energy intake in overweight and obese women. Nutr Res. 2014;34:17–24.

Grilo CM, Crosby RD, Wilson GT, Masheb RM. 12-month follow-up of fluoxetine and cognitive behavioral therapy for binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80:1108–13.

Grilo CM, White MA. Orlistat with behavioral weight loss for obesity with versus without binge eating disorder: Randomized placebo-controlled trial at a community mental health center serving educationally and economically disadvantaged Latino/as. Behav Res Ther. 2013;51:167–75.

Grilo CM, Masheb RM, White MA, Gueorguieva R, Barnes RD, Walsh BT, McKenzie KC, Genao I, Garcia R. Treatment of binge eating disorder in racially and ethnically diverse obese patients in primary care: Randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial of self-help and medication. Behav Res Ther. 2014;58:1–9.

Jung EY, Cho MK, Hong YH, Kim JH, Park Y, Chang UJ, Suh HJ. Yeast hydrolysate can reduce body weight and abdominal fat accumulation in obese adults. Nutrition. 2014;30:25–32.

Keithley JK, Swanson B, Mikolaitis SL, Demeo M, Zeller JM, Fogg L, Adamji J. Safety and efficacy of glucomannan for weight loss in overweight and moderately obese adults. J Obes. 2013.

Mangine GT, Gonzalez AM, Wells AJ, McCormack WP, Fragala MS, Stout JR, Hoffman JR. The effect of a dietary supplement (N-oleyl-phosphatidyl-ethanolamine and epigallocatechin gallate) on dietary compliance and body fat loss in adults who are overweight: A double-blind, randomized control trial. Lipids Health Dis. 2012;11:127.

Munro IA, Garg ML. Dietary supplementation with long chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and weight loss in obese adults. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2013;7:e173–81.

Pataky Z, Gasteyger C, Ziegler O, Rissanen A, Hanotin C, Golay A. Efficacy of rimonabant in obese patients with binge eating disorder. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2013;121:20–6.

Park S-H, Huh T-L, Kim S-Y, Oh M-R, Tirupathi Pichiah PBB, Chae S-W, Cha Y-S. Antiobesity effect of Gynostemma pentaphyllum extract (actiponin): A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Obesity. 2014;22:63–71.

Pi-Sunyer X, Astrup A, Fujioka K, Greenway F, Halpern A, Krempf M, Lau DCW, le Roux CW, Violante Ortiz R, Jensen CB, Wilding JPH. A randomized, controlled trial of 3.0 mg of liraglutide in weight management. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:11–22.

Poole CN, Roberts MD, Dalbo VJ, Tucker PS, Sunderland KL, DeBolt ND, Billbe BW, Kerksick CM. The combined effects of exercise and ingestion of a meal replacement in conjunction with a weight loss supplement on body composition and fitness parameters in college-aged men and women. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25:51–60.

Rosenblum JL, Castro VM, Moore CE, Kaplan LM. Calcium and vitamin D supplementation is associated with decreased abdominal visceral adipose tissue in overweight and obese adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95:101–8.

Wadden TA, Foreyt JP, Foster GD, Hill JO, Klein S, O’Neil PM, Perri MG, Pi-Sunyer FX, Rock CL, Erickson JS, Maier HN, Kim DD, Dunayevich E. Weight loss with naltrexone SR/bupropion SR combination therapy as an adjunct to behavior modification: The COR-BMOD trial. Obesity. 2011;19:110–20.

Tur JJ, Escudero AJ, Alos MM, Salinas R, Teros E, Soriano JB, Nicola G, Urgelas JR, Pagon A, Cortes B, Gonzalez X, Burguera B. One year weight loss in the TRAMOMTANA study. A randomized controlled trial. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2013;79:791–9.

Wadden TA, Volger S, Sarwer DB, Vetter ML, Tsai AG, Berkowitz RI, Kumanyika S, Schmitz KH, Diewald LK, Barg R, Chittams J, Moore RH, Ph D. A two-year randomized trial of obesity treatment in primary care practice. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1969–79.

White MA, Grilo CM. Bupropion for overweight women with binge-eating disorder: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:400–6.

Huerta AE, Navas-Carretero S, Prieto-Hontoria PL, Martínez JA, Moreno-Aliaga MJMJ. Effects of α-lipoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid in overweight and obese women during weight loss. Obesity. 2015;23:313–21.

Lim SS, Norman RJ, Clifton PM, Noakes M. The effect of comprehensive lifestyle intervention or metformin on obesity in young women. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;21:261–8.

Shin JH, Gadde KM, Østbye T, Bray GA. Weight changes in obese adults 6-months after discontinuation of double-blind zonisamide or placebo treatment. Diabetes, Obes Metab. 2014;16:766–8.

Apovian CM, Aronne L, Rubino D, Still C, Wyatt H, Burns C, Kim D, Dunayevich E. A randomized, phase 3 trial of naltrexone SR/bupropion SR on weight and obesity-related risk factors (COR-II). Obesity. 2013;21:935–43.

Suplicy H, Boguszewski CL, dos Santos CMC, do Desterro de Figueiredo M, Cunha DR, Radominski R. A comparative study of five centrally acting drugs on the pharmacological treatment of obesity. Int J Obes. 2014;38:1097–103.

Sanchez M, Darimont C, Drapeau V, Emady-Azar S, Lepage M, Rezzonico E, Ngom-Bru C, Berger B, Philippe L, Ammon-Zuffrey C, Leone P, Chevrier G, St-Amand E, Marette A, Doré J, Tremblay A. Effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosus CGMCC1.3724 supplementation on weight loss and maintenance in obese men and women. Br J Nutr. 2014;111:1507–19.

Salehpour A, Hosseinpanah F, Shidfar F, Vafa M, Razaghi M, Dehghani S, Hoshiarrad A, Gohari M. A 12-week double-blind randomized clinical trial of vitamin D(3) supplementation on body fat mass in healthy overweight and obese women. Nutr J. 2012;11:78.

Liu AG, Smith SR, Fujioka K, Greenway FL. The effect of leptin, caffeine/ephedrine, and their combination upon visceral fat mass and weight loss. Obesity. 2013;21:1991–6.

Gearhardt AN, White MA, Masheb RM, Morgan PT, Crosby RD, Grilo CM. An examination of the food addiction construct in obese patients with binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45:657–63.

Buchwald H, Buchwald JN, McGlennon TW. Systematic review and meta-analysis of medium-term outcomes after banded Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2014;24:1536–51.

Chang S-H, Stoll CRT, Song J, Varela JE, Eagon CJ, Colditz GA. The effectiveness and risks of bariatric surgery. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:275.

Colquitt JL, Pickett K, Loveman E, Frampton GK. Surgery for weight loss in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;8:CD003641.

Dawes AJ, Maggard-Gibbons M, Maher AR, Booth MJ, Miake-Lye I, Beroes JM, Shekelle PG. Mental health conditions among patients seeking and undergoing bariatric surgery: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;315:150–63.

Kubik JF, Gill RS, Laffin M, Karmali S. The impact of bariatric surgery on psychological health. J Obes. 2013;2013

Magallares A, Schomerus G. Mental and physical health-related quality of life in obese patients before and after bariatric surgery: A meta-analysis. Psychol Heal Med. 2015;20:165–76.

Puzziferri N, Roshek TB, Mayo HG, Gallagher R, Belle SH, Livingston EH. Long-term follow-up after bariatric surgery. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2014;312:934.

Gloy VL, Briel M, Bhatt DL, Kashyap SR, Schauer PR, Mingrone G, Bucher HC, Nordmann AJ. Bariatric surgery versus non-surgical treatment for obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2013;347:f5934.

Trastulli S, Desiderio J, Guarino S, Cirocchi R, Scalercio V, Noya G, Parisi A. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy compared with other bariatric surgical procedures: A systematic review of randomized trials. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9:816–29.

Kehagias I, Karamanakos SN, Argentou M-I, Kalfarentzos F. Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for the management of patients with BMI < 50 kg/m2. Obes Surg. 2011;21:1650–6.

Hedberg J, Sundbom M. Superior weight loss and lower HbA1c 3 years after duodenal switch compared with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass - A randomized controlled trial. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8:338–43.

Zarate X, Arceo-Olaiz R, Montalvo Hernandez J, García-García E, Pablo Pantoja J, Herrera MF. Long-term results of a randomized trial comparing banded versus standard laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9:395–7.

Zhang Y, Zhao H, Cao Z, Sun X, Zhang C, Cai W, Liu R, Hu S, Qin M. A randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy for the treatment of morbid obesity in China: A 5-year outcome. Obes Surg. 2014;24:1617–24.

Sovik TT, Aasheim ET, Taha O, Engstrom M, Fagerland MW, Bjorkman S, Kristinsson J, Birkeland K, Mala T, Olbers T. Weight loss, cardiovascular risk factors, and quality of life after gastric bypass and duodenal switch: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:281–91.

Sovik TT, Karlsson J, Aasheim ET, Fagerland MW, Bjorkman S, Engstrom M, Kristinsson J, Olbers T, Mala T. Gastrointestinal function and eating behavior after gastric bypass and duodenal switch. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9:641–7.

Hutchesson MJ, Rollo ME, Krukowski R, Ells L, Harvey J, Morgan PJ, Callister R, Plotnikoff R, Collins CE. eHealth interventions for the prevention and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2015;16:376–92.

Danilenko KV, Mustafina SV, Pechenkina EA. Bright light for weight loss: Results of a controlled crossover trial. Obes Facts. 2013;6:28–38.

Hsieh CH, Su T-J, Fang Y-W, Chou P-H. Effects of auricular acupressure on weight reduction and abdominal obesity in Asian young adults: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Chin Med. 2011;39:433–40.

Kim D, Ham OK, Kang C, Jun E, Peters G. Effects of auricular acupressure using Sinapsis Alba seeds on obesity and self-efficacy in female college students. Dtsch Zeitschrift fur Akupunkt. 2014;57:22–3.

Yeo S, Kim KS, Lim S. Randomised clinical trial of five ear acupuncture points for the treatment of overweight people. Acupunct Med. 2014;32:132–8.

Napolitano MA, Hayes S, Bennett GG, Ives AK, Foster GD. Using Facebook and text messaging to deliver a weight loss program to college students. Obesity. 2013;21:25–31.

Cayir Y, Aslan SM, Akturk Z. The effect of pedometer use on physical activity and body weight in obese women. Eur J Sport Sci. 2015;15:351–6.

Steinberg DM, Tate DF, Bennett GG, Ennett S, Samuel-Hodge C, Ward DS. The efficacy of a daily self-weighing weight loss intervention using smart scales and e-mail. Obesity. 2013;21:1789–97.

Chambliss HO, Huber RC, Finley CE, McDoniel SO, Kitzman-Ulrich H, Wilkinson WJ. Computerized self-monitoring and technology-assisted feedback for weight loss with and without an enhanced behavioral component. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85:375–82.

Shapiro JR, Koro T, Doran N, Thompson S, Sallis JF, Calfas K, Patrick K. Text4Diet: A randomized controlled study using text messaging for weight loss behaviors. Prev Med (Baltim). 2012;55:412–7.

Sakurai R, Fujiwara Y, Saito K, Fukaya T, Kim MJ, Yasunaga M, Kim H, Ogawa K, Tanaka C, Tsunoda N, Muraki E, Suzuki K, Shinkai S, Watanabe S. Effects of a comprehensive intervention program, including hot bathing, on overweight adults: A randomized controlled trial. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2013;13:638–45.

Black JA, White B, Viner RM, Simmons RK. Bariatric surgery for obese children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2013;14:634–44.

Brufani C, Crino A, Fintini D, Patera PI, Cappa M, Manco M. Systematic review of metformin use in obese nondiabetic children and adolescents. Horm Res Paediatr. 2013;80:78–85.

Bouza C, López-Cuadrado T, Gutierrez-Torres LF, Amate J. Efficacy and safety of metformin for treatment of overweight and obesity in adolescents: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Facts. 2012;5:753–65.

Willcox K, Brennan L. Biopsychosocial outcomes of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in adolescents: A systematic review of the literature. Obes Surg. 2014;24:1510–9.

Berkowitz RI, Wadden TA, Gehrman CA, Bishop-Gilyard CT, Moore RH, Womble LG, Cronquist JL, Trumpikas NL, Levitt Katz LE, Xanthopoulos MS. Meal replacements in the treatment of adolescent obesity: A randomized controlled trial. Obesity. 2011;19:1193–9.

Bishop-Gilyard CT, Berkowitz RI, Wadden TA, Gehrman CA, Cronquist JL, Moore RH. Weight reduction in obese adolescents with and without binge eating. Obesity. 2011;19:982–7.

Brennan L, Walkley J, Wilks R, Fraser SF, Greenway K: Physiological and behavioural outcomes of a randomised controlled trial of a cognitive behavioural lifestyle intervention for overweight and obese adolescents. Obes Res Clin Pract. 7:e23-41.

DeBar LL, Stevens VJ, Perrin N, Wu P, Pearson J, Yarborough BJ, Dickerson J, Lynch F. A primary care-based, multicomponent lifestyle intervention for overweight adolescent females. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e611–20.

Goldfield GSP, Adamo KBP, Rutherford JM, Murray MMA. The effects of aerobic exercise on psychosocial functioning of adolescents who are overweight or obese. J Pediatr Psychol. 2012;37:1136–47.

Hofsteenge GH, Chinapaw MJM, de Waal HA D-v, Weijs PJM. Long-term effect of the Go4it group treatment for obese adolescents: A randomised controlled trial. Clin Nutr. 2014;33:385–91.

Hofsteenge GH, Weijs PJM, de Waal HA D-v, de Wit M, Chinapaw MJM. Effect of the Go4it multidisciplinary group treatment for obese adolescents on health related quality of life: A randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:939.

Kelly AS, Rudser KD, Nathan BM, Fox CK, Metzig AM, Coombes BJ, Fitch AK, Bomberg EM, Abuzzahab MJ. The effect of Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist therapy on body mass index in adolescents with severe obesity. J Am Med Assoc Pediatr. 2013;167:355–60.

Kong APS, Choi KC, Chan RSM, Lok K, Ozaki R, Li AM, Ho CS, Chan MHM, Sea M, Henry CJ, Chan JCN, Woo J. A randomized controlled trial to investigate the impact of a low glycemic index (GI) diet on body mass index in obese adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:180.

Wagener TL, Fedele DA, Mignogna MR, Hester CN, Gillaspy SR. Psychological effects of dance-based group exergaming in obese adolescents. Pediatr Obes. 2012;7:68–75.

Wang S, Yang L, Lu J, Mu Y. High-protein breakfast promotes weight loss by suppressing subsequent food intake and regulating appetite hormones in obese Chinese adolescents. Horm Res Paediatr. 2015;83:19–25.

Toulabi T, Khosh Niyat Nikoo M, Amini F, Nazari H, Mardani M. The influence of a behavior modification interventional program on body mass index in obese adolescents. J Formos Med Assoc. 2012;111:153–9.

Sigal RJ, Alberga AS, Goldfield GS, Prud’homme D, Hadjiyannakis S, Gougeon R, Phillips P, Tulloch H, Malcolm J, Doucette S, Wells GA, Ma J, Kenny GP. Effects of aerobic training, resistance training, or both on percentage body fat and cardiometabolic risk markers in obese adolescents: the healthy eating aerobic and resistance training in youth randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:1006–14.

Fontaine KR, Redden DT, Wang C, Westfall AO, Allison DB. Years of life lost due to obesity. J Am Med Assoc. 2003;289:187–93.

Latner JD, Durso LE, Mond JM. Health and health-related quality of life among treatment-seeking overweight and obese adults: Associations with internalized weight bias. J Eat Disord. 2013;1:3.

Lasikiewicz N, Myrissa K, Hoyland A, Lawton CL. Psychological benefits of weight loss following behavioural and/or dietary weight loss interventions. A systematic research review. Appetite. 2014;72:123–37.

Guisado JA, Vaz FJ, Alarcón J, López-Ibor JJ, Rubio MA, Gaite L. Psychopathological status and interpersonal functioning following weight loss in morbidly obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2002;12:835–40.

Mamplekou E, Komesidou V, Bissias C, Papakonstantinou A, Melissas J. Psychological condition and quality of life in patients with morbid obesity before and after surgical weight loss. Obes Surg. 2005;15:1177–84.

Larsen JK, Geenen R, Van Ramshorst B, Brand N, De Wit P, Stroebe W, Van Doornen LJP. Psychosocial functioning before and after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: A cross-sectional study. Obes Surg. 2003;13:629–36.

Luppino FS, Leonore MW, Bouvy PF, Stijnen T, Cuijpers P, Brenda WJH, Zitman FG. Overweight, obesity, and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:220–9.

Wolf AM, Colditz GA. Current estimates of the economic cost of obesity in the United States. Obes Res. 1998;6:97–106.

Canadian Paediatric Society. Dieting in adolescence. Paediatr Child Health. 2004;9:487–503.

Davis C. Eating disorders and hyperactivity: A psychobiological perspective. Can J Psychol. 1997:168–175

Jacobi C, Hayward C, de Zwaan M, Kraemer HC, Agras SW. Coming to terms with risk factors for eating disorders: Application of risk terminology and suggestions for a general taxonomy. Psychol Bull. 2004;130:19–65.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Weight Losss Surgery in Australia. Canberra; 2010.

NHMRC. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Overweight and Obesity in Adults, Adolescents and Children in Australia. 2013.

Sjöström L, Lindroos A-K, Peltonen M, Torgerson J, Bouchard C, Carlsson B, Dahlgren S, Larsson B, Narbro K, Sjöström CD, Sullivan M, Wedel H. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2683–93.

Sjöström L, Narbro K, Sjöström CD, Karason K, Larsson B, Wedel H, Lystig T, Sullivan M, Bouchard C, Carlsson B, Bengtsson C, Dahlgren S, Gummesson A, Jacobson P, Karlsson J, Lindroos A-K, Lönroth H, Näslund I, Olbers T, Stenlöf K, Torgerson J, Agren G, Carlsson LMS. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:741–52.

Sarwer DB, Thompson JK, Mitchell JE, Rubin JP. Psychological considerations of the bariatric surgery patient undergoing body contouring surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:423e–34e.

Mitchell JE, Crosby R, de Zwaan M, Engel S, Roerig J, Steffen K, Gordon KH, Karr T, Lavender J, Wonderlich S. Possible risk factors for increased suicide following bariatric surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21:665–72.

Tindle HA, Omalu B, Courcoulas A, Marcus M, Hammers J, Kuller LH. Risk of suicide after long-term follow-up from bariatric surgery. Am J Med. 2010;123:1036–42.

Peterhansel C, Petroff D, Klinitzke G, Kersting A, Wagner B, Peterhänsel C, Petroff D, Klinitzke G, Kersting A, Wagner B. Risk of completed suicide after bariatric surgery: A systematic review. Obes Rev. 2013;14:369–82.

Vagenas K. Prospective evaluation of laparoscopic Roux en Y gastric bypass in patients with clinically severe obesity. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6024.

Abilés V, Rodríguez-Ruiz S, Abilés J, Mellado C, García A, Pérez De La Cruz A, Fernández-Santaella MC. Psychological characteristics of morbidly obese candidates for bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2010;20:161–7.

Higgs ML, Wade T, Cescato M, Atchison M, Slavotinek A, Higgins B. Differences between treatment seekers in an obese population: Medical intervention vs. dietary restriction. J Behav Med. 1997;20:391–406.

Murphy KD, Hayden MJ, Brown WA, O’Brien PE. Does binge eating disorder negatively impact weight loss after bariatric surgery? Obes Res Clin Pract. 2016;6:91.

Colles SL, Dixon JB, O’Brien PE. Grazing and loss of control related to eating: Two high-risk factors following bariatric surgery. Obesity. 2008;16:615–22.

Saunders R. Binge eating in gastric bypass patients before surgery. Obes Surg. 1999;9:72–6.

Dodsworth A, Warren-Forward H, Baines S. Changes in eating behavior after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: A systematic review of the literature. Obesity Surgery 2010:1579–1593

Livhits M, Mercado C, Yermilov I, Parikh JA, Dutson E, Mehran A, Ko CY, Gibbons MM. Preoperative predictors of weight loss following bariatric surgery: Systematic review. Obes Surg. 2012;22:70–89.

Niego SH, Kofman MD, Weiss JJ, Geliebter A. Binge eating in the bariatric surgery population: A review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:349–59.

Marino JM, Ertelt TW, Lancaster K, Steffen K, Peterson L, de Zwaan M, Mitchell JE. The emergence of eating pathology after bariatric surgery: A rare outcome with important clinical implications. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45:179–84.

Ashton K, Drerup M, Windover A, Heinberg L. Brief, four-session group CBT reduces binge eating behaviors among bariatric surgery candidates. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2009;5:257–62.

Kinzl JF. Morbid obesity: Significance of psychological treatment after bariatric surgery. Eat Weight Disord. 2010;15.

Saunders R. Post-surgery group therapy for gastric bypass patients. Obes Surg. 2004:1128–1131.

Atchison M, Wade T, Higgins B, Slavotinek T. Anorexia nervosa following gastric reduction surgery for morbid obesity. Int J Eat Disord. 1998;23:111–16.

de Zwaan M, Hilbert A, Swan-Kremeier L, Simonich H, Lancaster K, Howell LM, Monson T, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE. Comprehensive interview assessment of eating behavior 18–35 months after gastric bypass surgery for morbid obesity. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6:79–85.

Conceição E, Orcutt M, Mitchell J, Engel S, Lahaise K, Jorgensen M, Woodbury K, Hass N, Garcia L, Wonderlich SA. Eating disorders after bariatric surgery: A case series. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46:274–9.

Dixon JB, McPhail T, O’Brien PE. Minimal reporting requirements for weight loss: Current methods not ideal. In Obesity Surgery. 2005;15:1034–9.

Kim S, Popkin BM. Commentary: Understanding the epidemiology of overweight and obesity - a real global public health concern. Int J Epidemiol. 2006:60-7–2.

Burns M, Gavey N. “Healthy weight” at what cost? “Bulimia” and a discourse of weight control. J Health Psychol. 2004;9:549–65.

Bombak AE. Obesity, health at every size, and public health policy. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:60–8.

Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: What will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff Clin Pract. 1998:2–4.

Grima M, Dixon JB. Obesity-recommendations for management in general practice and beyond. Aust Fam Physician. 2013;42:532–41.