Abstract

Background

At present, the hereditary hearing loss homepage, (https://hereditaryhearingloss.org/), includes 258 deafness genes and more than 500 genes that have been reported to cause deafness. With few exceptions, the region-specific distributions are unclear for many of the identified variants and genes.

Methods

Here, we used a custom capture panel to perform targeted sequencing of 518 genes in a cohort of 879 deaf Chinese probands who lived in Yunnan. Mutation sites of the parents were performed by high-throughput sequencing and validated by Sanger sequencing.

Results

The ratio of male to female patients was close to 1:1 (441:438) and the age of onset was mainly under six. Most patients (93.5%) were diagnosed with moderate to severe deafness. Four hundred and twenty-eight patients had variants in a deafness gene, with a detection rate of 48.7%. Pathogenic variants were detected in 98 genes and a number of these were recurrent within the cohort. However, many of the variants were rarely observed in the cohort. In accordance with the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics, pathogenic, likely pathogenic and variants of uncertain significance accounted for 34.3%, 19.3% and 46.4% of all detected variants, respectively. The most common genes included GJB2, SLC26A4, MYO15A, MYO7A, TMC1, CDH23, USH2A and WFS1, which contained variants in more than ten cases. The two genes with the highest mutation frequency were GJB2 and SLC26A4, which accounted for 28.5% (122/428) of positive patients. We showed that more than 60.3% of coding variants were rare and novel. Of the variants that we detected, 80.0% were in coding regions, 17.9% were in introns and 2.1% were copy number variants.

Conclusion

The common mutation genes and loci detected in this study were different from those detected in other regions or ethnic groups, which suggested that genetic screening or testing programs for deafness should be formulated in accordance with the genetic characteristics of the region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hereditary hearing loss (HL) is one of the most common sensory disorders, with an incidence of 1–2 cases per 1000 newborns [1]. In 2021, the World Health Organization reported that more than 1.5 billion people experience some decline in their hearing capacity during their life course and at least 430 million will require care [2]. Hereditary hearing loss is nonsyndromic in 70% of newborns. The remaining 30% present with the syndromic form and exhibit additional abnormalities [3]. Deafness is a disease with high genetic and clinical heterogeneity. Clinical diagnosis can determine the degree of deafness but cannot clarify the cause of the disease. The molecular etiology of most patients can be identified by a combination of genetic testing and clinical diagnosis [3, 4]. The introduction of next-generation sequencing (NGS) has resulted in great progress in the diagnostics of HL [5, 6]. As of July 2022, mutations in 258 different genes have been reported to cause HL (http://hereditaryhearingloss.org). Genetic factors account for more than 50% of cases, in which the majority exhibit autosomal recessive inheritance (75–80%). Twenty to twenty-five percent show autosomal dominant inheritance and 1.0-1.5% show X-linked or mitochondrial inheritance [7].

To date, the genes involved and the spectrum of mutations are largely unknown in early HL patients from Yunnan. In this study, we presented the results of an NGS analysis of a large cohort of 879 patients with deafness. Using this large number of patients, we expected to reveal the genes and variants that cause HL in the Yunnan region.

Materials and methods

Subjects

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kunming Children's Hospital (Kunming, China). Informed consent was obtained from the parents of the patients, prior to sampling. The diagnosis of HL was established via standard audiometry, in a soundproofed room, in accordance with the current clinical standards. Hearing loss was classed as either congenital onset or prelingual onset and the severity was established as mild (between 25 and 40 dB), moderate (between 40 and 70 dB) or severe/profound (> 70 dB). Clinical evaluation included a thorough physical examination and otoscopy, in all cases. Additional evaluations, which included a high-resolution, thin-section computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the temporal bone, were performed when possible. We extracted DNA from peripheral blood leukocytes of the probands, in accordance with standard procedures.

DNA extraction, library construct, sequencing and quality control

EDTA anti-coagulated venous blood (3 ml) were collected from a cohort of 879 deaf Chinese probands and the parents of 357 patients. The genomic DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit following the manufacturer’s protocol. Then make the DNA fragmentaion after quality control. DNA sequencing library was constructed by NEXTflex Rapid DNA-Seq Kit and Deaf-gene Panel probes were used for library capture. Samples were analyzed using a 518 gene panel (Additional file 1: Table S1), on the Illumina Next Generation Sequencing platform. The 518 gene panel was a probe capture panel that was comprised of non-syndromic deafness genes (such as GJB2 and GJB3), syndromic deafness genes (such as SLC26A4, FOXI1 and EDN3) and mitochondrial deafness genes (such as MT-TS1, MT-RNR1, MT-TL1, MT-TK and MT-TE).The prepared library was loaded onto NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina, CA, United States). The average coverage was ≥ 100, the percentage of target region ≥ 20 × was ≥ 98%, and, and Q20 ≥ 95% were set as the sequencing quality parameters.

Bioinformation analysis

The sequenced reads were aligned to the reference genome (hg19) using BWA MEN, and PCR duplicates were marked with PICARD. Variants were called by HaplotypeCaller in GATK4.0 with default parameters, and retained considering DP (reads depth) ≥ 10, MQ (Mapping Quality) ≥ 30 and GQ(Genotyping Quality) ≥ 20. After annotation using ANNOVAR, variants both in coding region and splicing site were kept and synonymous variants were removed.

Variant curation

Deafness-Associated Genes Panel can obtain about 5 thousand variants in one patient and most of the variants are benign. Those variants can be screened through database of normal crowd (gnomAD, threshold is set as 0.1%) and Computational (in silico) predictive (Revel). About 100 are selected. And then screened by variant types, genetic mode, HGMD and ClinVar database to confirm several target variants. And the target variants are curationed according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) [8] and the Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP) guidelines, the ClinGen SVI general recommendations and the ClinGen VCEP recommendations. Using the following evidence: (1) the frequency in the normal population (gnomAD database); (2) computational prediction: mutations were predicted using Pubvar (https://www.pubvar.com/), with several prediction software packages, such as Polyphen, SIFT and MutationTaster; (3) literature reports: target variants were searched in HGMD, ClinVar and Pubmed. The variants are classified into Pathogenic (P), Likely Pathogenic (LP), Benign (B), Likely Benign (LB), and Uncertain significance (VUS).

Sanger sequencing

The target variants were validated by Sanger sequencing. Sequencing primers were designed using online Primer Designer Tool and compared with those from public databases to avoid SNPs and nonspecific amplification. Genomic DNA was amplified using the HotStarTaq Master Mix Kit with the following conditions: 95 °C for 15 min; followed by a program of 94 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 45 s for 35 cycles; and ending with a 10-min extension at 72 °C. Amplication program was different according to different target DNA sequence. Amplicons were purified using ExoSAP-IT Express and bidirectionally sequenced using BigDye Terminator version 1.1 on an ABI3730xl DNA analyzer. Data analysis was conducted using Applied Biosystems Minor Variant Finder.

Results

Patients

We sequentially accrued 879 HL patients during the study period. There were no exclusion criteria. As shown in Table 1, the demographics of the patients were binned into five categories: Sex, onset, severity, family history and physical exam. There were 72 patients who did not provide clinical information. The ratio of male to female patients was close to 1:1 (441:438) and the largest group for the age of onset data was ‘under the age of six’. The most common characteristics included: young age (86.2% were < 18 years of age) and severe-to-profound HL (44.5%). Most patients had a normal physical exam (81.8%) and approximately one-third had no family history of HL (37.3%).

Molecular findings among probands

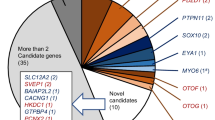

As shown in Fig. 1, 428 out of the 879 (48.7%) patients had mutations (Additional file 2: Table S2) in known HL genes, which were classified as pathogenic (P), likely pathogenic (LP) or variants of uncertain significance (VUS), in accordance with ACMG. The basic and diagnostic information for each sample were shown in Fig. 2. The GJB2 and SLC26A4 genes were the most common deafness susceptibility genes and their mutations accounted for 28.5% [GJB2: 16.6% (71/428), SLC26A4: 11.9% (51/428)] of mutation positive patients in our study. Three hundred and six patients (71.5%) had others known deafness gene variants. The molecular etiology of the remaining 450 patients was not identified. In our analysis of the detected genetic variants, we have used a healthy control group from the Chinese population that included WES data from 5000 normal people provided by MyGenostics Inc (Inhouse). All the mutation sites in this study have relatively low carry rates in the normal population (except GJB2 and SLC26A4, Additional file 3: Table S3), and approximately 36.4% of the VUS variants in this study had zero carry rates in healthy controls (Additional file 3: Table S3).

The interaction graph of basic and diagnostic information for each sample. Positive diagnosis is influenced by ethnic, clinical, and phenotypic characteristics in sporadic hearing loss population. N for each combination of two reported characteristics for all combinations. Color/shading reflects the number of patients with the paired criteria, up to the maximum of n = 822. AD autosomal dominant, AR autosomal recessive

Using the pedigree analysis and NGS results, we observed autosomal dominant inheritance for 160 of the 428 deafness gene variants (160/428, 37.4%) and autosomal recessive inheritance for 260 variants (260/428, 60.7%). We observed X-linked inheritance in 10 cases (10/428, 2.3%) and mitochondrial gene mutation in two cases (2/428, 0.5%). In this cohort, sequence variants were identified in a total of 98 genes (Table 2). The genes that were identified in at least five patients included GJB2 (16.6%; 71/428), SLC26A4 (11.9%; 51/428), MYO15A (5.1%; 22/428), MYO7A (4.9%; 21/428), TMC1 (3.7%; 16/428), CDH23 (3.3%; 14/428), MITF (3.0%; 13/428), USH2A (3.0%; 13/428), WFS1 (2.6%; 11/428), COL11A2 (2.3%; 10/428), OTOF (2.3%; 10/428), SOX10 (2.3%; 10/428), PTPN11 (1.9%; 8/428), OTOG (1.4%; 6/428), TNC (1.4% 6/428), EYA1 (1.2%; 5/428), GJB3 (1.2%; 5/428) and TECTA (1.2%; 5/428).

Analysis of NGS data indicated that 428 patients had variants that could be classified as P, LP or VUS, based on ACMG guidelines. These accounted for 34.3%, 19.3% and 46.4% of variants, respectively. Of the 428 variants, 42.3% had previously been reported in the literature, whilst 57.7% were novel. Variants that led to protein truncation, such as frameshift mutations and nonsense mutations, were found at a higher rate and were usually classed as P or LP (Fig. 3). In addition, missense mutations or splice mutations were also detect in large numbers and rated as P or LP. It was noted that a small number of copy number variations (CNVs) were detected among the pathogenic variants. However, the proportion of mutation types in the VUS class was quite different from that of the P and LP classes. Missense mutations were the most common mutation type in the VUS class and most had not been included in the database or previously reported in the literature.

Using the mutation types found in more than five probands in this deafness cohort, it was observed that the proportion of missense mutations was the highest, followed by frameshift mutations and splicing mutations (Fig. 4). We also noted a wide variation across genes in the fractional contribution of missense versus loss of function (LOF) variants (frameshift and nonsense) (Fig. 4). Some genes had exclusively missense mutations (WFS1 and TECTA, Fig. 4).

The proportion of CNVs was 2.1% (Fig. 4). Six compound heterozygous CNVs were identified in SLC26A4 and two heterozygous CNVs were identified in EYA1 and MITF. One novel, homozygous CNV, which was a deletion that spanned exons 37–50 of the CDH23 gene, was identified in this cohort. Deleted exons did not amplify in confirmatory PCR reactions from proband samples.

Discussion

The development of the Human Genome Project has promoted the combination of genetics and clinical medicine for diagnostics. The emergence of genetic screening and diagnosis for deafness is of great significance for the clarification of the cause of deafness and to prevent its occurrence [9,10,11]. Since the 1980s, with the development of technology, great progress has been made in the study of the genetic etiology of deafness. To date, more than 258 deafness genes have been cloned or identified (https://hereditaryhearingloss.org/) and it has been reported that more than 500 genes may contribute to the deafness phenotype. However, the diagnosis of hereditary deafness is extremely challenging for the following reasons: Firstly, hereditary deafness is a disease with very high genetic, clinical and ethnic heterogeneity. Secondly, hereditary deafness genes may have different categories of genetic variants, such as single nucleotide variations (SNVs), insertions and deletions (INDELs) and CNVs. Thirdly, most deafness gene variants do not occur repeatedly.

The introduction of NGS into the field of medical genetics has opened up new horizons for clinical diagnosis and scientific research and it has become a powerful auxiliary technology. Over the past decade, studies have attempted to enrich the known HL genes using capture-based or PCR-based targeted enrichment methods, followed by NGS, to screen for variants [12]. It can be concluded that the sensitivity and specificity of NGS for HL genetic detection is comparable to conventional Sanger sequencing, based on previous studies. Recently, Gema García-García et al. [13] detected the variants responsible for the disease in 47 out of 118 families (40%), with a custom panel that included 59 genes associated with non-syndromic or syndromic HL. Seco et al. [14] published a study that evaluated the diagnostic utility of NGS targeting using a gene panel of 120 HL-related genes. Using this strategy, they were able to identify a causative variant of HL in 67 out of 200 patients (33.5%). In this study, 518 deafness-related genes were identified in 879 patients. Deafness gene variants were detected in 428 children and the detection rate was 48.7%, which was slightly higher than the detection rates observed when using the smaller gene panels that contain the common deafness-related variants. Our study showed that the more deafness-related genes that are included, the higher the detection rate, which indicates that some populations have rare variants. These results are significant for the molecular diagnosis of deafness and further research.

With the continuous development of gene sequencing technology, the ability of variation detection far exceeds the ability of clinical interpretation, more and more VUS variants have been detected and reported [15,16,17]. In this study, 46.4% of those detected mutation sites were rated as VUS, which accounted for almost half of the total mutations. However, the majority of gene variants assessed as VUS are very rare, with low detection rate in human, making it difficult to interpret such variants. In this study, about 90% of the VUS variants are missense mutations, which may often be considered to causes a slight impact because they only cause one amino acid change. In fact, missense mutations may be the main types of mutations in some genes. According to the HGMD database, about 89.0% of the variants in CDH23 gene, 85.0% of the variants in TECTA gene, and 69.4% of the variants in OTOF gene are missense mutations, which reminds us that the missense mutations in deafness causative genes should be given more consideration. With the deepening of research and the accumulation of deafness sequencing data, some databases have been established, such as the Deafness Variation Database (DVD) [17], which can re-adjust the ACMG ranking of variants. The clinical diagnostic value of VUS may be considered by intergrating the ranking results of different databases. In addition, McDiarmid [18] used CRISPR-Cas9 genome engineering technique to modify model organisms to study the association of VUS with disease. Therefore, some variants are classified as VUS may only be temporary for now. With the decrease of sequencing cost, more and more sequencing results of deaf people or even normal people will be studied. The accumulation of sequencing data will help more accurate analysis and ranking of variations, which are why we include VUS variables into this study. What needs to be emphasized here is that although we report these VUS mutations, the pathogenicity is still unclear. The clinical reference to these variants in the diagnosis of deafness requires great caution.

Deafness is a disease with high genetic heterogeneity and one of the manifestations is that the high-frequency mutation genes are different in different populations. The GJB2 and MYO6 genes are the most commonly mutated HL genes in the global population [1, 19]. In Czech patients, the common HL genes are GJB2 and STRC [20, 21]. However, in the Chinese population, the common HL genes are GJB2 and SLC26A4 [9]. These studies show that molecular diagnostic analyses are highly population dependent, as the mutation spectrum for HL can differ greatly between populations. In this study, variants were detected in ten genes (GJB2, SLC26A4, MYO15A, MYO7A, TMC1, CDH23, MITF, USH2A, WFS1 and SOX10), which explained 55.7% of patients with deafness variants. With the exception of mutations in two relatively common genes, GJB2 (16.6%) and SLC26A4 (11.9%), most reported mutations were present in only a single or a small number of families. After excluding GJB2 and SLC26A4 mutations, we detected P, LP or VUS mutations in the known HL genes in 34.9% of the probands.

Our results demonstrated that NGS screening is a powerful technology for the identification of mutations in HL genes. From an epidemiological perspective, GJB2 and SLC26A4 mutations were involved in 28.5% of cases of deafness with a gene variant, while the remaining cases arose from rare gene mutations. For instance, CDH23, PCDH15 and MYO7A are large genes and it appears that these genes are more prone to mutations [22, 23]. The mutations in some genes did not appear repeatedly. For example, none of the mutations in the SOX10 and MITF genes were recurrent in our cohort. This may indicate that SOX10 and MITF are relatively more prone to de novo mutations or that they are highly conserved genes in which variation is rarely tolerated. Some genes, such as TNIE and TPRN, had less than 20 loci reported in the HGMD database. In these two genes, only one case of a rare gene mutation was detected in our cohort. In contrast, four patients in our study had BDP1 gene mutations, despite this gene having less than 20 mutation sites in the HGMG database. It is worth noting that, among these four individuals, three had the same mutation, which has not been reported in the literature. This suggested that this locus may be a funder mutation, as they are all from Zhaotong city of Yunnan Province in southwest China.

Mutations in introns may be relatively common in deafness patients. Among the 98 deafness-related genes detected in this study, SLC26A4 (62.7%, 32/51), MYO15A (63.6%, 14/22), OTOF (40.0%, 4/10) and PTPRQ (75.0%, 3/4) contained intronic variants. In previous studies, it has been confirmed that the intron of SLC26A4 is prone to mutations, especially at the c.919-2A > G site, which is one of the mutation hotspots in the Asian population [24, 25]. Our research also confirmed this. The variants detected in this study included common intronic mutations and also some rare or novel variants. This suggested that there are some unknown variant sites that require comprehensive testing, in order to find more genetic variants.

Copy number variants are a major contributor to hereditary HL, which shows the importance of the inclusion of CNV detection in a molecular diagnostic analysis for HL [26, 27]. Although there have been studies that show the importance of CNV analysis of NGS data, in the etiology of deafness, this analysis method is still being optimized for clinical use. The study by Shearer et al. [28] used targeted enrichment and NGS with integrated CNV detection for HL in 686 patients. At least one CNV within a known deafness gene was observed in 15.2% (104) of patients. In our cohort, we used NGS to identify CNVs in four different genes (SLC26A4, MITF, EYA1 and CDH23), in nine patients (2.1%, 9/428). Several studies have shown that STRC and OTOA are two of the deafness genes that are more prone to CNVs [28,29,30]. However, we only detected a heterozygous deletion in exons 2–9 of the STRC gene in one patient. Because the variant is not autosomal recessive, this patient is a carrier. Therefore, it was not included in the positive results of this study. We did not detect CNV in the OTOA gene, which may be caused by regional differences. These results demonstrated that NGS can detect CNVs but more medical records and studies are needed to confirm whether all CNVs can be detected [31].

This study was not able to fully identify and explain the molecular etiology of all patients. Deafness-related gene variants were not detected in 20.8% of the 879 patients. These patients were likely to have undetected variants but more research is needed to confirm this speculation. It was noted that 43.2% of the unsolved patients had a pathogenic variant in a known HL gene. These patients may have had another mutation that had not been detected, or they may have been carriers who had developed deafness [32, 33]. Deafness can also occur through an oligogenic pattern of inheritance, were two or more pathogenic variants in different genes are detected in individuals with unsolved HL. Combinations of some variants have been reported to be the cause of oligogenesis, such as variants in SLC26A4 and KCNJ10, or SLC26A4 and FOXI1 [34]. However, we did not find any patients with the previously reported combinations of variants.

In this study, we applied NGS technology to (1) identify the molecular epidemiological etiology of HL in Chinese children and (2) discover novel mutations in causative genes. The results of the study provide a reference for the development of genetic screening or diagnosis of deafness, which is suitable for this region. In our analysis, we only considered coding regions, which is a limitation of this study. Pathogenic variants in noncoding regions or transcripts may also cause HL. In addition, due to the lack of family history, it was not clear whether the deafness gene variants carried by some patients contributed to the development of the disease.

Our data indicated that many rare variants are responsible for HL in this cohort and these mutations can be detected using NGS, which is approximately comparable in accuracy to Sanger sequencing. It is likely that there are undetected, rare variants that are specific to the Chinese population. Therefore, the main challenge for the future will be the establishment of population specific mutation-spectra, to achieve accurate, personalized, comprehensive molecular testing for HL.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- HL:

-

Hereditary hearing loss

- NGS:

-

Next-generation sequencing

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- ACMG:

-

American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics

- P:

-

Pathogenic

- LP:

-

Likely pathogenic

- VUS:

-

Variants of uncertain significance

- CNVs:

-

Copy number variations

- LOF:

-

Loss of function

- SNVs:

-

Nucleotide variations

- INDELs:

-

Insertions and deletions

References

Kenneson A, Van Naarden BK, Boyle C. GJB2 (connexin 26) variants and nonsyndromic sensorineural hearing loss: a HuGE review. Genet Med. 2002;4:258–74.

World Report on Hearing. World Health Organization (2021).

Sloan-Heggen CM, Bierer AO, Shearer AE, Kolbe DL, Nishimura CJ, Frees KL, Ephraim SS, Shibata SB, Booth KT, Campbell CA, Ranum PT, Weaver AE, Black-Ziegelbein EA, Wang D, Azaiez H, Smith R. Comprehensive genetic testing in the clinical evaluation of 1119 patients with hearing loss. Hum Genet. 2016;135:441–50.

Xiang J, Jin Y, Song N, Chen S, Shen J, Xie W, Sun X, Peng Z, Sun Y. Comprehensive genetic testing improves the clinical diagnosis and medical management of pediatric patients with isolated hearing loss. BMC Med Genom. 2022;15:142.

Vona B, Muller T, Nanda I, Neuner C, Hofrichter MA, Schroder J, Bartsch O, Lassig A, Keilmann A, Schraven S, Kraus F, Shehata-Dieler W, Haaf T. Targeted next-generation sequencing of deafness genes in hearing-impaired individuals uncovers informative mutations. Genet Med. 2014;16:945–53.

Mutai H, Suzuki N, Shimizu A, Torii C, Namba K, Morimoto N, Kudoh J, Kaga K, Kosaki K, Matsunaga T. Diverse spectrum of rare deafness genes underlies early-childhood hearing loss in Japanese patients: a cross-sectional, multi-center next-generation sequencing study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:172.

Sommen M, Wuyts W, Van Camp G. Molecular diagnostics for hereditary hearing loss in children. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2017;17:751–60.

Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, Voelkerding K, Rehm HL. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–24.

Dai P, Huang LH, Wang GJ, Gao X, Qu CY, Chen XW, Ma FR, Zhang J, Xing WL, Xi SY, Ma BR, Pan Y, Cheng XH, Duan H, Yuan YY, Zhao LP, Chang L, Gao RZ, Liu HH, Zhang W, Huang SS, Kang DY, Liang W, Zhang K, Jiang H, Guo YL, Zhou Y, Zhang WX, Lyu F, Jin YN, Zhou Z, Lu HL, Zhang X, Liu P, Ke J, Hao JS, Huang HM, Jiang D, Ni X, Long M, Zhang L, Qiao J, Morton CC, Liu XZ, Cheng J, Han DM. Concurrent hearing and genetic screening of 180,469 neonates with follow-up in Beijing, China. Am J Hum Genet. 2019;105:803–12.

Kim BJ, Oh DY, Han JH, Oh J, Kim MY, Park HR, Seok J, Cho SD, Lee SY, Kim Y, Carandang M, Kwon IS, Lee S, Jang JH, Choung YH, Lee S, Lee H, Hwang SM, Choi BY. Significant Mendelian genetic contribution to pediatric mild-to-moderate hearing loss and its comprehensive diagnostic approach. Genet Med. 2020;22:1119–28.

Le Nabec A, Collobert M, Le Marechal C, Marianowski R, Ferec C, Moisan S. Whole-genome sequencing improves the diagnosis of DFNB1 monoallelic patients. Genes (Basel). 2021;12:1267.

Shearer AE, Smith RJ. Massively parallel sequencing for genetic diagnosis of hearing loss: the new standard of care. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;153:175–82.

Garcia-Garcia G, Berzal-Serrano A, Garcia-Diaz P, Villanova-Aparisi R, Juarez-Rodriguez S, de Paula-Vernetta C, Cavalle-Garrido L, Jaijo T, Armengot-Carceller M, Millan JM, Aller E. Improving the management of patients with hearing loss by the implementation of an NGS panel in clinical practice. Genes (Basel). 2020;11:1467.

Zazo SC, Wesdorp M, Feenstra I, Pfundt R, Hehir-Kwa JY, Lelieveld SH, Castelein S, Gilissen C, de Wijs IJ, Admiraal RJ, Pennings RJ, Kunst HP, van de Kamp JM, Tamminga S, Houweling AC, Plomp AS, Maas SM, de Koning GP, Kant SG, de Geus CM, Frints SG, Vanhoutte EK, van Dooren MF, van den Boogaard MH, Scheffer H, Nelen M, Kremer H, Hoefsloot L, Schraders M, Yntema HG. The diagnostic yield of whole-exome sequencing targeting a gene panel for hearing impairment in The Netherlands. Eur J Hum Genet. 2017;25:308–14.

Yu F, Han DY, Dai P, Kang DY, Zhang X, Liu X, Zhu QW, Yuan YY, Sun Q, Xue DD, Li M, Liu J, Yuan HJ, Yang WY. Mutation of GJB2 gene in nonsyndromic hearing impairment patients: analysis of 1190 cases. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2007;87:2814–9.

Jin X, Huang S, An L, Zhang C, Dai P, Gao H, Ma X. Variant analysis of 92 Chinese Han families with hearing loss. BMC Med Genom. 2022;15:12.

Azaiez H, Booth KT, Ephraim SS, Crone B, Black-Ziegelbein EA, Marini RJ, Shearer AE, Sloan-Heggen CM, Kolbe D, Casavant T, Schnieders MJ, Nishimura C, Braun T, Smith R. Genomic landscape and mutational signatures of deafness-associated genes. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;103:484–97.

McDiarmid TA, Au V, Loewen AD, Liang J, Mizumoto K, Moerman DG, Rankin CH. CRISPR-Cas9 human gene replacement and phenomic characterization in Caenorhabditis elegans to understand the functional conservation of human genes and decipher variants of uncertain significance. Dis Model Mech. 2018;11:dmm036517.

Del CI, Morin M, Dominguez-Ruiz M, Moreno-Pelayo MA. Genetic etiology of non-syndromic hearing loss in Europe. Hum Genet. 2022;141:683–96.

Seeman P, Malikova M, Raskova D, Bendova O, Groh D, Kubalkova M, Sakmaryova I, Seemanova E, Kabelka Z. Spectrum and frequencies of mutations in the GJB2 (Cx26) gene among 156 Czech patients with pre-lingual deafness. Clin Genet. 2004;66:152–7.

Safka BD, Poisson MS, Meszarosova AU, Jencik J, Cejnova V, Cada Z, Lastuvkova J, Raskova D, Seeman P. Spectrum and frequencies of non GJB2 gene mutations in Czech patients with early non-syndromic hearing loss detected by gene panel NGS and whole-exome sequencing. Clin Genet. 2020;98:548–54.

Tekin D, Yan D, Bademci G, Feng Y, Guo S, Foster JN, Blanton S, Tekin M, Liu X. A next-generation sequencing gene panel (MiamiOtoGenes) for comprehensive analysis of deafness genes. Hear Res. 2016;333:179–84.

Tropitzsch A, Schade-Mann T, Gamerdinger P, Dofek S, Schulte B, Schulze M, Battke F, Fehr S, Biskup S, Heyd A, Muller M, Lowenheim H, Vona B, Holderried M. Diagnostic yield of targeted hearing loss gene panel sequencing in a large German cohort with a balanced age distribution from a single diagnostic center: an eight-year study. Ear Hear. 2022;43:1049–66.

Cheng YF, Chan YH, Hu CJ, Lu YC, Saeki T, Hosoya M, Saegusa C, Fujioka M, Okano H, Weng SM, Hsu CJ, Chang KH, Wu CC. Generation of a human iPS cell line (CGMH.SLC26A4919–2) from a Pendred syndrome patient carrying SLC26A4 c.919–2A>G splice-site mutation. Stem Cell Res. 2019;40:1524.

Dai P, Li Q, Huang D, Yuan Y, Kang D, Miller DT, Shao H, Zhu Q, He J, Yu F, Liu X, Han B, Yuan H, Platt OS, Han D, Wu BL. SLC26A4 c.919–2A>G varies among Chinese ethnic groups as a cause of hearing loss. Genet Med. 2008;10:586–92.

Haraksingh RR, Jahanbani F, Rodriguez-Paris J, Gelernter J, Nadeau KC, Oghalai JS, Schrijver I, Snyder MP. Exome sequencing and genome-wide copy number variant mapping reveal novel associations with sensorineural hereditary hearing loss. BMC Genom. 2014;15:1155.

Abbasi W, French CE, Rockowitz S, Kenna MA, Eliot SA. Evaluation of copy number variants for genetic hearing loss: a review of current approaches and recent findings. Hum Genet. 2022;141:387–400.

Shearer AE, Kolbe DL, Azaiez H, Sloan CM, Frees KL, Weaver AE, Clark ET, Nishimura CJ, Black-Ziegelbein EA, Smith RJ. Copy number variants are a common cause of non-syndromic hearing loss. Genome Med. 2014;6:37.

Yokota Y, Moteki H, Nishio SY, Yamaguchi T, Wakui K, Kobayashi Y, Ohyama K, Miyazaki H, Matsuoka R, Abe S, Kumakawa K, Takahashi M, Sakaguchi H, Uehara N, Ishino T, Kosho T, Fukushima Y, Usami SI. Frequency and clinical features of hearing loss caused by STRC deletions. Sci Rep. 2019;9:4408.

Knijnenburg J, Oberstein SAJL, Frei K, Lucas T, Gijsbers ACJ, Ruivenkamp CAL, Tanke HJ, Szuhai K. A homozygous deletion of a normal variation locus in a patient with hearing loss from non-consanguineous parents. J Med Genet. 2009;46:412–7.

Rajagopalan R, Murrell JR, Luo M, Conlin LK. A highly sensitive and specific workflow for detecting rare copy-number variants from exome sequencing data. Genome Med. 2020;12:14.

Safka BD, Uhrova MA, Lassuthova P, Varga L, Stanek D, Borecka S, Lastuvkova J, Cejnova V, Raskova D, Lhota F, Gasperikova D, Seeman P. The cause of hereditary hearing loss in GJB2 heterozygotes-a comprehensive study of the GJB2/DFNB1 region. Genes (Basel). 2021;12:684.

Chen K, Wang X, Sun L, Jiang H. Screening of SLC26A4, FOXI1, KCNJ10, and GJB2 in bilateral deafness patients with inner ear malformation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;146:972–8.

Yang T, Gurrola JN, Wu H, Chiu SM, Wangemann P, Snyder PM, Smith RJ. Mutations of KCNJ10 together with mutations of SLC26A4 cause digenic nonsyndromic hearing loss associated with enlarged vestibular aqueduct syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:651–7.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to MyGenostics Inc for provided the NGS sequencing data of 5000 healthy control subjects from China.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Fund of China (Grant No. 82060192), Reserve Talents for Young and Middle‐aged Academic and Technical Leaders in Yunnan Province (Grant No. 2019HB102), Academician (Expert) Workstation in Yunnan Province (Grant No. 202105AF150056), Yunnan Applied Basic Research-Joint Special Project of Kunming Medical University (Grant No. 202001AY070001-170).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JM, XLM and KL designed the study, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. RH, XYB, CM and LL designed the study, collected data and wrote the manuscript. XYB, LPZ and QDC performed the literature review and revised the manuscript. XL, GL and LPZ confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. TY, YQG and TSZ conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The presented study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by The Ethics Committee of Kunming Children’s Hospital (Kunming, China, Grant No. 2020-01-009-H01). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

The panel containing 518 genes associated with deafness.

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Mutations identified in known hearing loss genes.

Additional file 3: Table S3.

The frequency of mutation site in 5000 normal population.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, J., Ma, X., Lin, K. et al. Genetic screening of a Chinese cohort of children with hearing loss using a next-generation sequencing panel. Hum Genomics 17, 1 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40246-022-00449-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40246-022-00449-1