Abstract

Background

In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), malnutrition coupled with rising rates of undernutrition and the burden of overweight/obesity remains one of the most significant public health challenges facing the region. Nutrition-sensitive agriculture can play an important role in reducing malnutrition by addressing the underlying causes of nutrition outcomes. Therefore, we aim to assess the nutrition-sensitivity of food and agriculture policies in SSA and to provide recommendations for identified policy challenges in implementing nutrition-sensitive agriculture initiatives.

Methods

We assessed past and current national policies relevant to agriculture and nutrition from Ethiopia, Ghana, Malawi, Nigeria, and South Africa. Thirty policies and strategies were identified and reviewed after a literature scan that included journal articles, reports, and policy documents on food and agriculture. The policies and strategies were reviewed against FAO’s Key Recommendations for Improving Nutrition Through Agriculture and Food Systems guidelines.

Results

Through the review of 30 policy documents, we found that the link between agriculture and nutrition remains weak, particularly in agriculture policies. The review of the policies highlighted insufficient attention to nutrition and the production of micronutrient-rich foods, lack of strategies to increase farmer market access, and weak multi-sectoral collaboration and capacity building.

Conclusion

Nutrition-sensitive agriculture has received scant attention in previous agricultural and food policies in SSA that were riddled with implementation issues, lack of capacity, and ineffective methods for multi-sector collaboration. Recognition of these challenges are leading countries to revise and create new policies that prioritize nutrition-sensitive agriculture as a key driver in overcoming malnutrition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

About 224 million of the 673 million of those undernourished reside in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), comprising about one-third of the global total [1]. According to FAO [2], an estimated 239 million people in SSA were malnourished at a prevalence rate of 22.8%. Simultaneously, malnutrition in the form of overnutrition is also on the rise in the region, with 9.2% of the adult population being obese (Table 1). The number of overweight children in SSA increased from 6.6 million to 9.7 million [3]. Obesity among adolescence doubled to 2.1% in boys and 3.5% in girls and overweight/obesity among adults increased from 28% in 2000 to 42% in 2016 [4]. Several factors such as food insecurity, shift to Western diets, infectious diseases, prolonged drought, floods, resource conflict are partly responsible for the double burden of undernutrition and obesity [2, 5, 6]. The nutrition transition which refers to the shifts in dietary patterns and physical activity that are associated with changes in economic and social development are also attributed to the rise of obesity [7,8,9].

Food policy addresses the food system of a country which encompasses a wide range of topics including food production, processing, distribution, consumption, and demand; structural influences of the food supply; food production and consumption in light of health and environment [10]. It also involves implementing research on food quality; establishing governance and lobbies that control food policies, and assessing the impact of the food system on society [11]. On the other hand, agriculture policies include policy instruments related to the domestic farm sector, trade, food pricing, and ensuring food safety [12]. Food and agriculture policies have the potential to influence dietary behaviors through factors such as food prices, transportation, pricing, etc. [13]. Specifically, food and agriculture policies are important in shaping optimal nutrition outcomes and local food environments by manipulating various elements of the food system including market and trade systems, consumer purchasing power, agricultural production, and food transformation and consumer demand [14, 15]. In SSA, the impact of food and agriculture policies on nutrition outcomes is exemplified through continued focus of policies on the production of staple crops such as maize which has limiting effects on improving diet-related chronic diseases [16, 17]. This calls for increased attention to promoting nutritionally rich foods and dietary diversity in food and agriculture policies, however approaches to achieve this are complex [18].

The impacts of agriculture on health and nutrition vary by regions and countries and can include improvements to food availability and access, food security, dietary quality and diversity, income, and women’s empowerment [19,20,21]. Nutrition-sensitive agriculture is a food-based approach to agricultural development that emphasizes nutritionally rich foods, dietary diversity, and food fortification in overcoming nutrition-related diseases. Interest in nutrition-sensitive agriculture over the past decade has resulted in the development of several conceptual frameworks [22,23,24,25,26,27]. A framework that emerged from the Tackling the Agriculture–Nutrition Disconnect in India (TANDI) initiative identifies pathways linking agriculture and nutrition [24]. The pathway describes agriculture as a source of food, agriculture as a source of income for food expenditure, agriculture policy and the effects of agriculture production on food prices, agriculture as a source of income for nonfood expenditure (i.e., healthcare), effects of women’s employment in agriculture on household decision-making, childcare practices and own nutritional and health status [24]. In addition to these frameworks, several nutrition-sensitive agriculture interventions have been implemented in SSA with varying levels of success. For example, biofortification programs in Mozambique of orange sweet potatoes was found to be successful in increasing the effects vitamin A intake among children [28]. In addition, evidence of a nutrition and gender sensitive agriculture intervention in Zambia which focused on homestead food production of nutrient-rich food had positive effects on some aspects of agricultural diversity and women’s empowerment (i.e., social capital, increased financial and agricultural decision-making power) [29]. However, the intervention had limited effects on child and household dietary diversity.

Due to the complex nature of the nutrition transition, harnessing the potential of existing and new agriculture and food policies can be critical in staving off the nutrition transition problem. Agriculture and food policies developed and implemented within an enabling environment and that contain explicit nutrition goals, prioritize the production and marketing of nutritious foods, and emphasize multi-sectoral collaboration can have far-reaching effects on malnutrition. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to review national food and agriculture policies and strategies of Ethiopia, Ghana, Malawi, Nigeria, and South Africa to determine if the policies and strategies are nutrition-sensitive. The review will shed light on policy challenges and will provide recommendations for countries to implement effective nutrition-sensitive agriculture initiatives. The current review will expand on the findings of similar studies [15, 30, 31] by reviewing past and more recently developed food and agriculture policies that were not included in the previous studies.

Methods

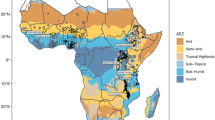

Through a case-study approach, we assessed past and current national policies relevant to agriculture and nutrition in Ethiopia, Ghana, Malawi, Nigeria, and South Africa to understand the challenges and opportunities in improving nutrition outcomes through food and agricultural policies. These countries were selected as they have a relatively high GDP, the variety of SSA regions they represent, have stable governance situations, their relatively larger populations sizes (such as Ethiopia and Nigeria), and the experience of the authors in these countries. A review of the literature was conducted that included journal articles, reports, and policy documents related to agriculture and nutrition. Specifically, national food and agriculture policies and strategies were searched for using the following online resources: websites of national ministries of health, food and/or agriculture, Google Scholar, and WHO Global Database on the Implementation of Nutrition Action. The keywords that were used in the search included food, nutrition, agriculture and national strategy or policy as well as the country names. A total of 30 policies and strategies were identified (7 from Nigeria, 7 from Ethiopia, 6 from South Africa, 6 from Malawi, and 4 from Ghana). Policies and strategies available from 1980 and onwards were included. An additional file presents a historical overview of national policies related to agriculture and nutrition in SSA (see Additional file 1). The nutrition-sensitivity of the policies and strategies were evaluated against the Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) 10 Key Recommendations for Improving Nutrition Through Agriculture and Food Systems [32]. The 10 key recommendations include: (1) incorporate explicit nutrition objectives and indicators; (2) assess the context; (3) target the vulnerable and improve equity; (4) collaborate and coordinate with other sectors; (5) maintain or improve the natural resource base; (6) empower women; (7) facilitate product diversification; (8) improve processing, storage and preservation; (9) expand markets and market access; and (10) incorporate nutrition promotion and education. Each policy/strategy was qualitatively reviewed to determine if there was explicit mention of goals/objectives/activities related to the FAO key recommendations.

Results

Review of national food and agriculture policies in sub-Saharan Africa

Ethiopia

Ethiopia began transforming the agricultural sector in the mid-1990s after creating a development strategy focusing on agriculture and national food security called the Agricultural Development-Led Industrialization (ADLI) (Table 2). Food insecurity was prevalent during this time due to the occurrence of several large scale famines and droughts which affected the nutritional status particularly among vulnerable populations, in which 41.9% of children were underweight in 1992 [33]. During this time policies were drawn from the Green Revolution in Asia which promoted agricultural intensification and commercialization to address decreasing food production and growing food insecurity [34, 35]. Although the large focus of the ALDI was on increasing food self-sufficiency as a strategy to achieving food security, the policy contained nutrition-sensitive aims related to the promotion of product diversification among smallholder farmers. The development of the ADLI was followed by the release of The Food Security Strategy of 1996 and the Food Security Program (FSP). The latter program also focused on crop diversification and improved farmer integration markets, as well as, improving the transportation of food. The FSP was embedded in the national poverty reduction strategy and contained the Productive Safety Net Program (PSNP), which similarly to the ADLI, targeted small-scale farmers. Although crop production intensified during this period (i.e., cereal production increased from 6.1 million metric tons in 1990 to 10.1 million metric tons [36]), food insecurity and malnutrition remained prevalent, in which 32.9% of children were underweight in 2005 [37].

The National Nutrition Strategy (NNS) put nutrition on the national agenda by being the first nutrition policy document approved by the Council of Ministers of the Ethiopian government. The NNS was a key nutrition policy document developed under the motivation to prevent malnutrition and improve population nutritional status [38]. The National Nutrition Programme (NNP) was developed to implement the NNS. The NNP was successful in introducing nutrition in the policy landscape and since then nutritional-related indicators such as stunting have been implemented into policies including The Growth and Transformation Plan. Modest improvements in nutrition trends were seen during the time the NNS and NNP were in place, in which the percentage of children underweight decreased to 28.7% in 2011 [39]. The NNP was revised in 2013 and subsequently in 2016, with the latter emphasizing the importance of leveraging nutrition in multiple sectors including agriculture. The Ministry of Agriculture was given the mandate to mainstream nutrition in the agriculture sector which involved strengthening nutrition linkages with agricultural subsectors, conduct nutrition training, and support nutrition linkages in agricultural programs and policies. This was further emphasized in The Nutrition Sensitive Agriculture Strategy which recognized non-linear agriculture–nutrition pathways and vowed to act on different routes including food production and productivity, agricultural income, and women’s empowerment [40].

Ghana

The government of Ghana implemented several policies to reduce poverty, ensure food security and improve nutrition and health (Table 3). The government of Ghana introduced Accelerated Agricultural Growth and Development Strategy (AAGDS) I & II in the mid-1990s as policies to forge linkages in the value chain. Food and industrial crop production to increase economic growth rather than to improve nutrition outcomes were the focus of the AAGDS I and II. AAGDS II policy was later replaced by the first Food and Agriculture Sector Development Policy (FASDEP I) in 2002 aimed at modernizing the agriculture sector in Ghana [41, 42]. After implementing FASDEP I for four years, it was revised to FASDEP II to address the limitations of FASDEP I that included improper targeting of poor smallholder farmers who had limited access to credit and technology, proper infrastructure, and markets [42]. Although the FASDEP II lacks explicit nutrition-related goals/objectives, the policy does include a focus on improving food security through the production of at most 5 staple crops. Additionally, the government introduced the Regenerative Health and Nutritional Programme (RHNP) to address diet-related diseases especially non-communicable chronic diseases (NCDs) in 2007. The program emphasized healthy eating and exercise and emphasized collaboration with key partners including the Ministry of Food and Agriculture. However, most of the foods recommended by the program were not readily available to poor households who face nutritional deficiency [43]. In 2013, the government introduced the National Nutrition Policy (NNP) aimed at developing an evidence-based national intervention to address nutrient deficiency [44]. The NNP recognizes linkages between nutrition and agriculture and proposed a multi-sectoral technical committee on nutrition to bring together ministries among others to coordinate policy issues and directions for nutrition.

According to a recent report, the implementation of the policies has decreased hunger by 75% since the 1990s and, the number of malnourished people has decreased from 7 to 1 million in 2015 [45, 46]. Ghana is one of the few countries in Africa to achieve the Millennium Development Goal 1 (eradicate extreme poverty and hunger) by reducing poverty by half [42]. However, the problem of overnutrition has emerged resulting in high cases of overweight/obesity. According to the 2014 demographic and health survey, 40% of women in Ghana were overweight/obese [45] and the rate is even higher (49%) in urban areas [47]. Even though food and nutritional security have significantly improved over the years, micronutrient deficiency is high especially in iron deficiency among girls, women, and children as well as increasing stunting, overweight, and obesity in Ghana [45]. Therefore, addressing nutritional deficiency requires a concerted effort by the government to introduce policies that will not only address food insecurity but also address nutritional insecurity.

Malawi

Despite significant crop production in the agriculture sector, Malawi continued to experience high levels of malnutrition and food insecurity in the 1970s and 1980s in which about 55% of children were malnourished [48]. To address these challenges, the government adopted the first Food Security and Nutrition Policy in 1990 (Table 4). The policy’s limited focus on nutrition led to the development of several subsequent nutrition policies. This includes the Food and Nutrition Policy which was split into two separate policy documents: Food Security Policy and National Nutrition Policy. The Food Security Policy was adopted in 2006 and included multiple strategies to improve food availability, access, and stability. However, nutritional issues remained prevalent before and after these policies were implemented in which stunting in children mildly decreased from 52.5% in 2004 to 47.1% in 2010 [49, 50]. The subsequently developed nutrition policy, the National Nutrition Policy and Strategic Plan, contained more nutrition-related objectives and places greater attention on the agriculture sector in promoting dietary diversity yet lacks strategies to increase market access for the most vulnerable. Although the prevalence of malnutrition remained high after the implementation of these policies, Malawi experienced significant progress in improving nutritional status in which stunting in children decreased from 52.5% in 2004 to 37.1% in 2015 [49, 51]. The National Multi-Sector Nutrition Policy 2018–2022 was developed following the review of the National Nutrition Policy and Strategic Plan [52]. This policy uses a multi-sectoral and evidence-based approach in improving nutrition outcomes and therefore places a high commitment to adopting nutrition-sensitive interventions. Since independence, the Malawi government has not released a comprehensive agricultural policy until recently in 2016 when the National Agricultural Policy was adopted. The National Agricultural Policy recognizes food and nutrition security as an area of high concern and states the need for diversification by prioritizing the commercialization of smallholder farmers [53]. Previously, agricultural strategies have been embedded within key development strategies such as The Malawi Growth and Development Strategies. The Malawi Growth and Development Strategies have undergone multiple revisions and its third revision is currently in place until 2022.

Nigeria

A common trend among the early agriculture and nutrition policies in Nigeria was the promotion of food security in the absence of nutrition-specific priorities. This was observed in both The Agricultural Policy for Nigeria (1998) and The New Nigerian Agricultural Policy which was subsequently adopted in 2001 (Table 5). Ashaolu et al. [54] found that though food security was particularly pronounced in The New Nigerian Agricultural Policy, not all dimensions of food security were adequately addressed. In addition to The New Nigerian Agricultural Policy, a nutrition policy was developed in 2001 called the National Policy on Food and Nutrition in Nigeria and included a commitment to address major food and nutrition challenges using a multi-sectoral approach. However, the role of the agriculture sector in improving food security and nutrition was limited in scope and was only emphasized in strategies to increase food access [55]. As a result of the policy’s limitations, the policy had little to no effect in improving population-level nutritional outcomes [56]. As such stunting trends remained fairly static before and after the implementation of these policies in which stunting in children modestly decreased from 48.7% in 1990 to 42.4% in 2003 [57, 58]. This led to the revision of the National Policy on Food and Nutrition in 2016, which similarly took a multi-sector approach to address emerging issues such as diet-related NCDs, and contained nutrition-sensitive agricultural strategies [56, 59]. Food and nutritional security were recognized in the Agriculture Transformation Agenda (ATA) and were to be achieved through production specialization of key commodities. However, an econometric analysis by Ecker et al. [60] found that farm production diversity increased between 2011 and 2016 despite the ATA’s vision of production specialization. Following the ATA, three major policies were developed in 2016 including the Agriculture Promotion Policy, Agriculture Sector Food Security and Nutrition Strategy, and the previously mentioned National Policy on Food and Nutrition. These policies signified steps forward in recognizing the importance of the agriculture sector’s role in improving the nutrition situation in Nigeria. However, poor implementation and lack of funding have constrained Nigeria from experiencing these benefits [61].

South Africa

The White Paper on Agriculture (1995) was a policy document developed by the Ministry of Agriculture and contained a vision for South African agriculture that focused on creating a strong economy from a market-directed farming sector (Table 6). The policy signaled a priority shift from food self-sufficiency to food security. However, the vision to improve food security was implicitly recognized and was nested within agricultural sector strategies of increasing food production. A similar approach was seen in the 1998 Discussion Document on Agricultural Policy in South Africa and policies that were later developed including the 2012 Integrated Growth and Development Plan. Similarly, the policies were limited in addressing nutrition and failed to include nutrition-related objectives. The Integrated Food Strategy of South Africa (2002) recognized the potential for agriculture to contribute to better nutrition through agricultural efforts to increase food production, food access, and income generation [62]. The implementation of these policies resulted in minimal change in nutritional trends. For example, stunting rates in children remained high in which a modest decrease from 28.7% to 24.9% was observed from 1994 to 2008 [63]. A review of the Integrated Food Strategy led to the development of the National Policy on Food and Nutrition Security in 2014, which contained a commitment to ensure better coordination between sectors and emphasized the agricultural sector to increase food production. The Agricultural Policy Action Plan was adopted in 2015 and focused on facilitating several agricultural value-chains to meet the objectives of development plans such as improving food security, job creation, production value, growth potential, and trade balance [64]. Although nutrition is receiving greater attention in more recent policies, the ways to achieve improved nutritional outcomes are often missing, for example strategies that promote agricultural diversification, food processing to retain nutrient value, and food storage of nutrient-rich foods [30].

Policy challenges

Limited attention on micronutrient-rich food production

The agricultural policies reviewed rely heavily on increasing agricultural production of staple commodities such as cereal crops and lack attention to opportunities to address dietary diversity and micronutrient malnutrition. For example, Ghana's FASDPE II, Ethiopia's Agriculture Policy and Investment Framework (PIF), and South Africa’s Discussion Document on Agricultural Policy all seek to diversify crop production, but with a focus on boosting agricultural commercialization rather than enhancing nutrition. The overemphasis of staple crop production such as maize is also seen in policies and programs in Malawi [65]. This is highlighted by the Farm Income Subsidy Program (FISP) under Malawi’s Growth and Development Strategy, which subsidizes fertilizers and improved seeds mainly for maize production. The FISP was central to the growth of the agricultural sector but has been criticized as being inefficient and expensive taking up between 50 and 75% of Malawi’s agriculture budget annually leaving little room for alternative interventions such as produce diversification [65]. In addition, the program has resulted in a market dominated by maize leaving farmers unable to profitably sell their produce and therefore limiting their ability to sustainably produce nutritious foods. Although the program contributed to increases in maize output and maize self-sufficiency, food insecurity has prevailed, and diets remain poorly diversified [66].

Lack of agriculture policies with nutrition priorities

The primary focus of the majority of agricultural policies is to increase agricultural production and productivity in an effort to bolster economic opportunities and increase the pace of poverty reduction. Thus, measurable nutritional-related objectives are often missing from these policies (i.e., Malawi’s National Agricultural Policy) making it difficult to measure the progress and success of policy interventions. Other policies reviewed that lacked nutrition-related objectives includes Ethiopia’s ADLI and PIF, as well as, the Agricultural Policy for Nigeria.

Food security was recognized as a key priority within the majority of agriculture policies with the implicit assumption that food security will lead to better nutritional outcomes. Although food security and nutrition are closely interrelated, the focus on food self-sufficiency is inadequate in guaranteeing optimal nutritional status and/or food security. This is seen in South Africa as the country is considered food self-sufficient, yet struggles with household food security, inequities in food access, and malnutrition [67]. Achieving food security goes beyond merely meeting food self-sufficiency and requires food to not only be physically available but also accessible and usable, as well as for these conditions to be stable over time. Yet, policies fail to simultaneously address every pillar of food security and are preoccupied with increasing the quantity of food at the expense of improving food quality.

The lack of nutrition goals and objectives within agriculture policies could be related to separate and countervailing silos across sectors that are embedded within a weak enabling environment. The Leveraging Agriculture for Nutrition in East Africa study highlighted the general lack of knowledge on how agriculture can contribute to nutrition beyond increasing productivity [68]. A similar multi-country study found that stakeholders in South Africa demonstrated a similar puzzlement highlighted by comments like: “why should agriculture be responsible for nutrition?” and “agriculture has become a business and its main purpose is (and should remain) profitability and increased production” [15]. These perceptions translate into the lack of political will which can further constrain policy implementation.

Weak multi-sector collaboration to improve nutrition

A weak enabling environment to leverage agriculture to improve nutrition is partly due to the ineffective collaboration between sectors and stakeholders during policy planning, monitoring, and implementation. In all five countries, policy implementation of nutrition components was limited as sectors failed to ensure multi-sector collaboration. For example, Ethiopia’s NNP included a Nutrition Coordination Body co-chaired by the Ministry of Agriculture, yet sectors failed to mainstream nutrition into their sectoral strategic plans [69]. Similarly, in The Integrated Food Strategy of South Africa 2002, multi-sector coordination was recognized yet unsuccessful as the Department of Agriculture carried out the majority of implementation [70,71,72]. This was also seen in Nigeria’s National Policy on Food and Nutrition recognized the agriculture sector in policy strategies yet, did not have a clear institutional framework for engaging the sector.

Weak capacity for policy implementation

Inadequate capacity in the form of training/knowledge, financial constraints, and human resources are barriers to addressing nutrition through agriculture [68, 73]. These challenges are even seen in policies that incorporate nutrition objectives but may not be implemented effectively due to weak capacity. For example, the implementation of Ethiopia’s National Nutrition Programme fell short as ministries lacked an effective organizational structure to integrate nutrition into their core activities, did not allocate a sector budget for nutrition plans, and lacked mechanisms for nutrition data triangulation [69]. Similarly, Nigeria’s National Policy on Food and Nutrition lacked strong coordination and monitoring systems for policy implementation [56]. In addition, South Africa’s Integrated Food Strategy of South Africa suffered from poor coordination and weak institutional framework which led to ineffective policy implementation. Even when evidence is available, it was found that policy makers lack the capacity to link, analyze and interpret data thereby limiting its translation into policy [68].

Lack of market access for smallholder farmers

Nutrition-sensitive agriculture can address issues related to access including limited market access for smallholder farmers. In the policies reviewed, limited attention was given to interventions to expand market access for smallholder farmers and on the barriers withholding farmers from integrating into markets. The commercialization of agriculture was a long-standing goal in South Africa as stated in the White Paper of Agriculture published in 1995. The White Paper advocated for providing support services to allow farmers to move into commercial farming [74]. However, researchers have shown that commercialization may hamper smallholder farmer productivity if barriers to market participation are not appropriately addressed [75]. These barriers can include unavailability of credit, lack of institutional support, high transaction costs, lack of training, inadequate property rights, and poor market access [76]. Yet these constraints were given limited attention within the policies reviewed including Malawi’s Food Security Policy and National Nutrition Policy and Strategic Plan. Even in policies that do include the priority of expanding market access for smallholder farmers such as Malawi’s National Agriculture Policy 2016, improving market access to nutrient-rich foods was missing.

Discussion

A review of the agricultural policies in Ethiopia, Ghana, Malawi, Nigeria, South Africa uncovers several critical paths and policy recommendations to strengthen nutrition-sensitive agriculture and stave off nutrition transition. First, governments must support policies that promote the production and diversification of micronutrient-rich foods. Multiple studies have demonstrated a relationship between agricultural production and dietary diversity [73, 77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84]. Policymakers are beginning to recognize the need to move beyond the production of staple crops and integrate strategies to promote micronutrient-rich foods. For example, Ethiopia and Nigeria’s nutrition-sensitive agricultural strategies [40, 85] have recognized the benefits of leveraging agriculture to increase the production of nutritious foods. Studies have demonstrated how, for instance, African Indigenous Leafy Vegetables (AILVs), tubers, and cereals such as sorghum and millet can address the nutritional needs of people [6, 43, 86, 87]. However, parents prefer to give their children bread and soda because of negative perception regarding African Indigenous Food Crops (AIFCs), which has little to do with nutrition [6]. AIFCs are associated with poverty and considered poor peoples’ food. Consequently, many AIFCs are going extinct due to a lack of cultivation, consumption, and inadequate knowledge of preparation among the youth [6]. Hence, future policies should focus on promoting agricultural diversity to improve the food systems while simultaneously remediating the negative impacts of the nutritional transition.

Secondly, governments should provide strategies to strengthen value chains for nutritious foods. Growth in population, urbanization, and incomes are driving the food system transformation in SSA towards the modernization of food production, processing, and distribution and increased value chain coordination [88]. Research has shown that agricultural value chains can be an essential mechanism in promoting the production and consumption of nutritious foods [89, 90]. However, few policies focus on improving nutrition through the performance of value chains, as agricultural policies in many African countries are still focused on industrializing food value chains and neglect micronutrient-rich vegetables and fruits [91]. For example, studies have suggested that scaling up pulse value chains in sub-Saharan Africa can positively affect nutritional and economic sustainability yet receive limited policy attention compared with staple cereal crops [92]. In addition, traditional cash crops (i.e., tea, tobacco, palm oil) destined for the international market have been a significant focus in agriculture policies. A policy shift from traditional cash crops to food crops as cash crops in the local market is needed. The rise in the urban population creates a new wave of consumers, therefore, policy focused on food value-chains can be beneficial. Policies must contain clear nutrition goals for value chains to produce nutritious foods. An enabling environment to develop value chains for nutrition can be encouraged through creating incentives for actors throughout the chain and provide services for farmers and businesses to overcome challenges along the supply chain [93].

Thirdly, governments must improve market access for smallholder farmers through effective strategies and policies to strengthen nutrition-sensitive agriculture. Physical and economic proximity to markets can increase incomes from selling farm produce and increased physical access and availability to foods with higher nutrient content and higher dietary diversity [94]. Studies have demonstrated a positive relationship between market access and household dietary diversity and nutrition [95,96,97,98]. These findings call for future policies to incorporate strategies to increase market access by improving the conditions for successful market participation. This includes infrastructure development to reduce travel times to markets and service delivery models specific to connected and remote farms [99]. In addition, there is a need for policies to address eliminating barriers for entry into markets. These policies include reducing transaction costs associated with poor rural infrastructure, increasing access to information and finance, capacity building for effective knowledge uptake, and increasing support for producer organizations to link farmers to food processing facilities and retailers [100, 101].

Finally, multi-sector collaboration must be strengthened as it fosters an enabling environment for successfully implementing nutrition-sensitive policies and programs. Multi-sector nutrition programs enable stakeholders to address the multifaceted nature of nutrition challenges by integrating program design, implementation, and monitoring across sectors. Establishing nutrition as a key policy priority area in national policy documents is essential in enabling multi-sector collaboration and improved nutrition outcomes [102]. Although recent policy documents have recognized the role agriculture can play in improving nutritional outcomes, multi-sectoral objectives and strategies remain minimal. The appropriate responses to multi-sectoral challenges depend on the source of the problem and the context [103]. For example, the World Bank [104] recommends a “think multisectorally, act sectorally” response that promotes intersectoral dialogue at each stage of intervention development while ensuring each sector is held accountable for their results through effective coordination and monitoring and evaluation. Strategies to address challenges in differing stakeholder perspectives and disagreements include collaborative problem-solving methods and capacity building regarding broker agreements, conflict resolution, and relationship and trust building [103, 105,106,107]. In Ethiopia, investment in education is prioritized to address the shortage of nutrition policy makers and experts [102].

Conclusion

The review of past and current national policies relevant to agriculture and food in Ethiopia, Ghana, Malawi, Nigeria, and South Africa demonstrates that nutrition-sensitive agriculture had received scant attention. Several reasons for this situation include limited attention to micronutrient-rich food production, weak multi-sector collaboration to improve nutrition, inadequate capacity for policy implementation, and insufficient market access for smallholder farmers. However, policymakers are beginning to recognize the importance of leveraging the agricultural sector to address issues of malnutrition in SSA. This has led to revision and development of new policies such as Ethiopia’s Nutrition Sensitive Agriculture Strategy and Nigeria’s Agricultural Sector Food and Security Nutrition Sector that prioritize nutrition-sensitive strategies as the main drivers in overcoming malnutrition. This follows policies from other countries in SSA that have been successful in integrating a focus on nutrition-sensitive agriculture. For example, Benin’s Action Plan for Food and Nutrition in Agricultural Sector (2015) and Zambia’s National Agriculture Investment Plan (2013) contains a strong focus on nutrition-sensitive agriculture by including explicit nutrition objectives, promoting the production of diverse food crops, working in partnership with other sectors, and in expanding market access for vulnerable groups [31, 108]. By incorporating recommended policy measures such as greater policy coordination across sectors and stakeholders, improved policy implementation methods, strategies to increase producer market access, and an overall prioritization of nutritious foods, countries can start to inch forward in improving the nutritional status of their population.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

References

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020 [Internet]. FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO; 2020 [cited 2020 Sep 3]. Available from: http://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/ca9692en.

FAO. COVID-19 and malnutrition: situation analysis and options in Africa [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 Apr 18]. Available from: http://www.fao.org/3/ca9896en/CA9896EN.pdf.

UNICEF, WHO, World Bank. Levels and trends in child malnutrition: Key findings of the 2018 Edition of the Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2021 Jun 27]. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/resources/levels-and-trends-in-child-malnutrition-2018/.

WHO, Regional Office for Africa. Atlas of African health statistics 2018: Universal health coverage and the sustainable development goals in the WHO African Region [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2021 Apr 26], p. 111. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/311460.

Carroll GJ, Lama SD, Martinez-Brockman JL, Pérez-Escamilla R. Evaluation of nutrition interventions in children in conflict zones: a narrative review. Adv Nutr. 2017;8(5):770–9.

Demi SM. African indigenous food crops: Their roles in combating chronic diseases in Ghana [Internet]. University of Toronto; 2014 [cited 2021 Apr 18]. Available from: https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/handle/1807/68528.

Pingali P, Aiya A, Abraham M, Rahman A. The nutrition transformation: from undernutrition to obesity. In: Pingali P, Aiyar A, Abraham M, Rahman A, editors. Transforming food systems for a rising India. Berlin: Springer; 2019.

Popkin BM. Nutritional patterns and transitions. Popul Dev Rev. 1993;19(1):138–57.

Demi SM. Reclaiming cultural identity through decolonization of food habits. In: Wane N, Todorova M, Todd K, editors. Decolonizing the spirit in education and beyond: Resistance and solidarity. Berlin: Springer; 2019.

Lang T, Barling D, Caraher M. Food Policy Integrating health, environment and society. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009. p. 282.

OECD. Agricultural policy [Internet]. OECD. 2020 [cited 2020 Apr 1]. Available from: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/agriculture-and-food/agricultural-policy/indicator-group/english_22d89f8c-en.

Story M, Kaphingst KM, Robinson-O’Brien R, Glanz K. Creating healthy food and eating environments: policy and environmental approaches. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29(1):253–72.

Ezezika O, Gong J, Abdirahman H, Sellen D. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of large-scale nutrition interventions in Africa: a scoping review. Glob Implement Res Appl. 2021;1(1):38–52.

Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition. How can agriculture and food system policies improve nutrition? [Internet]. London,UK; 2014 [cited 2020 Jun 1]. Available from: http://www.glopan.org/sites/default/files/Global%20Panel%20Technical%20Brief%20Final.pdf.

Fanzo J, Cohen M, Sparling T, Olds T, Cassidy M. The Nutrition Sensitivity of Agriculture and Food Policies [Internet]. Columbia University; 2014 [cited 2020 May 2]. Available from: http://unscn.org/files/Publications/Country_Case_Studies/UNSCN-Executive-Summary-Booklet-Country-Case-Studies-Nairobi-Meeting-Report.pdf.

Nyakurwa CS, Gasura E, Mabasa S. Potential for quality protein maize for reducing protein energy undernutrition in maize dependent Sub-Saharan African countries: a review. Afr Crop Sci J. 2017;25(4):521–37.

Kinabo J. The Policy Environment for Linking Agriculture and Nutrition in Tanzania [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2020 Aug 26]. Available from: http://repository.businessinsightz.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12018/2740/The%20Policy%20Environment%20for%20Linking%20Agriculture%20and%20nutrition.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Lencucha R, Pal NE, Appau A, Thow A-M, Drope J. Government policy and agricultural production: a scoping review to inform research and policy on healthy agricultural commodities. Glob and Health. 2020;16(1):11.

Pawlak K, Kołodziejczak M. The role of agriculture in ensuring food security in developing countries: considerations in the context of the problem of sustainable food production. Sustainability. 2020;12(13):5488.

Ruel MT, Quisumbing AR, Balagamwala M. Nutrition-sensitive agriculture: what have we learned so far? Glob Food Sec. 2018;1(17):128–53.

Headey D, Chiu A, Kadiyala S. Agriculture’s role in the Indian enigma: help or hindrance to the crisis of undernutrition? Food Sec. 2012;4(1):87–102.

Herforth A, Harris J. Understanding and Applying Primary Pathways and Principles. [Internet]. Arlington,VA: USAID/Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) Project. Improving Nutrition through Agriculture Technical Brief Series. 2014 [cited 2020 Aug 25]. Available from: https://www.spring-nutrition.org/sites/default/files/publications/briefs/spring_understandingpathways_brief_1.pdf.

Jaenicke H, Virchow D. Entry points into a nutrition-sensitive agriculture. Food Sec. 2013;5(5):679–92.

Kadiyala S, Harris J, Headey D, Yosef S, Gillespie S. Agriculture and nutrition in India: mapping evidence to pathways: agriculture-nutrition pathways in India. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2014;1331(1):43–56.

Pinstrup-Andersen P. Can agriculture meet future nutrition challenges? Eur J Dev Res. 2013;25(1):5–12.

Ruel MT, Alderman H. Nutrition-sensitive interventions and programmes: how can they help to accelerate progress in improving maternal and child nutrition? The Lancet. 2013;382(9891):536–51.

Gillespie S, Harris J, Kadiyala S. The Agriculture-Nutrition Disconnect in India: What Do We Know? [Internet]. International Food Policy Research Institute; 2012 [cited 2020 Mar 22], p. 56. Available from: https://www.ifpri.org/cdmref/p15738coll2/id/126958/filename/127169.pdf.

de Brauw A, Eozenou P, Moursi M. Programme participation intensity and children’s nutritional status: evidence from a randomised control trial in Mozambique. J Dev Stud. 2015;51(8):996–1015.

Kumar N, Nguyen PH, Harris J, Harvey D, Rawat R, Ruel MT. What it takes: evidence from a nutrition- and gender-sensitive agriculture intervention in rural Zambia. J Dev Eff. 2018;10(3):341–72.

Schönfeldt H, Hall N, Pretorius B. Nutrition-sensitive agricultural development for food security in Africa: a case study of South Africa. In: Appiah-Opoku S, editor. International development. London: InTechopen; 2017.

Aryeetey R, Covic N. A review of leadership and capacity gaps in nutrition-sensitive agricultural policies and strategies for selected countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. Food Nutr Bull. 2020;41(3):380–96.

Food and Agriculture Organization. Designing nutrition-sensitive agriculture investments. Rome: FAO; 2015. p. 4–5.

The World Bank. Ethiopia - Prevalence of underweight, weight for age (% of children under 5) [Internet]. The World Bank. 2022 [cited 2022 Aug 29]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.MALN.ZS?locations=ET.

Keeley J, Scoones I. Knowledge, power and politics: the environmental policy-making process in Ethiopia. J Mod Afr Stud. 2000;38(1):89–120.

Stellmacher T, Kelboro G. Family farms, agricultural productivity, and the terrain of food (In)security in Ethiopia. Sustainability. 2019;11(18):4981.

The World Bank. Ethiopia - Cereal production (metric tons) [Internet]. The World Bank. 2022 [cited 2022 Aug 29]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/AG.PRD.CREL.MT?locations=ET.

Central Statistical Agency/Ethiopia and ORC Macro. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2005 [Internet]. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2005 [cited 2022 Aug 29]. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR179/FR179[23June2011].pdf.

The Federal Democratic of Ethiopia. National Nutrition Strategy [Internet]. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2008 Jan [cited 2020 Apr 27]. Available from: https://extranet.who.int/nutrition/gina/sites/default/filesstore/ETH%202008%20National%20Nutrition%20Strategy_1.pdf.

Central Statistical Agency/Ethiopia and ICF International. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2011. [Internet]. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Central Statistical Agency and ICF International.; 2012 [cited 2022 Aug 29]. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR255/FR255.pdf.

Ministry of Agriculture and Natural Resource, Ministry of Livestock and Fisheries. Nutrition Sensitive Agriculture Strategy [Internet]. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2016 [cited 2021 Jun 9]. Available from: http://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/eth174139.pdf.

Ministry of Food and Agriculture. Food and Agriculture Sector Development Policy (FASDEP) [Internet]. Accra, Ghana; 2002 [cited 2021 Apr 18]. Available from: https://extranet.who.int/nutrition/gina/sites/default/filesstore/GHA%202002%20Food%20and%20agriculture%20sector%20development%20policy1.pdf.

Ministry of Food and Agriculture. Food and Agriculture Sector Development Policy (FASDEP II) [Internet]. Accra, Ghana; 2007 [cited 2021 Apr 18]. Available from: https://extranet.who.int/nutrition/gina/sites/default/filesstore/GHA%202007%20Food%20and%20agriculture%20sector%20development%20policy2.pdf.

Demi SM. Using African indigenous food crops as local remedy against chronic diseases: Implications for healthcare systems in Ghana. In: Fymat AL, Kapalanga J, editors. Science Research and Education in Africa: Proceedings of a Conference on Science Advancement. Cambridge Scholars Publishing; 2017.

Government of Ghana. National Nutrition Policy [Internet]. Accra, Ghana; 2016 [cited 2021 Apr 18]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/ghana/media/1311/file/UN712528.pdf.

World Food Programme. Draft Ghana country strategic plan (2019-2023) [Internet]. Rome, Italy; 2018 [cited 2021 Apr 18]. Available from: https://executiveboard.wfp.org/document_download/WFP-0000074182.

World Food Programme. The Ghana Zero Hunger strategic review [Internet]. Accra, Ghana; 2017 [cited 2021 Apr 26]. Available from: https://www.wfp.org/publications/ghana-zero-hunger-strategic-review.

Government of Ghana. National Nutrition Policy for Ghana 2013–2017. [Internet]. Accra, Ghana; 2013 [cited 2021 Apr 26]. Available from: http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/gha145267.pdf.

Quinn V, Chiligo M, Gittinger JP. Malnutrition, household income and food security in rural Malawi. Health Policy Plan. 1990;5(2):139–48.

National Statistical Office - NSO/Malawi and ORC Macro. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2004 [Internet]. Calverton, Maryland: NSO/Malawi and ORC Macro; 2005 [cited 2022 Aug 29]. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR175/FR-175-MW04.pdf.

National Statistical Office - NSO/Malawi and ICF Macro. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2010 [Internet]. Zomba, Malawi: NSO/Malawi and ICF Macro; 2010 [cited 2022 Aug 29]. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR247/FR247.pdf.

National Statistical Office - NSO/Malawi and ICF. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2015-16 [Internet]. Zomba, Malawi: NSO and ICF; 2017 [cited 2022 Aug 29]. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR319/FR319.pdf.

Government of Malawi - Department of Nutrition, HIV, and AIDS. National Multi-Sector Nutrition Policy 2018-2022 [Internet]. Malawi; 2018 [cited 2020 Apr 20]. Available from: https://extranet.who.int/nutrition/gina/sites/default/filesstore/MWI_2018_National-Multi-Sector-Nutrition-Policy.pdf.

Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation and Water Development. National Agriculture Policy [Internet]. Lilongwe, Malawi; 2016 [cited 2020 Apr 20]. Available from: https://www.canr.msu.edu/fsp/countries/malawi/malawi_national_agriculture_policy_25.11.16.pdf.

Ashaolu TJ, Olayinka I, Twumasi-Ankrah S. The New Nigerian agricultural policy: efficient for food security? J Food Sci and Technol. 2016;2(4):1–6.

Nigerian Academy of Science. Agriculture for Improved Nutrition of Women and Children in Nigeria-Policy Considerations [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2020 Mar 30]. Report No.: 2. Available from: http://nas.org.ng/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Agric-nutrition-policy-brief-2.pdf.

Ministry of Budget and National Planning. National Policy on Food and Nutrition in Nigeria [Internet]. Abuja, Nigeria; 2016 [2020 Apr 7]. Available from: https://ngfrepository.org.ng:8443/jspui/bitstream/123456789/3151/1/NATIONAL%20POLICY%20ON%20FOOD%20AND%20NUTRITION%20IN%20NIGERIA.pdf.

Federal Office of Statistics/Nigeria and Institute for Resource Development - IRD/Macro International. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 1990. [Internet]. Columbia, Maryland, USA: Federal Office of Statistics/Nigeria and IRD/Macro International.; 1992 [cited 2022 Aug 29]. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR27/FR27.pdf.

National Population Commission - NPC/Nigeria and ORC Macro. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2003 [Internet]. Calverton, Maryland: ORC Macro; 2004 [cited 2022 Aug 29]. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR148/FR148.pdf.

Oluwasanu M, Oladunni O, Oladepo O. Multisectoral approach and WHO ‘Bestbuys’ in Nigeria’s nutrition and physical activity policies. Health Promot Int. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daaa009.

Ecker O, Hatzenbuehler PL, Mahrt K. Transforming agriculture for improving food and nutrition security among Nigerian farm households. Washington: International Food Policy Research Institute; 2018.

Morgan AE, Fanzo J. Nutrition transition and climate risks in Nigeria: moving towards food systems policy coherence. Curr Envir Health Rpt. 2020;7(4):392–403.

Agriculture Republic of South Africa. The Integrated Food Security Strategy for South Africa [Internet]. Pretoria, South Africa; 2002 [cited 2020 Apr 2]. Available from: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/foodpol0.pdf.

The World Bank. South Africa - Prevalence of stunting, height for age (% of children under 5) [Internet]. The World Bank. 2022 [cited 2022 Aug 29]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.STNT.ZS?locations=ZA.

Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Agricultural Policy Action Plan (APAP) 2015-2019 [Internet]. Pretoria, South Africa; 2014 [cited 2020 Apr 1]. Available from: http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/saf191581.pdf.

White SA. A TEEBAgriFood Analysis of the Malawi Maize Agri-food System [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Aug 26]. Available from: https://futureoffood.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/GA_TEEB_MalawiMaize201903.pdf.

Kerr RB. Seed struggles and food sovereignty in northern Malawi. Peasant Stud. 2013;40(5):867–97.

Clapp J. Food self-sufficiency: making sense of it, and when it makes sense. Food Policy. 2017;1(66):88–96.

Hodge J, Herforth A, Gillespie S, Beyero M, Wagah M, Semakula R. Is there an enabling environment for nutrition-sensitive agriculture in East Africa?: stakeholder perspectives from Ethiopia, Kenya, and Uganda. Food Nutr Bull. 2015;36(4):503–19.

Government of Ethiopia. National Nutrition Program [Internet]. Ethiopia; 2016 [cited 2020 Apr 27]. Available from: http://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/eth190946.pdf.

Candel JJL. Diagnosing integrated food security strategies. NJAS-Wagen J Life Sci. 2018;84:103–13.

Drimie S, Ruysenaar S. The integrated food security strategy of South Africa: an institutional analysis. Agrekon. 2010;49(3):316–37.

McLachlan M, Landman AP. Nutrition-sensitive agriculture – a South African perspective. Food Sec. 2013;5(6):857–71.

Fanzo J, Hunter D, Borelli T, Mattei F. Diversifying food and diets: using agricultural biodiversity to improve nutrition and health. Abingdon: Earthscan from Routledge; 2013. p. 368.

Makhura MT, Coetzee G, Goode FM. Commercialization as a strategy for reconstruction in agriculture. Agrekon. 1996;35(1):35–40.

Nwafor C, Westhuizen C van der. Prospects for Commercialization among Smallholder Farmers in South Africa: A Case Study. J Rural Soc Sci [Internet]. 2020 Jan 22 [cited 2020 Aug 27];35(1). Available from: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/jrss/vol35/iss1/2.

Thamaga-Chitja JM, Morojele P. The context of smallholder farming in South Africa: towards a livelihood asset building framework. J Hum Ecol. 2014;45(2):147–55.

Jones AD, Shrinivas A, Bezner-Kerr R. Farm production diversity is associated with greater household dietary diversity in Malawi: Findings from nationally representative data. Food Policy. 2014;1(46):1–12.

Waha K, van Wijk MT, Fritz S, See L, Thornton PK, Wichern J, et al. Agricultural diversification as an important strategy for achieving food security in Africa. Glob Change Biol. 2018;24(8):3390–400.

Pellegrini L, Tasciotti L. Crop diversification, dietary diversity and agricultural income: empirical evidence from eight developing countries. Can J Dev Stud. 2014;35(2):211–27.

Remans R, Flynn DFB, DeClerck F, Diru W, Fanzo J, Gaynor K, et al. Assessing nutritional diversity of cropping systems in African villages. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(6):e21235.

Powell B, Thilsted SH, Ickowitz A, Termote C, Sunderland T, Herforth A. Improving diets with wild and cultivated biodiversity from across the landscape. Food Sec. 2015;7(3):535–54.

Kumar N, Harris J, Rawat R. If they grow it, will they eat and grow? evidence from Zambia on agricultural diversity and child undernutrition. J Dev Stud. 2015;51(8):1060–77.

Dillon A, McGee K, Oseni G. Agricultural production, dietary diversity and climate variability. J Dev Stud. 2015;51(8):976–95.

Adjimoti GO, Kwadzo GT-M. Crop diversification and household food security status: evidence from rural Benin. Agric Food Secur. 2018;7(1):82.

The Federal Republic of Nigeria. Agricultural Sector Food Security and Nutrition Strategy 2016 – 2025 [Internet]. Nigeria; 2017 [cited 2020 Mar 30]. Available from: http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/nig201549.pdf.

Demi SM. Assessing indigenous food systems and cultural knowledges among smallholder farmers in Ghana: Towards environmental sustainability education and development [Internet]. [Toronto, Canada]: University of Toronto; 2019. Available from: https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/108201/1/Demi_Suleyman_M_201911_PhD_thesis.pdf.

Raschke V, Cheema B. Colonisation, the new world order, and the eradication of traditional food habits in east Africa: historical perspective on the nutrition transition. Public Health Nutr. 2007;11(7):662–74.

Haggblade S. Modernizing African agribusiness: reflections for the future. J Agribus Dev Emerg Econ. 2011;3(1):10–30.

Allen S, de Brauw A. Nutrition sensitive value chains: theory, progress, and open questions. Glob Food Sec. 2018;1(16):22–8.

Gelli A, Hawkes C, Donovan J, Harris J, Allen S, Brauw A, et al. Value chains and nutrition: a framework to support the identification, design, and evaluation of interventions. Int Food Policy Res Ins. 2015. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2564541.

Pingali P. Agricultural policy and nutrition outcomes—getting beyond the preoccupation with staple grains. Food Sec. 2015;7(3):583–91.

Clark L. Implementing multilevel nutrition-sensitive food security frameworks in sub-Saharan Africa: challenges and opportunities for scaling up pulses in Ethiopia. J Rural Soc Sci. 2017;31(1):5.

Hawkes C, Ruel M. Value Chains for Nutrition. In: Fan S, Pandya-Lorch R, editors. Reshaping agriculture for nutrition and health. Washington: International food policy research institute; 2012. p. 73–81.

Barrett CB. Smallholder market participation: concepts and evidence from eastern and southern Africa. Food Policy. 2008;33(4):299–317.

Chege CGK, Andersson CIM, Qaim M. Impacts of supermarkets on farm household nutrition in kenya. World Dev. 2015;72:394–407.

Gupta S, Vemireddy V, Pingali PL. Nutritional outcomes of empowerment and market integration for women in rural India. Food Secur. 2019;11(6):1243–56.

Koppmair S, Kassie M, Qaim M. Farm production, market access and dietary diversity in Malawi. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(2):325–35.

Sibhatu KT, Krishna VV, Qaim M. Production diversity and dietary diversity in smallholder farm households. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(34):10657–62.

van der Lee J, Oosting S, Klerkx L, Opinya F, Bebe BO. Effects of proximity to markets on dairy farming intensity and market participation in Kenya and Ethiopia. Agric Syst. 2020;1(184):102891.

OECD. Increasing Productivity and Improving Market Access. In: Promoting Pro-Poor Growth [Internet]. OECD; 2007 [cited 2020 Sep 3]. p. 153–71. Available from: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/promoting-pro-poor-growth/increasing-productivity-and-improving-market-access_9789264024786-16-en.

Stifel D, Minten B. Market access, well-being, and nutrition: evidence from Ethiopia. World Dev. 2017;1(90):229–41.

Bach A, Gregor E, Sridhar S, Fekadu H, Fawzi W. Multisectoral integration of nutrition, health, and agriculture: implementation lessons from Ethiopia. Food Nutr Bull. 2020;41(2):275–92.

Pelletier DL, Frongillo EA, Gervais S, Hoey L, Menon P, Ngo T, et al. Nutrition agenda setting, policy formulation and implementation: lessons from the mainstreaming nutrition initiative. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27(1):19–31.

World Bank. Improving Nutrition Through Multisectoral Approaches [Internet]. Washington, D.C.; 2013 [cited 2020 Sep 24]. Available from: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/16450.

Ezezika OC, Deadman J, Murray J, Mabeya J, Daar AS. To trust or not to trust: a model for effectively governing public-private partnerships. Ag Bio Forum. 2013;16(1):21–36.

Ezezika OC, Mabeya J, Daar AS. Building effective partnerships: The role of trust in the Virus Resistant Cassava for Africa project. Agric Food Security. 2012;1(S1):S7. https://doi.org/10.1186/2048-7010-1-S1-S7.

Ezezika OC, Oh J. What is trust?: perspectives from farmers and other experts in the field of agriculture in Africa. Agric Food Security. 2012;1(1):S1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2048-7010-1-S1-S1.

Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock. Zambia National Agriculture Investment Plan (NAIP) 2014-2018 [Internet]. Lusaka, Zambia; 2013 [cited 2022 Aug 29]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Anoop-Srivastava/post/Zambia-agricultural-sector/attachment/59d655f979197b80779acf23/AS%3A527949026004992%401502884264277/download/6.+Zambia_investment+plan.pdf.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Justin Mabeya for comments on earlier drafts of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception: OE. Study design: RA and OE. Analysis and interpretation of data: RA and SMD. Draft of the manuscript: RA and SMD. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: RA, SMD and OE. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

An overview of the historical development of national agriculture and nutrition policies in sub-Saharan Africa

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Asirvatham, R., Demi, S.M. & Ezezika, O. Are sub-Saharan African national food and agriculture policies nutrition-sensitive? A case study of Ethiopia, Ghana, Malawi, Nigeria, and South Africa. Agric & Food Secur 11, 60 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-022-00398-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-022-00398-x