Abstract

Maintaining the physiological pH of interstitial fluid is crucial for normal cellular functions. In disease states, tissue acidosis is a common pathologic change causing abnormal activation of acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs), which according to cumulative evidence, significantly contributes to inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and other pathologic mechanisms (i.e., pain, stroke, and psychiatric conditions). Thus, it has become increasingly clear that ASICs are critical in the progression of neurologic diseases. This review is focused on the importance of ASICs as potential therapeutic targets in combating neurologic diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Under normal physiologic conditions, intra- and extracellular pH is maintained between 7.3-7.0. Increased neuronal excitability alters pH to activate various receptors and ion channels in cell membranes, including a variety of voltage-gated and ligand-gated ion channels [1, 2]. It has recently been shown that acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs) first cloned by Waldmann and colleagues [3] are activated in response to diminished extracellular pH [4]. However, the functional roles of ASICs in peripheral and central components of the nervous system remain unclear.

Neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease, are not curable at present. Although animal models of such conditions have been utilized to develop new therapeutic strategies, effective treatments have been elusive. Clinical trial and animal experimentation outcomes suggest that Ca2+ overload, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, energy metabolism, and acidosis are involved in neurodegenerative processes. Consequently, ASICs may be pivotal in the pathophysiology of these disorders.

Basic characteristics of ASICs

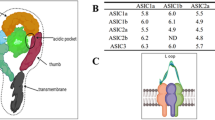

ASICs are ligand-gated cation channels activated by extracellular H+ and are widely distributed in mammalian central and peripheral nervous systems. As members of the degenerin and epithelial Na+ channel (DEG/ENaC) ion channel superfamily, displaying high Na+ permeability and sensitivity to amiloride blockade (with brief exposure), ASICs are composed of two hydrophobic transmembrane domains, short N- and C- termini, and a large extracellular loop (ECD) spanning the two hydrophobic domains [5–7]. The ECD harbors a so-called “acidic pocket” region that is responsible for acid-dependent gating, desensitization, and response to extracellular modulators [8]. This acidic pocket contains several pairs of acidic amino acids, is situated at the interface between two subunits, and is considered one of the ASIC pH sensors. Cations may gain access via lateral fenestrations in the wrist region and then move into a broad extracellular vestibule [8, 9]. The crystal structure of chicken ASIC1 incorporates a trimeric channel complex, marked by three radial subunits and a central ion pore [10]. Discovery of the ASIC crystal structure provided insight into inherent mechanisms of channel depolarization, inactivation, and modulation. The three-dimensional ECD consists of 12 b-sheets and 7 a-helices [9]. Two long a-helices form the transmembrane domains, which line the ion pore [9].

ASICs were first identified in the nervous system and cloned 14 years ago [11]. In mammals, there are six distinct ASIC subunits (ASIC1a, ASIC1b, ASIC2a, ASIC2b, ASIC3, and ASIC4) encoded by four different genes (ACCN1–4) (Table 1) [12]. These subunits form functional ion channels as dimers or heteropolymers, and differing channels vary in activation conditions, ion selectivity, kinetics, and distributions.

ASICs are activated by falls in extracellular pH, particularly tissue acidosis (Fig. 1). Whole-cell patch clamp recording studies show that an increase in intracellular Ca2+ due to cerebral ischemia may be attenuated by the nonspecific Na+ channel inhibitor amiloride or the specific ASIC1a inhibitor PcTx1, both of which prevent tissue damage (Fig. 2) [13]. Other studies indicate that ASIC1a-mediated Ca2+ overload contributes to ischemic nerve cell death and inflammation in multiple sclerosis, with PcTx1 protecting cells by reducing Ca2+ influx [14]. Thus, local tissue acidosis induced by cerebral ischemia results in part from intracellular Ca2+ influx triggered by ASIC activation [15]. Still another study maintains that limiting ASIC1a expression after infarction exerts a neuroprotective effect [12]. Evidence shows that ASICs are involved sensations of pain and taste [16].

ASICs are activated by extracellular protons (H+) and are primarily permeable to Na+ (Ca2+ to a lesser degree). ASIC activation depolarizes cell membranes, activating voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) to induce influx of Ca2+. Ca2+ influx contributes to calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) phosphorylation and may influence other second-messenger pathways. Amiloride, NSAIDs, and nafamostat are ASIC inhibitors

Localization and electrophysiologic characteristics of ASICs

In order to understand the physiologic functions of ASICs, determining their distributions and electrophysiologic characteristics is critical. ASIC1a, ASIC1b, ASIC2a, and ASIC3 activate and induce inward current at pH values of 6.2, 5.9, 4.4, and 6.5, respectively [17]. In retinal ganglia, a decline in synaptic cleft pH inhibits the opening of presynaptic membrane Ca2+ channels. Changes in synaptic cleft pH likely are important in activation of ASICs [18]. ASIC1a is expressed at synapses, primarily in conjunction with the postsynaptic membrane [19]. Knock out of ASIC1a inhibits pH 5.0-induced inward current in cultured neurons from hippocampus, amygdala, and cortex [20]. ASIC1a is also co-expressed with ASIC1b in sensory neurons [21]. The ASIC2b subunit, which by itself is nonfunctional, is chiefly expressed in neurons of outer peripheral and central nervous systems, whereas ASIC3 is largely expressed in dorsal root ganglia (DRG) [22]. Other researchers have demonstrated expression of ASIC3 in bone, muscle, and cardiac tissue and expression of ASIC4 in pituitary gland [21, 23].

Pharmacologic characteristics of ASICs

Amiloride, which is widely used clinically as a diuretic, inhibits Na+ channels in renal tubular epithelial cells and is a non-specific inhibitor of ASICs [11]. With an IC50 of ~10-50 μM, amiloride not only suppresses ASIC currents but also prevents upsurges of intracellular Ca2+ and plasma membrane depolarization induced by extracellular acidosis. Studies of the Na+ ion channel family indicate that amiloride directly blocks ASIC activation, thereby inhibiting current generated via acidic pH levels [24].

A-317567 is a small molecule (reportedly more selective than amiloride) and a nondiscriminatory inhibitor of ASIC currents in sensory and central neurons capable of blocking ASIC1a, ASIC2a, and ASIC3 currents [25]. Unlike amiloride, A-317567 provides significant relief from chronic pain induced by tissue acidification [25].

Latest studies also suggest that non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) help relieve pain by modulating ASIC activity [26]. NSAIDs directly inhibit inflammation-related sensory neuronal increases in expression and activity of ASIC1a and ASIC3, thus conferring their analgesic effect [27, 28].

Tarantula toxin 1 (psalmotoxin, PcTx1) is another selective inhibitor of ASIC1a [29]. In a heterologous expression system, PcTx1 inhibits ASIC1a-induced current (IC50 ~ 1 nM), with no inhibitory effect on currents induced by voltage-gated ion channels, including some K+, Na+, and Ca2+ channels, and ligand-gated channels [30]. At this concentration, PcTx1 changes the affinity of ASIC1a for H+ ions, transforming the channels from resting to inactivated states and increasing their closing times [30, 31].

APETx2 is a selective inhibitor of ASIC3 [32]. Declining extracellular pH triggers a biphasic ASIC3 response: fast depolarization followed by a prolonged refractory period. APETx2 inhibits several subunits (i.e., 1a, 1b, 2b) of ASIC3 but does not affect ASIC1a, ASIC1b, ASIC2a, or ASIC3/2a [33]. APETx2 inhibits ASIC3-generated and sustained window currents evoked at pH 7.0 [34].

The Texas coral snake toxin known as MitTx activates ASIC1a and ASIC1b homomers and enhances pH sensitivity of ASIC2a channels [35]. MitTx has weak effects on ASIC2a if applied at pH 7.4 but potentiates acid-evoked current by shifting the activation curve towards less acidity. The effect of MitTx on ASIC-mediated neuronal currents in trigeminal ganglia of mice is a function of ASIC1a channels and is abolished in ASIC1a-knockout mice [36].

Another agent, 2-guanidine-4-methylquinazoline (GMQ), acts to persistently activate ASIC3 at normal pH [37]. Injection of GMQ into a mouse paw activates ASIC3, triggering pain behavior in wild-type but not in ASIC3-knockout mice. Although the potency of GMQ in activating ASIC3 is low (EC50 ~ 1 mM) at physiologic Ca2+ concentrations, GMQ may influence pH dependencies of other ASIC subtypes, preempting current at physiologic pH by a shift to more acidic pH [2].

PhcrTx1 is a compound extracted from the sea anemone (Phymanthus crucifer) that inhibits peak neuronal ASIC currents in rat DRG [38].

Endogenous compounds that are active in this setting include spermine, which intensifies ASIC1a activation and aggravates ischemic neuronal injury [39], and agmatine, which activates homomeric ASIC3 and heteromeric ASIC3-ASIC1b [37, 40]. Mambalgin-1, a peptide isolate of snake venom, selectively inhibits currents mediated by ASIC1and ASIC1b homomers and heteromers [41]. The potent protease inhibitor, nafamostat, is used to treat acute pancreatitis [42]. It also inhibits ASIC1a and ASIC2a and blocks initial-phase transient currents of ASIC3 [43].

ASICs as potential therapeutic targets for treating neurologic diseases

The various functions of ASICs in the nervous system have yet to be fully understood. ASICs are widely distributed throughout all regions of the brain where they participate in synaptic plasticity, learning, and sensory transduction. In particular, ASIC1a is a known purveyor of synaptic plasticity, especially the facilitation of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor activation in long-term potentiation (LTP) of hippocampus [44]. However, a recent study by the Lien group showed that disruption of the ASIC1a gene did not impair normal hippocampal LTP and spatial memory in ASIC1a conditional knockout mice [45]. Still, Wemmie et al. recently detected local pH changes during normal brain activity in mouse and human brains, underscoring the potential for ASIC activation in this context [46]. More studies are clearly needed to delineate the roles of ASIC1 in the nervous system (Table 2).

Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a disabling disease characterized by selective, gradual apoptosis of midbrain dopaminergic (DA) neurons and progressive motor deterioration. Increasing efforts have been made to identify putative causes of PD, namely oxidative stress, microglial inflammation, and mitochondrial dysfunction. Interestingly, these processes often result in tissue acidification; and lactic acidosis, which further aggravates neuronal damage, has been documented in the brains of patients with PD and in the classic 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-induced animal model of PD [47, 48]. A recently conducted study has demonstrated that mitochondrial ASIC1a may serve as an important regulator of MPT pores, thus contributing to oxidative neuronal cell death [49]. Moreover, Arias and colleagues have found that MPTP-treated mice develop brain tissue acidosis and that ASIC inhibitors amiloride and PcTx-1 protect against substantia nigra neuronal degeneration by reducing levels of DA and its transporter and preventing apoptosis [50]. In addition, mutation of the parkin gene or a lack of endogenous parkin protein results in abnormal ASIC currents, protein degradation, and DA neuronal injury, suggesting that ASIC currents may mediate the fundamental pathology in PD [51]. ASIC inhibitors amiloride and PcTx-1 are also protective of substantia nigra in the mouse PD model, preventing neuronal loss and apoptosis [50]. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation likewise increases levels of ASIC1 and ASIC2a expression in rat microglia and induces inflammatory cytokines [52]. Such findings collectively indicate that modulating microglial ASIC function may control neurodegenerative diseases such as PD.

Huntington’s disease

In individuals with Huntington’s disease (HD), CAG repeats of the huntingtin gene IT15 (copy number >35–40) produce variations in the huntingtin protein, leading to duplicated glutamine residues. The proteins gradually form large aggregates in the brain, leading to disrupted neuronal function and neuronal death. As yet, there is no effective treatment. However, Wong et al. have reported that ASIC1 inhibition enhances ubiquitin-proteasome system activity and reduces huntingtin-polyglutamine accumulation, implicating ASICs in the pathogenesis of HD as well [53].

Pain

Tissue acidosis often increases pain sensitivity. Release of H+ ions in damaged tissue lowers the pH locally, promoting pain receptor depolarization and generating pain [14]. Somatic pain originating in the peripheral nervous system is attributable to ASIC3 [54]. This not only pertains to primary afferent gastrointestinal visceral pain but also applies to chemical nociception of the upper gastrointestinal system and to mechanical nociception of the colon [55]. Hence, ASIC3 inhibition may be a means of relieving chronic abdominal pain [56]. Analgesia may similarly be achieved by blocking neuronal ASIC1a expression in DRG, so it appears that ASIC1a activation is also a factor in sensitization of the peripheral nervous system and generation of pain [56]. A-317567, an inhibitor of ASIC1/3, alleviates skin pain in mice after surgery [56]. Additionally, NSAIDs may inhibit ASIC expression in sensory neurons, block Ca2+ channels, and reduce peak ASIC currents [28, 57]. Expression levels of ASIC1a and ASIC2a are upregulated in the spinal cord, presumably to effect central pain sensitization [58, 59]. Genetic disruption of ASIC1a alleviates mechanical hyperalgesia elicited by intrathecal brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) injections [60], and intrathecal administration of PcTx-1 mitigates pain behavior in rodents [61]. These studies provide compelling evidence that inhibition of ASICs may ease pain.

Cerebral ischemia

Severe cerebral ischemia may lower brain pH to 6.3 or less, resulting in Ca2+ overload and neuronal cytotoxicity. ASIC1a and ASIC2a are widely expressed in the central nervous system [56]. Because ASIC1a is selectively permeable to Ca2+, activation of ASIC1a-bearing channels promotes Ca2+ influx [4]. Activation of ASIC1a may trigger membrane depolarization, spurring Ca2+ influx directly via ASIC1a homomers or ASIC1a/2b heteromers, voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, and NMDA receptors [62]. Intracellular Ca2+ overload then evokes a sequence of cytotoxic events that ultimately aggravate tissue and cell damage through intracellular enzyme activation. Cytotoxicity due to acidic metabolites and intracellular Ca2+ overload causes protein, lipid, and nucleic acid degradation, with apoptosis and necrosis as eventual endpoints. Zhang et al. found that ischemia has no effect on neuronal ASIC1 expression in the hypothalamus but ASIC2 expression and expression of anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-W were upregulated [63], so perhaps ASIC2 takes part in preventing apoptosis induced by cerebral ischemia [63]. Nevertheless, other studies do show that ASIC1a blockade confers neuroprotective effects in a middle cerebral artery occlusion model [39, 64]. Thus, the functional roles of ASICs may vary in differing pathologic states, rendering them a new therapeutic target in ischemic brain injury.

Migraine

Migraine is typically a severe unilateral or bilateral pulsatile headache. Studies indicate that ASICs have major roles in activating pain-sensitive afferent nerves during migraines [65, 66], including dural branches [66]. Dural ischemia or release of macrophage granular contents may cause local inflammatory changes, lowering tissue pH locally and in turn activating ASICs and dural primary afferent nerves [67]. Neuronal ASIC3 expression is found in most trigeminal ganglia (TG) and dural afferents [68]. Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) release, resulting in neurogenic inflammation and headache progression, is increased in TG neurons via ASIC3 activation [68]. In a preclinical study, amiloride was found to block cortical spreading depression (CSD) and inhibit TG activation, implying that an ASIC1-dependent mechanism is operant [69]. ASIC signaling cascades then seem to be critical in development of migraine, despite the need for greater clarity at present.

Multiple sclerosis

ASIC1a is upregulated in oligodendrocytes and in axons of an acute autoimmune encephalomyelitis mouse model, as well as in brain tissue from patients with multiple sclerosis, and this increased expression is associated with axonal injury [70]. On the other hand, genetic disruption of ASIC1 alleviates this axonal degeneration and reduces clinical deficits [71]. In addition, amiloride attenuates myelin and neuronal damage in multiple sclerosis [72]. Blockade of ASIC1a expression may therefore confer neuroprotective effects in patients with multiple sclerosis.

Seizure

During seizure activity, intense neuronal firing causes a drop in brain pH, raising the possibility that abnormal activation of ASICs affect onset and maintenance of epileptic seizures. The frequency of tonic-clonic seizures is increased by intraventricular injection of the ASIC1a inhibitor PcTX-1 [73]. However, EEG tracings confirm that ASIC1a overexpression does not affect seizure onset and may prematurely terminate episodes [74]. As opposed to ASIC1a-knockout mice, wild-type mice show declines in magnitude and intensity of seizures, indicating that a drop in pH and augmented ASIC1a expression both signal antiepileptic outcomes [75]. Furthermore, low-pH interneuronal and excitatory pyramidal cell stimulation increases ASIC1a inhibitory neuronal currents, suggesting that ASIC1a may limit seizures by dampering neuronal excitability [75].

Malignant glioma

ASIC1a is widely expressed in malignant glial cells. Amiloride- and PcTx1-sensitive cation currents have been recorded in human glioblastoma [76], and PcTx1 or ASIC1a knock-down inhibits cell migration and cell-cycle progression in gliomas [77, 78]. ASIC1a inhibition leads to cell-cycle arrest through upregulation of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor protein expression and blockade of growth factor phosphorylation cascades [77, 78]. The amiloride analogue, benzamil, also produces cell-cycle arrest in glioblastoma [77]. This body of evidence clearly links ASIC1a activation with cellular growth and migration in malignant gliomas.

Conclusion

In this review, expression, localization, and mechanisms (biochemical, physiologic, and pathophysiologic) of ASICs are discussed. Based on a substantial body of research, largely derived from animal models, their involvement in various neurologic diseases seems certain. It is therefore important to determine how this knowledge translates to humans, given that ASIC-blocking drugs have may have therapeutic potential in a spectrum of neurologic and psychiatric disorders. Better understanding of related molecular mechanisms and signaling pathways will help clarify the role of ASICs going forward.

References

Wemmie JA, Taugher RJ, Kreple CJ. Acid-sensing ion channels in pain and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14(7):461–71.

Xiong ZG, Pignataro G, Li M, Chang SY, Simon RP. Acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs) as pharmacological targets for neurodegenerative diseases. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8(1):25–32.

Wemmie JA, Price MP, Welsh MJ. Acid-sensing ion channels: advances, questions and therapeutic opportunities. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29(10):578–86.

Benarroch EE. Acid-sensing cation channels: structure, function, and pathophysiologic implications. Neurology. 2014;82(7):628–35.

Sherwood TW, Frey EN, Askwith CC. Structure and activity of the acid-sensing ion channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;303(7):C699–710.

Chu XP, Papasian CJ, Wang JQ, Xiong ZG. Modulation of acid-sensing ion channels: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol. 2011;3(4):288–309.

Grunder S, Chen X. Structure, function, and pharmacology of acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs): focus on ASIC1a. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol. 2010;2(2):73–94.

Gonzales EB, Kawate T, Gouaux E. Pore architecture and ion sites in acid-sensing ion channels and P2X receptors. Nature. 2009;460(7255):599–604.

Jasti J, Furukawa H, Gonzales EB, Gouaux E. Structure of acid-sensing ion channel 1 at 1.9 A resolution and low pH. Nature. 2007;449(7160):316–23.

Grunder S, Pusch M. Biophysical properties of acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs). Neuropharmacology. 2015;S0028–3908(14):00467–5.

Waldmann R, Champigny G, Bassilana F, Heurteaux C, Lazdunski M. A proton-gated cation channel involved in acid-sensing. Nature. 1997;386(6621):173–7.

Qadri YJ, Rooj AK, Fuller CM. ENaCs and ASICs as therapeutic targets. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;302(7):C943–65.

Mari Y, Katnik C, Cuevas J. ASIC1a channels are activated by endogenous protons during ischemia and contribute to synergistic potentiation of intracellular Ca(2+) overload during ischemia and acidosis. Cell Calcium. 2010;48(1):70–82.

Kellenberger S, Schild L. International union of basic and clinical pharmacology. XCI. Structure, function, and pharmacology of acid-sensing Ion channels and the epithelial Na + channel. Pharmacol Rev. 2015;67(1):1–35.

Li M, Inoue K, Branigan D, Kratzer E, Hansen JC, Chen JW, et al. Acid-sensing ion channels in acidosis-induced injury of human brain neurons. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30(6):1247–60.

Chu XP, Xiong ZG. Acid-sensing ion channels in pathological conditions. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;961:419–31.

Gautam M, Benson CJ, Ranier JD, Light AR, Sluka KA. ASICs do not play a role in maintaining hyperalgesia induced by repeated intramuscular acid injections. Pain Res Treat. 2012;2012:817347.

Arnett TR. Extracellular pH regulates bone cell function. J Nutr. 2008;138(2):415S–8.

Kreple CJ, Lu Y, Taugher RJ, Schwager-Gutman AL, Du J, Stump M, et al. Acid-sensing ion channels contribute to synaptic transmission and inhibit cocaine-evoked plasticity. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(8):1083–91.

Xiong Z, Liu Y, Hu L, Ma B, Ai Y, Xiong C. A rapid facilitation of acid-sensing ion channels current by corticosterone in cultured hippocampal neurons. Neurochem Res. 2013;38(7):1446–53.

Gautam M, Benson CJ. Acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs) in mouse skeletal muscle afferents are heteromers composed of ASIC1a, ASIC2, and ASIC3 subunits. FASEB J. 2013;27(2):793–802.

Sluka KA, Rasmussen LA, Edgar MM, O’Donnell JM, Walder RY, Kolker SJ, et al. Acid-sensing ion channel 3 deficiency increases inflammation but decreases pain behavior in murine arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(5):1194–202.

Donier E, Rugiero F, Jacob C, Wood JN. Regulation of ASIC activity by ASIC4–new insights into ASIC channel function revealed by a yeast two-hybrid assay. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28(1):74–86.

Behan AT, Breen B, Hogg M, Woods I, Coughlan K, Mitchem M, et al. Acidotoxicity and acid-sensing ion channels contribute to motoneuron degeneration. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20(4):589–98.

Liu X, He L, Dinger B, Fidone SJ. Chronic hypoxia-induced acid-sensitive ion channel expression in chemoafferent neurons contributes to chemoreceptor hypersensitivity. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301(6):L985–92.

Dorofeeva NA, Barygin OI, Staruschenko A, Bolshakov KV, Magazanik LG. Mechanisms of non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs action on ASICs expressed in hippocampal interneurons. J Neurochem. 2008;106(1):429–41.

Voilley N, de Weille J, Mamet J, Lazdunski M. Nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs inhibit both the activity and the inflammation-induced expression of acid-sensing ion channels in nociceptors. J Neurosci. 2001;21(20):8026–33.

Voilley N. Acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs): new targets for the analgesic effects of non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 2004;3(1):71–9.

Escoubas P, Bernard C, Lambeau G, Lazdunski M, Darbon H. Recombinant production and solution structure of PcTx1, the specific peptide inhibitor of ASIC1a proton-gated cation channels. Protein Sci. 2003;12(7):1332–43.

Salinas M, Rash LD, Baron A, Lambeau G, Escoubas P, Lazdunski M. The receptor site of the spider toxin PcTx1 on the proton-gated cation channel ASIC1a. J Physiol. 2006;570(Pt 2):339–54.

Qadri YJ, Berdiev BK, Song Y, Lippton HL, Fuller CM, Benos DJ. Psalmotoxin-1 docking to human acid-sensing ion channel-1. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(26):17625–33.

Delaunay A, Gasull X, Salinas M, Noël J, Friend V, Lingueglia E, et al. Human ASIC3 channel dynamically adapts its activity to sense the extracellular pH in both acidic and alkaline directions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(32):13124–9.

Anangi R, Rash LD, Mobli M, King GF. Functional expression in Escherichia coli of the disulfide-rich sea anemone peptide APETx2, a potent blocker of acid-sensing ion channel 3. Mar Drugs. 2012;10(7):1605–18.

Deval E, Noel J, Gasull X, Delaunay A, Alloui A, Friend V, et al. Acid-sensing ion channels in postoperative pain. J Neurosci. 2011;31(16):6059–66.

Bohlen CJ, Chesler AT, Sharif-Naeini R, Medzihradszky KF, Zhou S, King D, et al. A heteromeric Texas coral snake toxin targets acid-sensing ion channels to produce pain. Nature. 2011;479(7373):410–4.

Baron A, Diochot S, Salinas M, Deval E, Noël J, Lingueglia E. Venom toxins in the exploration of molecular, physiological and pathophysiological functions of acid-sensing ion channels. Toxicon. 2013;75:187–204.

Yu Y, Chen Z, Li WG, Cao H, Feng EG, Yu F, et al. A nonproton ligand sensor in the acid-sensing ion channel. Neuron. 2010;68(1):61–72.

Rodriguez AA, Salceda E, Garateix AG, Zaharenko AJ, Peigneur S, López O, et al. A novel sea anemone peptide that inhibits acid-sensing ion channels. Peptides. 2014;53:3–12.

Duan B, Wang YZ, Yang T, Chu XP, Yu Y, Huang Y, et al. Extracellular spermine exacerbates ischemic neuronal injury through sensitization of ASIC1a channels to extracellular acidosis. J Neurosci. 2011;31(6):2101–12.

Li WG, Yu Y, Zhang ZD, Cao H, Xu TL. ASIC3 channels integrate agmatine and multiple inflammatory signals through the nonproton ligand sensing domain. Mol Pain. 2010;6:88.

Diochot S, Baron A, Salinas M, Douguet D, Scarzello S, Dabert-Gay AS, et al. Black mamba venom peptides target acid-sensing ion channels to abolish pain. Nature. 2012;490(7421):552–5.

Muto S, Imai M, Asano Y. Effect of nafamostat mesilate on Na + and K+ transport properties in the rabbit cortical collecting duct. Br J Pharmacol. 1993;109(3):673–8.

Ugawa S, Ishida Y, Ueda T, Inoue K, Nagao M, Shimada S. Nafamostat mesilate reversibly blocks acid-sensing ion channel currents. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;363(1):203–8.

Zha XM. Acid-sensing ion channels: trafficking and synaptic function. Mol Brain. 2013;6:1.

Wu PY, Huang YY, Chen CC, Hsu TT, Lin YC, Weng JY, et al. Acid-sensing ion channel-1a is not required for normal hippocampal LTP and spatial memory. J Neurosci. 2013;33(5):1828–32.

Magnotta VA, Heo HY, Dlouhy BJ, Dahdaleh NS, Follmer RL, Thedens DR, et al. Detecting activity-evoked pH changes in human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(21):8270–3.

Chu XP, Miesch J, Johnson M, Root L, Zhu XM, Chen D, et al. Proton-gated channels in PC12 cells. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87(5):2555–61.

Wang YZ, Xu TL. Acidosis, acid-sensing ion channels, and neuronal cell death. Mol Neurobiol. 2011;44(3):350–8.

Wang YZ, Zeng WZ, Xiao X, Huang Y, Song XL, Yu Z, et al. Intracellular ASIC1a regulates mitochondrial permeability transition-dependent neuronal death. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20(10):1359–69.

Arias RL, Sung ML, Vasylyev D, Zhang MY, Albinson K, Kubek K, et al. Amiloride is neuroprotective in an MPTP model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;31(3):334–41.

Joch M, Ase AR, Chen CX, MacDonald PA, Kontogiannea M, Corera AT, et al. Parkin-mediated monoubiquitination of the PDZ protein PICK1 regulates the activity of acid-sensing ion channels. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(8):3105–18.

Yu XW, Hu ZL, Ni M, Fang P, Zhang PW, Shu Q, et al. Acid-sensing ion channels promote the inflammation and migration of cultured rat microglia. Glia. 2014;63(3):483–96.

Wong HK, Bauer PO, Kurosawa M, Goswami A, Washizu C, Machida Y, et al. Blocking acid-sensing ion channel 1 alleviates Huntington’s disease pathology via an ubiquitin-proteasome system-dependent mechanism. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(20):3223–35.

Jensen JE, Cristofori-Armstrong B, Anangi R, Anangi R, Rosengren KJ, Lau CH, et al. Understanding the molecular basis of toxin promiscuity: the analgesic sea anemone peptide APETx2 interacts with acid-sensing ion channel 3 and hERG channels via overlapping pharmacophores. J Med Chem. 2014;57(21):9195–203.

Page AJ, Brierley SM, Martin CM, Price MP, Symonds E, Butler R, et al. Different contributions of ASIC channels 1a, 2, and 3 in gastrointestinal mechanosensory function. Gut. 2005;54(10):1408–15.

Lingueglia E. Acid-Sensing Ion Channels (ASICs) in pain. Biol Aujourdhui. 2014;208(1):13–20.

Mishra V, Verma R, Raghubir R. Neuroprotective effect of flurbiprofen in focal cerebral ischemia: the possible role of ASIC1a. Neuropharmacology. 2010;59(7–8):582–8.

Duan B, Wu LJ, Yu YQ, Ding Y, Jing L, Xu L, et al. Upregulation of acid-sensing ion channel ASIC1a in spinal dorsal horn neurons contributes to inflammatory pain hypersensitivity. J Neurosci. 2007;27(41):11139–48.

Wu LJ, Duan B, Mei YD, Gao J, Chen JG, Zhuo M, et al. Characterization of acid-sensing ion channels in dorsal horn neurons of rat spinal cord. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(42):43716–24.

Duan B, Liu DS, Huang Y, Zeng WZ, Wang X, Yu H, et al. PI3-kinase/Akt pathway-regulated membrane insertion of acid-sensing ion channel 1a underlies BDNF-induced pain hypersensitivity. J Neurosci. 2012;32(18):6351–63.

Dawson RJ, Benz J, Stohler P, Tetaz T, Joseph C, Huber S, et al. Structure of the acid-sensing ion channel 1 in complex with the gating modifier Psalmotoxin 1. Nat Commun. 2012;3:936.

Gao J, Duan B, Wang DG, Deng XH, Zhang GY, Xu L, et al. Coupling between NMDA receptor and acid-sensing ion channel contributes to ischemic neuronal death. Neuron. 2005;48(4):635–46.

Zhang Y, Zhou L, Zhang X, Bai J, Shi M, Zhao G. Ginsenoside-Rd attenuates TRPM7 and ASIC1a but promotes ASIC2a expression in rats after focal cerebral ischemia. Neurol Sci. 2012;33(5):1125–31.

Gu L, Yang Y, Sun Y, Zheng X. Puerarin inhibits acid-sensing ion channels and protects against neuron death induced by acidosis. Planta Med. 2010;76(6):583–8.

Yan J, Dussor G. Ion channels and migraine. Headache. 2014;54(4):619–39.

Dussor G. ASICs as therapeutic targets for migraine. Neuropharmacology. 2015;S0028–3908(14):00466–3.

Tso AR, Goadsby PJ. New targets for migraine therapy. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2014;16(11):318.

Durham PL, Masterson CG. Two mechanisms involved in trigeminal CGRP release: implications for migraine treatment. Headache. 2013;53(1):67–80.

Holland PR, Akerman S, Andreou AP, Karsan N, Wemmie JA, Goadsby PJ. Acid-sensing ion channel 1: a novel therapeutic target for migraine with aura. Ann Neurol. 2012;72(4):559–63.

Vergo S, Craner MJ, Etzensperger R, Attfield K, Friese MA, Newcombe J, et al. Acid-sensing ion channel 1 is involved in both axonal injury and demyelination in multiple sclerosis and its animal model. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 2):571–84.

Friese MA, Craner MJ, Etzensperger R, Vergo S, Wemmie JA, Welsh MJ, et al. Acid-sensing ion channel-1 contributes to axonal degeneration in autoimmune inflammation of the central nervous system. Nat Med. 2007;13(12):1483–9.

Arun T, Tomassini V, Sbardella E, de Ruiter MB, Matthews L, Leite MI, et al. Targeting ASIC1 in primary progressive multiple sclerosis: evidence of neuroprotection with amiloride. Brain. 2013;136(Pt 1):106–15.

McKhann 2nd GM. Seizure termination by acidosis depends on ASIC1a. Neurosurgery. 2008;63(4):N10.

N’Gouemo P. Amiloride delays the onset of pilocarpine-induced seizures in rats. Brain Res. 2008;1222:230–2.

Ziemann AE, Schnizler MK, Albert GW, Severson MA, Howard III MA, Welsh MJ, et al. Seizure termination by acidosis depends on ASIC1a. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11(7):816–22.

Berdiev BK, Xia J, McLean LA, Markert JM, Gillespie GY, Mapstone TB, et al. Acid-sensing ion channels in malignant gliomas. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(17):15023–34.

Rooj AK, McNicholas CM, Bartoszewski R, Bebok Z, Benos DJ, Fuller CM. Glioma-specific cation conductance regulates migration and cell cycle progression. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(6):4053–65.

Kapoor N, Bartoszewski R, Qadri YJ, Bebok Z, Bubien JK, Fuller CM, et al. Knockdown of ASIC1 and epithelial sodium channel subunits inhibits glioblastoma whole cell current and cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(36):24526–41.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81471299, 81301090), Jiangsu Provincial Special Program of Medical Science (BL2014042), the Plans for Graduate Research and Innovation in Colleges and Universities of Jiangsu Province (CXZZ13_0833), Suzhou Clinical Key Disease Diagnosis and Treatment Technology Foundation (LCZX201304), and Suzhou Medical Key Discipline Project. The Priority Academic Program Development (PAPD) of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions also contributed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SL drafted and C-FL critically revised the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, S., Cheng, XY., Wang, F. et al. Acid-sensing ion channels: potential therapeutic targets for neurologic diseases. Transl Neurodegener 4, 10 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40035-015-0031-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40035-015-0031-3