Abstract

Purpose

This current study attempted to investigate whether one-stitch method (OM) of temporary ileostomy influenced the stoma-related complications after laparoscopic low anterior resection (LLAR).

Methods

We searched for eligible studies in four databases including PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and CNKI from inception to July 20, 2023. Both surgical outcomes and stoma-related complications were compared between the OM group and the traditional method (TM) group. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) was adopted for quality assessment. RevMan 5.4 was conducted for data analyzing.

Results

Totally 590 patients from six studies were enrolled in this study (272 patients in the OM group and 318 patients in the TM group). No significant difference was found in baseline information (P > 0.05). Patients in the OM group had shorter operative time in both the primary LLAR surgery (MD = − 17.73, 95%CI = − 25.65 to − 9.80, P < 0.01) and the stoma reversal surgery (MD = − 18.70, 95%CI = − 22.48 to −14.92, P < 0.01) than patients in the TM group. There was no significant difference in intraoperative blood loss of the primary LLAR surgery (MD = − 2.92, 95%CI = − 7.15 to 1.32, P = 0.18). Moreover, patients in the OM group had fewer stoma-related complications than patients in the TM group (OR = 0.55, 95%CI = 0.38 to 0.79, P < 0.01).

Conclusion

The OM group had shorter operation time in both the primary LLAR surgery and the stoma reversal surgery than the TM group. Moreover, the OM group had less stoma-related complications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Laparoscopic low anterior resection (LLAR) was one of the main treatment options for low rectal cancer patients [1, 2]. Compared with open surgery, LLAR had advantages of small incision and rapid recovery [3, 4]. However, some postoperative complications including anterior resection syndrome (ARS) and anastomotic leakage et al., influenced the patients’ quality of life and the following treatment [5,6,7].

Loop ileostomy, which was a measure for stool diversion, could reduce the pressure on the anastomosis [8, 9]. Previous studies demonstrated that temporary ileostomy could decrease the incidence of anastomotic leakage [10,11,12]. On the other hand, stoma-related complications including stoma bleeding, stoma stricture, stoma prolapse, stoma retraction, parastomal hernia and mucocutaneous separation were commonly existed [13, 14].

The traditional method (TM) of ileostomy was performed by suturing the peritoneum, anterior sheath, and skin layer, respectively [15]. This operation way needed numbers of sutures and was relatively difficult in obesity patients [16]. Meanwhile, the one-stitch method (OM), which was performed by using only one stitch to finish the ileostomy, was reported in some previous studies [16,17,18,19,20,21].

There were some studies focusing on the association between the ileostomy method and stoma-related complications. Some studies demonstrated that the OM group had less stoma-related complications than the TM group [20, 21]. However, other studies reported a different opinion [16,17,18,19]. Therefore, the purpose of this current study was to explore whether OM of temporary ileostomy affected the stoma-related complications after patients underwent LLAR.

Materials and methods

This study was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA) statement [22].

Search strategy

The PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and CNKI databases were searched from inception to July 20, 2023 by two authors, independently. The search strategy included three keywords: LLAR, ileostomy, and OM. The search strategy for LLAR was as follows: “laparoscopic low anterior resection” OR “laparoscopic anterior resection” OR “low anterior resection” OR “anterior resection”. In terms of ileostomy, we used “ileostomy” OR “loop ileostomy” OR “protective ileostomy” OR “protective loop ileostomy” OR “temporary ileostomy” OR “temporary loop ileostomy”. As for OM, we used “one-stitch” OR “one-stitch method” OR “method” to expand the search scope. The three main items were combined with “AND”. The search scope was limited to “the Title and Abstract”, and the search language was restricted to English and Chinese.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1, patients who underwent LLAR plus temporary ileostomy; 2, studies that divided the patients into the OM group and the TM group; 3, studies comparing the stoma-related complications between the two groups. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1, studies with incomplete data; 2, case reports, case series, letters to the editor, comments, conferences, and reviews.

Study selection

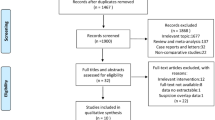

The selection procedure was, respectively, performed by two authors according to the search strategy. First, duplicated studies were removed. Then, the titles and abstracts were scanned to find eligible studies. Finally, full texts were checked for final analysis. Disagreement was settled by the third author.

Data collection

Baseline characteristics of the included studies were collected as follows: first author, year of publication, country of study, study date, sample size, and study type. Patients’ information included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), neoadjuvant therapy, distance from the anal verge, and tumor node metastasis (TNM) stage. The surgical information included the primary operation time, the stoma closure operation time, blood loss of primary surgery, and stoma-related complications. All the data were independently extracted by two authors, and information would be checked carefully to ensure the accuracy.

Quality assessment

The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) was conducted to assess the quality of included studies [23]. Studies scored nine points represented high quality; seven to eight points were considered of middle quality; and less than seven points meant low quality.

Surgical procedure of OM

The OM of ileostomy was performed while the LLAR procedure finished. A 2/0 absorbable suture was used to sew into the anterior sheath and peritoneum layer from the midpoint of one side of the skin. Then, the stitch would traverse the mesenteric mesangial avascular area and sew out the peritoneum and anterior sheath layer from the opposite skin. We used the same one stitch to traverse the avascular area again to finish knotting and fixing. Finally, 3/0 absorbable sutures were used to suture the skin layer with bowl, intermittently.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were calculated by the mean differences (MDs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs were calculated for dichotomous variables. The I2 value and the Chi-squared test were used to evaluate the heterogeneity of identified research [24, 25]. I2 > 50% meant high heterogeneity, the random effects model was adopted, and P < 0.1 was considered statistical difference. The fixed effects model was used when I2 < 50%, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The funnel plot was conducted to evaluate the publication bias. All the data analysis was performed using RevMan 5.4 (The Cochrane Collaboration, London, United Kingdom).

Results

Study selection

There were 483 studies identified according to the search strategy (97 studies in PubMed, 269 studies in Embase, 106 studies in the Cochrane Library, and 11 studies in CNKI). 184 duplicated studies were removed, and 299 studies were left. After titles and abstracts scanning, and full texts reading, six studies were enrolled for final analysis. No more eligible studies were found by reviewing the reference of the included six studies. The flowchart of study selection is shown in Fig. 1.

Baseline information of included studies

A total of six studies including 590 patients were enrolled for final analysis. The publishing dates were from 2020 to 2023, and the study period were from 2015 to 2022. All the studies were from China and were retrospective studies. Other details and NOS score are shown in Table 1.

Summary of characteristics between the OM group and the TM group

The baseline characteristics including age, sex, BMI, T2DM, neoadjuvant therapy, distance from the anal verge, and TNM stage were compared between the OM group and the TM group. No obvious significant difference was found in baseline characteristics (P > 0.05) (Table 2).

Surgical outcomes and stoma-related complications

The primary operation time, the second stoma closure operation time, blood loss of the primary surgery, and stoma-related complications were compared between the OM group and the TM group. After pooling analysis, we found that patients in the OM Group had a shorter operative time in the primary rectal cancer surgery (MD = − 17.73, 95%CI = − 25.65 to − 9.80, P < 0.01) (Fig. 2a). Patients in the OM group also had shorter operative time in stoma reversal surgery than patients in the TM group (MD = − 18.70, 95%CI = − 22.48 to − 14.92, P < 0.01) (Fig. 2b). There was no statistical difference in the blood loss of the primary surgery (MD = − 2.92, 95%CI = − 7.15 to 1.32, P = 0.18) (Fig. 2c). Moreover, patients in the OM group had fewer stoma-related complications than patients in the TM group (OR = 0.55, 95%CI = 0.38 to 0.79, P < 0.01) (Fig. 3).

Sensitivity and publication bias

Repeated meta-analysis was performed by excluding each study at one time, and no significant difference was found in each outcome. To evaluate the publication bias, the funnel plot was conducted, and no obvious bias was found (Fig. 4).

Discussion

This current study included 590 patients from six studies. After pooling analysis, we found that patients in the OM Group had a shorter operative time in both the primary rectal cancer surgery and in the stoma reversal surgery. Moreover, patients in the OM group had fewer stoma-related complications than patients in the TM group.

Temporary ileostomy, as a measure for stool diversion, could prevent the reoperation, because bowel contents will not contaminate the peritoneal cavity and result in septic shock [26, 27]. The average interval time to stoma closure was three to four months [28, 29]. Although the temporary ileostomy surgery was safe for patients after LLAR [30], the stoma-related complications and stoma reversal-related complications influenced the patients’ quality of life [31, 32]. The TM of ileostomy was performed by intermittently suturing the peritoneum, anterior sheath and skin layer, respectively [33]. This surgical method was time-spending, stitch-needing, and relatively difficult in such obese patients [16, 34, 35]. Studies had shown that the OM of ileostomy, which only needed one stitch to finish the surgery procedure, could reduce the operation time and save the sutures [17, 18]. The primary LLAR operation time and the ileostomy operation time were reduced due to the simplification of the ostomy procedure. As for the reduction in the time of the second stoma reversal operation, one of the reasons might be that the OM could reduce the degree of tissue adhesion around the stoma. However, whether the OM affected the stoma-related complications, there existed an argument.

Wang CJ et al [21] and Zhang L et al [20] reported that the overall incidence of stoma-related complications in the OM group was lower than in the TM group. In addition, other four studies thought there were no difference between the two groups when considering overall stoma-related complications [16,17,18,19]. Interestingly, Li XM et al. demonstrated that the OM group had lower incidence of skin irritation [18]. Moreover, Pei WT et al [16] conducted a subgroup analysis in BMI obese group and non-group, and they found that no obvious difference was detected in stoma-related complications either. The mechanism of stoma-related complications was unclear yet.

The stoma-related complications included early complications and delayed complications [36]. The early stoma-related complications included stoma retraction, stoma necrosis, stoma skin irritation and mucocutaneous separation, stoma edema, stoma bleeding, and stoma infection [37, 38]. The delayed complications included stoma stricture, stoma prolapse, and parastomal hernia [39]. Compared with the TM, on the one hand, the OM could string the peritoneum and anterior sheath layer [40]. On the other hand, the TM was particularly difficult due to thick abdominal fat and mesangial contracture in obese people, and the suture of peritoneum and anterior sheath was not satisfactory. Different from the TM, the OM effectively sidestepped this physiological difference. Therefore, the early stoma-related complications would be less in the OM group. However, the internal stability in OM was relatively poorer than TM. When the interval time to stoma reversal increased, the incidence of delayed complications would increase in the OM group. That was also the reason why the OM did not fit with colostomy [41]. It is worth noting that to avoid serous edema and serositis, the tying procedure should not be excessively tight. In addition, patients should be instructed to take early bed rest and choose the appropriate position after the operation of the ileostomy, avoid stoma contamination, replace the stoma bag in time, observe the surrounding skin and blood flow, pay close attention to the situation of the stoma, and actively prevent the occurrence of complications such as necrosis and edema.

To our knowledge, this current study was the first one to summarize the association between the stoma-related complications and method of temporary ileostomy. Meanwhile, some limitations existed in this study. First, all the six studies were retrospective studies and were from China, and the sample size of the included studies was relatively small, so more detailed randomized controlled trials from other regions were needed for comprehensive analysis. Second, the operation time of each ileostomy procedure was lacking. And third, the information of detailed complications was lacking in almost the studies we included, so we could not conduct a subgroup analysis in the detailed complications, early complications, and delayed complications.

In conclusion, the OM group had shorter operation time in both the primary LLAR surgery and the stoma reversal surgery than the TM group. Moreover, the OM group had less overall stoma-related complications. This surgical method was safe, effective, and worth promoting in clinical works.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Allen SK, Schwab KE, Rockall TA. Surgical steps for standard laparoscopic low anterior resection. Minerva Chir. 2018;73:227–38. https://doi.org/10.23736/s0026-4733.18.07572-7.

Liu XY, et al. Predictors associated with planned and unplanned admission to intensive care units after colorectal cancer surgery: a retrospective study. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30:5099–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-06939-1.

Hoshino N, Fukui Y, Hida K, Obama K. Similarities and differences between study designs in short- and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic versus open low anterior resection for rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, case-matched, and cohort studies. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2021;5:183–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/ags3.12409.

Liu XY, et al. Does preoperative waiting time affect the short-term outcomes and prognosis of colorectal cancer patients? A retrospective study from the West of China. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;2022:8235736. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/8235736.

Ye L, Huang M, Huang Y, Yu K, Wang X. Risk factors of postoperative low anterior resection syndrome for colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Asian J Surg. 2022;45:39–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asjsur.2021.05.016.

Croese AD, Lonie JM, Trollope AF, Vangaveti VN, Ho YH. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of low anterior resection syndrome and systematic review of risk factors. Int J Surg. 2018;56:234–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.06.031.

Nagaoka T, et al. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after laparoscopic low anterior resection: a single-center retrospective study. Asian J Endoscopic Surg. 2021;14:478–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/ases.12900.

Bulut A, Attaallah W. Completely diverted tube ileostomy versus conventional loop ileostomy. Cureus. 2022;14: e30997. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.30997.

Peng D, et al. Does temporary ileostomy via specimen extraction site affect the short outcomes and complications after laparoscopic low anterior resection in rectal cancer patients? A propensity score matching analysis. BMC Surg. 2022;22:263. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-022-01715-8.

Maeda S, et al. Safety and feasibility of temporary ileostomy in older patients: a retrospective study. Wound Manage Prevent. 2022;68:18–24.

Van Butsele J, Bislenghi G, D’Hoore A, Wolthuis AM. Readmission after rectal resection in the ERAS-era: is a loop ileostomy the Achilles heel? BMC Surg. 2021;21:267. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-021-01242-y.

Mrak K, et al. Diverting ileostomy versus no diversion after low anterior resection for rectal cancer: a prospective, randomized, multicenter trial. Surgery. 2016;159:1129–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2015.11.006.

Babakhanlou R, Larkin K, Hita AG, Stroh J, Yeung SC. Stoma-related complications and emergencies. Int J Emerg Med. 2022;15:17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-022-00421-9.

Rolls N, Yssing C, Bøgelund M, Håkan-Bloch J, de Fries Jensen L. Utilities associated with stoma-related complications: peristomal skin complications and leakages. J Med Econ. 2022;25:1005–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2022.2101776.

Ye H, et al. Comparison of the clinical outcomes of skin bridge loop ileostomy and traditional loop ileostomy in patients with low rectal cancer. Sci Rep. 2021;11:9101. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-88674-x.

Pei W, et al. One-stitch method vs. traditional method of protective loop ileostomy for rectal cancer: the impact of BMI obesity. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2021;147:2709–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-021-03556-z.

Chen Y, et al. One-stitch versus traditional method of protective loop ileostomy in laparoscopic low anterior rectal resection: A retrospective comparative study. Int J Surg. 2020;80:117–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.06.035.

Li X, Tian M, Chen J, Liu Y, Tian H. Integration of prolapsing technique and one-stitch method of ileostomy during laparoscopic low anterior resection for rectal cancer: a retrospective study. Front Surg. 2023;10:1193265. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2023.1193265.

Hu L, et al. Application of simple support bracket combined with one stitch suture in terminal ileostomy of rectal cancer. J Surg Concepts Pract. 2023;28:77–82. https://doi.org/10.16139/j.1007-9610.2023.01.13.

Zhang L, et al. Modified one- stitch method of prophylactic ileostomy in laparoscopic low anterior resection for patients with rectal cancer. J Colorectal Anal Surger. 2022;28:163–6. https://doi.org/10.19668/j.cnki.issn1674-0491.2022.02.013.

Wang C, Shi Y. Application of one stitch method of prophylactic ileostomy via Ventral white line in laparoscopic anterior resection. Chin J Curr Adv Gen Surg. 2022;25:214–5. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1009-9905.2022.03.010.

Shamseer L, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;350: g7647. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7647.

Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z.

Ioannidis JP. Interpretation of tests of heterogeneity and bias in meta-analysis. J Eval Clin Pract. 2008;14:951–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.00986.x.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measur Inconsist Meta-Anal Bmj. 2003;327:557–60. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557.

Mu Y, Zhao L, He H, Zhao H, Li J. The efficacy of ileostomy after laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery: a meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2021;19:318. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-021-02432-x.

Palumbo P, et al. Anastomotic leakage in rectal surgery: role of the ghost ileostomy. Anticancer Res. 2019;39:2975–83. https://doi.org/10.21873/anticanres.13429.

Sullivan NJ, et al. Early vs standard reversal ileostomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Techniq Coloproctol. 2022;26:851–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-022-02629-6.

Mengual-Ballester M, et al. Protective ileostomy: complications and mortality associated with its closure. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2012;104:350–4. https://doi.org/10.4321/s1130-01082012000700003.

Liu XR, et al. Do colorectal cancer patients with a postoperative stoma have sexual problems? A pooling up analysis of 2566 patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2023;38:79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-023-04372-2.

Climent M, et al. Prognostic factors for complications after loop ileostomy reversal. Tech Coloproctol. 2022;26:45–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-021-02538-0.

Fielding A, et al. Renal impairment after ileostomy formation: a frequent event with long-term consequences. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22:269–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.14866.

Martellucci J, et al. Ileostomy versus colostomy: impact on functional outcomes after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.16657.

De Robles MS, Bakhtiar A, Young CJ. Obesity is a significant risk factor for ileostomy site incisional hernia following reversal. ANZ J Surg. 2019;89:399–402. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.14983.

Su H, et al. Satisfactory short-term outcome of total laparoscopic loop ileostomy reversal in obese patients: a comparative study with open techniques. Updat Surg. 2021;73:561–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-020-00890-8.

Bafford AC, Irani JL. Management and complications of stomas. Surg Clin North Am. 2013;93:145–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suc.2012.09.015.

Forsmo HM, et al. Pre- and postoperative stoma education and guidance within an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programme reduces length of hospital stay in colorectal surgery. Int J Surg. 2016;36:121–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.10.031.

An institutional study. Rubio-Perez, I., Leon, M., Pastor, D., Diaz Dominguez, J. & Cantero, R. Increased postoperative complications after protective ileostomy closure delay. World Journal of Gastroint Surg. 2014;6:169–74. https://doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v6.i9.169.

Bhalerao S, Scriven MW, da Silva A. Stoma related complications are more frequent after transverse colostomy than loop ileostomy: a prospective randomized clinical trial. Br J Surg. 2002;89:495. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.208816.x.

Zhao Y, et al. Application of one-stitch preventive ileostomy in anterior resection of low rectal cancer. Chin J Colorectal Dis. 2020;9:157–61. https://doi.org/10.3877/cma.j.issn.2095-3224.2020.02.009.

Garnjobst W, Leaverton GH, Sullivan ES. Safety of colostomy closure. Am J Surg. 1978;136:85–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9610(78)90205-2.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all the authors whose publications are referred in our article.

Funding

No funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yong Cheng contributed to conception and design of the study. Xin-Peng Shu and Quan Lv collected the data. Dong Peng finished the statistical analysis. Xin-Peng Shu and Quan Lv wrote the first-draft manuscript. All authors contributed to revise the manuscript, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publications

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shu, XP., Lv, Q., Li, ZW. et al. Does one-stitch method of temporary ileostomy affect the stoma-related complications after laparoscopic low anterior resection in rectal cancer patients?. Eur J Med Res 29, 403 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-024-01995-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-024-01995-1