Abstract

Context

Studies generally focus on one type of chronic condition and the effect of medical cannabis (MC) on symptoms; little is known about the perceptions and engagement of patients living with chronic conditions regarding the use of MC.

Objectives

This scoping review aims to explore: (1) what are the dimensions addressed in studies on MC that deal with patients' perceptions of MC? and (2) how have patients been engaged in developing these studies and their methodologies? Through these objectives, we have identified areas for improving future research.

Methods

We searched five databases and applied exclusion criteria to select relevant articles. A thematic analysis approach was used to identify the main themes: (1) reasons to use, to stop using or not to use MC, (2) effects of MC on patients themselves and empowerment, (3) perspective and knowledge about MC, and (4) discussion with relatives and healthcare professionals.

Results

Of 53 articles, the main interest when assessing the perceptions of MC is to identify the reasons to use MC (n = 39), while few articles focused on the reasons leading to stop using MC (n = 13). The majority (85%) appraise the effects of MC as perceived by patients. Less than one third assessed patients’ sense of empowerment. Articles determining the beliefs surrounding and knowledge of MC (n = 41) generally addressed the concerns about or the comfort level with respect to using MC. Only six articles assessed patients’ stereotypes regarding cannabis. Concerns about stigma constituted the main topic while assessing relationships with relatives. Some articles included patients in the research, but none of them had co-created the data collection tool with patients.

Conclusions

Our review outlined that few studies considered chronic diseases as a whole and that few patients are involved in the co-construction of data collection tools as well. There is an evidence gap concerning the results in terms of methodological quality when engaging patients in their design. Future research should evaluate why cannabis’ effectiveness varies between patients, and how access affects the decision to use or not to use MC, particularly regarding the relationship between patients and healthcare providers. Future research should consider age and gender while assessing perceptions and should take into consideration the legislation status of cannabis as these factors could in fact shape perception. To reduce stigma and stereotypes about MC users, better quality and accessible information on MC should be disseminated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic diseases are collectively responsible for about 70% of all deaths worldwide, placing a growing burden on individuals and healthcare systems around the world [1]. Besides this impact on mortality, their load of morbidity is not to be underestimated. In fact, as most chronic conditions still have no cure, they require lifelong follow-up, self-management, adherence to treatment and timely intervention when necessary [2]. Given their duration, some people living with chronic conditions can experience emotional stress and chronic pain, which are both associated with the development of depression and anxiety. [3]

In this context, patients with oncological and non-oncological chronic conditions should play an increasingly important role in managing their illness [4, 5]. Engaging them in the self-management of their chronic conditions could help increase their quality of life by carrying out normal roles and activities, and manage the physical and emotional impact of their illness [6,7,8]. Support in self-management by healthcare providers has been shown to help patients deal with their symptoms more efficiently and can also help these patients to “gain the confidence, knowledge, skills, and motivation to manage the physical, social, and emotional impacts of their disease” [9]. However, some factors, such as comorbidities or psychosocial vulnerability, can further challenge providers' care and patients' self-management. These issues can undermine patient participation in care and affect treatment adherence and attendance. [10]

Therapeutic benefits of medical cannabis (MC) have been demonstrated across a broad spectrum of medical conditions and symptoms and can act as an analgesic, anticonvulsant, and antispasmodic for a wide range of chronic conditions [11]. Chronic pain and co-occurring conditions are among the most common conditions for which cannabinoid-based products, mainly containing Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and/or cannabidiol (CBD), are used for therapeutic purposes [12], knowing, however, that there are uncertainties and controversies about the role and appropriate use of cannabis-based medicines in the management of chronic pain [13]. Other than non-prescribed cannabis, some patients have access to cannabinoid-based products to alleviate symptoms specific to their chronic disease such as Sativex® for multiple sclerosis, Cesamet® for chemotherapy, Marinol® for AIDS and chemotherapy, and Epidiolex® for epilepsy [14]. Although these products are not without risks, the “majority of reported adverse events tends to be mild and self-limiting.” [15].

Even if some studies have shown MC to be effective in managing chronic pain [16] and in improving quality of life [17], some healthcare providers may be reluctant to discuss and support patients’ use of MC due to concerns about the quality of evidence and general lack of information [18] on or lack of knowledge of MC dosing and about how to create treatment plans with MC [19].

Studying the perception of people with chronic conditions of MC and their motivations to use it should help to identify its major issues to eventually produce coherent treatment plans. Moreover, involving patients in the construction of such studies should also add relevant elements to the analysis. Indeed, directly involving patients in research, in the recruitment or tools development, could help better assess these challenges and facilitators in patients’ self-management [20, 21], since they can help identify crucial elements that could have otherwise been overlooked. [22,23,24].

MC is a growing interest in clinical research and for chronically ill patients. While potential benefits or harms of MC are still under research, MC is considered an option for a complementary treatment by patients [25]. In this context, knowing how and to what extent the perceptions of the population affected by oncological and non-oncological diseases are covered should shed light on potential predisposing factors enabling or not the use of MC. Finally, as this subject pertains directly to the subjectivity of patients, having this population involved in the creation of the research design and outcome measures could give insights otherwise overlooked. Consequently, it is important to observe the degree to which this population is involved in the construction of those tools.

In this context, the primary objective of this scoping review is to map out and analyze the literature on the perception and engagement of patients living with oncological and non-oncological chronic conditions regarding the use of MC. This was achieved through two distinct questions: (1) What are the dimensions addressed in studies on MC that deal with patients' perception of MC? and (2) how have patients been engaged in developing these studies and their methodologies?

Through these questions, we hope to highlight gaps in the literature and suggest avenues for future research.

Materials and methods

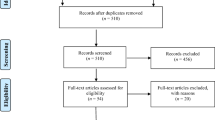

We followed the phases of the flow diagram developed by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA–ScR) to apply a systematic approach when conducting the review and reporting the results [26]. The scoping review was also conducted in accordance with the multistage framework outlined by Arksey and O’Malley [27] and JBI synthesis evidence [28,29,30], as detailed in the following sections.

Identifying relevant studies

To initiate the literature search, we have identified six major concepts related to: patients, oncological and non-oncological chronic disease, perceptions, cannabis, medical use, and effects. The latter was added to find associated factors that could have an impact on patients’ perceptions. All descriptors are presented in Table 1. The search strategy was based on five major health and social science databases: Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, Elsevier Scopus, Clarivate Web of Science, and EBSCO CINAHL. The initial search was conducted on November 29, 2021 to capture publication from 2002 to 2022 and another was conducted on September 27, 2022 for publications from 2021 to 2022. Our search strategy was restricted to published and peer-reviewed literature and we did not conduct any searches in the gray literature. The search strategies are available in supplementary files (Additional file 1).

Study selection

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed in Table 2. The references were managed with EndNote. After removing duplicates, four reviewers (J.P., D.L.I., M.T., and K.S.) independently screened articles based on their titles and abstracts using Rayyan. A pilot round was conducted with 50 references to verify the reviewers’ agreement on the inclusion and exclusion criteria based on the title and abstract of each before performing a full screening of the rest of the articles. Discrepancies were resolved through team discussion and consensus. The senior authors (M.P.P. and D.J.A.) screened articles of uncertain relevance for final inclusion or exclusion.

Charting the data

Data from the included articles was charted on an extraction grid (Additional file 2) according to the following categories: authors, title, journal, year of publication, study location, type of chronic disease, aims of the study and method used to collect data.

Collating, summarizing and reporting the results

We used a thematic analysis approach to identify, analyse and report patterns or themes in the literature. This approach allows adaptability and flexibility to refine or create new categorizations if needed [31, 32]. The first step in the data synthesis was to become familiar with the data by reading full texts to identify a wide range of subjects that were then grouped into main themes that assess the perceptions and engagement of patients with chronic diseases about MC [33]. Some themes were then merged to form broader categories to synthesize the information and facilitate the reporting of results. Finally, the themes were refined according to the research objectives. The final themes were then used to analyze the articles by two coders (J.P., K.S.).

We also assessed the level of patients’ involvement in the research process of the included articles. Involving patients in the research process as opposed to conducting research for or about them is the definition of Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) [33]. Patients’ involvement can testify to the quality, relevance and impact of the research by improving researchers’ transparency and accountability [33]. To evaluate the level of engagement in research, we used the continuum of patient involvement in research [34]. We considered three levels of involvement: (1) consultation of patients, which refers to asking for patients' input during the themes of identification or tool validation; (2) collaboration with patients, which corresponds to involving them in the selection and wording of items in the questionnaire or interview guide; and (3) partnership, which refers to co-constructing the tool with patients, from its development to its validation.

Results

Search results

Our search yielded a total of 5974 articles. After removing duplicates, a total of 3516 articles were screened. This process resulted in a total of 73 full text articles to be assessed for eligibility. Following reviews of full-text articles, 53 articles met the inclusion criteria [11, 37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92]. The PRISMA flow diagram has been provided (see Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

We identified a total of 53 articles based on eligibility criteria for assessing the perceptions of patients living with oncological and non-oncological chronic conditions of therapeutic cannabis, both prescribed and self-purchased. The extraction grid with the identification and analysis of articles has been presented (see Additional file 2). The included studies were published in 45 different journals, from 2003 to 2022 in 14 different countries, with the United States, Canada and Australia being the most represented ones. The chronic conditions studied are presented in (Table 3). Studies collected data through surveys (74%, n = 39), interviews (19%, n = 10), or focus groups (8%, n = 4) (see Additional file 2). Five articles took into consideration sex and age while assessing attitude, methods and dosage of MC consumption. Sixteen articles included a focus on cannabis legislation as a contributing factor in the analysis of medical cannabis consumption patterns and attitudes toward medical cannabis. Sample size ranged from 4 to 2701, with focus groups and interviews having fewer participants than surveys. Conflicts of interests were reported in 13 articles (25%) (see Additional file 2), including: (1) receiving funding, grants, honoraria or personal fees from research pertaining to chronic diseases, organizations or pharmaceutical or MC-related companies; (2) being in a high position (e.g., founder, chief executive officer, board member) or a consultant with those organizations or companies; (3) obtaining free products; (4) having patents pending; (5) being an authorized MC grower and distributor; and (6) reporting data from participants from the same consulting MC company.

Patients’ engagement in research

In terms of patients’ engagement, 12 articles have involved patients in the research process. Five studies (9%) were engaging patients at the first level of involvement (consultation) to identify the main themes to include in the questionnaire (see Additional file 2), four articles involved patients in reviewing the questionnaire once it was created (8%), (see Additional file 2), and four engaged patients for pilot-testing the tool once it was developed (7%) (see Additional File 2). One collaborated with patients by involving them at the beginning (identification of themes) and at the end of the questionnaire creation (feedback on the final version) (see Additional file 2). This can be considered as collaboration, hence the second level of involvement, but not co-creation since patients have not constructed the tool design with researchers and were not involved beyond the tool development stage.

Perception of MC

Regarding thematic analysis related to how patients’ perception of MC is evaluated in the literature, four main themes were identified: (1) reasons to use, to stop using or not to use MC; (2) beliefs about and knowledge of MC; (3) effects of MC on patients themselves and empowerment; and (4) discussion of MC with relatives and healthcare professionals.

Reasons to use, to stop using or not use MC

Of 53 articles, 43 of them studied the motivations behind patients’ decision to use, to stop using or not to use MC (81%) of which 39 inquired about the reasons of use (74%), 13 about why they stopped using MC (25%), and 25 about reasons of non-use (47%) (see Additional file 2). Only five articles asked questions about the three categories (9%) (see Additional file 2).

Reasons cited to use MC include: symptoms’ improvement (47%, n = 25), reasons in relation to other medications being taken (e.g., to be used in conjunction with other medications, to reduce the uptake of other medications or because the medication was ineffective; 24%, n = 17), quality of life improvement (23%, n = 12), reasons in relation to the disease (e.g., coping with the disease, healing or stopping its progression; 21% n = 11), information found or discussion (e.g., recommendation from a healthcare provider or a relative, or personal research; 23%, n = 12), and ease of access to MC (2%, n = 1) (see Additional file 2).

Reasons to stop using MC include: ineffectiveness or loss of interest in using MC (17%, n = 9), side effects caused by MC (15%, n = 8), concerns about MC (e.g., product legality or security, stigma; 11%, n = 6), access difficulties (11%, n = 6), and advice from healthcare providers or relatives (8%, n = 4) (see Additional file 2).

Reasons not to use MC for treatment of chronic disease include: access difficulties (36%, n = 19), concerns about MC (e.g., impact on health, work or social life; 28%, n = 15), research missing or lack of information on MC (26%, n = 14), advice from healthcare providers or relatives (13%, n = 7), and personal choice (13%, n = 7) (see Additional file 2).

An overwhelming majority did not consider the legal status of cannabis when assessing the environment to use or not to use MC, and only six articles considered the legality of MC in association with the intention to use MC (see Additional file 2).

Perceived effects of MC on patients themselves and empowerment

When assessing perception of MC, 45 articles focused on a biological level and described the results of perceived treatment by studying the effect that MC had on patients living with chronic diseases (85%) (see Additional file 2). Most studies asked patients questions about the effect of MC on their disease’s symptoms (75%, n = 40), and some inquired about new perceived side effects on self and symptoms (47%, n = 25) and MC effects on quality of life (38%, n = 20) (see Additional file 2). Only a few have addressed MC effects compared to other medications (6%, n = 3), its effect on the disease progression (9% n = 5), the impact on lifestyle habits (e.g., change in their views about MC or in behaviour; 4%, n = 2), and the impact on self-image (e.g., affirming self-worth or sense of belonging; 2%, n = 1) (see Additional file 2). Fifteen articles studied perceived effects in terms of the empowerment MC had on patients (28%), such as decision-making in their own care or treatment path (e.g., reducing or stopping other medications, preventing other medical interventions, selecting best products for self, or managing MC dose; 21%, n = 11), and the will to participate in research activities (e.g., conducting research to educate themselves, or participating in clinical trials; 6%, n = 3) (see Additional file 2). Some studies have also noted the positive feelings of empowered patients, such as a comforted feeling for being in control (8%, n = 4) (see Additional file 2).

Beliefs about and knowledge of MC

Out of the 53 articles included, 41 addressed the patients’ personal beliefs about MC (72%) (see additional file 2). Most inquired about concerns and risk perceptions (53%. n = 28), such as the perceived level of security, utility, and efficacy of MC, or concerns about access or product quality (see Additional file 2).

Almost half evaluated the social support or comfort level using MC (42%, n = 22) (see Additional file 2). Other elements analyzed included: comparison of MC with other medications (e.g., perception that cannabis is more natural, or safer than other medications, preferences or satisfaction level; 23%, n = 12), stereotypes (e.g., belief that MC is addictive, that it is a gateway drug, that its withdrawal can be life-threatening or that its users are prone to violence; 11%, n = 6), the impact of media and pharmaceutical companies (e.g., level of influence of the media on their opinion of cannabis, degree of trust in pharmaceutical companies; 6%, n = 3), the expected effects on those who plan to use MC (4%, n = 2), and the conditions of use of MC (e.g., should only be taken under the guidance of physicians or should be made available to people with qualifying conditions; 4%, n = 2) (see Additional file 2).

In addition, 29 articles evaluated the patients’ knowledge of MC (55%). More specifically, questions were related to: information research on MC (e.g., their interest in seeking information, the sources used to find information, the quality of information found, the level of trust in media as a source of information; 38%, n = 20), general knowledge of MC (e.g., different cannabis compounds, consumption methods, laws, what it can treat; 23%, n = 12), and on MC effects (e.g., benefits and side effects, parts of the brain affected by cannabis; 19%, n = 10).

Discussion about MC with relatives and healthcare professionals

Twenty-two articles inquired about discussion with the patients’ relatives (42%). Elements of discussion included: concerns about or experienced stigma (19%, n = 10), level of comfort discussing MC (17%, n = 9), advice received from relatives to use MC (MC recommended by relatives MC; 15%, n = 8), level of support received (13%, n = 7), and cannabis use by relatives (11%, n = 6).

Moreover, 27 articles evaluated patients’ discussions with healthcare professionals (51%). About a third assessed the perceived attitude of the healthcare provider (e.g., reaction, level of support received, perceived openness of the professionals to discuss MC; 30%, n = 16), and whether patients have requested information about MC or disclosed their MC use (28%, n = 15). The relationship with healthcare professionals, such as the patients’ comfort level discussing taking MC or the level of trust in the healthcare professionals (e.g., decision to prescribe or not, knowledge of the subject) was assessed in 17% of articles (n = 9). Other specific elements of discussion (e.g., if they received a prescription, if they asked the professional for advice on how to use the product, who initiated the conversation) were present in 21% of articles (n = 8).

Discussion

The aim of this scoping review was to map out the literature pertaining to how the perception and engagement by people with oncological and non-oncological chronic diseases about MC is evaluated in the literature and how those people are engaged in research related to that topic. Of 53 eligible articles for our analysis, only three have focused on chronic diseases in general, as 50 assessed the perception of patients with a specific chronic condition. As mentioned in the introduction, chronic conditions not only affect a person on a biological level, but also impact their life on a daily basis [3, 35]. Therefore, self-management plays a vital role in patients’ lives and is crucial to longevity and health-related quality of life [7]. As such, our results showed that self-management strategies, including the use of MC, can help patients gain control of the decision-making in their treatment path, and increase their willingness to participate in research activities.

Thematics identified

MC effects and outcomes

When assessing perceptions of MC, the main interest was to capture reasons to use MC. The most common reason to use MC mentioned in the included articles were to improve symptoms, which is consistent with existing literature, where chronic pain is one of the most common conditions to use cannabis for therapeutic reasons [12]. It has been shown that MC can be effective in managing chronic pain [18], and that plant-based cannabis preparations alleviate neuropathic pain. [36] Almost 40% of articles also included quality of life improvements as a reason to use MC, of which some have shown MC to be effective in improving quality of life [19]. MC as having a different status of legality can hinder research on cannabis but also impact the perception of this substance. As research on cannabis is relatively new (the oldest article included is from 2003), there is a need for research with different modalities with respect to diseases, areas with a different legal status of MC, dosing, cannabinoids, and methods of consumption.

Moreover, our results show that the main reason included in articles for patients to stop using MC is ineffectiveness, followed by side effects caused by MC. This topic, however, was covered by only a minority of the included articles. Developing interest in this topic could shed some light on reasons for adherence and observance of treatment. When assessing the perceptions of chronically ill patients of MC, our findings show that this topic is understood in terms of perceived effectiveness. Only 20% of articles have looked at empowerment, decision-making or self-image. It would be pertinent to develop interest in patients' own management of MC, which could help healthcare providers to understand patients’ adherence to and observance of treatment strategies.

Our results show that reasons in relation to other medications taken (either to use MC in conjunction or as a replacement of other medication) and in relation to the disease (e.g., coping with the disease, healing or stopping its progression) are analyzed in the literature as reasons to use MC. It would thus be relevant to further assess why some medications do not work and how joint use of MC and medication affects patients. McCallum and Russo also suggested that clinicians must gain a better understanding of MC dosing and administration methods to maximize therapeutic potential and minimize adverse events. [37]

Access to medical cannabis

Only one article cited the ease of access as a reason to use MC, while six articles assessed access difficulties as a reason to stop MC, whereas a lack of access was the main reason analyzed for not using MC. This imbalance shows that it may be pertinent to explore the possibility that access could be a main factor for patients with chronic disease to seek MC usage. Indeed, Kim and Monte [38] showed that cannabis availability and use in Colorado significantly increased after the legalization of marijuana. Moreover, access discrepancy should be further studied, as Walsh and al [39]. found that, in countries where MC is illegal, “authorized” and “unauthorized” users face substantial differences regarding access, and accessing cannabis from illegal markets may increase stigma, legal sanction, and other negative outcomes. Even in countries where MC has been legalized, and public acceptance of cannabis continues to grow, it appears that MC users “remain highly vulnerable to stigma at both interpersonal and institutional levels.” [40] Thus, more efforts should be made to better understand how access affects the decision for people living with chronic conditions to use or not to use MC. Additionally, healthcare providers or informative documents could better explain to patients how to have access to MC, both in countries where MC is legal and illegal.

There is also a need to further explore the relationship between healthcare providers and patients as a barrier to MC access. Indeed, our results show that less than a quarter of articles assessed different elements of relationship (such as the patients’ comfort level in engaging in discussions with healthcare professionals or their level of trust in them), even though studies have shown that some patients “fail to receive appropriate assessment and treatment for a health condition because of being labeled as drug dependent or a pothead” and that stigma about MC can strain the healthcare provider–patient relationship [40, 41]. It is therefore crucial to increase research on the professionals’ level of comfort in discussing MC with patients as well as patients’ comfort and trust level toward their healthcare provider.

Medical cannabis education

When studying reasons to stop using MC, we found that the information obtained from personal research or discussion with HCP and relatives accounts for 38%, 51% and 42%, respectively. Surprisingly, those factors are the less studied aspect in the literature. To better understand the decision-making on MC consumption, it is important to further explore how information found on cannabis has an impact in patients’ decision to stop using MC. One reason that may explain this is the low trust level in the media and in pharmaceutical companies. Indeed, our results show that only 6% of articles have assessed their decision to use or not MC according to trust levels and levels of suspicion concerning information shared by the media. This underlines a need for better assessment of these topics and more transfer of knowledge from official sources. Low trust in the media or high suspicion could indicate the need for quality and popularized information available to the public from sources that people can trust.

Another reason that may explain why patients stop using MC can be based on personal biases. Only six articles assess patients’ stereotypes such as preconceived notions about MC regarding addiction, withdrawal, characteristics of MC users (e.g., prone to violence), and risk to lead to stronger drugs. To reduce stigma about MC users, we believe further research must focus on these perceptions to better understand the stereotypes still present in society and to inform the population about them by providing accurate and targeted information. Moreover, as suggested in Bottorf et al. healthcare professionals should receive updated educational training to better guide and advise patients on MC use. [40]

Patient partnership in research

Our results show that although twelve studies have involved patients into the research process, including one at the second level of the engagement continuum [34], none has co-created the questionnaire with patients. Out of 53 articles, only two assessed patients’ beliefs in a broader manner, including not only the concerns and risks, but also the expected effects. Considering that some patients choose to start using MC based on their personal research, it is important to include every aspect pertaining to the use of MC, to prevent unintentional bias with the information available emphasizing only specific areas of MC consumption and beliefs. Finally, only 4% of the articles (n = 2) specifically questioned the patients about the barriers for seeking information from their healthcare professional.

Therefore, including patients in research could help identify crucial elements to include in data collection tools, and help interpret results. This would guarantee that their perspectives contribute essential elements to research findings, aspects that might be neglected otherwise [22].

However, the studies in which patients have been engaged have not relayed how this involvement impacted the quality of methodology. It would be pertinent for future research to analyze how their collaboration with patients impacts research and findings.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this article is the first scoping review analyzing which thematics are treated to assess the perception and engagement of patients with chronic conditions with respect to MC. Nevertheless, this review has several limitations. First, the literature research was limited to five databases and papers that were published in English or French only, so relevant studies in other languages might have been missed. We also did not conduct a gray literature search for unpublished data in this area and have excluded preprints that may have held relevant information. We chose to prioritize published and peer-reviewed articles to ensure the quality of the data. We abstain from doing a hand-searching of key journals to find articles that are missing in database and reference list searches, having already identified more than 5000 articles in databases. We also did not update the literature for papers published after 2022. However, some studies had conflicts of interests (n = 13), especially regarding the different levels of involvement of some authors in MC companies or in MC-promoting organizations which may have impacted the lens through which their questionnaires were conceptualized, as well as their studies’ outcomes. Second, the fact that we conducted a literature review addressing a broad variety of chronic diseases rather than a specific one, may be considered to be both a strength and a limitation. It portrays a rich overview of the several themes of interest on MC; however, given the fact that most of the articles reviewed in this study focused on one specific disease, it is less evident to establish a general analysis. In addition, the exclusion of studies involving children or adolescents, as well as those related to non-chronic diseases, was a deliberate choice to maintain a focused scope in our current analysis. Therefore, complementary studies to ours might be relevant to enrich the overall understanding of the subject matter regarding these populations. In addition, the contextualization of gender and age as mere background data in the majority of studies poses a challenge to the generalizability of our findings. The selected studies where sex and age have been considered factors in assessing perception represent an underwhelming proportion (9%), while for the majority, it has been contextual data. Moreover, an essential facet that has been absent in the current body of literature is the consideration of ethnicity, which hinders a comprehensive understanding of mechanisms that can play a crucial role in shaping perceptions and attitudes toward MC. Similarly, our findings were limited as few articles considered the legal status of cannabis when assessing the intention to use and attitudes, which could greatly impact perceptions.

Conclusion

This scoping review has highlighted the fact that very few studies have focused on chronic conditions as a whole, and that none of the tools created to assess patients’ perspectives on MC were co-created with patients living with chronic conditions. With the increasing interest and use of MC, future research should focus on assessing the perceptions of these substances by patients by creating partnerships in research.

Moreover, our results show that the main reason included in articles for patients to stop using MC is ineffectiveness, followed by side effects of MC; such reason was not investigated in most included studies. Therefore, more efforts must be made to understand why cannabis is ineffective in certain patients and how its use affects patients. In addition, as the lack of access was the main reason analyzed for not using MC, more research should be made to better understand how access affects the decision for people living with chronic conditions to use or not to use MC, including the relationship between the healthcare professionals and the patients. Finally, this scoping review demonstrates that few articles have assessed patients’ representation of MC and their trust levels with respect to the media regarding their decision to use or not to use MC. Moreover, we noticed that negative effects of MC when assessing perception were not sufficiently studied and we suggest future research to study those aspects to prevent unintentional bias. We also observed a lack of sufficient data for each chronic condition to conclusively determine whether there exists a distinct perception regarding medical cannabis.

Age, gender, ethnicity of chronically ill patients and the legality of MC were not sufficiently studied. It would be pertinent for future research to assess perception according to those variables to gain a more accurate understanding of MC perceptions’ dynamics in different populations. This underlines a need for a more inclusive research outcome, better quality and accessible information available to the public from reliable sources.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the [NAME] repository, [PERSISTENT WEB LINK TO DATASETS].

Abbreviations

- AIDS:

-

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- CBD:

-

Cannabidiol

- MC:

-

Medical cannabis

- PRISMA–SCR:

-

Prisma extension for scoping reviews

- THC:

-

Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol

References

World health organization. noncommunicable diseases: progress monitor 2020. World Health Organization; 2020. Accessed 9 Sept, 2022. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/330805

Bernell S, Howard SW. Use your words carefully: what is a chronic disease? Front Public Health. 2016;4:159. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2016.00159.

Canadian Mental Health Association. (2008). The relationship between mental health, mental illness and chronic physical conditions. https://ontario.cmha.ca/documents/the-relationship-between-mental-health-mental-illness-and-chronic-physical-conditions/

Allegrante JP, Wells MT, Peterson JC. Interventions to support behavioral self-management of chronic diseases. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40:127–46. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-044008.

Anekwe TD, Rahkovsky I. Self-management: a comprehensive approach to management of chronic conditions. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(S6):S430–6. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302041r.

Reynolds R, Dennis S, Hasan I, et al. A systematic review of chronic disease management interventions in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19:11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-017-0692-3.

Basavaraj KH, Navya MA, Rashmi R. Quality of life in HIV/AIDS. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2010;31(2):75–80. https://doi.org/10.4103/2589-0557.74971.

Liddy C, Mill K. An environmental scan of policies in support of chronic disease self-management in Canada. Chronic Dis Inj Can. 2014;34(1):55–63.

Health Council of Canada. self-management support for canadians with chronic health conditions: A Focus for Primary Health Care. 2012. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2012/ccs-hcc/H174-28-2012-eng.pdf

Remien RH, Stirratt MJ, Nguyen N, Robbins RN, Pala AN, Mellins CA. Mental health and HIV/AIDS: the need for an integrated response. AIDS Lond Engl. 2019;33(9):1411–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000002227.

Bruce D, Brady JP, Foster E, Shattell M. Preferences for medical marijuana over prescription medications among persons living with chronic conditions: alternative, complementary, and tapering uses. J Altern Complement Med N Y N. 2018;24(2):146–53. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2017.0184.

Wright P, Walsh Z, Margolese S, et al. Canadian clinical practice guidelines for the use of plant-based cannabis and cannabinoid-based products in the management of chronic non-cancer pain and co-occurring conditions: protocol for a systematic literature review. BMJ Open. 2020;10(5): e036114. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-036114.

Häuser W, Finn DP, Kalso E, et al. European pain federation (EFIC) position paper on appropriate use of cannabis-based medicines and medical cannabis for chronic pain management. Eur J Pain. 2018;22:1547–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejp.1297.

Furrer D, Kröger E, Marcotte M, et al. Cannabis against chronic musculoskeletal pain: a scoping review on users and their perceptions. J Cannabis Res. 2021;3(1):41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42238-021-00096-8.

Lintzeris N, Driels J, Elias N, Arnold JC, McGregor IS, Allsop DJ. Medicinal cannabis in Australia, 2016: the cannabis as medicine survey (CAMS-16). Med J Aust. 2018;209(5):211–6. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja17.01247.

National Academies of Sciences E. The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids the current state of evidence and recommendations for research. Washington: National Academies Press; 2017. https://doi.org/10.17226/24625.

Peterson AM, Le C, Dautrich T. Measuring the change in health-related quality of life in patients using marijuana for pain relief. Med Cannabis Cannabinoids. 2021;4(2):114–20. https://doi.org/10.1159/000517857.

Jones C, Hathaway AD. Marijuana medicine and Canadian physicians: challenges to meaningful drug policy reform. Contemp Justice Rev. 2008;11(2):165–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/10282580802058429.

Ziemianski D, Capler R, Tekanoff R, Lacasse A, Luconi F, Ware MA. Cannabis in medicine: a national educational needs assessment among Canadian physicians. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0335-0.

Lorig KR, Holman HR. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_01.

Brady JP, Bruce D, Foster E, Shattell M. Self-efficacy in researching and obtaining medical cannabis by patients with chronic conditions. Health Educ Behav Off Publ Soc Public Health Educ. 2020;47(5):740–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198120914249.

Gagnon MP, Desmartis M, Lepage-Savary D, et al. Introducing patients’ and the public’s perspectives to health technology assessment: a systematic review of international experiences. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2011;27(1):31–42. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462310001315.

Dieudonné S, Demers I, Lavallée MS. Analyser la mesure de l’expérience patient une nouvelle approche de sondage pour mieux appréhender la perspective des usagers sur la qualité des soins. Point En Adm Santé Serv Sociaux. 2013;9(3):6–10.

Grosjean S, Bonneville L, Redpath C. The design process of an mhealth technology: the communicative constitution of patient engagement through a participatory design workshop ESSACHESS. J Commun Stud. 2019;1(23):5–26.

Fitzcharles MA, Eisenberg E. Medical cannabis: a forward vision for the clinician. Eur J Pain Lond Engl. 2018;22(3):485–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1185.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

Jordan Z, Lockwood C, Aromataris E, Munn Z. The updated JBI model for evidence-based healthcare. The Joanna Briggs Institute. 2016

Pearson A, Jordan Z, Munn Z. Translational science and evidence-based healthcare: a clarification and reconceptualization of how knowledge is generated and used in healthcare. Nursing Res Pract. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/792519.

Pearson A, Wiechula R, Court A, Lockwood C. The JBI model of evidence-based healthcare. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2005;3(8):207–15.

Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: thematic analysis and code development.

Guest G, MacQueen KM, Namey EE. Themes and codes applied thematic analysis. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Inc; 2012.

Brett J, Staniszewska S, Simera I, et al. Reaching consensus on reporting patient and public involvement (PPI) in research: methods and lessons learned from the development of reporting guidelines. BMJ Open. 2017;7(10): e016948. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016948.

Pomey MP, Flora L, Karazivan P, et al. The montreal model: the challenges of a partnership relationship between patients and healthcare professionals. Sante Publique. 2015. https://doi.org/10.3917/spub.150.0041.

Australian Institute of Health and WelfareAustralian Institute of Health and Welfare. About Chronic disease. Accessed 15 Sept, 2022. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-data/health-conditions-disability-deaths/chronic-disease/about

Humphreys K, Saitz R. Should physicians recommend replacing opioids with cannabis? JAMA. 2019;321(7):639–40. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.0077.

MacCallum CA, Russo EB. Practical considerations in medical cannabis administration and dosing. Eur J Intern Med. 2018;49:12–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2018.01.004.

Kim HS, Monte AA. Colorado cannabis legalization and its effect on emergency care. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68(1):71–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.01.004.

Walsh Z, Callaway R, Belle-Isle L, et al. Cannabis for therapeutic purposes: patient characteristics, access, and reasons for use. Int J Drug Policy. 2013;24(6):511–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.08.010.

Bottorff JL, Bissell LJ, Balneaves LG, Oliffe JL, Capler NR, Buxton J. Perceptions of cannabis as a stigmatized medicine: a qualitative descriptive study. Harm Reduct J. 2013;10(1):2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7517-10-2.

Belle-Isle L, Walsh Z, Callaway R, et al. Barriers to access for Canadians who use cannabis for therapeutic purposes. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(4):691–9.

AminiLari M, Kithulegoda N, Strachan P, MacKillop J, Wang L, Pallapothu S, et al. Benefits and concerns regarding use of cannabis for therapeutic purposes among people living with chronic pain: a qualitative research study. Pain Med. 2022;23(11):1828–36.

Beauchesne W, Ouellet-Dupuis F, Frigon MA, Savard C, Gagné-Ouellet V, Gagnon C, et al. Cannabis use in patients with autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of charlevoix-saguenay. J Clin Neurosci. 2022;103:44–8.

Belyea DA, Alhabshan R, del Rio-Gonzalez AM, Chadha N, Lamba T, Golshani C, et al. Marijuana use among patients with glaucoma in a city with legalized medical marijuana use. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(3):259.

Benson MJ, Abelev SV, Connor SJ, Corte CJ, Martin LJ, Gold LK, et al. Medicinal cannabis for inflammatory bowel disease: a survey of perspectives, experiences, and current use in Australian patients. Crohn’s Colitis. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/crocol/otaa015.

Bianconi F, Bonomo M, Marconi A, Kolliakou A, Stilo SA, Iyegbe C, et al. Differences in cannabis-related experiences between patients with a first episode of psychosis and controls. Psychol Med. 2016;46(5):995–1003.

Bobitt J, Kang H, Croker JA, Quintero Silva L, Kaskie B. Use of cannabis and opioids for chronic pain by older adults: distinguishing clinical and contextual influences. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2020;39(6):753–62.

Boehnke KF, Gagnier JJ, Matallana L, Williams DA. Cannabidiol use for fibromyalgia: prevalence of use and perceptions of effectiveness in a large online survey. J Pain. 2021;22(5):556–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2020.12.001.

Boehnke KF, Gagnier JJ, Matallana L, Williams DA. Cannabidiol product dosing and decision-making in a national survey of individuals with fibromyalgia. J Pain. 2022;23(1):45–54.

Bourke JA, Catherwood VJ, Nunnerley JL, Martin RA, Levack WMM, Thompson BL, et al. Using cannabis for pain management after spinal cord injury: a qualitative study. Spinal Cord Ser Cases. 2019;5(1):82.

Buadze A, Stohler R, Schulze B, Schaub M, Liebrenz M. Do patients think cannabis causes schizophrenia?—a qualitative study on the causal beliefs of cannabis using patients with schizophrenia. Harm Reduct J. 2010;7(1):22.

Butler T, Hande K, Ryan M, Raman R, McDowell MR, Cones B, et al. Cannabidiol: knowledge, beliefs, and experiences of patients with cancer. CJON. 2021;25(4):405–12.

Carnero Contentti E, López PA, Criniti J, et al. Use of cannabis in patients with multiple sclerosis from Argentina. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021;51: 102932. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2021.102932.

Costiniuk CT, Saneei Z, Salahuddin S, Cox J, Routy JP, Rueda S, et al. Cannabis consumption in people living with HIV: reasons for use, secondary effects, and opportunities for health education. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2019;4(3):204–13.

Erga AH, Maple-Grødem J, Alves G. Cannabis use in Parkinson’s disease—a nationwide online survey study. Acta Neuro Scandinavica. 2022;145(6):692–7.

Fader L, Scharf Z, DeGeorge BR. Assessment of medical cannabis in patients with osteoarthritis of the thumb basal joint. J Hand Surg. 2021;48(3):257.

Fennell B, Magnan R, Ladd B, Fales J. Young adult cannabis users’ perceptions of cannabis risks and benefits by chronic pain status. Subst Use Misuse. 2022;57(11):1647–57.

Francoeur N, Baker C. L’attirance qu’éprouvent les hommes atteints de schizophrénie pour le cannabis : une étude phénoménologique. 2010. 42(1).

Friedberg J. (2017). Medical cannabis: Four patient perspectives. Journal of Pain Management.

Han J, Faletsky A, Mostaghimi A, Huang K. Cannabis use among patients with alopecia areata: a cross-sectional survey study. Int J Trichol. 2022;14(1):21.

Hawley P, Gobbo M. Cannabis use in cancer: a survey of the current state at BC cancer before recreational legalization in Canada. Curr Oncol. 2019;26(4):e425–32. https://doi.org/10.3747/co.26.4743.

Hulaihel A, Gliksberg O, Feingold D, Brill S, Amit BH, Lev-ran S, et al. Medical cannabis and stigma: a qualitative study with patients living with chronic pain. J Clin Nursing. 2022;32(7):1102.

Krediet E, Janssen DG, Heerdink ER, Egberts TC, Vermetten E. Experiences with medical cannabis in the treatment of veterans with PTSD: results from a focus group discussion. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;36:244–54.

Levin M, Zhang H, Gupta MK. Attitudes toward and acceptability of medical marijuana use among head and neck cancer patients. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2023;132(1):13–8.

Luckett T, Phillips J, Lintzeris N, Allsop D, Lee J, Solowij N, et al. Clinical trials of medicinal cannabis for appetite-related symptoms from advanced cancer: a survey of preferences, attitudes and beliefs among patients willing to consider participation: patient survey to inform cannabis trials. Intern Med J. 2016;46(11):1269–75.

Manning L, Bouchard L. Medical cannabis use: exploring the perceptions and experiences of older adults with chronic conditions. Clin Gerontol. 2021;44(1):32–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2020.1853299.

Manyau MC, Changadzo KP, Mudziti T. Perceptions and prevalence of marijuana use among cancer patients managed at an outpatient department in Zimbabwe: a brief report. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1177/10781552221118026.

Melinyshyn AN, Amoozegar F. Cannabinoid use in a tertiary headache clinic: a cross-sectional survey. Can J Neurol Sci. 2022;49(6):781–90.

Merker AM, Riaz M, Friedman S, Allegretti JR, Korzenik J. Legalization of medicinal marijuana has minimal impact on use patterns in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24(11):2309–14.

Mousa A, Petrovic M, Fleshner NE. Prevalence and predictors of cannabis use among men receiving androgen-deprivation therapy for advanced prostate cancer. CUAJ. 2020. https://doi.org/10.5489/cuaj.5911.

Neufeld T, Pfuhlmann K, Stock-Schröer B, Kairey L, Bauer N, Häuser W, et al. Cannabis use of patients with inflammatory bowel disease in Germany: a cross-sectional survey. Z Gastroenterol. 2021;59(10):1068–77.

Page SA, Verhoef MJ, Stebbins RA, Metz LM, Levy JC. Cannabis use as described by people with multiple sclerosis. Can J Neurol Sci. 2003;30(3):201–5. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0317167100002584.

Pergam SA, Woodfield MC, Lee CM, Cheng GS, Baker KK, Marquis SR, et al. Cannabis use among patients at a comprehensive cancer center in a state with legalized medicinal and recreational use: Cannabis use in cancer patients. Cancer. 2017;123(22):4488–97.

Piper BJ, Beals ML, Abess AT, Nichols SD, Martin MW, Cobb CM, et al. Chronic pain patients’ perspectives of medical cannabis. Pain. 2017;158(7):1373–9.

Potts JM, Getachew B, Vu M, Nehl E, Yeager KA, Leach CR, et al. Use and perceptions of opioids versus marijuana among cancer survivors. J Canc Educ. 2022;37(1):91–101.

Puteikis K, Mameniškienė R. Use of cannabis and its products among patients in a tertiary epilepsy center: a cross-sectional survey. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;111: 107214.

Reblin M, Sahebjam S, Peeri NC, Martinez YC, Thompson Z, Egan KM. Medical cannabis use in glioma patients treated at a comprehensive cancer center in Florida. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(10):1202–7.

Schilling JM, Hughes CG, Wallace MS, Sexton M, Backonja M, Moeller-Bertram T. Cannabidiol as a treatment for chronic pain: a survey of patients’ perspectives and attitudes. JPR. 2021;14:1241–50.

Sinclair J, Armour S, Akowuah JA, Proudfoot A, Armour M. “Should I inhale?”—perceptions, barriers, and drivers for medicinal cannabis use amongst Australian women with primary dysmenorrhoea: a qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(3):1536. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031536.

Stephen MJ, Chowdhury J, Tejada LA, Zanni R, Hadjiliadis D. Use of medical marijuana in cystic fibrosis patients. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2020;20(1):323.

Stillman M, Mallow M, Ransom T, Gustafson K, Bell A, Graves D. Attitudes toward and knowledge of medical cannabis among individuals with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord Ser Cases. 2019;5:6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-019-0151-6.

Storr M, Devlin S, Kaplan GG, Panaccione R, Andrews CN. Cannabis use provides symptom relief in patients with inflammatory bowel disease but is associated with worse disease prognosis in patients with Crohnʼs disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(3):472–80.

Sukrueangkul A, Phimha S, Panomai N, Laohasiriwong W, Sakphisutthikul C. Attitudes and beliefs of cancer patients demanding medical cannabis use in North Thailand. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2022;23(4):1309–14.

Sura KT, Kohman L, Huang D, Pasniciuc SV. Experience with medical marijuana for cancer patients in the palliative setting. Cureus. 2022. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.26406.

Tanco K, Dumlao D, Kreis R, Nguyen K, Dibaj S, Liu D, et al. Attitudes and beliefs about medical usefulness and legalization of marijuana among cancer patients in a legalized and a nonlegalized state. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(10):1213–20.

Taneja S, Guo Y, Slaven M, Lalani AK, Shaw E, Tajzler C, et al. The perceptions and beliefs of cannabis use among Canadian genitourinary cancer patients. CUAJ. 2021. https://doi.org/10.5489/cuaj.7197.

Victorson D, McMahon M, Horowitz B, Glickson S, Parker B, Mendoza-Temple L. Exploring cancer survivors’ attitudes, perceptions, and concerns about using medical cannabis for symptom and side effect management: a qualitative focus group study. Complement Ther Med. 2019;47: 102204.

Ware MA, Rueda S, Singer J, Kilby D. Cannabis use by persons living with HIV/AIDS: patterns and prevalence of use. J Can Ther. 2003;3(2):3–15.

Weiss MC, Hibbs JE, Buckley ME, Danese SR, Leitenberger A, Bollmann-Jenkins M, et al. A Coala-T-cannabis survey study of breast cancer patients’ use of cannabis before, during, and after treatment. Cancer. 2022;128(1):160–8.

Wilson A, Davis C. Attitudes of cancer patients to medicinal cannabis use: a qualitative study. Austr Social Work. 2022;75(2):192–204.

Zeiger JS, Silvers WS, Winders TA, Hart MK, Zeiger RS. Cannabis attitudes and patterns of use among followers of the allergy & asthma network. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;126(4):401-410.e1.

Zhou ES, Nayak MM, Chai PR, Braun IM. Cancer patient’s attitudes of using medicinal cannabis for sleep. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2022;40(3):397–403.

Acknowledgements

We would like to particularly thank Pamela Lipson for a linguistic revision of the manuscript.

Funding

Marie-Pascale Pomey has a Senior Career Award financed by the Quebec Health Research Fund (FRQS), the University of Montreal Hospital Research Centre (CRCHUM)and the Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux du Québec. This research was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada (MSSC)—Funding #: 02088-000.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: Pomey, M-P, Paquette, J., Jutras-Aswad, D., Ikene, D-L., Taguemout, M.; Data collection: Saadi, K., Paquette, J., Ikene, D-L., Taguemout, M.; Data analysis and interpretation: Paquette, J. Saadi, K.; Draft manuscript preparation: Paquette, J., Ikene, D-L., Taguemout, M. Saadi, K. All the authors revised and approved the final version of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study has received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee (21.309) of the University of Montreal Hospital Research Centre (CRCHUM).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Search strategies.

Additional file 2:

Extraction grid.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Pomey, MP., Jutras-Aswad, D., Paquette, J. et al. Perceptions and engagement of patients with chronic conditions on the use of medical cannabis: a scoping review. Eur J Med Res 29, 211 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-024-01803-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-024-01803-w