Abstract

Background

Respiratory mechanics monitoring provides useful information for guiding mechanical ventilation, but many measuring methods are inappropriate for awake patients. This study aimed to evaluate the accuracy of dynamic mechanics estimation using expiratory time constant (RCexp) calculation during noninvasive pressure support ventilation (PSV) with air leak in different lung models.

Methods

A Respironics V60 ventilator was connected to an active breathing simulator for modeling five profiles: normal adult, restrictive, mildly and severely obstructive, and mixed obstructive/restrictive. Inspiratory pressure support was adjusted to maintain tidal volumes (VT), achieving 5.0, 7.0, and 10.0 ml/kg body weight. PEEP was set at 5 cmH2O, and the back-up rate was 10 bpm. Measurements were conducted at system leaks of 25–28 L/min. RCexp was estimated from the ratio at 75% exhaled VT and flow rate, which was then used to determine respiratory system compliance (Crs) and airway resistance (Raw).

Results

In non-obstructive conditions (Raw ≤ 10 cmH2O/L/s), the Crs was overestimated in the PSV mode. Peak inspiratory and expiratory flow and VT increased with PS levels, as calculated Crs decreased. In passive breathing, the difference of Crs between different VT was no significant. Underestimations of inspiratory resistance and expiratory resistance were observed at VT of 5.0 ml/kg. The difference was minimal at VT of 7.0 ml/kg. During non-invasive PSV, the estimation of airway resistance with the RCexp method was accurately at VT of 7.0 ml/kg.

Conclusions

The difference between the calculated Crs and the preset value was influenced by the volume, status and inspiratory effort in spontaneously breathing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Mechanical ventilation is a lifesaving intervention that has become widely used in the management of critically ill patients [1, 2]. The exact settings of the ventilator must be adequately adjusted according to the patients’ conditions to optimize the patient outcomes and prevent ventilator-induced injury and complications [2, 3]. The analysis of individual respiratory mechanics is beneficial for guiding the ventilator setting under the conditions of lung-protective mechanical ventilation [4].

In the past 15 years, the focus on respiratory mechanics analysis changed from the static to the dynamic conditions [5]. “Static” or “quasi-static” conditions mean that the analysis of the respiratory mechanics is performed under conditions of zero airflow, which is typically carried out using an end-inspiration and an end-expiration pause [6]. “Dynamic” conditions mean that the measurement is performed under conditions of no flow interruption during mechanical ventilation [7]. The advantage of the dynamic analysis is that respiratory maneuvers such as zero-flow occlusion and the interruption of the patient spontaneous breathing are not required.

Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NPPV) is used in patients with mild to moderate respiratory failure, since relatively stable spontaneous breathing is necessary, and air leaks are always present when using a face mask [8]. Pressure support ventilation (PSV) is one of the most used modes of non-invasive ventilation, which also requires the patient’s breathing effort to trigger. Despite the wide use of PSV, the accurate estimation of the respiratory mechanics during PSV is still a problem, and the static methods are applied to PSV, since airflow is always present and variable both in inspiration and expiration [9, 10].

Recently, some dynamic approaches have been introduced, considerably refined by the improvement of static measurement, and addressing the need for accurate estimation of lung mechanics [11, 12]. One of the new continuous methods is based on estimating respiratory system compliance (Crs) and airway resistance (Raw), which do not depend on end-inspiratory occlusion. Al-Rawas et al. [13] proposed the expiratory time constant (RCexp) for the determination of Crs and total Raw. RCexp contains information about the mechanical properties of the respiratory system, but it still refinement, particularly under the condition of air leaks.

We hypothesized that real-time sampling of the respiratory data obtained from the inspiration and expiration phases would improve the precision of the estimation of the respiratory system mechanics. Hence, the purpose of this bench study was to evaluate the accuracy of dynamic mechanics estimation using RCexp calculation during PSV with air leak in different lung models.

Methods

Lung models

The ASL 5000 Breathing Simulator (IngMar Medical, Pittsburg, PA, USA) features a computerized lung simulator comprising a piston moving in a cylinder. The simulator is a single-compartment model [14]. Respiratory mechanics conditions were adjusted to simulate an adult patient (65–70 kg body weight) placed in the semi-recumbent position (inclination of 45°). Five respiratory mechanics conditions were preset: mildly obstructive (Raw = 10 cmH2O/L/s, static Crs = 50 mL/cmH2O, and rate = 15 breaths/min); severely obstructive (Raw = 20 cmH2O/L/s, static Crs = 50 mL/cmH2O, and rate = 15 breaths/min); restrictive (Raw = 10 cmH2O/L/s, static Crs = 25 mL/cmH2O, and rate = 30 breaths/min); mixed obstructive and restrictive (Raw = 20 cmH2O/L/s, static Crs = 25 mL/cmH2O, and rate = 15 breaths/min); and normal adult (Raw = 5 cmH2O/L/s, static Crs = 50 mL/cmH2O, and rate = 15 breaths/min). The inspiratory time was set at 0.8 s for the restrictive conditions and 1.6 s for the other conditions [15,16,17]. The patient’s inspiratory effort was −5 cmH2O for the normal, obstructive, and mixed obstructive/restrictive conditions and −10 cmH2O for the restrictive condition. Pressure reduction produced 300 ms following initiation of an obstructed inspiratory effort was −3.6 cmH2O. A semi-sinusoidal inspiratory waveform was chosen, with the rise and release times each of 50%, and an inspiratory hold time of 0%. The simulator integrates user-controlled leaks using a plateau exhalation valve (PEV). In the current study, air leak was controlled between 24 and 26 L/min with 20 cmH2O peak airway pressure [18]. The inspired oxygen fraction (FIO2) was maintained at 0.21.

The patient–mask interface was simulated using a mannequin head. Endotracheal tubes (inner diameter, 22 mm) placed in the mouth and nostrils directed the gas from the facemask to the simulator. An oro-nasal facemask without exhalation ports (BestFit™; Curative Medical Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) was fastened firmly to the mannequin head using standard straps. A leak flow below 1–2 L/min was obtained at 20 cmH2O positive pressure after PEV removal [20].

Ventilator settings

This bench study was performed using a dry circuit without a humidifier. First, five passive conditions with zero breathing frequency and zero inspiratory muscle pressure (Pmus) were simulated. A Hamilton C3 ventilator (Hamilton Medical AG, Bonaduz, Switzerland) was linked to the lung simulator without facemask and PEV. The ventilator was calibrated and configured in the volume-controlled ventilation (VCV) mode. Then, it was configured in the pressure-controlled ventilation (PCV) mode. Finally, active conditions with a spontaneous effort were simulated. A Respironics V60 Bilevel Ventilator (Philips, Best, The Netherlands) was also connected to the lung simulator via a 1.8-m-long single-use, single limb, corrugated circuit with facemask and PEV. The V60 ventilator was calibrated and configured in the PSV mode. The ventilator’s parameters were set according to respiratory mechanics profiles: positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP). The PC and PS levels were adjusted to obtain tidal volumes (VT), achieving 5.0, 7.0, and 10.0 ml/kg body weight outputted by the ventilator using a back-up respiratory rate of 10 breaths/min and maximal duration of the inspiratory phase of 2.0 s. The shorter inspiratory rise time was selected but avoiding overshoot [19, 20]. The trigger sensitivity and cycling criteria were auto-adjusted in the PSV mode (digital Auto-Trak™) [21].

Data collection

After baseline pressure stabilization, air leaks from the PEV were supplemented to the system, with ≥ 5 min allowed for ventilator/simulator synchronization. In the case of synchronization failure, sensitivity, and/or inspiratory effort were changed. If synchronization remained unachievable, the ventilator was regarded as unfit for assisted ventilation at that level of the leak. Upon stabilization, eight breaths were recorded at 1-min intervals. The offline assessment of all breaths was carried out with the software provided with the ASL 5000 Breathing Simulator.

In the inspiratory phase, peak inspiratory flow (PIF), end-inspiration pressure (EIP), inspiratory time (TI), expiratory tidal volume (VTE) were measured by the simulator. The peak expiratory flow (PEF) and total PEEP were sampled in the expiration phase.

The RCexp was estimated by the ratio between volume and flow at 75% of the expiratory VT (TEF75) [22]. The quasi-static two-point compliance of the respiratory system (Crs) was calculated as the ratio between VTE and driving pressure (ΔP). The driving pressure was calculated as the difference between EIP and total PEEP, measured at end-inspiration and end-expiration, respectively. Because subjects were ventilated in the pressure support mode (with exponential decay of inspiratory flow waveform), the inspiratory resistance (Rinsp) was estimated using Eq. 3, and the expiratory resistance (Rexp) was calculated using Eq. 4 [13, 23]:

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were presented as means ± standard deviations. The normality of the data was assessed by the Shapiro–Wilk test. Comparisons of variables at different settings were performed by one-way randomized block ANOVA. Statistical analysis was carried out with SPSS 19.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Two-tailed P < 0.01 was considered statistically significant. Differences between calculated values with RCexp method and preset values were expressed as the percentages of preset values. The smaller the error, the more clinically significant the parameter. The purpose of this study was to observe the error size, which should be optimally ≤ 10%.

Results

Measured airflow and airway pressure at different VT ventilation in the various models

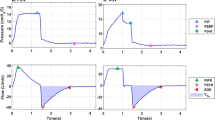

The results of the dynamic mechanics at different VT levels are summarized in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5. The V60 ventilator was able to adapt to the system leak (25–28 L/min) without adjustment. Increasing the PS and PC levels was associated with higher PIF and PEF and larger tidal volume. In all lung models, PIF was always higher than PEF in the PSV mode. PIF in the PSV mode was also higher than in the PCV model (Figs. 1 and 2). Compared with passive breathing, the driving pressure was much lower than in active breathing conditions at VT of 5.0 to 10.0 ml/kg.

Crs and RCexp at different VT ventilation in the various models

Crs and RCexp were calculated according to Eqs. 1 and 2, respectively, as described above, with PEEP kept constant at end-expiration. In the passive breathing conditions, the calculated Crs were close to the preset value, except in the severely obstructive model. When an inspiratory effort was present, the calculated Crs was always overestimated grossly at VT of 5.0–7.0 ml/kg in non-severely obstructive conditions (Raw ≤ 10 cmH2O/L•s), and the calculated value was decreased as VT increased (Fig. 3 and Tables 1, 2, and 4).

Comparisons of system compliance (Crs) in various models during controlled and assisted ventilatory mode. Normal adult (A), mildly obstructive (B), severely obstructive (C), restrictive (D), and mixed (E) models. Data are presented as mean ± SD. P < 0.01 vs. PSV for all pairwise comparisons. The dotted line represents the preset value of Crs

In the passive breathing condition, the calculation of RCexp in the PCV mode exceeded the value in the VCV mode (P < 0.01). During assisted ventilation, the calculated value was slightly affected by VT in all four lung disease models, and no difference was observed at different VT in the mixed obstructive and restrictive model (P = 0.403) (Fig. 4).

Comparisons of the expiratory time constant (RCexp) in various models during controlled and assisted ventilatory mode. Normal adult (A), mildly obstructive (B), severely obstructive (C), restrictive (D), and mixed (E) models are shown. Data are presented as mean ± SD. P < 0.01 vs. PSV for all pairwise comparisons

Estimated inspiratory and expiratory resistance at different VT ventilation in the various models

Rinsp and Rexp were calculated according to Eqs. 3 and 4. During assisted ventilation, Rinsp was underestimated at VT of 5.0 ml/kg in all five models. The calculated value generally increased with increasing VT. The estimated error might be minimal at VT of 7.0 ml/kg, regardless of the change of respiratory mechanics. In passive breathing, Rinsp was always overestimated despite the alteration of VT. Similar results were obtained for calculated Rexp. The difference between the calculated and preset values was reduced remarkably at VT of 7.0 ml/kg in the PSV model (Fig. 5).

Comparisons of inspiratory (Rinsp) and expiratory resistance (Rexp) in various models during the controlled and assisted ventilatory mode. Normal adult (A), mildly obstructive (B), severely obstructive (C), restrictive (D), and mixed (E) models are shown. Data are presented as mean ± SD. P < 0.01 vs. PSV for all pairwise comparisons. The dotted line represents the preset value of Raw

Discussion

Currently, static measurements are performed at end-inspiration and end-expiration occlusion, as provided by many mechanical ventilators, which is a standard and classic method, and the data represent the static mechanical properties of the respiratory system. The occlusion method should be fulfilled with no flow and a static tidal volume. It is essential that the patient is not allowed to force during static measurements, whether due to disease, sedation, or paralysis [24,25,26]. Furthermore, it is assumed that Crs is linear between end-inspiration and end-expiration [27, 28]. In reality, during assisted ventilation, an inspiratory effort always exists in spontaneously breathing patients. The change in airway pressure generated by Pmus mainly depends on diaphragm activity and the driving pressure output by the ventilator. Since Pmus varies with time and among individuals, sampling and analyzing such respiratory system mechanics is very difficult [29].

Dynamic estimations might assess the mechanical characteristics of the respiratory system during assisted ventilation with the variable gas flow. With recent advances in monitoring technology and sophisticated software, real-time estimation at the bedside is a helpful diagnostic tool for assisting therapeutic decisions and adjusting the ventilator settings [9, 30]. The least-square fitting (LSF) technique is one type of dynamic measurements. Recursive least squares (RLS) is a modified LSF technique that derives values for Crs and Raw by solving a linear regression equation in which Paw, VT, and flow measurements are multiple recorded times (up to 100–200 Hz) during the respiratory cycle [31].

Another dynamic estimation technique is based on RCexp calculation. RCexp contains information about the mechanical properties of the respiratory system (elastance and resistance) and is defined as the product of the total respiratory system compliance and expiratory resistance. RCexp is expressed in units of time (s), and 1 RCexp represents the time required for the respiratory system to reach 63% of its equilibrium value and is an indication of the time required for the lung to empty during exhalation [32, 33]. A study showed that Crs, Rinsp, and Rexp could be estimated in real-time using RCexp calculation and combined with some equations during mandatory controlled ventilation and assisted ventilation, such as PSV [13]. Čandik et al. [34] observed the relationship between RCexp and breathing cycle time (Tcycle) during PSV and provided the equation: Tcycle = 5.2625 × RCexp + 0.1242(R2 = 0.85). In this bench study, the pressure and flow datas were obtained by the sensors built in the ASL5000, and off-line analysis using some specical equations. The RCexp was calculated by the volume/flow ratio at 75% of the exhaled VT. During pressure support and PCV, the calculated RCexp value varied with tidal volume alteration in all lung models. Only in the severely obstructive condition, the difference of RCexp value between different tidal volume was not significant in the PSV mode (P > 0.05). Similarly, the calculations of Rinsp and Rexp were also affected by the VT in all lung conditions. The difference between the calculation and preset value was minimal at VT of 7.0 ml/kg.

During pressure-preset ventilation, such as PSV, the airway pressure waveform is rectangular, and the inspiratory flow varies; the dynamics of lung filling and emptying can be exactly described by exponential equations and is affected by ventilatory parameters and respiratory system characteristics [16]. The advantage of PSV is that the variable inspiratory flow can meet the patient’s demand and improve comfort. PSV must be triggered by the patient’s inspiratory effort. Usually, the patient’s effort is detected by a pressure trigger or a flow trigger. During non-invasive ventilation, the most used trigger mechanism is the flow shape-signal technique, which applies a mathematical model derived from the flow and pressure signals, with better tolerance and reduced trigger asynchrony [14, 35]. The dynamic approach was selected, because it requires neither special maneuvers nor particular flow patterns and does not rely on the amplitude and shape of inspiration effort (Pmus). In this bench study, the simulator was ventilated in the pressure support mode with exponential decay of inspiratory flow waveform. The driving pressure was calculated as EIP–PEEP, with EIP obtained at the end-inspiration phase after the inspiratory flow is deduced from the PIF. Crs calculation is restricted to the tidal volume and driving pressure [36]. Iotti et al. [37] found that calculated Crs could be affected by the PS levels. With low PS levels and high spontaneous breathing activity, calculated Crs was overestimated, while Raw was underestimated; similar Crs values were obtained at equal VT during PSV with mandatory controlled ventilation (CMV) at a constant flow. In this bench study, the lung simulator was set to simulate an adult with normal body weight (65–70 kg), considering Crs and Raw remained constant throughout any given breath. We demonstrated that the calculated Crs gradually decreased with increasing PS levels and VT. With normal–mild obstructive (Raw ≤ 10 cmH2O/L/s) and/or strong inhalation effort, the estimation of Crs always exceeded the preset value. This may be due to the patient’s spontaneous effort, rather than to the changes in VT. Only in the severely obstructive conditions, the patient’s breathing pattern was dependent upon the ventilator parameters setting, not on the effort. The difference of Crs between the calculated and preset values might be minimal at VT of 7.0 ml/kg.

The present study has some limitations. First, all tests were performed on the ASL 5000 Lung Simulator and under several typical lung mechanics setting. The one-compartment linear model was selected, which assumes that static Crs and Raw remain constant throughout the respiratory cycle. Intrinsic PEEP (auto-PEEP) was also not preset in this study. Nevertheless, it is clear that compliance depends on the volume status, and the resistance is both volume and flow-dependent [38]. The value of compliance throughout the inspiration changes with increasing airway pressure. Stahl et al. [39] found that compliance appears to decline at higher levels of inspiratory pressure during tidal breathing. The quasi-static compliance is increased until the airway pressure reaches 30 cmH2O; nevertheless, dynamic compliance is decreased when the airway pressure is above 15 cmH2O. Second, resistance changes with the level of flow through the tube on which it is being measured. The higher the flow through the resistive path, the higher the resistance in the path and vice versa. In this way, the information presented to the user represents the maximum resistance experienced by the patient during the phases of the breath. Third, an ICU ventilator (Hamilton C3) was used in this bench study to obtain the quasi-static respiratory mechanics with the occlusion method. During volume-controlled ventilation, the inspiratory flow was kept constant in the inspiration phase, and the circuit was airtight without the mask and accessories. Since the gas flow is always variable and air leaks are found during non-invasive ventilation, the dedicated NPPV ventilators (such as V60 bi-level ventilator) with especially designed electromagnetic valves and leak compensation algorithm exhibit more homogeneous behavior than ICU ventilators on patient–ventilator synchrony [40]. As a bench study, it is unclear if the scheme can be fully translated in a clinical setting such as rapid shallow breathing. Therefore, additional studies are needed to confirm our findings.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the application of the concept of RCexp to spontaneously breathing subjects is feasible. Using simple calculation equations, the estimation of respiratory mechanics could be accurately and continuously by adjusting the PS levels in spontaneously breathing patients. Different from the occlusion method, monitoring of the RCexp allows assessing the overall respiratory mechanics without interrupting the patient’s breathing flow. The estimated accuracy of the system compliance clearly depends on the volume status and inspiratory effort in spontaneous breathing patients, whereas resistance calculation error might be minimal at a VT of 7.0 ml/kg.

Availability of data and materials

The data sets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- NPPV:

-

Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation

- PCV:

-

Pressure-controlled ventilation

- PSV:

-

Pressure support ventilation

- VCV:

-

Volume-controlled ventilation

- PEV:

-

Plateau exhalation valve

- FIO2:

-

Inspired oxygen fraction

- PEEP:

-

Positive end-expiratory pressure

- VTE:

-

Expiratory tidal volume

- ΔP:

-

Driving pressure

- PIF:

-

Peak inspiratory flow

- PEF:

-

Peak expiratory flow

- TEF75:

-

The flow at 75% of the expiratory VT

- Crs:

-

Respiratory system compliance

- RCexp:

-

Expiratory time constant

- Rinsp:

-

Inspiratory airway resistance

- Rexp:

-

Expiratory airway resistance

- N.S:

-

Not significant

References

Walter K. Mechanical Ventilation. JAMA. 2021;326(14):1452. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.13084.

Pham T, Brochard LJ, Slutsky AS. Mechanical ventilation: state of the Art. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1382–400.

Beitler JR, Malhotra A, Thompson BT. Ventilator-induced Lung Injury. Clin Chest Med. 2016;37:633–46.

Gattinoni L, Eleonora C, Caironi P. Monitoring of pulmonary mechanics in acute respiratory distress syndrome to titrate therapy. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2005;11:252–8.

Stenqvist O, Odenstedt H, Lundin S. Dynamic respiratory mechanics in acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome: research or clinical tool? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2008;14:87–93.

Rossi A, Gottfried SB, Zocchi L, Higgs BD, Lennox S, Calverley PM, et al. Measurement of static compliance of the total respiratory system in patients with acute respiratory failure during mechanical ventilation. The effect of intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985;131:672–7.

Mols G, Priebe HJ, Guttmann J. Alveolar recruitment in acute lung injury. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96:156–66.

Akashiba T, Ishikawa Y, Ishihara H, Imanaka H, Ohi M, Ochiai R, et al. The Japanese respiratory society noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NPPV) guidelines (second revised edition). Respir Investig. 2017;55:83–92.

Zhao Z, Eger M, Handzsuj T, Ranieri VM, Appendini L, Micelli C, et al. Noninvasive method for measuring respiratory system compliance during pressure support ventilation. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2011;2011:3808–11.

Henderson WR, Sheel AW. Pulmonary mechanics during mechanical ventilation. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2012;180:162–72.

Lichtwarck-Aschoff M, Kessler V, Sjöstrand UH, Hedlund A, Mols G, Rubertsson S, et al. Static versus dynamic respiratory mechanics for setting the ventilator. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85:577–86.

Guttmann J. Analysis of respiratory mechanics during artificial ventilation. Biomed Tech (Berl). 1998;43:107–15.

Al-Rawas N, Banner MJ, Euliano NR, Tams CG, Brown J, Martin AD, et al. Expiratory time constant for determinations of plateau pressure, respiratory system compliance, and total resistance. Crit Care. 2013;17:R23.

Beloncle F, Akoumianaki E, Rittayamai N, Lyazidi A, Brochard L. Accuracy of delivered airway pressure and work of breathing estimation during proportional assist ventilation: a bench study. Ann Intensive Care. 2016;6:30.

Bosma KJ, Read BA, Bahrgard Nikoo MJ, Jones PM, Priestap FA, Lewis JF. A pilot randomized trial comparing weaning from mechanical ventilation on pressure support versus proportional assist ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:1098–108.

Marini JJ, Crooke PS 3rd, Truwit JD. Determinants and limits of pressure-preset ventilation: a mathematical model of pressure control. J Appl Physiol. 1985;1989(67):1081–92.

Hess DR. Ventilator waveforms and the physiology of pressure support ventilation. Respir Care. 2005;50:166–86.

Hill NS, Carlisle C, Kramer NR. Effect of a nonrebreathing exhalation valve on long-term nasal ventilation using a bilevel device. Chest. 2002;122:84–91.

Yamada Y, Du HL. Analysis of the mechanisms of expiratory asynchrony in pressure support ventilation: a mathematical approach. J Appl Physiol. 1985;2000(88):2143–50. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.2000.88.6.2143.

Chen Y, Yuan Y, Zhang H, Li F. Comparison of inspiratory effort, workload and cycling synchronization between non-invasive proportional-assist ventilation and pressure-support ventilation using different models of respiratory mechanics. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:9048–57 https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.914629 .

Vasconcelos Rdos S, Melo LH, Sales RP, Marinho LS, Deulefeu FC, Reis RC, et al. Effect of an automatic triggering and cycling system on comfort and patient-ventilator synchrony during pressure support ventilation. Respiration. 2013;86:497–503.

Brunner JX, Laubscher TP, Banner MJ, Iotti G, Braschi A. Simple method to measure total expiratory time constant based on the passive expiratory flow-volume curve. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:1117–22.

Arnal JM, Garnero A, Saoli M, Chatburn RL. Parameters for simulation of adult subjects during mechanical ventilation. Respir Care. 2018;63:158–68.

Macklem PT. The mechanics of breathing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:S88-94.

Barberis L, Manno E, Guérin C. Effect of end-inspiratory pause duration on plateau pressure in mechanically ventilated patients. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:130–4.

Lucangelo U, Bernabé F, Blanch L. Respiratory mechanics derived from signals in the ventilator circuit. Respir Care. 2005;50:55–65.

Henderson WR, Chen L, Amato MBP, Brochard LJ. Fifty years of research in ARDS. Respiratory mechanics in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:822–33.

Primiano FP Jr, Chatburn RL. Zen and the art of nomenclature maintenance: a revised approach to respiratory symbols and terminology. Respir Care. 2006;51:1458–70.

Amato MB, Barbas CS, Medeiros DM, Magaldi RB, Schettino GP, Lorenzi-Filho G, et al. Effect of a protective-ventilation strategy on mortality in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:347–54.

Zhao Z, Guttmann J, Möller K. Adaptive SLICE method: an enhanced method to determine nonlinear dynamic respiratory system mechanics. Physiol Meas. 2012;33:51–64.

Lauzon AM, Bates JH. Estimation of time-varying respiratory mechanical parameters by recursive least squares. J Appl Physiol. 1985;1991(71):1159–65.

Engel L. Dynamic distribution of gas flow. In: Macklem P, Mead J, editors. Comprehensive Physiology. Washington, D.C: American Physiologic Society; 1986.

Banner M, Lampotang S. Clinical use of inspiratory and expiratory waveforms. Toronto: BC Decker; 1988.

Čandik P, Rybár D, Depta F, Sabol F, Kolesár A, Galková K, et al. Relationship between dynamic expiratory time constant tau(edyn) and parameters of breathing cycle in pressure support ventilation mode. Physiol Res. 2018;67:875–9.

Poggi R, Appendini L, Polese G, Colombo R, Donner CF, Rossi A. Noninvasive proportional assist ventilation and pressure support ventilation during arm elevation in patients with chronic respiratory failure. A preliminary, physiologic study. Respir Med. 2006;100:972–9.

Lucangelo U, Bernabè F, Blanch L. Lung mechanics at the bedside: make it simple. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2007;13:64–72.

Iotti GA, Braschi A, Brunner JX, Smits T, Olivei M, Palo A, et al. Respiratory mechanics by least squares fitting in mechanically ventilated patients: applications during paralysis and during pressure support ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 1995;21:406–13.

Mead J, Collier C. Relation of volume history of lungs to respiratory mechanics in anesthetized dog. J Appl Physiol. 1959;14:669–78.

Stahl CA, Möller K, Schumann S, Kuhlen R, Sydow M, Putensen C, et al. Dynamic versus static respiratory mechanics in acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2090–8.

Carteaux G, Lyazidi A, Cordoba-Izquierdo A, Vignaux L, Jolliet P, Thille AW, et al. Patient-ventilator asynchrony during noninvasive ventilation: a bench and clinical study. Chest. 2012;142:367–76.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was funded by the “Star of Jiao Tong University” program of Shanghai Jiao Tong University Medical and Industrial Cross Research Fund Project [Grant No YG2019ZDB08]. The funder had the following involvement with the study: study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing the paper and decision to submit it for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CYQ conceptualization, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. YYY co-developed ideas for the study, directed clinical data collection, analyzed all data, and wrote all manuscript drafts, conceived all figures, and reviewed literature for reference material. HZ co-developed ideas for study, developed software used in the study, performed statistical analyses, co-derived equations used in the study, and contributed to preparation of the manuscript. FL performed statistical analyses and contributed to preparation of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Y., Yuan, Y., Zhang, H. et al. Accuracy of the estimations of respiratory mechanics using an expiratory time constant in passive and active breathing conditions: a bench study. Eur J Med Res 28, 195 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-023-01146-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-023-01146-y