Abstract

Background

Patients with congenital absence of the portal vein (CAPV) often suffer from additional medical complications such as hepatic tumors and cardiac malformations.

Case presentation

Congenital absence of the portal vein (CAPV) is a rare malformation. We present a case of a 16-year-old Chinese girl with CAPV with multiple pathology-proven hepatic focal nodular hyperplasias (FNHs) and ventricular septal defect (VSD). The CT and MRI features of this case are described, and previously reported cases are reviewed.

Conclusions

CAPV is a rare congenital anomaly and in such patients, clarifying the site of portosystemic shunts, liver disease, and other anomalies is critical for appropriate treatment selection and accurate prognosis determination. Close follow-up, including laboratory testing and radiologic imaging, is recommended for all CAPV patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In patients with congenital absence of the portal vein (CAPV), the mesenteric and splenic venous blood bypasses the liver through a congenital shunt vessel and drains into the systemic circulation, resulting in relatively poor perfusion of the liver [1]. To date, 78 such cases have been reported in the literature. Patients with CAPV often suffer from additional medical complications such as hepatic tumors and cardiac malformations. Here we report a case of CAPV with multiple hepatic focal nodular hyperplasias (FNH), which we studied with both computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Case presentation

A 16-year-old Chinese girl was admitted to Chinese PLA General Hospital with left upper abdominal pain, which she had experienced for 1 month. Physical examination revealed no abnormalities. Laboratory investigations revealed moderate elevations of total bile (43.9 μmol/L; normal 0 to 10 μmol/L) and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (89.5 U/L; normal 0 to 40 U/L), and mildly decreased serum albumin (33.2 g/L; normal 40 to 55 g/L). Serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), total bilirubin, and alkaline phosphatase levels were normal. Serologic markers for hepatitis B and C virus were negative. A chest x-ray showed normal pulmonary vascularity. The patient did not have any neurological manifestations of hepatic encephalopathy, and her blood ammonia level was 56 μmol/L (normal 18 to72 μmol/L).

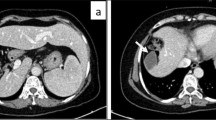

Precontrast abdominal CT revealed a large hypodense nodule in segment II (Figure 1A) and a small hypodense nodule in segment IV (Figure 1B) of the liver. Following intravenous administration of iodinated contrast, an additional lesion was seen in segment VI. Moderate enhancement was seen on arterial- and venous-phase images (Figure 1C,D). Precontrast MRI confirmed the presence of the three nodules in the liver. The largest one (segment II) measured 7.8 cm, and was markedly hyperintense on T1-weighted images (Figure 2A) and inhomogeneously hyperintense on T2-weighted images (Figure 2B). The other two lesions (segments IV and VI) measured 3.2 cm and 1.9 cm, respectively, and were heterogeneously hypointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images. After intravenous injection of gadopentetate dimeglumine (Gd-DTPA, Magnevist; Schering AG, Berlin, Germany), all three lesions showed strong enhancement on arterial phase images. On portal-venous phase images, these lesions were moderately hyperintense compared with normal liver parenchyma due to washout of contrast agent, while on delayed-phase images, areas of delayed enhancement were seen in all three lesions (Figure 2C,D). Based on these CT and MRI findings, we diagnosed this case as multiple FNH.

Abdominal precontrast computed tomography (CT) show lesions in segment II and IV. A and B show a large hypodense nodule (white arrow) in segment II and a small hypodense nodule (black arrowhead) in segment IV of the liver. The postcontrast CT images (C and D) show heterogeneously moderate enhancement of three lesions (white arrow, and black and white arrowheads) on arterial phase images. The intrahepatic portal vein was absent (white curved arrow).

Abdominal precontrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) show lesions in segment II. Most of the tumor in segment II has heterogeneously high signal intensity on both fat suppressed T2-weighted images (A, white arrow) and T1-weighted images (B, white arrow). On delayed-phase images after gadopentetate dimeglumine administration, central delayed enhancement was noted in all three tumors (C and D, white arrowheads).

During the radiologic workup of the patient, including both CT and MRI, no intrahepatic portal vein was seen. After joining of the middle and left hepatic veins, the portal trunk drained directly into the inferior vena cava (IVC) just below the level of the right atrium (Figure 3A,B). These vascular abnormalities were not identified prior to the hepatic surgery.

Abdominal precontrast computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The portal trunk drains directly into the inferior vena cava (IVC) just below the level of the right atrium, shown on both postcontrast computed tomography (CT) (A) and T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (B). White arrowhead = IVC; white arrow = portal trunk.

Five days later, the patient underwent resection of the three hepatic tumors. During intraoperative examination, intrahepatic portal branches were not apparent. The largest lesion (segment II) protruded out of the liver and was encapsulated within an intact capsule with rich subcapsular vessels (Figure 4A). All three lesions were completely removed. The gross pathologic investigation from one lesion (segment IV) revealed multiple nodules in the capsule (Figure 4B). Microscopically, all three lesions comprised nodules of hepatocytes separated by fibrous septa containing numerous dystrophic arteries, proliferated bile ducts, and lymphocytic infiltration. The diagnosis of multiple FNH was confirmed; however, the histologic features of the two smaller FNH lesions (segments IV and VI) and the larger FNH lesion (segment II) differed. Aside from the lack of veins, the two smaller FNH lesions were characteristic of classic FNH: (a) abnormal nodular architecture, (b) radiating fibrous septa originating from a central scar, (c) malformed arteries, and (d) bile duct proliferation (Figure 5A,B). The larger FNH lesion (segment II) showed less central scar and fibrous septa and, more importantly, contained substantial sinusoidal dilatation, consistent with telangiectatic FNH (Figure 6).

Histological features of the classic focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) in segment IV. The tumor was subdivided into nodules by fibrous septa (A, white arrowhead) originating from a central scar (A, white arrow). The malformed arteries (B, black arrow) and bile ductular proliferation (B, black arrowhead) was detected. No vein was found. Hematoxylin & eosin, A × 40; B × 100.

Histological features of the telangiectatic focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) in segment II. The lesion contained fewer septa and no central scar. In a few areas, the FNH showed a short septum containing a small number of malformed arteries (A, black arrow) and some bile ductular proliferation (A, black arrowhead). Arteries were embedded in extracellular matrix with inflammatory cells (B). Obvious sinusoidal dilatation (C) and peliosis (D) were observed. Hematoxylin and eosin, A 40X; B 100X; C 100X; D 100X.

Following surgery, liver ultrasonography (US) confirmed the CAPV and the presence of a portosystemic shunt, which fed directly into the IVC. Additionally, a ventricular septal defect (VSD) was observed using US.

Prior to discharge, the patient underwent an additional MRI with gadobenate dimeglumine (Gd-BOPTA, MultiHance; Bracco Imaging SpA, Milan, Italy), and additional hepatic nodules were found on delayed hepatobiliary-phase images obtained at one hour after contrast administration (Figure 7). These lesions were not seen on the CT examination or the MRI examination performed with gadopentetate dimeglumine.

Discussion

Congenital absence of the portal vein is a rare malformation in which mesenteric and splenic venous flow bypasses the liver and drains into various sites in the systemic venous system via an extrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Girls are more commonly affected than boys, and the clinical presentation is diverse [2]. CAPV may be associated with other congenital cardiac, skeletal, or visceral anomalies [2]. The diagnosis of CAPV is readily made by US, CT, and MRI [2]-[4].

Embryologically, the portal vein arises from the vitelline venous system between the 4th and 10th week of gestation [1],[5]. The intrahepatic portal vein originates from the superior link between the right and left vitelline veins; however, the extrahepatic portal vein arises from selective involution of the caudal part of the right and left vitelline veins [6]. Abnormal involution can lead to a preduodenal, prebiliary, or duplicated portal vein. Excessive involution can lead to complete or partial absence of the portal system [6]. As a result, mesenteric and splenic venous blood drains into renal veins, hepatic veins, or directly into the IVC, resulting in poor perfusion of the liver [2],[7],[8]. CAPV is often associated with hepatic tumors. The most common hepatic tumors reported were focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH). Other reported tumors included hepatoblastoma, hepatic adenoma, hepatocellular carcinoma and hemangioma.

To the best of our knowledge, a total 78 patients with CAPV have been described in the literature. The youngest was a fetus and the oldest was 64 years of age at the time of diagnosis [9],[10]. The majority of CAPV patients were children (53/78, 67.9%) and female (53/78, 67.9%). The first case of portosystemic anomaly with congenital diversion of portal blood away from the liver was reported by Abernethy in 1793 [11]. Morgan et al.[12] defined complete portosystemic shunts not perfusing the liver via the portal vein as type I, and partial shunts with minimal portal perfusion to the liver as type II. Type I CAPV is further subclassified into types Ia and Ib based on the anatomy of the portal vein: in type Ia, the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) and splenic vein (SV) are not united to constitute a confluence; in type Ib, the SMV and SV join to form a common trunk. Whereas in type Ia the SMV and SV drain individually into the IVC, SMV, or renal vein [13]-[15], in type Ib the confluence trunk of the splenic and mesenteric vein usually drains into the suprarenal or suprahepatic IVC [3],[16], or alternatively, it may flow into the hepatic vein, right atrium, iliac vein, inferior mesenteric vein, or renal vein [17],[18].

In a review of the 78 cases of CAPV in the literature, we found that type Ib is more common than type Ia (65.4% versus 30.8%, respectively). In terms of gender, both types occur predominantly in females (type 1a: 73.8%; type 1b: 73.9%). The case described here was type Ib: the SMV and SV united to form a portal trunk, joining the middle and left hepatic veins, and draining into the IVC without passing through the liver.

Congenital absence of the portal vein with a complete loss of portal perfusion leads to developmental and functional alterations that predispose the liver to focal or diffuse hyperplastic or dysplastic changes. These conditions lead to an increased incidence of hepatic tumors or tumor-like conditions [1]. Of the 78 reported cases of CAPV, 34 had hepatic tumors. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) was found in two cases [6],[19], hepatoblastoma in three cases [14],[20],[21], adenoma in five cases [13],[22]-[25], nodular regenerative hyperplasia (NRH) in five cases [16],[26]-[28], and pathologically unconfirmed tumors in four cases [3],[7],[29],[30]. However, focal nodular hyperplasia(FNH) was the most common hepatic tumor in patients with CAPV. Fifteen of the thirty-four reported cases with hepatic tumors involved FNH (Table 1), with four comprising solitary lesions [31]-[34], nine with multiple lesions [4],[5],[35]-[40], and one with an FNH lesion accompanied by additional tumors (HCC and adenoma) [41]. FNH and adenomas with a high risk of malignant transformation to HCC or hepatoblastoma [1]. Additionally, one reported case indicates a transformation from FNH to HCC in an adult patient with CAPV [42].

Pathological investigation revealed one of the lesions to be telangiectatic FNH. The telangiectatic FNH lesion presented no central scar, fewer fibrous septa, and substantial sinusoidal dilatation. On T1-weighted images, the telangiectatic FNH showed obvious hyperintensity, which differed from the signal typically seen with classic FNH. These findings are consistent with a previous study by Attal et al. [43], who found that telangiectatic FNH lesions lack a central scar and tend to be hyperintense on T1-weighted images due to sinusoidal dilatation.

In a review of the fifteen cases of CAPV with hepatic FNH, MRI was used in nine cases. In five of these eight cases, lesions were hyperintense on T1-weighted images [4],[5],[31],[37],[38],[40] and dilated sinusoids was seen histologically in 1 case. We suspect that some of these FNH lesions may have been telangiectatic and that the increased arterial hepatic flow by the hypertrophied hepatic artery may have played a role in their development.

Notably, delayed hepatobiliary phase MR imaging of the liver with gadobenate dimeglumine after surgery revealed numerous residual hepatic nodules not seen with gadopentetate dimeglumine. Given that delayed hepatobiliary phase MRI with gadobenate dimeglumine is known to improve the detection and characterization of FNH [44],[45], we believe that these nodules most likely represented additional FNH lesions.

Because CAPV and cardiac malformations may result from a similar embryogenic insult, cardiac malformations are frequently observed in patients with CAPV, and may help compensate for the congestive effect of the portal vein in these patients. Skeletal abnormalities including scoliosis, hemivertebrae [26],[34], and Goldenhar’s syndrome (oculo-auriculo-vertebral dysplasia) have also been described previously [14],[33]. The majority of congenital cardiac abnormalities seen in CAPV patients are ventricular septal defects (VSD), atrial septal defects (ASD), open foramen ovale, and patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) [7],[46]-[48]. The patient described here suffered from VSD, which was confirmed by US.

The majority of patients with CAPV have no signs or symptoms of portosystemic encephalopathy and only slightly abnormal liver function tests. Slight liver dysfunction was found in 41 patients, in spite of hyperammonemia being described in 11 patients and pulmonary hypertension (PA) in six patients. Our patient had slightly abnormal liver function, normal blood ammonia, and no encephalopathy. Wakamato et al. [31] suggested that the majority of patients with CAPV are not old enough to have portosystemic encephalopathy when described in the literature; nevertheless, the impact of portosystemic shunt on the central nervous system is serious, and its clinical potential should be considered in children with CAPV.

In general, US, CT, and MRI can all confirm the absence of the portal vein and visualize the portosystemic shunt. However, the vascular anomaly was not detected prior to surgery in this case. The use of US with echo-color Doppler may have been advantageous for depiction of the portal venous system and aberrant shunting. It is important to evaluate coexisting abnormalities, particularly hepatic tumors, with US, CT, and MRI. Although all three examination methods can be used as imaging tools in assessing coexisting hepatic tumors, delayed phase postcontrast MRI imaging with gadobenate dimeglumine may be the most sensitive for detection of small FNH lesions.

There are two treatment options available for patients with CAPV: close follow-up or liver transplantation. Close follow-up may be appropriate for patients with no signs or symptoms, or in those with only slight liver dysfunction. However, liver transplantation is indicated for patients with symptomatic CAPV refractory to medical treatment, especially those with associated hyperammonemia, portosystemic encephalopathy, hepatopulmonary syndrome (HPS), or hepatic malignant tumors [49]-[52].

Conclusions

In conclusion, we describe a patient with CAPV, and typical and atypical (telangiectatic) FNH. This patient displayed slight liver dysfunction and cardiac anomaly. CAPV is a rare congenital anomaly and in such patients, clarifying the site of portosystemic shunts, liver disease, and other anomalies is critical for appropriate treatment selection and accurate prognosis determination. In addition, we describe the pathoradiologic features of FNH on the delayed phase of imaging with hepatobiliary-specific MRI contrast agents. Close follow-up, including laboratory testing and radiologic imaging, is recommended for all CAPV patients.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this Case Report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

- CAPV:

-

congenital absence of the portal vein

- CT:

-

computed tomography

- FNHs:

-

focal nodular hyperplasias

- HCC:

-

hepatocellular carcinoma

- IVC:

-

inferior vena cava

- MRI:

-

magnetic resonance imaging

- NRH:

-

nodular regenerative hyperplasia

- SMV:

-

superior mesenteric vein

- SV:

-

splenic vein

- US:

-

ultrasonography

- VSD:

-

ventricular septal defect

References

Hu GH, Shen LG, Yang J, Mei JH, Zhu YF: Insight into congenital absence of the portal vein: is it rare? World J Gastroenterol 2008, 14: 5969–5979. Review 10.3748/wjg.14.5969

Goo HW: Extrahepatic portosystemic shunt in congenital absence of the portal vein depicted by time-resolved contrast-enhanced MR angiography. Pediatr Radiol 2007, 37: 706–709. 10.1007/s00247-007-0475-4

Maekawa S, Suzuki T, Mori K, Ichii O, Kanda K, Tai M, Ochiai H, Ejiri Y, Wakatsuki S, Takagi T, Ohira H, Tashiro M, Otsuki M: Congenital absence of the portal vein in an adult woman with liver tumor. Nippon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi 2007, 104: 1504–1511.

Turkbey B, Karcaaltincaba M, Demir H, Akcoren Z, Yuce A: Multiple hyperplastic nodules in the liver with congenital absence of portal vein: MRI findings. Pediatr Radiol 2006, 36: 445–448. 10.1007/s00247-005-0103-0

De Gaetano AM, Gui B, Macis G, Manfredi R, Di Stasi C, Manfredi R, Di Stasi C: Congenital absence of the portal vein associated with focal nodular hyperplasia in the liver in an adult woman: imaging and review of the literature. Abdom Imaging 2004, 29: 455–459. Review 10.1007/s00261-003-0131-x

Joyce AD, Howard ER: Rare congenital anomaly of the portal vein. Br J Surg 1988, 75: 1038–1039. 10.1002/bjs.1800751028

Noe JA, Pittman HC, Burton EM: Congenital absence of the portal vein in a child with Turner syndrome. Pediatr Radiol 2006, 36: 566–568. 10.1007/s00247-006-0169-3

Hino T, Hayashida A, Okahashi N, Wada N, Watanabe N, Obase K, Neishi Y, Kawamoto T, Okura H, Yoshida K: Portopulmonary hypertension associated with congenital absence of the portal vein treated with bosentan. Intern Med 2009, 48: 597–600. 10.2169/internalmedicine.48.1715

Venkat-Raman N, Murphy KW, Ghaus K, Teoh TG, Higham JM, Carvalho JS: Congenital absence of portal vein in the fetus: a case report. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2001, 17: 71–75. 10.1046/j.1469-0705.2001.00312.x

Le Borgne J, Paineau J, Hamy A, Dupas B, Lerat F, Raoul S: Interruption of the inferior vena cava with azygos termination associated with congenital absence of portal vein. Surg Radiol Anat 2000, 22: 197–202. 10.1007/s00276-000-0197-x

Abernethy J: Account of two instances of uncommon formation in the viscera of the human body. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 1973, 83: 295–299.

Morgan G, Superina R: Congenital absence of the portal vein: two cases and a proposed classification system for portasystemic vascular anomalies. J Pediatr Surg 1994, 29: 1239–1241. 10.1016/0022-3468(94)90812-5

Nakasaki H, Tanaka Y, Ohta M, Kanemoto T, Mitomi T, Iwata Y, Ozawa A: Congenital absence of the portal vein. Ann Surg 1989, 210: 190–193. 10.1097/00000658-198908000-00009

Barton JW III, Keller MS: Liver transplantation for hepatoblastoma in a child with congenital absence of the portal vein. Pediatr Radiol 1989, 20: 113–114. 10.1007/BF02010653

Kim SZ, Marz PL, Laor T, Teitelbaum J, Jonas MM, Levy HL: Elevated galactose in newborn screening due to congenital absence of the portal vein. Eur J Pediatr 1998, 157: 608–609. 10.1007/s004310050892

Peker A, Ucar T, Kuloglu Z, Ceyhan K, Tutar E, Fitoz S: Congenital absence of portal vein associated with nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the liver and pulmonary hypertension. Clin Imaging 2009, 33: 322–325. 10.1016/j.clinimag.2008.12.011

Tsutsui M, Sugahara S, Motosuneya T, Wada H, Fukuda I, Umeda E, Kazama T: Anesthetic management of a child with Costello syndrome complicated by congenital absence of the portal vein: a case report. Paediatr Anaesth 2009, 19: 714–715. 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2009.03050.x

Kasahara M, Nakagawa A, Sakamoto S, Tanaka H, Shigeta T, Fukuda A, Nosaka S, Matsui A: Living donor liver transplantation for congenital absence of the portal vein with situs inversus. Liver Transpl 2009, 15: 1641–1643. 10.1002/lt.21839

Lundstedt C, Lindell G, Tranberg KG, Svartholm E: Congenital absence of the intrahepatic portion of the portal vein in an adult male resected for hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur Radiol 2001, 11: 2228–2231. Review 10.1007/s003300100833

Marois D, van Heerden JA, Carpenter HA, Sheedy PF 2nd: Congenital absence of the portal vein. Mayo Clin Proc 1979, 54: 55–59.

Kawano S, Hasegawa S, Urushihara N, Okazaki T, Yoshida A, Kusafuka J, Mimaya J, Horikoshi Y, Aoki K, Hamazaki M: Hepatoblastoma with congenital absence of the portal vein - a case report. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2007, 17: 292–294. 10.1055/s-2007-965448

Kamiya S, Taniguchi I, Yamamoto T, Sawamura S, Kai M, Ohnishi N, Tsuda M, Yamamura M, Nakasaki H, Yokoyama S: Analysis of intestinal flora of a patient with congenital absence of the portal vein. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 1993, 7: 73–80. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1993.tb00384.x

Wojcicki M, Haagsma EB, Gouw AS, Slooff MJ, Porte RJ: Orthotopic liver transplantation for portosystemic encephalopathy in an adult with congenital absence of the portal vein. Liver Transpl 2004, 10: 1203–1207. 10.1002/lt.20170

Tateishi Y, Furuya M, Kondo F, Torii I, Nojiri K, Tanaka Y, Umeda S, Okudela K, Inayama Y, Endo I, Ohashi K: Hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 α inactivatedhepatocellular adenomas in patient with congenital absence of the portal vein: a case report. Pathol Int 2013, 63: 358–363. 10.1111/pin.12072

Asran MK, Loyer EM, Kaur H, Choi H: Case 177: Congenital absence of the portal vein with hepatic adenomatosis. Radiology 2012, 262: 364–367. 10.1148/radiol.11102046

Grazioli L, Alberti D, Olivetti L, Rigamonti W, Codazzi F, Matricardi L, Fugazzola C, Chiesa A: Congenital absence of portal vein with nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the liver. Eur Radiol 2000, 10: 820–825. 10.1007/s003300051012

Takeichi T, Okajima H, Suda H, Hayashida S, Iwasaki H, Ramirez MZ, Ueno M, Asonuma K, Inomata Y: Living domino liver transplantation in an adult with congenital absence of portal vein. Liver Transpl 2005, 11: 1285–1288. 10.1002/lt.20561

Tsuji K, Naoki K, Tachiyama Y, Fukumoto A, Ishida Y, Kuwabara T, Sumida T, Tatsugami M, Nagata S, Ohgoshi H, Uraki S, Hidaka T, Akagi Y, Ishine M, Saeki S, Chayama K: A case of congenital absence of the portal vein. Hepatol Res 2005, 31: 43–47. 10.1016/j.hepres.2004.11.006

Takagaki K, Kodaira M, Kuriyama S, Isogai Y, Nogaki A, Ichikawa N, Kajimura M: Congenital absence of the portal vein complicating hepatic tumors. Intern Med 2004, 43: 194–198. 10.2169/internalmedicine.43.194

Cheung KM, Lee CY, Wong CT, Chan AK: Congenital absence of portal vein presenting as hepatopulmonary syndrome. J Paediatr Child Health 2005, 41: 72–75. Review 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2005.00542.x

Wakamoto H, Manabe K, Kobayashi H, Hayashi M: Subclinical portal-systemic encephalopathy in a child with congenital absence of the portal vein. Brain Dev 1999, 21: 425–428. 10.1016/S0387-7604(99)00049-2

Guariso G, Fiorio S, Altavilla G, Gamba PG, Toffolutti T, Chiesura-Corona M, Tedeschi U, Zancan L: Congenital absence of the portal vein associated with focal nodular hyperplasia of the liver and cystic dysplasia of the kidney. Eur J Pediatr 1998, 157: 287–290. 10.1007/s004310050812

Morse SS, Taylor KJ, Strauss EB, Ramirez E, Seashore JH: Congenital absence of the portal vein in oculoauriculovertebral dysplasia (Goldenhar syndrome). Pediatr Radiol 1986, 16: 437–439. 10.1007/BF02386831

Matsuoka Y, Ohtomo K, Okubo T, Nishikawa J, Mine T, Ohno S: Congenital absence of the portal vein. Gastrointest Radiol 1992, 17: 31–33. Review 10.1007/BF01888504

Ringe K, Schirg E, Melter M, Flemming P, Ringe B, Becker T, Galanski M: Congenital absence of the portal vein (CAPV). Two cases of Abernethy malformation type 1 and review of the literature. Radiologe 2008, 48: 493–502. 10.1007/s00117-007-1561-1

Schmidt S, Saint-Paul MC, Anty R, Bruneton JN, Gugenheim J, Chevallier P: Multiple focal nodular hyperplasia of the liver associated with congenital absence of the portal vein. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2006, 30: 310–313. 10.1016/S0399-8320(06)73172-4

Tanaka Y, Takayanagi M, Shiratori Y, Imai Y, Obi S, Tateishi R, Kanda M, Fujishima T, Akamatsu M, Koike Y, Hamamura K, Teratani T, Ishikawa T, Shiina S, Kojiro M, Omata M: Congenital absence of portal vein with multiple hyperplastic nodular lesions in the liver. J Gastroenterol 2003, 38: 288–294. 10.1007/s005350300050

Kinjo T, Aoki H, Sunagawa H, Kinjo S, Muto Y: Congenital absence of the portal vein associated with focal nodular hyperplasia of the liver and congenital choledochal cyst: a case report. J Pediatr Surg 2001, 36: 622–625. 10.1053/jpsu.2001.22303

Motoori S, Shinozaki M, Goto N, Kondo F: Case report: congenital absence of the portal vein associated with nodular hyperplasia in the liver. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1997, 12: 639–643. 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1997.tb00527.x

Chandler TM, Heran MK, Chang SD, Parvez A, Harris AC: Multiple focal nodular hyperplasia lesions of the liver associated with congenital absence of the portal vein. Magn Reson Imaging 2011, 29: 881–886. 10.1016/j.mri.2011.03.001

Morotti RA, Killackey M, Shneider BL, Repucci A, Emre S, Thung SN: Hepatocellular carcinoma and congenital absence of the portal vein in a child receiving growth hormone therapy for turner syndrome. Semin Liver Dis 2007, 27: 427–431. 10.1055/s-2007-991518

Scheuermann U, Foltys D, Otto G: Focal nodular hyperplasia precedes hepatocellular carcinoma in an adult with congenital absence of the portal vein. Transpl Int 2012, 25: e67-e68. 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2012.01454.x

Attal P, Vilgrain V, Brancatelli G, Paradis V, Terris B, Belghiti J, Taouli B, Menu Y: Telangiectatic focal nodular hyperplasia: US, CT, and MR imaging findings with histopathologic correlation in 13 cases. Radiology 2003, 228: 465–472. 10.1148/radiol.2282020040

Grazioli L, Morana G, Federle MP, Brancatelli G, Testoni M, Kirchin MA, Menni K, Olivetti L, Nicoli N, Procacci C: Focal nodular hyperplasia: morphological and functional information from MR imaging with gadobenate dimeglumine. Radiology 2001, 221: 731–739. 10.1148/radiol.2213010139

Grazioli L, Morana G, Kirchin MA, Schneider G: Accurate differentiation of focal nodular hyperplasia from hepatic adenoma at gadobenate dimeglumine – enhanced MR imaging: prospective study. Radiology 2005, 236: 166–177. 10.1148/radiol.2361040338

Laverdiere JT, Laor T, Benacerraf B: Congenital absence of the portal vein: case report and MR demonstration. Pediatr Radiol 1995, 25: 52–53. 10.1007/BF02020848

Ohnishi Y, Ueda M, Doi H, Kasahara M, Haga H, Kamei H, Ogawa K, Ogura Y, Yoshitoshi EY, Tanaka K: Successful liver transplantation for congenital absence of the portal vein complicated by intrapulmonary shunt and brain abscess. J Pediatr Surg 2005, 40: e1-e3. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.02.011

Gocmen R, Akhan O, Talim B: Congenital absence of the portal vein associated with congenital hepatic fibrosis. Pediatr Radiol 2007, 37: 920–924. 10.1007/s00247-007-0533-y

Sanada Y, Mizuta K, Kawano Y, Egami S, Hayashida M, Wakiya T, Mori M, Hishikawa S, Morishima K, Fujiwara T, Sakuma Y, Hyodo M, Yasuda Y, Kobayashi E, Kawarasaki H: Living donor liver transplantation for congenital absence of the portal vein. Transplant Proc 2009, 41: 4214–4219. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.08.080

Sumida W, Kaneko K, Ogura Y, Tainaka T, Ono Y, Seo T, Kiuchi T, Ando H: Living donor liver transplantation for congenital absence of the portal vein in a child with cardiac failure. J Pediatr Surg 2006, 41: e9-e12. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.07.014

Uchida H, Sakamoto S, Shigeta T, Hamano I, Kanazawa H, Fukuda A, Karaki C, Nakazawa A, Kasahara M: Living donor liver transplantation with renoportal anastomosis for a patient with congenital absence of the portal vein. Case Rep Surg 2012, 2012: 670289.

Matsuura T, Soejima Y, Taguchi T: Auxiliary partial orthotopic living donorliver transplantation with a small-for-size graft for congenital absence of the portal vein. Liver Transpl 2010, 16: 1437–1439. 10.1002/lt.22179

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contribution of Dr Huiyi Ye for his insight. We thank Dr Xiaojin Zhang for her technical assistance. This study was supported by grants from The Project of Capital Special Health Industry Development Research (2011-5001-05).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors participated in the preparation of the manuscript. KZ collected the case information and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, K., Wang, Q., Wang, H. et al. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of multiple focal nodular hyperplasias of the liver with congenital absence of the portal vein in a Chinese girl: case report and review of the literature. Eur J Med Res 19, 63 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-014-0063-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-014-0063-7