Abstract

Biochar, widely recognized for its capacity to counteract climate change impacts, has demonstrated substantial benefits in agricultural ecosystems. Nevertheless, empirical studies exploring its efficacy during climatic aberrations such as heavy rainfall are limited. This study investigated the effects of compost and biochar addition on corn growth attributes, yield, and soil CO2 and N2O fluxes under heavy rain (exceeding 5-yr average) and waterlogging conditions. Here, treatments included compost (CP, 7.6 t ha−1); rice husk biochar (RB, 7.6 t ha−1); wood biochar (WB, 7.6 t ha−1); and control (Cn). Under high rainfall and waterlogging, the CP treatment manifested a pronounced enhancement in corn biomass and productivity, exceeding biomass and productivity of Cn treatment by 12.6 and 32.2%, RB treatment by 120 and 195%, and WB treatment by 86.1 and 111%, respectively. Corn yield increased in the order: CP > Cn > WB > RB. Intriguingly, negligible disparity occurred between the RB and WB treatments in straw yield, grain yield, grain index, and corn productivity but both treatments recorded distinctively lower values than CP treatment. Also, the CO2 and N2O fluxes remained largely similar for two biochar treatments but lower than CP treatment. Overall, CP increased corn yield, straw, and grain yield whereas biochars reduced N2O flux during waterlogging. Although derived from a short-term experimental window, these pivotal findings furnish invaluable insights for devising soil amendments for yield and environmental benefits in contexts of extreme climatic perturbations. Our findings offer a robust foundation for refining nutrient management strategies confronted with waterlogging challenges, but long-term studies are necessary for definitive conclusions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change, an undeniable challenge of our era, looms large, casting long shadows on the intricate tapestry of global ecosystems. Intensified by the relentless surge in anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [1] primarily due to industrialization, its specter continues to grow more ominous with each passing day [2].

A poignant concern echoing in agrarian circles is the dwindling water availability, due to climatic change. This paucity not only wields influence over crop yield dynamics but has also spurred global discourse on strategies to counter the resultant drought stress [3,4,5,6]. Drought could unleash a cascade of disruptions in plants, impeding the very lifecycle of crops from germination to harvest [7, 8]. Indeed, climate change and extreme weather events impact agriculture [9] by modifying precipitation patterns, frequency, and intensity. On the other hand, heavy rainfall and waterlogging are very common in irrigated areas causing crop damage, insect-pest infestation, and yield loss [10].

Researchers across diverse sectors are converging their efforts in crop and nutrient management strategies to curtail emissions and adapt agriculture to climatic impacts [11, 12]. As such, soil amendments like biochar and compost could be a means of sequestering carbon [13] while reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, improving soil health, and increasing crop productivity [14,15,16,17]. However, their effects under waterlogging conditions remain largely unknown.

Waterlogging is the inundation of soil surface causing abiotic stress. It constrains crop growth and productivity by imperiling soil health and jeopardizing yields [10, 18, 19]. It reduces oxygen availability in soils, thereby affecting root respiration. This further portends challenges for root and shoot growth and plant survival, depending on the growth stage and waterlogging duration. Organic amendments such as compost and biochar have ignited burgeoning interest for its potential role in elevating soil health and bolstering crop productivity. Agegnehu et al. [20] reported 10–29% increase in corn grain yield with organic amendments (compost, biochar) and lower N2O emission over time with biochar in North Queensland, Australia. Biochar generally improves soil porosity, aggregate stability, and infiltration depending upon application rates and biochar properties; thereby reducing raindrop impacts [21]. While a plethora of research delves into biochar’s prowess in drought management [22, 23], there is a palpable dearth in studies exploring its impact in conditions marked by excessive rainfall. Further, studies on waterlogging conditions are mainly available from rice crops. For example, in waterlogged paddy fields, biochar derived from rice straw are reported to increase rice yield and N retention [24, 25], and reduce CH4 and CO2 emission [26]. However, biochar and compost impacts on waterlogged upland soils with corn are still poorly understood. Therefore, our study aims to understand the influence of biochar and compost on upland corn’s growth attributes, yield, and soil CO2 and N2O fluxes in waterlogged conditions. A complete block design was established with four treatments: compost (CP, 7.6 t ha−1); rice husk biochar (RB, 7.6 t ha−1); wood biochar (WB, 7.6 t ha−1); and control (Cn), each replicated three times. CO2 and N2O fluxes were continuously monitored during cropping season while corn yield characteristics such as height, leaf and stem weight, biomass productivity, total weight, yield, kernel weight, and productivity were recorded after harvest. Our quest is to unfurl a nuanced, quantitative understanding of biochar’s efficacy in these challenging scenarios, offering insights that could potentially minimize GHG and improve agricultural sustainability.

Materials and methods

Site description

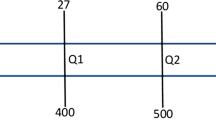

The field experiment was carried out to evaluate the effects of biochar and compost application on corn growth, productivity, and soil GHG fluxes under waterlogged conditions. Experimental plots were established at the Sunchon National University, South Korea (35° 00 × 06″ N, 127° 30 × 24″ E). The site had an average temperature of 16.7 °C over the past 5 years (2018–2022) during the corn growing season (March to July). In 2023, the average temperature was 17.1 °C, about 0.4 °C higher. Average precipitation over the past 5 years was 744 mm. In 2023, the site recorded 1.8-fold escalation against a 5-year preceding average during the corn season. Indeed, climatic abnormalities and extreme events have increased in South Korea, and the patterns and impacts vary with locations. Therefore, “one size fits all” approaches to counteract climatic effects are ineffective. Localized experiments using locally available resources, such as in this study, are necessary to identify strategies in better adapting to climatic perturbations. Average temperature and precipitation during the corn cultivation period in the experimental plots are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Baseline soil samples were collected from surface soil (15 cm) using a hand auger. The soil pH and EC were measured using a soil–water ratio of 1:5 after shaking the mixture for 30 min. Soil organic matter (OM) and total nitrogen (TN) contents were measured using the Tyurin method and Kjeldahl method, respectively. Available phosphorus (P2O5) was calculated by the Lancaster method. Soil exchangeable cations were extracted using 1 N-NH4OAc. Soil bulk density soil was determined using the core method [27]. The compost and biochars were first digested with H2SO4 + HClO4 and subsequently TN and TP analyses were carried out using the Kjeldahl method and UV spectrophotometry, respectively. The K, Ca, Mg, As, Cd, Hg, and Pb contents in compost and biochar were analyzed using an inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectrometer (ICP-AEC, Optima 3300EV, Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA). All chemical analyses were carried out using NIAST guidelines [28].

The soil texture was classified as clay loam with bulk density averaging 1.28 Mg m−3. Soil pH and EC were 5.31 and 0.29 dS m−1, respectively (Table 1). Soils in the experimental plots comprised of 25.8 g kg−1 organic matter (OM), 1.52 g kg−1 total nitrogen (TN), 67.6 mg kg−1 available phosphate (Avail. P2O5), 0.59 cmolc kg−1 K, 2.67 cmolc kg−1 Ca, 0.88 cmolc kg−1 Mg, and 9.22 cmolc kg−1 cation exchange capacity (CEC).

Experimental design

The field experiment was laid out in a complete block design with four treatments: compost (CP), rice husk biochar (RB), wood biochar (WB), and control (Cn). Individual treatment plots were 2.5 m2 in area and replicated three times. The compost used was commercially available livestock compost with 41.8% TC, 1.82% TN, 2.06% P2O5, and 1.80%. K2O. Both rice husk and wood biochars were commercially available and slightly alkaline (pH > 9) with substantial TN, TP, K, Ca, and Mg nutrients. No harmful metals (As, Cd, Hg, and Pb) were reported in biochars (Table 2).

Compost and two biochars were applied at 7.6 t ha−1 following the Soil Management and Fertilizer Recommendation guidelines provided by the Rural Development Administration (RDA), South Korea. Amendments were manually applied and later plowed to a depth of 15 cm for soil incorporation, a week prior sowing. Corn (Zea mays L.) was planted on April 3, 2023 at 30 cm spacing between the crops. Plants were harvested on July 24, 2023. Observation on growth and yield characteristics such as height, leaf and stem weight, biomass productivity, total weight, corn yield, kernel weight, and corn productivity were recorded after harvest. Also, grain index was determined using the percentage of weight ratio in corn grain yield and corncob.

Monitoring of CO2 and N2O fluxes

The CO2 and N2O fluxes (mg m−2 h−1) were monitored through a static chamber with 0.07 m2 area and 0.02 m3 volume. The chamber was placed between corn plants to a soil depth of 20 cm. Gas sampling was performed between 9 and 10 a.m. every 7 days and samples were collected at 0, 20, and 40 min after chamber closure, using a 10 mL gas tight syringe. The measurements of CO2 and N2O were simultaneously analyzed on a gas chromatograph (8892 GC System, Agilent, USA) with a flame ionization detector (FID) and an electron capture detector (ECD), respectively. Fluxes of CO2 and N2O were calculated using the following equation [29]:

where F is CO2 and N2O flux, ρ is CO2 and N2O density, V is the volume of the chamber (m3), A is the area of the chamber (m2), Δc × Δt is an average increase of gas concentration, and T is 273 + mean temperature in the chamber (°C).

The total CO2 and N2O fluxes for the entire corn cultivation were computed as described by Kang et al. [29]:

where Ri is the rate of CO2 and N2O emission in the ith sampling interval (g m−2 day−1), Di is the number of days in the ith sampling interval, and n is the number of sampling intervals.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 27. The mean values were computed as an average of three replicates. Each mean value was subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and a comparison of the treatments was performed with Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT) at 5% probability.

Results

Growth characteristics of plant and corn

Tables 3 and 4 show distinct growth and yield characteristics of corn contingent upon treatment types measured after harvest, respectively. The CP treatment emerged as the most efficacious, consistently exhibiting superior corn growth metrics. Cn registered an average plant height of 184 cm, CP 176 cm, RB 142 cm, and WB 154 cm. CP treatment demonstrated enhanced stem and leaf weights, and corn productivity relative to other treatments. Corn productivity was highest at CP treatment (25.2 t 10 a−1), followed by Cn (22.4 t 10 a−1), and the RB (11.5 t 10 a−1) and WB treatments (13.6 t 10 a−1), respectively. CP treatment manifested a pronounced enhancement in corn biomass, exceeding biomass of Cn treatment by 12.6, RB treatment by 120, and WB treatment by 86%, respectively.

The total weight of corn increased in the order: CP (237 g) > Cn (191 g) > WB (107 g) > RB (79 g). Similarly, corn yield increased in the order: CP (157 g) > Cn (119 g) > WB (71 g) > RB (53 g). Notably, there was a negligible disparity between the RB and WB treatments in straw yield, grain yield, grain index and corn productivity but both were distinctively lower than CP treatment. CP treatment registered a peak grain yield at 120 g and corn productivity at 2.51 t 10 a−1.

Changes in CO2 emission rates

Figure 2 shows the patterns of CO2 emission rates contingent upon different treatments. Notably, the CP treatment showed elevated CO2 emission rates compared to its counterparts. On the inception day of corn planting, the CO2 emission rate under the Cn treatment was measured at 89.0 mg m−2 h−1. This value escalated to its zenith during the cultivation phase, reaching 657 mg m−2 h−1 at 70 days post-planting. Subsequently, the emission rate persisted above the 400 mg m−2 h−1 threshold until the 98th day post-planting, after which a gradual decline was observed. In contrast, the CP treatment exhibited a distinctive trend: a sustained increase in CO2 emission rates post-planting, peaking at an impressive 1,096 mg m−2 h−1 on the 112th day. The RB and WB treatments showed a more transient spike, with emissions accelerating rapidly to hover between 583 and 670 mg m−2 h−1 at 56 days after planting. Post this surge, these treatments mirrored the Cn trajectory: emissions maintained around 200 mg m−2 h−1 until the 98th day, followed by a steady diminution. In terms of average CO2 emission rates over the entire measurement duration, emissions increased in the order: CP > Cn ≧ WB ≧ RB.

Changes in N2O emission rates

Figure 3 shows N2O emission rates over the duration of corn cultivation. Similar to the trends observed in CO2 emissions, CP treatment showcased a pronounced elevation in N2O emissions. The N2O emission rates during corn cultivation for the Cn treatment oscillated between 1.49 and 132 µg m−2 h−1, with an average standing at 36.6 µg m−2 h−1. For the CP treatment, the rates spanned from 4.39 to 429 µg m−2 h−1, averaging at 71.8 µg m−2 h−1. The RB treatment manifested rates between 0.99 and 152 µg m−2 h−1, with a mean value of 30.3 µg m−2 h−1. Lastly, the WB treatment exhibited a range of 2.83 to 76.1 µg m−2 h−1, culminating in an average of 22.0 µg m−2 h−1. Indeed, the total N2O flux was highest for the CP treatment (217 mg m−2) and lowest for the WB (66.5 mg m−2) treatment.

Discussion

The integration of compost and biochar into agricultural systems has long been heralded for its transformative influence on soil physicochemical and hydrological properties [21]. Its commendable role in ameliorating soil fertility, sequestering carbon, enhancing nutrient cycling, and reducing nutrient leaching and bioavailability of contaminants, has been empirically established, leading to enhanced crop yields and GHG savings [16, 30]. In this study, we observed higher biomass and yield with compost amendment but significant decrements in corn plant biomass and productivity for biochar treatments as juxtaposed against the Cn benchmark. This highlight potential benefits of compost against biochar under our conditions, offering valuable insights for yield optimization and agricultural stratification. Indeed, compost may increase crop yield by rapidly influencing soil properties and increasing plant nutrient uptake whereas biochars generally induce ameliorative effect after many years [13].

While several studies report agronomic benefits of biochar [31, 32], these benefits could vary with meteorological conditions, soil types, and biochar rate and properties [21]. In 2023, we measured 1328 mm rainfall at our site from March to July. This figure represented a substantial 1.8-fold increase against a 5-year preceding average. Such an anomalous precipitation trajectory invariably induced recurrent waterlogging, rendering different response of soil amendments, which remains uninvestigated in extant literature.

Indeed, waterlogged conditions can profoundly impede plant growth and development. Under such conditions, the soil’s oxygen scarcity impedes seed germination [33] and hinders root growth. This, in turn, leads to suboptimal nutrient absorption, invariably affecting yield outcomes [34, 35]. Kaur et al. [36] reported average corn grain yield loss of 0.42 Mg ha−1 and 0.72 Mg ha−1 in 2013 and 2014, respectively under waterlogging conditions in Northeast Missouri, USA. Soil amendments can significantly alter soil properties under waterlogged conditions to affect soil quality and crop yield. While biochar’s pronounced surface area and porosity can amplify the soil’s moisture retention [37, 38], these attributes, though beneficial under drought scenarios [39, 40], may exacerbate conditions in excessive rainfall regions, as evidenced in our experimental milieu, riffed with waterlogging. Future studies should investigate how biochar or compost properties modify soils properties and vice versa under waterlogging conditions. Importantly, we observed lower N2O flux with biochars compared to compost or control plots highlighting biochar’s pivotal role in advancing the global carbon neutrality agenda and mitigating climate change in agricultural section.

In summarize, soil amendments have ignited burgeoning interest for their potential role in rejuvenating soil fertility, enhancing soil health, increasing crop productivity, and championing climate change mitigation. This short-term study investigating the effect of compost and biochar amendments indicates that compost has potential to increase upland corn yield in waterlogged conditions. RB and WB treatments produced lower N2O flux than CP and Cn treatments. Both RB and WB treatments were indifferent across growth characteristics, yield attributes, and soil GHG fluxes. Overall, rice husk and wood biochars show potential to reduce N2O flux but multi-year and multi-site studies will be needed to fully ascertain yield benefits and GHG mitigation under waterlogging conditions. Future studies should also evaluate the effect of different rates of organic amendments and mixture of compost and biochar and assess differences in CO2 and N2O fluxes between waterlogging and dry-down conditions.

Availability of data and materials

All data is available in the main text.

Change history

13 February 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13765-024-00868-9

References

Friedlingstein P, Jones MW, O’Sullivan M, Andrew RM, Bakker DC, Hauck J, Le Quéré C, Peters GP, Peters W, Pongratz J, Sitch S (2022) Global carbon budget 2021. Earth Syst Sci Data 14(4):1917–2005

Malhi GS, Kaur M, Kaushik P (2021) Impact of climate change on agriculture and its mitigation strategies: a review. Sustainability 13:1318

Zdeněk Ž, Petr H, Karel P, Daniela S, Jan B, Miroslav T (2017) Impacts of water availability and drought on maize yield—a comparison of 16 indicators. Agric Water Manag 188:126–135

Lu HD, Xue JQ, Guo DW (2017) Efficacy of planting date adjustment as a cultivation strategy to cope with drought stress and increase rainfed maize yield and water-use efficiency. Agric Water Manag 179:227–235

Li W, Hao Z, Pang J, Zhang M, Wang N, Li X, Li W, Wang L, Xu (2019) Effect of water-deficit on tassel development in maize. Gene 681:86–92

Zhang W, Wei J, Guo L, Fang H, Liu X, Liang K, Niu W, Liu F, Siddique KHM (2023) Effects of two biochar types on mitigating drought and salt stress in tomato seedlings. Agronomy 13:1039

Zhang Y, Ding J, Wang H, Zhao C (2020) Biochar addition alleviate the negative effects of drought and salinity stress on soybean productivity and water use efficiency. BMC Plant Biol 20:288

Yildirim E, Ekinci, Turan M (2021) Impact of biochar in mitigating the negative effect of drought stress on cabbage seedlings. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr 21:2297–2309

Devi CK, Das P, Nath M, Mishra BK (2023) Attitude of farm women towards the effects of climate change in agriculture and allied activities: a study in Imphal, East districts of Manipur, India. Int J Environ Clim Change 13:3843–3849

Tian LX, Zhang YC, Chen PL, Zhang FF, Li J, Yan F, Dong Y, Feng BL (2021) How does the waterlogging regime affect crop yield? A global meta-analysis. Front Plant Sci 12:634898

Chandio AA, Jiang Y, Rehman A, Rauf A (2019) Short and long-run impacts of climate change on agriculture: an empirical evidence from China. Int J Clim Changes Strateg Manag 12:201–221

Paudel B, Acharya BS, Ghimire R, Dahal KR, Bista P (2014) Adapting agriculture to climate change and variability in Chitwan: long-term trends and farmers’ perceptions. Agric Res 3:165–174

Blanco-Canqui H, Laird DA, Heaton EA, Rathke S, Acharya BS (2020) Soil carbon increased by twice the amount of biochar carbon applied after 6 years: field evidence of negative priming. GCB Bioenergy 12(4):240–251

Cen R, Feng W, Yang F, Wu W, Liao H, Qu Z (2021) Effect mechanism of biochar application on soil structure and organic matter in semi-arid areas. J Environ Manag 286:112198

Park JH, Yun JJ, Park JH, Acharya BS, Han KJ, Cho JS, Kang SW (2023) Three years of biochar and straw application could reduce greenhouse gas and improve rice productivity. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. https://doi.org/10.1080/00380768.2023.2181623

Park JH, Yun JJ, Kim SH, Park JH, Acharya BS, Cho JS, Kang SW (2023) Biochar improves soil properties and corn productivity under drought conditions in South Korea. Biochar 5:66

Yun JJ, Park JH, Acharya BS, Park JH, Cho JS, Kang SW (2022) Production of pelleted biochar and its application as an amendment in paddy condition for reducing methane fluxes. Agriculture 12(4):470

Manik SMN, Pengilley G, Dean G, Field B, Shabala S, Zhou M (2019) Soil and crop management practices to minimize the impact of waterlogging on crop productivity. Front Plant Sci 10:140

Huang C, Gao Y, Qin A, Liu Z, Zhao B, Ning D, Ma S, Duan A, Liu Z (2022) Effects of waterlogging at different stages and durations on maize growth and grain yields. Agric Water Manag 261:107334

Agegnehu G, Bass AM, Nelson PN, Bird MI (2016) Benefits of biochar, compost and biochar–compost for soil quality, maize yield and greenhouse gas emissions in a tropical agricultural soil. Sci Total Environ 543:295–306

Blanco-Canqui H (2017) Biochar and soil physical properties. Soil Sci Soc Am J 81(4):687–711

Bis Z, Kobyłecki R, Ścisłowska M, Zarzycki R (2018) Biochar–potential tool to combat climate change and drought. Ecohydrol Hydrobiol 18(4):441–453

Mansoor S, Kour N, Manhas S, Zahid S, Wani OA, Sharma V, Wijaya L, Alyemeni MN, Alsahli AA, El-Serehy HA, Paray BA (2021) Biochar as a tool for effective management of drought and heavy metal toxicity. Chemosphere 271:129458

Dong D, Feng Q, Mcgrouther K, Yang M, Wang H, Wu W (2015) Effects of biochar amendment on rice growth and nitrogen retention in a waterlogged paddy field. J Soils Sediments 15:153–162

Si L, Xie Y, Ma Q, Wu L (2018) The short-term effects of rice straw biochar, nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizer on rice yield and soil properties in a cold waterlogged paddy field. Sustainability 10(2):537

Liu Y, Yang M, Wu Y, Wang H, Chen Y, Wu W (2011) Reducing CH4 and CO2 emissions from waterlogged paddy soil with biochar. J Soils Sediments 11:930–939

Grossman RB, Reinsch TG (2002) Bulk density and linear extensibility. In: Dane JH, Topp GC (eds) Methods of soil analysis: Part 4, SSSA Book Series 5. Madison, SSSA, pp 201–225

NIAST (2000) Methods of soil and plant analysis. National Institute of Agricultural Science and Technology, RDA, Suwon

Kang SW, Yun JJ, Park JH, Cho JS (2021) Exploring suitable biochar application rates with compost to improve upland field environment. Agronomy 11:1136

Ippolito JA, Laird DA, Busscher WJ (2012) Environmental benefits of biochar. J Environ Qual 41(4):967–972

Yeboah E, Asamoah G, Kofi B, Abunyewa AA (2016) Effect of biochar type and rate of application on maize yield indices and water use efficiency on an ultisol in Ghana. Energy Proc 93:14–18

Sarfraz R, Shakoor A, Abdullah M, Arooj A, Hussain A, Xing S (2017) Impact of integrated application of biochar and nitrogen fertilizers on maize growth and nitrogen recovery in alkaline calcareous soil. Soil Sci Plant Nutr 63:488–498

Zaman MS, Malik AI, Kaur P, Erskine W (2018) Waterlogging tolerance of pea at germination. J Agron Crop Sci 204:155–164

Ylivainio K, Jauhiainen L, Uusitalo R, Turtola E (2018) Waterlogging severely retards P use efficiency of spring barley (Hordeum vulgare). J Agron Crop Sci 204:74–85

Wollmer AC, Pitann B, Mühling KH (2018) Waterlogging events during stem elongation or flowering affect yield of oilseed Rape (Brassica napus L.) but not seed quality. J Agron Crop Sci 204:165–174

Kaur G, Zurweller BA, Nelson KA, Motavalli PP, Dudenhoeffer CJ (2017) Soil waterlogging and nitrogen fertilizer management effects on corn and soybean yields. Agron J 109(1):97–106

Wang D, Li C, Parikh SJ, Scow KM (2019) Impact of biochar on water retention of two agricultural soils—a multi-scale analysis. Geoderma 340:185–191

Qian Z, Tang L, Zhuang S, Zou Y, Fu D, Chen X (2020) Effects of biochar amendments on soil water retention characteristics of red soil at South China. Biochar 2:479–488

Ndede EO, Kurebito S, Idowu O, Tokunari T, Jindo K (2022) The potential of biochar to enhance the water retention properties of sandy agricultural soils. Agriculture, 12:311NIAST (2000) Methods of soil and plant analysis. RDA, Suwon, Korea: National Institute of Agricultural Science and Technology

Tanure MM, da Costa LM, Huiz HA, Fernandes RBA, Cecon PR, Pereira Junior JD, da Luz JMR (2019) Soil water retention, physiological characteristics, and growth of maize plants in response to biochar application to soil. Soil Tillage Res 192:164–173

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2022R1F1A1064576). Also, this research was supported by “Regional Innovation Strategy (RIS)” through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) (2021RIS-002). The authors also acknowledge the support of “Cooperative Research Program for Agriculture Science and Technology Development (Project No. PJ015568)” Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea. This work was supported by Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture, Forestry (IPET) through Technology Commercialization Support Program, funded by Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (MAFRA) (821007-3).

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H-NC, and J-SC designed and conducted the experiment. H-NC, M-JS, I-HL, H-ER, and J-HP conducted samples analysis, CO2 and N2O measurement and interpretation. B-SA, Y-HC, S-WK inspired the overall work, wrote the final draft, and revised the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised: Modifications have been made in Figure 1, Table 1, Materials and Methods, and Results section. Full information regarding the corrections made cane be found in the correction for this article.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cho, HN., Shin, M., Lee, I. et al. Impact of biochar and compost amendment on corn yield and greenhouse gas emissions under waterlogged conditions. Appl Biol Chem 66, 87 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13765-023-00845-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13765-023-00845-8