Abstract

Double-stranded RNA (dsRNA)-induced RNA interference is a promising agricultural technology for crop protection against various pathogens. Recent advances in this field have enhanced the overall efficiency with which this approach inhibits pathogenic viruses. Our previous study verified that treatment of Nicotiana benthamiana plants with dsRNAs targeting helper component-proteinase (HC-Pro) and nuclear inclusion b (NIb) genes protected the plant from pepper mottle virus (PepMoV) infection. The aim of this study was to improve the inhibitory efficacy of dsRNAs by optimizing the target sequences and their length and by targeting multiple genes via co-treatment of dsRNAs. Each of the two targeting dsRNAs were divided into three shorter compartments and we found that HC-Pro:mid-1st and NIb:mid-3rd showed significantly superior antiviral potency than the other fragments, including the parent dsRNA. In addition, we confirmed that the co-treatment of two dsRNAs targeting HC-Pro and NIb produced a greater inhibition of PepMoV replication than that obtained from individual dsRNA treatment. Complementing our previous study, this study will provide future directions for designing dsRNAs and enhancing their efficiency in dsRNA-mediated RNA interference technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

RNA interference (RNAi) is necessary to modulate the proper growth and development of plants while mediating stress responses, including biotic and abiotic/environmental stresses. RNAi requires a 20 ~ 22-nucleotide-long small interfering RNA (siRNA) that gets incorporated into an Argonaute protein and assembled into an RNA-induced silencing complex, which inhibits the expression of specific transcripts that are complementary in sequence to the siRNA [1, 2]. These siRNAs usually originate from double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) via the action of Dicer-like (DCL) proteins, such as DCL2/3/4. Based on their source, siRNAs exhibit different roles and targets. When dsRNA comes from an endogenous plant pathway, the processed siRNA targets specific transcripts in cis or trans. On the other hand, when dsRNA originates from exogenous sources like a viral genome, the processed siRNA targets viral genes and can inhibit their replication: a common antiviral defense response in plants.

Exogenous treatment of dsRNA can also induce RNAi in plants [3,4,5], opening up new applications of dsRNAs in protecting crops from plant pathogens and pests [6,7,8,9,10]. Since dsRNA-based RNAi technology does not require the host genome to be modified, it is free from issues surrounding genetically modified organisms. Moreover, it provides an excellent alternative to protect crops that are less pliable to clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/Cas9-based genome editing. This technology has previously been applied to protect plants from pathogenic viruses [4, 11,12,13,14], fungal pathogens [15,16,17], and insects [3, 18,19,20,21,22]. However, though there have been advances in large-scale dsRNA production processes during decades [23, 24], the overall cost for field application of dsRNA with agronomic purpose is still expensive compared to other pest control strategy, which is an obstacle for its practical utilization. To overcome the economic challenge, numerous studies tested and optimized the length and sequences of dsRNAs [25], or developed efficient delivery/treatment strategy to improve cost-effectiveness of dsRNA-based techniques [12, 26].

Pepper mottle virus (PepMoV) is a devastating plant pathogen that infects most Capsicum species and causes deleterious economic losses. PepMoV has a single-stranded positive-sense RNA genome, nearly 10 kb in length [27]. It encodes a single large polyprotein, which is further processed into smaller mature proteins inside the host [28, 29]. In our previous study, we verified that dsRNAs targeting two genes of PepMoV, helper component-proteinase (HC-Pro) and nuclear inclusion b (NIb), efficiently suppressed PepMoV proliferation in tobacco plants [4]. Moreover, we traced the effective location and sequence of the RNA that is key to the RNAi mechanism. We also established that the naked dsRNAs lasted 8–10 days inside the host. These findings posed the question whether a more optimized sequence could be found to improve the overall silencing efficiency.

Herein, we considered further optimization of PepMoV-targeting dsRNAs and their treatment strategies to improve efficiencies and cost-effectiveness. To do this, we examined the PepMoV inhibitory effect of dsRNAs which are shortened by dividing previously defined dsRNA sequences into three compartments. In addition, we examined the inhibitory efficacy of two different dsRNA treatment strategies, and observed the improvement of PepMoV inhibitory effects by targeting multiple viral genes through the co-treatment of HC-Pro and NIb dsRNAs.

Materials and methods

Preparation of plant and virus inoculum

Tobacco plants (Nicotiana benthamiana) were used in this study. Three-week-old N. benthamiana plants were inoculated with dsRNA and PepMoV. They were grown in a growth chamber under a 16 h/8 h light/dark cycle at 25 ℃. An infectious full-length cDNA clone of PepMoV isolate 134 (pPepMoV:GFP-134) was used as described in a previous study [4]. pPepMoV:GFP-134 was transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 for use in agro-infiltration.

Design and synthesis of PepMoV-targeting dsRNA

Sequences of HC-Pro:mid (530 bp) and NIb:mid (555 bp) were used as described in our previous study [4]. Short compartments of HC-Pro:mid and NIb:mid were designed by dividing them into three fragments, each about 210–223 bp long, respectively (Additional file 1: Table S1). dsRNA sequences, 500 bp long, from the Renilla luciferase gene, were used as a negative control.

To synthesize dsRNAs, primers containing the T7 promoter sequence (5′-TAA TAC GAC TCA CAT ATA AGA GAG -3′) at their 5′ end and specific sequences complementary to each template DNA were used (Additional file 2: Table S2). dsDNA templates for in vitro transcription were amplified using primers and dsRNA-corresponding sequences. dsRNAs were synthesized by in vitro transcription with T7 promoter-containing DNA template and the MEGAscript RNAi kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instruction. After purification, the quality of synthesized dsRNAs was confirmed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Inoculation of virus and dsRNA into the plants

The virus was inoculated as previously described [4]. Briefly, Agrobacterium strains containing the pPepMoV:GFP-134 clone were added to yeast extract beef broth containing kanamycin and rifampicin. After 24 h, acetosyringone was added and incubated for 16 h. Cell cultures were collected, suspended, and diluted in MMA buffer.

To inoculate the synthesized dsRNAs into N. benthamiana, 30 µg of each dsRNA was prepared and diluted in RNase-free water to obtain a final concentration of 7.5 µg/mL. For the co-treatment experiment, 15 µg each of HC-Pro:mid-1st and NIb:mid-3rd dsRNAs were mixed in RNase-free water to obtain a final total dsRNA concentration of 7.5 µg/mL.

Each dsRNA was inoculated using syringes into the fully expanded leaves of 3-week-old plants through their abaxial side. To provide time for dsRNA to be processed inside the plants, infectious pPepMoV:GFP-134 clone-containing Agrobacterium cells were inoculated 48 h after dsRNA treatment.

Measuring GFP expression

GFP signals from infiltrated leaves were captured under a blue light lamp (Dark Reader Hand Lamp HL32T, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) with a digital camera (Nikon 7200, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a longpass filter (495 nm) combined with a green filter (G(X1), Hoya, Japan).

Total RNA isolation, reverse transcription, and quantitative PCR

Sampling was performed after screening the GFP expression level. Total RNA was extracted using RiboEX (GeneAll, South Korea), according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and its quality and quantity were confirmed on NanoDrop (Thermo Scientific, United States). For eliminating residual DNA, the extracted RNA was treated with Recombinant DNase I (Takara Bio, Japan). cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using PrimeScript reverse transcriptase (Takara Bio, Japan). Quantitative real-time PCR with a SYBR Green detector was performed using cDNA and gene-specific primers described in the previous study [4]. The GFP expression level was measured by the 2−ΔΔCT method using L23 as a reference gene (Additional file 3: Table S3) [30, 31]. The significance of GFP transcript level differences measured by qRT-PCR was tested by the Student’s t-test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001).

Results

Short dsRNA compartments of HC-Pro and NIb are sufficient to suppress PepMoV infection

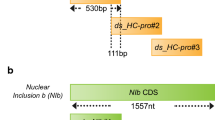

In our previous study, we divided the sequence of two target genes, HC-Pro and NIb, into three compartments having similar lengths and examined the PepMoV inhibitory effect exerted by dsRNAs synthesized for each compartment. We found that the central dsRNA compartment from both genes suppressed PepMoV most significantly [4]. This finding suggests that there are specific regions which are optimal for dsRNA-mediated inhibition. It is known that the overall inhibitory effect of exogenous dsRNA can be determined by sequence and length which affect uptake and process required for RNAi mechanism [7], In addition, the inhibitory effect can vary depending on pathogen types and genes targeted by dsRNAs [32]. The known range of dsRNA length for pronounced effect on virus in plants is about 200 bp to 2 kb [6], suggesting that the length of our previous dsRNA could be shortened while their inhibitory efficacies are maintained or improved by precisely targeting a core region of virus genes. To confirm this, we further narrowed down the effective dsRNA region. The central dsRNA compartment of each target gene was divided into three shorter compartments, ~ 220 bp in length, while maintaining the overall treatment dosage (Fig. 1). Their antiviral effects were assayed using GFP-tagged PepMoV.

Design of short dsRNA compartments targeting HC-Pro and NIb. a Double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) design targeting the central region of HC-Pro. Regions that were 530 bp in length were divided into three compartments, 220-bp-long with an overlap of 80 bp. b dsRNA design targeting the central region of NIb. Regions that were 555 bp in length were divided into three compartments, 223-bp-long with an overlap of 57 bp

In the case of HC-Pro-targeting dsRNAs, the strongest viral suppression was observed in local leaves of 8-days-post-inoculation (dpi) plants inoculated with HC-Pro:mid-1st dsRNA, the compartment located near the 5′ end of HC-Pro:mid. Its effect was stronger than that elicited by the other two compartments as well as HC-Pro:mid itself (Fig. 2). In addition, during the transition from 5-dpi to 8-dpi, the increase in GFP signal in HC-Pro:mid-1st-treated plants was only limited to local leaves. Like plants treated with HC-Pro:mid, those treated with HC-Pro:mid-1st also exhibited only a mild increase in GFP signal, indicating that PepMoV proliferation was successfully delayed by dsRNA treatment. On the other hand, HC-Pro:mid-2nd- and HC-Pro:mid-3rd-treated plants showed severe increases in GFP signals in both local and systemic leaves, highlighting the inefficiency of these dsRNAs in inhibiting virus proliferation (Fig. 3). Consistently, plant growth phenotypes observed on 12 dpi revealed a better antiviral efficacy offered by HC-Pro:mid-1st compared with HC-Pro:mid-2nd and HC-Pro:mid-3rd (Fig. 2). Quantitative PCR results from local leaves of 8-dpi plants also reflected the superior antiviral potency of HC-Pro:mid-1st dsRNA compared with the entire HC-Pro:mid dsRNA at a molecular level (Fig. 3). HC-Pro:mid-2nd and HC-Pro:mid-3rd dsRNAs exhibited similar levels of PepMoV suppression to the entire HC-Pro:mid dsRNA; however, plants inoculated with HC-Pro:mid-2nd and HC-Pro:mid-3rd dsRNAs were severely infected at 8 dpi compared with those inoculated with HC-Pro:mid whole dsRNA. These results suggest that HC-Pro:mid-1st contains sequences that are effective in suppressing PepMoV proliferation.

PepMoV inhibitory efficacy of HC-Pro- and NIb-targeting short dsRNA compartments. Pepper mottle virus (PepMoV) infection status and growth phenotypes of HC-Pro- and NIb-targeting dsRNA-treated plants at 5-/8-/12-days post-inoculation (dpi). Green fluorescent protein (GFP) signals (bright-green colors in images of 5-dpi and 8-dpi plants) represent the infectious PepMoV clones inside the plants

GFP transcript levels measured by quantitative PCR. Levels of GFP transcript tagged to the PepMoV genome were measured by quantitative PCR in the local leaves of dsRNA-treated plants at 8 dpi. R.luc indicates the plants treated with dsRNA containing partial sequences (500-bp-long) of Renilla luciferase. The relative expression level of each sample was measured and compared with non-dsRNA-treated plants. The data represents the average of three independent experiments and error bars represent SEM. Significance is determined by Student’s t-test, *: P < 0.05, **: P < 0.01

In the case of NIb-targeting dsRNAs, NIb:mid-2nd and NIb:mid-3rd successfully suppressed systemic leaf infection in 8-dpi plants to an extent similar to that in NIb:mid-treated plants (Fig. 2). Quantitative PCR demonstrated that NIb:mid-3rd produced the most substantial level of suppression, whereas NIb:mid-2nd induced inconsistent suppression between replicates (Fig. 3). These results suggest that NIb:mid-3rd is the most effective region for suppressing PepMoV among the three compartments of NIb:mid.

Overall, these findings show that specific, short dsRNA compartments, 210 ~ 230 bp long, are sufficient to suppress PepMoV proliferation in tobacco plants to a level similar to or higher than the parent dsRNAs.

Additional dsRNA treatment after PepMoV infection delays PepMoV proliferation

Since we previously observed inhibitory effects when dsRNA was treated prior to PepMoV infection [4], we examined whether supplementing dsRNA with PepMoV infection could prolong viral suppression. We inoculated plants additionally with dsRNAs at 3 dpi and 5 dpi, and recorded their GFP signals and growth phenotypes. We observed attenuated GFP signals in 8-dpi plants additionally treated with HC-Pro:mid-1st at 3 dpi. On the other hand, no notable differences could be observed between plants treated with HC-Pro:mid-1st once and those additionally treated with HC-Pro:mid-1st at 5 dpi (Fig. 4). In case of NIb-targeting dsRNA, additional treatment did not show any significant differences on systemic leaves compared with the single-treatment in 8-dpi plants (Fig. 4). These results suggest that enhancement of PepMoV inhibitory effect by supplementary dsRNA treatment may depend on targeted genes, and interval between the first and additional dsRNA treatment.

Additional treatment of dsRNAs did not improve PepMoV suppression in N. benthamiana. PepMoV infection status and growth phenotypes of HC-Pro-targeting and NIb-targeting dsRNA-treated plants at 5/8/12 dpi. First dsRNA dose was inoculated 2 days before PepMoV infiltration. Additional dsRNA treatments were conducted at 3 dpi or 5 dpi. For each treatment, the dose of infiltrated dsRNA was fixed at 30 µg per plant into the local leaves. GFP signals (bright-green colors in images of 5-dpi and 8-dpi plants) represent infectious PepMoV clones inside the plants

Co-treatment of dsRNA molecules can effectively inhibit PepMoV

Replication, movement, transmission, and encapsidation are crucial steps in viral infection cycle [33]. Inhibiting even one of these steps will abrogate viral infection. HC-Pro and NIb are crucial genes for these steps. HC-Pro is essential for transmission of virus while NIb is vital for replication [34, 35]. Therefore, we hypothesized that co-silencing both of the genes would enhance viral inhibition. Also, considering that plant microorganisms express multiple genes during infection, simultaneous treatment with dsRNAs targeting different viral genes may produce a better inhibitory effect. The promising effect elicited by the supplementary treatment of dsRNAs further justifies our co-treatment strategy. To examine this idea, we prepared a 1:1 mixture of HC-Pro:mid-1st and NIb:mid-3rd and compared their inhibitory effects with those produced by each dsRNA molecule alone.

Systemic leaves of all PepMoV-infected plants, including those treated with the individual dsRNAs, showed significant GFP signals at 10 dpi, suggesting that dsRNA’s inhibitory effect was not retained until this later timepoint. However, we observed a significant attenuation in GFP signal in 10-dpi plants treated with the dsRNA mixture compared with non-treated plants or those treated with individual dsRNAs (Fig. 5a). Quantitative PCR on the GFP transcript also consistently supported this finding (Fig. 5b). Since the total dosage of dsRNA was maintained constant at 30 µg across all the treatments, these results suggest that, even though the individual dose of each dsRNA decreased, their overall inhibitory effect was more pronounced and prolonged when multiple PepMoV genes were targeted.

Co-treatment of two dsRNAs successfully delayed PepMoV infection in N. benthamiana. a PepMoV infection status of dsRNA mixture-treated plants at 5/8/10 dpi. dsRNA mixture for infiltration was prepared by mixing 15 µg of each short dsRNA compartment (selected from the results shown in Fig. 2. and Fig. 3). GFP signals (bright-green colors in images of 5-dpi and 8-dpi plants) represent infectious PepMoV clones inside the plants. b GFP transcript levels measured by quantitative PCR in the local leaves of 8-dpi co-treated plants. R.luc indicates the plants treated with dsRNA containing partial sequences (500-bp-long) of Renilla luciferase. Data are presented as mean (± SEM; n = 3). Significance is determined by Student’s t-test

Discussion

When we examined the inhibitory efficacy of each short dsRNA compartment, we maintained the treatment dosage at 30 μg. As dsRNA became shorter, its molar concentration would increase. Therefore, expecting enhanced inhibitory effects from all three short dsRNA compartments seemed reasonable. However, only one dsRNA compartment each for both of the genes suppressed PepMoV infection to a higher extent than the corresponding parent strands, suggesting two possibilities: (i) those particular dsRNA compartments include sequences preferred during the RNAi mechanism, such as efficient siRNA biogenesis, preferential Argonaute loading, and less off-target effects, or (ii) those sequences could be recognized by plants as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). Viral dsRNA is capable of inducing PAMP-triggered immunity responses [36,37,38]. If a specific dsRNA compartment acts as a PAMP but others do not, removing the non-PAMP sequences while maintaining the total dsRNA dosage would lead to an increased concentration of PAMP-dsRNA, triggering enhanced immune responses compared with those by whole dsRNA fragments, contributing to the antiviral defense of plants. In addition, if the length of exogenous dsRNA is designed to be shorter, its synthesis would be more efficient than that of relatively longer dsRNAs.

Although we injected dsRNAs 2 days before PepMoV infection, they would be continuously consumed through the DCL-mediated siRNA biogenesis pathway. On the other hand, the expression of HC-Pro (encoding RNA silencing suppressor protein) would increase due to the replication of PepMoV genome, and this may lead to suppression of dsRNA-mediated RNAi in plants. This might be the reason why additional dsRNA treatment at 5 dpi did not work well compared with that at 3 dpi, because at that time, the copy-number of PepMoV genomes and the amount of HC-Pro proteins would be high enough to suppress RNAi machinery. Moreover, additional dsRNA was injected into the same place as the first dose of dsRNA and the virus, and PepMoV was already actively replicating by that time. Our previous study supports this by showing that the inhibitory effect of dsRNAs was significantly decreased when they were treated with PepMoV at the same time or after PepMoV infections [4].

Most trials for developing effective antiviral or antipest dsRNAs focus on examining the efficacy of single target genes. However, our study proves that targeting multiple genes through the co-treatment of two dsRNAs is a more promising strategy with an improved overall inhibitory efficacy. A similar trial was conducted against vesicular stomatitis virus: two dsRNA sequences, each targeting a different gene, were combined into a single dsRNA molecule and its potency was examined in mammalian cells [39]. The amount of the target proteins and the viral titer, both, were successfully suppressed, demonstrating the antiviral validity of this approach. The efficacy of these multiple gene-targeting strategies might depend on the numbers and combinations of these genes as well as their biological impacts on the proliferation of viruses, which requires in-depth, systematic knowledge of each target virus. For example, more enhanced inhibition of PepMoV could be expected if, together with HC-Pro and NIb, other genes such as CI or P3N-PIPO, responsible for virus replication and intercellular movement, were also silenced [27]. Through further investigation of factors and the target organism’s biology, multiple gene-targeting is expected to be a mainstay in dsRNA-based plant antivirus control.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- RNAi:

-

RNA interference

- siRNA:

-

Small interfering RNA

- dsRNA:

-

Double-stranded RNA

- DCL:

-

Dicer-like

- PepMoV:

-

Pepper mottle virus

- GFP:

-

Green fluorescent protein

- PAMP:

-

Pathogen-associated molecular pattern

References

Kamthan A, Chaudhuri A, Kamthan M, Datta A (2015) Small RNAs in plants: recent development and application for crop improvement. Front Plant Sci 6:208

Shin SY, Shin C (2016) Regulatory non-coding RNAs in plants: potential gene resources for the improvement of agricultural traits. Plant Biotechnol Rep 10:35–47

Zhang J, Khan SA, Hasse C, Ruf S, Heckel DG, Bock R (2015) Pest control. Full crop protection from an insect pest by expression of long double-stranded RNAs in plastids. Science 347:991–994

Yoon J, Fang M, Lee D, Park M, Kim K-H, Shin C (2021) Double-stranded RNA confers resistance to pepper mottle virus in Nicotiana benthamiana. Appl Biol Chem 64(1):1–8

Park M, Um TY, Jang G, Choi YD, Shin C (2022) Targeted gene suppression through double-stranded RNA application using easy-to-use methods in Arabidopsis thaliana. Appl Biol Chem 65(1):1–8

Dubrovina AS, Kiselev KV (2019) Exogenous RNAs for gene regulation and plant resistance. Int J Mol Sci 20(9):2282

Das PR, Sherif SM (2020) Application of Exogenous dsRNAs-induced RNAi in agriculture: challenges and triumphs. Front Plant Sci 11:946

Christiaens O, Whyard S, Velez AM, Smagghe G (2020) Double-stranded RNA technology to control insect pests: current status and challenges. Front Plant Sci 11:451

Dalakouras A, Wassenegger M, Dadami E, Ganopoulos I, Pappas ML, Papadopoulou K (2020) Genetically modified organism-free RNA interference: exogenous application of RNA molecules in plants. Plant Physiol 182:38–50

Akbar S, Wei Y, Zhang MQ (2022) RNA interference: promising approach to combat plant viruses. Int J Mol Sci 23(10):5312

Konakalla NC, Kaldis A, Berbati M, Masarapu H, Voloudakis AE (2016) Exogenous application of double-stranded RNA molecules from TMV p126 and CP genes confers resistance against TMV in tobacco. Planta 244:961–969

Mitter N, Worrall EA, Robinson KE, Li P, Jain RG, Taochy C, Fletcher SJ, Carroll BJ, Lu GQ, Xu ZP (2017) Clay nanosheets for topical delivery of RNAi for sustained protection against plant viruses. Nat Plants 3:16207

Worrall EA, Bravo-Cazar A, Nilon AT, Fletcher SJ, Robinson KE, Carr JP, Mitter N (2019) Exogenous application of RNAi-inducing double-stranded RNA inhibits aphid-mediated transmission of a plant virus. Front Plant Sci 10:265

Rego-Machado CM, Nakasu EYT, Silva JMF, Lucinda N, Nagata T, Inoue-Nagata AK (2020) siRNA biogenesis and advances in topically applied dsRNA for controlling virus infections in tomato plants. Sci Rep 10:22277

Koch A, Biedenkopf D, Furch A, Weber L, Rossbach O, Abdellatef E, Linicus L, Johannsmeier J, Jelonek L, Goesmann A et al (2016) An RNAi-based control of Fusarium graminearum infections through spraying of long dsRNAs involves a plant passage and is controlled by the fungal silencing machinery. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005901

Wang M, Weiberg A, Lin FM, Thomma BP, Huang HD, Jin H (2016) Bidirectional cross-kingdom RNAi and fungal uptake of external RNAs confer plant protection. Nat Plants 2:16151

McLoughlin AG, Wytinck N, Walker PL, Girard IJ, Rashid KY, de Kievit T, Fernando WGD, Whyard S, Belmonte MF (2018) Identification and application of exogenous dsRNA confers plant protection against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and Botrytis cinerea. Sci Rep 8:7320

Zhang H, Li H, Guan R, Miao X (2015) Lepidopteran insect species-specific, broad-spectrum, and systemic RNA interference by spraying dsRNA on larvae. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 155(3):218–28

Nitnavare RB, Bhattacharya J, Singh S, Kour A, Hawkesford MJ, Arora N (2021) Next generation dsRNA-based insect control: success so far and challenges. Front Plant Sci 12:673576

Sharif MN, Iqbal MS, Alam R, Awan MF, Tariq M, Ali Q, Nasir IA (2022) Silencing of multiple target genes via ingestion of dsRNA and PMRi affects development and survival in Helicoverpa armigera. Sci Rep 12:10405

Jain RG, Fletcher SJ, Manzie N, Robinson KE, Li P, Lu E, Brosnan CA, Xu ZP, Mitter N (2022) Foliar application of clay-delivered RNA interference for whitefly control. Nat Plants 8:535–548

Dhandapani RK, Gurusamy D, Palli SR (2022) Protamine-Lipid-dsRNA nanoparticles improve RNAi efficiency in the fall Armyworm. Spodoptera frugiperda J Agric Food Chem 70:6634–6643

Gan D, Zhang J, Jiang H, Jiang T, Zhu S, Cheng B (2010) Bacterially expressed dsRNA protects maize against SCMV infection. Plant Cell Rep 29:1261–1268

Posiri P, Ongvarrasopone C, Panyim S (2013) A simple one-step method for producing dsRNA from E. coli to inhibit shrimp virus replication. J Virol Methods. 188:64–69

He W, Xu W, Xu L, Fu K, Guo W, Bock R, Zhang J (2020) Length-dependent accumulation of double-stranded RNAs in plastids affects RNA interference efficiency in the Colorado potato beetle. J Exp Bot 71:2670–2677

Hernández-Soto A, Chacón-Cerdas R (2021) RNAi crop protection advances. Int J Mol Sci 22(22):12148

Fang M, Yu J, Kim KH (2021) Pepper mottle virus and its host interactions: current state of knowledge. Viruses 13(10):1930

Vance VB, Moore D, Turpen TH, Bracker A, Hollowell VC (1992) The complete nucleotide sequence of pepper mottle virus genomic RNA: comparison of the encoded polyprotein with those of other sequenced Potyviruses. Virology 191:19–30

Ala-Poikela M, Rajarnaki ML, Valkonen JPT (2019) A novel interaction network used by Potyviruses in virus-host interactions at the protein level. Viruses-Basel 11(12):1158

Liu DS, Shi LD, Han CG, Yu JL, Li DW, Zhang YL (2012) Validation of reference genes for gene expression studies in virus-infected Nicotiana benthamiana using quantitative real-time PCR. Plos ONE 7(9):e46451

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(T)(-Delta Delta C) method. Methods 25:402–408

Morozov SY, Solovyev AG, Kalinina NO, Taliansky ME (2019) Double-stranded RNAs in plant protection against pathogenic organisms and viruses in agriculture. Acta Naturae 11:13–21

Makinen K, Hafren A (2014) Intracellular coordination of Potyviral RNA functions in infection. Front Plant Sci 5:110

Shen W, Shi Y, Dai Z, Wang A (2020) The RNA-dependent RNA polymerase NIb of Potyviruses plays multifunctional, contrasting roles during viral infection. Viruses 12(1):77

Valli AA, Gallo A, Rodamilans B, Lopez-Moya JJ, Garcia JA (2018) The HCPro from the potyviridae family: an enviable multitasking helper component that every virus would like to have. Mol Plant Pathol 19:744–763

Niehl A, Wyrsch I, Boller T, Heinlein M (2016) Double-stranded RNAs induce a pattern-triggered immune signaling pathway in plants. New Phytol 211:1008–1019

Samarskaya VO, Spechenkova N, Markin N, Suprunova TP, Zavriev SK, Love AJ, Kalinina NO, Taliansky M (2022) Impact of exogenous application of Potato Virus Y-specific dsRNA on RNA interference, pattern-triggered immunity and poly(ADP-ribose) metabolism. Int J Mol Sci 23(14):7915

Niehl A, Heinlein M (2019) Perception of double-stranded RNA in plant antiviral immunity. Mol Plant Pathol 20:1203–1210

Semple SL, Au SKW, Jacob RA, Mossman KL, DeWitte-Orr SJ (2022) Discovery and use of long dsRNA mediated RNA interference to stimulate antiviral protection in interferon competent Mammalian cells. Front Immunol 13:859749

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for helpful discussions with members of the Shin laboratory.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2021R1A5A1032428 and No. 2022R1A2C1011032). This was also supported by a grant from the New breeding technologies development Program (Project No. PJ01652102), Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CS, K-HK conceived the project. YK, MF, DL performed experiments. CS, K-HK, SYS, YK, and MF wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Sequence of HC-Pro and NIb genes.

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Primer sequences used in dsRNA synthesis.

Additional file 3: Table S3.

Primer sequences used in quantitative PCR.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kweon, Y., Fang, M., Shin, SY. et al. Sequence optimization and multiple gene-targeting improve the inhibitory efficacy of exogenous double-stranded RNA against pepper mottle virus in Nicotiana benthamiana. Appl Biol Chem 65, 87 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13765-022-00756-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13765-022-00756-0