Abstract

The human gastrointestinal tract harbors a magnitude of bacteria, which are collectively known as the gut microbiome. Research has demonstrated that the gut microbiome significantly impacts the health of its host and alters the host’s risk for various chronic diseases. Many factors, such as diet, could potentially be manipulated to alter the host gut microbiome and induce subsequent preventative and/or therapeutic effects. It has been established that diet partakes in the regulation and maintenance of the gut microbiome; however, specific crosstalk between the microbiome, gut, and host has not been clearly elucidated in relation to diet. In this review of the scientific literature, we outline current knowledge of the differential effects of major plant-derived dietary constituents (fiber, phytochemicals, vitamins, and minerals) on the diversity and composition of the gut microbiome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The human gut harbors more than 100 trillion bacteria, along with fungi and viruses that form the gut microbiome. This astonishingly diverse population includes significant amounts of genetic information, which is estimated to be over 150 times more than the human genome [1], thus playing a key role in host health and diseases. Recent advances in technology have made studies on the human microbiome more feasible; the majority of studies have categorized the gut microbiome per operational taxonomic units based on bacterial 16S ribosomal DNAs. Now, vast studies are generating a map of the entire metagenome to better understand functional signatures of the gut microbiome and their potential roles in one’s health status (i.e., Crohn’s disease [2]). Of the many known factors influencing the dynamics of the gut microbiome and its functional signatures, diet has been implicated as one of the most relevant factors. For instance, in a 2.5-year case study of the human infant gut microbiome, major taxonomic groups showed dramatic shifts corresponding to changes in the diet while age only resulted in a smooth temporal gradient [3]. Further, other studies showed that the gut microbiome (and their clusters) was strongly associated with long-term diet, particularly macro-nutrients in healthy young subjects [4] and elderly subjects [5], reinforcing the notion that diet is a critical determinant of the gut microbiome.

Given that (1) the gut microbiome is critical in host’s health and disease etiology, and (2) diet plays a significant role in regulating and maintaining signatures of gut microbiome, it is important and timely to comprehensively review and update evidence regarding the effects of nutrients on gut microbiome dynamics and their potential mechanisms. Therefore, in this review, we aimed to review the recent evidence regarding associations between the human gut microbiome and vegetables, specifically major plant-derived dietary constituents: fiber, vitamins, minerals, and nutritive phytonutrients.

Health promoting effects of dietary fibers and suggested mechanisms

Types of fibers and dietary sources

Dietary fibers have proven to have beneficial physiological effects on humans (e.g., body weight management [6]). Dietary fiber can be subdivided into non-fermentable/insoluble and fermentable/soluble forms, which can vary in their potential impact on health (Table 1). Physicochemical characteristics of fiber include origin, solubility and viscosity, fermentability, and chemical structure [7].

Insoluble dietary fibers (e.g., celluloses, hemicellulose, and fructans [8]) are present in foods such as whole wheat flour, brown rice, nuts, beans, and vegetables (e.g., cauliflower, broccoli, celery) [9, 10]. These fibers are characterized by their bulking effect and high fermentation by the gut microbiota, resulting in short-chain fatty acid (SCFAs) production [7]. A recent study showed that butyrate, an SCFA, causes an immunologic alteration in macrophages, and increased expression in antibacterial and host defense genes [11]. Along with the beneficial increase in SCFAs, insoluble fiber can lead to a healthy microbial composition [7]. In contrast, Desai et al., demonstrated that a fiber-deprived microbiota can increase disease susceptibility by a reduction in protective mucus; the decrease in mucus membrane, which aids in blocking pathogens entering the system, was due to an increase in mucin-degrading bacteria resulting from a deficiency in fiber [12].

Soluble fibers (e.g., pectin, guar gum, and some inulin) are present in whole grains (e.g., oats, wheat), legumes (e.g., lentils, split peas, various types of beans), seeds and nuts (e.g., flax seed), and some fruits and vegetables (e.g., carrots, apples) [13]. In contrast to insoluble fibers, soluble fibers are characterized as viscous, creating a gel-like form in the intestine which may slow absorption of nutrients (e.g., glucose and lipids [7]). In a recent study, Bang et al. found that consumption of pectin, a soluble fiber, results in the use of galacturonic acid, as an energy source for microbes, hence increasing reducing sugar levels in human stool [14]. This study shows the protective potential of pectin (a soluble fiber) against metabolic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes via controlling blood glucose levels [14].

Prebiotics are another class of insoluble fibers, and were originally defined as “non-digestible compounds that, when consumed, induce changes in composition and/or activity of the gastrointestinal bacteria, thus causing benefit(s) upon host health” [15]. Classification of prebiotics is based on three criteria; (a) resistance to gastric acidity, hydrolysis by mammalian enzymes, and gastrointestinal absorption, (b) fermentation by intestinal microbiota, and (c) selective stimulation of the growth and/or activity of intestinal bacteria associated with health and well-being [16, 17]. Positive functional characteristics of prebiotics have been reported including, but not limited to: (a) selective fermentation, (b) modulation of gut pH, (c) fecal bulking, (d) the prevention of gut colonization by pathogens, and (e) the control of putrefactive bacteria, thus reducing the host’s exposure to toxic metabolites [18]. Types (and sources) of prebiotics, include β-glucan (in mushrooms, and cereal grains) [9], fructooligosaccharide [14, 19], oligofructose [19], inulin [10, 12, 14], galactooligosaccharides (glycosylation of primary lactose) [19], guar gum (in cereal grains) [19], resistance starches and maltodextrin (e.g., starches) [10, 20], xylooligosaccharides and arabinooligosaccharides (in cereals, bars, and dairy products) [19]. Consumption of prebiotics is known to change intestinal microbiota diversity and to increase the production of SCFAs (i.e., propionate, and butyrate) [9, 19, 21, 22]. For instance, Carlson et al. found that prebiotics (e.g., β-glucan, xylooligosaccharides, and pure inulin) were effective to promote the formation of beneficial SCFAs in human subjects [19].

Production of SCFAs

SCFAs are produced by the intestinal microbiota via fermentation of carbohydrates [9, 14] and other non-absorbable nutrients [19, 21]. The most abundant SCFAs include acetate (C2), propionate (C3), and butyrate (C4), which exist in a 3:1:1 ratio [23, 24], and represent 90–95% of all SCFAs produced in the colon [14, 19, 22]. Production of these SCFAs can either be used by downstream bacterial species (cross feeding) and/or by the host as nutrient sources. Specifically, acetate and propionate can be absorbed by the lumen and enter peripheral circulation to be involved in overall metabolic homeostasis [25], while butyrate (C4) serves over 70% of the energy supply for colonocytes [26]. Among the three SCFAs, butyrate was frequently reported to be involved in other functions such as immune regulation [27], cell growth [28, 29], intestinal barrier function [30], and ion transport [31].

Supplementation of insoluble fibers may result in increased butyrate production which is highly associated with an individual’s gut microbiome composition [32]. Two main steps are involved in the butyrate production: butyrate synthesis and polysaccharide degradation [32]. Primary degraders attack specific polymer bonds to generate mono and di-oligosaccharides, allowing them to be further fermented into butyrate by secondary producers. These two steps can vary among different strains, and the metabolites synthesized during these two steps could cross-feed each other through a complex metabolic process. However, both reaction efficiencies need to be balanced or the polysaccharide degrader will consume the majority of the available carbon and energy [32]. Eubacterium rectale and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii are two main species involved in butyrate production in the human gut [33], while other species are resistant to starch degradation such as Ruminococcus and Bifidobacterium [34]. The efficiencies of butyrate production differ in people with various dietary, genetic, health and geographic backgrounds [35, 36], warranting a greater understanding of individual supplementation plans.

Effects of dietary fibers on epithelial barrier functions

The intestine is a multi-functional tubular organ containing developed vasculature, lymphatic drainage, and extensive innervation. The outside layer of the intestinal tubulin is muscular tissue, and the innermost layer is structured as a single layer of polarized epithelial cells interfacing between the external environment and inner host tissues. The single layered enterocytes are concatenated through tight junctions (TJs) to form the first layer of immune defensive translocation of food-borne pathogens or other ingested toxic compounds [37]. An intact intestinal cell wall is a prerequisite for regular gastrointestinal homeostasis but still, pathogens such as Salmonella typhimurium, Clostridium perfringens, and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli can invade the host by disturbing the TJ complex [38]. The construction of TJs is dynamic and regulated by enterocytes’ histological development and certain signaling pathways (i.e., tumor necrosis factor-α) that are initiated by pathogens. TJs also serve as the point of attack for receptors of pathogenic bacteria to invade the host and cause increased permeability, which further result in destructive intravenous electrolyte exchange, microbial dysbiosis, and diarrhea [33].

Dietary fibers and SCFAs are implicated with epithelial barrier functions. Specifically, butyrate has a bi-directional effect on epithelial barrier function. For instance, when experiencing diarrhea and antibiotic induced dysbiosis, commensal bacteria responsible for butyrate production are significantly decreased [39]. Decreased commensal bacteria causes a shortage of available butyrate as an energy source for colonocytes, thereby disrupting the enterocyte refreshment. In humans, supplementation of certain fibers can enrich butyrate producing bacteria in the gut; as the butyrate production increases, a corresponding alteration and reduction in the diarrhea condition occurs [40]. Butyrate is also known to improve the barrier function through nourishing TJs such as beta defensin, cingulin, ZO-1 and ZO-2 proteins in chicken HD11 macrophage cells, primary monocytes, bone marrow cells, and jejunal and cecal explants [41]. Similar findings were found in another study using in vitro Caco-2 human epithelial colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line, in which butyrate was able to offset barrier impairment of Campylobeacter jejuni. In addition, intracellular signaling pathways initiated by butyrate related to barrier function have been studied. For example, it is reported that butyrate enhances the TJs through activating Akt/mTOR pathways and ATP replenishment [42]. Another study indicated that dietary butyrate promotes barrier function by repressing interleukin 10 (IL-10) receptor-dependent claudin-2 [43]. IL-10 receptor contains two ligand-binding subunits: ligand-binding alpha subunit (IL-10RA) and beta subunit (IL-10B) [44]. When IL-10 binds to IL10R, it activates JAK-STAT signaling pathway, in which STAT3 activation is critical to anti-inflammatory activity [45, 46]. Butyrate was found to promote epithelial barrier function through IL-10RA repression of Claudin-2, which regulates paracellular channels for small cations and water, stimulating diarrhea via the leak-flux mechanism [43].

Anti-inflammatory effects of dietary fibers

The gut possesses one of the largest immune systems in humans, exerting both physical (i.e., barrier function) and biochemical defenses against invading foodborne pathogens and other hazards [47]. The pro-inflammatory response acts by first being triggered in the primary reaction to invaders, and then proceeding recruitment or initiation of the amplification [48]. Subsequently, cells are differentiated into multiple sub-types of immune cells to the impaired locations as a natural response to invading antigens [49]. This whole process gradually accumulates and strengthens within the first couple of days at the expense of great amounts of energy and nutrient consumption. The gastrointestinal epithelial cells, covered with an array of ligand receptors, are constantly encountering various toxic compounds or pathogens that could easily and frequently activate the immune response. Therefore, certain immunologic derangement diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and autoimmune disease could occur [50, 51]. Anti-inflammation, which serves as an inhibitory effect on excessive inflammation, is needed to maintain a balanced immune homeostasis.

Butyrate has been widely studied as an anti-inflammation regulator through modulating cytokine production, kinase activity, and immune-associated signaling pathways. Previously reported mechanisms are related to the up-regulation of immunosuppressive IL-10 [52], G-protein coupled receptors (GPRs), specifically GPR41 [53], and inhibition of multiple cellular immune mediators such as toll-like receptor engaged IL-12/23p40 [54], nuclear factor (NF)-κB [55], and histone deacetylase [53, 56]. IBD including both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease are a typical chronic relapsing inflammatory disease caused by genetically related anti-inflammation deficiency [57]. It is believed that the sensing capacity of anti-inflammatory mediators such as butyrate is impaired in IBD patients. However, supplementing higher levels of butyrate dense dietary fibers could counteract the severity of these syndromes to some degree [55, 58, 59].

Phytochemicals and gut microbiome

Only 5–10% of phytochemicals are absorbed in the small intestine, while the remaining 90–95% of phytochemicals are transformed by the resident colonic microbiota [60]. The microbiota yields highly bioavailable metabolites from these phytochemicals. The metabolism and absorption of phytochemicals may have potential systemic health effects on the host (i.e., cardioprotective [61, 62], and protection against glucose toxicity [63]). These systemic health effects are partly due to an increase of polyphenols in the diet, which has been linked with prevention of diverse chronic diseases [i.e., metabolic syndrome [64, 65]; will be further discussed below]. Last, unabsorbed dietary phytochemicals can directly modulate the microbiota. For instance, phenolic compounds from tea leaves inhibited growth and adhesion of Clostridium spp., E. coli, and S. typhimurium [66].

Preventive potentials of phytochemicals against diseases, in the context of the microbiome, have been receiving great attention recently. For example, when analyzing the short-term rice bran consumption impact on colorectal cancer in humans, Brown et al. found a 28-fold and 14.5-fold increased detection of the citrus related phytochemicals in stool metabolite profile, which were hesperidin and narirutin, respectively [67]. Hesperidin has shown to down-regulate inflammatory markers in induced carcinogenesis in mice [68]. Hence it is reasonable to expect that hesperidin resulting from gut microbiota-mediated metabolism (e.g., rice bran) may elicit beneficial effects against inflammation-related diseases (e.g., colorectal cancer). Table 2 shows categorized phytochemicals and their origins.

Flavonoids and their impacts on gut microbiome

Flavonoids are major components of many plant-based foods and beverages. Many mice studies focused on exposure to flavonoids’ capability to positively alter the Firmicutes/Bacteroideses ratio in mice with metabolic syndrome symptoms (e.g., obesity, and diabetes). For instance, Cheng et al. looked at the impact of Cyclocarya paliurus herbal tea, which contains high amounts of flavonoids, on obesity-related metabolic disorders [69]. Cyclocarya paliurus flavonoids (CPF) decreased the Firmicutes/Bacteroideses ratio and Proteobacteria at the phylum level while fecal microbial diversity was improved, indicating CPF influence on the microbial community and between host and microbe provide beneficial effects. Additionally, an abundance of Prevotella was detected, which is beneficially involved in glucose metabolism [70] and fermentation of amino acids [71], suggesting dietary flavonoids could produce protective and therapeutic effects on high-fat induced obesity via modulation of the microbiome [69].

Similarly, two short-term mice studies focused on flavonoid modification of the gut microbiome in non-disease specific states. Wankhade et al. analyzed blueberry consumption, finding significant modifications in both α-diversity and β-diversity [65]. Specifically, the Firmicutes/Bacteroideses ratio, Tenericutes, and Deferibacteres were decreased at the phylum level. Interestingly, the sex was a significant factor at the genus level; metabolic pathways (i.e., fatty acid metabolism, lipid metabolism) were significantly different in blueberry-fed male mice, and not in blueberry-fed female mice. While this study does suggest the influence of flavonoids from blueberry on gut microbial α-diversity and β-diversity in male mice, it is less clear why there was no effect on the female mice [65].

The other short-term mice study looked at black raspberry effect on the colonic microbiome. Black raspberries improved the Firmicutes/Bacteroideses ratio, and high amounts of polyphenols ellagitannins (i.e., urolithins) and anthocyanins were identified in colon tissue and plasma. Luminal Clostridium was significantly decreased after intervention, which is possibly due to pathogenic Clostridium (i.e., Clostidium perfingens, Clostridium difficile). Dietary black raspberries ultimately increased mucosal microbial composition, via reduction of luminal Clostridium, on the luminal microbiota [64].

Supporting the potential therapeutic role of flavonoids, Petersen et al. utilized long-term strawberry supplementation for microbiome modification in diabetic mice [72]. Microbial composition was significantly altered at the phylum and genus levels in both α-diversity and β-diversity, by decreasing Verrucomicrobia and Bifidobacterium in diabetic mice. Additionally, there were multiple significantly predicted functional metagenomic profiles identified through the PICRUSt (i.e., lipid biosynthesis proteins, insulin signaling pathway, and phosphatidylinositol signaling pathway), indicating a correlation between these pathways and bacterial abundance [72].

Another study looked at the effect of long-term supplementation of dietary flavonoid isoquercetin and soluble fiber inulin effects on mice that were fed a high-fat diet (to induce metabolic disorders). Tan et al. found that mice receiving both isoquercetin and inulin supplementation had slower weight gain, improved glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity, reduced hepatic lipid accumulation, adipocyte hypertrophy, circulating leptin and adipose fibroblast growth factor 21 levels. Interestingly, the compared groups receiving isoquercetin or inulin independently had no significant results. This suggests inulin changes the microbiome composition through its prebiotic effects, enhancing the metabolism and absorption of the flavonoid isoquercetin to have beneficial effects on the prevention of metabolic syndrome development with high-fat diets [73].

An abundance of future studies is needed to fully understand broad impacts of flavonoids on the gut microbiome. While many of these studies identified microbial composition and disease states, they found were mainly focused on the Firmicutes/Bacteroideses ratio, and the metabolic disease state. More studies are needed to identify the alterations of other microbial strain due to flavonoid intervention, and how they potentially impact disease states. Additionally, more research is needed to identify the potential impact of flavonoids on other diseases, such as cancers and inflammation. Long-term studies would further help solidify sex-specific changes on the microbiome in flavonoid interventions, as there are currently no long-term studies published in this area. Lastly, many of these studies failed to isolate the effects of flavonoids from whole fruit and vegetable consumption. Perhaps a single flavonoid may have difficulty making a significant effect, making it difficult to determine if the results are due to the phytochemical metabolite or due to the beneficial effects of fiber. As noted above, fiber has a significant impact on the modulation of the microbiome, and without this separation it could prove difficult to understand the significant effect of the phytochemical.

Carotenoids and their impacts on gut microbiome

Two primary research articles reported implications of carotenoids on the microbiome, where both analyzed the effect of increased serum carotenoid concentrations on the gut microbiome. High serum carotenoids are associated with decreased risk of chronic diseases [74], and contribute to gut microbiome health. While carotenoids are found in multiple plant-based dietary sources (e.g., carrots), Ramos et al. analyzed the carotenoid source of Tucumã oil and its effect on microbial diversity and SCFA production in cows. Carotenoids from Tucumã oil resulted in a lower abundance in Fibrobacter and Rikenellacea RC9 gut group, and enriched Pyramidobacter, Megasphaera, Anaerovibrio, and Selenomonas. These results suggest the use of Tucumã oil as a catenoid source and shows favorable shifts in gut microbiome health [75]. Comparatively, a long-term randomized control study in humans analyzed the relationship between colonic mucosal bacteria and serum carotenoid concentrations. Djuric et al. found that colonic mucosal bacteria were associated with serum carotenoid concentrations at baseline, and long-term exposure had no significant effects. Indicating the need for increased research on long-term exposure to better understand the effect of dietary change maintaining a beneficial microbial change. It was identified, however, that 11 operational taxonomic units were associated with higher serum carotenoid levels. Factors affecting the level of carotenoid levels included body mass index, smoking, and dietary intakes (representing 12% of the total variance in carotenoid levels). These results further suggest the impact of multifaceted factors (i.e., behavioral and metabolic factors) on the gut microbiota’s capability for carotenoid absorption [74]. Further research is needed on carotenoids and effects on microbiota diversity and impacting disease states in hosts, as only these two articles were identified in the search.

Glucosinolates and their impacts on gut microbiome

Glucosinolates are sulfur-containing compounds profoundly present in cruciferous vegetables. Thus far only one study examined effects of glucosinolates on the gastrointestinal microbiota which is somewhat unexpected given their widely known benefits against chronic diseases (i.e., cancers [76,77,78]). Specifically, broccoli and cabbage are good sources of glucosinolates. Kaczmarek et al. analyzed the effects of broccoli on the gut microbiota via a short-term randomized controlled feeding study in healthy adult subjects. β-diversity alterations indicated that bacterial communities were impacted by broccoli feeding; Firmicutes abundance was decreased by 9% while Bacteroides abundance was increased by 8%. The strongest associations between bacterial relative abundance and glucosinolate metabolites were seen in participants with a body mass index < 26 kg/m2. Additionally, broccoli consumption significantly altered a few key metabolic pathways: endocrine system, transport and catabolism, and energy metabolism [79]. Clearly, further studies are warranted in the context of the disease preventive potential of cruciferous vegetables through gut microbiome modulation, particularly considering that gastrointestinal microbiota can metabolize glucosinolates into isothinocyanates (ITCs) [80]. Also, additional mechanistic studies are needed to explain different responses to glucosinolates in participants with higher body mass index.

Allicins and their impacts on gut microbiome

Allicins are organic sulfur phytochemicals that are particularly found in garlic [81]. One short-term randomized control study examined the effects of garlic extract on gut microbiota, inflammation, and cardiovascular markers (e.g., blood pressure, pulse wave velocity, and arterial stiffness). Reid et al. found that aged garlic, converted to the vaso-active component S-allylcysteine, inccreased Lactobacillus and Clostridia. Additionally, blood pressure was significantly reduced by 10 ± 3.6 mmHg systolic, and 5.4 ± 2.3 mmHg diastolic. Central blood pressure and arterial stiffness were significantly reduced, showing improvements in overall hypertension. These findings may provide hints between gut microbiome modulation and cardiovascular health although a causal relationship is still not clear [82]. As shown in this study, allicins may have beneficial cardiovascular effects; however, this short-term feeding study is the only evidence demonstrating impacts of allicins on the gut microbiome. Similar to other groups of phytochemicals, long-term feeding in addition to mechanistic/functional validation are needed; in addition, in order to uncouple with effects of fibers, it will be informative to explore if the garlic-induced gut microbiome modulation can be recapitulated with isolated allicin exposure.

Micronutrients and microbiome

A multidirectional relationship lies between the host and its microbiome. Although, as aforementioned, diet significantly impacts the gut microbiome, gut microbiota per se also play a role in human metabolic functions [83]. Furthermore, the microbiome may alter the host’s absorption of various dietary nutrients and, thereby, indirectly impact micronutrient physiology [84]. Specifically, some microbial strains synthesize vitamins and cofactors, and evidence suggests that microbial metabolites can affect metabolic and physiological pathways of micronutrients in the human body [85, 86]. In addition, production of vitamins and cofactors can provide essential nutrients to colonocytes, promote competition with pathogenic organisms, and modulate immune responses [87]. Because bacteria alter the efficiency of bile acids to emulsify dietary lipids and form micelles, the microbiome potentially influences the absorption of lipid-soluble vitamins as well [88]. With consideration for luminal nutrient effects on the microbiome and microbial effects on host nutrition status, it is reasonable to believe that identification and manipulation of microbial interactions with hosts could be pivotal to human health.

Numerous factors, including physiochemical properties of foods, nutrient availability, colonic transit time, and age of host may modulate dietary effects on the colonic microbiota [89]. Substrates that are not defined as “prebiotics”, such as phytochemicals, potentially alter microbial composition and function; vitamins and minerals are also examples of these substrates, yet they are not well-recognized or well-understood regarding their effects on the gut microbiome [90]. This may be partially due to the fact that most vitamins are absorbed in the upper small intestine, which results in low concentrations of vitamins or minerals reaching the distal parts of the gastrointestinal tract [90]. Nevertheless, studies have found micronutrient-induced changes in the mammalian gut microbiome, and modulation by vitamins and minerals warrants further investigation [85]. In fact, it was reported that several micronutrients have potential to alter gastrointestinal function, immune response, and, as a result, microbial populations [85, 91].

It is estimated that more than three billion people worldwide suffer from micronutrient deficiencies, predominantly vitamin A, iron, and zinc [91]. Disease states (e.g., malnutrition) may alter microbiome-mediated transport, metabolism, and synthesis of cofactors and vitamins [91]. Therefore, interference of microbiota function by micronutrient deficiency could explain the relationship between dysbiosis and malnutrition [92]. Few existing studies have examined the transportation of vitamins between the microbiota and intestine or the impact of luminal vitamins on the microbiota (host-microbe-metabolic axis) [92, 93]. Understanding the influence of low micronutrient supply on microbiota development, composition, and metabolism is an integral part of implementing new strategies to overcome deleterious effects of malnutrition [92].

Mapping of metabolic relationship

A microbiome has approximately 150-fold more genes than the human genome [94]. Using high-throughput technologies such as next-generation sequencing and mass spectrometry–based metabolomics, researchers are able to sequence the metagenome of the microbiome and associate this information with the genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics and metabolomics of the host [94]. Mapping of human and microbe-derived enzymes to gut metabolic pathways has revealed that gut microbe-derived enzymes are essential components of various human pathways [83]. A total of 518 enzymatic reactions were shared between host and gut-bacterial species [83], suggesting significant cross-talk between the host and microbiota. Furthermore, mapping of known and predicted enzymes to canonical human pathways resulted in identification of 48 pathways that have at least one bacteria-encoded enzyme [83]. Bacterial communities contribute to human gut metabolism by complementing enzymes that are not encoded by the human genome but are essential for digestion and metabolism [83]. Most of these pathways are involved in metabolizing dietary nutrients, including cofactors and micronutrients [83]. Thirty exclusively microbe-derived enzymes complement vitamin/cofactor metabolic pathways, which underscores the dependency of human pathways on microbe-derived enzymes [83]. Microbes not only complement, but also supplement some of the enzyme functions that are common to both human and gut microbiome [83]. Further support is provided by the findings of a meta-genome analysis of the human gut microflora, which revealed the presence of Clustered Orthologous Groups of proteins involved in production of essential vitamins [95, 96]. Most of the production and absorption of microbial vitamins takes place in the colon; however, the microbiome may contribute to maintaining systemic levels and minimizing deficiency effects [95, 96]. Microbiome multi-omics analyses coinciding with host omics datasets will be important for revealing the microbiome’s role in human health [94]. Unbiased and untargeted omics approaches could unveil the involvement of vitamins and minerals within the interrelationship of the host and microbiome [94].

Vitamins

Of the essential micronutrients, microbial synthesis of vitamin K and B vitamins had the greatest body of research regarding effects on host systemic status. There is also evidence of microbial modulation of colonocyte nutrient absorption that potentially influences host nutrition status [84, 88]. In contrast, little is known regarding effects of vitamin supplementation on the gut microbiome, and the relationship between micronutrient deficiencies and dysbiosis is yet to be elucidated.

Vitamin B

Intestinal microbiome may be a primary source of B vitamins [97]. It is known that these vitamins modulate host’s epigenome [98]. Because the vitamins produced by the microbiota can result in epigenetic changes in host cells, they may play a significant role in modulating host gene expression [98]. Of the 8 B vitamins, 7 have colonic bacterial sources, and a human population with abnormal intestinal microbiota may have unexpected B vitamin deficiencies that are unrelated to food consumption [97], reinforcing the importance of gut microbiome in B vitamins metabolism and thus host health.

Vitamin B1 (thiamine) is an essential cofactor for organisms. Humans acquire most vitamin B1 through their diet [99]; however, evidence indicates that bacterial-derived vitamin B1 can be absorbed into human colonocytes, which may contribute to colonic vitamin B1 status and affect systemic status. A study published in 2017 investigated vitamin B1′s role in the gut utilizing Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron as a model gut microbe [99]. RNA sequencing revealed global downregulation of vitamin B1 and amino acid biosynthesis, glycolysis, and purine metabolism in the presence of vitamin B1, and expression of the major biosynthetic operon was upregulated under vitamin B1-deficient conditions [99]. Further investigation using genetic mutants suggested thiamine biosynthesis and transport is critical for growth when vitamin B1 is deficient [99]. The ability of microbes to transport, synthesize, and compete for vitamin B1 may impact the structure and function of the microbiome during shifts in luminal availability of vitamin B1. Gut microbes that are wholly dependent on vitamin B1 transport, such as members of the genus Alistipes and many members of the Bacilli, are predicted to be adversely affected by deficient conditions [99]. In a study of Crohn’s disease (CD) patients, microbial genes for pathways involved in biosynthesis of vitamins B1, B2, B9, and B12 were decreased during exacerbation; [100]. The study suggested that intestinal abundances of vitamin B1, B2, B9, and B12 could be involved in CD exacerbation and inflammation associated with dysbiosis [100]. Therefore, manipulating the presence or concentration of vitamin B1, and possibly of other water-soluble vitamins, could be an effective method for treating or preventing dysbiosis [99].

Free absorbable and protein-bound forms of vitamin B2 are synthesized by the human microbiota, but the uptake of vitamin B2 into colonocytes is concentration dependent; the higher the luminal concentration, the lower the uptake, and vice versa [91]. As a result, the systemic effects of vitamin B2 production in the lumen may be mediated. Furthermore, genomic and functional analysis of one gut microbe, Romboutsia ilealis CRIBT, revealed genes for de novo purine and pyrimidine synthesis, as well as for production of coenzymes NAD and FAD via salvage pathways from vitamin B2 and B3 [101]. R. ilealis CRIBT relies on these pathways or exogenous sources for the supply of precursors, mainly in the form of B vitamins, suggesting that luminal B vitamin availability may alter microbiome function and composition [101]. Vitamin B2 affects the growth of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, which has a specialized use of vitamin B2 as an extracellular electron transporter, allowing it to tolerate limited levels of oxygen [90, 101]. The stimulation of F. prausnitzii growth by exposure to vitamin B2 may be a function of this vitamin in microbiome-modulation that could be of clinical interest [90]. A first pilot open-label study with vitamin B2 (100 mg vitamin B2/day) showed an increase in Faecalibacterium and a reduction in E. coli in most participants [101]. In addition, multiple articles suggest that a double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled “Ribogut” trial was approved in 2018. The trial was to examine the effects of vitamin B2 on the gut microbiota composition of healthy volunteers administered 50 or 100 mg vitamin B2/day for 14 days; however, no results have been published [101]. Further vitamin B2-microbiome studies may present new possibilities for vitamin combinations as supplements for prevention of human diseases through microbiome modulation [90].

It was suggested that vitamin B5 (pantothenic acid) is potentially supplied by normal intestinal bacteria more so than by natural food sources [97]. However, the relationship between the microbiome and vitamin B5, as well as vitamin B3 (niacin) and B6 (pyridoxine), is otherwise unclear. However, the human microbiota contains enzymes that depend on vitamin B6 [91]. Certain bacteria or the host may contribute the vitamin B6 needed for aminotransferase metabolism in bacteria [91]. Virulence and motility of Helicobacter pylori depend on the presence of functional enzymes important for bacterial de novo vitamin B6 synthesis [91].

Humans cannot produce vitamin B7 (biotin) and, therefore, evidently depend on dietary intake or the intestinal microbiota to maintain healthy levels [53]. However, no pathways for how the microbiome affects systemic status have been elucidated.

Bacteria commonly found in the colon can produce vitamin B9 (folate) [93]. Although vitamin B9 is primarily absorbed in the small intestine, absorption does occur to some extent in the colon as well [93]. Vitamin B9 production by intestinal microbiota can modify the effects of vitamin B9 ingested in the diet and has already been considered in studies of diet and colon cancer risk [93]. However, it is still questionable whether high vitamin B9 production will result in higher absorption because administration of high-producing strains results in higher fecal vitamin B9 concentrations [91]. Nevertheless, radiolabeled vitamin B9 precursor (p-aminobenzoic acid) originating in the colons of rats resulted in radiolabeled vitamin B9 within various tissues. More research is needed to elucidate whether microbiota-derived vitamin B9 affects systemic folate status [91].

Vitamin B12 (cobalamin) is synthesized exclusively by bacteria and archaea. Although it is frequently argued that microbiome-derived vitamin B12 is a source for humans, experimental data shows this is not the case because colonic vitamin B12 is not bioavailable due to the lack of required enzymes and receptors in the colon [91]. Despite the lack of absorption, vitamin B9 and B12 regulate microbiota gene expression and may control genomic interactions between the microbiome and host [91]. The gut microbiome has vitamin and mineral requirements for growth and proliferation, and studies have found several pairs of organisms with vitamin synthesis pathway patterns that complement each other, implying a vitamin-dependent cross-feeding between microbes for growth [88]. B12 production by Eubacterium hallii and the interdependent production of propionate by Akkermansia muciniphila demonstrates this mutualistic symbiosis [102]. In a study surveying over 300 sequenced microbiota-derived bacterial strains, 83% of the strains were shown to have enzymes dependent on vitamin B12 as a cofactor [91]. Most of these species lack genes required to synthesize vitamin B12 de novo and, therefore, rely on transport to meet their requirements [91]. Gut microbial species consequently compete with other species and the host for dietary vitamin B12, indicating that luminal vitamin B12 is an important nutrient for the gut microbiome [91, 93]. Furthermore, B vitamin production by intestinal bacteria mediates or modifies the effects of other ingested nutrients, which partly explains the heterogeneity in the results of the studies investigating these nutrients to date [93]. There is now strong evidence that water-soluble vitamins synthesized by the microbiota contribute to interactions with the host [91], but specific mechanisms for cross-talk require further investigation.

Vitamin C and vitamin E

Antioxidants, including vitamin C, are being explored as new targets for the treatment of dysbiosis, but few reports are available regarding vitamin C in relation to the microbiome [103]. One study explored vitamins C and E, as part of an antioxidant blend with tea polyphenols, lipoic acid, and microbial antioxidants in early-weaned piglets [104]. Early weaning caused oxidative stress (represented by malondialdehyde, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals) and changes in intestinal microbiota, including significantly decreased total bacteria, Lactobacillus, and Bifidobacterium counts, and increased E. coli counts [104]. In contrast, antioxidant status (represented by antioxidant enzymes) demonstrated a positive correlation with Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, and a negative correlation with E. coli [104]. Therefore, oxidative stress was directly related to changes of gut microbiota, and vitamin C and E, as part of an antioxidant blend, affected microbiome composition in weaned piglets [104]. Dietary overnutrition and metabolic syndrome may cause overgrowth of Gram-negative bacteria in the gut that cause inflammation, impaired gut function, and endotoxemia [105]. A review paper published in 2019 concluded that, whereas endotoxemia depletes vitamin C and impairs vitamin E trafficking, high vitamin C intake has the ability to restore gut-liver functions and antioxidant status [105].

Vitamin A and vitamin D

In contrast to the B vitamins, gut microbiota do not synthesize carotenes, but, as dietary carotene may be adsorbed to fibers, bacterial digestion of fibers potentially liberates carotene for absorption into colonocytes [91]. Therefore, the microbiome potentially affects host vitamin A status.

It is well known that vitamin A or vitamin D deficiency significantly affects the immune response [91]. As is vitamin D, vitamin A is involved in the induction of antimicrobial gene expression; consequently, retinoic acid is likely responsible for adequate immune response and barrier function of the intestinal mucosa against pathogenic bacteria [91]. Impaired response and decreased mucin and defensin expression may allow penetration of the intestinal barrier [91]. The total amount of bacteria (including E. coli) in the rat intestinal tract was increased by vitamin A deficiency, and the prevalence of Lactobacillus spp. was decreased in the intestinal segments of the jejunum, ileum, and colon [106]. Similar reductions of these species were found in the small intestines of vitamin A deficient mice, along with a reduction in segmented filamentous bacteria, but, in contrast to rats, total bacteria were reduced in deficient mice [106]. Overall, mechanistic support for how vitamin A deficiency leads to changes in intestinal bacterial populations is lacking [106].

Vitamin D and its receptor [vitamin D receptor (VDR)], are known as regulators of microbiome and health [107]. Specifically, conditions such as low levels of vitamin D or inactivating polymorphisms in VDR, have been implicated in the development of inflammatory and metabolic disorders [108, 109]. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with dysbiosis, and supplementation has the potential to modulate the gut microbiome [108]. Studies in 1-month old infants and in ages 3–6 months have found influences of vitamin D on key bacterial taxa [110, 111]. In 1 month old infants, Bifidobacterium spp. and C. difficile appeared to have negative correlations with vitamin D consumption, whereas B. fragilis presented a positive linear relationship [110]. Lower proportions of Clostridiales were seen in 3 to 6-month-old breastfed infants, and cord blood vitamin D was linked to increased Lachnobacterium, but decreased Lactococcus [111]. In addition, Vitamin D supplementation has a positive effect on inflammatory bowel disease and cystic fibrosis patients through the modulation of the microbiome [108]. When it comes to mechanisms, vitamin A and D play roles in the induction of antimicrobial gene expression and affect intestinal immune and barrier function that plays a role in suppression of microbial invasion into the epithelium [90, 112, 113]. More specifically, vitamin D induces expression of antimicrobial peptides (defensin and cathelicidin) and maintains adequate TJ formation [113]. Additionally, VDR knockout mice and mice fed a vitamin D-deficient diet exhibited altered microbiota composition [114], supporting a notion that vitamin D may promote health via gut microbiome.

VDR is absent in prokaryotic cells, so any effects of vitamin D on microbiota must be through indirect effects of the host that alter the microbiome [91]. Variations in the human VDR gene shapes the gut microbiome at the genetic level [107]. Conditional knockout of intestinal epithelial VDR leads to dysbiosis, particularly altered bacterial abundance; VDR knockout mice exhibit a decrease in Lactobacillus and an increase in Clostridium and Bacteroides [107]. Although VDR expression modulates the microbiome, some gut microbiota have the ability to enhance VDR gene expression in intestinal epithelial cells [115]. Genome-wide association analysis identified variations in the human VDR gene and other host factors that influence gut microbiota [116]. Specific associations were identified between overall microbial and individual taxa at multiple genetic loci, including the VDR gene [107]. In summary, studies have demonstrated that vitamin D and variants of VDR have a relationship with the gut microbiome.

With evidence that vitamin D deficiency results in dysbiosis, vitamin D supplementation may be an effective modulator of the microbiome [86, 97, 116]. With oral intake of vitamin D3, Bacteriodetes and Firmicutes were the dominating phylum and less Proteobacteria were recorded in the mucus of the upper gastrointestinal tract than in the lower [86]. Vitamin D3 also decreased the cell numbers of Helicobacter spp. in the pylori-positive subgroup [86]. Vitamin D3, however, did not have an effect on the microbial population of the lower gastrointestinal tract [86]. Because dysbiosis has become epidemic in parallel with vitamin D deficiency, another study examined the possible link between vitamin D deficiency and dysbiosis in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patients [97]. It was expected that vitamin D supplementation would improve IBS and induce weight loss, but with two years of careful vitamin D supplementation, there was no improvement in patient-reported IBS symptoms and no weight loss [97]. To test the hypothesis that secondary vitamin B5 deficiency impeded healthy microbiome composition, B100 (100 mg of all B vitamins, except 100 μg of B12 and vitamin B7 and 400 μg of vitamin B9) was added to vitamin D supplementation [97]. When B100 was added to vitamin D supplementation, differential results were more prominent [97]. Three months of vitamin D and B100 resulted in improved sleep, reduced pain, and resolution of bowel symptoms that suggested a return of the four phyla Actinobacteria, Bacteriodetes, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria that make up the normal human microbiome [97]. Based on patient-related IBS symptoms, the “healthy four” bacterial phyla did not return with just vitamin D but did appear with both large doses of vitamin D and B vitamins in a full complement of 8 [97]. Therefore, the study suggests that vitamin D supplementation alone does not positively impact the gut microbiome.

Vitamin K

Research has demonstrated that gut microbiome synthesizes vitamin K2, but clear understanding as to its bioavailability is lacking [91]. Absorption of vitamin K generally takes place in the small intestine and requires bile salts and pancreatic enzymes, which are both absent in the colon [91]. However, humans on low vitamin K diets for 3–4 weeks did not develop vitamin deficiency, whereas subjects treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics showed a significant decrease in plasma prothrombin levels [88], indicating potential role(s) of gut microbiome in vitamin K metabolism. In line with this, uremia in chronic kidney disease patients can affect absorption of nutrients due to changes in the patient’s gut microbiome, as evidenced by altered SCFA concentrations and reduced serum vitamin K [117]. It is possible that gut microbiome alterations due to uremia result in lower production and absorption of vitamin K and, thus, higher prevalence of deficiency [117]. In summary, vitamin K is consumed through dietary intake, but gut bacteria may also affect systemic vitamin K status [88]. However, exact mechanism(s) underlying these interactions and factors influencing vitamin K bioavailability are to be elucidated.

Overall, despite assumptions regarding microbiome and vitamins, little is known about the influence of the human microbiome on systemic micronutrient status. Note that literature has, all together, not discussed many of the B vitamins, vitamin C, or vitamin E in relation to the microbiome. Clearly, the lack of primary research experiments underscores the need for further research.

Minerals

At the intestinal level, microbiota affect absorption of calcium, magnesium, and iron [84]. Iron transporters are present in the cecum and right colon, and, in the presence of prebiotics that promote growth of bacteria to produce propionate, iron absorption increases [91]. Luminal minerals, including calcium, iron, and other micronutrients, may also have microbiome-modulating effects as well [90]. As discussed, bacteria present different growth requirements, and thus have selective advantages and disadvantages according to environment. Specifically, a study examined nutrient transport reactions (i.e., exchange reactions) in silico to understand effects of gut nutrients on bacterial growth using four bacteria species [118]. In the study, environmental exchange of carbon dioxide, copper, potassium, magnesium, manganese, sulfate, zinc, and ferrous (Fe2+) iron were found to be essential reactions for cell growth shared by the four bacterial species.

Iron

Iron (Fe) is an essential nutrient for many microbes, and it has been recently demonstrated that the gut microbiome has the potential to influence iron uptake and storage by modulating iron transport proteins [119]. Iron supports some microbial growth, which may include both normal and pathogenic strains [112]. Bacteria use different forms of iron as cofactors [101]. As multiple transporters involved in the transport of iron compounds are predicted, it is possible that uptake of iron provides a competitive advantage to microbes that are dependent on iron for respiration and other metabolic processes [101]. In particular, Lactobacilli seem to depend on iron, and it has been recently shown that iron-deficiency anemia is related to a depletion of Lactobacilli [91]. This may explain the reduction of Lactobacilli in iron-deficient microbiomes [91]. Recent studies using animal models of dietary iron deficiency have shown decreased levels of Bacteriodes spp. and Roseburia spp./Eubacterium rectale, and increased levels of Lactobacilli and Enterobacteriaceae [119]. In rodent models, iron deficiency lead to a significant reorganization of the microbiota composition with a decrease in the microbial diversity [106]. Interestingly, repletion of iron-deficient rats with iron sulfate (FeSO4) caused a partial restoration of the microbiota but decreased numbers of Enterobacteriaceae and Lactobacillus/Pediococcus, Leuconostoc spp. [106]. A similar study in mice also found that iron deficiency decreases Xylanibacter, Ruminococcaceae, and Prevotella and increases Prevotellaceae,, but iron repletion only partially restored microbiota diversity [106]. Feeding iron in the form of heme to mice increased Bacteriodetes and decreased Firmicutes [106].

It is clear that dietary components, such as iron, influence host gut microbiota composition and metabolism [119]. A large body of evidence suggests that poorly bioavailable iron can stimulate the growth and virulence of pathogenic microbes [119]. Studies in both humans and animals have reported iron supplement-induced changes in microbiome composition, including increases in Bacteroides spp. and Enterobacteriaceae, decreases in Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli, and an expansion of opportunistic pathogens such as Salmonella, E. coli, and C. difficile [119]. When Gallus gallus (broiler chickens) were fed an iron biofortified diet versus a diet with poorly bioavailable iron, no significant changes in phylogenetic diversity was observed [119]. However, there were significant differences in microbiota composition, with the iron biofortified group harboring fewer taxa that participate in iron uptake, greater abundance of bacteria involved in phenolic catabolism, and greater abundance of beneficial butyrate-producers [119]. Additionally, improvements of iron bioavailability led to decreased cecal iron availability for bacterial utilization [119]. Significant remodeling of the gut microbiota occurred in animals receiving clinically-relevant iron-biofortified diet [119]. Not only was the biofortified diet not associated with an increase in dysbiotic or pathogenic microbial load, but this group harbored more SCFA-producers and other beneficial bacteria and fewer bacterial genes encoding infectious diseases compared to the mildly iron-deficient group [119].

Zinc

In addition to iron, the interrelations of zinc status and the microbiome have been studied using animal models. A study using chicken as a model found that zinc deficiency resulted in remarkable changes in the microbiota, including metabolic changes, reduced output of SCFAs, and a subsequent reduction in zinc bioavailability [91]. Furthermore, mice fed a high zinc diet (1000 mg/kg diet) showed decreased microbial diversity with shifts in bacterial species, while an adequate zinc (29 mg/kg) or low zinc (0 mg/kg) diet did not [106]. Zinc-supplemented mice were also more susceptible to C. difficile infection [106]. However, other studies have found that high rates of trace mineral supplementation in swine and poultry altered microbial colonization of the gut, resulting in improved gut health [91]. More specifically, supplementation of zinc increased gram-negative facultative anaerobic bacterial groups, the colonic concentration of SCFAs, as well as overall species richness and diversity [91]. For example, supplementation with high levels of zinc increased Lactobacillus in the gut microbiome of weaned pigs and resulted in favorable effects on development and metabolic activity of the intestinal microbiota [91, 120]. In contrast, trace mineral treatment in cattle had no effect on phylum and family fecal microbial relative abundance, with the exception of bacteria in phylum Spirochaetes and family Spirochaetaceae; however, fecal abundance may not be indicative of gut microbiota composition [120].

Selenium

Selenium (Se) status correlates with higher diversity of gut microbiome in mice, and specific phylotypes are altered in the order Bacteriodales and Firmicutes [106]. A study in 2011 assessed the effect of dietary Se on the composition of mouse microbiota by subjecting mice to a Se-deficient diet and diets supplemented with 0.1, 0.4, or 2.25 ppm of Se in the form of sodium selenite [121]. After 8 weeks, Se status was examined by analyzing the levels of SelP, the main selenoprotein in plasma of mammals [121]. SelP decreased dramatically in mice fed the Se-deficient diet, whereas the differences between mice fed the other diets were minimal [121]. Effects were independent of germ-free, conventionalized, and colonization conditions. Se supplementation (at all doses) increased microbiome diversity [121]. Relative proportions of major taxonomic groups were not different; however, specific phylotypes were affected [121]. For example, some phylotypes of Bacteriodales increased in response to Se, whereas others decreased [121].

The intestinal microbiota may be sensitive to changes in trace element levels; therefore, gut colonization may influence trace element status, either through competition for certain elements or modification of food absorption or digestion [121]. Experimentation revealed Se levels in the liver, kidney, and spleen of mice were sensitive to dietary Se, whereas concentration in brain and testes did not differ with Se intake [121]. Despite the possibility of Se-induced changes in other nutrient statuses, analysis of trace elements, including Mn, Fe, Zn, Mo, Cu, and As, did not reveal statistically significant differences between different Se diets [121].

Additionally, in 2018, four experiments using mice models investigated the effects of Se content in diet on the gut microbiome [122]. In mice with only differential Se supplementation, the overall richness of the gut microbiome was not altered, but different Se intakes induced changes in the compositions of the gut microbiome [122]. Dorea levels were increased when diet was Se-deficient (< 0.01 mg/kg diet), and overgrowth of Dorea has been proposed to have adverse health effects [122]. In contrast, increases in Turicibacter and Akkermansia and decreases in Mucispirillum were detected in mice supplied with supranutritional Se (0.40 mg/kg diet) when compared to Se-sufficient (0.15 mg/kg diet) [122]. Research suggests these alterations to the microbiome and, therefore, Se supplementation may have health benefits [122]. To bypass the effects of Se itself and determine the effects of Se-induced microbiota modulation, transplantation of fecal microbiota from different Se-supplied donors was investigated in mice and showed varied effects on intestinal barrier status and immune response [122]. Additionally, gut microbiota from Se-supplemented fecal donors showed resistance against DSS-induced colitis and an increased survival rate of 100% compared to 60% in a Se-deficient fecal transplant group [122]. Mice given fecal transplants from sufficient or supranutritional Se-supplied donors were also more resistant to Salmonella typhimurium compared to Se-deficient donor fecal transplanted mice, supported by decreased S. typhimurium load in the tissues, greater barrier function, and less intestinal inflammation [122].

Se and selenoproteins may impact inflammatory signaling pathways implicated in the pathogenesis of IBD [123]. In particular, Se status impacts two transcription factors, NF-κB and peroxisome proliferator activated receptor (PPAR)-γ, which are involved in activation of immune cells and are implicated in various stages of inflammation and resolution [123]. The relationship of Se, NF-κB, and PPAR-γ in relation to the gut microbiome and gut inflammation may provide alternative therapy methods for IBD [123]. The literature indicates that mice have been utilized in multiple studies to elucidate the effects of Se on the gut microbiome [123]. However, no clinical trials have been conducted to understand the implications of selenium-induced changes to the human microbiome profile.

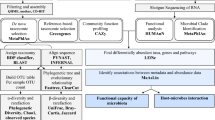

The above findings give promising evidence that phytochemicals, vitamins, and minerals alter the microbiome. This review presents well-established beneficial effects of fiber and SCFAs on the host microbiome and suggests a symbiotic relationship between the microbiome and host that is mediated by diet (Fig. 1). Furthermore, adequate amounts of phytochemicals, vitamins, and minerals may pose therapeutic or preventative effects against diseases. There are obvious limitations in the amount of literature investigating direct influences of phytochemicals, vitamins, and minerals on the microbiome. Each individual phytochemical, vitamin, and mineral lacks a large body of evidence to support controlled modification of the gut microbiome for health benefits by oral consumption/supplementation. A thorough understanding of other factors that regulate effects (e.g., sex differences, synergistic effects, mechanisms) is also lacking. Moreover, there are limitations in translating animal models to human significance, and the available results are conflicting as to whether supplements disrupt or improve microbial diversity and richness.

The impact of the microbiome on host micronutrient status is also still controversial due to uncertainty regarding the absorption and metabolism of synthesized micronutrients in the colon. Despite the lack of quality support for specific pathways, it is evident that vitamins and minerals play a role in the multidirectional relationship between the microbiome and host. In the future, phytochemicals, vitamins, and minerals may be components of prevention and treatment measures taken to combat diseases linked to the microbiome. However, the interplay of the microbiome and each micronutrient is far from clear. The gap in the literature presents significant opportunity to explore micronutrient pathways within the host-microbe-metabolic axis.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Qin J, Li R, Raes J, Arumugam M, Burgdorf KS, Manichanh C, Nielsen T, Pons N, Levenez F, Yamada T, Mende DR, Li J, Xu J, Li S, Li D, Cao J, Wang B, Liang H, Zheng H, Xie Y, Tap J, Lepage P, Bertalan M, Batto JM, Hansen T, Le Paslier D, Linneberg A, Nielsen HB, Pelletier E, Renault P, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Turner K, Zhu H, Yu C, Li S, Jian M, Zhou Y, Li Y, Zhang X, Li S, Qin N, Yang H, Wang J, Brunak S, Dore J, Guarner F, Kristiansen K, Pedersen O, Parkhill J, Weissenbach J, Meta HITC, Bork P, Ehrlich SD, Wang J (2010) A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature 464:59–65

Mills RH, Vazquez-Baeza Y, Zhu Q, Jiang L, Gaffney J, Humphrey G, Smarr L, Knight R, Gonzalez DJ (2019) Evaluating metagenomic prediction of the metaproteome in a 4.5-year study of a patient with Crohn’s disease. mSystems 4:e00337-e1318

Koenig JE, Spor A, Scalfone N, Fricker AD, Stombaugh J, Knight R, Angenent LT, Ley RE (2011) Succession of microbial consortia in the developing infant gut microbiome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108(Suppl 1):4578–4585

Wu GD, Chen J, Hoffmann C, Bittinger K, Chen YY, Keilbaugh SA, Bewtra M, Knights D, Walters WA, Knight R, Sinha R, Gilroy E, Gupta K, Baldassano R, Nessel L, Li H, Bushman FD, Lewis JD (2011) Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science 334:105–108

Claesson MJ, Jeffery IB, Conde S, Power SE, O’Connor EM, Cusack S, Harris HM, Coakley M, Lakshminarayanan B, O’Sullivan O, Fitzgerald GF, Deane J, O’Connor M, Harnedy N, O’Connor K, O’Mahony D, van Sinderen D, Wallace M, Brennan L, Stanton C, Marchesi JR, Fitzgerald AP, Shanahan F, Hill C, Ross RP, O’Toole PW (2012) Gut microbiota composition correlates with diet and health in the elderly. Nature 488:178–184

Slavin JL (2005) Dietary fiber and body weight. Nutrition 21:411–418

Deehan EC, Duar RM, Armet AM, Perez-Munoz ME, Jin M, Walter J (2017) Modulation of the gastrointestinal microbiome with nondigestible fermentable carbohydrates to improve human health. Microbiol Spectr 5:1–24

El Kaoutari A, Armougom F, Gordon JI, Raoult D, Henrissat B (2013) The abundance and variety of carbohydrate-active enzymes in the human gut microbiota. Nat Rev Microbiol 11:497–504

Holscher HD (2017) Dietary fiber and prebiotics and the gastrointestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes 8:172–184

Van Rymenant E, Abranko L, Tumova S, Grootaert C, Van Camp J, Williamson G, Kerimi A (2017) Chronic exposure to short-chain fatty acids modulates transport and metabolism of microbiome-derived phenolics in human intestinal cells. J Nutr Biochem 39:156–168

Schulthess J, Pandey S, Capitani M, Rue-Albrecht KC, Arnold I, Franchini F, Chomka A, Ilott NE, Johnston DGW, Pires E, McCullagh J, Sansom SN, Arancibia-Carcamo CV, Uhlig HH, Powrie F (2019) The short chain fatty acid butyrate imprints an antimicrobial program in macrophages. Immunity 50(432–445):e437

Desai MS, Seekatz AM, Koropatkin NM, Kamada N, Hickey CA, Wolter M, Pudlo NA, Kitamoto S, Terrapon N, Muller A, Young VB, Henrissat B, Wilmes P, Stappenbeck TS, Nunez G, Martens EC (2016) A dietary fiber-deprived gut microbiota degrades the colonic mucus barrier and enhances pathogen susceptibility. Cell 167(1339–1353):e1321

Delcour JA, Aman P, Courtin CM, Hamaker BR, Verbeke K (2016) Prebiotics, fermentable dietary fiber, and health claims. Adv Nutr 7:1–4

Bang SJ, Kim G, Lim MY, Song EJ, Jung DH, Kum JS, Nam YD, Park CS, Seo DH (2018) The influence of in vitro pectin fermentation on the human fecal microbiome. AMB Express 8:98

Gibson GR, Roberfroid MB (1995) Dietary modulation of the human colonic microbiota: introducing the concept of prebiotics. J Nutr 125:1401–1412

Roberfroid M (2007) Prebiotics: the concept revisited. J Nutr 137:830S-837S

Gibson GR, Probert HM, Loo JV, Rastall RA, Roberfroid MB (2004) Dietary modulation of the human colonic microbiota: updating the concept of prebiotics. Nutr Res Rev 17:259–275

de Jesus Raposo MF, de Morais AM, de Morais RM (2016) Emergent sources of prebiotics: seaweeds and microalgae. Mar Drugs 14:27

Carlson JL, Erickson JM, Lloyd BB, Slavin JL (2018) Health effects and sources of prebiotic dietary fiber. Curr Dev Nutr 2:nyz005

Bindels LB, Segura Munoz RR, Gomes-Neto JC, Mutemberezi V, Martinez I, Salazar N, Cody EA, Quintero-Villegas MI, Kittana H, de Los Reyes-Gavilan CG, Schmaltz RJ, Muccioli GG, Walter J, Ramer-Tait AE (2017) Resistant starch can improve insulin sensitivity independently of the gut microbiota. Microbiome 5:12

Carlson JL, Erickson JM, Hess JM, Gould TJ, Slavin JL (2017) Prebiotic dietary fiber and gut health: comparing the in vitro fermentations of beta-glucan, inulin and xylooligosaccharide. Nutrients 9:1361

Day L, Gomez J, Oiseth SK, Gidley MJ, Williams BA (2012) Faster fermentation of cooked carrot cell clusters compared to cell wall fragments in vitro by porcine feces. J Agric Food Chem 60:3282–3290

Cook SI, Sellin JH (1998) Review article: short chain fatty acids in health and disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 12:499–507

Cummings JH, Pomare EW, Branch WJ, Naylor CP, Macfarlane GT (1987) Short chain fatty acids in human large intestine, portal, hepatic and venous blood. Gut 28:1221–1227

Wong JM, de Souza R, Kendall CW, Emam A, Jenkins DJ (2006) Colonic health: fermentation and short chain fatty acids. J Clin Gastroenterol 40:235–243

Hamer HM, Jonkers D, Venema K, Vanhoutvin S, Troost FJ, Brummer RJ (2008) Review article: the role of butyrate on colonic function. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 27:104–119

Magnusson MK, Isaksson S, Ohman L (2020) The anti-inflammatory immune regulation induced by butyrate is impaired in inflamed intestinal mucosa from patients with ulcerative colitis. Inflammation 43:507–517

Mathew OP, Ranganna K, Mathew J, Zhu M, Yousefipour Z, Selvam C, Milton SG (2019) Cellular effects of butyrate on vascular smooth muscle cells are mediated through disparate actions on dual targets, histone deacetylase (hdac) activity and pi3k/akt signaling network. Int J Mol Sci 20:2902

Morais JAV, Rodrigues MC, Ferreira FF, Ranjan K, Azevedo RB, Pocas-Fonseca MJ, Muehlmann LA (2020) Photodynamic therapy inhibits cell growth and enhances the histone deacetylase-mediated viability impairment in Cryptococcus spp. in vitro. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 29:101583

Uerlings J, Schroyen M, Bautil A, Courtin C, Richel A, Sureda EA, Bruggeman G, Tanghe S, Willems E, Bindelle J, Everaert N (2020) In vitro prebiotic potential of agricultural by-products on intestinal fermentation, gut barrier and inflammatory status of piglets. Br J Nutr 123:293–307

Canani RB, Costanzo MD, Leone L, Pedata M, Meli R, Calignano A (2011) Potential beneficial effects of butyrate in intestinal and extraintestinal diseases. World J Gastroenterol 17:1519–1528

Baxter NT, Schmidt AW, Venkataraman A, Kim KS, Waldron C, Schmidt TM (2019) Dynamics of human gut microbiota and short-chain fatty acids in response to dietary interventions with three fermentable fibers. MBio 10:e02566-02518

Guttman JA, Finlay BB (2009) Tight junctions as targets of infectious agents. Biochim Biophys Acta 1788:832–841

Louis P, Flint HJ (2017) Formation of propionate and butyrate by the human colonic microbiota. Environ Microbiol 19:29–41

Kaczmarek JL, Musaad SM, Holscher HD (2017) Time of day and eating behaviors are associated with the composition and function of the human gastrointestinal microbiota. Am J Clin Nutr 106:1220–1231

Karl JP, Hatch AM, Arcidiacono SM, Pearce SC, Pantoja-Feliciano IG, Doherty LA, Soares JW (2018) Effects of psychological, environmental and physical stressors on the gut microbiota. Front Microbiol 9:2013

Guzman JR, Conlin VS, Jobin C (2013) Diet, microbiome, and the intestinal epithelium: an essential triumvirate? Biomed Res Int 2013:425146

Carlson JL, Erickson JM, Hess JM, Gould TJ, Slavin JL (2018) Potential of butyrate to influence food intake in mice and men. Gut 67:1203–1204

Whelan K, Schneider SM (2011) Mechanisms, prevention, and management of diarrhea in enteral nutrition. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 27:152–159

O’Keefe SJ, Ou J, Delany JP, Curry S, Zoetendal E, Gaskins HR, Gunn S (2011) Effect of fiber supplementation on the microbiota in critically ill patients. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2:138–145

Sunkara LT, Achanta M, Schreiber NB, Bommineni YR, Dai G, Jiang W, Lamont S, Lillehoj HS, Beker A, Teeter RG (2011) Butyrate enhances disease resistance of chickens by inducing antimicrobial host defense peptide gene expression. PLoS ONE 6:e27225

Yan H, Ajuwon KM (2017) Butyrate modifies intestinal barrier function in ipec-j2 cells through a selective upregulation of tight junction proteins and activation of the akt signaling pathway. PLoS ONE 12:e0179586

Zheng L, Kelly CJ, Battista KD, Schaefer R, Lanis JM, Alexeev EE, Wang RX, Onyiah JC, Kominsky DJ, Colgan SP (2017) Microbial-derived butyrate promotes epithelial barrier function through il-10 receptor-dependent repression of claudin-2. J Immunol 199:2976–2984

Commins S, Steinke JW, Borish L (2008) The extended il-10 superfamily: Il-10, il-19, il-20, il-22, il-24, il-26, il-28, and il-29. J Allergy Clin Immunol 121:1108–1111

El Kasmi KC, Holst J, Coffre M, Mielke L, de Pauw A, Lhocine N, Smith AM, Rutschman R, Kaushal D, Shen Y, Suda T, Donnelly RP, Myers MG Jr, Alexander W, Vignali DA, Watowich SS, Ernst M, Hilton DJ, Murray PJ (2006) General nature of the stat3-activated anti-inflammatory response. J Immunol 177:7880–7888

Riley JK, Takeda K, Akira S, Schreiber RD (1999) Interleukin-10 receptor signaling through the jak-stat pathway. Requirement for two distinct receptor-derived signals for anti-inflammatory action. J Biol Chem 274:16513–16521

Hammami R, Fernandez B, Lacroix C, Fliss I (2013) Anti-infective properties of bacteriocins: an update. Cell Mol Life Sci 70:2947–2967

Mogensen TH (2009) Pathogen recognition and inflammatory signaling in innate immune defenses. Clin Microbiol Rev 22:240–273

Mazzurana L, Rao A, Van Acker A, Mjösberg J (2018) The roles for innate lymphoid cells in the human immune system. Semin Immunopathol 40:407–419

Blander JM (2016) Death in the intestinal epithelium-basic biology and implications for inflammatory bowel disease. FEBS J 283:2720–2730

van der Beek CM, Dejong CHC, Troost FJ, Masclee AAM, Lenaerts K (2017) Role of short-chain fatty acids in colonic inflammation, carcinogenesis, and mucosal protection and healing. Nutr Rev 75:286–305

Sun M, Wu W, Chen L, Yang W, Huang X, Ma C, Chen F, Xiao Y, Zhao Y, Ma C, Yao S, Carpio VH, Dann SM, Zhao Q, Liu Z, Cong Y (2018) Microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids promote th1 cell il-10 production to maintain intestinal homeostasis. Nat Commun 9:3555

Liss MA, White JR, Goros M, Gelfond J, Leach R, Johnson-Pais T, Lai Z, Rourke E, Basler J, Ankerst D, Shah DP (2018) Metabolic biosynthesis pathways identified from fecal microbiome associated with prostate cancer. Eur Urol 74:575–582

Segain JP, Raingeard D, de la Bletiere A, Bourreille VL, Gervois N, Rosales C, Ferrier L, Bonnet C, Blottiere HM, Galmiche JP (2000) Butyrate inhibits inflammatory responses through nfkappab inhibition: implications for Crohn’s disease. Gut 47:397–403

Kovarik JJ, Tillinger W, Hofer J, Holzl MA, Heinzl H, Saemann MD, Zlabinger GJ (2011) Impaired anti-inflammatory efficacy of n-butyrate in patients with ibd. Eur J Clin Investig 41:291–298

Vinolo MA, Rodrigues HG, Nachbar RT, Curi R (2011) Regulation of inflammation by short chain fatty acids. Nutrients 3:858–876

Fellermann K, Stange DE, Schaeffeler E, Schmalzl H, Wehkamp J, Bevins CL, Reinisch W, Teml A, Schwab M, Lichter P, Radlwimmer B, Stange EF (2006) A chromosome 8 gene-cluster polymorphism with low human beta-defensin 2 gene copy number predisposes to Crohn disease of the colon. Am J Hum Genet 79:439–448

Hamer HM, Jonkers DM, Vanhoutvin SA, Troost FJ, Rijkers G, de Bruine A, Bast A, Venema K, Brummer RJ (2010) Effect of butyrate enemas on inflammation and antioxidant status in the colonic mucosa of patients with ulcerative colitis in remission. Clin Nutr 29:738–744

Komiyama Y, Andoh A, Fujiwara D, Ohmae H, Araki Y, Fujiyama Y, Mitsuyama K, Kanauchi O (2011) New prebiotics from rice bran ameliorate inflammation in murine colitis models through the modulation of intestinal homeostasis and the mucosal immune system. Scand J Gastroenterol 46:40–52

Saura-Calixto F, Serrano J, Goñi I (2007) Intake and bioaccessibility of total polyphenols in a whole diet. Food Chem 101:492–501

Hung LM, Chen JK, Huang SS, Lee RS, Su MJ (2000) Cardioprotective effect of resveratrol, a natural antioxidant derived from grapes. Cardiovasc Res 47:549–555

Cassidy A (2018) Berry anthocyanin intake and cardiovascular health. Mol Aspects Med 61:76–82

Kazuhiko Uchiyama YN, Hasegawa G, Nakamura N, Takahashi J, Yoshikawa T (2013) Astaxanthin protects β-cells against glucose toxicity in diabetic db/db mice. Redox Rep 7:290–293

Gu J, Thomas-Ahner JM, Riedl KM, Bailey MT, Vodovotz Y, Schwartz SJ, Clinton SK (2019) Dietary black raspberries impact the colonic microbiome and phytochemical metabolites in mice. Mol Nutr Food Res 63:e1800636

Wankhade UD, Zhong Y, Lazarenko OP, Chintapalli SV, Piccolo BD, Chen JR, Shankar K (2019) Sex-specific changes in gut microbiome composition following blueberry consumption in c57bl/6j mice. Nutrients 11:313

Gyawali R, Ibrahim SA (2012) Impact of plant derivatives on the growth of foodborne pathogens and the functionality of probiotics. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 95:29–45

Brown DG, Borresen EC, Brown RJ, Ryan EP (2017) Heat-stabilised rice bran consumption by colorectal cancer survivors modulates stool metabolite profiles and metabolic networks: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Nutr 117:1244–1256

Saiprasad G, Chitra P, Manikandan R, Sudhandiran G (2013) Hesperidin alleviates oxidative stress and downregulates the expressions of proliferative and inflammatory markers in azoxymethane-induced experimental colon carcinogenesis in mice. Inflamm Res 62:425–440

Cheng L, Chen Y, Zhang X, Zheng X, Cao J, Wu Z, Qin W, Cheng K (2019) A metagenomic analysis of the modulatory effect of Cyclocarya paliurus flavonoids on the intestinal microbiome in a high-fat diet-induced obesity mouse model. J Sci Food Agric 99:3967–3975

Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Nilsson A, Akrami R, Lee YS, De Vadder F, Arora T, Hallen A, Martens E, Bjorck I, Backhed F (2015) Dietary fiber-induced improvement in glucose metabolism is associated with increased abundance of prevotella. Cell Metab 22:971–982

Vargas-Bello-Perez E, Cancino-Padilla N, Romero J, Garnsworthy PC (2016) Quantitative analysis of ruminal bacterial populations involved in lipid metabolism in dairy cows fed different vegetable oils. Animal 10:1821–1828

Petersen C, Wankhade UD, Bharat D, Wong K, Mueller JE, Chintapalli SV, Piccolo BD, Jalili T, Jia Z, Symons JD, Shankar K, Anandh Babu PV (2019) Dietary supplementation with strawberry induces marked changes in the composition and functional potential of the gut microbiome in diabetic mice. J Nutr Biochem 66:63–69

Si Tan JAC-M, Matthews VB, Koch H, O’Gara F, Croft KD, Ward NC (2018) Isoquercetin and inulin synergistically modulate the gut microbiome to prevent development of the metabolic syndrome in mice fed a high fat diet. Sci Rep 8:10100

Djuric Z, Bassis CM, Plegue MA, Ren J, Chan R, Sidahmed E, Turgeon DK, Ruffin MT IV, Kato I, Sen A (2018) Colonic mucosal bacteria are associated with inter-individual variability in serum carotenoid concentrations. J Acad Nutr Diet 118:606-616.e603

Ramos AFO, Terry SA, Holman DB, Breves G, Pereira LGR, Silva AGM, Chaves AV (2018) Tucuma oil shifted ruminal fermentation, reducing methane production and altering the microbiome but decreased substrate digestibility within a rusitec fed a mixed hay—concentrate diet. Front Microbiol 9:1647

Lin T, Zirpoli GR, McCann SE, Moysich KB, Ambrosone CB, Tang L (2017) Trends in cruciferous vegetable consumption and associations with breast cancer risk: a case-control study. Curr Dev Nutr 1:e000448

Kim JK, Strapazzon N, Gallaher CM, Stoll DR, Thomas W, Gallaher DD, Trudo SP (2017) Comparison of short- and long-term exposure effects of cruciferous and apiaceous vegetables on carcinogen metabolizing enzymes in Wistar rats. Food Chem Toxicol 108:194–202

Veeranki OL, Bhattacharya A, Tang L, Marshall JR, Zhang Y (2015) Cruciferous vegetables, isothiocyanates, and prevention of bladder cancer. Curr Pharmacol Rep 1:272–282

Kaczmarek JL, Liu X, Charron CS, Novotny JA, Jeffery EH, Seifried HE, Ross SA, Miller MJ, Swanson KS, Holscher HD (2019) Broccoli consumption affects the human gastrointestinal microbiota. J Nutr Biochem 63:27–34

Angelino D, Dosz EB, Sun J, Hoeflinger JL, Van Tassell ML, Chen P, Harnly JM, Miller MJ, Jeffery EH (2015) Myrosinase-dependent and -independent formation and control of isothiocyanate products of glucosinolate hydrolysis. Front Plant Sci 6:831

Bianchini F, Vainio H (2001) Allium vegetables and organosulfur compounds: do they help prevent cancer? Environ Health Perspect 109:893–902

Ried K, Travica N, Sali A (2018) The effect of kyolic aged garlic extract on gut microbiota, inflammation, and cardiovascular markers in hypertensives: the gargic trial. Front Nutr 5:122

Mohammed A, Guda C (2015) Application of a hierarchical enzyme classification method reveals the role of gut microbiome in human metabolism. BMC Genomics 16(Suppl 7):S16

Pascale A, Marchesi N, Marelli C, Coppola A, Luzi L, Govoni S, Giustina A, Gazzaruso C (2018) Microbiota and metabolic diseases. Endocrine 61:357–371

Nagy-Szakal D, Ross MC, Dowd SE, Mir SA, Schaible TD, Petrosino JF, Kellermayer R (2012) Maternal micronutrients can modify colonic mucosal microbiota maturation in murine offspring. Gut Microbes 3:426–433

Dicks LMT, Geldenhuys J, Mikkelsen LS, Brandsborg E, Marcotte H (2018) Our gut microbiota: a long walk to homeostasis. Benef Microbes 9:3–20

Ryan PM, Ross RP, Fitzgerald GF, Caplice NM, Stanton C (2015) Sugar-coated: exopolysaccharide producing lactic acid bacteria for food and human health applications. Food Funct 6:679–693