Abstract

Background

Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) programs have gained traction across US hospitals in the past two decades. Initially implemented for elective colorectal surgical procedures, ERAS has expanded to a variety of surgical service lines. There is little information regarding the extent to which various surgical service lines use ERAS.

Methods

A survey was performed to describe the prevalence of ERAS programs across surgical service lines in the USA. The survey had questions regarding the number of ERAS programs, operating rooms (ORs) and presence of anesthesia and/or surgery residency program at an institution. The survey was administered electronically to members of the American Society for Enhanced Recovery (ASER) and manually to participants at the 2018 Perioperative Quality and Enhanced Recovery Conference in San Francisco, CA.

Results

Responses were received from 88 unique institutions. The most commonly reported surgical service lines were colorectal (87%), gynecology (51%), orthopedic (49%), surgical oncology (39%), and urology (35%). A significant positive association was observed between the number of ORs and the number ERAS programs (Spearman’s Rho 0.5, p<0.0001). Furthermore, institutions that reported an anesthesia and/or surgery residency program had more ERAS programs (mean 5.0 ± 3.2) compared to those that did not (mean 2.0 ± 2.0) (Wilcoxon rank sum p< 0.001).

Conclusions

ERAS has expanded to a large extent outside of the colorectal surgery service line with increases notable in orthopedic surgery, obstetric/gynecology, surgical oncology, and urology procedures. Institutions with a higher number of ORs and the presence of an anesthesia and/or surgery residency program are associated with an increased number of ERAS programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) programs are evidence-based, multidisciplinary, surgical care pathways developed to expedite recovery and improve patient outcomes after elective surgery (Desiderdio et al. 2018; McConnell et al. 2018; Brown et al. 2018; Ban et al. 2019). ERAS, comprised of several specific, evidence-based protocols, allows for the standardization of surgical patient care preoperatively, intraoperatively, and postoperatively. Their use within the colorectal service line has been well-studied and, as a result, ERAS programs have expanded into additional surgical specialties (e.g., thoracic, cardiac, gynecology, and orthopedic). Yet, little is known about the prevalence of ERAS among various surgical services in the United States (US).

Therefore, we conducted a nationwide survey to characterize the prevalence of ERAS programs across different surgical service lines. By identifying the types of elective surgical patients enrolled in an ERAS pathway and the types of institutions implementing ERAS pathways, we aim to inform the ERAS community on the extent to which ERAS programs are used across the USA and to encourage more research into its use across various surgical service lines.

Methods

Data collection

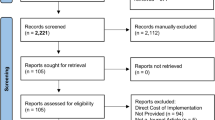

Institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained from Stony Brook University Medical Center IRB. The 9-question survey asked about the types of ERAS pathways, the number of operating rooms (ORs), and the presence of an anesthesia and/or surgery residency program at the respondent’s main hospital. The survey was designed, tested, and distributed electronically using the Qualtrics® (Provo, UT) online software to members of the American Society for Enhanced Recovery (ASER) between September and November 2018. The survey was also circulated to participants at the October 2018 Perioperative Quality and Enhanced Recovery Conference in San Francisco, CA.

Statistical analysis

Analysis was performed at the institutional level. To not over represent, i.e., double-count, institutions in the study, only the first completed survey was included for analysis from each institution. This response was selected first by completion rate, then by time/date submitted. If completion rates for the surveys were both 100% (fully completed survey), the first survey response received was used to represent the institution. Duplicate responses from institutions, surveys from unknown institutions, and non-US site responses were excluded from the analysis. Associations between the number of ERAS programs, the number of ORs, and the presence or absence of an anesthesia and/or surgery residency program, which served as surrogates for hospital size and academic status, were examined using Spearman’s rank and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Survey data related to carbohydrate beverage use will be published in a separate manuscript.

Results

Overall, 148 completed surveys were received, representing 88 unique hospitals. Respondents identified themselves as anesthesiologist (44.3%), ERAS coordinator (19.3%), surgeon (14.8%), nurse (10.2%), certified registered nurse anesthetist (3.4%), other (3.4%), nurse practitioner (2.3%), and dietitian (2.3%).

The majority of hospitals reported having an adult colorectal ERAS program (88.6%), followed by gynecology (51.1%), orthopedic (48.9%), surgical oncology (38.6%), and urology (35.2%). The least reported programs were thoracic (15.9%), ear-nose-throat [ENT] (14.8%), vascular (11.4%), cardiac (9.1%), and craniotomy (1.1%). Of the 88 hospitals, 4.6% reported not having any ERAS program. In total, there were fourteen programs reported, including “other,” as noted in Table 1.

Associations between the number of ERAS programs and the number of ORs and the number of ERAS programs and the presence/absence of an anesthesia or surgery residency program are described in Table 2. There was a 3-fold difference in the average number of ERAS programs by number of ORs between the smallest and largest categories, 2.2 ± 1.8 (1–10 ORs) compared to 6.4 ± 3.6 (>40 ORs). There was a significant positive association between the number of ORs and the number of ERAS programs (Spearman’s Rho 0.5, p<0.0001). Moreover, institutions that reported an anesthesia and/or surgery residency program had more ERAS programs (mean ± SD, 5.0 ± 3.2) compared to those that did not (mean ± SD, 2.0 ± 2.0, Wilcoxon rank sum < 0.001). Sensitivity analyses confirmed that responses were similar for electronically and manually administered surveys.

Discussion

ERAS elements span the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative care phases. Standardizing these components has had a positive impact on the overall quality of recovery (e.g., decreased surgical stress, length of stay, and reduced complications) (Ban et al. 2019).

In accordance with anecdotal reports, our survey shows within institutions that are likely to implement ERAS pathways, many enroll colorectal patients. Within these institutions however, our survey results suggest that ERAS has expanded, and pathways are being applied to a wide variety of other surgical services lines. As such, the ERAS® Society has promulgated evidence-based recommendations for many surgical service lines to guide perioperative patient care and improve healthcare delivery and outcomes.

We observed that institutions that are larger and/or have an anesthesia or surgery residency program are more likely to have more ERAS programs. We did not assess the reason(s) for this, but can speculate that larger institutions are more likely to have resources that can be devoted to expansion of ERAS and other quality improvement efforts. Regardless of size, encouraging sustainable ERAS expansion requires institutional commitment and support to embed ERAS as a standard model of care across multiple therapeutic areas. Once a hospital expands ERAS into multiple surgical procedures, it becomes impractical to use manual data capture. Therefore, IT resources are needed to allow for automated data capture and analysis including audit of compliance with bundle elements in order to optimize outcomes and patient satisfaction.

Our study has several potential limitations. The goal was not to assess the rate of ERAS expansion within the USA or the specific elements in the different pathways, e.g., goal-directed therapy; therefore, we cannot comment on how rapidly ERAS programs are being developed and implemented nor which ERAS elements are consistently used across different surgical service lines. Though our survey was not piloted prior to distribution, it was internally tested. It was administered electronically first to ASER members and then in-person (manually) to conference attendees, possibly leading to inconsistencies in responses. Yet, a sensitivity analysis showed similar results for electronic and manual survey responses. This is not surprising as we would not expect these results to markedly differ based on how the survey was delivered. Additionally, these results may be more generalizable to clinicians who are interested in enhanced recovery, as they are more likely to have attended the ASER meeting or be an ASER member and thus be approached and willing to complete the survey.

Conclusion

In summary, our study found that ERAS is being implemented in many different types of elective surgery. Additionally, centers with a higher number of ORs have a larger number of ERAS programs. Additional studies are needed to address the growth rate of ERAS programs within the USA, the shared elements between different ERAS pathways, and sustainable ways to support ERAS expansion across varied institutional settings.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used are not available.

Abbreviations

- ASER:

-

American Society for Enhanced Recovery

- ENT:

-

Ear, nose, throat

- ERAS:

-

Enhanced Recovery After Surgery

- IRB:

-

Institutional Review Board

- OR:

-

Operating room

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

References

Ban KA, Berian JR, Ko CY. Does implementation of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols in colorectal surgery improve patient outcomes? Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2019;32(2):109–13. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1676475.

Brown JK, Singh K, Dumitru R, Chan E, Kim MP. The benefits of enhanced recovery after surgery programs and their application in cardiothoracic surgery. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2018;14(2):77–88. https://doi.org/10.14797/mdcj-14-2-77.

Desiderdio J, Stewart CL, Sun V, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery for gastric cancer patients improves clinical outcomes at a US cancer center. J Gastric Cancer. 2018;18(3):230–41. https://doi.org/10.5230/jgc.2018.18.e24.

McConnell G, Woltz P, Bradford WT, Ledford JE, Williams JB. Enhanced recovery after cardiac surgery program to improve patient outcomes. Nursing. 2018;48(11):24–31. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NURSE.0000546453.18005.3f.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Department of Anesthesiology, Stony Brook University Medical Center, USA, and the American Society for Enhanced Recovery for their support in the conduct of this survey.

Funding

This work was supported by internal resources from Stony Brook University Medical Center, Department of Anesthesiology. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SS contributed to the design, execution, drafting, and revision of the work. AL contributed to the acquisition of data, drafting, and revision of the work. JR contributed to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data and revision of the work. JT contributed to the drafting and revision of the work. TG contributed to the drafting and revision of the work. EBG contributed to the design, execution, drafting, and revision of the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research study was approved by the Stony Brook Institutional Review Board, reference number 1314361-1.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

SS, AL, JR, TG, and EBG have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, S.M., Liverpool, A., Romeiser, J.L. et al. Types of surgical patients enrolled in enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programs in the USA. Perioper Med 10, 12 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13741-021-00185-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13741-021-00185-5