Abstract

Background

Current theories on biodiversity-carbon sequestration relationship describe biodiversity as an important factor influencing carbon storage, either through complementarity effect or by mass ratio effect. So far, the expected form of biodiversity-carbon relationships in tropical ecosystems has not been known with certainty. Therefore, we explored the relationship between aboveground carbon stock and different biodiversity measurement indices (i.e., species richness, species diversity, species evenness, and functional diversity) in different land cover types of Eastern Ethiopia. A total of 48 plots were established using stratified random sampling. Vegetation parameters such as diameter at breast height, diameter at stump height, tree height, and species type were recorded.

Results

We found that the average aboveground carbon stock of the study area is 147.6 ± 17.2 t ha−1 (mean, SE) across land cover types. Species richness, Shannon index, and functional diversity together explained 73.5%, 61.4%, 58.9%, and 52.0% of the variation in aboveground carbon storage in woodland, riparian forest, bushland, and farmland, respectively. Functional diversity was a significant predictor explaining the total aboveground carbon stocks (26.7%) across the land cover types. The effects of biodiversity on aboveground carbon storage were mediated by functional diversity and presence and dominance of species. This shows that both the selection effects and the niche complementarity are important for carbon storage. However, the impact of functional diversity effects (niche complementarity) was higher than that of functional dominance effects (selection effects).

Conclusions

Implementation of protected area-based ecosystem conservation practices in the country seems feasible to mitigate climate change and Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) programme should emphasize on biodiversity conservation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global biodiversity is increasingly threatened by human domination of the natural ecosystem and its concomitant impacts that accelerate rates of biodiversity loss and homogenization through invasion (Sala et al. 2000). Loss of biodiversity might cause a significant change in CO2 exchanges between the land and the atmosphere (Thomas 2013). The change raises fundamental questions such as “will biodiversity loss and variation alter basic ecosystem processes of carbon storage?” To address such questions, in the past 30 years, increasingly considerable attention has been given to in the determination of relationships between biodiversity and ecosystem functions. Although loss of biodiversity is relatively well studied, quantitative assessments of the association between biodiversity and its potential ecosystem function, particularly its role in carbon (C) storage, have not been adequately addressed (Thomas 2013; Harpole et al. 2016).

In terrestrial ecosystems, biodiversity influences both the magnitude (Reich et al. 2001; Tilman et al. 2014) and variability (Bai et al. 2004) of aboveground biomass. Aboveground biomass can significantly determine carbon storage potential of the ecosystem, which plays a significant role in balancing the global carbon budget (Mensah et al. 2016; Forrester et al. 2018). Current theories on biodiversity-carbon sequestration relationship describe biodiversity as an important factor influencing carbon storage, weather, and forest diversity effects which are driven by niche partitioning and facilitation (i.e. the complementarity effect) or by the selection of highly productive species such as the selection effect (i.e., the mass ratio effect) (Cardinale et al. 2012; Madrigal-González et al. 2016; Van Der Sande et al. 2017). The niche complementarity hypothesis states that diverse characteristics of species have a higher divergence of functional traits and can thus help to utilize resources better (Cardinale et al. 2012; Tilman et al. 2014; Yuan et al. 2018). The mass ratio hypothesis states that diversity can increase productivity through selection effects (Loreau and Hector 2001; Oram et al. 2017; Van Der Sande et al. 2017). Positive diversity-productivity relationships have been also found in low diversity mid-latitude (Forrester et al. 2018; Vanhellemont et al. 2018), due to a large canopy packing through complimentary canopy in higher diversity ecosystems (Jucker et al. 2016). Yet, the expected forms of biodiversity-carbon relationships in tropical ecosystems are not fully understood (Cardinale et al. 2012; Liang et al. 2016; Forrester et al. 2018). Thus, a better understanding of how biodiversity affects carbon storage would help direct preservation, conservation, and restoration plans for exploited ecosystems.

Most studies that examined diversity-carbon storage relationships focused principally on species richness as a measure of biodiversity. In fact, biodiversity can be determined in different ways, as the number of species (species richness), the distribution of individuals over species (species evenness), or a combination of richness and evenness, as represented by Shannon index (Stirling and Wilsey 2001). Results of several studies led to the argument that evenness, Shannon index and species richness are different independent indices (Mason et al. 2005; Wilsey and Stirling 2007; MacDonald et al. 2017), and the recommendation that they be treated separately (Stirling and Wilsey 2001; Zhang et al. 2012a). Thus, evaluating the effects of different diversity metrics on carbon stock potential has been demonstrated to be rare (Zhang et al. 2012b; Forrester et al. 2018). The different metrics of diversity may have different predictive powers in different land cover types for predicting carbon storage potential. In this study, we tested the effect of different diversity metrics on aboveground carbon stocks.

Ethiopia is recognized as a hotspot for biodiversity but is suffering from rapid and extensive loss of biodiversity (Myers et al. 2000; Goren et al. 2012; Di Marco et al. 2014). The demand of forest products is quite pronounced as more than 85% of the people living in rural areas that mostly rely on biodiversity for their basic needs such as cattle feed, fuelwood, food, and shelter. In spite of the increasing demand, Ethiopia has been able to maintain a considerable area of land for biodiversity conservation during the last decade. The rate of afforestation in the country is considered to be one of the highest among sub-Saharan countries and has played a role in maintaining biodiversity particularly forest cover and productivity. Despite efforts being exerted to conserve the increasing biodiversity, our knowledge on the role of biodiversity as dynamic C-pools in biogeochemical cycles and the mechanisms underlying the effects of diversity on carbon stock is largely unknown. This would pose challenges to policy development aimed at promoting, managing, or protecting biodiversity to safeguard the atmospheric environment from Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions, in addition to providing local people with reasonable means of livelihood. Therefore, it is necessary to understand the role of biodiversity in storing carbon, which is fundamental in quantifying its contribution to climate change mitigation since the quantified amount of carbon indicates the amount of carbon that can be offset (Ditt et al. 2010; Jabareen 2013; Felton and Gustafsson 2016). However, carbon stocks and woody species diversity in different land use types have not been assessed in Babile Elephant Sanctuary. Moreover, it is not clear how different measures of biodiversity are correlated with aboveground carbon stock. Do land use types show variations in aboveground carbon stock? What relationships do exist between different biodiversity measurement indices and aboveground carbon stock under different land use types? Here, we explored the relationships between aboveground carbon stock and different biodiversity measurement indices (i.e., species richness, species diversity, species evenness, and functional diversity) in the different land cover types of Eastern Ethiopia.

Materials and methods

Study site

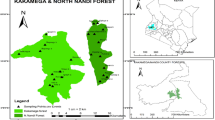

Babile Elephant Sanctuary (BES) is situated in the Somali-Masaai centre of endemism in Ethiopia. The sanctuary, which is 6892 km2 in size, was established in 1970 to protect the only viable elephant population in the Horn of Africa. The sanctuary is located 560 km to the east of Addis Ababa (capital city of Ethiopia). Its geographical position is within latitudes of 08° 22′ 30′′—09° 00′ 30′′ N and longitudes of 42° 01′ 10′′–43° 05′ 50′′ E (Fig. 1) and has an elevation ranging between 850 and 1785 m above sea level. Topographically, it is predominantly characterized by flat to gentle slopes, comprising about 84% of the total sanctuary area while the remaining 16% consists of complex valleys and deep gorges. Four main drainage river valleys (Fafem, Dakata, Erer and Gobele) rise from Garamuleta-Gursum highlands, and these extend southwards through the sanctuary to join the Wabi Shebelle River Basin. Wide ranges of wildlife species inhabiting the sanctuary include the African elephant (Loxodonta africana), black-maned lion (Panthera leo), leopard (P. pardus), and Hamadryas baboon (Papio hamadryads). The sanctuary is also shelter for a range of antelopes, lesser and greater kudus, leopards, spotted hyenas, wild pigs, warthog, and a variety of reptiles and birds.

Study area and site selection

The study sites were selected using stratified purposive sampling. Four different land cover categories (i.e., treatments) were identified, namely, farmland, riparian forest, woodland, and bushland (Table 1). The description of the land cover classes was based on the standard classes defined by the US Geological Survey (Mohan et al. 2011), and land use land cover study conducted in the study area (Sintayehu and Kassaw 2019).

Sampling and plot establishment

A reconnaissance survey was carried out in order to have an impression of the site conditions and determine samples of farmland, riparian forest, woodland, and bushland cover types. Plant species diversity, vegetation structure, and carbon stock potential of the study area in different land cover types were studied by using a stratified sampling method. First, the study area was stratified according to land cover type. In each land cover type, a total of four transect lines of 1000 m each, which were 300 m apart, were established systematically. In each transect, at an interval of 200 m, main plots of 10 m × 10 m for trees, 4 m × 4 m for shrub, and 1 m × 1 m for herbaceous land were established. Aboveground carbon was assessed for each nested sub-plot (Henry et al. 2011; Dabasso et al. 2014). The assessments were done for two consecutive wet and dry seasons from 2015 to 2017.

Data collection

Aboveground woody carbon assessment

In the established sub-plots (n = 20 per land cover type per season), the woody plant diameters were measured using a diameter tape at breast height (i.e., 1.3 m above ground) (Ditt et al. 2010). Diameter measurement for trees and lianas was taken at breast height (1.3 m) using a calliper. For tree species that branched at breast height, the diameters were measured separately above the swelling, and the average measurements were recorded. For tree species that forked below 1.3 m, individual stem diameters were separately measured and treated as two trees (Abed and Stephens 2003). Tree species were recorded for all trees within the plots using scientific and local names. For trees that were difficult to identify, voucher specimens were brought to the Herbarium of Haramaya University for identification where the voucher specimens of plant species were deposited.

Aboveground herbaceous carbon assessment

Herbaceous materials within 1 m2 were then clipped at 1 cm stubble height. The clipped materials, together with litters, were put in to paper bags, and their fresh weights were recorded. The aboveground materials of herbaceous plants were oven-dried at 80 °C for 48 h.

Data analysis

Four indices of plant diversity were calculated per plot, namely, species richness, species diversity, species evenness, and functional diversity. Species richness is the total number of species present within a plot in each land cover types. Functional diversity was calculated at the plot level, following the methods of Paquette and Messier (Paquette and Messier 2011).

Functional traits that are related to carbon storage were considered to assess functional diversity (Mensah et al. 2016). Carbon storage is strongly dependent on wood density, diameter of the plant, and maximum plant height. Thus, for functional diversity, we calculated the dispersion for wood density, maximum DBH, and maximum height based on the trait value of the species present at each plot (Mensah et al. 2016). Shannon diversity index (H’) was calculated for each plot, which has been used to estimate plant species diversity as:

where pi is the proportion of species i, and S is the number of species (Hill, 1973).

Pielou’s index was used to estimate plant species evenness (Hill 2007), which is most widely used in ecology (Zhang et al. 2012a):

where H′ represents the Shannon diversity index, and S is the total number of species observed. Biodiversity metrics were calculated using package vegan of R v3.2.0.

Aboveground carbon stocks

Aboveground carbon (AGC) stocks were calculated for all land cover type by summing the values for the nested plots along each land cover type, and dividing by the total sampled area, in ha.

Aboveground carbon assessment of woody species

The diameter at breast height (DBH) (1.3 m above the ground) of all the trees within 10 m × 10 m nested sub-plots and basal diameters (BD) of all shrubs within the 4 m × 4 m nested sub-plots was taken using a flexible measuring tape. Both DCH and BD were recorded, and carbon estimates within each plant were done using allometric equations as described by Henry et al. (2011) as follows:

Trees: Y = 0.1975 × (DBH^(1.1859))

Shrubs: Y = 0.1936 × (BD^(1.1654))

where Y is the fresh weight of trees/shrub biomass (kg).

The results of allometric equation provide fresh biomass estimates. In order to measure dry biomass, the results were multiplied by 60%, and the aboveground carbon content was taken as 50% of the dry biomass weight (Henry et al. 2011; Saatchi et al. 2011). Aboveground carbon estimates within nested sub-plots were converted to carbon in tons per hectare (1 ton = 1000 kg, 1 ha = 10,000 m2).

Aboveground carbon assessment of herbaceous species

Herbaceous carbon contents were calculated as 50% of oven-dried herbaceous biomass. The results were recorded in a prepared data sheet. Sample results were then converted into carbon tons per hectare (1 ton = 1,000,000 g) (Henry et al. 2011; Dabasso et al. 2014).

Pearson statistical tests were performed to test correlations between aboveground carbon stocks and biodiversity for different land cover types. We used ANOVA using R’s “car” package to test the effects of land cover types on total AGC stocks in different seasons. To estimate the variation explained by each biodiversity measurement indices, adjusted R2 (Bunker et al. 2005) was used. We performed these analyses using the vegan package in R. All analyses were carried out in R v3.2.2 (R Development Core Team, 2015).

Results

Vegetation structure and floristic composition

A total of 137 plant species were identified and measured over 48 plots of the survey area belonging to 85 genera and 41 families (Appendix in Table 5). The mean stand density was 419 ± 28 stems ha–1. The number of stands ranged from 24 to 2458 stems ha–1. The mean diameter was 1.27 ± 0.21 m, with the majority of trees being found within the smaller diameter classes (Table 2). The mean basal area was 14.34 ± 0.52 m2 ha–1, with a minimum of 10.48 and maximum of 18.8 m2 ha–1across the plots.

Diversity of plant species

Species richness in the study area was significantly different among land cover types (F = 4.65, P < 0.01), as woodland had higher species richness (n = 48; Table 2). Species diversity as measured by the Shannon index (H′) ranged from 2.62 to 0.78 (Table 2) and was found to be high in the woodland (H′ = 2.62) and riparian forest (H′ = 2.50), and low (H′ = 0.78) for farmland where the high and low H′ values were significantly different (P < 0.05). Species evenness was not significantly different between land cover types (F = 0.61, P = 0.55). The functional diversity ranged from 0.80 to 0.92 (Table 2).

Aboveground carbon stocks

The total aboveground carbon stock of the area in different land cover types ranged between 7.14 and 71.16 t ha−1 (Table 3). The total carbon stocks from the different land use types showed a statistically significant difference (P < 0.001) (Table 3). The largest aboveground C stocks were found for the riparian forest (71.16 ± 0.91 t ha−1), followed by woodland (43.09 ± 0.42 t ha−1), whereas the smallest aboveground C stocks were measured for the farmland (7.14 ± 0.38 t ha−1).

Relationship between diversity and aboveground carbon stocks

Species richness, Shannon index (H′), and functional diversity together explained 73.5, 61.4, 58.5, and 51.6% of the variations in the aboveground carbon storage in woodland, riparian forest, bushland, and farmland, respectively, and the contribution to carbon storage variation differed among the land cover types (Fig. 2).

Functional diversity explained most of the variations in the aboveground carbon storage on riparian forest (42.1%) and woodland (28.1%); more specifically, we found that the more DBH and Hmax of a plot, the greater the increase in carbon storage. Species diversity explained most of the tree carbon storage variation (22.1%) in farmland. Another important source of variation was the interaction between species diversity and functional diversity which explained 11% of the carbon storage variation in riparian forest, 6% in bushland, and 4% in woodland. The relationships between species richness and total aboveground carbon stock were significant for riparian forest enclosures (r = − 0.15, p < 0.05). The relationships between species diversity (Shannon) and total aboveground carbon stock were also significant for bushland (r = 0.39, p < 0.05) and farmland (r = 0.52, p < 0.05). Functional diversity showed significant relation with total carbon stock, for riparian forest (r = 0.81, p < 0.001), for woodland (r = 0.58, p < 0.01), and bushland (r = 0.45, p < 0.05) (Table 4).

Discussion

The results of the study revealed that the aboveground carbon stocks were positively correlated with biodiversity, which confirms the positive association commonly observed between diversity and biomass in different experimental studies (Cardinale et al. 2006, 2007, 2011; Duffy et al. 2007; Delgado-Baquerizo et al. 2016), as well as in recent in situ forestry studies (Wang et al. 2009; Saatchi et al. 2011; Finegan et al. 2015; Delgado-Baquerizo et al. 2016). Thus, the results support the positive biodiversity-ecosystem functioning hypothesis. This synergistic association suggests that conservation of biodiversity can lead to enhanced quantities of carbon stored in a given area.

The results of the aboveground carbon storage in natural ecosystems (riparian forest, woodland, and bushland) were mainly explained by functional diversity incorporating wood density, maximum diameter, and maximum height traits in natural habitat and carbon stocks. However, we found no association between carbon storage and species richness in the natural ecosystems. Similarly, reports by Zhang et al. (2012a) indicated that no significant relationship was found between aboveground carbon storage and species richness in naturally regenerating conifer stands in China. Species richness only mattered in agricultural land, where increasing the number of species also increased carbon storage. This association was expected because in agricultural land crops, there are planted according to different species functions, including provision of shade, control of wind erosion, and nutrient recycling ability (Richards et al. 2010). Lack of significant correlation between carbon storage and species richness in the natural ecosystems indicates that the ecosystems may have reached saturation in species richness, an effect that can be found in high species richness treatments in experimental grasslands (Cardinale et al. 2011). In those systems, < 15 species are needed to reach the highest values of plant productivity (Loreau and Hector 2001; Van Der Sande et al. 2017). Saturation between carbon storage and species number can differ among sites and is determined by the niche overlap among species (Cardinale et al. 2007).

The study shows a clear correlation between functional diversity and total carbon stock. The significant positive correlation between aboveground carbon stocks potential and a functional diversity consisting of wood density and maximum diameter traits might be due to complementarity effect, in which a diverse array of species has a greater divergence of functional traits and can thus better utilize limiting resources, thus increasing total ecosystem functioning, than a less diverse community. The complementarity effect is the increase in relative productivity among species in a mixture compared with the productivity of the species grown in monocultures due to positive interactions among species (i.e., facilitation and partitioning of resources) (e.g., Reich et al. 2001; Tilman et al. 2014). Positive diversity-productivity relationships have been found in low diversity mid-latitude forests, potentially due to increased canopy packing through complimentary canopy in higher diversity areas. Studies have showed that plant diversity enhances biomass production, with niche partitioning and positive interactions among species allowing diverse communities to utilize resources more effectively.

We chose wood density, maximum diameter at breast height (DBH), and maximum height as functional traits related to tree carbon storage (Baker et al. 2004; Jucker et al. 2016). Martinez-Garza (2013) showed that functional traits have been proposed as an improved way to understand forest dynamics in hyper diverse tropical forests because they are considered the redundancy in function of species. This function can cluster species based on their resource use. To link functional traits to a specific function, we need to select traits that are related to carbon storage function of the ecosystem. Wood density partly determines aboveground biomass (Day et al. 2018) and correlates with growth rates and tree mortality (Madrigal-González et al. 2016), a high wood density being associated with long-lived and slowly growing plant species. Similar with the results of previous studies, we found that both basal area and density of woody species are constituents of biomass estimates (Cruz et al. 2004; Jucker et al. 2016; Vanhellemont et al. 2018). These two structural characteristics of aboveground carbon stocks per unit area are themselves largely unrelated to species richness, indicating that diversity is not a correlate of the key structural factors that lead to high biomass in some tropical forest stands (Bunker et al. 2005; Jucker et al. 2016). Woody plant diameter inequality, which has been described as a mechanism associating carbon and biodiversity in boreal forests, was positively correlated to aboveground carbon stock but unrelated to species richness (Paquette and Messier 2011; Harpole et al. 2016). We recognize that our conclusions are based on correlative studies, and that further studies with experimental manipulation, including dominant species traits and interaction among functional traits, are required to thoroughly test this hypothesis. However, our results are a necessary first step towards understanding the role of biodiversity on aboveground carbon stock and identifying the underlying mechanisms.

Our study showed that the aboveground carbon stock potential of natural vegetation was higher than that of agricultural land. A study by Wang et al. (2009) found a 22% reduction in soil carbon stocks when uncultivated land was converted into agricultural land. Any human activities that might have serious impact on soils will, therefore, have major implications in declining carbon stocks in the cultivated land. Conversion of natural vegetation to agricultural land was known to decrease soil carbon stocks due to disturbance of the soil surface (Jiao et al. 2009; Finegan et al. 2015). It is, therefore, important to guard natural landscape from degradation that will eventually interfere with soil condition, thereby reducing the amount of carbon stock potential.

Conclusions

The findings of this study have demonstrated that it is not exclusively that the selection and the niche complementarily effects influence carbon stock. Rather, the results have revealed that the influences were significantly attributable to functional diversity. However, the results require to be substantiated and validated through further studies in similar ecosystems. Therefore, the results of our study support stronger complementary effects that might be due to complementary light-use efficiency of woody plant growth in the understory layer. The findings also instigate that conservation efforts focused on protected area-based biodiversity conservation with ecosystem networks that may benefit both functional biodiversity and ecosystem services linked to carbon storage, like climate change mitigation. In this study, we have estimated aboveground carbon stocks as a case study of tropical deciduous woodland ecosystems under diverse land cover change, taking into considerations spatial and temporal heterogeneity of the ecosystem. The variation in carbon storage with land cover types affirms the need to examine asymmetric variation of environmental resource in the measurement of ecosystem carbon stocks. The results have also revealed that, compared to the cultivated land, natural ecosystems stored substantial amounts of carbon. The results of this study might also lead to initiation of a large-scale study in the Ethiopia deciduous woodland ecosystems on aboveground carbon stocks stored in soils and vegetation to analyze the relationship between structural and functional biodiversity and ecosystem services linked to carbon storage for better planning of ecosystem conservation and management.

Availability of data and materials

The authors declare that all data and materials used in the publication will be available online.

Abbreviations

- BES:

-

Babile Elephant Sanctuary

- DBH:

-

Diameter at breast height

- BD:

-

Basal diameter

- AGC:

-

Aboveground carbon

References

Abed T., Stephens N.C. (2003) Calculating volumes for stands greater than three hectares. In Tree Measurement Manual for Farm Foresters. 2nd edn. Ed M. Parsons. Canberra: National Forest Inventory, Bureau of Rural Sciences, Commonwealth of Australia. 43–52.

Bai Y, Han X, Wu J, Chen Z, Li L (2004) Ecosystem stability and compensatory effects in the Inner Mongolia grassland. Nature 44:1992–1995

Baker TYR, Phillips OL, Malhi N, Almeida S, Arroyo L, Anthony Difiorek A et al (2004) Variation in wood density determines spatial patterns in Amazonian forest biomas. Glob Chang Biol 10:545–562

Bunker DE, Declerck F, Bradford JC, Colwell RK, Perfecto I, Phillips OL, Sankaran M, Naeem S (2005) Species loss and aboveground carbon storage in a tropical forest. Science 310:1029–1031

Cardinale BJ, Duffy JE, Gonzalez A, Hooper DU, Perrings C, Venail P et al (2012) Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature 486:59–67

Cardinale BJ, Matulich KL, Hooper DU, Byrnes JE, Duffy E et al (2011) The functional role of producer diversity in ecosystems. Am J Bot 98(3):572–592

Cardinale BJ, Srivastava DS, Duffy JE, Wright JP, Downing AL, Sankaran M et al (2006) Effects of biodiversity on the functioning of trophic groups and ecosystems. Nature 443:989–992

Cardinale BJ, Wright JP, Cadotte MW, Carroll IT, Hector A, Srivastava AS et al (2007) Impacts of plant diversity on biomass production increase through time because of species complementarity. PNAS 104:18123–18128

Cruz CD, Regazzi AJ, Carneiro AJ, Souza PC (2004) Modelos biométricos aplicados ao melhoramento genético. UFV, Viçosa

Dabasso BH, Taddese Z, Hoag D (2014) Carbon stocks in semi-arid pastoral ecosystems of northern Kenya. Pastoralism 4:5

Day M, Baldauf C, Rutishauser E, Sunderland TCH (2018) Relationships between tree species diversity and above-ground biomass in Central African rainforests: implications for REDD. Environ Conserv 41:64–72

Delgado-Baquerizo M, Giaramida L, Reich PB, Khachane AN, Hamonts K, Edwards C et al (2016) Lack of functional redundancy in the relationship between microbial diversity and ecosystem functioning. J Ecol 104:936–946

Di Marco M, Boitani L, Mallon D, Hoffmann M, Iacucci A, Meijaard E, Visconti P, Schipper J, Rondinini C (2014) A retrospective evaluation of the global decline of carnivores and ungulates. Conserv Biol 28:1109–1118

Ditt EH, Mourato S, Ghazoul J, Knight J (2010) Forest conversion and provision of ecosystem services in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Land Degrad Dev 21:591–603

Duffy JE, Cardinale BJ, France KE, McIntyre PB, Thébault E, Loreau M (2007) The functional role of biodiversity in ecosystems: incorporating trophic complexity. Ecol Let 10:522–538

Felton A, Gustafsson L (2016) How climate change adaptation and mitigation strategies can threaten or enhance the biodiversity of production forests: Insights from Sweden. Biol Conserv 194:11–20

Finegan B, Pena-Claros M, de Oliveira A, Ascarrunz N, Bret-Harte MS, Carreno-Rocabado G et al (2015) Does functional trait diversity predict above-ground biomass and productivity of tropical forests? Testing three alternative hypotheses. J Ecol 103:191–201

Forrester DI, Bauhus J, Cowie AL, Vanclay JK (2018) Mixed Species Plantations of Eucalyptus with Nitrogen-fixing Trees: A Review. Forest Ecology and Management 233:211–230

Goren LJ, Romaine S, Mittermeier RA, Walker-Painemilla K (2012) Co-occurrence of linguistic and biological diversity in biodiversity hotspots and high biodiversity wilderness areas. PNAS 109:8032–8037

Harpole WS, Sullivan LL, Lind EM, Firn J, Adler PB, Borer ET et al (2016) Addition of multiple limiting resources reduces grassland diversity. Nature 537:93–96

Henry M, Picard N, Trotta C, Manlay C, Valentini RJ, Bernoux R et al (2011) Estimating tree biomass of Sub-Saharan African Forests: a review of available allometric equations. Silva Fennica 45:477–569

Hill MO (1973) Diversity and evenness: a unifying notation and its consequences. Ecology 54:427–452

Hill MO (2007) Diversity and evenness: a unifying notation and its consequences. Ecology 54:427–432

Jabareen Y (2013) Planning the resilient city: Concepts and strategies for coping with climate change and environmental risk. Cities 31:220–229

Jiao J, Zhang Z, Bai W, Jia Y, Wang N (2009) Assessing the ecological success of restoration by afforestation on the Chinese Loess Plateau. Restor Ecol 20:240–249

Jucker T, Sanchez AC, Lindsell JA, Allen HD, Amable GS, Coomes DA (2016) Drivers of aboveground wood production in a lowland tropical forest of West Africa: teasing apart the roles of tree density, tree diversity, soil phosphorus, and historical logging. Ecol Evol 6:4004–4017

Liang J, Crowther TW, Picard N, Wiser S, Zhou M, Alberti G, Schulze ED et al (2016). Positive biodiversity-productivity relationship predominant in global forests. Science 354:aaf8957

Loreau M, Hector A (2001) Partitioning selection and complementarity in biodiversity experiments. Nature 412:72–76

MacDonald ZG, Nielsen SE, Acorn JH (2017) Negative relationships between species richness and evenness render common diversity indices inadequate for assessing long-term trends in butterfly diversity. Biodivers Conserv 26:617–629

Madrigal-González J, Ruiz-Benito P, Ratcliffe S, Calatayud J, Kandler G, Lehtonen A, Dahlgren J, Wirth C, Zavala MA (2016) Complementarity effects on tree growth are contingent on tree size and climatic conditions across Europe. Sci Rep 6:32233

Martinez-Garza C, Bongers F, Poorter L (2013) Are functional traits good predictors of species performance in restoration plantings in tropical abandoned pastures? Forest Ecol Manag 303:35–45.

Mason NWH, Mouillot D, Lee WG et al (2005) Functional richness, functional evenness and functional divergence: the primary components of functional diversity. Oikos 111:112–118

Mensah S, Veldtman R, Assogbadjo AE, Seifert T, Kakai RG (2016) Tree species diversity promotes aboveground carbon storage through functional diversity and functional dominance. Ecol Evol 6:7546–7557

Mohan M, Pathan SK, Narendrareddy K, Kandya A, Pandey S (2011) Dynamics of urbanization and its impact on land-use/land-cover: a case study of Megacity Delhi. J Environ Prot 2:1274–1283

Myers N, Mittermeier RA, Mittermeier CG, da Fonseca GAB, Kent J (2000) Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403:853–858

Oram NJ, Ravenek JM, Barry KE, Gessler A, Chen H, Weigelt A et al (2017) Below-ground complementarity effects in a grassland biodiversity experiment are related to deep-rooting species. J Ecol 106:265–277

Paquette A, Messier C (2011) The effect of biodiversity on tree productivity: from temperate to boreal forests. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 20:170–180

R Development Core Team (2015) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna

Reich PB, Knops J, Tilman D, Craine J, Ellsworth D, Tjoelke M et al (2001) Plant diversity enhances ecosystem responses to elevated CO2 and nitrogen deposition. Nature 410:809–812

Richards AE, Forrester DI, Bauhus J, Scherer-Lorenzen M (2010) The influence of mixed tree plantations on the nutrition of individual species: a review. Tree Physiol 30:1192–1208

Saatchi SS, Harris NL, Brown S, Lefskyd M, Mitcharde ETA, Salas W et al (2011) Benchmark map of forest carbon stocks in tropical regions across three continents. PNAS 108:9899–9904

Sala OE, Chapin FS, Armesto JJ, Berlow E, Bloomfield J, Dirzo R et al (2000) Global biodiversity scenarios for the year 2100. Science 287:1770–1774

Sintayehu WD, Kassaw M (2019) Impact of land cover changes on elephant conservation in Babile Elephant Sanctuary, Ethiopia. Biodiversity Int J 3:65–71

Stirling G, Wilsey B (2001) Empirical relationships between species richness, evenness, and proportional diversity. Am Nat 158:286–299

Thomas CD (2013) Local diversity stays about the same, regional diversity increases, and global diversity declines. PNAS 110:19187–19188

Tilman D, Isbell F, Cowles JM (2014) Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 45:471–493

Van Der Sande M, Poorter L, Kooistra L, Balvanera P (2017) Biodiversity in species, traits, and structure determines carbon stocks and uptake in tropical forests. Biotropica 49:593–603

Vanhellemont M, Bijlsma RJ, De Keersmaeker L, Vandekerkhovec K, Verheyen K (2018) Species and structural diversity affect growth of oak, but not pine, in uneven-aged mature forests. Basic Appl Ecol 27:41–50

Wang W, Lei X, Ma Z, Kneeshaw DD, Peng C (2009) Relationships between stand growth and structural diversity in spruce-dominated forests in New Brunswick, Canada. For Sci 57:506–515

Wilsey B, Stirling G (2007) Species richness and evenness respond in a different manner to propagule density in developing prairie microcosm communities. Plant Ecol 190:259–273

Yuan Z, Wang S, Ali A, Gazol A, Ruiz-Benito P, Wang X, Lin F, Ye J, Hao Z, Loreau M (2018) Aboveground carbon storage is driven by functional trait composition and stand structural attributes rather than biodiversity in temperate mixed forests recovering from disturbances. Ann For Sci 75:67

Zhang H, John R, Peng Z, Yuan J, Chu C, Du G, Zhou S (2012a) The relationship between species richness and evenness in plant communities along a successional gradient: a study from sub-alpine meadows of the Eastern Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, China. PLoS One 7:e49024

Zhang Y, Chen HYH, Reich PB (2012b) Forest productivity increases with evenness, species richness and trait variation: a global meta-analysis. J Ecol 100:742–749

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Haramaya University for funding this research.

Funding

This study was funded by Haramaya University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SWD, AB, and ND initiated the work, and writing and revising the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sintayehu, D.W., Belayneh, A. & Dechassa, N. Aboveground carbon stock is related to land cover and woody species diversity in tropical ecosystems of Eastern Ethiopia. Ecol Process 9, 37 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-020-00237-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-020-00237-6