Abstract

Background

In Ethiopia, child wasting has remained a public health problem for a decade’s, suggesting the need to further monitoring of the problem. Hence, this study aimed at assessing the prevalence of wasting and associated factors among children aged 6–59 months at Dabat District, northwest Ethiopia.

Methods

A Community based cross-sectional study was undertaken from May to June, 2015, in Dabat District, northwest Ethiopia. A total of 1184 children aged under five years and their mothers/caretakers were included in the study. An interviewer-administered, pre-tested, and structured questionnaire was used to collect data. Standardized anthropometric body measurements were employed to assess the height and weight of the participants. Anthropometric body measurements were analyzed by the WHO Anthro Plus software version 1.0.4. Wasting was defined as having a weight–for–height of Z–score lower than two standard deviations (WHZ < −2 SD) compared to the WHO reference population of the same age and sex group. In the binary logistic regression, both bivariate and multivariate analyses were done to list out factors associated with wasting. All variables with P–values of < 0.2 in the bivariate analysis were earmarked for the multivariate analysis. Both Crude Odds Ratio (COR) and Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) at 95% Confidence Interval (CI) were computed to determine the strength of association. In the multivariate analysis, variables at P–values of < 0.05 were identified as determinants of wasting.

Results

The overall prevalence of wasting was 18.2%; 10.3% and 7.9% of the children were moderately and severely wasted, respectively. Poor dietary diversity [AOR = 2.08, 95% CI: 1.53, 4.46], late initiation of breastfeeding [AOR = 1.43, 95% CI: 1.04, 1.95], no postnatal vitamin-A supplementation [AOR = 1.55, 95% CI: 1.04, 2.30], and maternal occupational status [AOR = 2.31, 95% CI: 1.56, 3.42] were independently associated with wasting in the study area.

Conclusion

Wasting is a severe public health problem in Dabat District. Therefore, there is a need to strengthen the implementation of optimal breastfeeding practice and dietary diversity. In addition, improving the coverage of mothers’ postnatal vitamin-A supplementation is essential to address the burden of child wasting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Undernutrition is the most devastating problem affecting the majority of the world’s children [1]. That poor nutritional status during childhood has long–lasting scarring consequences [2]. Undernutrition diminishes the working capacity of an individual during adulthood [3], and it silently destroys the future socio-economic development of nations [2]. Ultimately, it causes the vicious cycle of intergenerational undernutrition [4].

Underweight, stunting, and wasting are the three main indicators used to define undernutrition [5], which is having a Z–score lower than two standard deviations as compared to the reference population of the same age and sex [6]. Low weight-for-height (WHZ ≤ −2 SD) is an indicator of wasting, which is generally associated with recent illness and child failure to gain weight [7].

Worldwide, 52 million children under five years of age are wasted [8] and most of the global burden of wasting (acute undernutrition) is found in developing countries [7, 9, 10]. Likewise, the magnitude of the problem is substantial and persistent in Sub–Saharan Africa (SSA) [11]. Different studies in Ethiopia reported a high prevalence of wasting among children aged under–five years [12–16]. The 2014 Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey report showed that, about 9% of children are wasted [17].

Causes of child undernutrition depend on complex interactions of various factors, such as socio–demographic, environmental, cultural, and political [18–20]. Many studies have been conducted to investigate the magnitude and predictors of wasting in Ethiopia [21, 22] and other parts of the world [23–27]. Findings revealed that household economic status [10, 17, 28, 29], mothers residence [29, 30], educational status [31], occupation [32] and nutritional status [7], child morbidity status [8, 31–33], sex, age [32, 34, 35], age of initiation into complementary feeding [14, 15], and birth interval [36] are associated with wasting.

Since the last two decades, Ethiopia has been thriving to improve the level of malnutrition in different segments of the population [37]. On the other hand, the magnitude and complications of acute undernutrition remain a public health problem in the country [17]. Wasting is among the leading nutritional problems, causing morbidity and mortality in children under five years of age [15]. Evidence based health and nutrition findings have a crucial role in improving the level of wasting and mortality reduction in children [38]. However, studies identifying factors associated with wasting among children aged under five years in Northwest Ethiopia are scarce. Thus, this study aimed at assessing factors associated with wasting among children aged under five years at Dabat District, Northwest Ethiopia. The findings from the study will provide evidences to programme managers and policymakers for designing and implementing appropriate interventions to mitigate the level of malnutrition and wasting in particular, among children aged under five years in Northwest Ethiopia.

Methods

Study setting

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted from May to June, 2015 at Dabat Health and Demographic Surveillance System (HDSS) site, located in Dabat District, northwest Ethiopia. The district has an estimated population of 145,458, living in 26 rural and 4 urban kebeles (smallest administration units Ethiopia). The inhabitants mainly depend on subsistence farming. The HDSS covers 67,385 people, living in thirteen kebeles (four urban and nine rural) selected by considering the different ecological zones (high land, middle land, and low land). The Dabat HDSS site has been operational since November, 1996.

Sampling procedure and study population

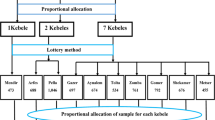

Initially, the study aimed at assessing the nutritional status and feeding practice of children aged 6–59 months at the Dabat HDSS site. Of the total thirteen kebeles in the HDSS, eight were selected by using the lottery method. Accordingly, all mothers with children aged 6–59 months and lived in the selected kebeles for at least six months were included in the study. For households with multiple children, only one was selected using the lottery method. Sample size was determined using Epi-info version 3.7 by considering the following assumptions; the prevalence of wasting in Ethiopia as 9% [17], 95% level of confidence, 5% margin of error, 10% non-response rate, and a design effect of 2. Thus, the minimum sample size of 844 was obtained. However, the 1184 eligible children found in the original survey were included in order to improve the power of the investigation.

Data collection instrument and procedures

Interviewer administered, pre-tested, and structured questionnaire was used to collect data. The questionnaire was designed with three major factors in mind. The first part was on socio-demographic and economic related characteristics of the child and family. The second part involved feeding patterns, morbidity status, and health care utilization related characteristics of the child, while the third section focused on hygiene and sanitation related characteristics of the household/family. To maintain the consistency of the data, the questionnaire was first translated from English to Amharic (the native language of the study area) and was retranslated to English by English language and public health experts. Fourteen data collectors and three field supervisors (working at Dabat DHSS) were recruited for the study. The recruits were given two days training on the objective of the study, ethical concerns, and data collection techniques. The tool was piloted on 5% of the total sample out of the study area. During the pre–test, the applicability of the data collection procedures was evaluated. The questionnaire was checked for completeness and clarity by the respective supervisors on a regular basis.

The anthropometric measurement was done according to the standardized procedures stipulated by the Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance (FANTA) Anthropometric Indicators Measurement Guide [39]. The stature of the child was measured using the seca vertical height scale (German, Serial No. 0123) with the child standing upright in the middle of the board. The child’s head, shoulders, buttocks, knees, and heels touched the vertical board. The length of a child (aged 6–23 months) was measured using a horizontal wooden length board in a recumbent position and read to the nearest 0.1 cm.

Child weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg by the seca beam balance (German, Serial No. 5755086138219) with a graduation of 0.1 kg and a measuring range of up to 25 kg. Weight was taken in light clothing and no shoes. Instrument calibration was done before weighing each child. Furthermore, the weighing scale was checked daily against the standard weight for accuracy. Each child’s height and weight measurements were repeated, and the mean value was calculated and recorded on the copies. Anthropometric-related data were transferred to the WHO Anthro Plus software version 1.0.4. The weight-for-height Z-score (WHZ) was calculated using the WHO Multicenter Growth Reference Standard. A child whose weight-for-height z score was less than −2 standard deviations (WFH < − 2 SD) from the reference population was defined as wasted [40].

Dietary diversity scores (DDSs) were estimated by using a 24-h recall method. Individual DDSs were meant to reflect the micronutrient adequacy of the diet. The scores were validated for several age/sex groups as proxy measures for macro and micronutrient adequacy of the diet. Furthermore, DDSs have positively correlated with the micronutrient density to complementary foods for infants and young children [41]. The scores were also used to monitor progress or target interventions at population levels [42]. The recall period of 24 h is the mostly chosen technique of many studies as it is less subject to recall bias, less cumbersome for respondents, and conforms to the recall period [43]. Moreover, the analysis of dietary diversity data based on a 24-h recall period is easier than other longer dietary assessment recall periods [44]. The mothers were requested to list out what food groups were consumed by their children in the previous 24–hours prior to the date of survey. The DDS of four is considered as the minimum acceptable dietary diversity; accordingly, a child with a DDS of less than four was classified as having poor dietary diversity; otherwise, it was considered to have good dietary diversity [45].

Data analysis

Data were entered into EPI-info version 3.5.3 and exported to the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20 for analysis. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies and proportions, were used to summarize the variables. Maternal employment status was categorized into three groups, i.e. housewife, farmer, and others (e.g. unemployed, student, and servants). Binary logistic regression was used to investigate factors associated with wasting. All those variables with a p-value of < 0.2 in the bi-variable analysis were entered into the multivariable regression analysis. The Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) with a 95% confidence interval was estimated to assess the strength of association, and a p-value of < 0.05 was used to declare statistical significance in the multivariable analysis.

Using the principal component analysis (PCA), household wealth index was computed by considering properties like, selected household assets and size of agricultural land. In the PCA, the Eigen value of greater than one, KMO distribution, and a communality value of greater than 0.5 were used to select variables for the final model. In the final model, the selected variables were summed and ranked into lowest, middle, and highest.

Results

The mean (Standard Deviation, ±SD) age of the children was 27.7 (±14.0) months. About 15.2% of the children were aged 6–11 months. About 30.1% and 32.9% of the mothers and fathers of the children attended formal education, respectively. More than fifty percent (52.2) of the households had five and less family members. A good proportion (69.4%) of the households accessed their food from their own farms (Table 1).

Almost all (99.3%) of the children were ever breastfed, about 52.3% initiated breastfeeding within one hour of delivery, while two-thirds (62.9%) of them remained exclusively breastfed for six months. About 37.2% and 17.9% of the participants had fever and diarrheal episodes, respectively. More than three-quarters (79.4%) of the children received vitamin-A supplementation, and one-third (35%) took a deworming tablet. The majority (94.1%) of the children had poor dietary diversity. Only a quarter (24.7%) and half (45.3%) of mothers received postnatal vitamin-A and prenatal iron-folate supplementation, respectively (Table 2).

About 36.1% of households used protected sources of water, and 28.7% had latrines. Nearly three-fourths of the mothers washed their hands after toilet, whereas almost all (95.9%) washed their hands before feeding their children (Table 3).

The overall prevalence of wasting was 18.2% [95% CI: 15.8, 20.3], of which 10.3% and 7.9% were moderately and severely wasted, respectively.

Determinants of wasting

The result of the multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that time for initiation into breastfeeding, maternal postnatal vitamin-A supplementation, and occupation status were identified independent determinants of wasting at 95% confidence intervals. Accordingly, children with poor dietary diversity were more likely to have wasting [AOR = 2.08, 95% CI: 1.53, 4.46] compared to those who had good dietary diversity. Similarly, increased odds of wasting were noted among children whose mothers initiated breastfeeding after one hour of delivery [AOR = 1.43, 95% CI: 1.04, 1.95] and received no postnatal vitamin-A supplementation [AOR = 1.55, 95% CI: 1.04, 2.30]. Furthermore, the odds of wasting were higher among mother engaged in other work categories [AOR = 2.31, 95% CI: 1.56, 3.42] compared to housewife mothers (Table 4).

Discussion

In this study, the prevalence of wasting was 18.2%, suggesting a severe public health problem according to the Nutrition Landscape Information System (NLIS) cut-off values [46]. The finding was consistent with the recent EDHS report [17], and other previous local studies, like East and West Gojjam (17.1-18.6%) [47], Somali Region (17.5%) [48], Bulehora District (13.4%) [49], and East Harargie (11.2%) [50]. A similarly high prevalence of wasting was reported from the three regions of Allahabad (10.6%) [51], Karnataka (16%) [52], and Bhubaneswar, India (23.3%) [53]. The high burden of wasting in these study settings may be explained in terms of the similarity that the majority of the participants share by living in rural areas. Obviously, poor child feeding practices and a high prevalence of food insecurity are the commonly reported determinants of wasting [47–50, 53], as documented in the rural communities of Ethiopia [51, 54].

However, the result was higher than what was reported from other developing countries, such as Ghana (4.7%) [55], Kenya (2.1%) [56], and Iran (0.7%) [57]. The disparities could be attributed to the better socio-economic status of the population in the latter study areas. In fact, children in better-off families have improved opportunity to get nutritious and diversified food [57]. On the other hand, compared to what was done in Kenya and Iran, this study involved a larger number of participants which might have contribution to the higher prevalence of wasting.

The result of the multivariate analysis revealed that late initiation of breastfeeding, poor dietary diversity, no postnatal vitamin–A supplementation, and maternal employment status were significantly and independently associated with wasting. Accordingly, the odds of wasting were higher among children with late initiation into breastfeeding. This is similar to various reports in Ethiopia and elsewhere [1, 8, 15, 24], confirming the fact that early initiation into breastfeeding helps the newborn to get the nutritional and protective benefits of the colostrum [58]. In addition, it promotes suckling, successful establishment, and maintenance of BF throughout infancy [59]. Despite its benefits, many mothers delay the initiation of breastfeeding, that is, only 43% of newborns in developing countries are put to the breast within one hour of birth. Establishing good breastfeeding practices in the first days is critical to the health and nutritional status of the infants. Also, it is one of the proven nutrition intervention for saving lives [60].

This study indicated that the likelihood of wasting was higher among children with poor DDSs. Poor dietary diversity, a proxy indicator of poor diet quality and nutrient intake of children [61], negatively influences the nutritional status of children [62, 63]. Providing nutrient-rich foods in sufficient quantity and quality starting at a child’s age of six months is one of the long-term and effective strategies to reduce child undernutrition [64, 65]. However, mother/caretaker IYCF knowledge is still low and a major problem in developing countries [66, 67]. As a result, children living in most developing countries are introduced directly to regular household diets made of cereal or starchy root crops [68] which are poor in micronutrient density [69].

The likelihood of developing wasting was high among children whose mothers were in other employment categories. Other studies also reported that children of unemployed mothers were at increased risk of developing wasting [5, 29, 30, 32]. This is further evidenced by the fact that unemployment of mothers is among the strong indicators of socio-economic resources of the household [70], sustaining a strong negative influence on household earnings and the level of food security [10]. It is clear that food insecure households have a limited capacity to afford and eat well-diversified diets [71]. This results in the family, particularly children eating foods poor in quality and quantity [28]. Furthermore, the powerlessness of women in the household is commonly documented to be the fate of unemployed mothers [72].

Similarly, the odds of wasting increased among children whose mothers received no postnatal vitamin-A supplementation. The concentration of vitamin-A and other micronutrients (iodine, thiamin, riboflavin and pyridoxine) in breast milk is dependent on the level of mother’s body store and dietary intake [73]. Hence, poor vitamin-A status of mothers at the time of pregnancy and postnatal period, determines the amount of vitamin-A in the breast milk [74, 75], for breast feeding a child. Child vitamin-A deficiency is correlated with a high risk of developing infectious diseases, including diarrhea and respiratory tract infections [76, 77], which are the commonly reported predictors of wasting [48–50]. Furthermore, postnatal visit also creates opportunity for mothers to get health and nutrition counseling, which is crucial to address their socio-cultural misconceptions on IYCF practice [78–80].

The study used a large sample size to show the burden of wasting in a well defined population . However, some of the limitations of the study should be considered. Firstly, the co-morbidity status of the child was conveyed only by information given by mothers/caregivers. This might be subjected to bias, as it may depend on the mothers/caretakers’ level of knowledge of the illness status of the child. Secondly, measurement of child feeding practice again relied on memory, so there was a possibility of recall bias.

Conclusion

The magnitude of wasting is high in Dabat District which suggest a severe public health concern in northwest Ethiopia. Wasting was associated with initiation of breastfeeding, dietary diversity, maternal postnatal vitamin-A supplementation, and employment status. Therefore, there is a need to strengthen implementation of the current IYCF strategy to improve the dietary diversity and breastfeeding practice. In addition, improving the coverage of mother's postnatal vitamin-A supplementation is essential to address childhood wasting.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COR:

-

Crude odds ratio

- DDS:

-

Dietary diversity score

- FANTA:

-

Food and nutrition technical assistance

- HDSS:

-

Health and demographic surveillance system

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- WHO:

-

World health organization

- WHZ:

-

Weight for height Z-score

References

UNICEF. WHO. Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices. Part 1 Definitions. Geneva: WHO; 2008.

Lomborg B. Global crises, global solutions: Cambridge university press. 2004.

Maluccio J, Adato M, Flores R, Roopnaraine T. Breaking the Cycle of Poverty: Nicaraguan Red de Protección Social. International Food Policy Research Institute brief (also available in Spanish). 2005.

Glewwe P, Miguel EA. The impact of child health and nutrition on education in less developed countries. Handb Dev Econ. 2007;4:3561–606.

Bloss E, Wainaina F, Bailey RC. Prevalence and predictors of underweight, stunting, and wasting among children aged 5 and under in western Kenya. J Trop Pediatr. 2004;50(5):260–70.

Bangladesh DHS. National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), Mitra and Associates, and Macro International (2009). Calverton, Maryland: Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2007.

Collins S, Dent N, Binns P, Bahwere P, Sadler K, Hallam A. Management of severe acute malnutrition in children. Lancet. 2006;368(9551):1992–2000.

Bank U. Levels and trends in child malnutrition: UNICEF-WHO-the world bank joint child malnutrition estimates. Washington: Bank U; 2012.

Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, LE C e, de Onis M, Ezzati M, Mathers C, Rivera J: Action against Hunger: Acute Malnutrition: A Preventable Pandemic; 2009. International Network 247 West 37th Street, Floor 10 New York, NY 10018 212–967–7800.

Van de Poel E, Hosseinpoor AR, Speybroeck N, Van Ourti T, Vega J. Socioeconomic inequality in malnutrition in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(4):282–91.

Vitolo MR, Gama CM, Bortolini GA, Campagnolo PD, Drachler ML. Some risk factors associated with overweight, stunting and wasting among children under 5 years old. J Pediatr. 2008;84(3):251–7.

Deribew A, Alemseged F, Tessema F, Sena L, Birhanu Z, Zeynudin A, et al. Malaria and under-nutrition: a community based study among under-five children at risk of malaria, south-west Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2010;5(5):e10775.

Teshome B, Kogi-Makau W, Getahun Z, Taye G. Magnitude and determinants of stunting in children underfive years of age in food surplus region of Ethiopia: the case of west gojam zone. Ethiopian J Health Dev. 2009;23(2):99–106.

Ying F. Malnutrition among children in southern Ethiopia: levels and risk factors. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2005;14(3):185–8.

Demissie S, Worku A. Magnitude and factors associated with malnutrition in children 6–59 months of age in pastoral community of Dollo Ado district, Somali region. Ethiopia Sci J Public Health. 2013;1(4):175–83.

Fentaw R, Bogale A, Abebaw D. Prevalence of child malnutrition in agro-pastoral households in Afar Regional State of Ethiopia. Nutr Res pract. 2013;7(2):122–31.

Central Statistical Authority [Ethiopia] and ORC Macro. Mini Ethiopia demographic and health survey. Addis Ababa: Ethiopia and Calverton; 2014.

Action against Hunger: Acute Malnutrition: A Preventable Pandemic; 2009. International Network 247 West 37th Street, Floor 10 New York, NY 10018 212–967–7800.

Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, Caulfield LE, De Onis M, Ezzati M, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet. 2008;371(9608):243–60.

Morris SS, Cogill B, Uauy R, Maternal Group CUS. Effective international action against undernutrition: why has it proven so difficult and what can be done to accelerate progress? The Lancet. 2008;371(9612):608–21.

Medhin G, Hanlon C, Dewey M, Alem A, Tesfaye F, Worku B, et al. Prevalence and predictors of undernutrition among infants aged six and twelve months in Butajira, Ethiopia: the P-MaMiE Birth Cohort. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):27.

Amsalu S, Tigabu Z. Risk factors for severe acute malnutrition in children under the age of five: A case–control study. Ethiopian J Health Dev. 2016;22(1):11–113.

Avachat SS, Phalke VD, Phalke DB. Epidemiological study of malnutrition (under nutrition) among under five children in a section of rural area. Pravara Med Rev. 2009;4(2):20–2.

Hien NN, Hoa NN. Nutritional status and determinants of malnutrition in children under three years of age in Nghean. Vietnam Pak J Nutr. 2009;8(7):958–64.

Olack B, Burke H, Cosmas L, Bamrah S, Dooling K, Feikin DR, et al. Nutritional status of under-five children living in an informal urban settlement in Nairobi, Kenya. J Health Popul Nutr. 2011;29(4):357–363.

Sengupta P, Philip N, Benjamin A. Epidemiological correlates of under-nutrition in under-5 years children in an urban slum of Ludhiana. Health Popul. 2010;33(1):1–9.

Islam MM, Alam M, Tariquzaman M, Kabir MA, Pervin R, Begum M, et al. Predictors of the number of under-five malnourished children in Bangladesh: application of the generalized poisson regression model. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):11.

Sharghi A, Kamran A, Faridan M. Evaluating risk factors for protein-energy malnutrition in children under the age of six years: a case–control study from Iran. Int J Gen Med. 2011;4:607–11.

Odunayo S, Oyewole A. Risk factors for malnutrition among rural Nigerian children. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2006;15(4):491.

Hien NN, Kam S. Nutritional status and the characteristics related to malnutrition in children under five years of age in Nghean. Vietnam J Prev Med Public Health. 2008;41(4):232–40.

Wondafrash M, Amsalu T, Woldie M. Feeding styles of caregivers of children 6–23 months of age in Derashe special district. Southern Ethiopia BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):235.

Oyekale A, Oyekale T. Do mothers’ educational levels matter in child malnutrition and health outcomes in Gambia and Niger. Soc Sci. 2009;4:118–27.

Rayhan MI, Khan MSH. Factors causing malnutrition among under five children in Bangladesh. Pak J Nutr. 2006;5(6):558–62.

Nandy S, Irving M, Gordon D, Subramanian S, Smith GD. Poverty, child undernutrition and morbidity: new evidence from India. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83(3):210–6.

Rahman A, Chowdhury S, Hossain D. Acute malnutrition in Bangladeshi children: levels and determinants. Asia-Pacific J Public health. 2009;21(3).

Wamani H, Åstrøm AN, Peterson S, Tumwine JK, Tylleskär T. Predictors of poor anthropometric status among children under 2 years of age in rural Uganda. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9(03):320–6.

ECA A, NEPAD W. The cost of hunger in Africa social and economic impact of child undernutrition in Egypt, Ethiopia, Swaziland and Uganda. Addis Ababa: ECA A, NEPAD W; 2013.

Bhutta ZA, Ahmed T, Black RE, Cousens S, Dewey K, Giugliani E, et al. What works? Interventions for maternal and child undernutrition and survival. The lancet. 2008;371(9610):417–40.

Cogill B. Anthropometric indicators measurement guide. 2003.

World Health Organization: Unicef. WHO child growth standards and the identification of severe acute malnutrition in infants and children: a joint statement by the World Health Organization and the United Nations Children's Fund. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009.

Hatloy A, Torheim L, Oshaug A. Food variety Ð a good indicator of nutritional adequacy of the diet? A case study from an urban area in Mali, West Africa. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1998;52:891–8.

Ruel M, Graham J, Murphy S, Allen L. Validating simple indicators of dietary diversity and animal source food intake that accurately reflect nutrient adequacy in developing countries. Report submitted to GL-CRSP. 2004.

Kennedy GL, Pedro MR, Seghieri C, Nantel G, Brouwer I. Dietary diversity score is a useful indicator of micronutrient intake in non-breast-feeding Filipino children. J Nutr. 2007;137(2):472–7.

Steyn N, Nel J, Nantel G, Kennedy G, Labadarios D. Food variety and dietary diversity scores in children: are they good indicators of dietary adequacy? Public Health Nutr. 2006;9(05):644–50.

Daelmans B, Dewey K, Arimond M. New and updated indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding. Food Nutr Bull. 2009;30(2_suppl2):S256–S62.

PROFILE C. Interpretation Guide. 2010.

Motbainor A, Worku A, Kumie A. Stunting is associated with food diversity while wasting with food insecurity among underfive children in East and West Gojjam Zones of Amhara Region. Ethiopia PloS One. 2015;10(8):e0133542.

Fekadu Y, Mesfin A, Haile D, Stoecker BJ. Factors associated with nutritional status of infants and young children in Somali Region, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):846.

Asfaw M, Wondaferash M, Taha M, Dube L. Prevalence of undernutrition and associated factors among children aged between six to fifty nine months in Bule Hora district. South Ethiopia BMC Public health. 2015;15(1):41.

Zewdie T, Abebaw D. Determinants of child malnutrition: empirical evidence from Kombolcha District of Eastern Hararghe Zone. Ethiopia Quarterly J Int Agri. 2013;52(4):357–72.

Kumar D, Goel N, Mittal PC, Misra P. Influence of infant-feeding practices on nutritional status of under-five children. Indian J Pediatr. 2006;73(5):417–21.

Basit A, Nair S, Chakraborthy K, Darshan B, Kamath A. Risk factors for under-nutrition among children aged one to five years in Udupi taluk of Karnataka, India: A case control study. Australas Med J. 2012;5(3):163–7.

Panigrahi A, Das SC. Undernutrition and Its Correlates among Children of 3–9 Years of Age Residing in Slum Areas of Bhubaneswar, India. Sci World J. 2014;2014:1–9.

Yeneabat T, Belachew T, Haile M. Determinants of cessation of exclusive breastfeeding in Ankesha Guagusa Woreda, Awi Zone, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2014;14(1):262.

Saaka M, Galaa SZ. Relationships between Wasting and Stunting and Their Concurrent Occurrence in Ghanaian Preschool Children. J Nutr Metab. 2016;2016:1–11.

Muchina E, Waithaka P. Relationship between breastfeeding practices and nutritional status of children aged 0–24 months in Nairobi, Kenya. African J Food Agric Nutr Dev. 2010;10(4):2358–378.

Mahyar A, Ayazi P, Fallahi M, Javadi THS, Farkhondehmehr B, Javadi A, et al. Prevalence of underweight, stunting and wasting among children in Qazvin. Iran Iran J Pediatr Soc. 2010;2(1):37–43.

Brownlee A. Breastfeeding, weaning & nutrition: the behavioral issues: US Agency for International Development Washington, DC; 1990.

Befum K, Dewen KG: Inpact of early initiation of excusive breastfeeding on newborn death. Alive Thrive Thech Brief. 2010(1):2–5.

Bhutta ZA, Das JK, Rizvi A, Gaffey MF, Walker N, Horton S, et al. Evidence-based interventions for improvement of maternal and child nutrition: what can be done and at what cost? Lancet. 2013;382(9890):452–77.

Moursi MM, Arimond M, Dewey KG, Trèche S, Ruel MT, Delpeuch F. Dietary diversity is a good predictor of the micronutrient density of the diet of 6-to 23-month-old children in Madagascar. J Nutr. 2008;138(12):2448–53.

Bukusuba J, Kikafunda J, Whitehead R. Nutritional status of children (6–59 months) among HIV-positive mothers/caregivers living in an urban setting of Uganda. African J Food Agric Nutr Dev. 2009;9(6):1345–364.

Tariku A, Woldie H, Fekadu A, Adane AA, Ferede AT, Yitayew S. Nearly half of preschool children are stunted in Dembia district, Northwest Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. Archives of Public Health. 2016;74(1):13.

FANTA. Developing and validating simple indicators of dietary quality and energy intake of infants and young children in developing countries: summary of findings from analysis of 10 data sets. In: Working group on infant and young child feeding indicators. Washington: Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance (FANTA) Project, Academy for Educational Development (AED); 2006.

Zongrone A, Winskell K, Menon P. Infant and young child feeding practices and child undernutrition in Bangladesh: insights from nationally representative data. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15(9):1697–704.

Bhutta ZA, Ahmed T, Black RE, Cousens S, Dewey K, Giugliani E, et al. What works? Interventions for maternal and child undernutrition and survival. Lancet. 2008;371(9610):417–40.

Ramakrishnan U, Nguyen P, Martorell R. Effects of micronutrients on growth of children under 5 y of age: meta-analyses of single and multiple nutrient interventions. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(1):191–203.

Marriott BP, White A, Hadden L, Davies JC, Wallingford JC. World Health Organization (WHO) infant and young child feeding indicators: associations with growth measures in 14 low‐income countries. Matern Child Nutr. 2012;8(3):354–70.

Dewey KG, Brown KH. Update on technical issues concerning complementary feeding of young children in developing countries and implications for intervention programs. Food Nutr Bull. 2003;24(1):5–28.

Abbi R, Christian P, Gujral S, Gopaldas T. The impact of maternal work status on the nutrition and health status of children. Food Nutr Bull. 1991;13(1):20–5.

Frongillo EA, de Onis M, Hanson KM. Socioeconomic and demographic factors are associated with worldwide patterns of stunting and wasting of children. J Nutr. 1997;127(12):2302–9.

Central Statistical Agency (CSA) Ethiopia. Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2011. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland: CSA and ORC Macro; 2012.

Allen L. Maternal micronutrient malnutrition: effects on breast milk and infant nutrition, and priorities for intervention. SCN News. 1994;11:21–4.

Underwood BA. Maternal vitamin A status and its importance in infancy and early childhood. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;59(2):517S–22S.

dos Santos Fernandes TF, Andreto LM, dos Santos Vieira CS, de Arruda IKG, da Silva Diniz A. Serum retinol concentrations in mothers and newborns at delivery in a public maternity hospital in Recife, Northeast Brazil. J Health Popul Nutr. 2014;32(1):28.

Akhtar S, Ahmed A, Randhawa MA, Atukorala S, Arlappa N, Ismail T, et al. Prevalence of vitamin A deficiency in South Asia: causes, outcomes, and possible remedies. J Health Popul Nutr. 2013;31((4):413.

Thornton KA, Mora-Plazas M, Marín C, Villamor E. Vitamin A deficiency is associated with gastrointestinal and respiratory morbidity in school-age children. J Nutr. 2014;144(4):496–503.

Bhandari N, Mazumder S, Bahl R, Martines J, Black RE, Bhan MK, et al. Use of multiple opportunities for improving feeding practices in under-twos within child health programmes. Health Policy Plan. 2005;20(5):328–36.

Pelto GH, Santos I, Gonçalves H, Victora C, Martines J, Habicht J-P. Nutrition counseling training changes physician behavior and improves caregiver knowledge acquisition. J Nutr. 2004;134(2):357–62.

Shi L, Zhang J. Recent evidence of the effectiveness of educational interventions for improving complementary feeding practices in developing countries. J Trop Pediatr. 2011;57(2):91–8.

Acknowledgment

First of all, the authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the study participants for their willingness to take part in the study. The authors’ heartfelt thanks will also go to University of the Gondar for the financially supporting the study.

Funding

This study was funded by the University of Gondar. The views presented in the article are of the authors and do not necessarily express the views of the funding organization. The University of Gondar was not involved in the design of the study, data collection, analysis, and interpretation.

Availability of data and materials

Data will be made available up on request of the primary author.

Authors’ contributions

AT conceived the study, coordinated the overall activity, and carried out the statistical analysis, drafted the manuscript. GAB conceived the study, coordinated the overall activity, and reviewed the manuscript. HW participated in drafting and reviewing the manuscript. MMW participated in the design of the study, and reviewed the manuscript. AGW participated in the design of the study and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Gondar. The IRB waived the need for written informed consent, considering that the study did not involve any invasive procedures and reporting of any response for intervention. An official permission letter was secured from the Dabat Research Center. Accordingly, all mothers were informed about the purpose of the study, and interview was held only with those who agreed to give verbal consent to participate. The right to participate or withdraw from the study at any time without any precondition was disclosed unequivocally. Moreover, the confidentiality of information was guaranteed by using code numbers rather than personal identifiers and by keeping the questionnaire locked.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Tariku, A., Bikis, G.A., Woldie, H. et al. Child wasting is a severe public health problem in the predominantly rural population of Ethiopia: A community based cross–sectional study. Arch Public Health 75, 26 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-017-0194-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-017-0194-8