Abstract

Background

Stunting has been the most pressing public health problem throughout the developing countries. It is the major causes of child mortality and global disease burden, where 80 % of this burden is found in developing countries. In the future, stunting alone would result in 22 % of loss in adult income. About 40 % of children under five-years were stunted in Ethiopia. In the country, about 28 % of child mortality is related to undernutrition. Thus, the aim of this study was to determine the prevalence and determinants of stunting among preschool children in Dembia district, Northwest Ethiopia.

Methods

A community based cross–sectional study was carried out in Dembia district, Northwest Ethiopia from January 01 to February 29, 2015. A multi-stage sampling followed by a systematic sampling technique was employed to reach 681 mother-child pairs. A pretested and structured questionnaire was used to collect data. After exporting anthropometric data to ENA/SMART software version 2012, nutritional status (stunting) of a child was determined using the WHO Multicenter Growth Reference Standard. In binary logistic regression, a multivariable analysis was carried out to identify determinants of stunting. The Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) with a 95 % confidence interval was computed to assess the strength of the association, and variables with a P-value of <0.05 in multivariable analysis were considered as statistically significant.

Results

A total 681 of mother-child pairs were included in the study. The overall prevalence of stunting was 46 % [95 % CI: 38.7, 53.3 %]. In multivariable analysis, the odds of stunting was higher among children whose families had no latrine [AOR = 1.6, 95 % CI: 1.1, 2.2)]. Likewise, children living in household with more than four family size [AOR =1.4, 95 % CI: 1.1, 1.9)] were more likely to be stunted.

Conclusions

This study confirms that stunting is a very high public health problem in Dembia district. The family size and latrine availability were significantly associated with stunting. Hence, emphasis should be given to improve the latrine coverage and utilization of family planning in the district.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Stunting, chronic undernutrition, is resulted from long-term exposure to restricted nutrient supply and frequent infection [1]. Though changes in eating patterns and lifestyles, and economic development have contributed to decline in rates of childhood stunting in the world [1, 2], it has been the most pressing public health problem throughout the developing countries [3–5]. According to the recent global estimates, 165 million (26 %) children under 5 years are stunted [6]. More than 90 % of the world’s stunted children are living in Africa and Asia, with the prevalence of 36 % and 27 %, respectively [7].

Childhood stunting is associated with poor cognition and school performance [8, 9]. Besides to this, it poses adverse functional consequences during adolescent and adulthood period, such as low adult wages, lost productivity, and overweight, obesity, and nutrition-related chronic diseases [3, 8]. Particularly, stunting alone would result in 22 % of loss in adult income, however its impact worsen when it is coupled with poverty, which causes 30.1 % of loss in adult income [7]. Furthermore, stunting is one of the major causes of child mortality and global disease burden, where 80 % of the burden is found in developing countries [10].

The government of Ethiopia has implemented a comprehensive nutritional programs over the past decades to improve the nutritional status of children [11, 12]. Accordingly, the country has made substantial improvements in reduction of the burden of childhood stunting. However, about 40 % of children under five–years were still stunted [13], which conformed a very high public health significance when compared with the WHO threshold level [14]. Ethiopia also exhibited the highest burden of child mortality and morbidity [15], of which about 28 % of this mortality is related to undernutrition. In addition, sixteen percent of all repetitions in primary school are also associated with stunting [16].

Child growth is the result of complex and interwoven factors which mainly related to the socioeconomic, health, and dietary habit related characteristics of children [10, 13, 17, 18]. Among the factors which were commonly reported by different studies; mother’s nutritional status, child’s sex, parental education, place of residence, child caring practice, access to health care, latrine availability, and source of drinking water were significantly associated with stunting [19–23]. Particularly, the odds of stunting was higher among children whose mothers were illiterate [20, 24, 25]. Likewise, the likelihood of stunting was higher among children whose parents were in the lowest socio-economic status [26–28].

Hence, showing the magnitude of stunting will have vital importance to address the adverse consequences of stunting among children. Determining the magnitude of stunting among preschool children, the new entrants of school in the near future, might provide a baseline evidence for better estimation of functional consequences, including poor cognition, however, most of the studies in the country merely focused on children aged 6–59 months [10, 29–31]. Thus, the study aimed to assess the prevalence and determinants of stunting among preschool children (24–59 months) in Dembia district.

Methods

Study design and setting

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted from January 01 to February 29, 2015 in Dembia district, Northwest Ethiopia. The district has 45 kebeles (smallest administrative units), of which 40 are rural. A total of 270,994 people lived the district [32]. As per the 2015 district health office report, 18,006 preschoolers also lived in the district, and ten Health Centers and forty Health Posts provide health service to the community . Surrounded by the great Lake Tana, the district is a well-known malaria endemic area. The residents are by and large subsistence farmers cultivating mainly cereals, legumes, and spices.

Sample size, sampling procedure, and study participants

Preschool children who lived in the district for at least six months were included in the study. The minimum sample size was determined using the formula to estimate single population proportion with the following assumptions: the expected prevalence of stunting as 50 %, a 95 % confidence level, and 5 % margin of error (d). Finally, a minimum sample size of 692 was obtained after anticipating a 20 % non-response rate and adjusting design effect of 1.5. A multi-stage sampling followed by a systematic sampling technique was employed to select the study subjects. Initially, nine representative kebeles in the district (1 urban and 8 rural) were selected using the lottery. The total number of preschool children (3477) living in the selected kebeles was obtained from the district health office and used to calculate the sampling fraction (k). After a proportional allocation to each kebele, the systematic sampling technique was employed. In those households with more than one eligible study subject, lottery was used to select only one child. When mother-child pairs were not available at the time of data collection, two repeated visits were made.

Data collection instruments and procedure

Data were collected through a face-to-face interview by using a pretested and structured questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of socio-demographic and economic characteristics, health, and feeding pattern related information. To maintain its consistency, the questionnaire was first translated from English to Amharic, the native language of the study area, and was retranslated to English by professional translators (English language expertise). Two experienced public health experts and 12 trained data collectors (2 Public health officers and 10 clinical nurses) were recruited for supervision and data collection, respectively. The investigators coordinated the overall activities of data collection. The tool was piloted on 5 % of the sample size outside the study area. During the pre-test, the acceptability and applicability of the procedures and tools were evaluated. Household wealth index was computed using a composite indicator for urban and rural residents by considering properties like, livestock ownership, selected household assets, size of agricultural land, and the quantity of crop production. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to categorize the household living standards into lowest, middle, and highest.

Anthropometric measurement

Child weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg by the seca beam balance (German, Serial No. 5755086138219) with graduation of 0.1 kg and a measuring range of up to 25 kg. Weight was taken with light clothing and no shoes. Instrument calibration was carried out before weighing each child. Furthermore, the weighing scale was checked against a standard weight for its accuracy on a daily basis.

Height was measured using the seca vertical height scale (German, serial No. 0123) standing upright in the middle of the board. The child’s head, shoulders, buttocks, knees, and heels touch the vertical board. Most of study participants’ birth date was extracted from the Immunization status certificate (immunization card) of the child. However, for nine study subjects, their age was determined based on the information given by the mother/caretaker of the child.

Anthropometric related data of a child were transferred to the ENA/SMART software version 2012 and the Z-scores of indices, Height-for-Age Z-scores (HAZ), was calculated using the WHO Multicenter Growth Reference Standard. The child was classified as stunted if his/her z score was less than −2SD; otherwise, he/she was well-nourished (≥ − 2 Z score) [33].

Assessment of dietary diversity

In Dembia district, there was low intra individual variability regarding the dietary pattern of children. Accordingly, prolonging the reference period in capturing the dietary habit of the study participants may not bring a substantial difference. Thus, Dietary Diversity Score (DDS) of the child was determined using 24-hours recall method. Mothers were asked to list all food item consumed by the child in the previous 24 hours preceding the survey. In case of mixed dish, the ingredients of the food items were listed by the mother. Then, reported food items were classified into seven food groups, as starchy staples (grains, roots, and tubers); legumes, nuts and seeds; vitamin-A rich fruits and vegetables; other fruits and vegetables; egg; dairy products (milk, yoghurt, and cheese); and flesh foods (meat, fish, poultry, and organ meats) [34]. Considering four food groups as the minimum acceptable dietary diversity, a child with a DDS of less than four was classified as poor dietary diversity.

Data processing and analysis

Data were entered into EPI-INFO version 3.5.3 and analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies and proportions was used to summarize the study variables. A binary logistic regression was fitted, variables with a p-values of < 0.2 in the bivariable analysis were entered in the multivariable analysis to control the possible effect of confounders. In multivariable analysis, backward selection method was used to identify factors associated with stunting. The Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) with a 95 % confidence interval was estimated to assess the strength of association, and a p-value of < 0.05 was used to declare the statistical significance in the multivariable analysis.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Gondar. An official permission letter was secured from Dembia District Health Office. All mothers or caretakers of children were informed about the purpose of the study, and interview was held only with those who agreed to give a written consent to participate. Uneducated mothers affirmed their consent by their thumbprint. The right of a participant to withdraw from the study at any time, without any precondition was disclosed unequivocally. Moreover, the confidentiality of information obtained was guaranteed by all data collectors and investigators by using code numbers rather than personal identifiers and by keeping the questionnaire locked.

Results

Socio-demographic and economic characteristics of study participants

A total of 681 mother-child pairs were included in the study, making a response rate of 98.4 %. The mean age (±SD) of the children was 41.58 months (±11.27), and slightly more than half (53.6 %) of them were male. Almost all (93.1 %) of the participants were living in the rural kebeles of Dembia district. In the study area, nearly one-third (30 %) of the households (HHDs) had ≥7 family members. The majorities (95.4 %) of the mothers were housewives, uneducated (77.1 %), and gave their first birth before the age of 20 (63.1 %) (Table 1).

Health and nutrition related characteristics of study participants

The majority (85.8 %) of the mothers had at least one Antenatal Care (ANC) visit for the index child, but around one third (29.9 %) of them gave birth at heath facilities. Most (82.5 %) of the children had a dietary diversity score of below four. Nearly three-fourths (70.3 %) of the mothers initiated breast feeding timely, within an hour of delivery, and a significant proportion of the mothers (65.9 %) initiated complementary feeding at the sixth month (Table 2). The dietary pattern of children in the district mainly depends on starchy staples (99.3 %) and legumes (94.9 %), but only few percentage (0.3 %, 0.4 %, and 0.6 %, respectively) of children ate egg, vitamin-A rich fruits or vegetables, and meat in the previous 24-hours preceding the date of survey (Fig. 1).

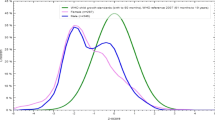

Prevalence of stunting among preschool children

The overall prevalence of stunting in the district was 46 % [95 % CI: 38.7, 53.3 %], of which about 49.8 % of children were severely stunted (Fig. 2).

Determinant factors of stunting among preschool children

In bivariable logistic regression analysis, the family size, source food, and latrine availability were significantly associated with stunting. However, in the multivariable logistic regression analysis, household size and latrine availability remained significantly and independently associated with stunting. Accordingly, the likelihood of stunting among children whose family had no latrine was 60 % [AOR = 1.6, 95 % CI: 1.1, 2.2)] more as compared to their counterparts who had latrine. Likewise, the odds of stunting was 40 % [AOR =1.4, 95 % CI: 1.1, 1.92)] higher among children whose parents had a family size of more than four compared with children whose parents had a family size of less or equal to four (Table 3).

Discussion

Assessment of growth is the single measurement that best defines the nutritional and health status of children, and provides an indirect measurement of the quality of life for the entire population [35]. Stunting measures cumulative deficient of growth associated with the long-term factors, including insufficient dietary intake, frequent infections, poor feeding practices over a sustained period of time, and low socioeconomic status of the households [36]. Thus, this study assessed the prevalence and determinants of stunting among preschool children.

The prevalence of stunting was high (46 %) in the district, and confirms very high public health significance [14]. The result was consistent with the mini-Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey report (40 %) [13], and the average estimate of stunting for developing countries (42.7 %) [37]. Likewise, the finding was in agreement with the study reports of other developing countries, such as India (43 %) [38], Nigeria (44.9 %) [39], and Bangladesh (39.5 %) [40]. This is probably due to contextual similarities in socio- demographic and economic characteristics, and feeding pattern of children of the study areas.

However, the prevalence of stunting was highest compared with the study findings in Somali, Ethiopia [30], Ghana (27 %) [41], China (27 %) [42], and Iran (11.5 %) [43]. This discrepancy could be attributed to the difference in age of children included in the studies, in which the latter studies included children less than 24 months while only children aged 24–59 months were included in the current study. However, children found in this age category were less likely to be stunted compared with children aged beyond 24 months [41, 44]. Hence, the study included the older children; the magnitude of stunting was overestimated. In contrast to the latter abroad studies, most of the mothers were illiterate and housewife in the study area. The low maternal educational status was associated with higher odds of childhood stunting [15, 39, 40, 45]. Moreover, low educational status, particularly among household heads negatively affects the household food security status [46]. Though housewife mothers had better time to care their child, in the context of Ethiopia, most of them were not engaged in productive work compared with mothers in other employment status. However, almost all of the mothers were housewives in the study area, of which more than three-fourth of them were illiterate.

The result of the study also demonstrated that, large family size increases odds of having stunting in preschool children. Similar findings were reported in different studies [47–51]. This might be related to the complex interaction between the household food security status, family size, and food consumption pattern of children. As it was revealed by other studies, large family size negatively affects the household food security status mainly through increasing the food expenditure per capita, thereby posing difficulties in securing the per-capita food availability in larger households [46, 52]. Food insecurity hardly affects the household food consumption pattern though forcing them to shift in purchasing low quality food, skip meal, and relay on monotonous diet. However, such poor dietary habits [53], and poor household food security status were associated with stunted growth [54–56].

The likelihood of stunting among children whose families had no latrine was higher as compared to those who had. This finding was concurrent with the findings reported from developing countries [57–60]. This could be related to the importance of latrine availability in promoting optimal hygiene and sanitation in the household and the community at large. Improved hygiene and sanitation is found with reduced risk of childhood stunting, which mainly operates through reducing risk of recurrent diarrhea and other gastro-intestinal related infections [61, 62].

Some of the limitations of this study should be noted and taken into consideration. First, since the study utilized a cross-sectional study design, findings could not show the casual relationship between stunting and other independent variables. Second, there is a potential recall bias among respondents while answering questions related to events happened in the past, such as child feeding practices. Nevertheless, maternal nutritional conditions were potential confounders of stunting in children, the study did not gathered information. Lastly, we didn’t capture information regarding the utilization of latrine.

Conclusions

This study confirms that stunting is a very high public health problem in Dembia district. The household family size and latrine availability were significantly associated with stunting. Hence, emphasis should be given to improve the latrine coverage and utilization of family planning in the district.

References

Stevens GA, Finucane MM, Paciorek CJ, Flaxman SR, White RA, Donner AJ, et al. Trends in mild, moderate, and severe stunting and underweight, and progress towards MDG 1 in 141 developing countries: a systematic analysis of population representative data. Lancet. 2012;380(9844):824–34.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Improving child nutrition: the achievable imperative for global progress. United Nations Children's Fund; 2013.

Victora CG, Adair L, Fall C, Hallal PC, Martorell R, Richter L, Sachdev HS, Maternal Group CUS. Maternal and child undernutrition: consequences for adult health and human capital. Lancet. 2008;371(9609):340–57.

Food and Agricultural Organization, United Nations. Undernourishment around the world, The state of food insecurity in the world 2004. Rome: The Organization; 2004.

De Onis M, Blössner M, Borghi E. Prevalence and trends of stunting among pre-school children, 1990–2020. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15(01):142–8.

Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, Bhutta ZA, Christian P, De Onis M, Ezzati M, Grantham-McGregor S, Katz J, Martorell R. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2013;382(9890):427–51.

De Onis M, Brown D, Blossner M, Borghi E. Levels and trends in child malnutrition. UNICEF-WHO-The World Bank joint child malnutrition estimates; 2012.

Kordas K, Lopez P, Rosado JL, Vargas GG, Rico JA, Ronquillo D, Cebrián ME, Stoltzfus RJ. Blood lead, anemia, and short stature are independently associated with cognitive performance in Mexican school children. The Journal of nutrition. 2004;134(2):363–71.

Mendez MA, Adair LS. Severity and timing of stunting in the first two years of life affect performance on cognitive tests in late childhood. J Nutr. 1999;129(8):1555–62.

Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A, Vander Hoorn S, Murray CJ. Selected major risk factors and global and regional burden of disease. Lancet. 2002;360(9343):1347–60.

Government of the Federal Democratic and Republic of Ethiopia: National Nutrition Program June 2013-June 2015

Federal Ministry of Health. Ethiopian National Strategy on Infant and Young Child Feeding; 2004

Central Statistical Authority [Ethiopia] and ORC Macro. Mini Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2014. Addis Ababa. Maryland: Ethiopia and Calverton; 2014.

World Health Organization. Nutrition Landscape Information System (NLIS). Country profile indicators: interpretation guide Geneva: WHO; 2010.

Central Statistical Authority [Ethiopia] and ORC Macro. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Addis Ababa. Maryland: Ethiopia and Calverton; 2011.

State Minister of Health, Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, The Cost of HUNGER in Ethiopia, The Social and Economic Impact of Child Undernutrition in Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2009

Rawe K. A Life Free From Hunger: Tackling child malnutrition. 2012.

Najm-Abadi S. Risk analysis of growth failure in under-5-year children. Arch Iran Med. 2004;7(3):195–200.

Ayaya S, Esamai F, Rotich J, Olwambula A. Socio-economic factors predisposing under five-year-old children to severe protein energy malnutrition at the Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital, Eldoret, Kenya. East Afr Med J. 2004;81(8):415–21.

Wamani H, Åstrøm AN, Peterson S, Tumwine JK, Tylleskär T. Predictors of poor anthropometric status among children under 2 years of age in rural Uganda. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9(03):320–6.

Pongou R, Ezzati M, Salomon JA. Household and community socioeconomic and environmental determinants of child nutritional status in Cameroon. BMC Public Health. 2006;6(1):98.

Mostafa Jr KS, Rosliza A, Aynul M. Effects of Wealth on Nutritional Status of Pre-school Children in Bangladesh. Malays J Nutr. 2010;16(2):219–32.

Hong R, Mishra V. Effect of wealth inequality on chronic under-nutrition in Cambodian children. J Health Pupul Nutr. 2006;24:89–99.

Christiaensen L, Alderman H. Child Malnutrition in Ethiopia: Can Maternal Knowledge Augment the Role of Income?*. Econ Dev Cult Chang. 2004;52(2):287–312.

Harishankar DS, Dabral S, Walia D. Nutritional status of children under 6 years of age. Indian J Prev Soc Med. 2004;35:156–62.

Bose K, Bisai S, Chakraborty J, Datta N, Banerjee P. Extreme levels of underweight and stunting among pre-adolescent children of low socioeconomic class from Madhyamgram and Barasat, West Bengal, India. Coll Antropol. 2008;32(1):73–7.

Peiris T, Wijesinghe D. Nutritional Status of under 5 Year-Old Children and its Relationship with Maternal Nutrition Knowledge in Weeraketiya DS division of Sri Lanka. Trop Agric Res. 2010;21(4):330–9.

Getahun Z, Urga K, Genebo T, Nigatu A. Review of the status of malnutrition and trends in Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2001;15(2):55–74.

Zewdu S. Magnitude and factors associated with malnutrition of children under five years of age in Rural Kebeles of Haramaya, Ethiopia. Harar Bull Health Sci. 2012;4:221–32.

Fekadu Y, Mesfin A, Haile D, Stoecker BJ. Factors associated with nutritional status of infants and young children in Somali Region, Ethiopia: a cross- sectional study. BMC Public health. 2015;15:846.

Asfaw M, Wondaferash M, Taha M, Dube L. Prevalence of undernutrition and associated factors among children aged between six to fifty nine months in Bule Hora district, South Ethiopia. BMC Public health. 2015;15:41.

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia population Census Commission. Summary and statistical report of 2007 population and housing census. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2007.

World Health Organization, UNICEF. WHO child growth standards and the identification of severe acute malnutrition in infants and children: joint statement by the World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund. 2009.

WHO. Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices PArt 3 Country Profiles. 2010.

Chang S, Walker S, Grantham‐McGregor S, Powell C. Early childhood stunting and later behaviour and school achievement. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2002;43(6):775–83.

Caulfield LE, de Onis M, Blössner M, Black RE. Undernutrition as an underlying cause of child deaths associated with diarrhea, pneumonia, malaria, and measles. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(1):193–8.

Muller O, Krawinkel M. Malnutrition and health in developing countries. CMAJ-Can Med Assoc J. 2005;173(3):279–86.

Sinha NK, Maiti K, Samanta P, Das DC, Banerjee P. Nutritional status of 2–6 year old children of Kankabati grampanchayat, Paschim Medinipur district. India: West Bengal; 2012.

Aliyu AA, Oguntunde OO, Dahiru T, Raji T. Prevalence and Determinants of Malnutrition among Pre-School Children in Northern Nigeria. Pak J Nutr. 2012;11(11):1092–5.

Jesmin A, Yamamoto SS, Malik AA, Haque MA. Prevalence and determinants of chronic malnutrition among preschool children: a cross-sectional study in Dhaka City, Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr. 2011;29(5):494.

Darteh EK, Acquah E, Kumi-Kyereme A. Correlates of stunting among children in Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):504.

Jiang Y, Su X, Wang C, Zhang L, Zhang X, Wang L, Cui Y. Prevalence and risk factors for stunting and severe stunting among children under three years old in mid‐western rural areas of China. Child Care Health Dev. 2015;41(1):45–51.

Mahyar A, Ayazi P, Fallahi M, Javadi THS, Farkhondehmehr B, Javadi A, Kalantari Z. Prevalence of Underweight, Stunting and Wasting Among Children in Qazvin, Iran. Iran J Pediatr Soc. 2010;2(1):37–43.

Bloss E, Wainaina F, Bailey RC. Prevalence and Predictors of Underweight, Stunting, and Wasting among Children Aged 5 and Under in Western Kenya. J Trop Pediatr. 2004;50(5):260–70.

Avachat SS, Phalke VD, Phalke DB. Epidemiological study of malnutrition (under nutrition) among under five children in a section of rural area. Pravara Med Rev. 2009;4(2):20–2.

Gebre GG. Determinants of food insecurity among households in Addis Ababa city, Ethiopia. Interdisciplin Descript Complex Sys. 2012;10(2):159–73.

Md O, Frongillo EA, Blössner M. Is malnutrition declining? An analysis of changes in levels of child malnutrition since 1980. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(10):1222–33.

Gorstein J, Sullivan K, Yip R, De Onis M, Trowbridge F, Fajans P, Clugston G. Issues in the assessment of nutritional status using anthropometry. Bull World Health Organ. 1994;72(2):273.

Hamidu J, Salami H, Ekanem A, Hamman L. Prevalence of protein-energy malnutrition in Maiduguri, Nigeria. Afr J Biomed Res. 2003;6(3).

Rabasa A, Omatara B, Padonu M. Assessment of nutritional status of children in a Sub-Saharan rural community with reference to anthropometry. Sahel Med J. 1998;1(1):15.

Kabir M, Ilyasu Z, Abubakar IS, Also U. Factors associated with nutritional status of preschool children in Danmaliki village. Kano state, Northern Nigeria. J Prim Care Commun Health. 2003;15:30–3.

Olayemi AO. Effects of Family Size on Household Food Security in Osun State, Nigeria. Asian Econ Soc Soc. 2012;2(2):2224–4433.

JH Rah NA, Semba R, Pee S, Bloem M, Campbell A, Moench-Pfanner R, Sun K, Badham J, Kraemer K. Low dietary diversity is a predictor of child stunting in rural Bangladesh. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64:1393–8.

Thamilini J, Silva KDRR, Jayasinghe JMUK. Prevalence of Stunting among Pre-school Children in Food Insecure Rural Households in Sri Lanka. Trop Agric Res. 2015;26(2):390–4.

Ajao K, Ojofeitimi E, Adebayo A, Fatusi A, Afolabi OT. Influence of family size, household food security status, and child care practices on the nutritional status of under-five children in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2010;14(4):117–26.

Ali D, Saha KK, Nguyen PH, Diressie MT, Ruel MT, Menon P, Rawat R. Household Food Insecurity Is Associated with Higher Child Undernutrition in Bangladesh, Ethiopia, and Vietnam, but the Effect Is Not Mediated by Child Dietary Diversity. J Nutr. 2013;143:1–7.

Medhin G, Hanlon C, Dewey M, Alem A, Tesfaye F, Worku B, et al. Prevalence and predictors of undernutrition among infants aged six and twelve months in Butajira, Ethiopia: the P-MaMiE birth cohort. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:27.

USAID (2007) Nutritional status and its determinants in Southern Sudan.

Monteiro CA, Benicio MHD, Conde WL, Konno S, Al L, Barrosb AJD, Victorab CG. Narrowing socioeconomic inequality in child stunting: the Brazilian experience, 1974–2007. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:305–11.

Willey BA, Cameron N, Norris SA, Pettifor JM, Griffiths PL. Socioeconomic predictors of stunting in preschool children –a population-based study from Johannesburg and Soweto. S Afr Med J. 2009;99:450–6.

Gn F, Gunther I, Hill K. The effect of water and sanitation on child health: evidence from the demographic and health surveys 1986–2007. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:1196–204.

Rah JH, Cronin AA, Badgaiyan B, Aguayo VM, Coates S, Ahmed S. Household sanitation and personal hygiene practices are associated with child stunting in rural India: a cross-sectional analysis of surveys. BMJ Open. 2015;5, e005180.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to those children and their mothers for their willingness and positive cooperation for being part of the study. The authors’ heartfelt thanks will also go to the University Of Gondar for the financial support of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution

Conceived and designed the experiments AT AAA ATF, Performed the experiments AT AF ATF, Analyzed the data AT SY HW, Wrote the paper AT AAA ATF HW SY, Approved the proposal with some revisions AT AAA ATF AF. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Tariku, A., Woldie, H., Fekadu, A. et al. Nearly half of preschool children are stunted in Dembia district, Northwest Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. Arch Public Health 74, 13 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-016-0126-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-016-0126-z