Abstract

We study the Stokes problem for the incompressible fluid with mixed nonlinear boundary conditions of subdifferential type. The latter involve a unilateral boundary condition, the Navier slip condition, a nonmonotone version of the nonlinear Navier–Fujita slip condition, and the threshold slip and leak condition of frictional type. The weak form of the problem leads to a new class of variational–hemivariational inequalities on convex sets for the velocity field. Solution existence and the weak compactness of the solution set to the inequality problem are established based on the Schauder fixed point theorem.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In this paper we study the Stokes problem for the incompressible fluid with mixed boundary conditions in a bounded domain of dimension two and three. The problem is formulated as a variational-hemivariational inequality of elliptic type involving both convex and locally Lipschitz, generally nonconvex, superpotentials. The main results concern the existence and compactness of the solution set.

We are motivated by the Stokes system with a frictional type boundary condition with the slip bound threshold value depending on the solution. Such a system has been treated in [10, 11] by the mixed variational formulation with the Lagrange multipliers and then applied to deal with optimum design problems. As mentioned in these papers, it was experimentally observed that the slip bound may depend on the solution itself, e.g., on values of the tangential component of the velocity. This situation may appear in several practical models of flows of polymer melts, blood flow in a vein, fluids on hydrophobic surfaces, problems with multiple interfaces, etc. The simplest threshold slip condition can be described by the Tresca-like condition when the threshold bound is given a priori and it is modeled by a convex potential, see [7, 9]. Note that when the slip bound depends on the solution, the model is more complicated, see [11, 14, 15, 17] and the non-stationary case in [8].

The main novelties of the paper are the following. First, we consider a generalization of slip and leak boundary condition of frictional type on diverse parts of the wall of the domain. For the slip condition we study the Clarke subgradient multivalued condition which, in contrast to [17], depends on the tangential velocity. The leak boundary condition can be governed by any convex and lower semicontinuous potential involving the normal velocity. Second, we have supplemented the model with an outflow unilateral boundary condition introduced just recently in [31]. This makes the Stokes problem more involved since the resulting variational-hemivariational inequality has an additional set of unilateral constraints. Third, in comparison with [10, 11], our approach and the proof is different and combines a recent result from the theory of variational–hemivariational inequalities and the Schauder fixed point theorem. In the proof of existence of solution, our main goal is to explore under which conditions concerning coefficients in slip and leak boundary conditions solutions to the Stokes system depend continuously on variations of parameters.

The important feature of the model is the nonlinearity of the form \(k \partial j\). In such a case we cannot deal with a purely hemivariational inequality since there is not, in general, a potential G with \(G = k \partial j\). This type of nonlinearity appears in the model twice: in the nonmonotone slip boundary condition which is described by the Clarke generalized gradient, and in the generalized leak boundary condition of frictional type governed by the subdifferential of the convex function. The slip bound function k depends on the (norm of the) solution, while the potential \(j \colon \mathbb{R}^{d} \to \mathbb{R}\) is a locally Lipschitz function and ∂j stands for its generalized subgradient. We mention that it is an interesting open problem to generalize the results of this paper to non-Newtonian fluids with various nonlinear constitutive law.

We note that the variational and hemivariational inequalities have been used to solve the fluid flow problems in [18, 19, 22] for the stationary models and in [6] for the evolutionary problems.

The paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2 we shortly recall our notation and preliminary results. Section 3 contains the classical and variational formulations of the Stokes problem and the statement of the existence theorem. Its proof is delivered in Sect. 4. Finally, in Sect. 5 we demonstrate the weak compactness of the solution set.

2 Preliminary material

In this section we recall the standard notation and definitions from [1, 3, 4, 20, 21].

Throughout the paper, given a Banach space X, we denote by \(X^{*}\) its dual space, by \(\| \cdot \|_{X}\) a norm in X, and by \(\langle \cdot,\cdot \rangle _{X^{*}\times X}\) the duality brackets between \(X^{*}\) and X. For simplicity of notation, when no confusion arises, we often skip the subscripts. We use the notation \(x_{n} \to x\) and \(x_{n} \rightharpoonup x\), respectively, to denote the strong convergence and weak convergence in various spaces. By \(\mathcal{L}(X_{1}, X_{2})\) we denote the space of linear and bounded operators from a normed space \(X_{1}\) to a normed space \(X_{2}\) endowed with the operator norm \(\|\cdot \|_{\mathcal{L}(X_{1}, X_{2})}\). Given a set \(D \subset X\), we set \(\| D \|_{X} = \sup \{ \| x \|_{X} \mid x \in D \}\).

A single-valued operator \(A \colon X \to X^{*}\) is pseudomonotone if it is bounded (it maps bounded subsets of X into bounded subsets of \(X^{*}\)), and if \(u_{n} \rightharpoonup u\) in X and \(\limsup \langle A u_{n}, u_{n} -u \rangle \le 0\) imply \(\langle A u, u - v \rangle \le \liminf \langle A u_{n}, u_{n} - v \rangle \) for all \(v \in X\). Equivalently, a single-valued operator A is pseudomonotone if and only if it is bounded, and \(u_{n} \rightharpoonup u\) in X together with \(\limsup \langle Au_{n},u_{n}-u \rangle \leq 0\) yields \(\lim \langle Au_{n}, u_{n}-u \rangle =0\) and \(Au_{n} \rightharpoonup Au\) in \(X^{*}\).

Let \(\varphi \colon X \to \mathbb{R}\cup \{ +\infty \}\) be a proper, convex, and lower semicontinuous function. The mapping \(\partial \varphi \colon X \to 2^{X^{*}}\) defined by

is called the convex subdifferential of φ. An element \(x^{*} \in \partial \varphi (x)\) is called a subgradient of φ in x. Let \(h \colon X \to \mathbb{R}\) be a locally Lipschitz function on a Banach space X. The generalized (Clarke) directional derivative of h at \(x \in X\) in the direction \(v \in X\) is defined by

The generalized (Clarke) gradient of h at x, denoted by \(\partial h (x)\), is a subset of the dual space \(X^{*}\) given by

Finally, we recall an existence and uniqueness result for a class of abstract variational–hemivariational inequalities. Let X be a reflexive Banach space. Given an operator \(A \colon X \to X^{*}\), functions \(\varphi \colon K \times K \to \mathbb{R}\), \(j \colon X \to \mathbb{R}\), and a set \(K \subset X\), we consider the following problem.

Problem 1

Find an element \(u \in K\) such that

For this problem, we need the following hypotheses on the data.

\(\underline{H(A)}\): \(A \colon X \to X^{*}\) is a function such that

-

(i)

it is pseudomonotone,

-

(ii)

it is strongly monotone, i.e., there exists \(m_{A} > 0\) such that

$$\langle Av_{1} - Av_{2}, v_{1} - v_{2} \rangle \ge m_{A} \Vert v_{1} - v_{2} \Vert _{X}^{2}\quad \text{for all } v_{1}, v_{2} \in X. $$

\(\underline{H(\Phi )}\): \(\Phi \colon X \to \mathbb{R}\) is convex and lower semicontinuous.

\(\underline{H(J)}\): \(J \colon X \to \mathbb{R}\) is a function such that

-

(i)

J is locally Lipschitz,

-

(ii)

\(\| \partial J(v) \|_{X^{*}} \le c_{0} + c_{1} \| v \|_{X}\) for all \(v \in X\) with \(c_{0}\), \(c_{1} \ge 0\),

-

(iii)

there exists \(\alpha _{J} \ge 0\) such that \(J^{0}(v_{1}; v_{2} - v_{1}) + J^{0}(v_{2}; v_{1} - v_{2}) \le \alpha _{J} \| v_{1} - v_{2} \|_{X}^{2}\) for all \(v_{1}\), \(v_{2} \in X\).

\(\underline{H(K)}\): K is nonempty, closed and convex subset of X.

\(\underline{H(f)}\): \(f \in X^{*}\).

Recall the existence and uniqueness result for Problem 1.

Theorem 2

Assume \(H(A)\), \(H(\Phi )\), \(H(J)\), \(H(K)\), \(H(f)\) and the smallness condition

Then Problem 1has a unique solution \(u \in K\).

Theorem 2 represents a particular case of a result proved in [21], where the function Φ depends additionally on the solution. Further, in [21, Theorem 18], the authors required additionally that A is coercive. However, this assumption is redundant, since if A is strongly monotone, then A is coercive in the following sense:

for all \(v \in X\). Condition \(H(J)\)(iii) has been extensively used in the literature for hemivariational inequalities, see [20, 29], and it is equivalent to the relaxed monotone condition

for all \(z_{i} \in \partial J(v_{i})\), \(z_{i} \in X^{*}\), \(v_{i} \in X\), \(i = 1\), 2. Further, if J is a convex function, then \(H(J)\)(iii) or equivalently (3) holds with \(\alpha _{J} = 0\) and means that the (convex) subdifferential is a monotone map. In this case the smallness condition (1) holds trivially.

3 Formulation of the Stokes problem

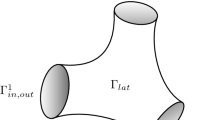

Let \(\Omega \subset \mathbb{R}^{d}\), \(d=2\), 3, be a connected Lipschitz bounded domain occupied by the incompressible fluid. The boundary \(\Gamma = \partial \Omega \) consists of smooth parts \(\Gamma _{0}\), \(\Gamma _{1}\), \(\Gamma _{2}\), and \(\Gamma _{3}\) such that \(\operatorname{meas}(\Gamma _{0}) > 0\), while the parts \(\Gamma _{1}\), \(\Gamma _{2}\), and \(\Gamma _{3}\) can be empty. The unit outward normal vector exists a.e. on the boundary and is denoted by ν. Moreover, \(\mathbb{M}^{d}\) denotes the class of symmetric \(d\times d\) matrices.

The classical formulation of the Stokes problem with mixed boundary conditions studied in this paper reads as follows.

Problem 3

Find a flow velocity \(\boldsymbol {u}\colon \Omega \to \mathbb{R}^{d}\), and a pressure \(p \colon \Omega \to \mathbb{R}\) such that

We give a short description of the Stokes system in Problem 3. The extra stress tensor \(\mathbb{S}\) is defined by the linear constitutive law \(\mathbb{S}(\mathbb{D}\boldsymbol {u}) = 2 {\widetilde{\mu }} \mathbb{D} \boldsymbol {u}\) in Ω, where μ̃ represents the dynamic viscosity, f is the volume force, and the deformation-rate tensor is given by \(\mathbb{D}\boldsymbol {u}= \frac{1}{2} (\nabla \boldsymbol {u}+ \nabla \boldsymbol {u}^{\top })\). To simplify presentation, we shall suppose in what follows that \(2 {\widetilde{\mu }} = \mu \). The divergence free condition (5) models an incompressible fluid. The divergence operators for tensor and vector-valued functions are defined by \(\mathop{\operatorname{Div}}\mathbb{S} = (\mathbb{S}_{ij,j})\) and \(\mathop{\operatorname{div}} \boldsymbol {u}= (u_{i,i})\), where the index that follows a comma represents the partial derivative with respect to the corresponding component of x. The homogeneous Dirichlet boundary condition (6) means that the fluid adheres to the wall, see, e.g., [7, 8, 14, 17, 27]. For convenience in notation, in boundary conditions (7)–(9), the traction vector is defined by

where the total stress is denoted by

and \(\mathbb{I}\) is the identity \(d\times d\) matrix. Hence

represent normal and tangential components of the traction vector, respectively. Note that τ and \(\tau _{\nu }\) do depend on the pressure p, and \(\boldsymbol {\tau }_{\tau }\) is independent of p.

The nonlinear boundary condition (7) describes a generalization, in several directions, of the Navier–Fujita slip condition. The following example of (7) has been studied by Le Roux and Tani in [14, 15]:

where \(\alpha \colon \Gamma _{1} \to (0,\infty )\) and \(\beta \colon \Gamma _{1} \times [0,\infty ) \to [0, \infty )\) are prescribed functions such that for a.e. \(\boldsymbol {x}\in \Gamma _{1}\), \(\beta (\boldsymbol {x}, r) = 0\) if and only if \(r = 0\), while \(\boldsymbol {w}_{\tau }\) denotes the tangential velocity of the wall surface at \(\Gamma _{1}\). Conditions (10) and (11) in the aforementioned papers are motivated by models of flows of polymer melts during extraction, flows of Newtonian fluids with a moving contact line, and flows of yield-stress fluids, etc. Condition (10) is called the impermeability (no leak) boundary condition, and (11) represents a nonlinear Navier–Fujita slip condition. Physically, condition (11) signifies that for the wall slip to occur the magnitude of the tangential traction has to exceed a prescribed “slip threshold”, denoted by α, independent of the normal stress, and if the slip occurs, the tangential traction equals to a given, nonlinear function of the slip velocity. Condition (11) has been considered as a generalization of three slip boundary conditions: the Navier slip condition in [23] (stating that the tangential velocity \(\boldsymbol {u}_{\tau }\) is proportional to the shear stress \(\boldsymbol {\sigma }_{\tau }\)), the nonlinear Navier-type slip condition in [14], and the threshold slip condition of “frictional type” studied in a series of papers by Fujita et al. [7–9, 25, 26]. Note that the nonlinear Navier–Fujita slip condition (11) is a particular case of condition (7) in Problem 3 with functions \(k(\boldsymbol {x}, \boldsymbol {\xi }) = \alpha (\boldsymbol {x}) + \beta (\boldsymbol {x}, \|\boldsymbol {\xi }\|_{ \mathbb{R}^{d}})\) and \(j(\boldsymbol {x}, \boldsymbol {\xi }) = \| \boldsymbol {\xi }\|_{\mathbb{R}^{d}}\) for a.e. \(\boldsymbol {x}\in \Gamma _{1}\), all \(\boldsymbol {\xi }\in \mathbb{R}^{d}\). The function j satisfies \(H(j)\) below with \(c_{0}(x) = 1\), \(c_{1} = 0\) since it is convex in the second variable. Further, condition (7) is much more general than (11) since it involves models with nonmonotone slip boundary condition of frictional type governed by nonconvex locally Lipschitz superpotentials j; for concrete examples, see [17, Example (60)] and the references therein.

Condition (8) has been recently suggested and studied in [31] to model a new outflow unilateral boundary condition for blood flow simulations. It has an advantage over the popular do-nothing boundary condition. In (8), g is a given positive constant and h is a prescribed nonnegative function. It is a counterpart of the Signorini-type condition which models the unilateral contact in the theory of elasticity [13, 28]. Moreover, condition (8) has been studied for the Stokes problem in [27] with \(h(\boldsymbol {x}; r) = h(\boldsymbol {x})\), and recently in [17]. The boundary condition (9) is called the generalized leak boundary condition of frictional type. It describes the lack of slip on the boundary \(\Gamma _{3}\) and a possible leakage of the fluid through this part of the boundary with a prescribed convex function ϕ. For the choice \(\phi (r) = |r|\) for \(r \in \mathbb{R}\) and further discussion, we refer to [17]. The generalized gradient for j and the convex subdifferential of ϕ are always taken with respect to the last variable of a given function.

In a particular case, Problem 3 has been studied in [10, 11] under the hypotheses \(\Gamma _{2} = \Gamma _{3} = \emptyset \) and the convex potential \(j(\boldsymbol {\xi }) = \| \boldsymbol {\xi }\|_{\mathbb{R}^{d}}\) for \(\boldsymbol {\xi }\in \mathbb{R}^{d}\). There, a weak form of Problem 3 was treated as a mixed variational formulation which couples a nonlinear variational inequality and an equation for the multiplier. This formulation is quite different to the one we study in the present paper. Due to the presence of both convex and nonconvex potentials, the weak formulation of Problem 3 leads to a variational–hemivariational inequality of elliptic type for the velocity field.

Next, we introduce the following spaces needed for the weak formulation.

The space V is endowed with the standard norm \(\| \boldsymbol {v}\| = \| \boldsymbol {v}\|_{H^{1}(\Omega; \mathbb{R}^{d})}\), and we also consider the norm given by \(\| \boldsymbol {v}\|_{V} = \| {\mathbb{D}} \boldsymbol {v}\|_{L^{2}(\Omega; \mathbb{M}^{d})}\) for \(\boldsymbol {v}\in V\). Using the Korn inequality

see [5, Theorem 8], it is known that \(\| \cdot \|_{H^{1}(\Omega; \mathbb{R}^{d})}\) and \(\| \cdot \|_{V}\) are the equivalent norms on V. The set of unilateral constraints for Problem 3 is given by

We recall that, for a bounded Lipschitz domain with boundary Γ, there exists a unique trace operator \(\gamma _{0} \colon H^{1}(\Omega; \mathbb{R}^{d}) \to H^{1/2}(\Gamma; \mathbb{R}^{d})\) which is linear, bounded, surjective, and such that \(\gamma _{0}(\boldsymbol {v}) = \boldsymbol {v}|_{\Gamma }\) for all \(\boldsymbol {v}\in C^{\infty }({\overline {\Omega }};\mathbb{R}^{d})\), see, e.g., [24, Chap. 2, Theorems 5.5 and 5.7]. There are various definitions of \(H^{1/2}(\Gamma; \mathbb{R}^{d})\) which are equivalent for Lipschitz boundaries, for details, see, e.g., [30, Chap. II.1.2, p. 47], [2, Chap. 3.2]. It follows from [16, p. 93] that the injection map \(i \colon H^{1/2}(\Gamma; \mathbb{R}^{d}) \to L^{2}(\Gamma; \mathbb{R}^{d})\) is compact. We use also the trace operator \(\gamma = i \circ \gamma _{0} \colon V \subset H^{1}(\Omega; \mathbb{R}^{d}) \to L^{2}(\Gamma; \mathbb{R}^{d})\) which is linear, bounded, compact, and its norm in the space \(\mathcal{L}(V,L^{2}(\Gamma; \mathbb{R}^{d}))\) is denoted by \(\|\gamma \|\). It is clear that the (tangential and normal) trace operator

is linear and bounded, where for a vector-valued function w on Γ, we denote by \(w_{\nu }\) and \(\boldsymbol {w}_{\tau }\) its normal and tangential components defined by \(w_{\nu }= \boldsymbol {w}\cdot \boldsymbol {\nu }\) and \(\boldsymbol {w}_{\tau }= \boldsymbol {w}- w_{\nu }\boldsymbol {\nu }\), respectively. Further, instead of γv, for simplicity, we retain the notation v.

We now introduce hypotheses on the dynamic viscosity μ, the nonconvex superpotential j, the convex potential ϕ, the functions h, k, and l, and the external body force density f in Problem 3.

\(\underline{H(\mu )}\): \(\mu \in L^{\infty }(\Omega )\) and \(0 < \mu _{0} \le \mu (\boldsymbol {x})\) for a.e. \(\boldsymbol {x}\in \Omega \).

\(\underline{H(h)}\): \(h \colon \Gamma _{2}\times \mathbb{R}\to \mathbb{R}\) is a function such that

-

(i)

\(h(\cdot,r)\) is measurable for all \(r\in \mathbb{R}\),

-

(ii)

\(h(\boldsymbol {x},\cdot )\) is continuous and nondecreasing for a.e. \(\boldsymbol {x}\in \Gamma _{2}\),

-

(iii)

\(0 \le h(\boldsymbol {x}, r) \le h_{0}\) for all \(r \in \mathbb{R}\) and a.e. \(\boldsymbol {x}\in \Gamma _{2}\),

-

(iv)

\(h(\boldsymbol {x}, 0) = 0\) for a.e. \(\boldsymbol {x}\in \Gamma _{2}\).

\(\underline{H(j)}\): \(j \colon \Gamma _{1}\times \mathbb{R}^{d} \to \mathbb{R}\) is a function such that

-

(i)

\(j(\cdot, \boldsymbol {\xi })\) is measurable on \(\Gamma _{1}\) for all \(\boldsymbol {\xi }\in \mathbb{R}^{d}\) and there is \(e \in L^{2}(\Gamma _{1}; \mathbb{R}^{d})\) such that \(j(\cdot, e(\cdot )) \in L^{1}(\Gamma _{1})\),

-

(ii)

\(j(\boldsymbol {x},\cdot )\) is locally Lipschitz for a.e. \(\boldsymbol {x}\in \Gamma _{1}\),

-

(iii)

\(\| \partial j(\boldsymbol {x},\boldsymbol {\xi }) \|_{\mathbb{R}^{d}} \le c_{0} (x) + c_{1} \| \boldsymbol {\xi }\|_{\mathbb{R}^{d}}\) for all \(\boldsymbol {\xi }\in \mathbb{R}^{d}\), a.e. \(\boldsymbol {x}\in \Gamma _{1}\) with \(c_{0} \in L^{2}(\Gamma _{1})\), \(c_{0}\), \(c_{1} \ge 0\),

-

(iv)

there exists \(\alpha _{j} \ge 0\) such that \(j^{0}(\boldsymbol {\xi }_{1}; \boldsymbol {\xi }_{2} - \boldsymbol {\xi }_{1}) + j^{0}(\boldsymbol {\xi }_{2}; \boldsymbol {\xi }_{1} - \boldsymbol {\xi }_{2}) \le \alpha _{j} \| \boldsymbol {\xi }_{1} - \boldsymbol {\xi }_{2} \|_{\mathbb{R}^{d}}^{2}\) for all \(\boldsymbol {\xi }_{1}\), \(\boldsymbol {\xi }_{2} \in \mathbb{R}^{d}\).

\(\underline{H(k)}\): \(k\colon \Gamma _{1} \times \mathbb{R}\to \mathbb{R}\) is a function such that

-

(i)

\(k(\cdot, r)\) is measurable on \(\Gamma _{1}\) for all \(r \in \mathbb{R}\),

-

(ii)

\(k(\boldsymbol {x}, \cdot )\) is continuous on \(\mathbb{R}\) for a.e. \(\boldsymbol {x}\in \Gamma _{1}\),

-

(iii)

\(0 < k_{0} \le k(\boldsymbol {x}, r) \le k_{1}\) for all \(r \in \mathbb{R}\), a.e. \(\boldsymbol {x}\in \Gamma _{1}\).

\(\underline{H(l)}\): \(l\colon \Gamma _{3} \times \mathbb{R}\to \mathbb{R}\) is a function such that

-

(i)

\(l(\cdot, r)\) is measurable on \(\Gamma _{3}\) for all \(r \in \mathbb{R}\),

-

(ii)

\(l(\boldsymbol {x}, \cdot )\) is continuous on \(\mathbb{R}\) for a.e. \(\boldsymbol {x}\in \Gamma _{3}\),

-

(iii)

\(0 < l_{0} \le l(\boldsymbol {x}, r) \le l_{1}\) for all \(r \in \mathbb{R}\), a.e. \(\boldsymbol {x}\in \Gamma _{1}\).

\(\underline{H(\phi )}\): \(\phi \colon \mathbb{R}\to \mathbb{R}\) is convex and lower semicontinuous.

\(\underline{H(f)}: \boldsymbol {f}\in V^{*}\).

\(\underline{(H_{0})}\): \(\alpha _{j} k_{1} \| \gamma \|^{2} < \mu _{0}\).

The condition \((H_{0})\) means that a “small” decrease (with respect to the lower bound \(\mu _{0}\) for the viscosity) of the graph of the subdifferential of j is permissible. As mentioned before, when \(j(\boldsymbol {x}, \cdot )\) is a convex potential, then \((H_{0})\) holds trivially with \(\alpha _{j} = 0\).

We now derive the variational formulation of Problem 3. We assume now that u and p are sufficiently smooth functions which satisfy (4)–(9). Let \(\boldsymbol {v}\in K\). We multiply equation (4) by \(\boldsymbol {v}- \boldsymbol {u}\) and integrate over Ω to find that

By using a second Green-type formula, see [20, Theorem 2.25], the fact that functions in V are divergence free, \(\boldsymbol {v}= \boldsymbol {u}= 0\) on \(\Gamma _{0}\) and \(v_{\nu }=u_{\nu }=0\) on \(\Gamma _{1}\), we obtain

By the Green formula in [20, Theorems 2.24], we get

Further, we employ the decomposition formula, see [20, relation (6.33)], condition \(\boldsymbol {u}= \boldsymbol {v}= 0\) on \(\Gamma _{0}\), and

to obtain

Now, taking into account the relations

we deduce

Therefore, combining (16), (17), and (18), we have

and finally

We utilize the subgradient boundary conditions (7) and (9) to obtain the following variational formulation of Problem 3.

Problem 4

Find a velocity \(\boldsymbol {u}\in K\) such that

Problem 4 is called a variational–hemivariational inequality on a convex set. The main existence result on Problem 4 is stated below, and its proof will be given in Sect. 4.

Theorem 5

Under hypotheses \(H(\mu )\), \(H(h)\), \(H(j)\), \(H(k)\), \(H(l)\), \(H(\phi )\), \(H(f)\), and \((H_{0})\), Problem 4has a solution.

4 Proof of Theorem 5

The proof is based on an application of Theorem 2 and a fixed point argument. We divide the proof into four steps.

Step 1. Let \(Y_{1} = H^{1/2}(\Gamma _{1};\mathbb{R}^{d})\) and \(Y_{2} = H^{1/2}(\Gamma _{3})\). Let \((\boldsymbol {\eta }, \xi ) \in Y_{1} \times Y_{2}\) be fixed. Consider the auxiliary problem

We shall prove that problem \(P(\eta, \xi )\) has a unique solution. With this problem, we associate the following inequality: find \(\boldsymbol {u}\in K\) such that

where \(A \colon V \to V^{*}\) and Φ, \(J \colon V \to \mathbb{R}\) are defined by

We shall verify conditions \(H(A)\), \(H(J)\), \(H(\Phi )\), \(H(K)\), \(H(f)\), and \((H_{0})\) of Theorem 2. The operator \(A_{1} \colon V \to V^{*}\) defined by

is linear, bounded, strongly monotone with constant \(m_{A} = \mu _{0} > 0\), and so also coercive. In particular, the function \(V \ni \boldsymbol {v}\mapsto \langle A_{1} \boldsymbol {v}, \boldsymbol {v}\rangle \in \mathbb{R}\) for \(\boldsymbol {v}\in V\) is strictly convex and lower semicontinuous, see, e.g., [28, Proposition 1.30]. Hence, it is weakly lower semicontinuous on V which implies

Next, we note that the nonlinear operator

is bounded, continuous (we use the compactness of the normal trace operator \(V \mapsto L^{2}(\Gamma _{2})\)), and monotone (by hypothesis \(H(h)\)(ii)). Further, by \(H(h)\)(ii) and the Hölder inequality, we get

In conclusion, the operator A given by (20) is bounded, continuous, and strongly monotone with constant \(m_{A} = \mu _{0}\), so by [20, Theorem 3.69], it is pseudomonotone. Condition \(H(A)\) is verified.

Hypothesis \(H(j)\)(i)–(ii) guarantees that the function J, given by (21), is well defined, and conditions \(H(J)\)(i) and (ii) follow from \(H(j)\)(i)–(iii), respectively, see [20, Theorem 3.47]. Condition \(H(J)\)(iii) is a consequence of the inequality

combined with hypothesis \(H(j)\)(iv). We obtain that \(H(J)\)(iii) holds with \(\alpha _{J} = \alpha _{j} k_{1} \| \gamma \|^{2}\).

Furthermore, taking into account hypothesis \(H(\phi )\), we deduce \(H(\Phi )\). The convexity of Φ is obvious. Let \(\{ \boldsymbol {v}^{n} \} \subset V\) be such that \(\boldsymbol {v}^{n} \to \boldsymbol {v}\) in V. We use the continuity of the normal trace operator \(V \ni \boldsymbol {v}\mapsto v_{\nu }\in L^{2}(\Gamma _{3})\) to get \(v^{n}_{\nu }\to v_{\nu }\) in \(L^{2}(\Gamma _{3})\), and next, at least for a subsequence, we have \(v^{n}_{\nu }(\boldsymbol {x}) \to v_{\nu }(\boldsymbol {x})\) for a.e. \(\boldsymbol {x}\in \Gamma _{3}\). From \(H(l)\)(iii) and \(H(\phi )\), we obtain

It is clear from [3, Proposition 5.2.25] that there are a, \(b \in \mathbb{R}\) such that \(\phi (r) \ge a r + b\) for all \(r \in \mathbb{R}\). Hence \(l(\xi (\boldsymbol {x})) \phi (v_{\nu }(\boldsymbol {x})) \ge \varrho _{1}(\boldsymbol {x})\) for a.e. \(\boldsymbol {x}\in \Gamma _{3}\) and all \(\boldsymbol {v}\in V\) with \(\varrho _{1}(\boldsymbol {x}):= -l_{1} (|a| |v_{\nu }(\boldsymbol {x})| + |b|)\) a.e. \(\boldsymbol {x}\in \Gamma _{3}\). By a direct calculation, we get \(\int _{\Gamma _{3}} \varrho _{1} \,d\Gamma \ge - m_{1} \| \boldsymbol {v}\|_{V} - m_{2}\) for \(\boldsymbol {v}\in V\) with \(m_{1}\), \(m_{2} \ge 0\). Therefore \(\varrho _{1} \in L^{1}(\Gamma _{3})\). Using the latter and integrating both sides of (26), by Fatou’s lemma, it yields

which shows that Φ is a lower semicontinuous function on V. Thus, \(H(\Phi )\) is proved.

Subsequently, it is easy to see that the set of unilateral constraints (14) is closed and convex in V with \(\boldsymbol {0}\in K\) and, thus, condition \(H(K)\) is satisfied. Finally, the hypothesis \((H_{0})\) assures that the smallness condition (1) holds. Having verified the hypotheses of Theorem 2, we deduce that there exists a unique solution \(\boldsymbol {u}= \boldsymbol {u}_{\xi \eta } \in K\) to problem (19). Using inequality (25), we know that \(\boldsymbol {u}= \boldsymbol {u}_{\xi \eta } \in K\) is also the solution to problem \(P(\eta, \xi )\).

By the direct computation, we can show that the solution to problem \(P(\eta, \xi )\) is unique. Indeed, let \(\boldsymbol {u}_{1}\), \(\boldsymbol {u}_{2} \in V\) be solutions to problem \(P(\eta, \xi )\). Choosing the test function \(\boldsymbol {v}= \boldsymbol {u}_{2} \in K\) in the inequality satisfied by \(\boldsymbol {u}_{1}\), and \(\boldsymbol {v}= \boldsymbol {u}_{1} \in K\) in the inequality satisfied by \(\boldsymbol {u}_{2}\), and then adding the two resulting inequalities, we obtain

Taking into account the strong monotonicity of the operator A and hypotheses \(H(j)\)(iv), \(H(k)\)(iii) as well as the continuity of the trace operator γ, we have

Finally, due to hypothesis \((H_{0})\), we deduce \(\boldsymbol {u}_{1} = \boldsymbol {u}_{2}\). In conclusion, problem \(P(\eta, \xi )\) has a unique solution.

Step 2. We shall show the estimate on the unique solution \(\boldsymbol {u}= \boldsymbol {u}_{\xi \eta } \in K\) to \(P(\eta, \xi )\). We choose \(\boldsymbol {v}= \boldsymbol {0}\in K\) in the inequality \(P(\eta, \xi )\) to get

From (2), \(H(l)\), and \(H(\phi )\), it is clear that

By [3, Proposition 5.2.25], it follows that Φ is bounded from below by an affine function, i.e., there are \(q \in V^{*}\) and \(\beta \in \mathbb{R}\) such that \(\Phi (\boldsymbol {v}) \ge \langle q, \boldsymbol {v}\rangle + \beta \) for all \(\boldsymbol {v}\in V\). Hence

Subsequently, from \(H(j)\)(iii), (iv) and the inequality \(\| \boldsymbol {u}_{\tau }\|_{\mathbb{R}^{d}} \le \| \boldsymbol {u}\|_{\mathbb{R}^{d}}\), we deduce

Due to \(H(k)\), the continuity of the trace operator \(V \mapsto L^{2}(\Gamma _{1}; \mathbb{R}^{d})\), and the Hölder inequality, we have

Combining (28)–(30) with (27), we obtain

We use the relation

to conclude that

where the constant \(M > 0\) is such that

Step 3. Let \(\Lambda \colon Y_{1} \times Y_{2} \to Y_{1} \times Y_{2}\) be defined by

where \(\boldsymbol {u}= \boldsymbol {u}_{\eta \xi } \in K\) is the unique solution to problem \(P(\eta, \xi )\). Note that Λ is well defined, and by (32), the continuity of the trace operator (15), and the elementary inequalities \(\| \boldsymbol {u}_{\tau }\|_{\mathbb{R}^{d}} \le \| \boldsymbol {u}\|_{\mathbb{R}^{d}}\) and \(u_{\nu }\le |u_{\nu }| \le \| \boldsymbol {u}\|_{\mathbb{R}^{d}}\), we have

In other words, due to the uniform bounds for k and l, the image of the whole space \(Y_{1} \times Y_{2}\) remains in a closed ball in \(Y_{1} \times Y_{2}\), that is,

Next, we shall show that Λ is a weakly-weakly continuous map. Let \((\boldsymbol {\eta }_{n}, \xi _{n})\), \((\boldsymbol {\eta },\xi ) \in Y_{1} \times Y_{2}\) such that

Using the compactness of the embedding \(H^{1/2}(\Gamma; \mathbb{R}^{d})\) into \(L^{2}(\Gamma; \mathbb{R}^{d})\), (35) implies

and therefore we can assume that

Let \(\boldsymbol {u}^{n}_{\eta _{n} \xi _{n}} \in K\), \(n \in \mathbb{N}\), be the unique solution to problem \(P(\eta _{n}, \xi _{n})\) corresponding to \((\boldsymbol {\eta }_{n}, \xi _{n})\). For simplicity, we write \(\boldsymbol {u}^{n} = \boldsymbol {u}^{n}_{\eta _{n} \xi _{n}}\) and we have

where A is the operator defined by (20). By estimate (32) in Step 2, we know that \(\{ \boldsymbol {u}^{n} \}\) remains uniformly bounded in V. Thus, by the reflexivity of V, there is a subsequence of \(\{ \boldsymbol {u}^{n} \}\), denoted in the same way, and \(\boldsymbol {u}\in V\) such that

Since \(\{ \boldsymbol {u}^{n} \} \subset K\) and K is weakly closed in V (being closed and convex), we have \(\boldsymbol {u}\in K\). From the compactness of the trace operator γ and the converse Lebesgue dominated convergence theorem [20, Theorem 2.39], we may suppose that \(\boldsymbol {u}^{n} \to \boldsymbol {u}\) in \(L^{2}(\Gamma; \mathbb{R}^{d})\) and

with \(\rho \in L^{2}(\Gamma )\). Next, let \(\boldsymbol {v}\in K\). We use \(H(j)\)(iii), \(H(k)\)(iii), and [20, Proposition 3.23 (iii)] to obtain

where \(\varrho \in L^{1}(\Gamma _{1})\). In view of the latter, by Fatou’s lemma, we have

On the other hand, we employ (40), the upper semicontinuity of the function \(j^{0}(\cdot; \cdot )\), see [20, Proposition 3.23(ii)], and get

Combining (35), (41), and (42), it follows

for all \(\boldsymbol {v}\in V\). In a similar way to (43), we can use (35), \(H(l)\), \(H(\phi )\), and Fatou’s lemma to obtain

for all \(\boldsymbol {v}\in V\).

We are now in a position to pass to the limit in (38), as \(n \to \infty \). To this end, we use convergences (23), (24), (39), (43), and (44) to deduce

for all \(\boldsymbol {v}\in K\). This means that \(\boldsymbol {u}\in K\) is the solution to problem \(P(\eta, \xi )\) corresponding to \((\eta, \xi )\). Since the problem admits a unique solution, the whole sequence \(\{ \boldsymbol {u}^{n} \}\) converges weakly in V to u. Since the (tangential and normal) trace operator (15) is linear and continuous, we have

and \(\Lambda (\boldsymbol {\eta }_{n}, \xi _{n}) \rightharpoonup \Lambda (\boldsymbol {\eta }, \xi )\) in \(Y_{1} \times Y_{2}\). This proves the weak-to-weak continuity of the map Λ.

Step 4. We apply the Schauder fixed point theorem in its weak variant, see, e.g., [12, p. 185].

Theorem 6

Let X be a separable reflexive Banach space and \(C \subset X\) be nonempty, convex, and weakly compact in X. Let \(S \colon C \to C\) be weak-to-weak continuous. Then S has a fixed point.

From Step 2, we know that the map Λ is continuous in the weak topology and it satisfies (34). By the reflexivity of \(Y_{1} \times Y_{2}\), it is clear that the closed ball is weakly compact and obviously convex. Thus Λ has a fixed point \((\boldsymbol {\eta }^{*}, \xi ^{*}) \in Y_{1} \times Y_{2}\), that is,

where \(\boldsymbol {u}_{\eta ^{*}\xi ^{*}} \in K\) solves problem \(P(\eta ^{*}, \xi ^{*})\). We conclude that \(\boldsymbol {u}_{\eta ^{*}\xi ^{*}}\in K\) is a solution to Problem 4. The proof is complete. □

5 Compactness and uniqueness results

We conclude the paper with the following compactness and uniqueness results for Problem 4.

Theorem 7

Under the hypotheses of Theorem 5, the set of solutions to Problem 4is weakly compact in V.

Proof

Let S be the solution set to Problem 4. It is a nonempty subset of V by Theorem 5. Let \(\{ \boldsymbol {u}^{n} \} \subset S\), so \(\boldsymbol {u}^{n} \in K\) and

Next, we follow the arguments used in Steps 2 and 3 of Theorem 5 to demonstrate that \(\{ \boldsymbol {u}^{n} \}\) is uniformly bounded in V and, at least for a subsequence, \(\boldsymbol {u}^{n} \to \boldsymbol {u}^{0}\) weakly in V, where \(\boldsymbol {u}^{0} \in K\) solves Problem 4. Hence \(\boldsymbol {u}^{0} \in S\). This completes the proof. □

The uniqueness of a solution to Problem 4 under the general hypotheses of Theorem 5 is an open problem. However, it can be obtained, for instance, under the additional assumptions stated below.

Theorem 8

Assume the hypotheses of Theorem 5and the following conditions:

Then Problem 4has a unique solution.

Proof

Let \(\boldsymbol {u}_{1}\), \(\boldsymbol {u}_{2} \in K\) be solutions to Problem 4. We take the test function \(\boldsymbol {v}= \boldsymbol {u}_{2}\) in the inequality satisfied by \(\boldsymbol {u}_{1}\), and \(\boldsymbol {v}= \boldsymbol {u}_{1}\) in the inequality satisfied by \(\boldsymbol {u}_{2}\). Next, we add the resulting inequalities to get

where the operator A is defined by (20). Hence, we have

with

Note that \(j(\boldsymbol {x}, \cdot )\) is Lipschitz with constant \(L_{j} > 0\) for a.e. \(\boldsymbol {x}\in \Gamma _{1}\) if and only if \(\|\partial j(\boldsymbol {\xi })\|_{\mathbb{R}^{d}} \le L_{j}\) for all \(\boldsymbol {\xi }\in \mathbb{R}^{d}\). Under the hypotheses, we use the continuity of the trace operator γ, and by a direct calculation, we deduce

Combining these inequalities with (46) and the strong monotonicity of the operator A imply

Finally, from (45), we deduce \(\boldsymbol {u}_{1} = \boldsymbol {u}_{2}\). The proof is complete. □

Example 9

We provide examples of functions j and ϕ. Let \(j \colon \mathbb{R}^{d} \to \mathbb{R}\) be defined by

with a constant \(a \in [0, 1)\). Then the generalized gradient has the form

The function j is nonconvex and \(\|\partial j(\boldsymbol {\xi })\|_{\mathbb{R}^{d}} \le 1\) for all \(\boldsymbol {\xi }\in \mathbb{R}^{d}\). Further, it satisfies \(H(j)\) with \(c_{0} = 1\), \(c_{1} = 0\) and \(\alpha _{j} = 1\), and j is Lipschitz continuous with \(L_{j} = 1\). Let \(\phi \colon \mathbb{R}\to \mathbb{R}\) be defined by

Then the function ϕ is convex, continuous, and

So it satisfies \(H(\phi )\), \(|\partial \phi (r)| \le 2\) for all \(r \in \mathbb{R}\), and it is Lipschitz with \(L_{\phi }= 2\).

Finally, we observe that any smooth solution to Problem 4 is a solution to Problem 3. In fact, we are able to recover the pressure from the weak formulation. For the proof, see [17, Proposition 17].

Proposition 10

If \(\boldsymbol {u}\in K\) is a solution to Problem 4given by Theorem 5which is smooth \(\boldsymbol {u}\in H^{2}(\Omega; \mathbb{R}^{d})\), then u satisfies the conditions of Problem 3. In particular, there exists a unique \(p \in L^{2}(\Omega )\) such that \(\int _{\Omega }p \,dx = 0\) which satisfies (4)–(9).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Clarke, F.H.: Optimization and Nonsmooth Analysis. Wiley, New York (1983)

Demengel, F., Demengel, G.: Functional Spaces for the Theory of Elliptic Partial Differential Equations. Springer, London (2012)

Denkowski, Z., Migórski, S., Papageorgiou, N.S.: An Introduction to Nonlinear Analysis: Theory. Kluwer Academic, Dordrecht (2003)

Denkowski, Z., Migórski, S., Papageorgiou, N.S.: An Introduction to Nonlinear Analysis: Applications. Kluwer Academic, Dordrecht (2003)

Dudek, S., Kalita, P., Migórski, S.: Stationary flow of non-Newtonian fluid with frictional boundary conditions. Z. Angew. Math. Phys. 66, 2625–2646 (2015)

Dudek, S., Migórski, S.: Evolutionary Oseen model for generalized Newtonian fluid with multivalued nonmonotone friction law. J. Math. Fluid Mech. 20, 1317–1333 (2018)

Fujita, H.: A mathematical analysis of motions of viscous incompressible fluid under leak or slip boundary conditions. RIMS Kokyuroku 888, 199–216 (1994)

Fujita, H.: Non stationary Stokes flows under leak boundary conditions of friction type. J. Comput. Math. 19, 1–8 (2001)

Fujita, H.: A coherent analysis of Stokes flows under boundary conditions of friction type. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 149, 57–69 (2002)

Haslinger, J., Kučera, R., Šátek, V., Sassi, T.: Stokes system with solution-dependent threshold slip boundary conditions: analysis, approximation and implementation. Math. Mech. Solids 23, 294–307 (2018)

Haslinger, J., Stebel, J.: Stokes problem with a solution dependent slip bound: stability of solutions with respect to domains. Z. Angew. Math. Mech. 96, 1049–1060 (2016)

Hlaváček, I., Haslinger, J., Nečas, J., Lovíšek, J.: Solution of Variational Inequalities in Mechanics. Applied Mathematical Sciences, vol. 66. Springer, Berlin (1988)

Kikuchi, N., Oden, J.T.: Contact Problems in Elasticity: A Study of Variational Inequalities and Finite Element Methods. SIAM, Philadelphia (1988)

Le Roux, C.: Existence and uniqueness of the flow of second-grade fluids with slip boundary conditions. Arch. Ration. Mech. Anal. 148, 309–356 (1999)

Le Roux, C., Tani, A.: Steady solutions of the Navier–Stokes equations with threshold slip boundary conditions. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 30, 595–624 (2007)

Lions, J.-L.: Optimal Control of Systems Governed by Partial Differential Equations. Springer, Berlin (1971)

Migórski, S., Dudek, S.: A new class of variational-hemivariational inequalities for steady Oseen flow with unilateral and frictional type boundary conditions. Z. Angew. Math. Mech. 100, e201900112 (2020)

Migórski, S., Ochal, A.: Hemivariational inequalities for stationary Navier–Stokes equations. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 306, 197–217 (2005)

Migórski, S., Ochal, A.: Navier–Stokes problems modelled by evolution hemivariational inequalities. Discrete Contin. Dyn. Syst. 2007, 731–740 (2007)

Migórski, S., Ochal, A., Sofonea, M.: Nonlinear Inclusions and Hemivariational Inequalities. Models and Analysis of Contact Problems. Advances in Mechanics and Mathematics, vol. 26. Springer, New York (2013)

Migórski, S., Ochal, A., Sofonea, M.: A class of variational-hemivariational inequalities in reflexive Banach spaces. J. Elast. 127, 151–178 (2017)

Migórski, S., Paczka, D.: On steady flow of non-Newtonian fluids with frictional boundary conditions in reflexive Orlicz spaces. Nonlinear Anal., Real World Appl. 39, 337–361 (2018)

Navier, C.L.M.H.: Memoire sur les lois du mouvement des fluides. Mem. Acad. R. Sci. Inst. A. 6, 389–440 (1823)

Nečas, J.: Direct Methods in the Theory of Elliptic Equations. Springer, Berlin (2012)

Saito, N.: On the Stokes equations with the leak and slip boundary conditions of friction type: regularity of solutions. Pub. RIMS, Kyoto University 40, 345–383 (2004)

Saito, N., Fujita, H.: Regularity of solutions to the Stokes equation under a certain nonlinear boundary condition. Lect. Notes Pure Appl. Math. 223, 73–86 (2001)

Saito, N., Sugitani, Y., Zhou, G.: Unilateral problem for the Stokes equations: the well-posedness and finite element approximation. Appl. Numer. Math. 105, 124–147 (2016)

Sofonea, M., Matei, A.: Mathematical Models in Contact Mechanics. London Mathematical Society Lecture Note, vol. 398. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2012)

Sofonea, M., Migórski, S.: Variational-Hemivariational Inequalities with Applications. Monographs and Research Notes in Mathematics. Chapman & Hall/CRC, Boca Raton (2018)

Sohr, H.: The Navier–Stokes Equations, an Elementary Functional Analytic Approach. Springer, Basel (2001)

Zhou, G., Saito, N.: The Navier–Stokes equations under a unilateral boundary condition of Signorini’s type. J. Math. Fluid Mech. 18, 481–510 (2016)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the funding institutions for their support.

Funding

The work is supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 823731 CONMECH, Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi Grant Nos: 2018GXNSFAA281353 and 2020GXNSFAA159052, and by the Beibu Gulf University under project No. 2018KYQD06. The second author is also supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher E ducation of Republic of Poland under Grants Nos. 4004/GGPJII/H2020/2018/0 and 440328/PnH2/2019.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SM developed the mathematical methods. SD discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript. JZ contributed to typing and corrections. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, J., Migórski, S. & Dudek, S. Analysis of Stokes system with solution-dependent subdifferential boundary conditions. Fixed Point Theory Algorithms Sci Eng 2021, 19 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13663-021-00704-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13663-021-00704-5